Abstract

Introduction

Regular screening facilitates early diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) and reduction of CRC morbidity and mortality. Screening rates for minorities and low-income populations remain suboptimal. Provider referral for CRC screening is one of the strongest predictors of adherence, but referrals are unlikely among those who have no clinic home (common among poor and minority populations).

Methods/study design

This group randomized controlled study will test the effectiveness of an evidence based tailored messaging intervention in a community-to-clinic navigation context compared to no navigation. Multicultural, underinsured individuals from community sites will be randomized (by site) to receive CRC screening education only, or education plus navigation. In Phase I, those randomized to education plus navigation will be guided to make a clinic appointment to receive a provider referral for CRC screening. Patients attending clinic appointments will continue to receive navigation until screened (Phase II) regardless of initial arm assignment. We hypothesize that those receiving education plus navigation will be more likely to attend clinic appointments (H1) and show higher rates of screening (H2) compared to those receiving education only. Phase I group assignment will be used as a control variable in analysis of screening follow-through in Phase II. Costs per screening achieved will be evaluated for each condition and the RE-AIM framework will be used to examine dissemination results.

Conclusion

The novelty of our study design is the translational dissemination model that will allow us to assess the real-world application of an efficacious intervention previously tested in a randomized controlled trial.

1. Introduction

Regular screening facilitates the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC), the second leading cause of cancer death, and contributes to the reduction of CRC morbidity and mortality [1]. <40% of CRC cases are diagnosed early; clearly, life-saving screening rates have not kept pace with increasing incidence and prevalence.

A recent trend is an increase in CRC screening test utilization (from 38% in 2000 to 65.4% screened according to guidelines in 2010) [2,3], (falling far short of the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable, goal of 80% by 2018 [4], and that trend is not mirrored in poor and minority populations, highlighting the need to implement effective interventions targeting the underserved. For most Americans, a primary care facility is the main point of entry into the health care system [5]. Interventions tested in these settings with providers, systems, or patients have generally produced increases in screening [6–11], especially when patient navigators are used after the point of screening referral [7,12,13], but the hardest-to-reach patients are still overlooked. A large proportion of ethnically diverse, poor, and underserved patients do not regularly visit such clinics [14]. CRC screening rates are particularly low for those who do not have a primary care provider or clinic and who also have lower levels of education, income, and insurance [2,15], underscoring the need to identify patients in community settings to facilitate entry into the primary care system for requisite referrals for CRC screening.

Even in the context of primary care system contact, there continue to be a number of barriers to CRC screening, including insurance and cost issues [16,17]; transportation and other logistical (family, time off work) challenges [18–22]; ineffective doctor-patient communication [23]; lack of knowledge, misconceptions, and fear [17,22–27]. Absence of symptoms have been shown to be significant reasons for non-adherence with both stool blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy [21,28, 29–32]. Most importantly, health care provider failure to recommend CRC screening or not having a usual source of care also hinders early detection and prevention efforts [21,25,30,33–37]. These factors indicate that education (on critical CRC risk, benefits, options, and ways to overcome barriers) and receiving a physician referral are necessary but often not sufficient requirements to move individuals to obtain CRC screening.

This study incorporated primary elements of two interventions tested by the co-PIs, Drs. Menon and Larkey: a) a tailored CRC screening education intervention in primary care clinics that directly addresses individual barriers to taking the steps to obtain screening through scripted, “tailored messaging” responses [2.2 odds of being screened for CRC compared to usual care [13]] and b) a matched control, pilot study with un- or underinsured, low-income participants, all receiving an initial community class on the importance and procedures in CRC screening, showing higher rates of screening among those receiving education plus navigation (i.e., guided via phone calls, using tailored responses to barriers) from the community setting into clinics (35% completing screening) compared to those receiving only education (without navigation) (11.8% completing screening) [38]. Given the prior success of the scripted, tailored education intervention, delivered telephonically, [13] and the pilot study examining a context for reaching individuals in underserved community settings to navigate to clinics, [38] the currently described research is designed to test these combined elements in a dissemination study.

The study is funded by the National Cancer Institute, (Grant Number: 1 R01 CA162393-01A1), and the proposed study design was written in response to PAR 10-038, Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (R01). “Dissemination” in this PAR is described as “the targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience”. The intent is to spread knowledge and the associated evidence-based interventions”. In our study, the navigation messaging is based on an evidence-based tailored messaging intervention (scripted materials and strategy) to be tested in the community-to-clinic navigation context in order to disseminate to a different context. Getting community participants who are not necessarily tied to a medical home to go into a clinic to receive a CRC referral is a critical first step in the process (especially considering the very low rates of screening—11.8%, when only community education without navigation to a clinic was provided in our pilot study). For this reason, the first milestone for assessment in response to the navigation was attendance at a clinic appointment.

2. Methods

The purpose of this study is to extend the pilot study in a group-ran-domized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of tailored messaging delivered by Community Health Navigators (CHNs) to guide individuals from especially hard-to-reach, multicultural, and underinsured communities into primary care clinics for referral for CRC screening (Phase I) and to continue navigation after referral to track effects of the intervention on completion of CRC screening (Phase II). The initial intervention for all participants includes a group education class on the importance of CRC prevention and screening followed by the tailored navigation intervention vs the no-navigation control condition. Costs of the navigation intervention compared to the no-navigation condition will be tracked throughout the study to support a cost-effectiveness analysis. Additionally, description of dissemination efforts and outcomes will be tracked and reported using the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) [66] framework.

A Cultural Community Advisory Board (with members from an already existing board and new members) and investigators/consultants, specifically representing those cultures represented in our selected low-income communities (Latino, African American, American Indian and Asian American), will address a range of cultural alignment issues in our study region, Maricopa county, Arizona.

Hypothesis 1

Individuals receiving group education classes + tailored navigation will show higher rates of clinic attendance than those receiving only group education.

Hypothesis 2

Individuals receiving group classes and tailored navigation during Phase I will have higher rates of CRC screening test completion than those receiving classes only, (however this outcome will be primarily due to clinic attendance).

Cost effectiveness aim: Determine the cost-effectiveness of group education plus tailored navigation in increasing clinic appointments and CRC screening completion among low-income, multicultural Arizo-na residents aged 50 or older.

Dissemination aim: Examine the levels of program dissemination from community to clinic to final screening uptake using the RE-AIM model, asking, “What is the degree of Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of the community-to-clinic navigation, and clinic-to-screening outcomes?”

2.1. Study design overview

This 2-phase experimental, randomized design will test the dissemination of a community-to- clinic tailored navigation intervention: to increase attendance at primary care clinics (Phase I), to track CRC screening among those who visit clinics (Phase II), evaluate cost effectiveness and dissemination via the RE-AIM model.

In Phase I, community sites will be randomized to either group education (GE) or group education plus tailored navigation (GE + TN) to increase attendance at the primary care clinics. In Phase II, individuals who complete a clinic appointment (from Phase I) will then receive the standard of care (provider prompts, navigation calls to patients) in the clinic. Phase I brings individuals into the primary care system (clinic attendance), and Phase II follows them through to CRC screening completion (either stool-based or colonoscopy). An accelerated plan will be initiated for individuals identified as at high risk for CRC, referring them for colonoscopy, to realistically evaluate effects of the interventions in real-world conditions, including the range of patient risk pro-files in this setting.

2.2. Study population and setting

Inclusion criteria: participants aged 50–75, speak either English or Spanish, live in low-income neighborhoods (including a range of race and ethnicities), are due for CRC screening, and may be at average or high risk for CRC. Most community-based studies focus only on average-risk individuals. In Maricopa county, the research team’s prior CRC screening related projects accessed zip-code areas that include a large proportion of Latinos (86.9% with no stool test in the past 2 years), or poor (76.4% unscreened with household incomes less than $15,000, and 83.9% with incomes $15,000–24,999) and one zip code area with higher proportions of American Indian (AI) near two clinics that serve this population [39,40]. Recruitment in these same zip codes are expected to reach a substantial proportion of underserved and under-screened individuals. Appropriately, safety-net clinics, including Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and FQHC look-alikes that primarily serve low-income populations are located in these areas, so that the catchment areas of our study will include networks of community-based organizations (and other types of sites) where these populations may be engaged. Our study team currently has commitments from one standalone free clinic, a clinic serving Native Americans via Indian Health Services and other funding (an FQHC blend), and a large county clinic system with several FHQCs to receive study participants.

A Cultural Community Advisory Board will advise the study team and provide referrals to sites that represent our intended recruitment population. The Board is comprised of community leaders representing African American, Latino, American Indian and Asian American community groups. Specific components they will assist with are adapting the consent form, data collection methods, and intervention materials for cultural fit across our multicultural population of low-income participants (as well as language fit for our predominant Latino population, with translation of materials and bilingual staff for Spanish speakers). The inclusion of monolingual Spanish-speaking individuals is imperative in our region because Latinos comprise 31% of the Maricopa County population, and even though a large proportion speak English, those who are Latino, of lower income, and lower acculturated status are less likely to be screened [4]. Our recruitment goals, by ethnic and racial categories, parallel or exceed the population proportions (e.g., 4.3% Afri-can American, 3% Asian, 1.7% Native American,). Very small proportions of the Asian and Native American populations in our study region do not speak English and are therefore not included in the study.

2.3. Recruitment

Sites will be identified for recruitment (with the goal of reaching low income participants primarily from neighborhoods of higher proportions of underserved racial and ethnic minorities with lower rates of CRC screening) by (a) visiting previously engaged and new institutional sites (churches, senior citizen centers, employers) [41], (b) continuing to canvass nontraditional options (apartment complexes, neighborhood associations, barber shops/salons, areas of commerce, bowling alleys, food banks), and (c) investigating new types of sites to reach a broader range of multicultural populations in low-income areas in the targeted county. Members of our Cultural Community Advisory Board include both lay advisors and strong community leaders and directors representing key institutions with community links and they will continue to advise on places to go to reach our population of interest. Efforts to recruit sites with participants from underserved populations with low CRC screening rates will be made through accessing community contacts from previous work by the study team in the region.

Once identified, sites will be approached to gain permission to access people who visit these sites, where appropriate (e.g., churches, senior centers, bowling alleys), or to scope out and describe the population that naturally occurs in a non-institutional site (e.g., food truck gatherings) where permission is not relevant. Information on age, ethnicity, and insurance status will be assessed (and used in randomization procedures, see below). Once sites are randomized, participants will be recruited through individual and/or group contact. Our staff will visit community sites to informally visits with members in attendance, as well as, when the site is amenable, schedule and promote presentations providing information to potential participants on study goals and intervention information. Eligibility screening and consent will be administered one-on-one by study staff (in English or Spanish) at the site recruitment events or scheduled at a later time. Baseline questionnaires will be administered after presentations, eligibility screening and consent or scheduled later at the site or by calling the individual at home, prior to the intervention (GE or GE + TN),. Once consented, a participant will be scheduled to attend a class held at the site at which they were recruited. Follow up phone calls will be made to remind participants to attend class.

2.4. Randomization: Phase I

We expect to engage in approximately 133 control group sites and 133 intervention group sites to participate in the study, to be random-ized to GE classes with TN or to GE alone in Phase I. In the most recent review of screening rates in the US, disparities were strongest (lowest screening prevalence) for persons aged 50–59 years (53.9%), Hispanics (49.8%), persons with lower income (47.6%), those with less than a high school education (46.1%) [2]. Our project sites will predominantly be low-income, lower level education, and so the first two factors (age and ethnicity) have been chosen as likely factors to influence screening behavior and therefore used as matching criteria for balanced study arm assignment. Once 6–8 sites are identified and our site coordinators have helped us to estimate these factors, as well as site type and size, this information (age and ethnicity) will be provided to the study statistician to randomly assign the groups using the minimization method of assignment (Minimizaton-8 software) [42]. This method reduces the amount of systematic selection bias by controlling for potentially confounding covariates; in this case, age and ethnicity. Study staff who call participants to verify screening status through Phase II will be blinded to study assignment.

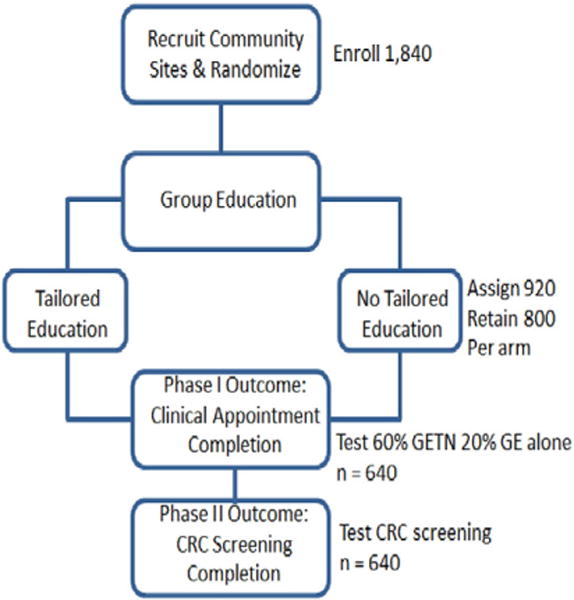

We expect to recruit and randomize 1840 participants total, allowing 15% attrition (that is, 85% retention) to have 1600 participants, which will form into approximately 266 groups of 5–7 participants, resulting. Approximately 450 participants will be recruited each year to achieve total recruitment goals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant flow, sample size, and hypothesis testing.

Education group classes will begin in staggered sessions over 46 months, marking the start of each group’s starting time and then commencing the tailored navigation or no-navigation intervention period will be initiated for 20 weeks from that start of each class.

2.5. Power analysis and sample size

We calculated the necessary sample size for our Phase I outcome, clinic appointment completion, based on our experience with pilot studies. We powered our analyses to test whether only 20% of the GE alone and 60% of the GE + TN were to complete their clinic appointment (expecting that this smaller proportion of participants in the no-navigation condition would proceed to make and keep a clinic appointment, while much larger proportion of participants receiving TN would proceed as such). With these proportions, we would require 1600 participants. Factoring in an 85% sample retention for Phase I, it was determined that 1840 participants would have to be recruited (1:1 allocation, 920 per arm) to assure that 640 (total from both groups) complete their clinic appointments. This sample size will provide an 87% ability to detect the difference between 20% GE alone and 60% GE + TN in appointment completion, using a two-tailed chi-square test with critical level = 0.05. We calculated the necessary sample size for our Phase II outcome, CRC screening completion, using an odds ratio of 2.2 [43] for the GE + TN group versus GE alone, taking into account initial group assignment. As the number of community sites (clusters) is expected to be N200 and the number of persons per site anticipated to be no N10, a conservative ICC of 0.15 was used in calculations. Using power computations by Hedeker, et al. [44] for two-group comparisons on dichotomous outcomes in a multi-level framework, it was determined that 640 would provide an 80% ability to detect a 50% difference in CRC screening completion.

3. Interventions

3.1. Group education for both arms of the study (Phase I)

Groups of participants will be assembled for education sessions after all baseline surveys are completed for a site. The curriculum for the 50-min session will include general information on cancer risk, specific risk factors for CRC, and brief review of dietary and physical activity changes. At least 25 min of the class time will be devoted to describing the purpose, preparation, and procedures for blood stool testing, reasons for annual testing, meaning of results, and importance of follow-up for positive tests. The first line of defense selected for this study is stool blood testing, as this fits with the preferences of our lower-income populations, more likely to gain compliance, and three of our committed clinic partners serving our population have agreed to promote the highest quality stool-based tests. These are the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) and the guaiac-based Hemoccult Sensa and Hemoccult II [45–47], showing much better sensitivity for cancer (with even sensitivity N50% for advanced adenomas for FIT) than earlier FOBT technology upon which much of the early mortality-reduction evidence was based. Colonoscopy will be promoted only for those at high-risk (explained in more detail below). Kits will be provided for mock demonstration and discussion. Another 10 min will be used to discuss colonoscopy, preventative potential when polyps are removed, and what is involved in preparation, anesthesia, and need for a driver to take one home after the procedure. Clear guidelines regarding use of colonoscopy as the primary screening tool for individuals at higher risk, and for those who test positive on stool-based screening will be discussed. A multicultural, culturally sensitive team of Community Health Navigators (CHNs) with prior experience in teaching cancer prevention and screening behaviors in multicultural contexts will contribute to the development of a manual and will use this manual as they learn to teach the class, teaching the class to each other and to members of the Cultural Community Advisory Board for practice and feedback. Standardization and fidelity [48] will be maintained by using checklists of the topics and activities covered to track completion.

3.2. Tailored navigation (TN) Phase I

Participants randomized to the groups receiving GE + TN intervention will be called within 5 days of the completion of the class and will be encouraged to schedule an appointment at the nearby identified clinic. The CHNs (including 2 bilingual English/Spanish speakers, one Afri-can American and one Native American) will be selected based on prior community experience with their respective racial/ethnic communities and paid as community health educators by the study funding. They will navigate participants through their individual barriers and concerns, using the tailored set of responses from a message library which was developed in the co-PI’s previous research [43,49]. A subset of these messages were selected and pilot-tested/adapted for the specific community context (e.g., overcoming fear/anxiety or clearing up misconceptions about screening, taking the first step to make an appointment, planning transportation to the clinic) and local population in Arizona in the investigators– navigation pilot study. Calls will continue, for a total of 5 (including the first call within 5 days of the class) within a 10-week period (or less, if attendance to clinic and/or adherence to screening are completed). Every call will track the barriers noted and TN response, up to the point of making the appointment.

3.3. Control conditions (group education only, no navigation)

In Phase I, participants in the control arm of the study will receive only 3 calls from staff not conducting navigation. These calls are designed to support data collection and tracking, but participants will not be asked about their barriers and will not receive tailored navigation messages. Call 1 will be made 1–2 weeks after the education intervention to verify contact information and to inquire whether an appointment was made. Call 2 will be made during weeks 5–6 to inquire if a clinic appointment was made and kept and to schedule a final call for week 8–10. Call 3 will also be used to inquire if a clinic appointment was made and kept, and if not, no further calls will be made. If an appointment was made and kept, the participant will be followed through Phase II. If an appointment was made but not kept, after the last call, no more follow-up will be conducted.

3.4. Tailored navigation (TN) and/or no navigation control arm Phase II

Once the clinic appointment has been made and kept, regardless of their original study arm assignment, the participant will be called/tracked in order to meet them at the clinic appointment, or call and confirm appointment, and to ask additional questions to confirm insurance status, payment/co-pay made, repeat questions to address perceptions of having a medical home and prior screening status, and transportation/distance traveled to appointment. CHNs will continue to call once a participant from either arm of the study attends the clinic (blinded to study arm assignment) to tailor their navigation efforts to assist patients to overcome barriers to care, negotiate healthcare systems, and access quality care [12]. Calls will continue for a total of 5 within a 10-week period, with continued recording in our database of barriers and tailored responses.

3.5. Standardization and fidelity of TN

Standardization and fidelity of TN will be maintained by staff training, utilizing role-play with the navigation scripts for tailored responses, observation, and checklists for feedback to assure consistency of content and delivery [48]. The differences between the two navigation phases are that in Phase I, the TN messages will focus on barriers identified in our pilot study as being obstacles to choosing to getting screened, accessing primary care and attending clinic appointments. The navigation messages used for tailoring in Phase II will be focus more on the logistics of following through on CRC screening and strategies to deal with obstacles navigating the health care system. Both tailored navigation sets of responses will be drawn from the larger message library, and will be adapted as needed for the current contexts.

3.6. Special considerations for patients at high risk

Participants are considered to be at high risk for CRC if they meet one or more of the following criteria: First degree relative (FDR) with CRC, age of FDR’s, prior CRC diagnosis, personal history of CRC, personal history of adenomatous polyps, history of inflammatory bowel disease. The current recommendation for individuals at high risk for CRC is to bypass the less invasive annual stool testing and have a colonoscopy [50]. We considered eliminating high-risk patients from the study, but because of the translational goals of this project, we chose to keep them in the study and provide an accelerated plan of action to increase the likelihood that they would receive colonoscopy services. In population-based estimates, about 25% of CRC is diagnosed in those at high risk [46]; we anticipate 5% or less of the study sample will be high risk (based on estimates provided by two of the larger FQHCs aligned with the study). Risk status will be used as a covariate in final analyses.

3.7. Accelerated approach for high-risk patients in Phase I GE only

Participants identified as high risk will receive specific information on colonoscopy in a handout with an explanation about why it is especially important for them to receive this test. The handout instructs the participant to call their doctor’s office or clinic, as well as a number to call for facilities offering colonoscopy. This is a responsible approach, emphasizing critical information and call to action, and is more than is typically done in studies that exclude high risk individuals.

3.8. Accelerated approach for high-risk patients in Phase I GE ± TN

The accelerated approach will continue in the next phase of the study once patients get into a clinic, similarly allowing for additional calls and longer time periods for high-risk patients. All of the above will be followed; plus, special TN scripts will be used to address barriers to colonoscopy, continuing past the initial 5 calls (up to 10) to move people into the clinic setting.

4. Outcome measures

4.1. Phase I

The primary outcome (Phase I) is attendance at a primary care clinic. This information is gained first through self-report (in person meeting at the clinic site, or by phone), but also from the information provided by calls or visits to the clinic. Referral from the provider and/or refusal to accept FIT/FOBT kit (or colonoscopy referral) will be documented.

4.2. Phase II

The secondary outcome (Phase II) is completion of screening test. The secondary outcome is adherence to a referral for CRC screening, de-fined as a completed screening that was referred (FIT/FOBT or colonos-copy). Thus, confirmation of referral is important to determine the appropriate denominator in assessing results. Participants will have completed tests when the test kit is returned (mailed, brought to clinic, etc.) and that information is recorded in the patient’s chart. Self-reported screening test completion will be verified by medical record review (obtained from clinic staff) adding to the accuracy of the outcome measurement. While we will document results of the screening test, additional diagnostic testing and possible treatment are beyond the purview of this study. Participants will be in the primary care system and followed by their provider. Navigators will be trained to encourage participants to communicate with their primary care providers and follow through with next diagnostic steps and treatments. Clinic partners have systems in place for follow-up on CRC screening (and are, in fact held accountable for the follow-up plan and resources as part of maintaining engagement in the study).

4.3. Chart confirmation of referral and CRC screening

All participants are invited on the informed consent form to agree to our follow-up calls to their clinic or provider to obtain information regarding their CRC screening completion. The calls to clinics to obtain reports over the phone to confirm reported screening outcomes will be conducted at 3 and 6 months post-intervention for those who kept an appointment. We anticipate that some of our participants will attend clinics that are not part of our system of research partners, having already established a medical home elsewhere. In those cases, we will, contact the clinic, present the patient consent, and obtain reports of CRC screening or not.

4.4. Patient-reported screening

Questions from the NCI-recommended and tested Core Questions to Measure Colorectal Cancer Screening Behaviors (developed by a working group sponsored by the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences of the NCI) will be used with adaptations and translated [51]. We have used this tool in the past with low-income patients in safety-net clinics, and we have added procedural descriptions and definitions of terms (in English and Spanish) to be sure that patients understand the type of screening being queried.

4.5. Resolution of inconsistent patient reported screening vs. chart reports

A confirmed chart report will be compared to patient reports, and if patient report does not match, the patient will be called to probe again for confirmation so that (a) possible errors in the chart could be addressed (e.g., wrong report) and (b) if chart is confirmed to be correct, then to use the opportunity to educate the patient. If the patient report is missing (lost to follow-up), the chart record of screening will be accepted.

5. Data collection

5.1. Eligibility and baseline Phases I and II

Eligibility status will be determined using initial screening information, including CRC screening history/status, age, date of birth, gender, race, and ethnicity, as well as education, income and insurance (including what, if any coverage, private, Medicaid or sliding scale, or “notch group”, i.e., unable to obtain insurance either due to financial reasons or lack of documentation). Participants who we determine to be ineligible will be thanked for their time, encouraged to continue with CRC screening annually (or on whatever schedule appropriate based on risk status, age and type of screening obtained) those who are eligible will be interviewed for baseline data collection. The additional demographic data to be collected at baseline will include marital status, and number of adults and children in household. CRC risk status will be obtained as described above to determine eligibility and serve as baseline CRC screening data. Detailed contact information will be obtained (including relatives, alternate phones and addresses) to facilitate follow-up.

5.2. RE-AIM data collection

Process tracking forms will be created to record the following data (where this information is not already part of outcome and cost data) and will be collected by study staff throughout the project. These data will be used to create descriptions, reports and discussions regarding the multi-level aspects of dissemination strengths and weaknesses of the project (Table 1).

Table 1.

Source, data, and analysis for RE-AIM Evaluation.

| FACTOR | Source | Data | Reporting/analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | Community sites | # of sites accessed and number of people/description at each site potentially accessed (e.g., membership in a church aged 50–75), # reached (how many attend intro presentations) | Descriptive tables |

| Census data | Sample representativeness based on census data of low-income population profile | Compare population profiles to accessed sites/site profiles and participants reached in study | |

| Effectiveness | Clinics | # attend clinics (Phase I outcome), # who obtain screening (Phase II outcome); “Effectiveness” assessed as function of intervention arm compared to control for Phase I and completion of screening test for Phase II; demographic data for each | Descriptive tables & data from hypothesis testing integrated into RE-AIM frame |

| Adoption | Community sites Clinics | # of community sites that adopt interventions (classes, navigation) and # of clinics that adopt navigation | Assess outcomes relative to population representativeness Descriptive tables |

| Implementation | Community sites Clinics | Process tracking: # in study (consented/randomized), # of classes conducted, navigation calls from community & clinic sites, appointments made/kept; GE curriculum; TN library will be provided to community sites and clinics to use if they choose to continue | Descriptive tables |

| Maintenance | Community sites Clinics | 3-month post-intervention assessment at each site and clinic will be conducted to track any continued activities, e.g., classes, navigation | Activities unlikely to continue without funding, but this will be assessed and discussed as part of CEA and need for policy/funding |

5.3. Data collection for cost-effectiveness analysis

Data for the cost analyses will be drawn from study and clinic records and tracked separately for each phase of the study. Costs associated with contact with community and clinic sites, TN intervention, CHN training, GE class training, scheduling and implementation will be tracked, and distinguished and separated from costs associated with the research-only time and expenses. Each staff member will have detailed categories for time spent created within their daily calendars so that logs of activities related to the intervention arm comparisons can be made, accounting for salary and other expenses spent for both phases of the study. We will also capture the number of clinic appointments made and kept.

The Cultural Community Advisory Board and research team reviews for multicultural materials/procedures. Although recruitment protocols, TN scripts, and data collection instruments have all been used in low-income, multicultural populations by this team, the advisory board and research team will review these procedures and materials. Many of the written materials and scripts have already been translated from Spanish to English or from English to Spanish (depending on the language of origin and past study designs), have had the content equivalence in both languages verified through back-translation, and then utilized in community and clinic interventions. Any new materials will be translated and back-translated and reviewed by the Cultural Community Advisory Board. Each cultural “member” (that is, those of the race/cultural group on the advisory board and those on the research team with specific experience in cultural communication adaptation of educational material) will consider content (information, wording, and translations) and approaches (who introduces staff in what setting, etc.) for cultural appropriateness, for all materials and messages and adjustments will be made according to recommendations.

5.4. Training staff

The program coordinator and all staff will be trained by Drs. Menon and Larkey (overseen by the research team) in basic research principles and study goals, HIPAA, Human Subjects Protection certification, and the study protocol (for TN). Web-based data entry protocols using laptops will be pre-programmed, and training on use of computer system for data entry of baseline/demographic data and ongoing tracking of intervention (calls, barriers/TN messaging, self-reported outcomes) will be included in training. All data collectors/interviewers will receive a full-day, general interviewer training adapted from previous training protocols developed by Dr. Menon. These combined trainings will prepare interviewers to uniformly consent participants and conduct baseline interviews prior to classes.

5.5. Establishing protocols in partnership with collaborating clinics

A number of clinics and healthcare systems with clinics have agreed to join in this study, representing most of the safety-net clinics in our county. These clinics serve the most underserved in our county, located in neighborhoods where the highest concentrations of low-income and under-screened persons live. Each clinic system will be addressed separately to coordinate most efficient procedures. Our core research staff will work closely with representatives, including clinic managers, healthcare providers, and front/back office staff at start-up and then meet regularly as the program rolls out at each system’s clinics. After initial meetings and agreements with clinic representatives, orientations to all clinic staff will be conducted to introduce the full project and purpose, query staff for best ways to implement with front and back office staff so as not to interfere with patient flow, coordinate tactics to track patients who call in from the community intervention (as was done in the Navigation Pilot project), and carry out standardized follow-up procedures.

5.6. Patient follow-up

We anticipate that a small number of participants (8–10%, based on past work within this population) will need additional diagnostic care/follow-up. Each clinic has its own system of referrals for treatment and follow-up care using a combination of the county health system, charity care, and arrangements with private health systems, a requirement of FQHCs to maintain funding. It is beyond the scope of this project to provide diagnostic and treatment follow-up; therefore, our patient navigators will inquire at each follow-up point and assure that the patient is connected to the appropriate case-worker within that particular system for follow-up care.

6. Statistical analysis

6.1. General analytic approach

Our data analysis plan begins with descriptive analyses and culminates in testing complex multilevel models predicting, primarily, appointment completion and, secondarily, CRC screening completion. After data cleaning, we will calculate descriptive statistics to ensure the quality of the data (check distributions, examine outliers) and to describe the sample (e.g., age, education, annual income, marital status). We will examine the nature of missingness in the data and, if necessary, will conduct analyses using Multiple Imputation (SAS 9.2) in which 10 sets of data will be imputed randomly using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo mechanism. Ten independent sets of analyses will be conducted. The results of this analysis will be combined to obtain a final set of estimates [52]. We will estimate correlations among all variables and conduct contingency table analyses, independent t-tests and ANOVA models to examine differences between the GE and GE + TN intervention groups for Phase I and site-level differences, and clinic-level differences for Phase II.

H1

Individuals receiving General Education (GE) and Tailored Navigation (TN) will show higher rates of clinic attendance (60%) than those receiving only GE (20%), we will first assess intervention differences in appointment completion (Phase I) with contingency table analyses. We will then model appointment completion using a multilevel random effects logistic regression model using PROC NLMIXED (SAS). In this approach, the influence of GE + TN (intervention) on appointment completion is included through both an intervention-level fixed effect and a random effect (note that we will also include a clinic-level–where the appointment was kept–fixed effect and random effect). The model is expressed by the following equation

where j γ ~ i.i.d. N(0,1), and 2 g σ ij π is the expected probability of appointment completion for the jth individual of the ith intervention group conditional on the predictor variables and the random effect. The model will then be extended to include demographic controls and risk related predictors. High risk, family history, age, racial/ethnic group and site type will be controlled for in multilevel models and subsequent sensitivity analyses will be conducted to determine their impact on estimated parameters.

The advantages of fitting a multilevel random effects logistic regression model include our ability to examine effects at the intervention level, the site level and at the individual level, controlling for clustering. The advantage of using NLMIXED (rather than GLIMMIX) is that it produces a true log-likelihood fit statistic that can be used to compare nested models and that it uses the maximum likelihood estimation methods [53].

H2

Individuals receiving General Education (GE) and Tailored Navigation (TN) will show higher rates of CRC screening completion than those receiving only GE, our analyses will parallel those for Aim 1; that is, after examining differences in CRC screening (Phase II) with contingency table analyses, we will model CRC screening with a multilevel, random effects, logistic regression model using PROC NLMIXED.

6.2. Cost effectiveness aim

We will first calculate the incremental cost per additional participant keeping a clinic appointment of GE + TN versus GE. This analysis will compare the additional cost (mainly staff, travel and materials costs) of providing GE + TN over providing GE only to the additional clinic appointments achieved between the two groups. Then we will calculate the incremental cost per additional person screened between GE + TN and GE. This analysis will compare the additional costs incurred by the GE + TN group versus the GE group to the additional CRC screening achieved. For this analysis all costs from the community groups through screening will be counted including the costs of clinic visits and of screening, if these were incurred. All analyses will be performed from the perspective of the healthcare system, assuming that this system would also offer the navigation services [54]. Finally, the incremental cost per additional person screened will be compared to the most current estimates of the future CRC-related healthcare costs avoided/saved by screening. For example, a 2009 study by Lang et al. found that detecting CRC at an earlier stage not only improves survival but lowers treatment costs. Stage IV CRC patients incurred $31,000 in excess costs per survival year compared with $3000 for Stage 0 patients. Resource use in each cost category (i.e., hours of navigation staff time and number of clinic visits and screenings of each type) will be reported and valued separately to allow future decision makers to apply their own unit costs if different. Staff time will be valued at the actual average cost per hour for salary plus benefits. Standard Medicare reimbursement rates will be used to value clinic visits and each of the different types of CRC screenings received [55,56]. Sensitivity analyses will be used to determine the robustness of results to variations in each cost component and to the uncertainty surrounding effectiveness results (e.g., across the confidence interval range for the difference in clinic appointments and screening rates).

7. Dissemination analysis

7.1. Dissemination aim

Examine the levels of program dissemination and success from community to clinic to CRC screening using the RE-AIM model: What is the degree of Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance of the community-to-clinic navigation, and clinic-to-screening outcomes? Descriptive statistics will be estimated to discuss achievements across the components of the RE-AIM framework for each site. We will develop a demographic profile for the populations accessed and reached in both Phases I and II. We will use contingency table analyses and independent t-tests to compare the study demographic profiles to the demographic characteristics of the general population of Maricopa County, annually, using data from the US Census. We will use contingency table analyses and independent t-tests to compare the study screening rates to the screening rates of the general population of Maricopa County annually, using data from CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data for Maricopa County. Finally, we will fit repeated-measures ANOVA models to examine any changes in screening practices over time for Maricopa in general and compare it with our screening completion rates.

8. Discussion

The strengths of this study include the application of the co-PIs prior research that both identify gaps and provide evidence for what works, as well as build on the potential of practical dissemination opportunities for pragmatic application, cost assessment and contributions to policy.

8.1. Combining prior evidence to bridge a gap

Our proposed study uniquely unites elements that have already been successful in studies completed by the two co-PIs to test a simple and potentially cost-effective method for reaching the truly hard-to-reach for CRC screening increasing the translational value of our research. Evidence from our own clinic and community studies have been combined in the current study to bridge a gap found when community interventions perform relatively poorly for achieving screening, while clinic-based studies achieve better rates of screening with patients already looped into a medical home. We are expanding these interventions to test in a randomized, controlled trial in a low-income, underinsured, multicultural population in the greater Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area to examine effectiveness and cost relevance to large-scale dissemination, within the context of referral to primary care services and providing the opportunity for a medical care home.

Research regarding reaching people in community settings with messages of cancer screening generally documents improvements in knowledge and intention [57]. The actual rates of screening, however, are often not documented, or if reported, based on self-report, are generally low [58], sometimes not significantly improved over the comparison intervention [59,60] or no intervention [61] (with some exceptions, such as 91% screening rate using intensive combined interventions and follow up) [57]. Even in our own prior studies utilizing community health workers to promote cancer prevention and screening messages among over a 1000 very low-income participants in Arizona, we found extremely low rates of ever having been screened for CRC (4–9%) [62,63]. This finding, compared with our experience in clinic settings where, once providers referred patients, rates of screening were 34–79% [64,65], suggests a large gap between the reach capacity of screening promotion in community settings and the clinic context. It is this gap that our study primarily addresses. To our knowledge, there has been no prior research testing tailored navigation from community settings directly into clinics to facilitate CRC screening, except for our pilot study that tripled screening rates among those who were navigated from the community into clinics compared to those not receiving navigation.

Three major differences of this study compared to the pilot study are (a) separating the steps in two phases to better unpack understanding of the achievements of tailored navigation, to obtain and keep a clinic appointment and then to proceed through to complete CRC screening, (b) sample size, that is, 266 planned groups/1840 participants to be recruited instead of only 11 groups and 34 participants per arm of study (for a total of 22 groups and 68 participants), so as to better interpret results from a fully powered study, (c) recruiting groups prospectively and randomizing prior to interventions (rather than matched controls), and (d) tracking data to evaluate cost per screening so as to gain sufficient evidence of effectiveness and costs of this dissemination that could inform policy regarding tailored navigation.

8.2. Dissemination study strengths

As a dissemination study, we include the most practical field applications of the prior interventions to keep implementation streamlined and suitable for pragmatic assessment. The theoretical bases of the TN intervention have been previously tested. As such, the current proposal does not include measurement of and testing of theory-related factors. Rather, as a test of broader dissemination from the community to the clinic and finally to individual CRC screening adherence, the implementation aspects of this study are being evaluated for dissemination potential and costs. Evaluation includes the reach, effectiveness, adoption, and implementation of our navigation program [66]. Our study, then, is designed across multiple health settings and levels by combining the strengths of previous programs in an inventive way that we anticipate will lead to appropriate cancer screening in vulnerable populations [12,67].

The proposed study meets several national health priorities, including the emphasis of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on reducing cancer-related disparities and the continued need to increase CRC screening to realize the full benefits of early detection. Community-engaged health promotion is able to target specific underserved areas and reach people who may not have a primary care home, but this advantage of reaching the most underserved is offset by the difficulty of moving people into the clinic to obtain screening. Clinic-based initiatives reach people where follow through is more likely, but many of those who are hardest to reach do not come into the clinic in the first place. Our study is designed to cut across these challenges and navigate from community to clinic and continue to CRC screening.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funded by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (1R01CA162393-01A1).

Footnotes

Funding for this study is provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Grant Number: 1 R01 CA162393-01A1.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute (NCI) The colorectal progress review report. http://progressreport.cancer.gov/doc_detail.asp?pid=0&did=0&chid=72&coid=718&mid=2000 (Accessed February 1 2008)

- 2.Richardson LC, Rim SH, Plescia M. Vital signs: Colorectal cancer screening among adults aged 50–75 years United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2010. 2008;59:1–4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http:www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5926a3.htm?s_cid=mm5926a3_w. Updated 2009. Accessed August, 31, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable. 80% by 2018 Pledge. http://nccrt.org/tools/80-percent-by-2018/80-percent-by-2018-pledge/ (Accessed October 23, 2016)

- 5.National Cancer Institute (NCI) Colorectal cancer screening in primary care practice (PAR-02-042) http://www.grants1.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-02-042.2002 (Updated 2001. Accessed January 24, 2008)

- 6.Myers RE, Hyslop T, Sifri R, et al. Tailored navigation in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S123–S131. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Percac-Lima S, Grant RW, Green AR, et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):211–217. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis C, Pignone M, Schild LA, et al. Effectiveness of a patient- and practice-level colorectal cancer screening intervention in health plan members: design and baseline findings of the CHOICE trial. Cancer. 2010;116(7):1664–1673. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane DS, Messina CR, Cavanagh MF, Chen JJ. A provider intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in county health centers. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S109–S116. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d3fcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling BS, Schoen RE, Trauth JM, et al. Physicians encouraging colorectal screening: a randomized controlled trial of enhanced office and patient management on compliance with colorectal cancer screening. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nease DE, Jr, Ruffin MT., IV Impact of a generalizable reminder system on colorectal cancer screening in diverse primary care practices: a report from the prompting and reminding at encounters for prevention project. Med Care. 2008;46(9):S68–S73. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817c60d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, Christie J, Itzkowitz SH. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82(2):216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon U, Belue R, Wahab S, et al. A randomized trial comparing the effect of two phone-based interventions on colorectal cancer screening adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):294–303. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wender RC, Altshuler M. Can the medical home reduce cancer morbidity and mortality? Prim Care. 2009;36(4):845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Malley AS, Renteria-Weitzman R, Huerta EE, Mandelblatt J, Latin American cancer research coalition Patient and provider priorities for cancer prevention and control: a qualitative study in Mid-Atlantic Latinos. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregg J, Curry RH. Explanatory models for cancer among African-American women at two Atlanta neighborhood health centers: the implications for a cancer screening program. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(4):519–526. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Boyd MD, Johnson E, Frank-Stromborg M. Knowledge of colorectal cancer among older persons. Cancer Nurs. 1992;15(5):322–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf RL, Zybert P, Brouse CH, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and barriers relevant to colorectal cancer screening in an urban population: a pilot study. Fam Community Health. 2001;24(3):34–47. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(19):1406–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faivre J, Arveux P, Milan C, Durand G, Lamour J, Bedenne L. Participation in mass screening for colorectal cancer: results of screening and rescreening from the burgundy study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1991;1(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin D. A model for describing low-income African American women’s participation in breast and cervical cancer early detection and screening. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1996;19(2):27–42. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denberg TD. Re: racial/ethnic disparities in the treatment of localized/regional prostate cancer. J Urol. 2004;172(4 Pt 1):1547–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)61227-x. (author reply 1548) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis C, Cohen RS, Apolinsky F. Providing social support to cancer patients: a look at alternative methods. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2005;23(1):75–85. doi: 10.1300/J077v23n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS. Impacting cultural attitudes in African-American women to decrease breast cancer mortality. Am J Surg. 2002;184(5):418–423. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snow BW, Rowland RG, Donohue JP, Einhorn LH, Williams SD. Review of delayed orchiectomy in patients with disseminated testis tumors. J Urol. 1983;129(3):522–523. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris DM, Miller JE, Davis DM. Racial differences in breast cancer screening, knowledge and compliance. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(8):693–701. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown ML, Potosky AL, Thompson GB, Kessler LG. The knowledge and use of screening tests for colorectal and prostate cancer: data from the 1987 national health interview survey. Prev Med. 1990;19(5):562–574. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90054-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price JH. Perceptions of colorectal cancer in a socioeconomically disadvantaged population. J Community Health. 1993;18(6):347–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01323966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers RE, Trock BJ, Lerman C, Wolf T, Ross E, Engstrom PF. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an HMO population. Prev Med. 1990;19(5):502–514. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90049-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers RE, Ross EA, Wolf TA, Balshem A, Jepson C, Millner L. Behavioral interventions to increase adherence in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 1991;29(10):1039–1050. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herbert C, Launoy G, Thezee Y, et al. Participants’ characteristics in a French colorectal cancer mass screening campaign. Prev Med. 1995;24(5):498–502. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arveux P, Durand G, Milan C, et al. Views of a general population on mass screening for colorectal cancer: the burgundy study. Prev Med. 1992;21(5):574–581. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90065-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King J, Fairbrother G, Thompson C, Morris DL. Colorectal cancer screening: optimal compliance with postal faecal occult blood test. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62(9):714–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menon U, Champion VL, Larkin GN, Zollinger TW, Gerde PM, Vernon SW. Beliefs associated with fecal occult blood test and colonoscopy use at a worksite colon cancer screening program. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(8):891–898. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000083038.56116.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinney AY, Emery G, Dudley WN, Croyle RT. Screening behaviors among African American women at high risk for breast cancer: do beliefs about god matter? Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(5):835–843. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.835-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holm CJ, Frank DI, Curtin J. Health beliefs, health locus of control, and women’s mammography behavior. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22(2):149–156. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larkey L, Menon U, Szalacha L. Community-to-clinic tailored navigation for colorectal cancer screening. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(Supplement 1):S177. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larkey LK, Gonzalez JA, Mar LE, Glantz N. Latina recruitment for cancer prevention education via community based participatory research strategies. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral risk factor surveillance survey (BRFSS), 2008, division of adult and community health, national center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion, centers for disease control and prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention & Health Promotion Web site. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/income.asp?cat=CC&yr=2008&qkey=4424&state=AZ Updated 2008. Accessed August 31, 2010.

- 41.Larkey LK, Lopez AM, Minnal A, Gonzalez J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: a randomized pilot study. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):79–87. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeller R, Good M, Anderson G, Zeller D. Strengthening experimental design by balancing potentially confounding variables across treatment groups. Nurs Res. 1997;6:345–349. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menon U, Belue R, Wahab S, Rugen K, Kinney AY, Maramaldi P, Wujcik D, Szalacha LA. A randomized trial comparing the effect of two phone-based interventions on colorectal cancer screening adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):294–303. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition. J Educ Behav Stat. 1999;24:70–93. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: Update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(19):1462–1470. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–669. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menon U, Szalacha LA, Belue R, Rugen K, Martin KR, Kinney AY. Interactive, culturally sensitive education on colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008;46(9 Suppl 1):S44–S50. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818105a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;2009 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahnen DJ, Bastani R, Shenfield GS, et al. Core questions to measure colorectal cancer screening behaviors. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/acsrb/CRCS_core_questions.pdf (Updated 2006. Accessed October 19, 2010)

- 52.Croy CD, Novins DK. Methods for addressing missing data in psychiatric and developmental research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(12):1230–1240. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181044.06337.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociol Methodol. 1995;25:295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, OBrien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. third. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare clinical laboratory fee schedule. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/ (Updated 2016. Accessed October 30, 2010)

- 56.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare physician fee schedule. CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/index.html (Updated 2016. Accessed October 30, 2010)

- 57.Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Stromborg MF, Boyd MD, Weiss HL. Using elderly educators to increase colorectal cancer screening. Gerontologist. 1993;33(4):491–496. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Danao LL, Antonio C, Garcia GM, Crespi CM. Results of a community-based randomized trial to increase colorectal cancer screening among Filipino Americans. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2228–2234. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janda M, Hughes KL, Auster JF, Leggett BA, Newman BM. Repeat participation in colorectal cancer screening utilizing fecal occult blood testing: a community-based project in a rural setting. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Oct;25(10):1661–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2009 Jun;181 (1-44, A1-2, B1-14) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson SL, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas Cancer Education and Screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1602–1610. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larkey LK. Las mujeres saludables: reaching Latinas for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer prevention and screening. J Community Health. 2006;31(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-8190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larkey LK, Herman P, Roe D, Gonzalez J, Garcia F, Lopez AM, Pepera P, Saboda K. A cancer screening intervention for underserved Latina women by lay educators. J Womens Health. 2012;12(5):1–10. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Larkey LK, McClain D, Roe DJ, Hector RD, Lopez AM, Sillanpaa B, Gonzalez J. Randomized controlled trial of storytelling compared to a personal risk tool intervention on colorectal cancer screening in low-income patients. Am J Health Promot. 2015 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.131111-QUAN-572. 150123091432001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larkey LK, Wilson J, Sillanpaa B, et al. Effect of risk discussion source and perceptions of provider communication style on patient compliance with CRC screening in primary care clinics. Ann Behav Sci Med Educ. 2009;15(2):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]