Abstract

Bacterial pathogens have evolved strategies that enable them to invade tissues and spread within the host. Enterococcus faecalis is a leading cause of local and disseminated multidrug-resistant hospital infections, but the molecular mechanisms used by this non-motile bacterium to penetrate surfaces and translocate through tissues remain largely unexplored. Here we present experimental evidence indicating that E. faecalis generates exopolysaccharides containing β-1,6-linked poly-N-acetylglucosamine (polyGlcNAc) as a mechanism to successfully penetrate semisolid surfaces and translocate through human epithelial cell monolayers. Genetic screening and molecular analyses of mutant strains identified glnA, rpiA and epaX as genes critically required for optimal E. faecalis penetration and translocation. Mechanistically, GlnA and RpiA cooperated to generate uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) that was utilized by EpaX to synthesize polyGlcNAc-containing polymers. Notably, exogenous supplementation with polymeric N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) restored surface penetration by E. faecalis mutants devoid of EpaX. Our study uncovers an unexpected mechanism whereby the RpiA-GlnA-EpaX metabolic axis enables production of polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides that endow E. faecalis with the ability to penetrate surfaces. Hence, targeting carbohydrate metabolism or inhibiting biosynthesis of polyGlcNAc-containing exopolymers may represent a new strategy to more effectively confront enterococcal infections in the clinic.

Author summary

Enterococcus faecalis is a microbial inhabitant of the human gastrointestinal tract that can cause lethal infections. Typically classified as a non-motile bacterium, E. faecalis can readily migrate and translocate across epithelial barriers to invade distant organs. Nevertheless, the molecular pathways driving enterococcal invasive attributes remain poorly understood. In this study, we uncover that E. faecalis produces a polyGlcNAc-containing extracellular glycopolymer to efficiently migrate into semisolid surfaces and translocate through human epithelial cell monolayers. Our work provides evidence that non-motile bacterial pathogens can exploit endogenous carbohydrate metabolic pathways to penetrate surfaces. Thus, targeting glycopolymer biosynthetic programs might be useful to control infections by Gram-positive cocci in the clinic.

Introduction

Microbes use a variety of strategies to obtain nutrients and ensure survival. While motility could be used as a means for accessing nutrient sources, non-motile bacterial species require unconventional mechanisms to accomplish this goal. Enterococcus faecalis is a non-motile, facultative anaerobic bacterium that inhabits the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1]. However, hypervirulent E. faecalis strains resistant to multiple antibiotics often cause hospital-acquired urinary tract, wound and abdominal infections, as well as bacteremia and infective endocarditis [1]. Enterococci can adhere to and invade host tissues in order to act as lethal pathogens. Indeed, E. faecalis translocation across the intestinal barrier enables bacterial spread and colonization of distal anatomical sites [2, 3]. Interestingly, E. faecalis extra-intestinal translocation appears to be promoted by association with epithelial cells in aggregates [3], a process that is partly mediated by the synthesis of adhesins [3–5] and additional unknown factors.

Enterococci produce diverse cell wall-anchored polysaccharides [6–8], which generally consist of repeating units of oligosaccharides that are associated with bacterial surfaces through linkage to cell membrane, peptidoglycan or other unknown mechanisms [7, 9]. E. faecalis displays an extensive surface glycome, including wall teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid polymers, capsular polysaccharides [7, 10], and the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen (EPA), which is a rhamnopolysaccharide. EPA, mainly composed of glucose, rhamnose, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), and galactose that appears to be buried within the cell wall, thus precluding interaction with host cells [7]. In addition to these polysaccharides, a new glycopolymer was recently discovered on the surface of E. faecalis cells by immunofluorescence assays using the human IgG monoclonal antibody (mAb) F598, which specifically binds to β-1,6-linked GlcNAc polysaccharides [8, 11]. While this putative polyGlcNAc-like polymer has not been studied in E. faecalis, other reports have characterized similar polysaccharides that react with mAb F598 [12, 13], termed either PIA (for polysaccharide intercellular adhesin) in Staphylococcus epidermidis [14, 15] or PNAG (for polymeric N-acetyl glucosamine) in Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens [16, 17]. Of note, these extracellular glycopolymers consist of β-1,6-linked GlcNAc residues containing 5–10% positively-charged amino groups (due to partial de-N-acetylation (GlcNH3)) as well as negative charges (resulting from O-succinylation) [8, 14–17].

E. faecalis has been shown to invade surfaces such as mammalian tissues [3, 18] and penetrate solid culture media [19], but the mechanisms driving these processes remain elusive. In the present study, we identified the molecular events and metabolic pathways that endow E. faecalis with remarkable capacity to penetrate semisolid surfaces. We found that E. faecalis produces extracellular polyGlcNAc-containing polymers to form penetrating microcolonies inside semisolid surfaces. Using diverse genetic and biochemical approaches, we determined that biosynthesis of these complex exopolymers occurs through the RpiA-GlnA-EpaX metabolic pathway. Notably, E. faecalis mutants unable to produce polyGlcNAc-containing polymers demonstrated impaired capacity to pass into semisolid surfaces and translocate through human epithelial cell monolayers.

Results

The non-motile bacterium E. faecalis penetrates semisolid surfaces

Analysis of semisolid media penetration has been useful for identifying and characterizing virulence traits in human fungal pathogens [20–23]. We sought to exploit this approach to understand the molecular mechanisms that E. faecalis utilizes to enter surfaces. Under our conditions, an indelible bacterial “colony-print” developed inside modified MOLP (medium optimal for lipopeptide production) [24], when six-day-old colonies of the clinical isolate E. faecalis were extensively washed with water to remove adventitiously associated bacterial cells from the surface of the agar. This colony-print, indicative of penetration, was not observed at agar concentrations above 1.0% (Fig 1A), and agar degradation was not evidenced once the external (non-penetrating) cells were removed. Importantly, we identified this semisolid agar-penetration trait in several clinical isolates as well as in the commensal-like strain E. faecalis OG1RF (S1A Fig). Kinetic analyses revealed that E. faecalis agar entrance was macroscopically evident 48 h post-inoculation, and that it progressed concomitantly with colony expansion (S1B Fig). Of note, the agar penetration ability of all E. faecalis strains tested in this study was not lost upon laboratory domestication. This phenomenon was not only evidenced when E. faecalis colonies were grown on culture media solidified with agarose, but also with the copolymer poloxamer-407 (MOLP-407) (S1C and S1D Fig; top), demonstrating that this process is not specific to the nature of the gelling agent.

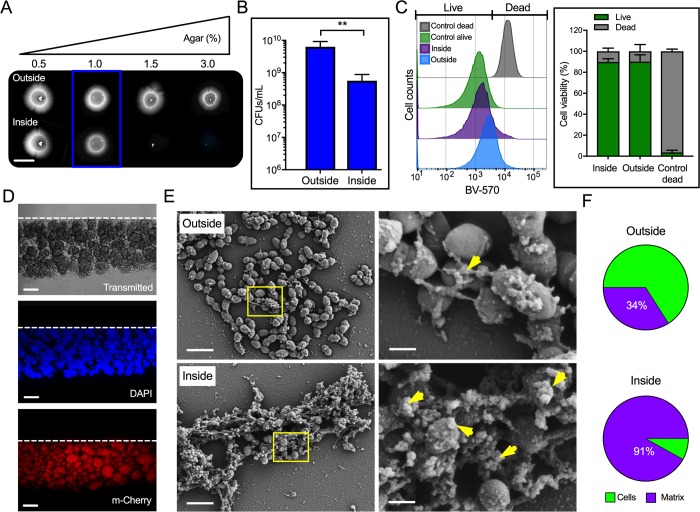

Fig 1. E. faecalis cells penetrating semisolid media are covered by an extracellular matrix.

(A—F) The capacity of E. faecalis MMH594 to penetrate semisolid MOLP was evidenced as a colony-print inside the agar after removing external non-penetrating cells. (A) Macroscopic images of colonies (outside) and penetrating bacteria (inside) on solidified medium with the indicated agar concentrations. Scale bar: 6,000 μm. (B) Quantification of internal and external cells grown on semisolid MOLP (1% agar; blue box) expressed as CFUs/mL (mean±SE; n = 6; **P<0.01; two-tailed unpaired t–test with Mann-Whitney test). Data are representative of 5 independent experiments. (C) FACS-based viability analysis of penetrating and non-penetrating E. faecalis (right; mean±SE; n = 8). (D) Side sections of E. faecalis inside semisolid MOLP as described above. Top dashed lines indicate the beginning of the agar in each section. Lower scale bar: 60 μm. (E) SEM images of aggregated and matrix-covered (yellow arrow head) invading and non-invading cells (right panels; scale bar: 400 nm). Yellow square areas were imaged at higher magnifications (left panels; scale bar: 2 μm). (F) Fractions of cells and extracellular matrix found on the surface (~111 μm2) visible in the SEM images of penetrating and non-penetrating bacteria, as quantified using automated image analysis (mean±SE; n = 3; P < 0.05; two-tailed unpaired t–test).

To quantify the number of penetrating and non-penetrating bacteria, colony forming units (CFUs) were determined from both inside and outside E. faecalis populations grown on semisolid MOLP. Some of the penetrating bacteria were able to form colonies, but the total number of CFUs obtained for this population (~5x108) was reproducibly one order of magnitude lower than that of the external cells (~6x109; Fig 1B). Similarly, the total CFUs obtained from the penetrating population grown on MOLP-407 were lower (~2x108) than the CFUs obtained for external cells (~1x109; S1D Fig, bottom). Flow cytometric analyses of penetrating and non-penetrating bacteria grown on MOLP were performed to determine the viability of these cells after staining with the live/dead dye Brilliant Violet-570 (BV-570). In contrast to the heat-killed control showing less than 5% viable cells, ~90% of the penetrating and non-penetrating population were viable under our culture conditions (Fig 1C). Together, these data indicate that E. faecalis can pass into semisolid surfaces and that the majority of the penetrating cells remain viable during this process.

The colony-print is formed by bacterial microcolonies covered by an extracellular matrix

To further understand the E. faecalis penetration process, we analyzed agar side sections of approximately 2 mm-wide obtained from six-day-old colony-prints produced by penetrating bacteria grown in MOLP. Interestingly, isolated aggregates with varying morphologies and sizes readily formed inside the agar (Fig 1D; top). Penetration was found to decrease proportionally from the center (S1E Fig; depth of ~128 μm) to the edge (S1F Fig; depth of ~6 μm) of the colony, with several aggregates penetrating deeper at the center (Fig 1D; top and S1E Fig). DAPI staining (Fig 1D; middle) and epifluorescence analysis of penetrating bacterial cells constitutively expressing m-Cherry (Fig 1D; bottom) confirmed that these internal clumps contained viable and metabolically active E. faecalis cells.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses of E. faecalis colonies were performed to determine the morphological status of external and MOLP-penetrating cells. No major changes in cell morphology were found and only normal diplococcal, clumped or isolated, bacterial cells were observed. Strikingly, however, cells within the aggregates were covered with and connected by an extracellular matrix that appeared to be more abundantly produced by invading cells than surface cells (Fig 1E). Indeed, automated SEM image analysis (see Material and Methods) determined that internal cells exhibited significantly higher matrix coverage than external cells (Fig 1F). These data indicate that E. faecalis penetrates the agar surface and that this process is accompanied by the generation of microcolonies formed by matrix-covered cells.

E. faecalis mutants defective in semisolid surface penetration

Cellular structures, such as pili, have been shown to be involved in mediating Gram-positive bacterial motility [25]. To determine whether pili expression could mediate the penetration process observed, we tested two previously generated pili-deficient E. faecalis mutants (ΔebpABC and ΔebpA), and their parental OG1RF strain [26], under our conditions. After 6 days of growth on MOLP, we found that Ebp mutants and the wild-type (WT) strain exhibited similar penetration capacities, and only a slight change on the shape of the colony-print was evidenced in the absence of pili (S2A Fig). These data suggest that the bacterial migration process is mediated by an Ebp pilus-independent mechanism.

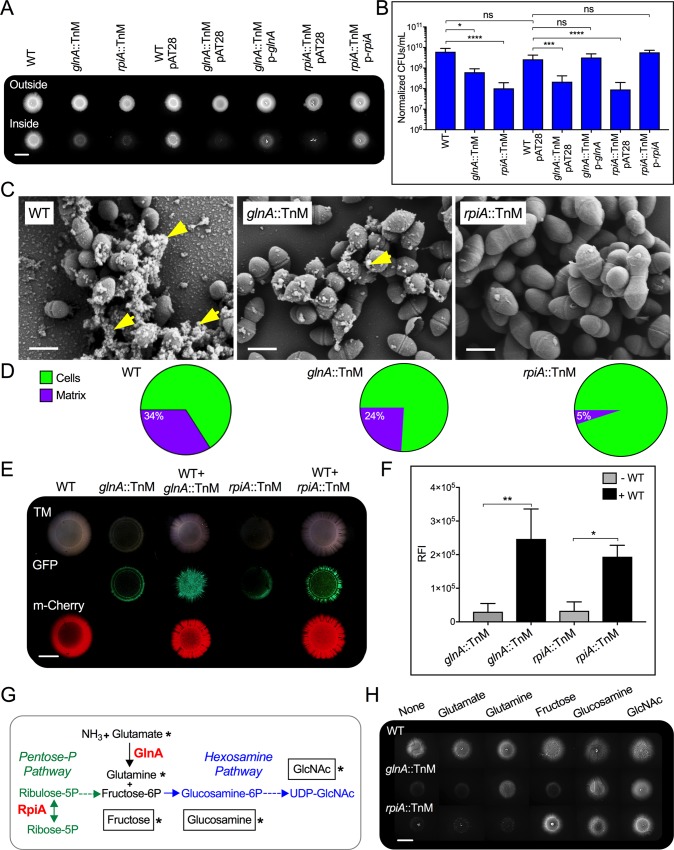

To further understand the E. faecalis semisolid surface penetration process, we performed genetic screening of a Mariner transposon insertion library. We sought to identify mutants that developed normal colonies above the agar, but were impaired in their semisolid surface-penetration capacity. Out of approximately 6,000 mutants screened, seven were found to be defective in penetration. Five of the seven mutants identified exhibited substantial growth defects and were thus excluded from subsequent studies. Of the remaining two mutants that were unable to generate WT-like colony-prints inside the agar (Fig 2A), we determined they had transposon inserts in either the glnA (glutamine synthetase) or rpiA (ribose-5-phosphate isomerase) genes. The glnA::TnM, but not the rpiA::TnM strain, exhibited a slight growth defect in liquid MOLP (S2B Fig), but both strains formed external colonies similar in size to those of WT (Fig 2A). The external and internal numbers of bacterial cells were next determined by differential CFU analysis. No significant differences were found in the CFU counts of the glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM mutants on the agar surface in comparison with their paternal strain (S2C Fig and S1 Table). However, inside the semisolid surface, the rpiA::TnM and glnA::TnM mutants exhibited a significant reduction in the CFU counts in comparison with their parental strain (6x109; Fig 2B), consistent with the visible decrease in the colony-print generated by these two transposon mutants (Fig 2A). Genetic complementation with plasmids expressing either RpiA or GlnA correspondingly restored the invading phenotype of these mutant strains (Fig 2A and 2B). SEM analysis of external cells of six-day-old colonies revealed that while all strains exhibited diplococcal morphology, rpiA::TnM cells were bigger than both WT and glnA::TnM cells (Fig 2C). Most importantly, the extracellular matrix normally covering and connecting WT E. faecalis cells (Figs 1E and 2C) was either decreased or almost absent in glnA::TnM or rpiA::TnM mutants, respectively (Fig 2C and 2D). Together, these results indicate that GlnA and RpiA are necessary for efficient penetration of E. faecalis into semisolid surfaces, and that mutants lacking these genes also failed to produce the extracellular matrix that naturally covers the WT cells.

Fig 2. Mutations in glnA and rpiA cause defects in agar penetration that can be restored by extracellular factors or metabolic substrates.

(A and B) Semisolid surface penetration by WT E. faecalis MMH594 or the Mariner transposon mutants glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM, with and without the empty vector pAT28, or in-trans complemented mutants with pAT28 vector harboring their corresponding WT allele (p-glnA and p-rpiA). (A) Macroscopic images of colonies (outside) and invading areas of WT and mutants grown on semisolid MOLP. Scale bar: 6,000 μm. (B) Quantification of cells inside the semisolid surface expressed as CFUs/mL, normalized to their initial absorbance values prior to serial dilutions; (mean±SE; n = 6; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; **** P<0.0001 for both the one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test; nonsignificant, ns). (C) SEM analyses of external bacterial cells. Extracellular matrix is indicated by yellow arrows (scale bar: 400 nm). (D) Fractions of cells and extracellular matrix found on the visible surface of SEM images of non-penetrating strains, quantified through automated image analyses. The pie chart of the non-penetrating WT is based on the same image data used in Fig 1F, outside. (E) Images of colony-prints of WT expressing m-Cherry grown alone or mixed with either glnA::TnM (WT+ glnA::TnM) or rpiA::TnM (WT+ rpiA::TnM) expressing GFP at a 1:2 (WT to mutant) ratio. As control, single cultures of glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM were spot-inoculated on MOLP. Scale bar: 4,000 μm. (F) Relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of the colony-prints expressing GFP generated by either mutant alone or co-cultured with WT was measured using Image J. (mean±SE; n = 3; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). (G) Metabolic pathways depicting penetration-deficient mutants. RpiA catalyzes the reversible reaction (double-headed arrow) between ribose-5-phosphate (Ribose-5P) and ribulose-5-phosphate (Ribulose-5P). Through the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (Pentose-P-Pathway), RpiA could supply cellular pools of fructose-6-phosphate (Fructose-6P). GlnA synthesizes cellular glutamine from ammonia (NH3) and glutamate. Fructose-6P and glutamine could be used by the cell to form glucosamine-6-phosphate (Glucosamine-6P) that serves as intermediate to generate UDP-N-acetyl glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (Hexosamine pathway). (H) WT or transposon mutant colonies were assessed for penetration in media without or with exogenous 5–10 mM glutamate, glutamine, fructose, glucosamine and GlcNAc. Scale bar: 6,000 μm. Substrates supplied (asterisk) for metabolic complementation assays (G).

Wild-type extracellular factors metabolically rescue semisolid surface penetration by E. faecalis mutants devoid of GlnA and RpiA

We next determined the molecular mechanisms by which GlnA and RpiA promote E. faecalis semisolid surface penetration. Since both enterococcal mutants unable to pass into agar failed to produce the extracellular matrix evident in the colony-prints of the parental strain (Figs 1E, 1F, 2C and 2D), we hypothesized that extracellular factors produced by WT cells could restore penetration by strains lacking GlnA and RpiA. To test this idea, WT cells expressing m-Cherry were independently mixed with GFP-labeled glnA::TnM or rpiA::TnM mutants, and colony-prints were analyzed after 6 days via fluorescence stereomicroscopy. WT invading cells formed a bright red fluorescent colony-print, whereas monocultures of glnA::TnM or rpiA::TnM showed decreased invasion capacity as evidenced by minimal GFP-derived fluorescence. However, a remarkable increase in GFP-positive invading cells was found when either mutant was co-cultured with WT cells (Fig 2E). These observations were consistent with the higher relative fluorescent intensity (RFI) observed with the colony-prints from mutants co-cultured with WT than those obtained from the monoculture area (Fig 2F). Hence, extracellular factors produced by the WT strain can restore the agar penetration defects intrinsic to the glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM mutant cells.

GlnA and RpiA participate in key metabolic pathways (Fig 2G). GlnA plays an essential role in the metabolism of nitrogen by catalyzing the condensation of glutamate and ammonia (NH3) to generate glutamine [27]. RpiA catalyzes the reversible conversion of ribose-5-phosphate to ribulose-5-phosphate, a central enzymatic reaction in the pentose phosphate pathway [28]. We hypothesized that the metabolic functions of GlnA and RpiA may converge in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, where the glutamine produced by GlnA, together with fructose-6-phosphate generated from metabolites of the pentose phosphate pathway, could promote the formation of glucosamine-6-phosphate [29, 30]. We further postulated that decreased ability to penetrate MOLP by glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM mutants could be a consequence of alterations in the levels of intracellular hexosamine biosynthetic pathway metabolites (Fig 2G). To test these hypotheses, we performed a metabolic complementation assay by supplementing exogenous substrates related to this pathway. Semisolid surface penetration by WT cells was not altered by addition of any of the substrates to the medium (Fig 2H). However, exogenous glutamine, glucosamine and GlcNAc, but not glutamate or fructose, rescued the defective penetration phenotype of glnA::TnM cells. In addition, penetration of rpiA::TnM mutants was restored by fructose, glucosamine or GlcNAc supplementation (Fig 2H). These data suggest that low availability of cellular fructose-6-phosphate (in rpiA::TnM) or glutamine (in glnA::TnM) compromises the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and consequently, decreases the cellular levels of products of this pathway such as glucosamine-6P and UDP-GlcNAc that are required for enterococcal migration into semisolid MOLP.

GlcNAc-derived exopolysaccharides are necessary for E. faecalis semisolid surface penetration

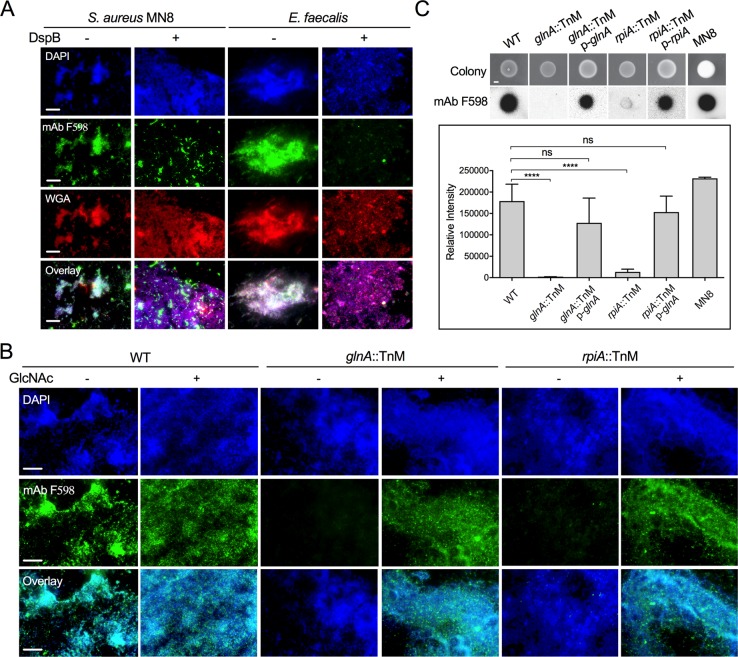

We postulated that products derived from UDP-GlcNAc could mediate agar penetration by E. faecalis. Interestingly, we observed that E. faecalis readily produced extracellular GlcNAc-containing products, as evidenced by staining with wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; Fig 3A) that binds to GlcNAc residues [31]. S. aureus MN8, a bacterial strain that has been shown to secrete GlcNAc-derived polymers[8, 32], was used in this assay as a positive control (Fig 3A).

Fig 3. polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides are necessary for E. faecalis semisolid media penetration.

(A and B) Immunofluorescence analysis of cells stained with either Texas red-conjugated WGA or mAb F598, which specifically binds to β-1,6-linked GlcNAc polysaccharides. To visualize antibody binding to GlcNAc-containing polymers, cells were reacted with a secondary anti-human IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488 (green fluorescence). DAPI was used to stain bacterial DNA (blue fluorescence). (A) Staphylococcus aureus MN8 (positive control) and E. faecalis MMH594 non-penetrating cells from MOLP-grown colonies were treated with or without 300 μg/mL Dispersin B (DspB), an enzyme that degrades β-1,6 bonds. (B) Cells of E. faecalis WT and transposon mutants grown on MOLP for 6 days with (+) or without (-) 10 mM GlcNAc were tested for binding to mAb F598 as described above. (C) Colony hybridization blot (top panel) of 24 hours-grown-colonies of WT and glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM alone or harboring the pAT28 vector containing their corresponding WT allele (p-glnA and p-rpiA). The relative intensity obtained upon incubation with mAb F598 was calculated for each colony using Image J (lower panel); (mean±SE; n = 8; ****P<0.0001 for both the one-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparison test). Scale bars (A and B): 20 μm and (C): 1000 μm.

Since UDP-GlcNAc is a common precursor for the synthesis of bacterial cell walls and some polyGlcNAc exopolysaccharides, such as PNAG (PIA) [9], we hypothesized that polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides could mediate enterococcal semisolid surface penetration. To test this, we examined the surface of enterococcal colonies grown on MOLP by immunofluorescence using the monoclonal antibody (mAb) F598, which specifically recognizes β-1,6-linked polyGlcNAc polymers [8, 11]. We detected polyGlcNAc-containing polymers on both the WT enterococcal cell surface and the positive control S. aureus (Fig 3A). The staining specificity was confirmed with an S. aureus strain (Δica) unable to produce the polyGlcNAc polymer, PNAG (PIA) [32] (S3A Fig). Further validating these results, the presence of these polymers was decreased and severely mislocalized in both WT E. faecalis and the positive control S. aureus MN8 upon treatment with Dispersin B (DspB; Fig 3A), an enzyme that specifically cleaves the β-1, 6 linkage of glucosamine and depolymerizes PNAG (PIA) [33]. DspB treatment did not affect the binding of WGA to any WT strain (Fig 3A), suggesting that this lectin may react with additional cellular components different from β-1,6-linked GlcNAc polymers. Indeed, WGA has been shown to detect not only GlcNAc residues, but also β-1,4-linked GlcNAc oligomers [31] such as the exposed-GlcNAc residues of the peptidoglycan layer of Gram (+) bacteria [34]. This observation was further confirmed by the remaining positive WGA signal found in the PNAG (PIA)-deficient S. aureus mutant Δica (S3A Fig). In contrast to WT E. faecalis, polyGlcNAc-containing polymers were not detected in glnA::TnM or rpiA::TnM mutants stained with mAb F598 (Fig 3B). Strikingly, metabolic complementation using GlcNAc-supplemented media restored polyGlcNAc-derived polysaccharide production (Fig 3B) and semisolid surface penetration (Fig 2H) in these two mutant strains.

We performed colony immunoblot assays to define the localization of polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides. Non-lysed E. faecalis cells from colonies grown on MOLP were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with mAb F598 to detect polymer production. Consistent with our microscopy results, we only observed a strong signal in the WT strain but not in glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM mutants. Complementation by either addition of exogenous GlcNAc to the media (S3B and S3C Fig) or with plasmids expressing either RpiA or GlnA correspondingly (Fig 3C) restored extracellular polyGlcNAc-derived polysaccharide production. Similarly, the control S. aureus MN8 also demonstrated positive detection in these analysis (Fig 3C; and S3C Fig).

To further characterize the exopolysaccharides produced by E. faecalis grown on semisolid surfaces, we used calcofluor white (CFW), a fluorescent dye known to bind surface fibrillar exopolysaccharides harboring either β-1,3 or β-1,4 linkages such as cellulose and chitin [35–37]. In contrast to the CFW positive binding observed with Candida albicans colonies, a strain known to synthesize chitin (a β-1,4-linked oligosaccharide) [38], E. faecalis colonies did not produce CFW-reactive exopolysaccharide under our conditions. Similarly, the negative control Escherichia coli DH5α [39], did not exhibit any fluorescence with CFW in the culture media (S3D Fig). Taken together, these data suggest that E. faecalis produces β-1,6-linked GlcNAc-containing polysaccharides that are extracellularly localized and necessary for agar penetration capacity.

EpaX is required for exopolysaccharide-mediated semisolid surface penetration

In S. aureus, the synthesis of polyGlcNAc polymers, such as PNAG (PIA), depends on the expression of biosynthetic enzymes encoded by the icaADBC operon [40–42]. IcaA is a glycosyltransferase that uses UDP-GlcNAc as a substrate [40], and IcaB is responsible for the deacetylation of PNAG (PIA) [43]. Since in silico analyses revealed that E. faecalis does not have homologs of these genes, we used Nanostring technology [44, 45] to identify potential glycosyltransferase genes that could be involved in synthesizing polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides that mediate E. faecalis agar penetration. Transcript levels of genes encoding putative glycosyltransferases were determined in cell lysates from E. faecalis colonies undergoing agar penetration, normalizing gene expression to multiple independent housekeeping genes (S2 Table). Several genes demonstrated significant expression changes during the semisolid surface entering process (S4A Fig). We focused on EF2170 (epaX) because its transcript levels were markedly elevated in cells that entered the agar, compared with non-penetrating cells on the surface (S4A Fig). To determine the role of EpaX in enterococcal semisolid surface penetration, we tested a strain harboring mutations in the epaX gene (EF2170) [46]. This mutant had no apparent growth defects under our conditions (Fig 4A and S4B Fig), but demonstrated a substantial defect in agar penetration, which was corrected upon genetic complementation with a plasmid expressing EpaX (Fig 4A). Further confirming these results, deletion of epaX in a closely-related E. faecalis strain (MMH594) also resulted in attenuated semisolid surface invasion (S4C Fig). Similarly to glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM strains, SEM analysis of external E. faecalis cells in six-day-old colonies revealed that ΔepaX showed a profound reduction in the extracellular matrix normally covering and connecting its WT counterpart (Fig 4B and 4C).

Fig 4. EpaX is necessary for E. faecalis semisolid surface penetration and synthesis of polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides.

(A—H) Penetration analysis for E. faecalis VE14089 (closely-related to MMH594) and the EpaX-deficient mutant (ΔepaX) (A) Invasion was tested for mutant and its parental strain with (right panel) or without exogenous GlcNAc, glucosamine or fructose. Complementation in-trans of epaX WT allele restored invasion (p-epaX). Scale bar: 6,000 μm. (B) SEM images of external cells at (left) low magnification (scale bar: 5 μm). Yellow squared areas were imaged at higher magnifications (right; scale bar: 1 μm), where extracellular matrix is indicated (yellow arrow head). (C) Fractions of cells and extracellular matrix found on the visible surface of SEM images of non-penetrating WT and mutant strains. (mean±SE; n = 3; *P<0.05; two-tailed unpaired t–test) (D) Glycosyl composition of polysaccharides extracted from liquid cultures of WT and ΔepaX grown to exponential phase in MOLP broth (mean±SE; n = 3). (E) Fluorescence microscopy images of external cells from MOLP-grown colonies incubated with mAb F598 to visualize GlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides (green fluorescence). DAPI was used to stain bacterial DNA (blue fluorescence). Scale bar: 20 μm. (F) Immunoblot (left panel) of 24-hour-grown colonies. The relative intensity obtained upon incubation with mAb F598 was calculated for each colony using Image J, right panel; (mean±SE; n = 8; ****P<0.0001 for both one-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparison test). Scale bar: 1000 μm. (G) Semisolid media penetration of WT and ΔepaX grown with and without 200 μM PNAG purified from S. aureus MN8. Scale bar: 5,000 μm. (H) Quantification of invasion was expressed as CFUs/mL (mean±SE; n = 4; **P<0.01 for both the one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

To further characterize the role of EpaX in the synthesis of polysaccharides under our penetration conditions, we used polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with subsequent alcian blue and silver nitrate staining to analyze the polysaccharide content of WT and ΔepaX extracted from colonies grown on MOLP. Consistent with previous results [46], a band disappeared in the ΔepaX strain, which was restored upon genetic complementation (S4D Fig), suggesting drastic changes in the oligosaccharide composition between these strains. Indeed, further analysis using acid methanolysis combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) determined that loss of EpaX severely altered the glycosyl composition of E. faecalis (Fig 4D). Specifically, ΔepaX stains demonstrated increased glucose content that was accompanied by a profound reduction in rhamnose, GalNAc and GlcNAc, compared with their parental strain (Fig 4D). These data suggested that EpaX might be required for the synthesis of GlcNAc-containing exopolymers that are necessary for optimal E. faecalis semisolid surface penetration. To test this idea, we performed immunofluorescence analyses using mAb F598. Notably, E. faecalis ΔepaX was not recognized by the antibody (Fig 4E and S4E Fig), but this defect could be corrected upon genetic complementation with a plasmid encoding EpaX (Fig 4E). The binding of WGA to E. faecalis was unaltered in the absence of EpaX (S4E Fig), suggesting that this putative glycosyl transferase is necessary to generate β-1,6-polyGlcNAc-containing polymers, but not to synthesize other GlcNAc-containing cellular components or polysaccharides detected by the lectin. Moreover, colony immunoblot assays further demonstrated that polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides were detected only in colonies from strains with a functional EpaX (Fig 4F). To define whether EpaX operates upstream or downstream of GlnA and RpiA, we tested if exogenous fructose, glucosamine or GlcNAc could rescue the defective invasive phenotype of ΔepaX, as previously observed in glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM mutants (Fig 2H). The WT parental strain formed bigger colonies and penetrated more efficiently when fructose, glucosamine and GlcNAc were supplemented. However, none of these substrates rescued penetration in ΔepaX strains (Fig 4A and S4C Fig). Supplementation of exogenous GlcNAc also failed to restore polyGlcNAc-containing polymer production by the ΔepaX strain (Fig 4E). Strikingly, however, exogenous addition of exogenous purified PNAG (PIA) from S. aureus MN8 fully restored invasion by ΔepaX strains (Fig 4G). CFUs quantification of invading cells confirmed that S. aureus MN8-derived PNAG (PIA) rescued the attenuated invasive phenotype observed in ΔepaX (Fig 4H). No major bacterial growth defects were observed upon PNAG (PIA) addition to semisolid media (S4F and S4G Fig). Together, these results demonstrate that EpaX functions downstream of GlnA and RpiA to drive β-1,6-linked polyGlcNAc polymer-mediated surface penetration in E. faecalis.

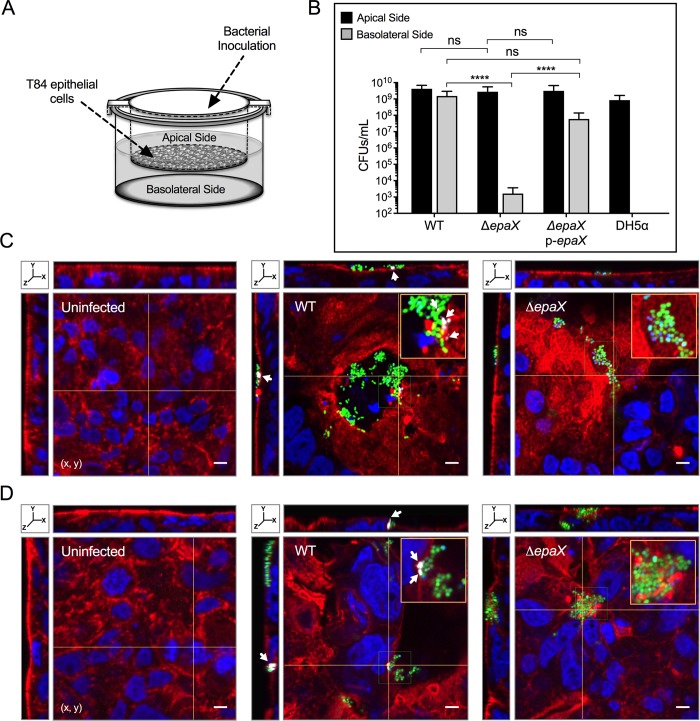

PolyGlcNAc-containing polymers are required for E. faecalis translocation

E. faecalis has the potential to translocate from the gastrointestinal tract to the blood stream [47], most likely via a paracellular mechanism that allows the bacterium to move through epithelial cell monolayers [48]. We hypothesized that E. faecalis mutants defective in biosynthesis of polyGlcNAc-containing polymers and semisolid surface penetration would also be altered for translocation through intestinal epithelial barriers. To this end, we used a previously described two-chamber transcytosis system [49, 50] where translocation is evaluated by determining the bacterial number (as CFUs) capable of passing from the apical side through T84 human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers, to the basolateral side of the chamber (Fig 5A). We found that 8 hours post-infection, the integrity of inoculated and non-inoculated monolayers exhibited transepithelial resistance values similar (~8,900 Ω/cm2) to those obtained prior to bacterial inoculation (~8,300 Ω/cm2), thus indicating that the T84 cell monolayers remained mostly intact throughout the experiment. All strains evaluated reached approximately 108−109 CFUs/mL in the apical side of all the wells tested (Fig 5B, S5A and S5B Fig). Consistent with previous reports [49, 50], the negative control E. coli DH5α was not detected in the lower chamber of any of the inserts analyzed (Fig 5B, S5A and S5B Fig), but WT E. faecalis, in sharp contrast, demonstrated a remarkable capacity to translocate in this assay. When E. faecalis mutant strains were evaluated, reduced numbers of rpiA::TnM cells (~5x102 CFUs/mL) were detected in the basolateral section in comparison with its parental WT strain (~6x107 CFUs/mL; S5A Fig). Interestingly, the glnA::TnM mutant did not show a significant decrease in translocation, likely due to metabolic complementation by exogenous glutamine present in the translocation culture medium (S5A Fig). Indeed, removing glutamine from the system drastically attenuated the translocation capacity of glnA::TnM but not WT cells (~4x102 vs. ~1x108 CFUs/mL, respectively; S5B Fig). Similarly, while WT E. faecalis moved efficiently through epithelial cell monolayers, ΔepaX demonstrated a significant decrease in translocation (~2x109 and ~1x103 CFUs/mL for WT and mutant, respectively; Fig 5B). Of note, genetic complementation of rpiA::TnM, glnA::TnM or ΔepaX cells restored the ability of each corresponding mutant strain to translocate (Fig 5B, S5A and S5B Fig). As control in our assays, we used a ΔepaB deletion strain unable to produce the glycosyl transferase EpaB (Orfde4), a protein previously shown to be necessary for efficient E. faecalis translocation through human epithelial cell monolayers [6, 49]. Surprisingly, under our conditions, the translocation ability of the ΔepaB mutant was similar to its parental strain (S6A Fig). In addition, ΔepaB was capable of producing polyGlcNAc-containing polymers at similar levels as the WT strain (S6B and S6C Fig), and exhibited normal capacity to penetrate semisolid agar (S6D Fig). These data suggest that, under our experimental conditions, the synthesis of polyGlcNAc-containing polymers is sufficient to enable surface penetration by strains devoid of EpaB.

Fig 5. E. faecalis strains devoid of polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides demonstrate defective translocation through human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers.

(A) Scheme of the two-chamber translocation system. E. faecalis VE14089 WT and derived strains inoculation occurred at the apical side. T84 human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers grown on filters separate the apical side from the lower chamber. (B) Colony forming units (CFUs/mL) of viable bacterial cells that did not pass through the monolayer (apical side) or translocated to the basolateral side after 8 hours of incubation. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a negative control (mean±SE; n = 5; ****P <0.0001 for both the one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test). (C and D) 3D reconstruction of confocal immunofluorescence images (x, y, z) of T84 human cell monolayers uninfected (left) or infected for 2 (C) or 6 (D) hours with WT (center) or ΔepaX (right) constitutively expressing GFP (green fluorescence). Alexa Fluor-594 coupled phalloidin and DAPI were used to stain the epithelial cell actin (red fluorescence) and nucleus (blue fluorescence), respectively. To visualize polyGlcNAc-containing polymers, epithelial cells and enterococci co-cultures were treated with mAb F598 antibody and reacted with the antihuman IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor-647 (gray fluorescence; white arrows). The yellow lines mark the intersection point were the x, z (top) and y, z (left) orthogonal views of reconstructed Z-sections were taken. Scale bar: 5 μm. The orange square represents a 2X-magnified view of the selected area in x, y planes (green square).

To further characterize E. faecalis translocation, T84 human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers were infected with GFP-labeled E. faecalis parental and mutant strains. Immunofluorescence analyses were performed by reacting each sample with phalloidin, DAPI and mAb F598 to visualize the actin cytoskeleton, nuclei (and bacterial DNA) and polyGlcNAc-containing polymers, respectively. Laser scanning confocal microscopic analyses of stained samples were carried out to localize bacteria within the T84 monolayers. After two hours of infection, we observed that enterococci were frequently co-localized with actin-rich areas (Fig 5C and S5C and S5D Fig). Moreover, the orthogonal views showed that bacterial aggregates concentrated on the top of the monolayers where parental strains (WT) formed surface invaginations, in comparison with the smooth surface of intact T84 human intestinal epithelial monolayers (Fig 5C, S5C and S5D Fig), hence suggesting that WT strains alter the actin cytoskeleton during the translocation process. These surface perturbations were observed to a lesser extent in monolayers infected with either ΔepaX (Fig 5C), rpiA::TnM (S5C Fig) or glnA::TnM mutants (S5D Fig). Importantly, polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides were detected around WT cell aggregates, but not in any of the mutants tested (Fig 5D, S5C and S5D Fig). These polysaccharides were frequently found to cover (or be adjacent to) bacterial cells, and their presence was visualized even after 6 hours post-infection (Fig 5D). Interestingly, we only observed surface openings of the epithelial barrier upon incubation with WT strains, suggesting that host cell lysis is caused by E. faecalis during the translocation process (Fig 5C and 5D and S5C and S5D Fig).

Taken together, our data reveal that E. faecalis utilizes the RpiA-GlnA-EpaX axis to generate β-1,6-linked polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides necessary for optimal migration into semisolid surfaces and for efficient paracellular translocation through human epithelial cell monolayers.

Discussion

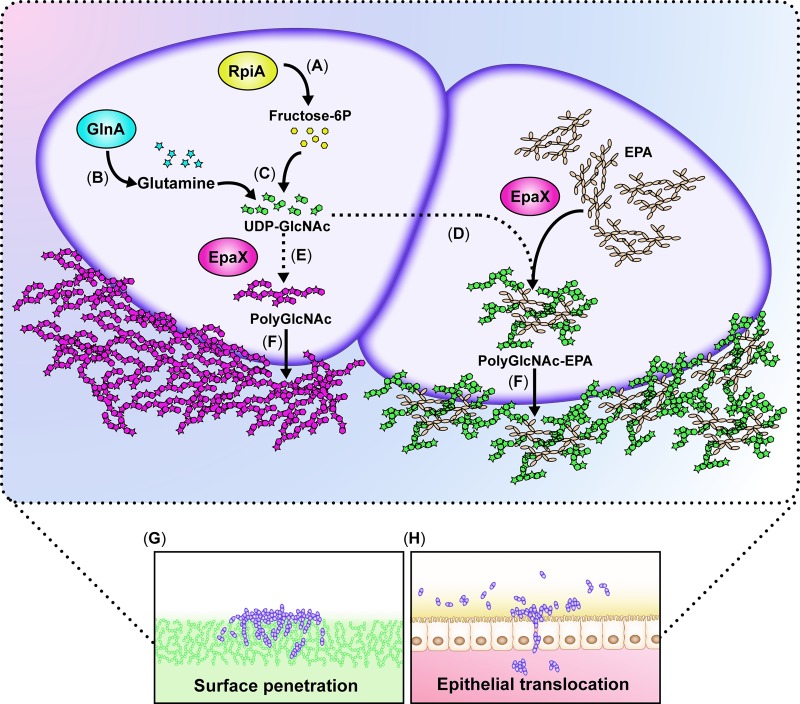

In this study, we uncovered molecular pathways and metabolic mediators that endow E. faecalis with the capacity to move into semisolid surfaces and translocate through human epithelial cell barriers (proposed model; Fig 6).

Fig 6. Proposed model for E. faecalis surface penetration using polyGlcNAc-containing polymers.

(A) RpiA is required to generate ribulose-5-phosphate, a substrate that could be converted into fructose 6-phosphate (Fructose-6P) in the non-oxidative phase of the pentose phosphate pathway. (B) GlnA generates glutamine from glutamate and ammonia. (C) Cellular fructose-6P and glutamine converge in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway to ultimately generate UDP-GlcNAc, which is used by EpaX to synthesize an enterococcal polyGlcNAc-containing polymer, which could be a decoration of the rhamnopolysaccharide EPA (D) or a yet unknown polymer (E). These polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides are extracellularly localized (F) and promote the movement and penetration of E. faecalis into semisolid surfaces (G) or through human epithelial cell monolayers (H). In the absence of a functional RpiA or GlnA, the levels of UDP-GlcNAc are not sufficient to promote polysaccharide synthesis, thus blocking efficient surface penetration and/or translocation.

Exopolysaccharides have been well characterized as prominent components of the extracellular matrices of surface-associated multicellular communities termed biofilms [51–53]. Our study reveals a new role for polyGlcNAc-containing extracellular polysaccharides as key mediators of E. faecalis migration traits. These exopolysaccharides may operate as a “glue” that holds cells together [52, 54, 55] while promoting the formation of matrix-encased multicellular aggregates during enterococcal migratory behavior. Indeed, it has been proposed that polyGlcNAc polymers facilitate intercellular adhesion by bridging electrostatic interactions between cells surfaces [56]. Alternatively, or in addition, polyGlcNAc-containing hydrated exopolysaccharides may help E. faecalis to spread in a manner similar to that found in Proteus mirabilis, which secretes polysaccharides that create a fluidic environment promoting movement on surfaces with low moisture [57]. Furthermore, in B. subtilis, a PNAG (PIA)-defective strain was shown to lose its hydrophobic or nonwetting surface characteristics [58], indicating that polyGlcNAc polymers provide a means to shape the external environment in a manner amenable to bacterial movement or penetration. Additional biophysical and chemical analyses are thus warranted to comprehensively understand how these glycopolymers promote surface penetration by E. faecalis.

Our study unearths new metabolic factors mediating enterococcal surface penetration. The first one is GlnA, which plays an essential function in the generation of glutamine [27] that is used as a constituent of proteins and a nitrogen donor for many biosynthetic reactions [59, 60]. The second factor is RpiA, which catalyzes a central enzymatic reaction in the pentose phosphate pathway that is a major route of intermediary carbohydrate metabolism. RpiA is also involved in the generation of lipopolysaccharide components in Gram-negative bacteria [28]. Our results indicate that the metabolic functions of GlnA and RpiA converge in the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway to generate the UDP-GlcNAc necessary to produce polyGlcNAc-containing polymers such as PNAG (PIA) [61]. Based on our genetic and metabolic supplementation experiments, we propose that the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway and the pentose phosphate pathway supply metabolic substrates that serve as precursors for synthesizing enterococcal polyGlcNAc-containing polymers (see proposed model, Fig 6). A link between the pentose phosphate pathway and polysaccharide synthesis was previously described in bacteria. Somerville and colleagues reported that the S. aureus transcriptional regulator RpiR, which is known to control rpiA expression, also acts as a sugar-responsive regulator that modulates polysaccharide synthesis in response to metabolite concentrations [62].

The biosynthesis of polysaccharides first occurs in the cytoplasm, and the repeating units are then assembled and exported to the surface. This process involves several key enzymes including glycosyltransferases that mobilize sugar units [63]. Our study emphasizes a major role for the putative glycosyltransferase EpaX in E. faecalis physiology, as this enzyme was pivotal for semisolid surface penetration and paracellular translocation. Supporting this concept, Rigottier-Gois and colleagues had demonstrated that EpaX is a major determinant of E. faecalis intestinal colonization in mice [46]. Of note, the penetration-defective phenotype of ΔepaX could not be complemented by exogenous GlcNAc, indicating that EpaX is required for synthesis of the polyGlcNAc structure needed for optimal surface migration. Our data also show that EpaX acts downstream of RpiA and GlnA, which explains why only the addition of exogenous PNAG (a polyGlcNAc polymer) could rescue the penetration-defective phenotype of ΔepaX strains. Consistent with the notion that GlcNAc-derived polysaccharides are necessary for semisolid surface penetration, we demonstrated that epaX mutants do not produce detectable amounts polyGlcNAc-containing exopolymers. Interestingly, bioinformatic analysis using the Protein Homology/AnalogY Recognition Engine (Phyre2) [64] indicated that EpaX has 100% similarity across its predicted secondary structure to glycosyltransferases such as N-acetylgalactosamyltransferases. Furthermore, analysis using the conserved domain architecture retrieval tool (CDART) revealed that EpaX also has similar domain architecture to YdaM, a putative glycosyltransferase shown to be required for exopolysaccharide synthesis in Bacillis subtilis [65]. However, the function of EpaX remains elusive, and its activity might have an epistatic relationship with other factors required for the production or cell surface display of polyGlcNAc-containing polymers. Recent studies proposed that epaX deletion alters the synthesis of the rhamnopolysaccharide EPA in E. faecalis by compromising the decoration of these polymers with galactose and/or GalNAc. Therefore, it was suggested that EpaX functions as a GalNAc transferase [46]. Our findings indicate that, under our conditions, the absence of EpaX in E. faecalis not only dramatically decreases the levels of GalNAc-, but also of rhamnose- and GlcNAc-containing oligosaccharides. Though rhamnose was not detected in the polysaccharides produced by ΔepaB using GC-MS analysis [6], we found that E. faecalis lacking EpaB was still able to penetrate and generate polyGlcNAc-containing polymers, suggesting that the presence of GlcNAc, but not rhamnose, in E. faecalis exopolymers is necessary for optimal penetration into semisolid surfaces. While the structure of E. faecalis EPA has not been elucidated, similar polysaccharides with branching structures composed by other oligosaccharides bound to GlcNAc or terminal β-linked GlcNAc side chains have been evidenced in other Gram-positive bacteria [66]. Indeed, our results using DspB demonstrated the presence of β-1,6 glycosidic bonds within the structure of E. faecalis polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides. However, the precise nature of the polymer involved in E. faecalis semisolid surface and epithelial barrier penetration has not yet been elucidated by purification and chemical analyses. Indeed, either EPA or another polysaccharide yet to be identified might mediate the penetration process. Future analyses to determine the structure of E. faecalis polyGlcNAc-containing exopolymers, and their link with EPA, will hence be of significant interest.

E. faecalis is a leading cause of nosocomial infections world-wide [67]. It has been shown that E. faecalis can translocate across mouse and rat intestinal tracts to reach other body sites [68, 69]. Most recently, Krueger et al. reported that after feeding mice with antibiotics, E. faecalis could be found in the liver, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes [70, 71]. PolyGlcNAc-like polysaccharides might mediate these processes by promoting enterococcal translocation across the intestinal epithelium. Interestingly, E. faecalis has been shown to form microcolonies surrounded by an extracellular matrix that not only covers the bacterial cells, but also extends into the intestinal space between cell clusters [72]. In line with our observations during semisolid surface invasion and epithelial barrier assays, Peng and collaborators described that E. faecalis formed cellular aggregates that localized with the actin cytoskeleton during the process of translocation [48]. Our findings therefore uncover that production of polyGlcNAc-containing exopolysaccharides is a mechanism that enables non-motile E. faecalis to penetrate semisolid surfaces and cross human intestinal epithelial cell monolayers.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, media and culture conditions

S3 Table describes all strains and plasmids used in this study [6, 10, 26, 32, 46, 73–83] E. faecalis was cultured overnight at 37°C in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) with 0.25% Glucose (Becton Dickinson) under shaking conditions, unless indicated otherwise. E. coli strains were cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB). Antibiotics were added to the medium when appropriate as follows: Chloramphenicol 10 μg/mL, spectinomycin 150 μg/mL or ampicillin 100 μg/mL for E. coli. Either tetracycline 15 μg/ml, chloramphenicol 10–15 μg/mL or spectinomycin 750 μg/mL for E. faecalis strains when specified. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise.

Semisolid surface penetration assay

2 μL of TSB-grown E. faecalis overnight cultures were inoculated onto modified medium optimal for lipopeptide production (MOLP) [24], containing 30 g/L peptone, 7 g/L yeast extract, 1.0 mM MgSO4, 25 μM MnSO4, 25 μM FeCl2, 0.001 mg/L CuSO4, 0.004 mg/L Na2MoO4, 0.002 mg/L KI, 5 μM ZnSO4.7H2O, 0.001 mg/L H3BO3, 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 125 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; pH 7) and 10 g/L agar (Becton Dickinson). Saline solutions were filter-sterilized independently before mixing the MOLP components. Semisolid MOLP agar was prepared the day before and air-dried (opened plates inside the biological hood) for at least 30 minutes prior to bacterial inoculation. E. faecalis MOLP-inoculated plates were incubated upside down in a highly humid environment to avoid dryness at 37°C for 6 days, unless indicated. After this period, semisolid media penetration was determined by removing all cells above the agar with 3 to 4 washes with ~10 mL distilled water and then observing bacterial growth within the agar.

When stated, MOLP media was solidified with poloxamer-407 (Sigma, Aldrich; MOLP-407), a fully autoclavable copolymer based on polyoxyethylene and polypropylene previously used for bacterial media growth development [84]. At low temperature, a poloxamer-407 solution is liquid, but becomes solid upon reaching room temperature (RT). MOLP-407 was prepared by the addition of 10 g of the polymer powder each day into 50 mL distilled water held at 4°C until a concentration of 60% [w/v] was achieved. This solution was then kept at 4°C for an extra 24 hours to ensure complete dissolution, prior to autoclaving. Next, it was cooled to RT and chilled to 4°C to liquefy. Once at low temperature, the poloxamer-407 solution was mixed 1:1 with a cold solution of 2X MOLP to a final volume of 100 mL. Subsequently, 1.5 mL of this chilled media were added into each well of 24-well plates (Falcon, Corning) and allowed to solidify at RT prior to inoculation with 1 μL of each bacterial strain grown overnight in TSB.

Quantification of agar penetration

Colony forming units (CFU) of penetrating and non-penetrating E. faecalis cells grown on MOLP (for 6 days) solidified with either 1% (w/v) agar or 30% [w/v] poloxamer-407 were measured using two distinct strategies: To determine the number of external/internal cells grown on MOLP-407, the external cells from the colonies were collected and suspended in 500 μL of saline solution (0.89% NaCl). Subsequently, the surface of the plates was washed 3–4 times with 10 mL of sterile distilled water at RT, and invading bacteria were recovered by transferring the growth from each well into media previously chilled at 4°C to sterile Eppendorf tubes. All bacterial suspensions (internal and external cells) were centrifuged at 4°C and washed 3 times with ice-cold saline solution prior to making serial dilutions and plating on TSB agar plates. After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C, the final CFU number was calculated.

To quantify invasion of E. faecalis colonies grown on MOLP with 1% agar, the colonies were grown on top of 3.0 μm filters (Whatman) to separate the external from internal cells. The first ones (external) were collected by suspending each filter and suspended them in 500 μL of 1X Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline solution (DPBS; Corning-Cellgro) and the remaining non-penetrating bacteria was removed by three washes with 10 mL of sterile distilled water and two washes with 70% ethanol (10 mL). The internal cells were recovered by removing an area of ~1 cm2 from the top layer, that was then suspended in 500 μL of DPBS as previously described above. Penetrating and non-penetrating bacterial suspensions were homogenized with a mortar and pestle followed a passage through a needle (27-gauge) syringe and filtered with a 40 μm nylon filter (BD Falcon). Final saline suspensions (1 mL) were sonicated for 2 minutes (30 seconds ON and OFF cycles) at 30% amplitude (Sonics Vibra Cell) to separate cellular clumps and then they were serially diluted and CFUs were determined as described above. Only when mutants exhibited growth differences to their parental strain, the final CFUs/mL was normalized to the absorbance (OD600) of each saline suspension from which serial dilutions were performed (Normalized CFUs/mL).

Flow cytometry analyses

Internal and external cells of MOLP-grown colonies were recovered and processed as described above (see agar-penetration quantification section). Each penetrating and non-penetrating population was then diluted down to 0.5 OD600 prior to be stained with Brilliant Violet-570 (BV-570; LIVE/DEAD staining kit—Life technologies) for 30 min at RT in the dark, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were washed twice with 1 mL DPBS and subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (BioWorld) overnight at 4°C. Heat killed (100°C for 24 hours) TSB-grown E. faecalis was used as dead control. Live and dead bacteria were analyzed using a BD LSRII Flow cytometer.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

E. faecalis colonies were grown on MOLP as described above. SEM samples were prepared as previously described [85], with some minor modifications: External cells grown on MOLP were carefully transferred to ∼10 mm diameter pieces of 0.1% poly-L-lysine (Sigma, Aldrich) pre-treated Silicon wafers (Ted Pella). Samples were then fixed in a solution with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1% DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide), 0.15% alcian blue and 0.15% safranin O [86], at RT for 18 hours. When stated, a 90 min post-fixation step with 1% Osmium tetroxide was performed. After three 15 min washes with distilled water and dehydration through a graded series of ethanol, the samples, unless specified were infiltrated with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS; Sigma, Aldrich), through one incubation in 50% HMDS (in 100% ethanol) at RT for 1 hour and then two in 100% HMDS for 30 min. At this point the PDMS-bound samples were mounted on pins, dried under vacuum overnight, sputter-coated with gold–palladium alloy, and examined by SEM. For analyzing invading bacteria, small agar sections were placed on the silicon chips after removing the external cells with water; and treated as described above.

In order to objectively quantify the fraction of cells covered in matrix, the SEM images were analyzed using automatic image analysis software, Ilastik 1.3.0 [87]. The software was first trained to recognize different image structures, including background, matrix and cells, based on a single SEM image only. In this training stage, we manually identified regions in the image corresponding to background, matrix and cells, which the software uses to update a machine learning algorithm. After training, the algorithm was used to automatically analyze all remaining SEM images. In those images, pixels corresponding to either matrix or cells are automatically detected, thereby providing an estimate for fraction of cell surface that is covered in matrix. In all cases, we analyzed the SEM images at the same 20,000 X magnification. This magnification was chosen such that we could examine as much surface as possible, without compromising on the resolution needed for automatic image analysis.

Genetic screening of mutants

A Mariner transposon insertion library in the multidrug resistant clinical isolate MMH594 [88] was constructed. E. faecalis was transformed with mariner delivery system pLB02 (kind gift of Dr. Lynn E. Hancock), which is identical to progenitor pCAM45 [89], except that erythromycin and kanamycin resistance markers were swapped for tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance, respectively. Essentially as described in previous studies [89],, transformants were initially selected at 30°C and the cure of the delivery vector was done at elevated temperature with selection for only the chloramphenicol resistance harbored by the transposon. A total of >300,000 MMH594 colonies possessing mariner insertions were collected as a pool.

To find targets necessary for enterococcal semisolid surface penetration, a replica-plating method was used. Approximately 6,000 mariner transposon mutants grown on TSB in 96-well plates for 24 hours were replica plated onto MOLP plates to screen for agar penetration capacity. A non-penetrating phenotype was designated as the ability to form WT-like colonies without growth inside the semisolid surface. To determine the genome site insertion of the mariner transposon, we used a previously described modified arbitrary PCR method with few modifications [90]. Amplification of short DNA-fragments was performed by using Platinum PCR High Fidelity SuperMix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described by the manufacturer. External and internal oligonucleotides specific for the Tn-Mariner (TnMextF1,and TnMxtF2; S4 Table) and the arbitrary primers (STAPHarb1, STAPHarb2, and STAPHarb3)[90] were utilized for the PCR reactions. The first round was performed using the arbitrary primers STAPHarb1 and SATPHarb2 (0.6 μM) paired with TnMexF1 (0.3 μM). 5.0 μL of a lysate of each mutant colonies obtained as previously described [91] was used for the PCR reaction: 95°C for 3 minutes; five cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 30°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 1 min; then 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 52°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 1 minute; and finally 72°C for 5 minutes. Samples were kept at 4°C. The second PCR round was performed with primers TnMextF2 (0.3 μM) and STAPHarb3 (0.6 μM) as follow: 3 minutes at 94°C, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by 72°C for 5 minutes. The samples were then kept at 4°C. The PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the second round PCRs containing at least one distinct visible fragment were used for further characterization. Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed with TnMextF2 primer. To identify of the Tn-Mariner insertion sites, a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) was used.

Plasmid construction and genetic complementation

The mariner transposon mutants, glnA::TnM and rpiA::TnM, were complemented in-trans by inserting the corresponding WT gene in the pAT28 plasmid [82]. To this end, PCR-amplified gene products with their corresponding promoters were generated for rpiA and glnRA from purified MMH594 genomic DNA. For glnRA, we used primers JD15 and JD30 (for sequences see S4 Table) to amplify a fragment of 2248 bp, which included a region 388 bp upstream of glnR, as well as glnR and glnA open reading frames (ORF). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI (NEB) and ligated into pAT28 to generate the complementation vector pJR01. Likewise, rpiA amplification was done using primers HV172 and HV173 (S4 Table). The amplified product (1291 bp) was digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated into pAT28 to generate the complementation vector pAH01. Plasmids, pJR01 and pAH01, were electroporated in E. coli and after sequencing several colonies; one was selected for complementation of each transposon mutant. The complementation vectors were transformed by electroporation into the corresponding E. faecalis strains and recovered on TSB plates (750 μg/mL spectinomycin) as previously described [78].

The fluorescence reporter strains were constructed by conjugation of the vector pV158-GFP between the donor E. faecalis OG1RF and the recipient MMH594 rpiA::TnM and glnA::TnM strains, as previously reported [92]. Briefly, TSB-grown overnight cultures of donor (15 μg/mL tetracycline) and recipients (10 μg/mL chloramphenicol) were diluted down to 0.05 OD600 and allowed to reach and absorbance of O.5 OD600. Then, the donor and recipient were mixed 1:10, 10:1 and 1:1 prior to concentrating these solutions to a final volume of 50 μL. Each one was finally placed onto a 0.2 μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane (13 mm; Nucleopore) previously placed on TSB agar plates. After 24 hours at 37°C, filters were removed from the plates and placed in 1 ml 1X PBS (Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline; Sigma, Aldrich). Cells suspensions were then diluted and 10−3, 10−7 and 10−9 dilutions were plated on TSB agar with 15 μg/mL tetracycline, 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol and 250 μg/mL gentamycin. After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C, GFP fluorescent colonies were selected by microscopic analysis. The vector pV158-GFP was electroporated into electrocompetent cells of E. faecalis WT and ΔepaX strains prepared as previously described [93]. Cells were allowed to recover for 2 hours in 1 mL of SGM17MC recovery medium [93] before being plated and selected on TSB agar as described above.

Generation of deletion mutants

E. faecalis MMH594 was used for the generation of the EF2170 (V583 epaX homolog) deletion mutant by allelic exchange (ef2170::spcR) using the pMINIMAD thermosensitive plasmid [81]. Briefly, fragments upstream and downstream of the EF2170 gene were PCR amplified with Phusion polymerase (NEB) using JD1, JD3; and JD6, JD8 primers, respectively. The spectinomycin resistance gene spcR was amplified from vector pIC333 [79] with primers JD4 and JD5. These three purified PCR fragments were assembled with Gibson Assembly Mix 2X (NEB) following the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. The final reaction was then used as template for amplifying a ~3 kb product (using primers JD2 and JD7) that was inserted into the BamHI site of pMINIMAD generating the vector pJR02. This plasmid was then modified by inserting in the SalI site, the chloramphenicol resistance gene cat, amplified from pLT06 [10] with primers JD44 and JD45 (S4 Table) generating pJR03. This last vector was then transformed into E. coli Top10 and transformants were selected after growth overnight in LB broth with 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol at 37°C. The plasmid pJR03 was purified and electroporated into WT MMH594 as previously described [78]. Transformed bacteria were grown on Todd-Hewitt agar plates with 15 μg/mL chloramphenicol at RT. Next, positive colonies were grown overnight on TSB with chloramphenicol at RT. Cells were centrifuged, suspended in 200 μl of fresh media, and plated in TSB agar with 400 μg/mL of spectinomycin. After 48 hours at 42°C, candidate colonies were grown on TSB agar with either 400 μg/mL of spectinomycin or 15 μg/mL chloramphenicol at RT. Allelic exchange was confirmed by PCR for the spectinomycin resistant and chloramphenicol sensitive colonies.

Polysaccharide purification and analyses

Bacterial strains were cultured in 500 mL of either MOLP broth under static conditions to an OD600 of 0.6 or MOLP agar for 6 days at 37°C. Polysaccharides were extracted as previously described [46, 94] with minor modifications. Briefly, cells from either liquid cultures (for glycosyl composition analysis) or colonies were centrifuged 20 minutes at 4000 rpm and washed with 10 mL of sucrose-buffer (25% sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl; pH 8). Pellets were then suspended in 15 mL sucrose-buffer supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme (Thermo Scientific) and 10 U/mL mutanolysin and incubated at 37°C overnight with gentle agitation. Following this incubation, the cellular fraction was removed by centrifugation for 20 minutes at 4500 rpm. The supernatants were treated with 200 μg/mL RNase A, 200 μg/mL DNase, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2 at 37°C for 8h to remove nucleic acids. Protein impurities were removed by adding proteinase K (50 μg/mL) to each supernatant and incubating them at 42°C overnight. Remaining contaminants were extracted using 1 mL of chloroform. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube following centrifugation (4500 rpm) for 15 minutes. Polysaccharides were precipitated by adding ethanol to a final concentration of 75% and incubation at − 80°C for 30 minutes, followed by a centrifugation (4500 rpm for 1 hour) at 4°C. Precipitated pellets were washed using 75% ethanol and allowed to air dry. Cell wall polysaccharide samples were submitted for glycosyl composition analysis to the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center (University of Georgia). Glycosyl composition analyses were performed using GC-MS of the per-O-trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatives of the monosaccharide methyl glycosides. The TMS derivatives were produced from the sample by acidic methanolysis [95]. GC-MS analysis of TMS methyl glycosides was done on an Agilent 7890A GC interfaced to a 5975C MSD, using an Supelco Equity-1 fused silica capillary column (30 m x 0.25 mm ID). A total of 3 independent biological samples per strain were analyzed.

To visually analyze the composition of polysaccharides extracted from non-penetrating cells of E. faecalis VE14089 WT, ΔepaX and ΔepaX p-epaX, dry samples were suspended in 100 mL of Tris–NaCl (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl; pH 8.0) and mixed with 16% glycerol prior to be run (25 μL) on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide to bisacrylamide, 29:1; Fisher Scientific) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (89 mM Tris base, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) for 90 minutes at 130 volts. Detection of polysaccharides was made with silver staining as previously described [46] with minor modifications. Briefly, the polyacrylamide gel was washed once with distilled water and incubated 45 minutes with 1 mg/mL of alcian blue in 3% acetic acid. Later, after three washes with distilled water, the gel was incubated in a solution with 3.4 mM K2Cr2O7 and 3.2 mM HNO3 for 7 minutes and then washed with water as described above. Following these steps, the gel was then treated with 12mM AgNO3 and exposed to intense light for 30 min. It was later washed with water, soaked in 50 mL of 0.28 M Na2CO3 and 6mM formaldehyde until signal was visually detected and transferred to a solution of 0.1 M acetic acid for storage.

Immunochemical detection of polyGlcNAc-containing polysaccharides

Bacterial samples from either external or penetrating E. faecalis grown on MOLP for 6 days were collected and processed as previously described [8], with the following modification: Cells were suspended in 1000 μL of DPBS and then spotted onto microscope slides. After samples air-dried, they were fixed by methanol: acetone 1:1 for 10 min at -20°C. Then, they were treated with 100% ice-cold methanol for ~1 min, followed by 3 washes with PBS-NaCl buffer (20 mM PBS and 150 mM NaCl). Samples were blocked with 2.5% Normal Horse serum (Vectors Lab) for 45 min at RT. PBS-1% BSA (bovine serum albumin; Sigma, Aldrich) was then added after removing the blocking serum. After 1 min incubation at RT, slides were reacted overnight at 4°C with 20 μg/mL of human IgG mAb F598, which specifically binds to β-1,6-linked GlcNAc polysaccharides [8, 52]. After 3 washes with PBS-NaCl, samples were reacted with the secondary antibody, anti-human IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor-488 (15 μg/mL; Invitrogen) and DAPI (2.0 μg/mL), for 2 hours at RT. To visualize GlcNAc residues, samples were incubated with 5 μg/mL of the lectin WGA (wheat germ agglutinin) directly conjugated to Texas Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at RT. Slides were then washed and cover-slipped using Fluoromount-G media (SouthernBiotech). Images were captured at 63x magnification at 1000 ms for DAPI, and 600–1500 ms for FITC and Rhodamine. Imaging was performed with a Zeiss AxioObserver inverted wide field/fluorescence microscope and processed using MetaMorph software. All images were adjusted to reduce background fluorescence.

For enzymatic treatments, cell samples obtained as described above were diluted 1:10 in PBS. 10 μL of these cell solutions were suspended in 90 μL of Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4) containing 300 μg/mL DspB [96]. Samples were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with constant shaking, and then centrifuged to suspend the pelleted cells into 50 μL of fresh TBS. Each suspension was subsequently placed onto glass slides to then be treated as described above.

Colony immunoblotting assay

E. faecalis colonies were analyzed for extracellular production of polyGlcNAc-polymers using a protocol previously described [97] with some modifications: Briefly, 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) were placed on 1-day-old colonies grown on MOLP until they became completely wet. The plates/membranes were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes prior to be carefully removed and transfer colony side up to a glass petri dish for air-drying (10 minutes at 37°C). Following this step, the air-dried membranes were immersed in chloroform at RT for ~15 minutes or until the chloroform completely evaporated. Each nitrocellulose membrane was incubated colony side down for 60 minutes in the blocking buffer (25mM Tris-base, 0.15M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20, 5% non-fat milk). After 3 washes, 5 minutes each with TBS-T (25mM Tris-base, 0.15M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20), the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation in TBS-T with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 200 μg/mL of the primary antibody mAb F598. Membranes were washed with TBS-T as described above and then incubated for 60 minutes in TBS-T containing a 1/10000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG polyclonal antiserum (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were then washed 3 times for 5 min each with TSB-T and were developed using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemioluminescent Substrate Kit as directed by manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Nanostring analysis of E. faecalis glycosyltransferases

External and penetrating cells, from 2-day-old colonies grown on MOLP were collected and suspended in 2 mL of cold RNAlater. Samples were pelleted and supernatant was discharged prior to storage at -80°C. For cell lysis, these pellets were suspended in RLT buffer (500 μL; Qiagen) and completely disrupted with a beat beater in one volume 0.5 mm zilica/sirconia beads for ~4 minutes (4 times × 60 seconds). Cellular debris were removed and supernatants were then subjected to probe hybridization and processing with the Nanostring nCounter Prep Station and Digital Analyzer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw code counts were analyzed according to manufacturer’s guidelines; briefly, total transcript counts were normalized using internal controls with background subtraction. Transcript counts for 5 genes (gyrB, def, sigA, aqpZ and folB) were used for geometric mean normalization to correct for differences in total mRNA concentration. All data were collected from 2 biological replicates and gene expression was considered significantly altered if the transcript number changed >2-fold. Total counts were expressed as log2-change relative to the counts of non-penetrating cells at day 1, a time point where invasion was not evidenced in MOLP.

Translocation assays

T84 human intestinal epithelial cells (Sigma, Aldrich) were grown and maintained as previously described [49] with some modifications. Briefly, cell monolayers were grown on plastic in a 1:1 Dubelcco’s Modified Eagle’s medium and nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Corning Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta biologicals), 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium piruvate, 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7), 1X non-essential amino acids, 50 units/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Corning Inc.), 5 μg/mL prophylactic plasmocin (InvivoGen), and 0.007% β-mecaptoethanol (Sigma, Aldrich). When monolayers reached confluence or near-confluence, cells were detached and split as previously described [98]. Translocation was performed by seeding 105 T84 human epithelial cells from previous passages into a 24-well Transwell system with 3.0-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membranes (Corning Costar Corp). This pore size allows bacteria, but not T84 cells, to penetrate the membrane. A volume of 300 and 1000 μL of the tissue culture medium described above was added to the apical and basolateral chambers, respectively; and this medium was changed every 2–3 days. The developing progress of T84 tight junctions was monitored by Millicell-ERS-2 measurement (Millipore). Translocation experiments were performed after 8 days of culture, when the trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TER) of T84 monolayers reached ~8000 Ω/cm2 or higher. To prepare bacteria for translocation, 12-hours-bacterial cultures (with appropriate media and antibiotics) were diluted down in HBSS (Hanks balanced salt solution without Ca2+ and Mg2+; Corning Inc.) to an absorbance of 0.25 OD600 (~108 CFU/mL). Bacterial solutions were then washed twice with 1 mL of HBSS and finally suspended in Translocation Media (TM; Gibco): Advanced DMEM/F-12 mixture supplemented with 5% FBS, 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7), 0.007% β-mecaptoethanol and when specified, 2 mM GluN. Prior to bacterial inoculation, the filters were washed twice with TM. After this step, 1000 μL of fresh medium were added to the basolateral chamber, and 300 μL of each TM-suspended bacterial culture prepared as described above, were inoculated to the apical side of the chamber; this inoculum is consistent with that used by others [49] and with the density of intestinal enterococci in some settings. TER was monitored at the beginning and after 8 hours post-infection. The TER values remained similar to those obtained for the pre-infected monolayers, indicating that the integrity of cell barriers was conserved throughout the experiments. CFUs of viable bacteria in both chambers were counted at 0, and 8 hours by removing 20 μl aliquots, serially diluting and plating on TSB agar plates. For each strain, 8–9 independent transwells were used and the experiments were repeated at least three times.

To visualize translocating bacteria, filters seeded with polarized human enterocyte-like T84 cells as described above were infected for 2-hours with E. faecalis constitutively expressing GFP, and then samples (infected and uninfected) were stained and observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy. Bacteria and epithelial cell translocation assays were done in TM supplemented with 15 μg/mL tetracycline. For immunofluorescence staining, medium on each transwell was removed and filters were washed two times with pre-warmed (37°C) PBS. Cells were then fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 40 min. Following fixation, cells were washed with DPBS for 30 seconds, and permeabilized by incubating them with PBT (PBS and 0.5% TritonX-100) solution for 15 minutes. The solution was removed and the cells (transwells) were washed twice with DPBS for 30 seconds. After this, samples were blocked with PBS-1% BSA for 1 hour at RT, and then washed once with PBS as previously described. Cells were reacted overnight at 4°C with 20 μg/mL of MAb F598 [8, 52]. After three washes with PBS (5 minutes) samples were incubated with the secondary antibody, goat anti-human IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor-647 (15 μg/mL; Invitrogen) for 2 hours at RT. Thereafter, cells were washed three times with PBS (5 minutes), followed by incubation with cellular dyes (200nM of both Alexa Fluor 594-coupled phalloidin and DAPI; Invitrogen) in PBS containing for 30 min in the dark at RT. The solution was removed and samples were washed three times with PBS for 30 seconds. Filters were cut and transferred into ~10 μL of ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher), followed by sealing on glass slides and storing in the dark at 4°C until microscopy. Imaging was performed with a LSM880 confocal microscope and processed using Image J software. All images were adjusted to reduce background fluorescence.

Statistical analyses

Unless noted otherwise, all experiments were repeated at least three times and results were similar between repeats. All statistical analyses were determined using GraphPad Prism 7.0. Differences between the means of experimental groups were calculated using either a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Error bars represent SEM from independent samples assayed within the represented experiments. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supporting information

Strain MMH594 (unless specified otherwise) was grown on MOLP solidified with either 1% agar (A, B and E), agarose (C) or 30% poloxamer-407 (MOLP-407; D) for 6 days at 37°C. Enterococcal penetration was evidenced as a colony-print inside the agar after removing the external cells. (A) Colonies (outside) and bacterial penetration areas (inside) of E. faecalis clinical isolates V583, JH2-2, 12030, MMH594 and VE14089, and the human commensal OG1RF. (B) Time-lapse analysis of E. faecalis generating colony-prints over a period of 144 hours (6 days). Scale bars A and B: 6,000 μm. (C) External or penetrating E. faecalis cells (on MOLP with agarose concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1.0%. Lower scale bar: 5,000 μm. (D) External (outside) and internal (inside) E. faecalis cells grown on MOLP-407 (top) were determined by plating bacterial serial dilutions on TSB agar plates and by quantifying colony forming units (CFUs/mL) after 24 hours of growth (bottom; mean±SE; n = 4; *P<0.05; two-tailed unpaired t-test). Scale bar: 2,000 μm. Transmitted light images of agar sections from the center (E) or edge (F) areas of the penetrating colony-print. Top white bar indicates the beginning of the agar in each section. Lower scale bar: 60 μm. Yellow lines indicate places where the depth of the microcolony was measured.

(PDF)