Abstract

Data analysis is one of the most important, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. Through rigorous analysis, data can illuminate the complexity of human behavior, inform interventions, and give voice to people’s lived experiences. While significant progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, the process often remains nebulous. To better understand how our field conducts and reports qualitative analysis, we reviewed qualitative papers published in Health Education & Behavior between 2000–2015. Two independent reviewers abstracted information in the following categories: data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. Of the forty-eight (n=48) articles identified, the majority (n=31) reported using qualitative software to manage data. Double-coding transcripts was the most common coding method (n=23); however, nearly one-third of articles did not clearly describe the coding approach. Although terminology used to describe the analytic process varied widely, we identified four overarching trajectories common to most articles (n=37). Trajectories differed in their use of inductive and deductive coding approaches, formal coding templates, and rounds or levels of coding. Trajectories culminated in the iterative review of coded data to identify emergent themes. Few papers explicitly discussed trustworthiness or reflexivity. Member checks (n=9), triangulation of methods (n=8), and peer debriefing (n=7) were the most common. Variation in the type and depth of information provided poses challenges to assessing quality and enabling replication. Greater transparency and more intentional application of diverse analytic methods can advance the rigor and impact of qualitative research in our field.

Keywords: health behavior, health promotion, qualitative methods, research design, training health professionals

Introduction

Data analysis is one of the most powerful, yet least understood stages of the qualitative research process. During this phase extensive fieldwork and illustrative data are transformed into substantive and actionable conclusions. In the field of health education and health behavior, rigorous data analysis can elucidate the complexity of human behavior, facilitate the development and implementation of impactful programs and interventions, and give voice to the lived experiences of inequity. While tremendous progress has been made in advancing the rigor of qualitative analysis, persistent misconceptions that such methods can be intuited rather than intentionally applied, coupled with inconsistent and vague reporting, continue to obscure the process (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014). In an era of public health grounded in evidence-based research and practice, rigorously conducting, documenting, and reporting qualitative analysis is critical for the generation of reliable and actionable knowledge.

There is no single “right” way to engage in qualitative analysis (Saldana & Omasta, 2018). The guiding inquiry framework, research questions, participants, context, and type of data collected should all inform the choice of analytic method (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Saldana & Omasta, 2018). While the diversity and flexibility of methods for analysis may put the qualitative researcher in a more innovative position than their quantitative counterparts (Miles et al., 2014), it also makes rigorous application and transparent reporting even more important (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2011). Unlike many forms of quantitative analysis, qualitative analytic methods are far less likely to have standardized, widely agreed upon definitions and procedures (Miles et al., 2014). The phrase thematic analysis, for example, may capture a variety of approaches and methodological tools, limiting the reader’s ability to accurately assess the rigor and credibility of the research. An explicit description of how data were condensed, patterns identified, and interpretations substantiated is likely of much greater use in assessing quality and facilitating replication. Yet, despite increased attention to the systematization of qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2018; O’Brien et al., 2014; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007), many studies remain vague in their reporting of how the researcher moved from “1,000 pages of field notes to the final conclusions” (Miles et al., 2014).

Reflecting on the relevance of qualitative methods to the field of health education and health behavior, and challenges still facing the paradigm, we were interested in understanding how our field conducts and reports qualitative data analysis. In a companion paper (Kegler et al. 2018), we describe our wider review of qualitative articles published in Health Education & Behavior (HE&B) from 2000 to 2015, broadly focused on how qualitative inquiry frameworks inform study design and study implementation. Upon conducting our initial review, we discovered that our method for abstracting information related to data analysis—documenting the labels researchers applied to analytic methods—shed little light on the concrete details of their analytic processes. As a result, we conducted a second round of review focused on how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. In particular, we assessed data preparation and management, approaches to data coding, analytic trajectories, methods for assessing credibility and trustworthiness, and approaches to reflexivity. Our objective was to develop a greater understanding of how our field engages in qualitative data analysis, and identify opportunities for strengthening our collective methodological toolbox.

Methods

Our methods are described in detail in a companion paper (Kegler et al. 2018). Briefly, eligible articles were published in HE&B between 2000 and 2015 and used qualitative research methods. We excluded mixed methods studies because of differences in underlying paradigms, study design, and methods for analysis and interpretation. We reviewed 48 papers using an abstraction form designed to assess 10 main topics: qualitative inquiry framework, sampling strategy, data collection methods, data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, reporting of results, use of theory, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity. The present paper reports results on data management software, coding approach, analytic approach, indicators of trustworthiness, and reflexivity.

Each article was initially double-coded by a team of six researchers, with one member of each coding pair reviewing the completed abstraction forms and noting discrepancies. This coder fixed discrepancies that could be easily resolved by re-reviewing the full text (e.g. sample size); a third coder reviewed more challenging discrepancies, which were then discussed with a member of the coding pair until consensus was reached. Data were entered into an Access database, and queries were generated to summarize results for each topic. Preliminary results were shared with all co-authors for review, and then discussed as a group.

New topics of interest emerged from the first round of review regarding how analytic approaches and techniques were applied. Two of the authors conducted a second round of review focused on: use of software, how authors discussed achieving coding consensus, use of matrices, analytic references cited, variation in how authors used the terms code and theme, and identification of common analytic trajectories, including how themes were identified, and the process of grouping themes or concepts. To facilitate the second round of review, the analysis section of each article was excerpted into a single document. One reviewer populated a spreadsheet with text from each article pertinent to the aforementioned categories, and summarized the content within each category. These results informed the development of a formal abstraction form. Two reviewers independently completed an abstraction form for each article’s analysis section and met to resolve discrepancies. For three of the categories (use of the terms code and theme; how themes were identified; and the process of grouping themes or concepts), we do not report counts or percentages because the level of detail provided was often insufficient to determine with certainty whether a particular strategy or combination of strategies was used.

Results

Data preparation and management

We examined several dimensions of the data preparation and management process (Table 1). The vast majority of papers (87.5%) used verbatim transcripts as the primary data source. Most others used detailed written summaries of interviews or a combination of transcripts and written summaries (14.6%). We documented whether qualitative software was mentioned and which packages were most commonly used. Fourteen of the articles used Atlas.ti (29.2%) and another seventeen (35.4%) did not report using software. NVivo and its predecessor NUD-IST were somewhat common (20.8%), and Ethnograph was used in two articles. Several other software packages were mentioned in one of the papers (e.g. AnSWR, EthnoNotes). Of those reporting use of a software package, the most common use, in addition to the implied management of data, was to code transcripts (33.3%). Approximately 10.4% described using the software to generate code reports, and 8.3% described using the software to calculate inter-rater reliability. Two articles (4.2%) described using the software to draft memos or data summaries. The remainder did not provide detail on how the software was used (16.7%).

Table 1.

Approaches to data preparation and management in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

| N | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of raw data analyzed | ||

| Verbatim transcripts | 42 | 87.5 |

| Detailed written summaries | 7 | 14.6 |

| Other | 2 | 4.2 |

| Qualitative software used | ||

| Atlas.ti | 14 | 29.2 |

| NVivo | 10 | 20.8 |

| Ethnograph | 2 | 4.2 |

| MAXQDA | 0 | 0.0 |

| DeDoose | 0 | 0.0 |

| Not specified | 17 | 35.4 |

| Other | 5 | 10.4 |

| How software was used | ||

| Code transcripts | 16 | 33.3 |

| Generate code reports | 5 | 10.4 |

| Calculate interrater reliability | 4 | 8.3 |

| Draft memos/summaries | 2 | 4.2 |

| No details | 8 | 16.7 |

| No software package specified | 17 | 35.4 |

| Other | 4 | 8.3 |

Note. Percentages may sum to >100 due to the use of multiple approaches

Data coding and analysis

Coding and consensus

Double coding of all transcripts was most common by far (47.9%), although a significant proportion of papers did not discuss their approach to coding or the description provided was unclear (31.3%) (Table 2). Among the remaining papers, approaches included a single coder with a second analyst reviewing the codes (8.3%), a single coder only (6.3%), and double coding of a portion of the transcripts with single coding of the rest (6.3%). A related issue is how consensus was achieved among coders. Approximately two-thirds (64.6%) of articles discussed their process for reaching consensus. Most described reaching consensus on definitions of codes or coding of text units through discussions (43.8%), while some mentioned the use of an additional reviewer to resolve discrepancies (8.3%).

Table 2.

Approaches to data coding and analysis in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

| Coding approach | ||

|---|---|---|

| Double coding of all transcripts | 23 | 47.9 |

| Single coder with reviewer | 4 | 8.3 |

| Double coding of a portion of the transcripts | 3 | 6.3 |

| Single coder | 3 | 6.3 |

| Not discussed or unclear | 15 | 31.3 |

| How consensus was reached | ||

| Through discussion | 21 | 43.8 |

| Additional reviewer to resolve discrepancies | 4 | 8.3 |

| Process not discussed | 17 | 35.4 |

| Other | 8 | 16.7 |

| Use of matrices | ||

| To compare codes/themes across cases or groups | 7 | 14.6 |

| Not used | 38 | 79.2 |

| Other | 4 | 8.3 |

| Analytic trajectories | ||

| Pathway 1 | 7 | 14.6 |

| Pathway 2 | 9 | 18.8 |

| Pathway 3 | 16 | 33.3 |

| Pathway 4 | 5 | 10.4 |

| Other | 5 | 10.4 |

| Not enough detail | 6 | 12.5 |

Note. Percentages may sum to >100 due to the use of multiple approaches

Analytic approaches named by authors

As reported in our companion paper, thematic analysis (22.9%), content analysis (20.8%), and grounded theory (16.7%) were most commonly named analytic approaches. Approximately 43.8% named an approach that was not reported by other authors, including inductive analysis, immersion/crystallization, issue focused analysis, and editing qualitative methodology. Approximately 20% of the articles reported using matrices during analysis; most described using them to compare codes or themes across cases or demographic groups (14.6%).

We also examined which references authors cited to support their analytic approach. Although editions varied over time, the most commonly cited references included: Miles and Huberman (1984, 1994); Bernard (1994, 2002, 2005), Bernard & Ryan (2010), or Ryan & Bernard (2000, 2003); Patton (1987, 1990, 1999, 2002); and Strauss & Corbin (1994, 1998) or Corbin & Strauss (1990). These authors were cited in over five papers. Other references cited in 3–5 papers included: Lincoln and Guba (1985) or Guba (1978); Krueger (1994, 1998) or Krueger & Casey (2000); Creswell (1998, 2003, 2007); and Charmaz (2000, 2006).

Terminology: codes and themes

Given the diversity of definitions for the terms code and theme in the qualitative literature, we were interested in exploring how authors applied and distinguished the terms in their analyses. In over half of the articles, either both terms were not used, or the level of detail provided did not allow for clear categorization of how they were used. In the remainder of articles, we observed two general patterns: 1) the terms being used interchangeably and 2) themes emerging from codes.

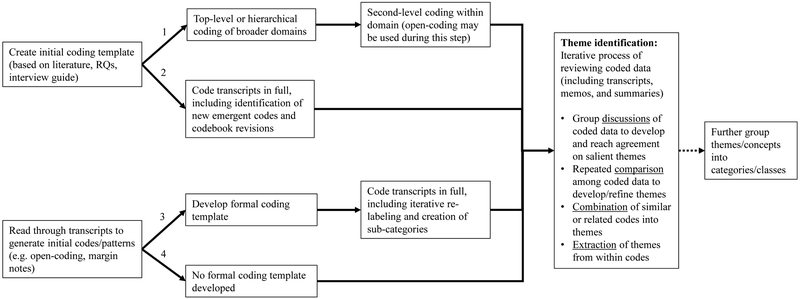

Common analytic trajectories

In addition to examining various aspects of the analytic process as outlined above, we attempted to identify common overarching analytic trajectories or pathways. Authors generally used two approaches to indexing or breaking down and labeling the data (i.e., coding). The first approach (Pathways 1 and 2) was to create an initial list of codes based on theory, the literature, research questions, or the interview guide. The second approach (Pathways 3 and 4) was to read through transcripts to generate initial codes or patterns inductively. This approach was often labeled ‘open-coding’ or described as ‘making margin notes’ or ‘memoing’. We were unable to categorize 11 articles (22.9%) into one of the above pathways because the analysis followed a different trajectory (10.4%) or there was not enough detail reported (12.5%).

Those studies that began with initial or ‘start codes’ generally followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 1; 14.6%) was to code the data using the initial codes and then conduct a second round of coding within the ‘top level’ codes, often using open-coding to allow for identification of emergent themes. The second (Pathway 2; 18.8%) was to fully code the transcripts with the initial codes while simultaneously identifying emerging codes and modifying code definitions as needed. Those that did not start with an initial list of codes similarly followed two pathways. The first (Pathway 3; 33.3%) was to develop a formal coding template after open-coding (e.g., code transcripts in full with an iterative relabeling and creation of sub-codes) and the second (Pathway 4; 10.4%) was to use the initial codes generated from inductively reading the transcripts as the primary analytic step.

From all pathways, several approaches were used to identify themes: group discussions of salient themes, comparisons of coded data to develop or refine themes, combining related codes into themes, or extracting themes from codes. A small number of articles discussed or implied that themes or concepts were further grouped into broader categories or classes. However, the limited details provided by the authors made it difficult to ascertain the process used.

Validity, Trustworthiness, and Credibility

Few papers explicitly discussed techniques used to strengthen validity (Table 3). Maxwell (1996) defines qualitative validity as “the correctness or credibility of a description, conclusion, explanation, interpretation, or other sort of account.” Member checks (18.8%; soliciting feedback on the credibility of the findings from members of the group from whom data were collected (Creswell & Poth, 2018)) and triangulation of methods (16.7%; assessing the consistency of findings across different data collection methods (Patton, 2015)) were the techniques reported most commonly. Peer debriefing (14.6%; external review of findings by a person familiar with the topic of study (Creswell & Poth, 2018)), prolonged engagement at a research site (10.4%), and analyst triangulation (10.4%; using multiple analysts to review and interpret findings (Patton, 2015)) were also reported. Triangulation of sources (assessing the consistency of findings across data sources within the same method (Patton, 2015)), audit trails (maintaining records of all steps taken throughout the research process to enable external auditing (Creswell & Poth, 2018)), and analysis of negative cases (examining cases that contradict or do not support emergent patterns and refining interpretations accordingly (Creswell & Poth, 2018)) were each mentioned only a few times. Lack of generalizability was discussed frequently, and was often a focus of the limitations section. Another commonly discussed threat to validity was an inability to draw conclusions about a construct or a domain of a construct because the sample was not diverse enough or because the number of participants in particular subgroups was too small. No papers discussed limitations to the completeness and accuracy of the data.

Table 3.

Approaches to establishing credibility, trustworthiness, and reflexivity in qualitative papers, Health Education & Behavior 2000-2015 (n=48)

| Credibility and Trustworthiness | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triangulation of methods | 8 | 16.7 |

| Member checks | 9 | 18.8 |

| Peer debriefing | 7 | 14.6 |

| Prolonged engagement at research site | 5 | 10.4 |

| Analyst triangulation | 5 | 10.4 |

| Triangulation of sources | 3 | 6.3 |

| Audit trail | 3 | 6.3 |

| Analysis of negative cases | 3 | 6.3 |

| Other | 6 | 12.5 |

| Reflexivity | ||

| Described characteristics of study team members | ||

| Yes, fully | 4 | 8.3 |

| Yes, minimally | 30 | 62.5 |

| No | 14 | 29.2 |

| Reflections on impact of relationships and extent of interaction on research | ||

| Yes | 6 | 12.5 |

| No | 42 | 87.5 |

| Reflections on reflexivity, positionality, personal bias | ||

| Yes | 2 | 4.2 |

| No | 46 | 95.8 |

Note. Percentages may sum to >100 due to the use of multiple approaches

Reflexivity

Reflexivity relates to the recognition that the perspective and position of the researcher shapes every step of the research process (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Patton, 2015). Of the papers we reviewed, only four (8.3%) fully described the personal characteristics of the interviewers/facilitators (e.g. gender, occupation, training; Table 3). The majority (62.5%) provided minimal information about the interviewers (e.g. title or position), and 14 authors (29.2%) did not provide any information about personal characteristics. The vast majority of papers (87.5%) did not discuss the relationship and extent of interaction between interviewers/facilitators and participants. Only two papers explicitly discussed reflexivity, positionality, or potential personal bias based on the position of the researcher(s).

Discussion

The present study sought to examine how the field of health education and health behavior has conducted and reported qualitative analysis over the past 15 years. We found great variation in the type and depth of analytic information reported. Although we were able to identify several broad analysis trajectories, the terminology used to describe the approaches varied widely, and the analytic techniques used were not described in great detail.

While the majority of articles reported whether data were double-coded, single-coded, or a combination thereof, additional detail on the coding method was infrequently provided. Saldaña (2016) describes two primary sets of coding methods that can be used in various combination: foundational first cycle codes (e.g. In Vivo, descriptive, open, structural), and conceptual second cycle codes (e.g. focused, pattern, theoretical). Each coding method possesses a unique set of strengths and can be used either solo or in tandem, depending upon the analytic objectives. For example, In Vivo codes, drawn verbatim from participant language and placed in quotes, are particularly useful for identifying and prioritizing participant voices and perspectives (Saldana, 2016). Greater familiarity with, and more intentional application of, available techniques is likely to strengthen future research and accurately capture the ‘emic’ perspective of study participants.

Similarly, less than one quarter of studies described the use of matrices to organize coded data and support the identification of patterns, themes, and relationships. Matrices and other visual displays are widely discussed in the qualitative literature as an important organizing tool and stage in the analytic process (Miles et al., 2014; Saldana & Omasta, 2018). They support the analyst in processing large quantities of data and drawing credible conclusions, tasks which are challenging for the brain to complete when the text is in extended form (i.e. coded transcripts) (Miles et al., 2014). Like coding methods, myriad techniques exist for formulating matrices, which can be used for meeting various analytic objectives such as exploring specific variables, describing variability in findings, examining change across time, and explaining causal pathways (Miles et al., 2014). Most qualitative software packages have extended capabilities in the construction of matrices and other visual displays.

Most authors reflected on their findings as a whole in article discussion sections. However, explicit descriptions of how themes or concepts were grouped together or related to one another—made into something greater than the sum of their parts—were rare. Miles et al. (2014) describe two tactics for systematically understanding the data as a whole: building a logical chain of evidence that describes how themes are causally linked to one another, and making conceptual coherence by aligning these themes with more generalized constructs that can be placed in a broader theoretical framework. Only one study in our review described the development of theory; while not a required outcome of analysis, moving from the identification of themes and patterns to such “higher-level abstraction” is what enables a study to transcend the particulars of the research project and draw more widely applicable conclusions (Hennink et al., 2011; Saldana & Omasta, 2018).

All data analysis techniques will ideally flow from the broader inquiry framework and underlying paradigm within which the study is based (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2017; Creswell & Poth, 2018; Patton, 2015). Yet, as reported in our companion paper (Kegler et al. 2018), only six articles described the use of a well-established framework to guide their study (e.g. ethnography, grounded theory), making it difficult to assess how the reported analytic techniques aligned with the study’s broader assumptions and objectives. Interestingly, the most common analytic references were Miles & Huberman, Patton, and Bernard & Ryan, references which do not clearly align with a particular analytic approach or inquiry framework, and Strauss & Corbin, references aligned with grounded theory, an approach only reported in one of the included articles. In their Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, O’Brien et al. (2014) assert that chosen methods should not only be described, but also justified. Encouraging intentional selection of an inquiry framework and complementary analytic techniques can strengthen qualitative research by compelling researchers to think through the implicit assumptions, limitations, and implications of their chosen approach.

When discussing validity of the research, papers overwhelmingly focused on the limited generalizability of their findings (a dimension of quantitative validity that Maxwell (1996) maintains is largely irrelevant for qualitative methods, yet one that is likely requested by peer reviewers and editors), and few discussed methods specific to qualitative research (e.g., member checks, reading for negative cases). It is notable that one of the least used strategies was the exploration of negative or disconfirming cases, rival explanations, and divergent patterns, given the importance of this approach in several foundational texts (Miles et al., 2014; Patton, 2015). The primary focus on generalizability and the limited use of strategies designed to establish qualitative validity, may share a common root: the persistent hegemonic status of the quantitative paradigm. A more genuine embrace of qualitative methods in their own right may create space for a more comprehensive consideration of the specific nature of qualitative validity, and encourage investigators to apply and report such strategies in their work.

The researcher plays a unique role in qualitative inquiry: as the primary research instrument, they must subject their assumptions, decisions, actions, and conclusions to the same critical assessment they would any other instrument (Hennink et al., 2011). However, we found that reflexivity and positionality on the part of the researcher was minimally addressed in the scope of the papers we reviewed. We encourage our fellow researchers to be more explicit in discussing how their training, position, sociodemographic characteristics, and relationship with participants may shape their own theoretical and methodological approach to the research, as well as their analysis and interpretation of findings. In some cases, this reflexivity may highlight the critical importance of building in efforts to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of their research, including peer debriefs, audit trails, and member checks.

Limitations

The present study is subject to several important limitations. Clear consensus on qualitative reporting standards still does not exist, and it is not our intention to criticize the work of fellow researchers. Many of the articles included in our review were published prior to the release of Tong et al.’s (2007) Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research, O’Brien et al.’s (2014) Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research, and Levitt et al.’s (2018) Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research. Further, we could only assess articles based on the information reported. The information included in the articles may be incomplete due to journal space limitations and may not reflect all analytic approaches and techniques used in the study. Finally, our review was restricted to articles published in HE&B and is not intended to represent the conduct and reporting of qualitative methods across the entire field of health education and health behavior, or public health more broadly. As an official journal of the Society for Public Health Education, we felt that HE&B would provide a high quality snapshot of the qualitative work being done in our field. Future reviews should include qualitative research published in other journals in the field.

Implications

Qualitative research is one of the most important tools we have for understanding the complexity of human behavior, including its context-specificity, multi-level determinants, cross-cultural meaning, and variation over time. Although no clear consensus exists on how to conduct and report qualitative analysis, thoughtful application and transparent reporting of key “analytic building blocks” may have at least four interconnected benefits: 1) spurring the use of a broader array of available methods; 2) improving the ability of readers and reviewers to critically appraise findings and contextualize them within the broader literature; 3) improving opportunities for replication; and 4) enhancing the rigor of qualitative research paradigms.

This effort may be aided by expanding the use of matrices and other visual displays, diverse methods for coding, and techniques for establishing qualitative validity, as well as greater attention to researcher positionality and reflexivity, the broader conceptual and theoretical frameworks that may emerge from analysis, and a decreased focus on generalizability as a limitation. Given the continued centrality of positivist research paradigms in the field of public health, supporting the use and reporting of uniquely qualitative methods and concepts must be the joint effort of researchers, practitioners, reviewers, and editors—an effort that is embedded within a broader endeavor to increase appreciation for the unique benefits of qualitative research.

Figure 1.

Common analytic trajectories of qualitative papers in Health Education & Behavior, 2000–2015

Contributor Information

Ilana G. Raskind, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University 1518 Clifton Rd. NE, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA. ilana.raskind@emory.edu.

Rachel C. Shelton, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Dawn L. Comeau, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Hannah L. F. Cooper, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Derek M. Griffith, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA.

Michelle C. Kegler, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Bibliography and References Cited

- Bernard HR (1994). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR (2002). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR (2005). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (4th ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR, & Ryan GW (2010). Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge J, Clark MT, Herber OR, Wagstaff C, & Taylor J (2017). The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 627–645. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JM, & Strauss A (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Poth CN (2018). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Guba E (1978) Toward a methodology of naturalistic inquiry in educational evaluation CSE Monograph Series in Evaluation. Los Angeles: University of California, UCLA Graduate School of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink M, Hutter I, & Bailey A (2011). Qualitative Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Raskind IG, Comeau DL, Griffith DM, Cooper HLF, & Shelton RC (2018). Study Design and Use of Inquiry Frameworks in Qualitative Research Published in Health Education & Behavior. Health Education and Behavior, 0(0), 1090198118795018. doi: 10.1177/1090198118795018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R (1994). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R (1998) Analyzing & Reporting Focus Group Results Focus Group Kit 6 Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R, & Casey MA (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, Frost DM, Josselson R, & Suarez-Orozco C (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba E (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J (1996). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1984). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldana J (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, & Cook DA (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med, 89(9), 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (1987). How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, & Bernard HR (2000). Data management and analysis methods In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, & Bernard HR (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J, & Omasta M (2018). Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L, Ritchie J, Ormston R, O’Connor W, & Barnard M (2014). Analysis: Principles and Processes In Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nichols CM, & Ormston R (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students & Researchers (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin JM (1994). Grounded theory methodology In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin JM (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]