Abstract

Objectives:

Characterize patient expectations for integrating mental health into IBD treatment, describe experiences with psychotherapy, and evaluate therapy access and quality.

Methods:

Adults with IBD were recruited online and via a gastroenterology practice. Participants completed online questionnaires.

Results:

162 adults with IBD. The sample was primarily middle-aged, White, and female. Sixty percent had Crohn’s Disease. Disease severity was mild to moderate; 38% reported utilizing therapy for IBD-specific issues. The greatest endorsed barrier to psychotherapy was cost. Psychotherapy was perceived as leading to modest gains in quality of life, emotional well-being, and stress reduction. Participants reported a disparity between their desire for mental health discussions and their actual interactions with providers. The majority of participants (81%) stated there are insufficient knowledgeable therapists.

Conclusions:

A significant number of patients with IBD endorsed the desire for mental health integration into care. Disparities exist in reported provider-patient communication on these topics. There appears to be a dearth of IBD-knowledgeable therapists in the community.

Keywords: Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn’s Disease, Mental Health, Psychotherapy, Psychosocial Care, Integrated Care, Community

Introduction:

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are complex chronic diseases characterized by symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, rectal bleeding, and extraintestinal symptoms (Ko & Auyeung, 2014). Treatment for IBDs typically focus on disease symptoms and flare prevention, addressed through medications and/or surgery (Colombel, Narula, & Peyrin-Biroulet, 2017; Mowat et al., 2011). While treat-to-target interventions are increasingly efficacious in symptom and inflammation mitigation, many patients experience side effects and eventual relapse, creating the potential for substantial illness burden and decreased health-related quality of life (Devlen et al., 2014; Kaplan, 2015; Keeton, Mikocka-Walus, & Andrews, 2015; Lonnfors et al., 2014).

Adults with IBD appear to be at an increased risk for psychological disorders, particularly anxiety and depressive disorders, when compared to both healthy and chronic illness populations (Hauser, Janke, Klump, & Hinz, 2011; Walker et al., 2008). Research into the presence of psychological distress and its relationship with patient reported outcomes repeatedly demonstrates that psychological comorbidities may negatively impact the IBD course, patient quality of life, and can make disease management and medication adherence more challenging (Graff, Walker, & Bernstein, 2009; Lix et al., 2008; A. A. Mikocka-Walus et al., 2007; Neuendorf, Harding, Stello, Hanes, & Wahbeh, 2016; Sainsbury & Heatley, 2005). Despite these significant negative impacts, it appears that psychological comorbidities are undertreated among IBD patients (Bennebroek Evertsz et al., 2012). An important step to addressing this disparity was the release of a White Paper from the American Gastroenterological Association advocating for increased integration of psychosocial management in IBD care (Szigethy et al., 2017). While the paper provided evidence-based recommendations from health centers for this integration, it did not include patients’ perspectives on the importance of mental health integration in IBD care, their experiences, or their preferred approaches for care.

There are multiple ways IBD providers can integrate mental health into patient care; this decision may be influenced by the provider’s knowledge of mental health, their awareness of patients’ psychosocial state or desire for referral, and availability of resources (Szigethy et al., 2017). When integrated successfully, patients are referred to mental health providers but the efficacy of treatment may vary and it remains unexplored if therapist knowledge of IBD is important (Knowles, Monshat, & Castle, 2013; Szigethy et al., 2017).

Reviews of studies investigating psychotherapy among IBD patients observe a range of approaches and find the efficacy of treatments to be mixed (Ballou & Keefer, 2017; Fiest et al., 2016; Knowles et al., 2013; Mehta et al., 2015; von Wietersheim & Kessler, 2006). Psychotherapy approaches include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Hypnotherapy, Psychodynamic and Interpersonal Therapies, and Mindfulness-Based Therapies, with CBT approaches showing the most consistent efficacy (Ballou & Keefer, 2017; Keefer & Keshavarzian, 2007; Keefer et al., 2011; Knowles et al., 2013; A. Mikocka-Walus, Knowles, Keefer, & Graff, 2016). A recent randomized controlled trial among 174 IBD patients compared the efficacy of CBT (face-to-face or online) to standard treatment in managing disease course and mental health (A. Mikocka-Walus et al., 2015). While CBT did not impact disease activity, it significantly improved quality of life among a subgroup of ‘in need’ patients with poorer mental health, demonstrating that CBT may be more effective in the context of clinical or demographic factors (A. Mikocka-Walus et al., 2015). Additionally, the efficacy of face-to-face CBT versus online CBT was not significantly different, providing support for a therapeutic approach that decreases a barrier to care (A. Mikocka-Walus et al., 2015). This study is supported by another online intervention that used a CBT workbook with minimal therapist feedback among IBD patients (Hunt, Rodriguez, & Marcelle, 2017). Participants that completed the six online modules experienced significant improvements in visceral anxiety, GI specific catastrophizing, and levels of depression compared to the waitlist controls (Hunt et al., 2017). Similar to the previous intervention, Hunt, Rodriquez & Marcelle (2017) identified that a sub-group of participants benefited (those who completed treatment), again suggesting the importance of demographic or clinical factors. Both of these studies used accessible platforms that could potentially be easily integrated into standard IBD care, however both suffered from high attrition rates indicating a need to better understand patient’s experiences, needs, and preferences for mental health treatment.

While investigations of prevalence of psychological distress and appropriate psychotherapy treatment expands in IBD, limitations exist. In addition to mixed results, most psychotherapy treatment studies are restricted to controlled settings, have a limited number of participants, and do not investigate IBD patient perspectives. Two very recent studies published in German and Spanish populations indicate a demand for psychotherapy in IBD (Klag et al., 2017; Marin-Jimenez et al., 2017). However, no study to date has evaluated IBD patient experiences and preferences for a multidisciplinary approach to care in the U.S.. This study aims to:

Aim 1: Characterize patient expectations for integrating mental health into IBD care and the role of the IBD physician in this integration.

Aim 2: Characterize the psychological treatments that IBD patients use as part of their illness management.

Aim 3: Evaluate treatment satisfaction in patients regarding referrals they receive and the psychotherapy care received.

Aim 4: Identify barriers to accessing psychotherapy.

Methods:

Potential participants were recruited online via social media (Facebook, Twitter) and a research dedicated website (researchmatch.org). An email solicitation was sent to existing IBD patients seen in an outpatient, university-based gastroenterology practice. The online advertisements and email solicitation used similar language, sharing that “We are doing a research study to learn more about how individuals living with IBD find out about therapy services, their interest in receiving this information from their physicians, and their experiences with therapy services”. After completing a modified informed consent for online surveys, participants were directed to screening questions and a series of questionnaires hosted online by the third party survey system, RedCap. Participants were included if they had a diagnosis of IBD and were between 18 to 70 years old. Participants were excluded if were unable to consent, not yet an adult, or were a prisoner.

Demographic information:

Age, gender, marital status, education level, annual household income, population of community of residence including urban versus non-urban classification, and recruitment source (online or clinic). As cultural differences exist in how individuals perceive psychotherapy (Meyer & Zane, 2013), race and ethnicity were collected through a categorical question.

Clinical information:

IBD diagnosis (Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, Indeterminate Colitis), age at symptom onset, age at diagnosis, primary IBD treatment provider type (e.g. gastroenterologist that is an IBD specialist, general gastroenterologist), current medications (prescribed and over-the-counter), number of outpatient visits for IBD in past year, quality of relationship with IBD treatment provider (5-point Likert Scale: Excellent to Poor), quality of communication with IBD treatment provider (5-point Likert Scale: Excellent to Poor).

Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) (Bennebroek Evertsz et al., 2013):

The patient HBI is a 5-item scale widely used to gauge symptom severity in IBD patients. Items consist of ratings of abdominal pain, extraintestinal symptoms, liquid stools, abdominal mass, and general well-being. Total scores were calculated and are reported as mean ± standard deviation. Maximum score is 26. Scores < 8 indicate mild disease, 8 to 16 moderate disease, and > 16 severe disease.

Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ)(Irvine, Zhou, & Thompson, 1996):

The SIBDQ is a 10-item measure of health related quality of life derived from the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ). Items are measured on a 7-point Likert scale with a maximum score of 70. Higher scores denote greater quality of life. The SIBDQ is reliable and valid across multiple IBD studies.

IBD Patient Psychotherapy Experiences:

A study specific questionnaire was used to gauge the mental health treatment needs of IBD patients, with several domains assessed. Five questions evaluated whether IBD treating providers discussed mental health aspects of IBD and whether they had provided a referral to a mental health provider; for participants who checked “No”, a follow-up question was shown asking if they would like their provider to discuss the topic (e.g. “Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever discussed the impact of stress on IBD?” “Do you wish your treatment provider would discuss the role of stress in IBD?” (Presented only to “no” responses)). Next, participants were asked if they were currently seeing a therapist or had seen one in the past to address stress or emotional well-being related to IBD. For those who endorsed “Yes”, a series of questions about their experience with therapy, including four items assessing their impression of therapy’s effectiveness using visual analog scales, were shown. All participants were then asked questions related to barriers to accessing mental health care. See Appendix A for the complete survey.

Statistical Analyses

Data were exported from the online survey system directly into SPSS v. 24 for analyses. Participants with ≥ 25% missing data were identified and removed from the sample. Due to the small number of participants in each non-Caucasian racial group, these were combined to dichotomize race by Caucasian and non-Caucasian; diagnosis was also dichotomized to CD or UC/IC due to the small number of IC participants. Preliminary descriptive statistics (percentage, mean ± standard deviation) analyzed the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample, symptom severity, and HRQOL. A series of Chi-Square analyses determined significant differences across categorical demographic and clinical variables for psychotherapy utilization (Current, Past, Never). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc test evaluated differences for each continuous variable (age, SIBDQ, HBI) for psychotherapy utilization. Percentages and mean ± standard deviation summarized the items related to patient experiences with psychotherapy and provider discussions related to mental health. Independent samples t-tests determined differences between CD and UC/IC for ratings of therapist knowledge and effectiveness of psychotherapy.

Ethical Considerations:

The study was conducted with the approval of the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00203936). Each participant provided informed consent and only de-identified data are presented.

Results:

One hundred and seventy-nine patients consented to the study. Those with ≥ 25% missing data were removed from analysis (N = 17), leaving a total study sample of 162. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. [Table 1 and 2 near here].

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample

| N = 162 | |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 38.85 ± 13.63 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16.9% (31) |

| Female | 70.5% (129) |

| Transgender | 1.1% (2) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 79.2% (145) |

| African American/Black | 3.8% (7) |

| Latino(a) | 1.1% (2) |

| Asian American | 0.5% (1) |

| Multiracial | 2.2% (4) |

| Other | 1.1% (2) |

| Non-Hispanic Ethnicity | 85.8% (157) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 30.6% (56) |

| Married/Life Partner | 50.3% (92) |

| Divorced/Separated | 7.1% (13) |

| Employed | |

| Part or Full Time | 58.6% (95) |

| Unemployed or Disability | 25.3% (41) |

| Student | 12.3% (20) |

| Homemaker | 3.7% (6) |

| Annual Household Income > $50,000 | 54.9% (89) |

| College Educated | 64.2% (104) |

| Urban Dweller | 75.8% (122) |

| Community Population | |

| < 10,000 | 14.8% (24) |

| 10,000 – 99,999 | 38.9% (63) |

| 100,000 – 1,000,000 | 26.5% (43) |

| > 1,000,000 | 19.8% (32) |

| Recruitment Source | |

| Outpatient Clinic | 3.3% (5) |

| Social Media | 42.5% (65) |

| Researchmatch.org | 50.3% (77) |

| Other | 3.2% (6) |

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Sample

| N = 162 | |

|---|---|

| IBD Diagnosis | |

| Crohn’s Disease | 58.8% (96) |

| Ulcerative Colitis (includes post-colectomy) | 39.0% (63) |

| Indeterminate Colitis | 1.7% (3) |

| Primary IBD Treatment Provider | |

| Internist/Primary Care Physician | 9.3% (15) |

| General Gastroenterologist | 37.9% (61) |

| IBD Specialist | 48.4% (79) |

| Nurse Practitioner/Advanced Practice Nurse | 2.5% (4) |

| Other | 1.9% (3) |

| Current Medication | |

| Antibiotics | 2.2% (4) |

| Aminosalicylates | 23.5% (43) |

| Steroids | 13.1% (24) |

| Immunomodulators | 19.1% (35) |

| Biologic Therapies | 43.2% (79) |

| Other Prescribed Medications | 15.8% (29) |

| Over the Counter Medication, Supplements, Probiotics | 57.1% (92) |

| Age Symptom Onset (years) | 24.60 ± 44.22 |

| Age of Diagnosis (years) | 26.58 ± 12.40 |

| Harvey Bradshaw Index Score | 8.89 ± 4.66 |

| SIBQ Score | 43.23 ± 12.58 |

| Number of Outpatient Visits for IBD (past year) | 4.52 ± 8.68 |

| Good or Excellent Relationship with IBD Provider | 80.6% (129) |

| Good or Excellent Communication with IBD Provider | 74.5% (120) |

Participants tended to be female, Caucasian, non-Hispanic, college-educated, living in an urban community with a mean age of 39 years (± 14). Sixty percent indicated having CD, 48% reported seeing an IBD specialist, and the mean HBI score indicated mild to moderate disease (Range: 4 to 26), while HRQOL ranged from poor to high (SIBDQ Range: 10 to 68). Greater than three quarters endorsed a positive physician-patient relationship with good communication.

Evaluation of Psychotherapy Utilization by Demographic and Clinical Variables

No significant differences existed by IBD diagnosis for psychotherapy utilization, so the entire sample was pooled for the following analyses. Chi-square for reported psychotherapy use by categorical demographic and clinical variables indicated significant differences only for annual household income, with patients earning $30,000 or less per year more likely to have sought psychotherapy than those of higher income brackets (χ2 = 21.36, p = .045), and for primary IBD treatment provider, with those reporting seeing an IBD specialist more likely to endorse being in therapy than those treated by other providers (χ2 = 18.16, p = 0.02). Analysis of variance for continuous demographic and clinical variables identified patients reporting younger age of diagnosis as being more likely to use psychotherapy (F = 3.28, p = .04) and patients who did not endorse using psychotherapy reporting higher HRQOL (F = 3.20, p = .043). No other significant differences existed between groups for psychotherapy utilization. However, marital status (p = .068) and education level (p = .075) approached significance.

Congruence Between Provider Discussion of Mental Health Topics and Patient Needs

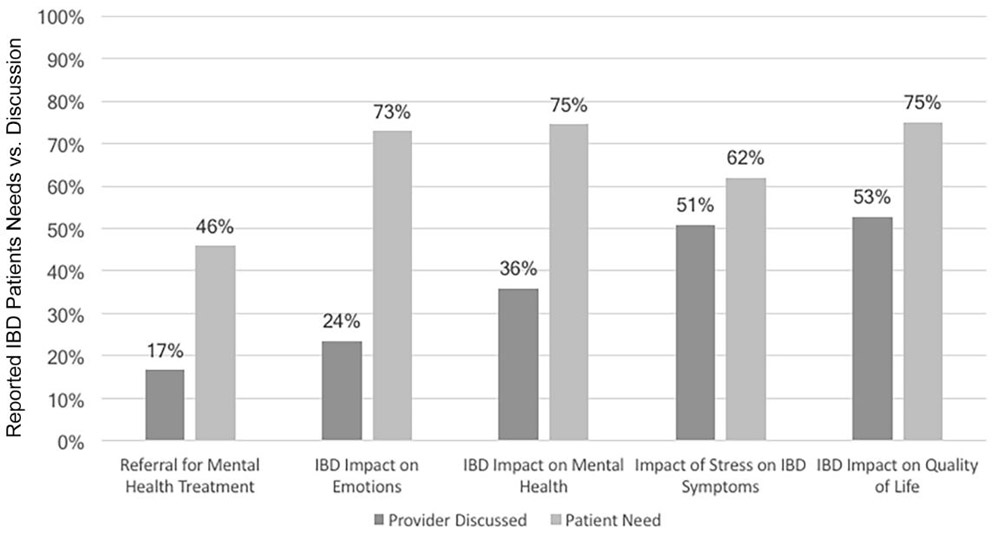

Most participants agreed or strongly agreed that stress had an impact on IBD symptoms (70%), negatively impacted HRQOL (61%), and impaired emotional well-being (54%). Less endorsed IBD as having a negative impact on social interactions (45%) and experiencing IBD related stigma (17%). Ninety-five percent of participants agreed that stress, quality of life, and mental health should be addressed by their medical providers. However, disparities exist between recalled provider discussions about mental health topics and patient desires to have such conversations (Figure 1). Participants recalled that providers were least likely to discuss the topic of referral for mental health treatment, followed by the impact IBD has on emotional well-being, and how IBD may cause anxiety or depression. Providers were remembered as more likely to discuss HRQOL and the role of stress in IBD symptoms. Of patients who indicated their physician had not discussed these topics, most endorsed wanting these conversations to occur..

Figure 1.

Reported IBD patients’ needs vs. provider discussion regarding mental health considerations

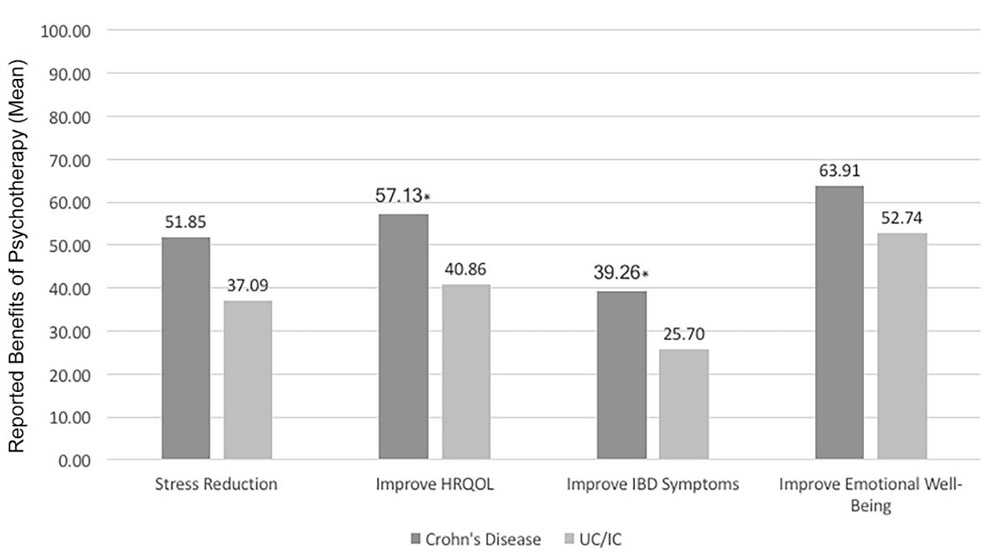

Patient Experiences with Community-Based Psychotherapy

Thirty-eight percent of participants reported either current or prior psychotherapy to address IBD-specific issues (Table 3). Non-IBD treatment providers (e.g. Primary Care Physician not involved in IBD treatment) were more likely to provide the referral for mental health services and participants shared they were referred to both master’s and doctoral level therapists equally. Of patients referred to a psychiatrist (7%), 60% remembered receiving a prescription for a psychotropic medication. Most participants (56%) indicated they recalled engaging in cognitive-behavioral therapy (includes mindfulness and stress management) followed by supportive therapy (25%). The remaining approaches, such as psychodynamic, existential/humanistic, biofeedback, and hypnotherapy each received less than 5% endorsement. Participants felt that psychotherapy was most effective in improving emotional well-being and HRQOL (Figure 2), followed by stress management and symptom reduction. Two differences existed by diagnosis, with CD patients reporting significantly more improvement in HRQOL and IBD symptoms than UC/IC patients.

Table 3.

. Patient Experiences with Mental Health Treatment

| Percent(N) | |

|---|---|

| Therapy Utilization | |

| Current | 15.4% (24) |

| Past | 23.1% (36) |

| None | 61.5% (96) |

| Ability to Find Therapist | |

| No Issues | 15.0% (23) |

| Saw 1-2 therapists | 10.5% (16) |

| Saw > 2 therapists | 4.6% (7) |

| Gave Up | 9.8% (15) |

| Found Therapist By | |

| Referral from Non-IBD Treating Provider | 34.5% (20) |

| Referral from IBD Treating Provider | 19.0% (11) |

| Internet Search | 17.2% (10) |

| Word of Mouth | 10.3% (6) |

| Patient Organization | 3.4% (2) |

| Other | 15.5% (9) |

| Therapy Payment | |

| Self-Pay/Out of Pocket | 19.0% (11) |

| Insurance with Co-Payment | 50.0% (29) |

| Insurance without Co-Payment | 19.0% (11) |

| Part of Medical Program | 5.2% (3) |

| Other | 6.9% (4) |

| Prescribed Medication (Only if referred to psychiatrist) | 59.3% (16) |

Figure 2.

Ratings of psychotherapy effectiveness by diagnosis

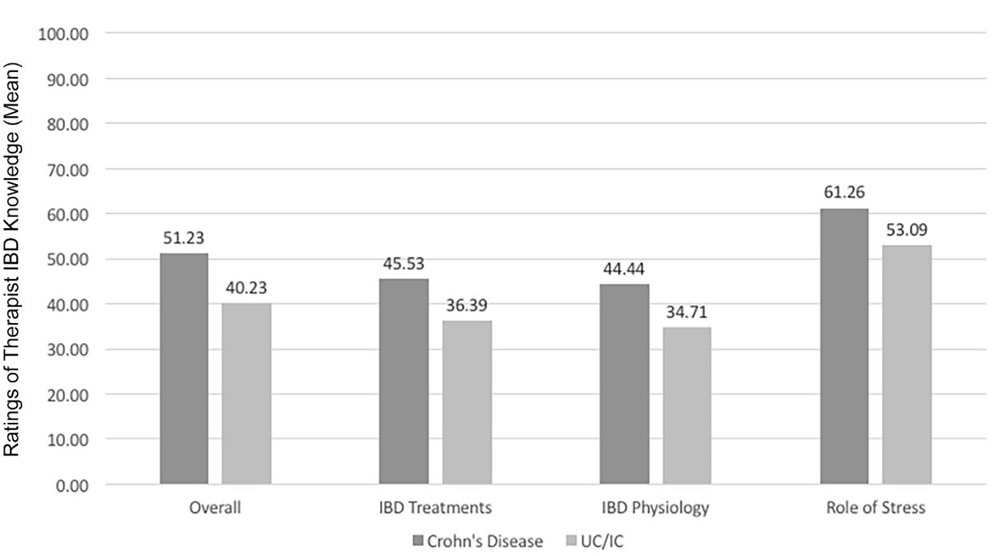

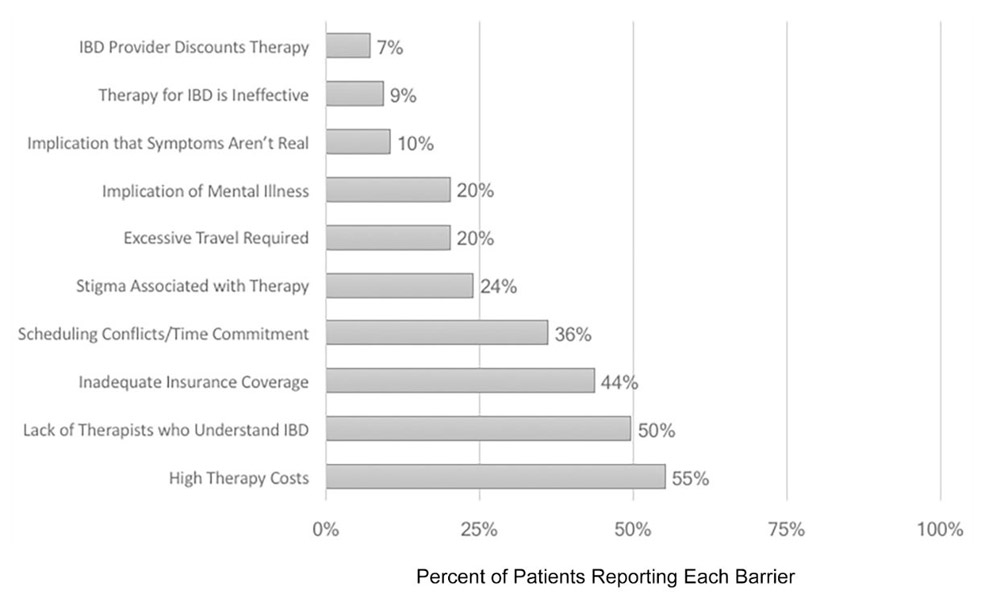

Barriers to Psychotherapy for IBD

The majority (81%) of participants stated there are not enough knowledgeable therapists to meet the mental health needs of people living with IBD. Only 11% felt a therapist being knowledgeable about IBD was slightly or not at all important. In general, both CD and UC/IC patients did not rate therapists as highly knowledge of IBD (Figure 3). Participants viewed that therapists’ knowledge was strongest for the emotional impact of IBD, while understanding of IBD physiology and treatment was relatively low..

Figure 3.

Ratings of therapist knowledge of IBD domains by diagnosis

Participants reported that the greatest barrier to psychotherapy was cost (55%; Figure 4) even though 69% used health insurance to cover fees for services; 44% did cite inadequate insurance coverage as a barrier. Stigma about therapy and the implication of mental illness was a concern for approximately 20% of respondents. Logistical issues (travel, time commitment, scheduling conflicts) were barriers for approximately one third of patients. Negative opinions about the effectiveness of psychotherapy, either from themselves or their treatment providers, were uncommon (< 10%).

Figure 4.

Reported barriers to accessing psychotherapy for IBD

Discussion:

This retrospective cross-sectional survey of IBD patients in the community provides important and novel views about IBD patient experiences with psychotherapy and their perspectives on the integration of mental health issues into IBD management. Congruent with the psychosocial IBD literature, many participants in the present study endorsed that stress negatively impacts their IBD symptoms, HRQOL, and emotional wellbeing. Ninety-five percent of participants agreed these issues should be addressed by their medical providers. Despite this desire, patients reported recalling that many providers were not meeting their need to discuss mental health and IBD, including referral for treatment.

Thirty-eight percent of participants reported using psychotherapy to address IBD-specific issues. According to a 2007 report, psychotherapy utilization in the general US population has remained relatively stable in the last three decades, with most recent estimates at 3.2% (Olfson & Marcus, 2010), suggesting that considerably more IBD patients seek mental health services than average. Additionally, rates of reported psychotherapy use in our sample paralleled those of patients in the 2007 report with depressive disorders (43%) and anxiety disorders (35%) and align with current estimates of depression and anxiety in this patient population.

Our study also found that certain groups were more likely to endorse taking advantage of psychotherapy, including IBD patients earning $30,000 or less per year. This outcome is intriguing in light of the result that cost of psychotherapy was reported as its greatest barrier. This suggests that patients with lower incomes may be under disproportionate stress, perhaps in part due to rising healthcare costs in the US healthcare system including higher co-payments, deductibles, and annual maximum out-of-pocket expenses (Patel et al., 2017). Fortunately, psychotherapy research in gastrointestinal disorders is demonstrating that online therapies can increase access to evidence-based treatments while maintaining efficacy (Hunt et al., 2017; Ljótsson et al., 2011). The other groups more likely to endorse seeking therapy were patients using an IBD specialist as their primary IBD treatment provider and patients diagnosed at a younger age. While participants reported remembering that referrals tended to come from non-IBD treatment providers (e.g. Internist), those being seen by an IBD specialist likely have had a more severe disease course, as is also true of those diagnosed at a younger age which, in turn, may lead to increased psychological distress.

Similar to the findings of two recent reviews (Knowles et al., 2013; McCombie, Mulder, & Gearry, 2013), the perceived effectiveness of psychotherapy among this study’s participants was mixed. Those who reported using psychotherapy to address IBD-specific issues were asked to share their impressions on its efficacy via visual analog scales. Patients typically recalled modest improvements in emotional well-being, HRQOL, stress management and symptom reduction. CD patients reported somewhat better outcomes than UC/IC but these data are self-reported, are not from a standardized measure, and thus should be interpreted with caution. Most participants remembered using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as their primary treatment modality in therapy, which is encouraging as CBT is one of the more researched, evidence-based psychotherapy approaches for IBD (Gracie, 2017; A. Mikocka-Walus et al., 2015).

Our findings indicate a desire and need among IBD patients for psychotherapy, as found in non-US populations (Klag et al., 2017; Marin-Jimenez et al., 2017; Miehsler et al., 2008). Yet, despite reported high levels of satisfaction in both the patient-physician relationship and in quality of communication, gaps exist between patient desires and reported physician actions. This disparity in patient needs and provider recommendations was also recently observed in a Spanish cohort (Marin-Jimenez et al., 2017). Prior research suggests that patients are often vague when communicating their desires for referrals (Peck et al., 2004; Rao, Weinberger, & Kroenke, 2000) and it is unknown if participants in this study actually voiced their desires for mental health integration to their providers. As mental health is a stigmatized subject (Clement et al., 2015; Dockery et al., 2015; Taft & Keefer, 2016), both patients and providers may skirt this issue as the proverbial “elephant in the room” and focus time during the appointment on other topics. This, in addition to the barriers of cost, the lack of knowledge by providers and patients regarding the benefits of psychotherapy, the perception that there is a dearth of therapists who understand IBD, and logistical issues may help explain why some participants who want psychotherapy have not engaged.

While the findings from this study support and advance work in the area of IBD and psychosocial health, limitations exist. This study relied primarily on internet-based recruitment methods. While internet samples are gaining popularity and credibility (Kosinski, Matz, Gosling, Popov, & Stillwell, 2015; Lammert, Comerford, Love, & Bailey, 2015), online studies universally come with considerations when interpreting their findings including that all data collected involves self-report, thus constraining what can be inferred from the results (Kapp, Peters, & Oliver, 2013; Khatri et al., 2015). As we relied on self-report measures for IBD diagnosis, we cannot confirm all participants have IBD. However, it is unlikely that a significant percentage of participants falsified their illness status. The majority of participants were female and Caucasian – two groups commonly known to be more open to psychotherapy (Olfson & Marcus, 2010). Also, topics participants may not know the answer to (therapeutic approach) or may not remember (conversations with IBD providers) were solicited. On the other hand, we failed to solicit the reasons why participants did not attend psychotherapy, limiting our understanding of barriers to care. Further, the online sample may be biased in other characteristics, such as greater psychological distress (Jones, Bratten, & Keefer, 2007) or a high desire for IBD mental health care. Future studies that use qualitative methods and that include more diverse samples are warranted as they will provide richer, more comprehensive information and will mitigate some of these biases.

Conclusion:

Our findings suggest IBD patients want psychosocial issues to be addressed, both in conversations with their GI provider and through mental health referrals, yet gaps exist in care. As treatment for IBD patients continues to evolve, the integration of psychosocial approaches into standard IBD treatment paradigms should be a priority. The integration is not only desired by patients, but could strengthen efficacy and implementation research on which psychotherapy approaches are the most effective and with whom, in real-world settings. Expanding research on the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of a multidisciplinary approach to IBD management and increasing opportunities for mental health providers to gain expertise in gastroenterology are also necessary, especially in light of patient perceptions that there are insufficient mental health providers who are knowledgeable about IBD and given the marginal improvements across patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments:

This work was partially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases under training grant T32DK101363.

Appendix A. Study-Specific Survey of Patient Experiences with Psychotherapy

| Question | Scoring System |

|---|---|

| Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever discussed with you the impact of stress on IBD? | Yes/No |

| Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever discussed with you the impact IBD has had on your quality of life? | Yes/No |

| Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever discussed with you the impact IBD has had on your mental health (anxiety, depression, etc.)? | Yes/No |

| Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever discussed with you the impact IBD has on your emotions? | Yes/No |

| Has your primary IBD treatment provider ever provided you with a referral to see a mental health provider such as a therapist or counselor? | Yes/No |

| Which type of provider were you referred to? | Multiple selection |

| If you were referred to a psychiatrist, did you receive medication to treat your mood, anxiety, or other emotional symptoms? | Yes/No |

| Are you currently seeing a therapist, or have you seen one in the past, to address stress or your emotional well-being as it relates to your IBD? | Multiple Choice |

| Did you have trouble finding a therapist that you felt understood your issues related to IBD or who you clicked with? | Multiple Choice |

| How did you find your therapist? | Multiple Choice |

| To date, how many times have you seen your therapist? | Multiple Choice |

| How did/do you pay for your therapy sessions? | Multiple Choice |

| What approaches to treatment did/does your therapist use with you in your sessions? Often times a therapist will use more than one method so check all that apply. | Multiple Selection |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being no knowledge, 10 being excellent knowledge) please rate your therapists overall understanding of IBD | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being no knowledge, 10 being excellent knowledge) please rate your therapists understanding of IBD treatments | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being no knowledge, 10 being excellent knowledge) please rate your therapists understanding of the physiology of IBD (e.g autoimmune, inflammatory, difference between Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis) | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being no knowledge, 10 being excellent knowledge) please rate your therapists understanding of the role of stress in IBD | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being no knowledge, 10 being excellent knowledge) please rate your therapists understanding how IBD impacts emotional well being | VAS |

| How important is it to you that your therapist be knowledgeable about IBD? | Likert Scale |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being not at all, 10 being extremely) how effective has therapy been in addressing how stress impacts your IBD? | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being not at all, 10 being extremely) how effective has therapy been in improving your quality of life with IBD? | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being not at all, 10 being extremely) how effective has therapy been in improving your IBD symptoms? | VAS |

| On a scale of 0 to 10 (0 being not at all, 10 being extremely) how effective has therapy been in improving your emotional well-being? | VAS |

| In your opinion, do you feel stress, quality of life, and your mental health should be addressed or discussed by your medical providers? | Yes/No |

| Which of the following issues that people living with IBD commonly face do you think therapy can help with (check all that apply)? | Multiple selection |

| Do you feel there are enough knowledgeable therapists available to meet the mental health needs of people living with IBD? | Yes/No |

| What are some of the barriers to seeking therapy for IBD related issues that you or other people living with IBD experience (check all that apply)? | Multiple selection |

VAS: Visual Analog Scale

Footnotes

Disclosures:

MC: Nothing to disclose

SQ: Nothing to disclose

TT: Nothing to disclose

References:

- Ballou S, & Keefer L (2017). Psychological Interventions for Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 8(1), e214. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennebroek Evertsz F, Hoeks CC, Nieuwkerk PT, Stokkers PC, Ponsioen CY, Bockting CL, … Sprangers MA (2013). Development of the patient Harvey Bradshaw index and a comparison with a clinician-based Harvey Bradshaw index assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. J Clin Gastroenterol, 47(10), 850–856. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31828b2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennebroek Evertsz F, Thijssens NA, Stokkers PC, Grootenhuis MA, Bockting CL, Nieuwkerk PT, & Sprangers MA (2012). Do Inflammatory Bowel Disease patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms receive the care they need? J Crohns Colitis, 6(1), 68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, … Thornicroft, G (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med, 45(1), 11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombel JF, Narula N, & Peyrin-Biroulet L (2017). Management Strategies to Improve Outcomes of Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology, 152(2), 351–361 e355. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlen J, Beusterien K, Yen L, Ahmed A, Cheifetz AS, & Moss AC (2014). The burden of inflammatory bowel disease: a patient-reported qualitative analysis and development of a conceptual model. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 20(3), 545–552. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000440983.86659.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery L, Jeffery D, Schauman O, Williams P, Farrelly S, Bonnington O, … group M. s. (2015). Stigma- and non-stigma-related treatment barriers to mental healthcare reported by service users and caregivers. Psychiatry Res, 228(3), 612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiest KM, Bernstein CN, Walker JR, Graff LA, Hitchon CA, Peschken CA, … managing the effects of psychiatric comorbidity in chronic immunoinflammatory, d. (2016). Systematic review of interventions for depression and anxiety in persons with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Res Notes, 9(1), 404. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2204-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, Mikocka-Walus A, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC (2017). Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2(3), 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff LA, Walker JR, & Bernstein CN (2009). Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 15(7), 1105–1118. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser W, Janke KH, Klump B, & Hinz A (2011). Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 17(2), 621–632. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MG, Rodriguez L, & Marcelle E (2017). A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Workbook Delivered Online with Minimal Therapist Feedback Improves Quality of Life for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, & Thompson AK (1996). The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol, 91(8), 1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MP, Bratten J, & Keefer L (2007). Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome differs between subjects recruited from clinic or the internet. Am J Gastroenterol, 102(10), 2232–2237. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01444.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GG (2015). The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 12(12), 720–727. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp JM, Peters C, & Oliver DP (2013). Research recruitment using Facebook advertising: big potential, big challenges. J Cancer Educ, 28(1), 134–137. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0443-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefer L, & Keshavarzian A (2007). Feasibility and acceptability of gut-directed hypnosis on inflammatory bowel disease: a brief communication. Int J Clin Exp Hypn, 55(4), 457–466. doi: 10.1080/00207140701506565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Martinovich Z, Cohen E, Van Denburg A, & Barrett TA (2011). Behavioral interventions may prolong remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Behav Res Ther, 49(3), 145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton RL, Mikocka-Walus A, & Andrews JM (2015). Concerns and worries in people living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A mixed methods study. J Psychosom Res, 78(6), 573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri C, Chapman SJ, Glasbey J, Kelly M, Nepogodiev D, Bhangu A, … Committee ST (2015). Social media and internet driven study recruitment: evaluating a new model for promoting collaborator engagement and participation. PLoS One, 10(3), e0118899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klag T, Mazurak N, Fantasia L, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Kirschniak A, Falch C, … Wehkamp J (2017). High Demand for Psychotherapy in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles SR, Monshat K, & Castle DJ (2013). The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 19(12), 2704–2715. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318296ae5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JK, & Auyeung KK (2014). Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology, pathogenesis and current therapy. Curr Pharm Des, 20(7), 1082–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski M, Matz SC, Gosling SD, Popov V, & Stillwell D (2015). Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. Am Psychol, 70(6), 543–556. doi: 10.1037/a0039210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert C, Comerford M, Love J, & Bailey JR (2015). Investigation Gone Viral: Application of the Social Mediasphere in Research. Gastroenterology, 149(4), 839–843. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lix LM, Graff LA, Walker JR, Clara I, Rawsthorne P, Rogala L, … Bernstein CN (2008). Longitudinal study of quality of life and psychological functioning for active, fluctuating, and inactive disease patterns in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 14(11), 1575–1584. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Lindfors P, Hursti T, Lindefors N, Andersson G, & Rück C (2011). Long-term follow-up of internet-delivered exposure and mindfulness based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(1), 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, & Avedano L (2014). IBD and health-related quality of life -- discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis, 8(10), 1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Jimenez I, Gobbo Montoya M, Panadero A, Canas M, Modino Y, Romero de Santos C, … Barreiro-de Acosta M (2017). Management of the Psychological Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Perspective of Doctors and Patients-The ENMENTE Project. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 23(9), 1492–1498. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombie AM, Mulder RT, & Gearry RB (2013). Psychotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review and update. J Crohns Colitis, 7(12), 935–949. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona AC, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, … Thornicroft G (2015). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry, 207(5), 377–384. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.151944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer OL, & Zane N (2013). THE INFLUENCE OF RACE AND ETHNICITY IN CLIENTS’EXPERIENCES OF MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT. Journal of community psychology, 41(7), 884–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehsler W, Weichselberger M, Offerlbauer-Ernst A, Dejaco C, Reinisch W, Vogelsang H, … Moser G (2008). Which patients with IBD need psychological interventions? A controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 14(9), 1273–1280. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, Hughes P, Esterman A, & Andrews JM (2015). Cognitive-behavioural therapy has no effect on disease activity but improves quality of life in subgroups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol, 15, 54. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0278-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, & Graff L (2016). Addressing Psychological Needs of Individuals with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Necessary. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 22(6), E20–21. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, & Holtmann GJ (2007). Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 13(2), 225–234. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, … Bloom S (2011). Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut, 60(5), 571–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, & Wahbeh H (2016). Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res, 87, 70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, & Marcus SC (2010). National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry, 167(12), 1456–1463. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Jensen A, Ramirez E, Tariq M, Lang I, Kowalski-Dobson T, … Lichtenstein R (2017). Health Insurance Challenges in the Post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) Era: a Qualitative Study of the Perspective of Low-Income People of Color in Metropolitan Detroit. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0344-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck BM, Ubel PA, Roter DL, Goold SD, Asch DA, Jeffreys AS, … Tulsky JA (2004). Do unmet expectations for specific tests, referrals, and new medications reduce patients’ satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med, 19(11), 1080–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30436.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JK, Weinberger M, & Kroenke K (2000). Visit-specific expectations and patient-centered outcomes: a literature review. Arch Fam Med, 9(10), 1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury A, & Heatley RV (2005). Review article: psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 21(5), 499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szigethy EM, Allen JI, Reiss M, Cohen W, Perera LP, Brillstein L, … Colton JB (2017). White Paper AGA: the impact of mental and psychosocial factors on the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15(7), 986–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft TH, & Keefer L (2016). A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol, 9, 49–58. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S83533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wietersheim J, & Kessler H (2006). Psychotherapy with chronic inflammatory bowel disease patients: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 12(12), 1175–1184. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000236925.87502.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, Greenfeld JM, Clara I, Lix L, … Bernstein CN (2008). The Manitoba IBD cohort study: a population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am J Gastroenterol, 103(8), 1989–1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]