Abstract

Objectives

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) and chronic neck pain (CNP) are the most common types of chronic pain and chiropractic spinal manipulation is a common nonpharmacologic treatment. This study presents the characteristics of a large US sample of chiropractic patients with CLBP and CNP.

Methods

We collected data from chiropractic patients using multistage systematic stratified sampling with four sampling levels: regions/states, sites (i.e., metropolitan areas), providers/clinics, and patients. The sites and regions were: San Diego, California; Tampa, Florida; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Seneca Falls/Upstate, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Dallas, Texas. Data were collected from patients through an iPad-based prescreening questionnaire in the clinic and emailed links to full screening and baseline online questionnaires. The goal was 20 provider/clinics and 7 patients with CLBP and 7 with CNP from each clinic.

Results

We had 6342 patients at 125 clinics complete the prescreening questionnaire, 3333 patients start the full screening questionnaire, and 2024 eligible patients complete the baseline questionnaire: 518 with CLBP only, 347 with CNP only, and 1159 with both. In general, most of this sample were highly-educated, non-Hispanic white females with at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic, and who have been in pain and using chiropractic care for years. Over 90% report high satisfaction with their care, few use narcotics, and avoiding surgery was the most important reason they chose chiropractic care.

Conclusions

Given the prevalence of CLBP and CNP, the need to find effective nonpharmacologic alternatives for chronic pain, and the satisfaction these patients find with their care, further study of these patients is worthwhile.

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) and chronic neck pain (CNP) are the most common types of chronic pain.1,2 Their combined prevalence is estimated to be about 10 to 20 percent of the adult population.1,3–10 Although there are many treatments for chronic pain,2,11 due to the dangers of opioid abuse, recent efforts have focused on finding effective nonpharmacologic therapies.12 Chiropractors, osteopaths, and physical therapists are the provider types most likely to deliver spinal manipulation,13 one of the nonpharmacologic treatments recommended for these conditions.14–18 In the US about 30 percent of those with spinal pain have used chiropractic.19

However, what is unknown is how those with CLBP and CNP are using chiropractic. Are they using short courses of chiropractic care or are they using this care long term? What are their motivations for using chiropractic care and are they satisfied with this care? Several studies have described the characteristics of typical chiropractic patients,13,20–24 and others have described the characteristics of patients with back or neck pain,6–10,25 including some that focus on chronic forms of these conditions.5,26,27 However, no study provides a detailed look at the demographics, attitudes, motivations, pain and functioning, and the utilization of chiropractic, self-care and other healthcare among those using chiropractic care for their CLBP and CNP. Given the prevalence and long-term nature of chronic pain, understanding these issues population is essential to developing successful policies for the treatment of CLBP and CNP.

This study describes the characteristics of a large US sample of CLBP and CNP patients who use chiropractic care for their chronic low back and neck pain. These data were collected in support of a larger project to advance methods to determine the appropriateness of manipulation and mobilization for CLBP and CNP[ref-paper presently under review].

Methods

This study uses data collected from a national sample of US chiropractic patients with CLBP and CNP.

We used Multistage Systematic Stratified Sampling with four levels of sampling: regions/states, sites (i.e., metropolitan areas), providers/clinics, and patients. We recruited chiropractic practices in large metropolitan areas in six states chosen to represent the major geographical regions of the US and to offer a variety of state laws and regulations related to chiropractic care: San Diego, California; Tampa, Florida; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Seneca Falls/Upstate, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Dallas, Texas.

Our goal was to recruit at least 20 chiropractic providers/clinics per site with our chiropractor sample selected to reflect US national proportions of provider gender, years of experience and patient load as shown in the 2015 Practice Analysis Report from the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners.28 Specifically, our goal for each site was to recruit 30 percent female practitioners; 30 percent with 5–15 years of experience and the rest with more (those with less than 5 years’ experience were excluded as potentially not having sufficient patient load); and equal proportions of those treating between 25 and 74 patients per week and those treating 75 or more patients per week. We also attempted to recruit providers who graduated from a variety of colleges and excluded providers where more than half their patients have open personal injury/workers compensation litigation, and providers who do not use manual manipulation or mobilization (i.e., instrument-assisted-only practice) because these therapies are overwhelmingly used by chiropractors for back and neck pain.13,21,23.

Our aim was to recruit 7 CLBP and 7 CNP cases per clinic to obtain a total of 800 CLBP and 800 CNP study participants. In addition to posters and fliers notifying patients about the study, the front desk staff at each clinic was asked to make a short iPad-based prescreening questionnaire available to every patient who visited the clinic during a 4-week period and to keep a daily tally of all patients seen by participating chiropractors. This prescreening questionnaire was used to determine if patients met the study inclusion/exclusion criteria: at least 21 years of age; could speak English well enough to complete the remaining questionnaires; not presently involved in ongoing personal injury/workers compensation litigation; and have now or ever had low back or neck pain. Patients who met these criteria were invited to be in the study, and if they agreed, they were asked to provide their email addresses and a phone numbers. All patients who provided email addresses received an electronically-delivered $5 gift card.

Patients invited to the study were emailed a longer screening questionnaire to determine whether they met the criteria for CLBP and CNP (i.e., reported pain for at least 3 months prior to seeing the chiropractor and/or stated that their pain was chronic). If they were eligible for the study, patients were then consented for it and asked additional questions. Those not eligible and those who were eligible and started this screening questionnaire but did not finish it received a $5 gift card. Those eligible who consented and went on to complete the remaining questions on this survey received a $20 gift card and were then invited to complete a series of seven online questionnaires (baseline, five shorter bi-weekly follow-ups and end line) over 3 months. Participants received a $25 gift card for completing the baseline questionnaire and could receive a total of $200 in incentives for completing all questionnaires in the study.

The survey instruments were developed using a series of focus groups, exploratory interviews, cognitive interviews, and two pilot studies. Extensive literature searches were used to identify items and instruments for consideration. The evidence from our first pilot test of substantial participant dropout at the point of the longer screening questionnaire (originally fielded as a telephone interview) resulted in our move to complete online delivery of all surveys, a decision which was validated by the results of our second pilot test. Copies of the survey instruments are available upon request.

We report descriptive statistics from the screening and baseline questionnaires. Means and standard deviations are provided for continuous variables and counts and frequencies are provided for categorical variables. In general, pain-related questions asked specifically about someone’s CLBP or CNP. When someone had both CLBP and CNP some of these questions were only asked for the type of pain the respondent rated as worse—i.e., average LBP or NP over the past 6 months, years with pain, and questions about what was important to their decision to use chiropractic. In other cases, those with both CLBP and CNP were asked the question twice—once for CLBP and once for CNP—i.e., Oswestry and Neck disability indexes, years seeing a chiropractor or this chiropractor for pain, total visits and visits in the past 6 months with this chiropractor, and seeing another provider prior to chiropractic or currently and level of improvement. When this group was asked these questions twice the tables report the highest response. Note that questions about respondents’ use of meditation, psychological counseling, exercise, injections, over-the-counter pain medications, herbs/supplements, prescription pain medications, and narcotics did not specify a type of pain and were only asked once of all respondents.

Comparisons between groups use t-tests (continuous data) and chi-squared tests (categorical data). Because our focus is on descriptive analysis, we provide p-values for comparisons across groups, but do not adjust for multiple comparisons.29 The analyses were performed using R 3.4.0. The study was approved by the Human Subject Protection Committee at the ___________.

Results

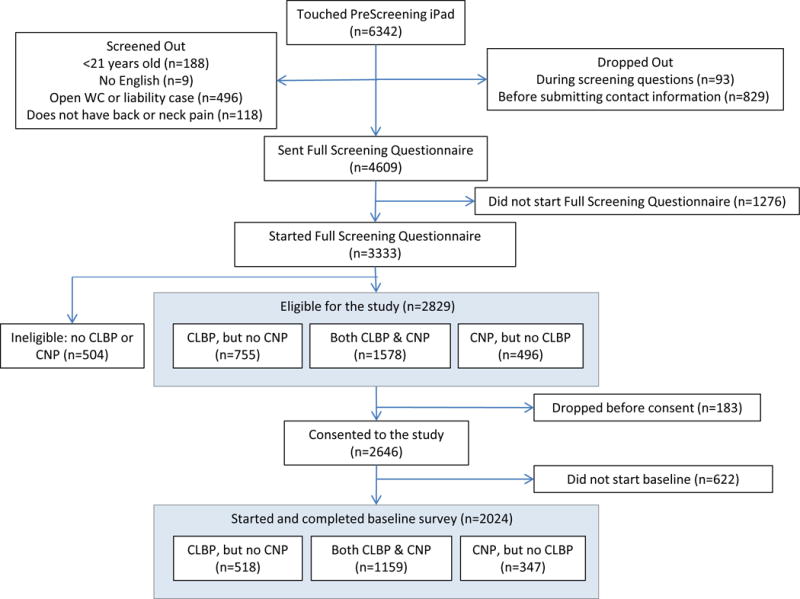

A total of 125 clinics were recruited into the study across the six states: 21 in California, 20 in Florida, 22 in Minnesota, 20 in New York, 21 in Oregon, and 21 in Texas. Data were collected between October 2016 and January 2017. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients into the study. Large numbers of patients were screened out and others drop out as they move through the prescreening and screening questionnaires on their way to the baseline survey.

Figure 1.

Patient flow into the study.

The data we had available before patients screened in and consented to be in the study was limited to location (state). The percent of the sample that drop or screen out between the prescreening survey on the iPad and baseline differs somewhat across states. The clinics in Florida have the lowest percentage of patients that made it to baseline (170 patients or 26.4% of those who completed iPad prescreening in the Florida clinics), whereas the Oregon and Texas clinics have the highest percentages (292 or 34.7% and 414 or 34.6%, respectively). California clinics provided 312 of baseline patients (30.1% of their prescreening sample) and New York clinics provided 336 baseline patients (33.9% of their prescreening sample).

Assuming all clinic patients completed the prescreening questionnaire during patient recruitment, an average of 51 (6342/125) unique patients attended each clinic during that 4-week period. Of course, this is almost certainly an underestimate because it is highly likely that not all clinic patients completed the screener.

About 8% of patients were screened out because they had an open personal injury/workers compensation litigation case, but less than 2% were screened out for reporting that they did not have now, or ever have, back or neck pain. Of those who made it to the full screening questionnaire, 85% (2829/3333) have CLBP or CNP: 23% (755/3333) had only CLBP, 15% (496/3333) had only CNP, and 47% (1578/3333) had both.

Table 1 shows characteristics of the baseline sample based on patient reports. Of those with both CLBP and CNP 611 (52.7%) indicated that their CLBP was worse than their CNP and 548 (47.3%) indicated that their CNP was worse [data not shown]. These chiropractic patients with CLBP and/or CNP were mostly highly-educated, non-Hispanic white women, with at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic, who have been in pain and using chiropractic care for years. The fourth and fifth columns in the table indicate that the patients who dropped out after consenting (the only non-baseline completers for which we have these data) were very similar to those who continued on to baseline. The first three columns show several statistically significant differences between those with CLBP only, both CLBP and CNP, or CNP only. Those with all types of chronic pain were more likely to be female (72%), but the proportion female was especially high for CNP alone (81%) or for both CLBP and CNP (76%). Retired respondents were more prevalent in the CLBP alone (20%) than the CNP alone (12%) groups. Those with both CLBP and CNP reported worse pain and disability, more years with pain and years seeing a chiropractor for pain, and more chiropractic visits than those with either alone. Finally, the proportion of the sample with each type of pain differed by location with those in California and Oregon reporting more CNP alone, and those in New York and Texas reporting more CLBP alone.

Table 1.

Demographic and other characteristics of the baseline sample by type of pain and compared to those who consented but did not go on to the baseline survey

| Completed the baseline surveye

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLBP (n=518) | Both (n=1159) | CNP (n=347) | Total (n=2024) | Dropped (n=444)e | |

| Age - Mean (SD) | 49.3 (15.3) | 48.7 (14.5) | 47.3 (12.8) | 48.6 (14.5) | 49.7 (14.1) |

| Femalea | 303 (58.7%) | 881 (76.1%) | 278 (80.6%) | 1462 (72.4%) | 301 (67.8%) |

| Hispanic or Latinoc | 15 (2.9%) | 59 (5.1%) | 23 (6.7%) | 97 (4.8%) | 24 (5.4%) |

| White | 466 (93.2%) | 994 (90.9%) | 308 (93.3%) | 1768 (91.9%) | 387 (92.8%) |

| Professional degree or Bachelors or abovec,d | 300 (58.0%) | 617 (53.3%) | 208 (60.3%) | 1125 (55.7%) | 218 (49.4%) |

| Working Full Time | 301 (58.8%) | 668 (58.1%) | 221 (63.7%) | 1468 (60.0%) | 278 (63.3%) |

| Working Part Time | 56 (10.9%) | 134 (11.7%) | 45 (13.0%) | 235 (11.7%) | 39 (8.9%) |

| Retiredb | 104 (20.3%) | 185 (16.1%) | 41 (11.8%) | 330 (16.4%) | 78 (17.8%) |

| Gross annual income >$100k | 139 (27.0%) | 330 (28.6%) | 91 (26.2%) | 560 (27.8%) | 119 (26.9%) |

| Some coverage for chiropractic Participants by stateb | 373 (72.0%) | 777 (67.5%) | 234 (68.0%) | 1384 (68.8%) | 292 (65.9%) |

| California | 63 (12.2%) | 186 (16.0%) | 63 (18.2%) | 312 (15.4%) | 66 (14.9%) |

| Florida | 40 (7.7%) | 107 (9.2%) | 23 (6.6%) | 170 (8.4%) | 44 (9.9%) |

| Minnesota | 116 (22.4%) | 300 (25.9%) | 84 (24.2%) | 500 (24.7%) | 103 (23.2%) |

| New York | 111 (21.4%) | 175 (15.1%) | 50 (14.4%) | 336 (16.6%) | 75 (16.9%) |

| Oregon | 68 (13.1%) | 166 (14.3%) | 58 (16.7%) | 292 (14.4%) | 68 (15.3%) |

| Texas | 120 (23.2%) | 225 (19.4%) | 69 (19.9%) | 414 (20.5%) | 88 (19.8%) |

| Mean (SD) Average LBP over past 6 monthsa,f | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.8) | – | 3.1 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.8) |

| Average NP over past 6 monthsa,g | – | 3.2 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.7) | 3.2 (1.8) |

| Oswestry Indexb,f | 19.1 (11.9) | 21.0 (13.1) | – | 20.4 (12.8) | – |

| Neck Disability Indexg | – | 22.9 (13.9) | 21.4 (11.3) | 22.5 (13.4) | – |

| Years with any of these types of paina | 11.3 (11.6) | 15.6 (13.6) | 11.4 (11.8) | 13.8 (13.0) | 14.5 (13.6) |

| Years seeing a chiropractor for paina | 8.9 (10.7) | 12.6 (12.3) | 8 (9.5) | 10.9 (11.6) | 10.6 (11.3) |

| Years seeing this chiropractor for paina | 3.6 (5.4) | 5.1 (7.0) | 3.5 (4.8) | 4.5 (6.3) | 4.7 (7.1) |

| Total visits this chiropractorb | 41.4 (61.9) | 62.3 (116) | 49.3 (101.4) | 54.6 (102.2) | – |

| Visits past 6 months this chiropractora | 10.7 (9.2) | 13.9 (18.8) | 10.5 (9.6) | 12.5 (15.6) | – |

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.001.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.01.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.05.

Values for total baseline were significantly different from values for those who dropped before baseline at p<.05. There were no values for total baseline that were significantly different than for those who dropped before baseline at p<.05.

With the exception of three variables (number of years seeing this chiropractor, years seeing any chiropractor, and total number of visits with rates of missing data between 15% and 27%), the rate of missing data for variables in this table is less than 5%.

These questions were not asked of those with CNP only.

These questions were not asked of those with CLBP only.

Table 2 provides data on how chiropractic care fits into the other healthcare these patients have used for their CLBP and CNP. As can be seen, most chiropractic patients, and especially those with CNP, had seen at least one other type of provider for their CLBP and/or CNP before starting their chiropractic care. The types of practitioners most often used were primary care providers (52%), massage therapists (41%) and physical therapists (28%); patients reported the best results with massage, acupuncture and physical therapy. Less than half of patients had seen another provider in the past 6 months, and a smaller, but still a substantial number (32%), were concurrently seeing another provider. Most patients (67%) reported using exercise often or always for their CLBP and/or CNP, and under half report using over-the-counter medications. About 9% used narcotic medications (opioids) sometimes [data not shown] and another 5% used opioid medications often or always.

Table 2.

Use of other healthcare for CLBP and/or CNP before or during chiropractic care

| Completed the baseline surveyd

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLBP | Both | CNP | Total | |

| (n=518) | (n=1159) | (n=347) | (n=2024) | |

| Saw another provider prior to the chiropractora | 353 (68.1%) | 946 (81.6%) | 245 (70.6%) | 1544 (76.3%) |

| For those who saw another provider, number of different types seena | 1.9 (1.1%) | 2.2 (1.3%) | 1.9 (1.2%) | 2.1 (1.2%) |

| Saw GP or PCP prior to chiropractora | 234 (45.2%) | 663 (57.2%) | 155 (44.7%) | 1052 (52.0%) |

| Improved Little/Lot | 36 (15.4%) | 98 (14.8%) | 18 (11.7%) | 152 (14.5%) |

| Saw physical therapist prior to chiropractora | 120 (23.2%) | 376 (32.4%) | 72 (20.7%) | 568 (28.1%) |

| Improved Little/Lot | 74 (62.2%) | 214 (57.1%) | 44 (61.1%) | 332 (58.7%) |

| Saw orthopedic surgeon prior to chiropractorb | 64 (12.4%) | 160 (13.8%) | 24 (6.9%) | 248 (12.3%) |

| Improved Little/Lot | 15 (23.4%) | 39 (25.2%) | 4 (17.4%) | 58 (24.0%) |

| Saw a Neurologist prior to chiropractora | 22 (4.2%) | 129 (11.1%) | 34 (9.8%) | 185 (9.1%) |

| Improved Little/Lotb | 4 (18.2%) | 31 (24.2%) | 1 (2.9%) | 36 (19.6%) |

| Saw a Massage Therapist prior to chiropractora | 158 (30.5%) | 542 (46.8%) | 138 (39.8%) | 838 (41.4%) |

| Improved Little/Lota | 113 (71.5%) | 462 (85.4%) | 103 (74.6%) | 678 (81.0%) |

| Saw an Acupuncturist prior to chiropractorc | 52 (10.0%) | 168 (14.5%) | 41 (11.8%) | 261 (12.9%) |

| Improved Little/Lot | 28 (53.8%) | 114 (67.9%) | 26 (65.0%) | 168 (64.6%) |

| Saw another provider in past 6 months concurrent with your chiropractora | 199 (38.4%) | 626 (54.0%) | 156 (45.0%) | 981 (48.5%) |

| Currently seeing another providera | 127 (24.5%) | 408 (35.2%) | 110 (31.7%) | 645 (31.9%) |

| Used Meditation or Guided Imagery, Often/Always in past 6 months | 55 (10.7%) | 143 (12.4%) | 50 (14.6%) | 248 (12.3%) |

| Used Psychological Counseling, Often/Always in past 6 monthsc | 14 (2.8%) | 63 (5.6%) | 14 (4.1%) | 91 (4.6%) |

| Used Exercise, Including Yoga, Often/Always in past 6 monthsc | 362 (70.8%) | 733 (63.8%) | 237 (68.9%) | 1332 (66.5%) |

| Got Injections/Shots, Often/Always in past 6 months | 19 (3.7%) | 25 (2.2%) | 5 (1.5%) | 49 (2.4%) |

| Took Over-the-Counter Pain Medications, Often/Always in past 6 months | 227 (44.0%) | 517 (44.7%) | 159 (46.1%) | 903 (44.7%) |

| Took Herbs/Supplements, Often/Always in past 6 monthsa | 75 (14.6%) | 327 (28.3%) | 74 (21.6%) | 476 (23.7%) |

| Took Prescription Pain Medications, Often/Always in past 6 monthsb | 37 (7.2%) | 132 (11.5%) | 24 (7.0%) | 193 (9.6%) |

| Took Narcotics, Often/Always in past 6 months | 26 (5.0%) | 69 (6.0%) | 13 (3.8%) | 108 (5.4%) |

| Ever had Surgeryb | 38 (7.4%) | 72 (6.3%) | 7 (2.0%) | 117 (5.8%) |

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.001.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.01.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.05.

The rates of missing data for all variables in this table is less than 2.5%.

Table 3 provides information about the level of satisfaction and loyalty these chiropractic patients have toward their chiropractors and chiropractic treatment. Almost three-quarters of patients expressed confidence that their chiropractic care would be very/extremely successful in reducing their pain and over 90% reported that they were very/extremely confident in recommending chiropractic to a friend. The two reasons that were most (very/extremely) important to these patients in their decision to use chiropractic for their CLBP and/or CNP were to avoid surgery and trusting that chiropractic was the best option. Other important reasons, all endorsed by between 62% and 78% of respondents, were that it was affordable care, to avoid medications, previous good chiropractic care results, choosing complementary and alternative medicine first, having insurance coverage and convenience. Least important to their decision to use chiropractic was being referred by another provider. As can be seen very few patients with insurance coverage would stop going to their chiropractor (9%) or find someone less expensive (5%) if that coverage ended. In fact, they would be similarly likely to change their insurance provider (10%). Most often they would compensate by having fewer visits (61%).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patient attitudes about and decisions to use chiropractic care

| Completed the baseline survey

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLBP (n=518) |

Both (n=1159) |

CNP (n=347) |

Total (n=2024) |

Dropped (n=444) |

|

| How successful do you think chiropractic will be in reducing your pain - Very or Extremely | 367 (71.3%) |

828 (71.9%) |

262 (75.9%) |

1457 (72.4%) |

– |

| How confident are you in recommending chiropractic to friend - Very or Extremely | 461 (90.0%) |

1079 (93.9%) |

317 (92.7%) |

1857 (92.7%) |

– |

| How important to your decision to use chiropractic for your pain was: | |||||

| Being referred by provider: Very/Extremely Important | 128 (25.5%) |

323 (28.6%) |

85 (25.1%) |

536 (27.2%) |

121 (27.9%) |

| Being referred by friends/family: Very/Extremely Important | 289 (56.9%) |

658 (57.8%) |

199 (58.0%) |

1146 (57.6%) |

232 (53.6%) |

| Getting affordable care: Very/Extremely Important | 391 (76.5%) |

890 (77.9%) |

271 (79.2%) |

1552 (77.8%) |

331 (76.6%) |

| Avoiding surgery: Very/Extremely Important | 421 (82.2%) |

966 (84.9%) |

279 (81.1%) |

1666 (83.6%) |

363 (83.4%) |

| Choosing complementary medicine first: Very/Extremely Importantb | 323 (63.2%) |

818 (71.6%) |

247 (72.4%) |

1388 (69.6%) |

314 (71.9%) |

| Previous good chiropractic results: Very/Extremely Importanta | 349 (68.6%) |

886 (78.2%) |

242 (71.2%) |

1477 (74.5%) |

332 (76.3%) |

| Trusting that chiro is best option: Very/Extremely Important | 412 (80.5%) |

965 (84.1%) |

294 (85.2%) |

1671 (83.3%) |

359 (82.7%) |

| Not getting good results from others: Very/Extremely Important | 301 (59.4%) |

700 (62.0%) |

207 (61.2%) |

1208 (61.2%) |

255 (59.0%) |

| Avoiding medications: Very/Extremely Importantc | 359 (70.1%) |

876 (76.6%) |

266 (77.3%) |

1501 (75.1%) |

321 (73.8%) |

| Convenience: Very/Extremely Important | 310 (60.5%) |

722 (63.1%) |

210 (61.2%) |

1242 (62.1%) |

271 (62.4%) |

| Having insurance: Very/Extremely Important | 326 (63.5%) |

768 (67.2%) |

230 (67.1%) |

1324 (66.2%) |

287 (65.8%) |

| For those with coverage: what would you do if chiropractic was no longer covered | |||||

| Continue as is | 109 (29.2%) |

227 (29.2%) |

68 (29.1%) |

404 (29.2%) |

87 (29.8%) |

| Go less often | 215 (57.6%) |

464 (59.7%) |

139 (59.4%) |

818 (59.1%) |

179 (61.3%) |

| Stop going | 40 (10.7%) |

68 (8.8%) |

19 (8.1%) |

127 (9.2%) |

21 (7.2%) |

| Find less expensive | 23 (6.2%) |

40 (5.1%) |

11 (4.7%) |

74 (5.3%) |

13 (4.5%) |

| Change my insurancec | 33 (8.8%) |

87 (11.2%) |

13 (5.6%) |

133 (9.6%) |

29 (9.9%) |

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.001.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.01.

Values for three pain groups significantly different from each other at p<.05. There were no values for total baseline that were significantly different than for those who dropped before baseline at p<.05.

The rates of missing data for all variables in this table is less than 3%. See Table 1 for the total numbers in each group who had at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic.

Discussion

This study presents the characteristics of a large sample of chiropractic patients with CLBP and/or CNP. In general, most of this sample are highly-educated, non-Hispanic white, females, with at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic and who have been in pain and using chiropractic care for years. These tendencies are generally similar across the different pain subgroups (CLBP-only, CNP-only, or both) with two exceptions. There was a higher prevalence of men in the CLBP-only group than in the other two groups, and the group with both CLBP and CNP tended to have had their pain and used chiropractic care longer.

The best data we have on whether this sample is a true representation of all chiropractic patients at these clinics with CLBP and/or CNP comes from comparing those for whom we have some data (those screened in and who consented to the study, but did not go on to complete baseline) to those who went on to the baseline survey. We found no real statistically significant differences between these groups, even for variables indicating a strong commitment to chiropractic care. We do see differential drop out across states in the numbers that went from the prescreening questionnaire to baseline. However, the interpretation of this finding is unclear.

The study protocol requested that the front desk staff for the clinics in the study give the prescreening questionnaire (on the iPad) to all patients during the 4-week recruitment period and to tally the patients seen by the chiropractors each day. However, clinic staff were inconsistent in taking and reporting this tally, making it difficult to provide an accurate denominator across clinics for our sampling frame. Our best estimate of the average number of unique patients visiting our sample clinics was 51 patients over that 4-week period. But the fact that we lost only 2 percent of the sample for not having back or neck pain is one indication that some of the front desk staff may have only offered the prescreening questionnaire to those they knew to have back or neck pain. Other studies of chiropractic patients have shown that the majority (60–90%) have back or neck pain.20–23 Also of note, 85% of those who made it to the full screening questionnaire were determined to have chronic low back and/or neck pain. Other studies have shown lower, but still substantial, proportions of chronic pain in those with back and neck pain.5,8,9,25 However, there are many definitions of chronicity,30,31 and our higher percentage could reflect our definition of chronicity and/or a biased offering of the prescreening questionnaire by the front desk staff.

Our sample shows a large overlap between the prevalence of CLBP and CNP. At baseline, just over a quarter had CLBP alone, just over 17% had CNP alone and almost 60% had both. Other studies show the higher prevalence of CLBP than CNP, but none show such a large overlap.5,32 Again, this could be at least partially due to our broad definition of chronicity.

The demographics of our sample are similar to what has been seen in other chiropractic, CLBP and CNP samples. Our sample is of similar age19 if not a few years older on average than seen in other studies of chiropractic20–23 and CLBP/CNP.8,10,26,32 Other studies have found that the prevalence of women in chiropractic care20–23 and with CLBP and/or CNP to be higher than for men.5,10,25–27 Previous studies of chiropractic patients have also seen a high prevalence of non-Hispanic whites,20–22 those with high levels of income22 and education,20,22 and those with at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic.20–22 Similar racial/ethnic profiles, and high income and education, were also found for those who used any type of complementary and alternative medicine for back and neck problems.19 Other studies of CLBP and CNP have also seen long durations of pain, although none quite as long as our averages of 11.3 to 15.6 years.26,27,33,34

Our sample is made up of individuals with CLBP and/or CNP who were receiving chiropractic care currently, and had been receiving it for a long time. Therefore, we would expect their average pain and disability scores to better reflect those of others under chiropractic treatment. A study of manipulative treatment for CLBP had an average 0–10 pain score of 5.95 and an Oswestry score of 29.5 at baseline for the treatment group, and a 2.57 pain score and a 13.7 Oswestry score at 12 months.34 Another study of spinal manipulation for CNP had an average 0–10 pain score of 5.6 and a Neck Disability Index score of 27.9 at baseline for the spinal manipulation group, and a 3.5 pain score and a 19.5 Neck Disability Index score at 12 months.33 Our averages for the CLBP-only group were a pain score of 2.8 and Oswestry of 19.1, and for the CNP-only group were a pain score of 2.8 and a Neck Disability Index of 21.4, which are all, as would be expected, closer to these studies’ post-treatment values than baseline.

Our study found that most patients had seen another type of practitioner before coming to the chiropractor and about half saw another practitioner in the past 6 months. The most common types of practitioners seen were primary care providers, massage therapists and physical therapists. Another study of those with neck and low back pain also found that for those who were seeing a chiropractor the most common other practitioners seen were medical doctors, massage therapists and physical therapists.32 Another study of chiropractic patients reported that 3 percent of patients had surgery for their condition before receiving chiropractic care,20 which is lower than our average of 6%. The use of narcotics in our sample of chiropractic patients (an average of 5% reporting often or always use), however, is substantially lower than the 45–60% use found in a large sample of CLBP patients in North Carolina.26

Finally, our sample’s belief in and high recommendation for their chiropractic care aligns well with the consistent high satisfaction with chiropractic care reported elsewhere.13,20,24,35

This study has several limitations. First, since it was a study of those with CLBP and/or CNP under chiropractic care, and not a study of all those with CLBP and/or CNP, we lack the ability to empirically place this sample within the broader CLBP and CNP populations. Second, we excluded chiropractors with instrument-assisted-only practices. We included chiropractors who used instrument-assisted therapies in their practices if they also offered manipulation and/or mobilization. Third, these survey data suffer from the usual limitations related to self-reported measures. Fourth, these data are not from a random sample of all chiropractic patients with CLBP and/or CNP. We used a combination of systematic stratification to get a representative sample of chiropractors, clustering clinics by geographic region to allow for in-person clinic set up, and convenience sampling of all chiropractic patients in those clinics during the 4-week recruitment window. Therefore, it is a reasonable assumption that this sample is representative of all chiropractic patients with CLBP and CNP seen in practices that are not instrument-assisted-only.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into the characteristics of patients who are successfully managing their CLBP and CNP. Findings of this descriptive study of a large sample of chiropractic patients with CLBP and/or CNP reveal this sample to be similar to those found in other studies of chiropractic patients: highly-educated, non-Hispanic white women with at least partial insurance coverage for chiropractic. These individuals have also been in pain and using chiropractic care for years. Most came to chiropractic after trying other types of care, and just under a third continue to receive other concurrent care for their pain. Prior to chiropractic they saw the best results with massage therapy and acupuncture, and report high levels of belief in the success of chiropractic in reducing their pain. This group has low use of narcotics and other pain medications and most rate avoiding surgery as the most important reason for choosing chiropractic care. Given the prevalence of CLBP and CNP, the need to find effective nonpharmacologic alternatives for chronic pain, and the long-term satisfaction these patients find with their care, further study of these patients and their providers and comparisons with other subgroups with CLBP and CNP, areis worthwhile. In addition, documenting the current role chiropractors are playing in the care and treatment of patients with chronic pain may help position these providers for an expanded role in the future.

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgments

Funding sources

Funded by the NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Grant No: 1U19AT007912-01

All authors report that they were funded by a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health during the study. Drs. Coulter and Herman also report that they had support from the NCMIC Foundation outside of the submitted work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

List all potential conflicts of interest for all authors. Include those listed in the ICMJE form. These include financial, institutional and/or other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest. If there is no conflict of interest state none declared.

Practical Applications of your study

The findings of this study describe a group of patients with two of the most common types of chronic pain (chronic low back pain and chronic neck pain). These patients are very satisfied with their care, use few narcotics, and report that avoiding medications and surgery loom large in their choice of chiropractic care. Study of these results and patients could help improve chronic pain care.

Human Subjects and Animals

The study was approved by the Human Subject Protection Committee at the RAND Corporation.

Clinical Trial Registry

Not a clinical trial, but registered as an observational study on ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03162952

Permission to reprint

No previously published figures or tables

Contributorship

For each author, list initials for how the author contributed to this manuscript.

List author initials for each relevant category. For example, John Frank Smith should be “JFS”

Concept development (provided idea for the research)

PMH, MES, CMR, RDH, LGH, GWR, IDC

Desian (planned the methods to generate the results)

PMH, MK, MES, CMR, RDH, LGH, GWR, IDC

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript)

PMH, GWR, IDC

Data collection/processina (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data)

MK, LGH, GWR, IDC

Analvsis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results)

PMH, MK, MES, CMR, RDH, LGH, GWR, IDC

Literature search (performed the literature search)

PMH, LGH, GWR

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript)

PMH, MK, RDH

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking)

PMH, MK, MES, CMR, RDH, LGH, GWR, IDC

Other (list other specific novel contributions)

Characteristics of chiropractic patients being treated for chronic low back and chronic neck pain

Contributor Information

Patricia M. Herman, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Mallika Kommareddi, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Melony E. Sorbero, RAND Corporation, Pittsburg, PA, USA.

Carolyn M. Rutter, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Ron D. Hays, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Lara G. Hilton, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Gery W. Ryan, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

Ian D. Coulter, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NMX. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Revista de Saude Publica. 2015;49:1–9. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2015049005874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):251–258. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb R, Brammah T, Lunt M, Urwin M, Allison T, Symmons D. Prevalence and predictors of intense, chronic, and disabling neck and back pain in the UK general population. Spine. 2003;28(11):1195–1202. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000067430.49169.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bovim G, Schrader H, Sand T. Neck pain in the general population. Spine. 1994;19(12):1307–1309. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guez M, Hildingsson C, Nilsson M, Toolanen G. The prevalence of neck pain. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 2002;73(4):455–459. doi: 10.1080/00016470216329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassidy JD, Cote P, Carroll LJ, Kristman V. Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population. Spine. 2005;30(24):2817–2823. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000190448.69091.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C. Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(2):149–165. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogg-Johnson S, Van Der Velde G, Carroll LJ, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(1):39–51. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816454c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou R, Atlas SJ, Stanos SP, Rosenquist RW. Nonsurgical Interventional Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline. [Review] Spine. 2009;34(10):1066–1077. 1078–1093. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a103b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Pain Strategy Task Force. National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population Health-Level Strategy for Pain. Bethesda, MD: Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee (IPRCC), National Institutes of Health (NIH); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurwitz EL. Epidemiology: spinal manipulation utilization. J Electromyography Kinesiol. 2012;22(5):648–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):A1–A34. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren Å. The bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:5–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643f40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, et al. Treatment of neck pain: noninvasive interventions: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2):S141–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenger HC, Cifu AS. Treatment of low back pain. JAMA. 2017;318(8):743–744. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin BI, Gerkovich MM, Deyo RA, et al. The association of complementary and alternative medicine use and health care expenditures for back and neck problems. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e0b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coulter ID, Shekelle PG. Chiropractic in North America: a descriptive analysis. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2005;28(2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mootz RD, Cherkin DC, Odegard CE, Eisenberg DM, Barassi JP, Deyo RA. Characteristics of chiropractic practitioners, patients, and encounters in Massachusetts and Arizona. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2005;28(9):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevans JM, Zodet MW. Clinical, demographic, and geographic determinants of variation in chiropractic episodes of care for adults using the 2005–2008 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2012;35(8):589–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurwitz EL, Coulter ID, Adams AH, Genovese BJ, Shekelle PG. Use of chiropractic services from 1985 through 1991 in the United States and Canada. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(5):771–776. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper RA, McKee HJ. Chiropractic in the United States: trends and issues. Milbank Q. 2003;81(1):107–138. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Kristman V. The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Pain. 2004;112(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knauer SR, Freburger JK, Carey TS. Chronic low back pain among older adults: a population-based perspective. J Aging Health. 2010;22(8):1213–1234. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verkerk K, Luijsterburg P, Heymans M, et al. Prognosis and course of pain in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain: A 1-year follow-up cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(8):1101–1110. doi: 10.1002/ejp.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen MG, Hyland JK, Goertz CM, Kollasch MW. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015. Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; Jan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cedraschi C, Robert J, Goerg D, Perrin E, Fischer W, Vischer T. Is chronic non-specific low back pain chronic? Definitions of a problem and problems of a definition. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(442):358–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Korff M, Miglioretti DL. A prognostic approach to defining chronic pain. Pain. 2005;117(3):304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Côté P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The treatment of neck and low back pain: who seeks care? who goes where? Med Care. 2001;39(9):956–967. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans R, Bronfort G, Nelson B, Goldsmith CH. Two-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of spinal manipulation and two types of exercise for patients with chronic neck pain. Spine. 2002;27(21):2383–2389. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemistö L, Lahtinen-Suopanki T, Rissanen P, Lindgren K-A, Sarna S, Hurri H. A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003;28(19):2185–2191. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000085096.62603.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Posner J, Glew C. Neck Pain. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:758–759. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]