Abstract

Physical dating aggression is a prevalent and costly public health concern. A theoretical moderator model of substance use and dating aggression posits that associations between them are moderated by relational risk factors. To test these theoretical expectations, the current study examined seven waves of longitudinal data on a community-based sample of 100 male and 100 female participants in a Western U.S. city (M age Wave 1 = 15.83; 69.5% White non-Hispanic, 12.5% Hispanic, 11.5% African Americans, & 12.5% Hispanics). Multilevel models examined how links between substance use and dating aggression varied by relational risk and how these patterns changed developmentally. Main effects of relational risk and substance use emerged, particularly in adolescence. In young adulthood significant three-way interactions emerged such that substance use was more strongly associated with physical aggression when conflict and jealousy were higher. Thus, relational risk factors are integral to models of dating aggression, but their role changes developmentally.

Keywords: Dating aggression, dating violence, romantic relationships, substance use

Introduction

Physical dating aggression is a prevalent and costly public health concern. Lifetime rates of physical dating aggression involvement range from 28% to 50% (Breiding, Chen, & Black, 2014). Such aggression is associated with poorer health outcomes, physical health risks, and psychological consequences (Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013; Lawrence, Orengo- Aguayo, Langer, & Brock, 2012). Due to the high prevalence rates and the consequences for individuals, understanding the risk factors for the development of dating aggression has been identified as a research priority (Breiding, et al., 2014). The current study addresses this research priority by testing a theoretical model of substance use and dating aggression in adolescence and young adulthood. Victimization and perpetration are highly correlated and most often co-occur during adolescence and young adulthood (O’Leary & Slep, 2003; Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008). Consequently, the current study examined overall physical dating aggression involvement, which includes dating aggression victimization, perpetration, and mutual aggression (Collibee & Furman, 2016; Connolly, Friedlander, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2010; Williams, et al., 2008).

Substance Use and Dating Aggression

Among adults, substance use is an established risk factor for partner violence (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a; Shorey, Rhatigan, Fite, & Stuart, 2011; Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius 2012). More recently, a growing body of research has found similar associations between substance use and physical dating aggression in adolescence and young adulthood (Epstein-Ngo, Cunningham, Whiteside, Chermack, Booth, Zimmerman, & Walton, 2013; Rothman, Reyes, Johnson, & LaValley, 2010). Even though substance use is significantly associated with partner violence, in many instances substance use does not result in such violence (Schumacher, Fals- Stewart, & Leonard, 2003). Further, partner violence can occur in the absence of substance use (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a). Thus, researchers have called for conceptual models that place a greater emphasis on interaction processes and moderators of the links between substance use and partner violence or dating aggression (Capaldi & Kim, 2007; Foran & O’Leary, 2008a).

One such theoretical model that has received increasing attention is a theoretical moderator model (sometimes referred to as a multiple threshold model) (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a; Rothman et al., 2011). A theoretical moderator model of substance use and partner violence posits that the associations between substance use and dating aggression may be moderated by individual and situational/relational risk factors, such that substance use has a greater effect on individuals with higher levels of these other risk factors (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a; Rothman et al., 2011). In contrast, a smaller association between substance use and aggression occurs for those with low levels of other risk factors. Among adults, the patterns hypothesized by a theoretical moderator model have been found in clinical and community samples (Feingold, Washburn, Tiberio, & Capaldi, 2015; Foran & O’Leary, 2008a, 2008b). For example, problem drinking is associated with higher levels of physical aggression for individuals with poor anger control and high levels of jealousy, whereas such drinking is not associated with greater aggression for individuals with good anger control and low levels of jealousy (Foran & O’Leary, 2008b). Theoretically, substance use may lead to hostile communications that escalate into aggression among individuals who have problems controlling their anger or are jealous. In contrast, substance use may have little effect on those with low levels of these risk factors because the disinhibiting effect will not be great enough to escalate into physical aggression.

Despite the growing empirical support for a moderator model among adults, only two studies have assessed moderators of the associations between substance use and dating aggression among adolescents. Specifically, Reyes and colleagues examined the moderating effects of family, peer, and neighborhood violence on the links between heavy alcohol use and dating aggression among adolescents (Reyes, et al., 2012; Reyes, Foshee, Tharp, Ennett, & Bauer, 2015). They found that family and peer violence moderated the associations between alcohol use and dating aggression; further, these moderating effects became increasingly important as adolescents grew older. Thus, some initial work suggests that such models may help account for the associations in adolescence and young adulthood, but more research on other potential moderators is needed to better elucidate the associations between substance use and dating aggression in adolescence.

Relational Risk Factors

A moderator model conceptualization of substance use and dating aggression posits that these links may be moderated by relational risk factors. Such relational risk factors typically are theorized to include conflict, intimacy, and sometimes jealousy (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a; Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). To date, however, most work testing theoretical moderator models of substance use and aggression has focused on individual risk factors in adulthood, such as anger control or individual psychopathology (Foran & O’Leary, 2008b). The limited work that has examined relational risk factors within a moderator model among adults is nonetheless promising, finding the hypothesized patterns (Foran & O’Leary, 2008b).

Relational risk factors may receive less attention in part because they have been relatively understudied more broadly (Giordano, Soto, Manning, & Longmore, 2010). Further, the limited work that has examined the main effects of relational risk factors on dating aggression has relied predominately on cross-sectional studies, and findings have been mixed (Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). Specifically, some cross-sectional studies found that greater intimacy and support seeking is a protective factor for aggression (Marcus & Swett, 2002), but others found them to be a risk factor (Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2005). More recent longitudinal work using the same dataset as the current study demonstrated that increased negative interactions, jealousy, and decreased relationship satisfaction were associated with greater risk for physical aggression. However, it did not examine whether they moderated the influence of substance use (Collibee & Furman, 2016). Despite being understudied, some preliminary evidence suggests they may be more predictive of dating aggression than more commonly studied factors such as anger control (Foran & O’Leary, 2008b) or individual psychopathology (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; White, Merrill, & Koss, 2001). Thus, although they have received less attention than other risk factors, relational risk factors have emerged as important for understanding dating aggression. As such, it is necessary to test the theoretical expectation that these risk factors moderate the associations between substance use and dating aggression among adolescents and young adults. The current study focused on negative interactions, jealousy, and support. Negative interactions reflect patterns of hostile communication and are theorized to increase intensity of conflict, thereby exacerbating the risk of escalation to physical dating aggression (Riggs & O’Leary, 1989). Relatedly, jealousy may increase the risk of such hostile communication. In contrast, support in the relationship includes positive communications and intimacy seeking/providing‥ Thus, lower levels of support were theorized to reflect less positivity in the relationship. which in turn was expected increase the likelihood of escalation to physical dating aggression (Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). Each of these relational risk factors has also been empirically shown to be associated with dating aggression involvement (Kaura & Lohman, 2007; O’Keefe, 2005; O’Leary & Slep, 2003; Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013).

Developmental Changes

As adolescents get older, their relationships become more intimate and more likely to require managing conflict and disagreements. The prevalence of dating aggression increases developmentally as well (Johnson, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2015). Accordingly, theoretical models of dating aggression have suggested that risk for dating aggression may be higher in certain developmental periods (Capaldi, Shortt, & Kim, 2005). Indeed, age is also thought to function as a potential moderator of the links between substance use and aggression (Feingold, et al., 2015; Reyes et al., 2012). As yet, however, no study has examined the pattern of associations in both adolescence and young adulthood.

Finally, the moderating effect of relational risk factors on substance use may also vary developmentally (Capaldi, et al., 2005). That is, because contextual risk factors, such as family and peer relationships, have been shown to emerge more frequently as youth grow older (Reyes et al., 2012), relational risk factors may do the same. Thus, it is important to examine potential three-way interactions among substance use, age, and relational risk factors. Such effects would have important implications for developing interventions, as they would suggest developmental periods of increased risk as well as optimal opportunities to intervene.

Current Study

The current study tested a moderator model of the associations among substance use, relational risk factors, and dating aggression over a nine year period from middle adolescence to young adulthood (15-24 years of age). Each of the three relational risk factors (conflict, jealousy, and support) was assessed using multiple methods (interview & self-report measures). First, it was hypothesized that conflict, jealousy, substance use, and age would all be positively associated with physical dating aggression and support would be negatively associated with physical dating aggression (Hypothesis 1). Consistent with a moderator model, it was hypothesized that substance use would be associated with greater risk for physical dating aggression in the context of higher levels of conflict or jealousy and lower support (Hypothesis 2). To assess this hypothesis, the current study examined whether the interactions between each of the three relational risk factors and substance use were predictive of physical dating aggression. It was expected that these associations would change developmentally, such that the interactions between relational risk factors and substance use would become stronger in young adulthood (i.e., an age by relational risk factor by substance use interaction) (Hypothesis 3). Finally, gender was included in the model to test for possible gender differences in physical dating aggression. However, as prior work has shown largely similar findings across gender no specific gender effects were hypothesized (Brooks-Russell, Foshee, & Reyes, 2015).

Method

Participants

The participants were part of a longitudinal study investigating the role of close relationships on psychosocial adjustment. Two hundred 10th grade high school students (100 men, 100 women; M age = 15 years 10.44 months old, SD = .49) were recruited from a diverse range of schools and neighborhoods in a large Western metropolitan area. Brochures and letters were distributed to families residing in various zip codes and to students enrolled in various schools in ethnically diverse neighborhoods. The ascertainment rate could not be determined because brochures were distributed and letters were sent to many families who did not have a 10th grader. To insure maximal response, families $25 were paid to hear a description of the project in their home. Of the families that heard the description, 85.5% expressed interest and carried through with the Wave 1 assessment.

We selected participants so that the sample would approximate the proportions of individuals from different ethnic and racial groups in the United States; thus, the sample consisted of 11.5% African Americans, 12.5% Hispanics, 1.5% Native Americans, 1% Asian American, 4% biracial, and 69.5% White, non-Hispanics. The sample was of average intelligence, but mother’s average level of education was higher than national norms, suggesting that the sample was predominately middle or upper-middle class.

We also compared the sample’s scores to comparable national norms of representative samples for trait anxiety scores on the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1983), maternal report of externalizing symptoms on the Child Behavior Child Checklist (Achenbach, 1991), participants’ reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms on the Youth Self Report, and 8 indices of substance use from the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2002). The present sample was more likely to have tried marijuana; otherwise the sample scores did not differ significantly from the national scores on the other 11 measures, including frequency of marijuana usage.

Procedure

Adolescents were interviewed about romantic relationships and completed questionnaires. The mother and a close friend nominated by the participant also completed questionnaires at their convenience about the participant’s psychosocial competence and risky/problem behaviors (M mother N = 169, M friend N = 145).

The current study used the first through seventh waves of data collection, beginning when the participants were in the 10th grade and ending approximately 5.5 years after graduation from high school. Each of the measures was collected at every wave. Data were collected on a yearly basis in Waves 1 through 4, and then every one and a half years for Waves 5-7. To maximize retention, efforts were made to contact the participants every 4 months. If the participant had left the area and not returning at some point, research assistants traveled to their current location to conduct the sessions. Additionally, participants, friends, and mothers were all compensated financially for participation; such compensation increased over time. Participant retention was excellent (Wave 1 & 2: N = 200; Wave 3: N = 199, Wave 4: N = 195, Wave 5: N = 186, Wave 6: N = 185, Wave 7: N = 179). In the sample 5.5% got married. These participants were excluded from the data once they were married as the study was only interested in dating aggression, and not partner violence among married couples.

Regarding sexual orientation, 89.3% of participants said they were heterosexual in Wave 7, whereas the remaining 10.7% said they were gay, lesbian, bisexual, or questioning. Sexual minorities were retained in the sample to be inclusive.

The local Institutional Review Board approved the study. A Certificate of Confidentiality issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services protected the confidentiality of the participants’ data.

Measures

Physical dating aggression.

Participants reported on their own use of physical aggression (perpetration) as well as their partner’s use of physical aggression (victimization) using the Conflict Resolution Style Inventory (CRSI; Kurdek, 1994). For all relationship variables, participants were instructed to report on their most important romantic relationship during the past year. Physical aggression was assessed by adapting four items (e.g., “Forcefully pushing or shoving,” “Slapping or hitting,” “Throwing items that could hurt,” and “Kicking, biting or hair pulling” ; M alpha = .90). Based on an involvement model of physical dating aggression (Connolly, Friedlander, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2010; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008), ratings of victimization and perpetration were combined. Correlations between physical victimization and perpetration (M r = .65) supported this conceptualization. Patterns of effects for perpetration and victimization were examined separately and obtained similar results (supplemental results available upon request from the corresponding author).

Relationship support and conflict.

Participants completed the Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version (NRI; Furman & Buhrmester, 2009) to assess their perceptions of their most important romantic relationship in the last year. The short version of the NRI includes five items regarding social support (e.g., “How much do you turn to this person for comfort and support when you are troubled about something?”) and six items regarding negative interactions/conflict (e.g., “How much do you and this person get on each other’s nerves?”). Participants used a 5-point scale to rate how much each description was characteristic of their romantic relationship. Support and negative interaction scores were derived by averaging the relevant items (M α = .89 & M α = .92, respectively).

Jealousy.

Participants completed the Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (MJS; Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989) to assess jealousy within their most important romantic relationship in the last year. Using a five-point Likert scale, participants completed 24 questions assessing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral jealousy. An example of an item is: “I question my boy/girlfriend about his or her whereabouts.” (M alpha = .91). The 24 items were averaged to derive a total score.

Interview Ratings of Support, Conflict, and Involving Behaviors.

The Romantic Interview (RI; Furman, 2001) was used at each wave to assess participants’ interactions with their most important romantic partner in the last year. The RI was based on the Adult Attachment Interview (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1985/1996). Many questions were the same or similar to those of the AAI. For example, participants were asked to describe their romantic relationships using specific memories to support descriptions. They were also asked about separation, rejection, threatening behaviors, and being upset within their romantic relationship.

Most interviews were conducted in the laboratory by trained research assistants. The interview typically took between 45 and 90 minutes. The RIs were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Crowell and Owen’s (1996) Current Relationship Inventory (CRI) coding system was used to rate participants’ support seeking and providing, conflict, participants’ controlling behaviors, and participants’ involving behaviors. The coders were graduate students in clinical or developmental psychology. All coders attended Main and Hesse’s AAI Workshop and received additional training in coding the Romantic Interviews.

Interview rating of support.

Coders rated support seeking and support providing by the participant (Interrrater agreement intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = .72). Support seeking refers to expressing distress, accepting comfort, and using the other as a secure base. Support providing refers to providing support at times of distress and serving as a secure base for one’s romantic partner. The scores of the two scales were averaged to derive a support composite. This composite was conceptualized as analogous to the NRI self-report rating of support, but based on interview data.

Interview rating of conflict.

Coders rated the amount of conflict in the romantic relationship, taking into account its intensity and frequency (Interrater ICC = .78). Interview ratings of conflict were conceptualized as analogous to the self-report of negative interactions, but based on interview data.

Interview rating of involving behaviors.

Coders gave an overall rating of the degree to which the participant engaged in involving behaviors, which are behaviors designed to keep the partner focused on them and the romantic relationship (Interrater ICC = .69). Such involving behaviors limit the partner exploration and autonomy and feelings of confidence. Because involving behaviors also include expressions of sexual jealousy and attempts to make the partner jealous, the rating of involving behavior was conceptualized as analogous to the self-report of jealousy, but based on interview data.

Substance use.

Participants completed the Drug Involvement Scale for Adolescence (Eggert, Herting, & Thompson, 1996), which assessed use of beer, wine, liquor, marijuana, and other drugs (cocaine, opiate, depressants, tranquilizers, hallucinogens, inhalants, stimulants, over-the-counter drugs, & club drugs) over the last 30 days. Frequency of each substance use was scored on a 7-point scale ranging from never to every day. Additionally, they completed a 16 item measure assessing adverse consequences arising from substance use (M α =.94), and an 8 item measure assessing difficulties in controlling substance use (M α =.91). The questionnaires on substance use were administered by computer assisted self-interviewing techniques to increase the candor of responses.

As part of their version of the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988), a friend nominated by the participant was asked five questions about the participant’s use of alcohol and drugs and problems related to the use of those substances. The five items were averaged to derive the friend report of the participant’s substance use and problems (M α =.82). The selfreport an friend report of participant’s substance use were correlated (M r = .49).

Derivation of composites.

First, as the interview and self-report scales of relational risk factors were substantially correlated with one another (M r for support = .44, M r for conflict = .51, M r for jealousy = .39), the corresponding interview and self-report scales were combined into composites for each variable at each wave. All analyses were also conducted to examine self-report and interview separately and obtained similar patterns of effects (supplemental results available upon request from corresponding author). The measures used to create the composites had different numbers of points on their scales, which means the scores are not comparable to one other. Consequently, scale scores were standardized across all waves to render the scales comparable with one another, a recommended procedure that retains differences in means and variance across age, and does not change the shape of the distribution or the associations among the variables (Little, 2013). In other words, all the data across the seven waves were compiled for each measure, and one set of standardized scores for each wave of each individual measure was derived. Standardized scores on the self-report and interview measures were then averaged to form the composite for each variable at each wave.

With regard to substance use, first, scores were standardized on each measure across all waves to render the scales comparable with one another. Next, the participants’ reports of beer or wine drinking and their reports of drinking liquor were averaged to obtain a measure of alcohol use. Similarly, the participants’ reports of marijuana use, and their reports of other drug use was averaged to derive a measure of drug use. The participants’ reports of intra- and interpersonal problems, control problems and adverse consequences of use were each averaged to derive a measure of problem usage. In a final step, the participants’ alcohol, drug, and problem usage, and their friends’ reports of substance use were averaged to derive a composite measure of substance use at each wave.

Analytic Strategy

Our hypotheses regarding a moderator model were assessed through a series of multilevel models (MLMs) using the statistical program MPlus v.8 with robust estimation (MLR) (Muthén & Muthén, 2001). Multiple imputation (MI) procedures were used to estimate missing data (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Relevant auxiliary variables were included in the multiple imputations to maximize the likelihood of meeting the assumption that the data were missing at random (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001). Multiple imputation provides a powerful alternative to listwise deletion and protects against bias in analyses (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007; Little, Jorgensen, Lang, & Moore, 2013). One hundred multiple imputation datasets were generated using the software program Amelia II (Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2011), and the results of the analyses of the 100 datasets were averaged using MPlus in accordance with Rubin’s rules (Rubin, 2004). Those participants who did not have a romantic relationship in a certain wave provided information on other variables of interest, including substance use. Participants who did not have a romantic relationship anytime during the study period were removed (n = 5).

Results

Means and standard deviations of the relevant variables can be found in Table 1. In Wave 1, 59% of participants reported having had a romantic partner in the last year; in Wave 2, 66% had a romantic partner; in Wave 3, 78% had a romantic partner; in Wave 4, 75% had a romantic partner; in Wave 5, 73% had a romantic partner; in Wave 6, 79% had a romantic partner; in Wave 7, 80% had a romantic partner.

Table 1.

Mean Relational Risk Factors and Dating Aggression (with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | Wave 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.88 (0.47) | 16.89 (0.47) | 17.94 (0.50) | 19.03 (0.56) | 20.51 (0.56) | 22.11 (0.51) | 23.70 (0.61) |

| Conflict | −0.09 (.74) | −0.09 (.86) | 0.13 (1.10) | −0.10 (.92) | 0.11 (.94) | 0.05 (.91) | 0.02 (.79) |

| Jealousy | −0.02 (.82) | −0.08 (.87) | 0.07 (88) | −0.06 (.88) | 0.05 (.89) | −0.07 (.81) | −0.09 (.80) |

| Support | −0.19 (.83) | 0.08 (.90) | 0.06 (.82) | −0.03 (.84) | 0.08 (.84) | 0.20 (.84) | 0.28 (.83) |

| Physical Aggression | 1.14 (0.33) | 1.14 (0.38) | 1.25 (0.53) | 1.18 (0.37) | 1.14 (0.33) | 1.12 (0.32) | 1.12 (0.36) |

First, the hypothesized three-way interactions were tested using the following model.

Table 2 presents these results:

Level 1: Yi = β0 + β1(age) + β2(substance use) + β2(relational risk factor) + β3(age x substance use) + β4 (relational risk factor x substance use) + β5(age x relational risk factor) + β6(age x relational risk factor x substance use) + ri

- Level 2:

- β0 = γ00 + γ01(gender) + u0

- β1 = γ10

- β2 = γ20

- β3 = γ30

- β4 = γ40

- β5 = γ50

- β6 = γ60

Table 2.

Multilevel Models Testing the Associations between Relational Risk Factors and Aggression

| Physical Aggression Involvement |

|

|---|---|

| Conflict | |

| Intercept (β0) | 1.24 (.08) |

| Age (β1) | −0.01 (.00) [−.11] * |

| Substance use (β2) | 0.05 (.02) [.07] * |

| Conflict (β3) | 0.14 (.02) [.35] *** |

| Age X Substance Use (β4) | −0.02 (.01) [.04] * |

| Conflict X Substance Use (β5) | 0.06 (.03) [.09] * |

| Conflict X Age (β6) | −0.01 (.01) [−.01] |

| Conflict X Age X Substance use (β7) | 0.02 (.01) [.09] ** |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | −0.05 (.04) [−.18] |

| Jealousy | |

| Intercept (β0) | 1.27 (.08) |

| Age (β1) | −0.01 (.01) [−.08] * |

| Substance Use (β2) | 0.06 (.02) [.09] * |

| Jealousy (β3) | 0.05 (.02) [.12] * |

| Age X Substance Use (β4) | −0.01 (.01) [−.03] |

| Jealousy X Substance Use (β5) | 0.06 (.03) [.09] * |

| Jealousy X Age (β6) | 0.01 (.01) [.00] |

| Jealousy X Age X Substance Use (β7) | 0.02 (.01) [.08] * |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | −0.07 (.04) [−.21]† |

| Support | |

| Intercept (β0) | 1.23 (.08) |

| Age (β1) | −0.01 (.01) [−.06] † |

| Substance use (β2) | 0.06 (.02) [.10] * |

| Support (β3) | −0.03 (.02) [.10] * |

| Age X Substance Use (β4) | −0.00 (.01) [−.14] |

| Support X Substance Use (β5) | −0.02 (.03) [−.02] |

| Support X Age (β6) | −0.01 (.01) [−.03] |

| Support X Age X Substance Use (β7) | 0.00 (.01) [−.01] |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | −0.04 (.04) [−.14] |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects. Standard errors are in parentheses. Standardized coefficients are in brackets.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

We examined the interaction effects after the main effects to avoid concerns of conditionality (Little, 2013). In instances of significant three-way interactions with age (β6), the results indicated that the interaction between relational risk factors and substance use varied developmentally. To better understand these developmental differences, two-way interactions between the relational risk factor and substance use for adolescents (Waves 1-3) and young adults (Waves 4-7) were examined separately. To do this, the data were split by adolescence or young adulthood, and examined the following model for each developmental period:

Level 1: Yi = β0 + β1(age) + β2(substance use) + β2(relational risk factor) + β4(relational risk factor x substance use) + ri

- Level 2:

- β0 = γ00 + γ01(gender) + u0

- Β1 = γ10

- β2 = γ20

- β3 = γ30

- β4 = γ40

These steps allowed for a test of the potential developmental changes in the moderator model.

Table 3 presents these results.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models Testing two-way Interactions between Substance Use and Relational Risk Factors in Adolescence and Young Adulthood for Physical Aggression Involvement

| Adolescence (Waves 1–3) |

Young Adulthood (Waves 4–7) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Conflict | ||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.32 (.06) | 1.21 (.08) |

| Age (β1) | −0.00 (.02) [−.00] | −0.01 (.02) [−.01] |

| Substance use (β2) | 0.06 (.04) [.09] * | 0.03 (.03) [.03] |

| Conflict (β3) | 0.16 (.03) [.29] *** | 0.14 (.02) [.14] *** |

| Conflict X Substance Use (β5) | 0.06 (.04) [.04] | 0.07 (.03) [.12]* |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | 0.04 (.04) [−.23] | −0.04 (.04) [−.13] |

| Jealousy | ||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.33 (.06) | 1.24 (.08) |

| Age (β1) | 0.01 (.02) [.02] | −0.01 (.01) [−.05] |

| Substance Use (β2) | 0.07 (.03) [.10] * | 0.04 (.03) [.08] |

| Jealousy (β3) | 0.04 (.02) [.09] † | 0.06 (.02) [.17] ** |

| Jealousy X Substance Use (β5) | 0.05 (.04) [.07] | 0.07 (.03) [.11]* |

| Gender Main Effect (γ01) | −0.06 (.04) [−.24] | −0.02 (.04) [−.18] |

Notes. The primary numbers in the table are the unstandardized coefficients for the fixed effects. Standard errors are in parentheses. Standardized coefficients are in brackets.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

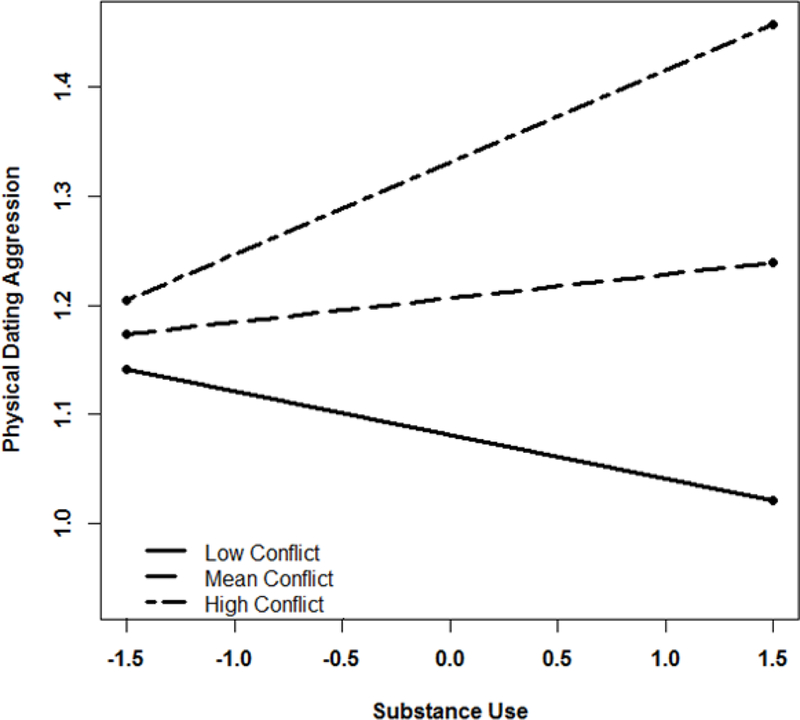

Conflict

A significant three-way interaction emerged among age, substance use, and conflict in association with physical dating aggression involvement, which qualified the significant main effects and interactions presented in Table 2. Therefore, the effects of substance use and conflict were examined separately in adolescence and young adulthood (see Table 3).

In adolescence, a main effect of conflict was found for physical aggression involvement. No interactions between conflict and substance use were found during adolescence. No main effects of gender were found.

In young adulthood a significant main effect of conflict emerged for physical aggression involvement. A significant interaction between substance use and conflict also occurred in young adulthood (see Figure 1). To further interpret this and the other significant interactions, Preacher, Curran, & Bauer’s (2006) computational tools were used to plot the estimated effects of substance use on physical aggression involvement for three values of conflict: 1 SD above the mean of conflict, the mean, and 1 SD below the mean of conflict. Consistent with a moderator model of substance use and aggression, greater substance use was associated with physical aggression involvement for those 1 SD above the mean in conflict (B = 0.08, t(724) = 2.47, p = .01). Substance use was not associated with physical aggression involvement for those at the mean level of conflict or for those 1 SD below the mean in conflict. No main effects of gender were found.

Figure 1.

Interaction between substance use and conflict on physical dating aggression in young adulthood. The three lines depict the association between substance use and physical dating aggression at one SD below the mean of conflict, the mean of conflict, and one SD above the mean of conflict.

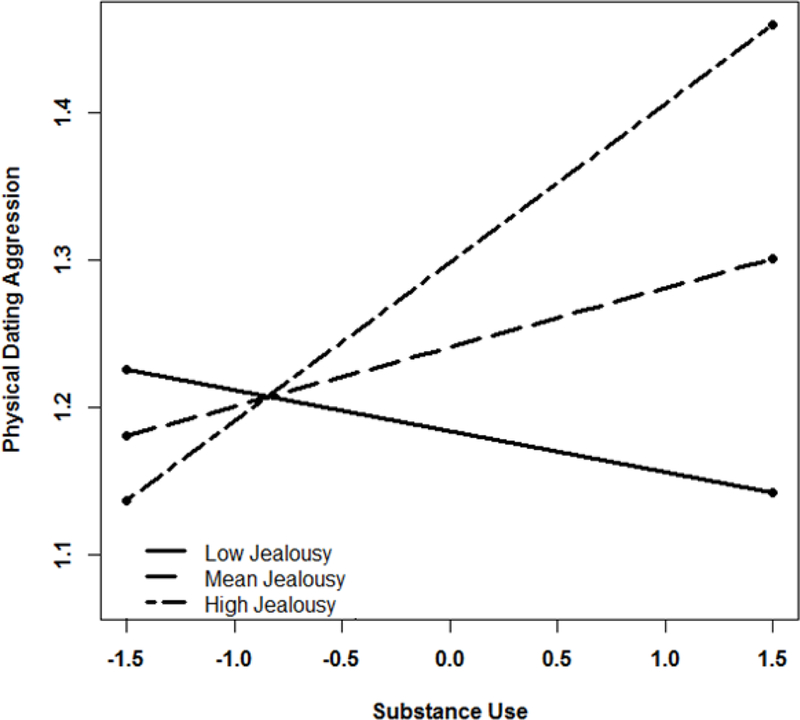

Jealousy

A significant three-way interaction emerged among age, substance use, and jealousy in association with physical dating aggression involvement. This significant three-way interaction qualified the main and moderating effects reported in Table 2. Therefore, these effects were examined separately in adolescence and young adulthood.

In adolescence, a main effect of substance use was found for physical aggression. No interactions between jealousy and substance use were found in adolescence. No main effects of gender were found.

In young adulthood, significant main effects of jealousy emerged for physical aggression involvement. Further, a significant interaction occurred between substance use and jealousy in young adulthood. Consistent with a moderator model of substance use and aggression, for those 1 SD above the mean in jealousy, greater substance use was associated with physical aggression (B = 0.11, t(724) = 2.78, p = .006). For those at the mean level and 1 SD below the mean in jealousy, substance use was not associated with physical aggression (Figure 2). No main effects of gender were found.

Figure 2.

Interaction between substance use and jealousy on physical dating aggression in young adulthood. The three lines depict the association between substance use and physical dating aggression at one SD below the mean of jealousy, the mean of jealousy, and one SD above the mean of jealousy.

Support

A main effect of substance use was found such that greater substance use was associated with greater and physical dating aggression involvement. Further, a main effect of support was found for physical dating aggression involvement, such that more supportive relationships were associated with less physical aggression. No main effects of gender were found. No two-way or three-way interactions were found for physical dating aggression involvement.

Discussion

Due to the high prevalence rates and the consequences for individuals, understanding the risk factors for the development of dating aggression has been identified as a research priority (Breiding, et al., 2014). The current study addresses this research priority by examining a moderator model of the associations among substance use, relational risk factors, and dating aggression across middle adolescence to young adulthood. Substance use was expected to generally be related to dating aggression, but the theoretical moderator model of substance use and dating aggression also posits that the associations between substance use and dating aggression varies depending on the presence of relational risk factors. Specifically, substance use was expected to have a greater effect in the context of higher risk (Foran & O’Leary, 2008a; Rothman et al., 2011). As hypothesized, main effects of relational risk and substance use emerged, particularly in adolescence. Further, conflict and jealousy moderated the associations between substance use and physical aggression in the theoretically hypothesized direction. That is, substance use was more strongly associated with physical aggression when conflict and jealousy were higher. However, these interaction patterns only emerged in young adulthood, not adolescence. Thus, relational risk factors appear to be integral to models of dating aggression in adolescence and young adulthood, but the nature of their role changes developmentally.

Patterns in Adolescence

The patterns of association in adolescence were revealed in a number of main effects between relational risk factors and dating aggression. In most instances, relational risk factors were associated with greater risk for dating aggression involvement in adolescence. Interestingly, the main effects of relational risk factors were not qualified by interactions with substance use in adolescence. Thus, these findings not only underscore the importance of relational risk factors for understanding dating aggression, but also suggest that these risk factors are directly associated with dating aggression in adolescence. Substance use was also significantly associated with adolescent physical dating aggression, which aligns with a great deal of previous work demonstrating links between substance use and involvement in adolescent dating aggression (Epstein-Ngo et al., 2013; Rothman et al., 2011). Such findings point to substance use as a particularly salient marker of risk for physical dating aggression involvement during adolescence.

Despite the influence of both substance use and relational risk factors on physical dating aggression involvement, they did not interact in adolescence. That is, the associations between substance use and dating aggression did not vary by the levels of relational risk factors. Thus, the pattern of results suggests that both substance use and relational characteristics make important, yet independent contributions to risk for dating aggression during adolescence. These findings provide further evidence that both relational risk factors and substance use are indeed important aspects of theoretical models aiming to understand dating aggression. Additionally, they highlight the importance of both focusing on both relational risk and substance use in efforts to reduce dating aggression among adolescents.

A Moderator Model in Young Adulthood

Conflict and jealousy were consistently associated with physical dating aggression involvement in young adulthood. Unlike in adolescence, however, these main effects in adulthood were often qualified by significant interactions between these two relational risk factors and substance use. In particular, greater substance use was associated with physical aggression for those high in conflict, but not those low in conflict. Similarly, greater substance use was associated with physical aggression for those high in jealousy, but not those low in jealousy. In effect, a moderator model of substance use and physical dating aggression in young adulthood was supported. Consistent with a theoretical moderator model, this pattern indicates that individuals who have lower quality relationships are more apt to be involved in physical dating aggression as substance use increases. This pattern may emerge because greater relationship risk heightens the intensity and frequency of conflict or jealousy. Substance use then functions as a proximal risk factor, distorting interactions with the partner and reducing inhibitions. In this way, the relationship risk factors work in tandem with substance use contributing to escalation into physical dating aggression involvement (Leonard, 1993). These findings indicate that increased substance use is not sufficient to meet a threshold for physical dating aggression in the context of higher quality romantic relationships. Indeed, this is consistent with patterns in adulthood that suggest that some substance use, such as alcohol use, is not problematic among high-functioning couples. In fact, among adults, drinking together is positively associated with marital quality (Homish & Leonard, 2005). Thus, although current theoretical models of dating aggression typically remain agnostic regarding the relative importance of risk factor domains, these patterns may suggest that relationship risk is necessary for the presence of dating aggression.

Prior work with adults has found such patterns of moderation regarding individual risk factors and in a few cases relational risk factors (Foran & O’Leary 2008a, 2008b; Leonard & Senchak, 1996). The current study extends these findings to dating relationships in young adulthood. The replication of patterns found in the adult and marital literatures have important implications for intervention development. Intervention programs targeting improvements in couple functioning, as well as those offering substance use treatment, have been found to lead to declines in interpersonal violence by adult and married couples (McCollum & Stith, 2008; Murphy & Ting, 2010). The current findings suggest that interventions in young adulthood may similarly benefit from the incorporation of romantic relationship skill development.

Developmental Differences

Consistent with hypotheses, the moderating role of relational risk factors was stronger in young adulthood than in adolescence. Such a pattern is congruent with prior work suggesting that the main effect of substance use diminishes developmentally, whereas moderating factors become increasingly important in explaining the associations between substance use and dating aggression (Reyes et al., 2011). In other words, substance use in adolescence may be highly likely to increase risk for dating aggression. In contrast, in young adulthood, substance use may not always be problematic as it becomes developmentally normative and its effect dependent on other factors (Chen & Jacobson, 2012).

An alternative explanation for these developmental shifts is that the importance of romantic relationship qualities increases as adolescents develop into young adulthood. Indeed, a developmental task theory proposes that romantic relationships are an emerging developmental task in adolescence and become a salient development task in young adulthood (Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Cauffman, Spieker & The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2009; Roisman, Masten, Coatsworth, & Tellegen, 2004). Consistent with this theory, youth rank their romantic partners higher on a hierarchy of support figures as they transition from adolescence to adulthood (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992); romantic relationships also become more serious, committed, intimate, and interdependent (see Furman & Winkles, 2011). Romantic relationship characteristics may be less likely to moderate links between substance use and dating aggression in adolescence because such characteristics are less significant then. The developmental changes found in the current study may have occurred because the moderator effects of relationship quality only emerge after romantic relationships become a salient task in young adults’ lives.

Gender

Few significant main effects of gender were found in the current study. A lack of gender effects suggests similar rates of dating aggression across genders, a finding which is consistent with prior patterns in both adolescence and young adulthood (Brooks-Russell, Foshee, & Reyes, 2014). Unfortunately, the current study was not able to examine whether the observed interactions among substance use, relational risk factors, and age varied by gender because of the reductions in power that would have resulted from adding seven additional terms to the multilevel models. Thus, work with larger samples should aim to understand whether these patterns differ across genders, because such differences may have important implication for intervention efforts.

Limitations, Implications, and Future Directions

The present study addressed several important limitations within the existing literature. It assessed a moderator model of substance use and relational risk factors across adolescence and young adulthood. Thus, it allowed for a developmental examination of these patterns, identifying periods wherein relationship qualities may emerge as especially important. It also focused on relational risk factors, which have been understudied despite their importance in conceptual models of dating aggression (Reese-Weber & Johnson, 2013). Finally, the present study is strengthened by the assessment of these relational risk factors using multiple methods, including both self-report and interview measures.

Despite these strengths, the present study had several limitations. First, although associations were examined across a wide age range, only concurrent links among relational risk factors, substance use, and dating aggression were examined. Further, these associations within a theoretical moderator model that proposes that the links between substance use and dating aggression vary across levels of relational risk factors. However, other iterations of these patterns are certainly possible; for example, dating aggression itself may contribute to substance use patterns. The present findings also do not reflect longitudinal changes; that is, it is unclear how substance use and relational risk factors may interact to predict changes in dating aggression across time. Future work should aim to better determine the directionality of these links by examining how changes in substance use and relational risk factors may longitudinally predict increases in dating aggression.

Additionally, although the current study assessed both dating aggression perpetration and victimization, reports were made only by one member of the dyad. Further, the predominance of bidirectional aggression in the current study did not allow for analyses examining unidirectional perpetration and victimization. Further work assessing aggression from both partners’ perspective and unidirectional aggression is necessary. Finally, future work should also more comprehensively address a theoretical moderator model by examining relational and individual risk factors simultaneously. Doing so would allow us to integrate these sets of risk factors, and more fully assess how spheres of risk contribute to the etiology of dating aggression.

Conclusion

Dating aggression has been identified as a priority public health concern. Although substance use is a known robust risk factor for dating aggression involvement, variation exists. The current study addressed the research priority of dating aggression by examining a moderator model of the associations among substance use, relational risk factors, and dating aggression over a nine year period from middle adolescence to young adulthood (15-24 years of age). Findings from the current underscore important developmental patterns with regard to risk for dating aggression. Despite known robust associations between substance use and dating aggression (Epstein-Ngo et al., 2013; Rothman et al., 2011), findings indicate that substance use is not uniformly related to dating aggression. Rather, both one’s age and the nature of one’s romantic relationship play important roles. Taken together, the current patterns suggest that as the field strives to understand and reduce dating aggression, incorporating interactions among levels of risk is essential to address the heterogeneity within dating aggression. These multiple levels of risk may be especially likely to highlight the contexts in which dating aggression increases thereby better informing intervention and prevention efforts.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Grant 050106 from the National Institute of Mental Health (W. Furman, P.I.) and Grant 049080 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (W. Furman, P.I.). The preparation of this manuscript was also supported by F31 AA023692 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (C. Collibee, P.I.

Appreciation is expressed to the Project Star staff for their assistance in collecting the data, and to the Project Star participants and their partners, friends and families.

Footnotes

Data Sharing Declaration

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- Breiding MJ, Chen J, & Black MC (2014). Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010 Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Russell A, Foshee VA, & Reyes HLM (2015). Dating Violence In Gullotta TP, Plant RW, & Evans M (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems (pp. 559–576). New York, NY: Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, & Crosby L (1997). Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development, 6, 184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, & Kim HK (2007). Typological approaches to violence in couples: A critique and alternative conceptual approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3, 231–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, & Crosby L (2003). Physical and psychological aggression in at- risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, & Jacobson KC (2012). Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collibee C, & Furman W (2016). Chronic and acute relational risk factors for dating aggression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 763–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, & Kam CM (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6, 330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Friedlander L, Pepler D, Craig W, & Laporte L (2010). The ecology of adolescent dating aggression: Attitudes, relationships, media use, and socio-demographic risk factors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19, 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J & Owens G (1996). Current Relationships Interview and scoring system. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/measures/content/cri_manual_4.pdf, State University of New York at Stony Brook. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert LL, Herting JR, & Thompson EA (1996). The drug involvement scale for adolescents (DISA). Journal of Drug Education, 26, 101–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Ngo QM, Cunningham RM, Whiteside LK, Chermack ST, Booth BM, Zimmerman MA, & Walton MA (2013). A daily calendar analysis of substance use and dating violence among high risk urban youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 130, 194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, & Rothman E (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 131, 71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Washburn IJ, Tiberio SS, & Capaldi DM (2015). Changes in the associations of heavy drinking and drug use with intimate partner violence in early adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, & O’Leary KD (2008a). Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1222–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, & O’Leary KD (2008b). Problem drinking, jealousy, and anger control: Variables predicting physical aggression against a partner. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W (2001). Working models of friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18, 583–602. doi: 10.1177/0265407501185002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Buhrmester D (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Buhrmester D (2009). The Network of Relationships Inventory: Behavioral Systems Version. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 470–478. doi: 10.1177/016525409342634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Winkles JK (2011). Transformations in heterosexual romantic relationships across the transition into adulthood: “Meet me at the bleachers… I mean the bar” In Laursen B & Collins WA (Eds.), Relationship pathways: From adolescence to young adulthood (pp. 209–213). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, & Main M (1985/1998). Adult Attachment Interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR (2013). Alcohol and aggression: Theories and mechanisms. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Manning WD, & Longmore MA (2005). The romantic relationships of African-American and White adolescents. The Sociological Quarterly, 46, 545–568. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Soto DA, Manning WD, & Longmore MA (2010). The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Social Science Research, 39, 863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, & Gilreath TD (2007). How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science, 8, 206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, & Blackwell M (2011). Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, & Longmore MA (2015). The age-IPV curve: Changes in the perpetration of intimate partner violence during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 708–726. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0158-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, & Lohman BJ (2007). Dating violence victimization, relationship satisfaction, mental health problems, and acceptability of violence: A comparison of men and women. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA (1994). Conflict resolution styles in gay, lesbian, heterosexual nonparent, and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 705–722. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Orengo-Aguayo R, Langer A, & Brock RL (2012). The impact and consequences of partner abuse on partners. Partner Abuse, 3, 406–428. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE (1993). Drinking patterns and intoxication in marital violence: Review, critique, and future directions for research In Alcohol and interpersonal violence: Fostering multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 253–280). Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, & Senchak M (1993). Alcohol and premarital aggression among newlywed couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 11, 96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, & Senchak M (1996). Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105, 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, & Moore EWG (2014). On the joys of missing data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 151–162. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF, & Swett B (2002). Violence and intimacy in close relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 570–586. [Google Scholar]

- McCollum EE, & Stith SM (2008). Couples treatment for interpersonal violence: A review of outcome research literature and current clinical practices. Violence and Victims, 23, 187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, & O’Leary KD (1989). Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical psychology, 57, 579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, & Ting L (2010). The effects of treatment for substance use problems on intimate partner violence: A review of empirical data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen BO (1998-2011). Mplus User’s Guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M (2005). Teen dating violence: A review of risk factors and prevention efforts. Harrisburg: VAWnet, National Resource Centre on Domestic Violence and Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, & Slep AM (2003). A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP320301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SM, & Wong PTP (1989). Multidimensional jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6, 181–196. doi: 10.1177/026540758900600203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reese-Weber M, & Johnson AI (2013). Examining dating violence from the relational context In Cunningham HR and Berry WF (Eds.), Handbook on the Psychology of Violence. New York, NY: Nova Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, & Ennett ST (2012). Heavy alcohol use and dating violence perpetration during adolescence: Family, peer and neighborhood violence as moderators. Prevention Science, 13, 340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Tharp AT, Ennett ST, & Bauer DJ (2015). Substance use and physical dating violence: the role of contextual moderators. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, & O’Leary KD (1989). The development of a model of courtship aggression In Pirog-Good MA & Stets JE (Eds.), Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues (pp.53–71). New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Masten AS, Coatsworth JD, & Tellegen A (2004). Salient and emerging developmental tasks in the transition to adulthood. Child Development, 75, 123–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Cauffman E, & Spieker S (2009). The developmental significance of adolescent romantic relationships: Parent and peer predictors of engagement and quality at age 15. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1294–1303. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9378-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Reyes LM, Johnson RM, & LaValley M (2011). Does the alcohol make them do it? Dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiologic Reviews, 34, 103–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Fals-Stewart W, & Leonard KE (2003). Domestic violence treatment referrals for men seeking alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 24, 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Rhatigan DL, Fite PJ, & Stuart GL (2011). Dating violence victimization and alcohol problems: An examination of the stress-buffering hypothesis for perceived support. Partner Abuse, 2, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, & Cornelius JR (2012). Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 236–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, & Saltzman LS (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 941–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW (2009). A gendered approach to adolescent dating violence: Conceptual and methodological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, & Laporte L (2008). Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 622–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]