Abstract

Organismal aging is accompanied by a host of progressive metabolic alterations and an accumulation of senescent cells, along with functional decline and the appearance of multiple diseases. This implies that the metabolic features of cell senescence may contribute to the organism’s metabolic changes and be closely linked to age-associated diseases, especially metabolic syndromes. However, there is no clear understanding of senescent metabolic characteristics. Here, we review key metabolic features and regulators of cellular senescence, focusing on mitochondrial dysfunction and anabolic deregulation, and their link to other senescence phenotypes and aging. We further discuss the mechanistic involvement of the metabolic regulators mTOR, AMPK, and GSK3, proposing them as key metabolic switches for modulating senescence.

Keywords: Glycogenesis, Lipogenesis, Metabolic regulators, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Protein synthesis

INTRODUCTION

Cell senescence is an irreversible state of cell cycle arrest induced by multiple stressors, such as DNA damage, oncogenic activation, oxidative stress, and chemotherapeutic toxicity (1, 2). Observations of senescent cell accumulation in aged tissues (3) have led to the assumption that cell senescence may play an important role in the organismal aging process. A causal link between cell senescence and aging was first demonstrated by studies performed in a rapidly aging mouse model with a BubR1 deficiency (4). In this model, p16INK4A-positive senescent cells accumulated in prematurely aged tissues, and the genetic inactivation of p16INK4A attenuated the formation of senescent cells and the development of aging phenotypes, emphasizing cell senescence as a fundamental aging mechanism. Recently, a number of studies have described that cellular senescence was also involved in various age-associated diseases, such as atherosclerosis, fibrotic pulmonary disease, hepatic steatosis, osteoarthritis, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease (5–8), suggesting that cell senescence may causally drive these diseases. However, the mechanism by which cell senescence is involved in these age-associated diseases is unclear. A detailed understanding of the characteristics of cell senescence may be the key to elucidating this issue.

In addition to the irreversible cell cycle arrest, senescent cells exhibit apparent alterations of cellular morphology and functionality, such as an enlarged and flat cellular morphology, release of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), and a resistance to apoptosis. These features distort cellular communications with surrounding cells and tissues, eventually leading to tissue reorganization and deterioration (3, 9). The functional alterations of senescent cells come from abnormalities in morphology, mass, and the functions of their organelles, such as mitochondria, lysosomes, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), nucleus, etc. Although each organelle possesses its own function and metabolism, senescent organelles share some common changes, including increases in their subcellular mass with functional defects and modified communication through release of their metabolites (10). These organelle abnormalities are indicated by several typical senescent markers, such as respiratory defects and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria, an increase in senescence-associated-β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-Gal) and lipofuscin in lysosomes, an unfolded protein response (UPR) in the ER, and senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) and DNA damage response (DDR) in the nucleus. However, it remains uncertain how the overall mass of cellular organelles increases as senescence progresses, and leads to defective functions. This underlying mechanism must be closely linked to senescence-associated metabolic changes and there must be a key player that modulates organelle mass during senescence.

In this paper, we reviewed key metabolic features of cellular senescence. In particular, we focused on mitochondrial catabolic defects and deregulated anabolic activation, and their links to the subcellular organelle features of senescence. We also reviewed some key players in the metabolic alterations and their potential links to age-associated diseases.

METABOLIC FEATURES OF CELL SENESCENCE

Cellular metabolism is usually categorized as two opposite directions of energy flow: catabolism, the oxidative degradation of macromolecules that generates cellular energy as ATP; and anabolism, the reductive synthesis of the macromolecules for building cell components (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates) that consumes the energy. The major catabolic activity is glucose oxidation, which is tightly linked to mitochondrial respiration. Anabolic activities take place in different organelles, depending on the types of macromolecules generated. Normal cells maintain the controlled balance between cell division and cell metabolism, because optimal building of cell components and maintenance of cellular energy levels are essential for cell division activity. And, despite the permanently arrested state of cell growth, senescent cells remain metabolically active, but in an altered state (11). Therefore, it is very important to explore the metabolic changes critically involved in cellular senescence to understand the underlying mechanisms of senescence, the aging process, and age-associated metabolic diseases.

MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION AND ITS LINK TO DNA DAMAGE RESPONSES

Oxidative phosphorylation dysfunction in aging

In an aerobically growing cell, mitochondria play a key role in producing and maintaining cellular energy (ATP). This is achieved by a complex sequential reaction, named oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which is composed of four respiratory chain complexes (complex I to IV), and F1F0-ATP synthase (complex V) embedded in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Human cells harbor hundreds to thousands of mitochondria, depending on the cell type, and the mitochondrial mass and activity are susceptible to the cellular energy needs of cell growth and differentiation, and physiological conditions, such as endurance exercise. Deterioration in the mitochondrial OXPHOS function during human aging has been reported (12). The causal link between OXPHOS function and aging was demonstrated in mev-1 (ortholog of the complex II cytochrome b560 subunit) mutant nematodes. Mitochondrial defects caused by the mev-1 mutation resulted in oxidative stress and premature aging in Caenorhabditis elegans (13). In addition, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions or mutations have been associated with aging and certain age-related diseases in animals (14–16). The involvement of mtDNA damage in aging was mechanistically proven by studies of mice harboring defective proofreading activity of mtDNA polymerase. These mice exhibited accumulation of mtDNA mutations and premature aging (17). These two studies well support “the mitochondrial theory of aging” (18, 19).

OXPHOS dysfunction in cellular senescence

The potential involvement of mtDNA damage in cellular senescence has also been reported (20). Mitochondrial DNA-depleted rho(0) MDA-MB-435 cells displayed senescent phenotypes, such as SA-β-Gal, lipofuscin pigment, and decreased telomerase activity (20). Thus, the rho(0) cells can be used as an in vitro model for aged cells. Several different mitochondrial OXPHOS defects were demonstrated in the early stages of the senescent process using diverse cellular senescence models. Iron chelation using deferoxamine (DFO) decreased complex II activity via down-regulated translation of the complex II iron-sulfur subunit, prior to increasing p27kip1-mediated cell cycle arrest, and eventual induction of senescence in Chang normal liver cells (21, 22). Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF β1) triggered senescence of Mv1Lu lung epithelial cells by inhibiting complex IV activity via the PKCδ/GSK3 axis, and increasing ROS (23–25). Ionizing radiation induced endothelial cell senescence through a mitochondrial respiratory complex II defect and superoxide generation (26). Mitochondrial dysfunction was also involved in hydrophobic bile acid-induced human trophoblasts (27). These findings emphasize that mitochondrial OXPHOS dysfunction is primarily involved in cellular senescence, regardless of the types of senescent stressor.

Senescent features of mitochondrial dynamics

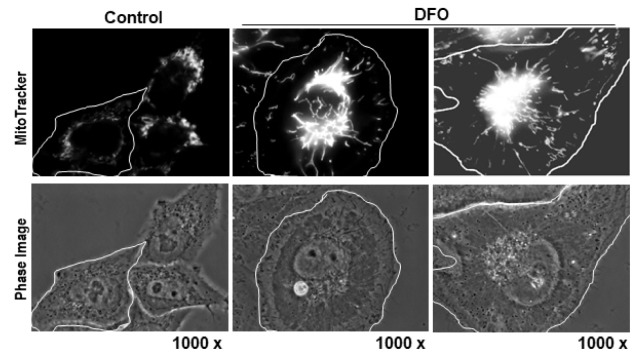

In addition to OXPHOS dysfunction, special mitochondrial alterations are observed in cell senescence. Pleomorphic giant or highly interconnected mitochondria have often been reported in cirrhotic livers and in several aged tissues (28, 29). Also, progressive elongation of mitochondria (Fig. 1) was clearly visualized in the DFO-induced senescence, accompanied by a complex II defect (30). This study also showed that many differently induced senescent cells harbored giant elongated mitochondria, and downregulation of Fis1, a mitochondrial fission modulator, was the key underlying molecular mechanism. Why are enlarged mitochondria formed during cellular senescence or aging? Mitochondrial fusion drives extensive complementation to maintain homogenous inheritance to progeny (31), efficient transfer of energy or signaling (32), and to preserve the function of randomly damaged individual mitochondrion (33, 34). The last hypothesis seems appropriate to explain the giant enlarged mitochondria displayed in senescent cells because these mitochondria already possess an OXPHOS defect. Interestingly, abrogating mitochondrial dynamics accelerated mitochondrial senescence in mice (35), supporting the importance of morphological dynamics in the aging process. One plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that maintenance of the proper size of mitochondria is essential for its quality control, because giant damaged mitochondria have difficulties during autophagic degradation (36, 37).

Fig. 1.

Alterations of mitochondrial morphology and mass in cellular senescence. Images of senescence in Chang cells induced by 1 mM DFO, stained with MitoTracker Red and visualized with an Apo Plan 1000 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.4) on an Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). Highly interconnected elongated mitochondria with increased mass are shown.

Another feature of mitochondrial senescence is an increase in cellular mitochondrial mass (Fig. 1). Simultaneous with formation of giant elongated mitochondria, mitochondrial mass also progressively increased in several cellular senescence models induced by DFO, TGF β1, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and replicative stress (30, 38). We can simply assume that damaged enlarged mitochondria are accumulated during the senescent progress due to their insensitivity to autophagic degradation. However, it remains unclear whether this is the only explanation. In normal growth conditions, the number of mitochondria is well controlled and, even in cell division, the mitochondrial mass per cell is properly maintained in the progenies, implying there is intimate control of the number within individual cells. Senescent cells may lose this control, resulting in a progressive increase in mitochondrial mass, despite their functional defects.

Mitochondrial retrograde signaling and senescence

How does mitochondrial OXPHOS dysfunction regulate senescence and aging? The answer to this question is important for determining whether the mitochondrial dysfunction is merely an epiphenomenon or has causative roles in the course of senescence and aging. When the activities of mitochondria are altered, communication with the nucleus via mitochondrial retrograde signaling, which is initiated from mitochondria and sent to the nucleus and is often reported in mitochondrial damage-associated conditions, such as cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular diseases (39–41). The retrograde signaling starts with several key events: diffusion-mediated release of ROS, transporter-linked release of calcium ions into the cytoplasm, and alterations in the NAD+/NADH and ADP/ATP ratios (42). These signals activate diverse cytosolic transducers through oxidative modification; interactions with small molecules, such as Ca++, NAD+, or AMP; and various post-translational modifications, then transmit into the nucleus (42, 43). There, the transducers modulate the activities of certain transcription factors, including PGC1α, Sirt1, mTOR, and CREB, switching on transcriptional reprogramming (42). The reprogrammed transcripts may restore mitochondrial function, activate an alternative energy supply, modify cellular function, and change cellular fate to death, senescence, or proliferation (42, 44–47). Thus, retrograde signaling-mediated transcriptional reprogramming may play a key role in senescence and aging (Fig. 2).

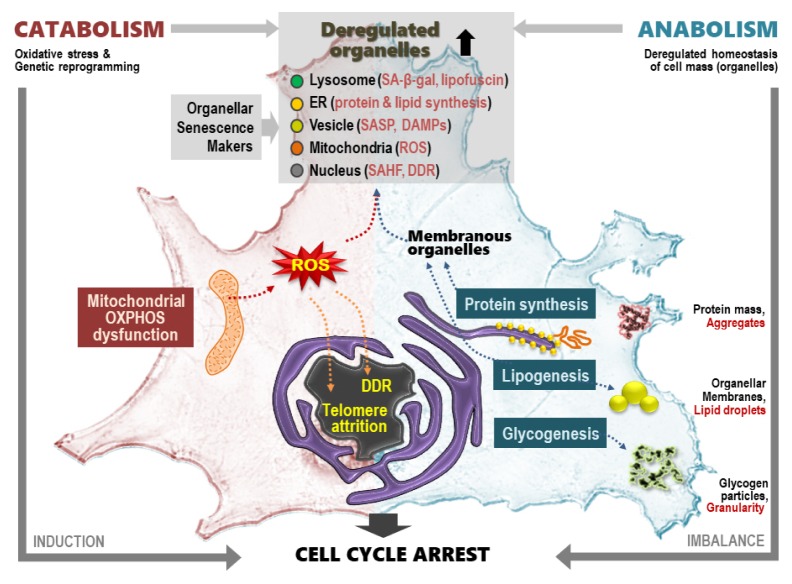

Fig. 2.

Summary of metabolic features and related key senescent phenotypes in cellular senescence.

Mitochondrial ROS, oxidative stress, and the DNA damage response

Among the mitochondrial retrograde signaling messengers (such as ROS, calcium, NAD+, and AMP), ROS has long been implicated in senescence and aging. ROS not only mediate retrograde signaling, but also directly damage DNA, proteins, and lipids, thereby generating diverse damage responses. The electron transfer chain reaction of OXPHOS is the major ROS generation site because it utilizes most of the oxygen, approximately 85–90%, consumed by the cell. The electron transfer reaction is not complete and often leaks electrons in a quinone-mediated radical form. Mitochondrial DNA is highly vulnerable to ROS because it is located in close vicinity to the generation site and it has a naked structure, without stereotypic packing by proteins, like histones. In turn, damaged mtDNA undergoes impaired OXPHOS reactions and releases more ROS in a vicious cycle. Moreover, cells possess plenty of mitochondria. Collectively, this unwanted cycle results in mitochondria that are persistent ROS generators, oxidative stress propagators, and a trigger to initiate or maintain senescent phenotypes, emphasizing its causal role in senescence and the aging process (48–51).

The initial ROS generated from the OXPHOS reaction is superoxide, which is converted to the membrane permeable ROS, H2O2, by mitochondrial manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. Then, the released H2O2 disperses and reacts with various cytosolic and nuclear components, propagating and amplifying oxidative stress signals and damage. Oxidative stress triggers several types of DNA damage, such as oxidized bases, single-strand breaks (SSB), and double-strand breaks (DSB). DSB activates the DDR and induces expression of p53 and its downstream p21, a senescence modulator, through the ATM and ATR kinase cascades (52), leading to staining of γ-H2AX and SAHF senescence markers (Fig. 2). Thus, senescence can be induced by the DSB-mediated DDR, and this is known as telomere-independent premature senescence. Telomeres are susceptible to SSB due to guanine triplet-containing structures, which are extremely sensitive to oxidative modification (53, 54). This implies a potential link between mitochondrial ROS-mediated SSB and telomere attrition, a representative mechanistic driver of replicative senescence. Oxidative stress also modulates telomerase activity, as shown in endothelial (3, 37, 55) and leukemia cells (56). A direct link between mitochondrial dysfunction and telomere attrition was demonstrated using replicative senescence of MRF5 human fibroblasts (57, 58). Together, these observations suggest that mitochondria-initiated oxidative stress can modulate overall telomere maintenance, accelerating telomere attrition.

ANABOLIC DEREGULATION AND RELATED SENESCENT PHENOTYPES

Enlarged cell morphology is the most pronounced phenotype of cell senescence (Fig. 1). This reflects increases in cell mass and components (10), including macromolecules (such as total cellular RNA, proteins, and lipids) and organelles (10, 38, 59), suggesting that the overall cellular components, rather than any specific compartment(s), are augmented in the progress of senescence. As mentioned above, persistent oxidative stress may damage cellular components, and this has been further supported by impaired proteostasis and organelle-homeostasis using an ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy-lysosomal system, respectively (60, 61). However, it is still unclear whether the increase in cell mass and components only results from the accumulation of damaged components. Here, we discuss the importance of anabolic activation, such as glycogenesis, lipogenesis, and protein synthesis, in cell senescence (Fig. 2).

Glycogenesis and cellular granularity

Cellular granularity is the general term for dense particles detected by transmission electron microscopy. Cellular granularity levels can more easily be estimated by the side scatter parameter (SSC), measured with a laser beam (488 nm) that bounces off intracellular particles using flow cytometric analysis. Although the components of the granules are different, depending on the cell type (such as alpha granules in platelets, secretary vesicles in granulocytes, and glycogen granules in muscle and liver), many senescent cells harbor increases in cellular granularity. Therefore, an increase in the SSC has often been used as a marker of cell senescence (24, 59, 62). It is unclear why cell granularity increases and what kinds of granules are formed in the senescence process. An increased number of lysosome-containing lipofuscins is the major component of senescent granules (63); the other components include protein aggregates, such as beta amyloid, and secretory vesicles (64, 65). The accumulation of glycogen aggregates in several cell senescence systems, including replicative senescence of primary human fibroblasts (62), is a new component of senescent granules (Fig. 2). Glycogen granules have also been shown to accumulate in myelinated axons (66) and liver tissues of aged rats (62), and formed inclusion bodies in the cerebral cortex of people over 60 years old (67). The key upstream signaling regulator of glycogenesis is glycogen synthase (GS) kinase 3 (GSK3), which is inactivated by phosphorylation of its upstream kinases, including AKT. Dephosphorylation of GSK3 activates GS activity, enhancing glycogenesis. The GSK3/GS axis modulates senescence (62). Inhibition of GSK3 using siRNA or pharmacological inhibitors induced senescence and enhanced glycogen accumulation, suggesting that glycogenesis is critically involved in senescence. The GS activity can also be negatively regulated by AMPK (68).

The GSK3/GS axis is linked with the insulin-like signaling cascade, IGF1/IR/PI3K/AKT, a key modulator of lifespan and senescence (69–71). This implies that the GSK3/GS-mediated glycogenesis participates primarily in senescence and aging as a major downstream effector of the IGF1 signaling cascade. However, the role of the increased glycogen particles in senescence is not clearly understood. One plausible explanation is that highly aggregated glycogen particles may disrupt the appropriate localization of and/or efficient communication between intracellular organelles because the senescent particles occupy most of the cytoplasmic space, further generating senescent stress. The role of the glycogen particle as the stored form of efficient energy in senescence needs to be clarified.

Lipogenesis and an increase in cellular organelles

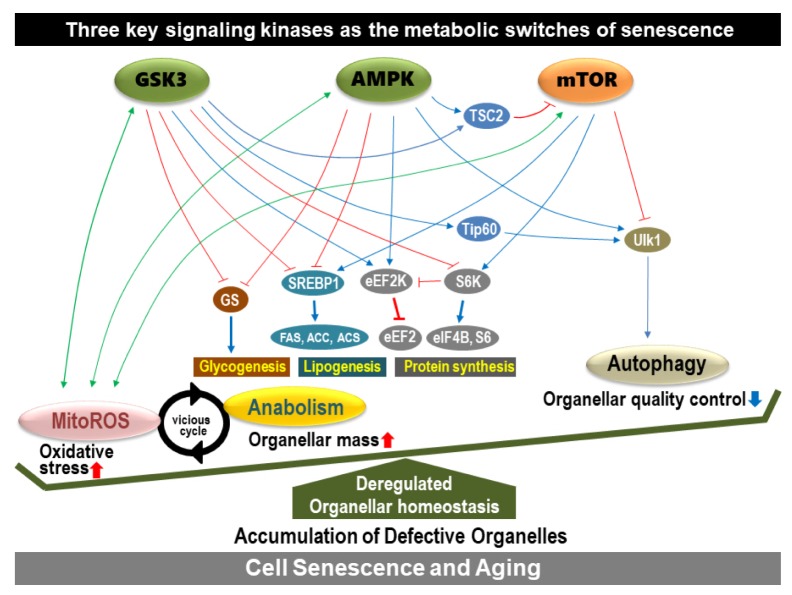

Senescent increases in cell mass and components are reflected in increased cellular organelles, especially membranous ones, such as lysosomes, mitochondria, ER, plasma membrane, etc. The generation of membranous organelles requires biosynthesis of membranous lipids. Lipid biosynthesis, called lipogenesis, is mainly increased during cell proliferation to provide sufficient subcellular organelles for progenies (72, 73). The multiple sequential steps of lipogenesis are governed by several key enzymes, including ATP citrate lyase (ACL), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) (74). The expression of these enzymes is regulated by the master lipogenic transcription factor, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1). Therefore, SREBP1 activity can be a good indicator of lipogenic status. SREBP1 is involved in cell growth by supplying membrane lipids, and it is highly expressed in actively growing cells (75). As expected, several senescent cells possess high levels of the mature form of SREBP1 and its downstream lipogenic enzymes (FAS, ACC, and ACL). Overexpression is sufficient to induce senescence- associated growth arrest, accompanied by increases in membranous lipids and organelle mass (Fig. 2) (38). Thus, an abnormal balance between lipogenesis and cellular growth may trigger senescence. Several upstream regulators of SREBP1, including GSK3, AMPK, and mTOR, regulate senescence and/or aging (76–79), indicating SREBP1-mediated lipogenesis is involved in senescence and aging; mTOR activates SREBP1, whereas GSK3 and AMPK are negative regulators (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The key signaling kinases acting as metabolic switches to regulate senescence.

Senescent cells may generate organelles as a defensive response to compensate for the declined function of organelles damaged by senescence-associated ROS, but newly synthesized organelles may have oxidative stress that aggravates senescence. How does enhanced lipogenesis due to SREBP1 overexpression trigger senescence in normal cellular conditions? To keep normal organellar function, the organelles require a well-balanced composition of their components, including membrane lipids and proteins. Therefore, enhancement of lipogenesis alone may form lipid-enriched abnormal organelles and trigger senescence. In this context, activation of SREBP1 by the upstream regulators plays a key role in modulating senescence and aging. Enhanced lipogenesis of the senescent cells does not only regulate organellar mass, but also increases lipid droplets within a cell (Fig. 2), which may be linked with age-related fat redistribution (80) and hepatic fat accumulation (steatosis). This was supported by recent findings showing that elimination of senescent cells by genetically targeting p16INK4A or by using senolytic drugs, such as dasatinib and quercetin, reduced overall hepatic steatosis (7).

Protein synthesis and dysregulated proteostasis

One of the most important alterations during normal aging is impaired proteasis (protein homeostasis) (81, 82). Cellular maintenance of proteome integrity is governed by a well-balanced control of chaperone-mediated folding and proteasome- and autophagy-mediated degradation systems. Therefore, the senescent impairment of proteasomal and autophagic activities leads to damaged and aggregated proteins. However, the key metabolic regulators, GSK3, AMPK, and mTOR, modulate both protein degradation and protein synthesis. The negative regulator of autophagy, mTOR, activates translation machinery by activating eIF4E, eIF4B, and eEF2, and regulates senescence (83–85). AMPK inhibits protein translation either through inhibiting mTOR or eEF2 (86), and activates autophagy through ULK phosphorylation (87). GSK3 also negatively regulates protein synthesis by phosphorylating eIF2B (88), and activates autophagy via the TIP60/ULK axis (89). Thus, dysregulated proteasis is not only impaired by protein degradation, but also by abnormally enhanced protein synthesis (Fig. 2) (90), emphasizing the three regulators of proteasis and senescence.

DEREGULATED HOMEOSTASIS OF CELLULAR ORGANELLES IN CELLULAR SENESCENCE

Human cells undergo three types of autophagy; microautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), and macroautophagy. Macroautophagy and CMA activities are often decreased with age (91, 92). CMA plays a role in the homeostasis of proteome functionality and macroautophagy in organelle quality control. Although cellular organelles are damaged by oxidative stress derived from mitochondrial dysfunction, macroautophagy can remove the damaged organelles, and enhanced autophagy can generate de novo organelles to maintain homeostasis. However, these activities do not seem to be turned on sequentially or properly, deregulating the organelle homeostasis and leading to defective organelles (Fig. 3). For example, H2O2, a secondary messenger of mitochondrial dysfunction, can phosphorylate (inactivate) GSK3. The phosphorylated GSK3 activates anabolism via SREBP1-mediated lipogenesis, eIF2Bɛ-mediated translation, and GS-mediated glycogenesis (93). Simultaneously, the inactivated GSK3 inhibits autophagy through the TIP60/ULK axis (89). Newly generated organelles, via enhanced anabolism, are immediately placed under oxidative stress and are susceptible to damage, resulting in defective organelles. This phenomenon is further aggravated by defective autophagic activity. Moreover, GSK3 inactivation can cause mitochondrial OXPHOS dysfunction and increase ROS by inhibiting complex IV activity (25). This implies that senescent anabolic activation and mitochondria-derived oxidative stress are closely interconnected in a vicious cycle (Fig. 3). Analogous to GSK3, mTORC1 and AMPK crosstalk with mitochondria via ROS generation (78, 94, 95).

Well-controlled organelle homeostasis is essential for maintaining normal cellular function. In senescence, a mitochondrial defect or abnormal anabolic activation may be the key event that triggers oxidative stress and organelle biogenesis, resulting in a defective increase in organelle mass. In addition, defective autophagy may aggravate this deregulated homeostasis of organelles through loss of its quality control capacity (Fig. 3). Among the three key signaling kinases, AMPK and GSK3 play key roles as positive regulators, while mTOR acts as a negative regulator of the senescent metabolic features.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2012R1A5A2048183).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz-Espin D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–496. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:436–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanks S, Coleman K, Reid S, et al. Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition caused by biallelic mutations in BUB1B. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1159–1161. doi: 10.1038/ng1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, et al. Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016;530:184–189. doi: 10.1038/nature16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat R, Crowe EP, Bitto A, et al. Astrocyte senescence as a component of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogrodnik M, Miwa S, Tchkonia T, et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15691. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafer MJ, White TA, Iijima K, et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byun HO, Lee YK, Kim JM, Yoon G. From cell senescence to age-related diseases: differential mechanisms of action of senescence-associated secretory phenotypes. BMB Rep. 2015;48:549–558. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.10.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang ES, Yoon G, Kang HT. A comparative analysis of the cell biology of senescence and aging. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2503–2524. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0034-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumura T, Zerrudo Z, Hayflick L. Senescent human diploid cells in culture: survival, DNA synthesis and morphology. J Gerontol. 1979;34:328–334. doi: 10.1093/geronj/34.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boffoli D, Scacco SC, Vergari R, Solarino G, Santacroce G, Papa S. Decline with age of the respiratory chain activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1226:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii N, Fujii M, Hartman PS, et al. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394:694–697. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan KJ, Greaves LC, Reeve AK, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:227–240. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson NG. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in mammalian aging. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-093701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lezza AM, Boffoli D, Scacco S, Cantatore P, Gadaleta MN. Correlation between mitochondrial DNA 4977-bp deletion and respiratory chain enzyme activities in aging human skeletal muscles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:772–779. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miquel J, Economos AC, Fleming J, Johnson JE., Jr Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp Gerontol. 1980;15:575–591. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SY, Choi B, Cheon H, et al. Cellular aging of mitochondrial DNA-depleted cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1399–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon G, Kim HJ, Yoon YS, Cho H, Lim IK, Lee JH. Iron chelation-induced senescence-like growth arrest in hepatocyte cell lines: association of transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-beta1)-mediated p27Kip1 expression. Biochem J. 2002;366:613–621. doi: 10.1042/bj20011445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon YS, Byun HO, Cho H, Kim BK, Yoon G. Complex II defect via down-regulation of iron-sulfur subunit induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cell cycle delay in iron chelation-induced senescence-associated growth arrest. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51577–51586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byun HO, Jung HJ, Kim MJ, Yoon G. PKCdelta phosphorylation is an upstream event of GSK3 inactivation-mediated ROS generation in TGF-beta1-induced senescence. Free Radic Res. 2014;48:1100–1108. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.929120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon YS, Lee JH, Hwang SC, Choi KS, Yoon G. TGF beta1 induces prolonged mitochondrial ROS generation through decreased complex IV activity with senescent arrest in Mv1Lu cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:1895–1903. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byun HO, Jung HJ, Seo YH, et al. GSK3 inactivation is involved in mitochondrial complex IV defect in transforming growth factor (TGF) beta1-induced senescence. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1808–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lafargue A, Degorre C, Corre I, et al. Ionizing radiation induces long-term senescence in endothelial cells through mitochondrial respiratory complex II dysfunction and superoxide generation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;108:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu WB, Menon R, Xu YY, et al. Downregulation of peroxiredoxin-3 by hydrophobic bile acid induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence in human trophoblasts. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38946. doi: 10.1038/srep38946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakoshi M, Osamura Y, Watanabe K. Mitochondrial alterations in aged rat adrenal cortical cells. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 1985;10:531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Studies on giant mitochondria. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;488:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb46548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon YS, Yoon DS, Lim IK, et al. Formation of elongated giant mitochondria in DFO-induced cellular senescence: involvement of enhanced fusion process through modulation of Fis1. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:468–480. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westermann B. Merging mitochondria matters: cellular role and molecular machinery of mitochondrial fusion. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:527–531. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skulachev VP. Mitochondrial filaments and clusters as intracellular power-transmitting cables. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:23–29. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ono T, Isobe K, Nakada K, Hayashi JI. Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nat Genet. 2001;28:272–275. doi: 10.1038/90116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai D, Inoue K, Goto Y, Nonaka I, Hayashi JI. The interorganellar interaction between distinct human mitochondria with deletion mutant mtDNA from a patient with mitochondrial disease and with HeLa mtDNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6028–6033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.6028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song M, Franco A, Fleischer JA, Zhang L, Dorn GW., 2nd Abrogating Mitochondrial Dynamics in Mouse Hearts Accelerates Mitochondrial Senescence. Cell Metab. 2017;26:872–883 e875. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide enhances mitochondria quality through autophagy activation in human cells. Aging Cell. 2009;8:426–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurz T, Terman A, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. Lysosomes and oxidative stress in aging and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:1291–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YM, Shin HT, Seo YH, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1-mediated lipogenesis is involved in cell senescence. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29069–29077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.120386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ballinger SW. Beyond retrograde and anterograde signalling: mitochondrial-nuclear interactions as a means for evolutionary adaptation and contemporary disease susceptibility. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:111–117. doi: 10.1042/BST20120227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones AW, Yao Z, Vicencio JM, Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Szabadkai G. PGC-1 family coactivators and cell fate: roles in cancer, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and retrograde mitochondria-nucleus signalling. Mitochondrion. 2012;12:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poyton RO, McEwen JE. Crosstalk between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:563–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finley LW, Haigis MC. The coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial communication during aging and calorie restriction. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8:173–188. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biswas G, Adebanjo OA, Freedman BD, et al. Retrograde Ca2+ signaling in C2C12 skeletal myocytes in response to mitochondrial genetic and metabolic stress: a novel mode of inter-organelle crosstalk. EMBO J. 1999;18:522–533. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butow RA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol Cell. 2004;14:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chae S, Ahn BY, Byun K, et al. A systems approach for decoding mitochondrial retrograde signaling pathways. Sci Signal. 2013;6:rs4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jazwinski SM, Kriete A. The yeast retrograde response as a model of intracellular signaling of mitochondrial dysfunction. Front Physiol. 2012;3:139. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HC, Wei YH. Mitochondrial alterations, cellular response to oxidative stress and defective degradation of proteins in aging. Biogerontology. 2001;2:231–244. doi: 10.1023/A:1013270512172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raha S, Robinson BH. Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:502–508. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sohal RS, Ku HH, Agarwal S, Forster MJ, Lal H. Oxidative damage, mitochondrial oxidant generation and antioxidant defenses during aging and in response to food restriction in the mouse. Mech Ageing Dev. 1994;74:121–133. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)90104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henle ES, Han Z, Tang N, Rai P, Luo Y, Linn S. Sequence-specific DNA cleavage by Fe2+-mediated fenton reactions has possible biological implications. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:962–971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oikawa S, Tada-Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at the GGG sequence by UVA involves acceleration of telomere shortening. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4763–4768. doi: 10.1021/bi002721g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furumoto K, Inoue E, Nagao N, Hiyama E, Miwa N. Age-dependent telomere shortening is slowed down by enrichment of intracellular vitamin C via suppression of oxidative stress. Life Sci. 1998;63:935–948. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pizzimenti S, Briatore F, Laurora S, et al. 4-Hydroxynonenal inhibits telomerase activity and hTERT expression in human leukemic cell lines. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passos JF, Saretzki G, Ahmed S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction accounts for the stochastic heterogeneity in telomere-dependent senescence. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Zglinicki T, Petrie J, Kirkwood TB. Telomere-driven replicative senescence is a stress response. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:229–230. doi: 10.1038/nbt0303-229b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim YM, Byun HO, Jee BA, et al. Implications of time-series gene expression profiles of replicative senescence. Aging Cell. 2013;12:622–634. doi: 10.1111/acel.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korovila I, Hugo M, Castro JP, et al. Proteostasis, oxidative stress and aging. Redox Biol. 2017;13:550–567. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seo YH, Jung HJ, Shin HT, et al. Enhanced glycogenesis is involved in cellular senescence via GSK3/GS modulation. Aging Cell. 2008;7:894–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurz DJ, Decary S, Hong Y, Erusalimsky JD. Senescence-associated (beta)-galactosidase reflects an increase in lysosomal mass during replicative ageing of human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 20):3613–3622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urbanelli L, Buratta S, Sagini K, Tancini B, Emiliani C. Extracellular Vesicles as New Players in Cellular Senescence. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17091408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, Zhao L, Wu Z, Chen X, Ma T. Galantamine alleviates senescence of U87 cells induced by beta-amyloid through decreasing ROS production. Neurosci Lett. 2017;653:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore SA, Peterson RG, Felten DL, O’Connor BL. Glycogen accumulation in tibial nerves of experimentally diabetic and aging control rats. J Neurol Sci. 1981;52:289–303. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(81)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gertz HJ, Cervos-Navarro J, Frydl V, Schultz F. Glycogen accumulation of the aging human brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 1985;31:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spasic MR, Callaerts P, Norga KK. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) molecular crossroad for metabolic control and survival of neurons. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:309–316. doi: 10.1177/1073858408327805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holzenberger M, Dupont J, Ducos B, et al. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature. 2003;421:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyauchi H, Minamino T, Tateno K, Kunieda T, Toko H, Komuro I. Akt negatively regulates the in vitro lifespan of human endothelial cells via a p53/p21-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 2004;23:212–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Demoulin JB, Ericsson J, Kallin A, Rorsman C, Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates membrane lipid synthesis through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35392–35402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Lewis C, Griffiths B, Schulze A. A new player in the orchestra of cell growth: SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to the regulation of cell and organ size. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:278–283. doi: 10.1042/BST0370278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, et al. Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12027–12032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534923100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shimomura I, Shimano H, Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Differential expression of exons 1a and 1c in mRNAs for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 in human and mouse organs and cultured cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:838–845. doi: 10.1172/JCI119247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burkewitz K, Zhang Y, Mair WB. AMPK at the nexus of energetics and aging. Cell Metab. 2014;20:10–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim YM, Song I, Seo YH, Yoon G. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Inactivation Induces Cell Senescence through Sterol Regulatory Element Binding Protein 1-Mediated Lipogenesis in Chang Cells. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2013;28:297–308. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nacarelli T, Azar A, Sell C. Aberrant mTOR activation in senescence and aging: A mitochondrial stress response? Exp Gerontol. 2015;68:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu S, Cai Y, Wei Y. mTOR Signaling from Cellular Senescence to Organismal Aging. Aging Dis. 2014;5:263–273. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.0500263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuk JL, Saunders TJ, Davidson LE, Ross R. Age-related changes in total and regional fat distribution. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:435–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Madeo F, Zimmermann A, Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. Essential role for autophagy in life span extension. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:85–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI73946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV, Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1888–1895. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huo Y, Iadevaia V, Proud CG. Differing effects of rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors on protein synthesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:446–450. doi: 10.1042/BST0390446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Serrano M. Dissecting the role of mTOR complexes in cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2231–2232. doi: 10.4161/cc.21065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fay JR, Steele V, Crowell JA. Energy homeostasis and cancer prevention: the AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:301–309. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wirth M, Joachim J, Tooze SA. Autophagosome formation--the role of ULK1 and Beclin1-PI3KC3 complexes in setting the stage. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maurer U, Preiss F, Brauns-Schubert P, Schlicher L, Charvet C. GSK-3 - at the crossroads of cell death and survival. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1369–1378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li TY, Lin SY, Lin SC. Mechanism and physiological significance of growth factor-related autophagy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2013;28:423–431. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00023.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mazucanti CH, Cabral-Costa JV, Vasconcelos AR, Andreotti DZ, Scavone C, Kawamoto EM. Longevity Pathways (mTOR, SIRT, Insulin/IGF-1) as Key Modulatory Targets on Aging and Neurodegeneration. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:2116–2138. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150610125715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cuervo AM. Autophagy and aging: keeping that old broom working. Trends Genet. 2008;24:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cuervo AM, Wong E. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in disease and aging. Cell Res. 2014;24:92–104. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim YM, Seo YH, Park CB, Yoon SH, Yoon G. Roles of GSK3 in metabolic shift toward abnormal anabolism in cell senescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1201:65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nacarelli T, Azar A, Sell C. Mitochondrial stress induces cellular senescence in an mTORC1-dependent manner. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;95:133–154. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Emerling BM, Weinberg F, Snyder C, et al. Hypoxic activation of AMPK is dependent on mitochondrial ROS but independent of an increase in AMP/ATP ratio. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1386–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]