Significance

The electronic structure of the heme oxy-iron center in oxyhemoglobin and oxymyoglobin has been the subject of debate for decades. Various experimental and computational methods have been used to study this system, leading to conflicting conclusions. This study uses X-ray spectroscopy to directly probe the iron center in the highly delocalized oxyhemoglobin and its model compound to define the electronic structure and understand the differences between the protein and the model. This study settles a longstanding debate in bioinorganic chemistry and provides insight into heme iron–oxygen binding, the key first step in many biocatalytic processes.

Keywords: X-ray spectroscopy, resonant inelastic X-ray scattering, DFT, oxyhemoglobin, electronic structure

Abstract

Hemoglobin and myoglobin are oxygen-binding proteins with S = 0 heme {FeO2}8 active sites. The electronic structure of these sites has been the subject of much debate. This study utilizes Fe K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and 1s2p resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) to study oxyhemoglobin and a related heme {FeO2}8 model compound, [(pfp)Fe(1-MeIm)(O2)] (pfp = meso-tetra(α,α,α,α-o-pivalamido-phenyl)porphyrin, or TpivPP, 1-MeIm = 1-methylimidazole) (pfpO2), which was previously analyzed using L-edge XAS. The K-edge XAS and RIXS data of pfpO2 and oxyhemoglobin are compared with the data for low-spin FeII and FeIII [Fe(tpp)(Im)2]0/+ (tpp = tetra-phenyl porphyrin) compounds, which serve as heme references. The X-ray data show that pfpO2 is similar to FeII, while oxyhemoglobin is qualitatively similar to FeIII, but with significant quantitative differences. Density-functional theory (DFT) calculations show that the difference between pfpO2 and oxyhemoglobin is due to a distal histidine H bond to O2 and the less hydrophobic environment in the protein, which lead to more backbonding into the O2. A valence bond configuration interaction multiplet model is used to analyze the RIXS data and show that pfpO2 is dominantly FeII with 6–8% FeIII character, while oxyhemoglobin has a very mixed wave function that has 50–77% FeIII character and a partially polarized Fe–O2 π-bond.

The electronic structure of the active sites in oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) and oxymyoglobin has been the subject of study and debate for decades. The iron oxygen-binding proteins contain an S = 0 {FeO2}8 active site, denoting eight valence electrons delocalized among the Fe 3d and O2 π*-orbitals in the Enemark–Feltham (1) notation used for metal–NO complexes. Three electronic structure models have been proposed by Pauling and Coryell (2, 3) (low-spin FeII with singlet O2), Weiss (4) (low-spin FeIII antiferromagnetically coupled to doublet O2−), and McClure (5), Harcourt (6, 7), and Goddard and Olafson (8) (S = 1 FeII antiferromagnetically coupled to triplet O2, also known as the “ozone” model). Much computational work has been done, with all three models supported by different calculations (9–13). However, there has been a dearth of experimental data to directly probe the electronic structure. In particular, the intense porphyrin π → π* transitions of heme complexes make it difficult to probe the highly covalent Fe with traditional spectroscopic methods (14, 15).

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), a site-specific technique that provides a direct probe of the metal center, has added to the controversy. An analysis of the iron K preedge suggested that HbO2 has an electronic structure similar to the Weiss model in solution, but that crystalline HbO2 has an electronic structure more similar to the Pauling model (16). Alternatively, a recent X-ray emission Kβ study suggested that the iron center has an S = 1 FeII spin state, similar to the ozone model (17). However, neither technique provides a quantitative analysis of the electronic structure of iron centers. In contrast, L-edge XAS measures the electric-dipole-allowed metal 2p → 3d transitions, where the integrated intensity is proportional to the total amount of metal 3d character in the valence orbitals (18). This makes the technique powerful in studying highly covalent metal sites. Quantitative covalency information can be extracted through modeling of the L-edge XAS spectra using a valence bond configuration interaction (VBCI) multiplet model (19). This methodology has been applied to iron complexes to extract the differential orbital covalency (DOC), which allows for quantification of ligand σ- and π-donation (18, 20, 21) and metal π-backbonding (22), including in heme models (14)

L-edge XAS and the VBCI multiplet model were used to analyze the S = 0 {FeO2}8 heme model compound [(pfp)Fe(1-MeIm)(O2)] [pfp = meso-tetra(α,α,α,α-o-pivalamido-phenyl)porphyrin, 1-MeIm = 1-methylimidazole] (pfpO2) (23). That study determined that the pfpO2 model compound had an electronic structure more similar to the Pauling model. The pfpO2 compound has been seen as a good model for HbO2, with similar vibrational (24–27) and Mössbauer spectra (28–33). One major difference between the model complex and the protein is that the protein has a conserved histidine in the active site that can hydrogen-bond to the O2. This hydrogen bond has been calculated by Shaik and coworkers (9) to be important in modulating the electronic structure of oxymyoglobin, leading to a more polarized Weiss-like description. It is therefore important to experimentally compare the pfpO2 model compound with the HbO2 protein.

One major limitation of iron L-edge XAS is that it occurs in the soft X-ray regime (∼710 eV), which requires ultrahigh vacuum that limits the measurement of protein or solution samples. However, “L-edge–like” information can be obtained through 1s2p resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) (34). The 1s2p RIXS involves a two-step process, where a hard (∼7,100-eV) X-ray incident photon of energy Ω causes a 1s → 3d transition, followed by 2p → 1s decay, releasing a photon of energy ω (35, 36). The resulting 2p53dn+1 final-state configuration is the same as for L-edge XAS, which can be simulated with the VBCI multiplet model to extract the DOC and provide a quantitative bonding description (37). The 1s2p RIXS can therefore be used to directly compare protein and model compounds. It is a complementary technique to L-edge XAS and the differences between L-edge XAS and 1s2p RIXS have been previously studied with several nonheme iron model compounds (38).

A combined L-edge XAS and 1s2p RIXS methodology was developed and applied to study the bonding in ferrous and ferric cytochrome c (39). This involved an initial analysis of heme model compounds that could be measured by both L-edge XAS and 1s2p RIXS, which allowed for calibration of the VBCI model between the two techniques. The 1s2p RIXS analysis of the model compound was then used to calibrate the 1s2p RIXS analysis of the protein system, where L-edge XAS data were unavailable. This methodology is applied in the present study, by first studying the 1s2p RIXS of pfpO2, for which the L-edge XAS analysis has been done, and then using this model as a reference for the analysis of the 1s2p RIXS of HbO2.

Results and Analysis

RIXS Planes.

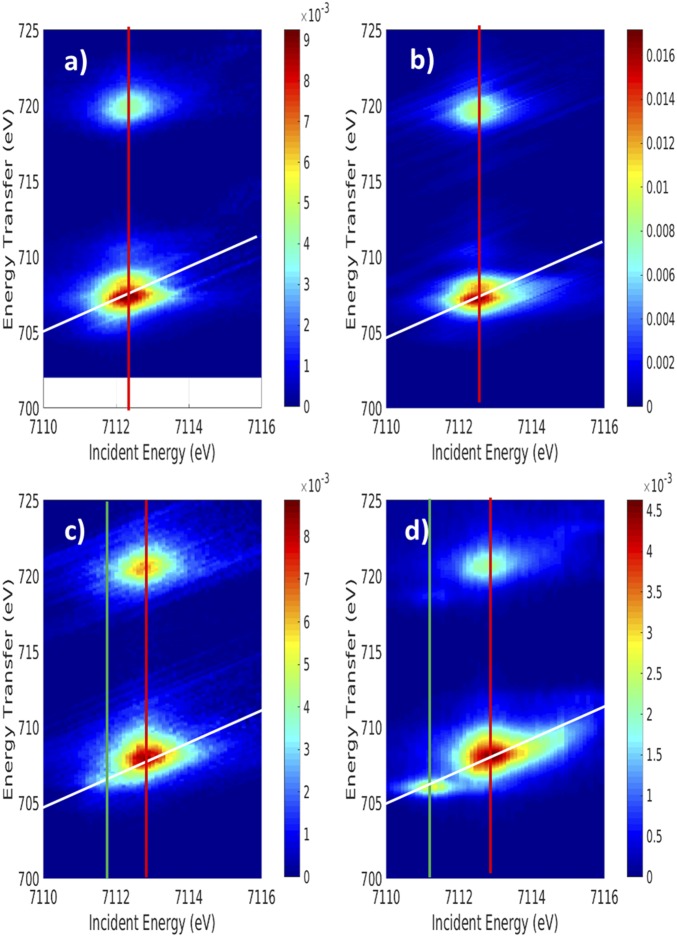

The two-dimensional background-subtracted RIXS data for both pfpO2 and HbO2 are shown in Fig. 1 B and C, respectively, along with the RIXS planes of [FeII(tpp)(ImH)2] (Fe2tpp, Fig. 1A) and [FeIII(tpp)(ImH)2]+ (Fe3tpp, Fig. 1D) included as references for low-spin FeII and low-spin FeIII in porphyrin environments (large version in SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The RIXS planes for pfpO2 and HbO2 exhibit clear differences. The pfpO2 plane has only a single incident energy resonance (x axis) at 7,112.2 eV. The main L3 feature of the resonance is broad along the energy transfer direction (Ω - ω, y axis) and resolves into two peaks, with the main peak at 707.2 eV and an intense shoulder at 708.3 eV. At higher energy, a low-intensity satellite feature also appears at ∼710 eV. The pattern of the RIXS plane of pfpO2, with a single incident energy resonance and a double-peak feature in the energy transfer direction, is very similar to the pattern of the RIXS plane of Fe2tpp (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Background-subtracted RIXS planes of (A) Fe2tpp, (B) pfpO2, (C) HbO2, and (D) Fe3tpp. The diagonal white lines represent where CEE cuts were made. The vertical red and green lines represent where CIE cuts were made.

Unlike pfpO2, HbO2 clearly shows two incident energy resonances, with a small, weak feature at 7,111.4 eV, and a large, broad feature at 7,112.8 eV. The 7,112.8-eV resonance does not exhibit the double-peak feature seen in the pfpO2 and Fe2tpp planes. The HbO2 RIXS plane is not only different from the low-spin FeII reference plane, but is also very different from the low-spin FeIII reference plane (Fig. 1D). The “dπ”-resonance (7,111.3 eV) in the Fe3tpp plane is higher in intensity than the low-energy resonance in HbO2 and is also further separated in energy from the main peak (7,112.9 eV) in the energy transfer direction. For Fe3tpp, the low-energy peak of the L3 occurs at 706 eV in the energy transfer direction, with the main peak at 708 eV, compared with 706.5 and 708 eV, respectively, in HbO2. From the comparison of the RIXS planes, pfpO2 experimentally appears very similar to Fe2tpp, while HbO2 appears more “ferric-like” than pfpO2, but significantly less than Fe3tpp.

Constant Emission Energy Cuts and K-Edge Spectroscopy.

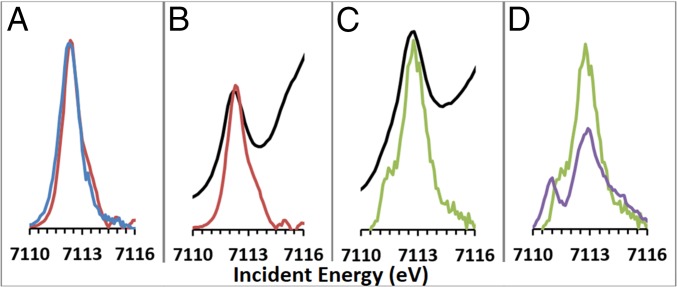

The K-edge spectra of pfpO2 and HbO2 are shown in Fig. 2 B and C, along with comparisons to the corresponding constant emission energy (CEE) cuts (full K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure in SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The CEE cuts were made through the maxima of the RIXS planes and are marked by the diagonal white lines through the planes in Fig. 1. The integrated intensity of the pfpO2 preedge is 4.1 units, while the HbO2 preedge is more intense at 6.7 units. The pfpO2 preedge intensity is comparable to the preedge intensities of other six-coordinate low-spin ferrous and ferric compounds (three to five units) (40), including Fe2tpp (4.9) and Fe3tpp (4.3). While HbO2 has a more intense preedge than the other compounds, it is still significantly lower in intensity than the preedge intensities of distorted six-coordinate protein active sites (∼8 units) (41) and of four-coordinate tetrahedral and square pyramidal five-coordinate compounds (11+ units). The latter have significant electric-dipole intensity due to 4p mixing caused by loss of inversion symmetry (40). This means that the preedge features of pfpO2 are primarily due to 1s → 3d quadrupole excitations, but HbO2 has a small amount of dipole intensity due to limited distortion at the Fe center.

Fig. 2.

(A) Comparison of CEE cut of pfpO2 (red) with Fe2tpp (blue). (B) Comparison of K-edge spectrum of pfpO2 (black) with CEE cut (red). (C) Comparison of K-edge spectrum of HbO2 (black) with CEE cut (green). (D) Comparison of CEE cut of HbO2 (green) with Fe3tpp (purple).

In comparing the K edges with the CEE cuts in Fig. 2 B and C, the main insight is that the CEE cuts in red and green provide a higher-energy-resolution K edge. In the CEE cut of pfpO2, there is a single preedge peak, as in the K edge, but with a higher energy shoulder. This shoulder is not due to a new 1s → 3d excitation, but is due to overlap with the feature in the preedge that occurs at the same incident energy, but higher energy transfer in Fig. 1B. This phenomenon was noted in our previous RIXS studies and emphasizes the need to collect the full 2D RIXS plane to analyze these data (38).

The high-resolution CEE cut of HbO2 clearly shows two peaks, with a small peak at lower incident energy (Fig. 2C). This peak is much less clear in the K edge, where analysis of the second derivative is necessary to confirm the presence of the peak. The CEE cuts emphasize the differences between pfpO2 and HbO2 seen in the RIXS planes. To compare cuts between the different samples, cuts were scaled such that the RIXS preedge integrated intensity was the same as that obtained through K-edge XAS. The pfpO2 CEE cut is very similar to the CEE cut of Fe2tpp (Fig. 2A). The HbO2 CEE cut is very different from that of Fe3tpp (Fig. 2D). While the lower-energy peak appears comparable in intensity to that in Fe3tpp, the energy splitting between the low-energy peak and the main peak is much smaller. The main peak in HbO2 is also much more intense than in Fe3tpp. From the crystal structures of HbO2, the Fe–O2 bond length is ∼1.8 Å, compared with ∼2 Å for the other bonds (42). This would lead to 4pz mixing with dz2, which would increase the intensity in the main peak (40). Although HbO2 displays two peaks in its CEE cut, it has significant and quantitative differences from the low-spin ferric reference spectrum.

Constant Incident Energy Cuts and L-Edge Spectroscopy.

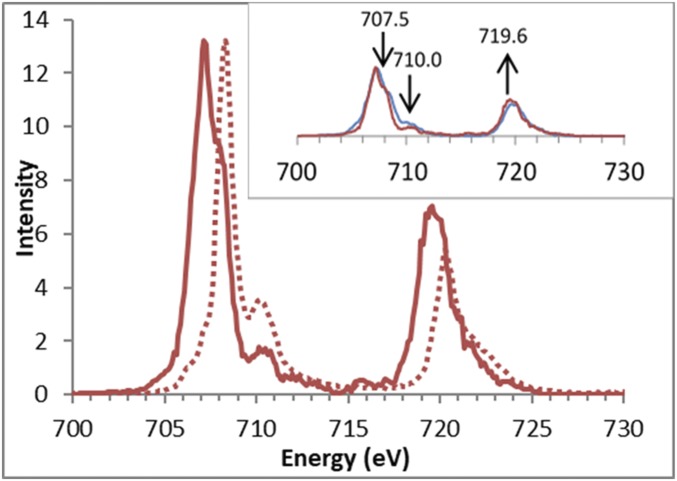

The L-edge spectrum of pfpO2 was analyzed in a previous study (23) and is compared with the constant incident energy (CIE) cut through the maximum of the RIXS preedge in Fig. 3. The CIE is given by the red vertical lines in Fig. 1. Unlike the L-edge spectrum (dotted), which has one prominent peak in the L3 region, the CIE cut has a broad double peak, with the lower-energy peak being higher in intensity. The higher-energy satellite feature, at ∼710 eV, is higher in intensity in the L-edge spectrum compared with the CIE cut. The L2 region of the CIE cut is also higher in intensity compared with the L-edge spectrum. Fig. 3 (Inset) shows a comparison of the CIE cut of pfpO2 with the CIE cut of Fe2tpp. The cuts are qualitatively very similar, with both showing a broad double-peak main feature in the L3 region. There are however several notable differences between the two cuts, with the pfpO2 cut having less intensity in the region at ∼707.5 eV and in the higher-energy satellite feature at ∼710 eV, but more intensity in the L2 region (∼720 eV), compared with the Fe2tpp cut. These differences are very similar to those previously observed comparing Fe2tpp to reduced cytochrome c, where there is also a change in the axial ligation (N to S) (39).

Fig. 3.

The CIE cut of pfpO2 at 7,112.2 eV (solid) with the L-edge spectrum (dotted). (Inset) Comparison of the CIE cut of pfpO2 (red) with Fe2tpp (blue). Arrows show where pfpO2 has different intensity from that of Fe2tpp.

For HbO2, there is no comparison between L-edge and RIXS CIE cuts, due to the limitations in acquiring L-edge spectra on proteins. The comparison of the CIE cuts through the maxima of the two resonances in HbO2 (given by the vertical lines in Fig. 1C) with the CIE cuts through the maxima of the two resonances in Fe3tpp is shown in Fig. 4. The most significant difference between the two datasets comes from the CIE cut through the low-energy dπ-peak (green). While the Fe3tpp cut (dotted) has a sharp, intense peak at 706 eV with some residual intensity from the main resonance at 708 eV, the HbO2 cut (solid) has a lower-intensity peak at 706.5 eV that is barely discernible from the residual intensity from the main resonance. In the CEE, the low-energy peaks appear comparable in intensity, but the CIE cuts clearly show that the HbO2 peak has lower intensity compared with Fe3tpp and has a smaller energy splitting between the low-energy peak and the main peak. The cuts through the main peak show similar shapes, but with HbO2 having higher intensity due to the dipole contribution (vide supra).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of CIE cuts of HbO2 (solid) and Fe3tpp (dotted). CIE cuts through the low-energy peaks (at 7,111.4 eV for HbO2 and 7,111.3 eV for Fe3tpp) are in green. CIE cuts through the main peaks (at 7,112.8 eV for HbO2 and 7,112.9 eV for Fe3tpp) are in red. The CIE cuts are scaled to match the RIXS and K preedge integrated intensities.

Thus, the RIXS data show significant differences between HbO2 and pfpO2. pfpO2 has spectral features qualitatively like that of the low-spin ferrous reference compound, while HbO2 has two incident energy resonances, similar to that of the low-spin ferric reference compound. However, the HbO2 spectrum has significant quantitative differences in peak energy and intensity compared with the Fe3tpp spectrum. The next section uses DFT calculations to gain insight into the origin of these differences. The electronic structures of pfpO2 and HbO2 are analyzed further with VBCI modeling of these different RIXS planes in the last section of the analysis.

DFT Calculations.

The RIXS data show significant differences between the electronic structures of HbO2 and pfpO2. To understand the source of these differences, DFT calculations were performed on these systems using the crystal structures as the starting geometries (42, 43), with toluene as the solvent in a polarized continuum model for pfpO2. For HbO2, the proximal histidine, which binds directly to the Fe, as well as the distal histidine, which can H-bond with the O2 and has been implicated in tuning the electronic structure of the site (9), were included in the calculation as full amino acid residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Additionally, a side-chain carbonyl that may H-bond with the proximal histidine was modeled using a formaldehyde (16), and a dielectric of 10 was used to model the protein environment. Geometry optimizations were performed on the starting structures using the BP86 functional. Single-point calculations with B3LYP and BP86 gave similar results (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). In all cases, a polarized electronic structure was found lowest in energy by a few kilocalories per mole. Full computational details can be found in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

The electronic structure results of the calculations are given in Table 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Table S1, along with calculations on Fe2tpp and Fe3tpp as reference compounds. The optimized structures of pfpO2 and HbO2 have very similar coordination environments around the Fe. The calculated electronic structures are also largely similar, with both having ∼344% total unoccupied metal 3d character in the valence orbitals (Table 1). This is to be compared with 346 and 313% for the Fe3tpp and Fe2tpp references, respectively. Thus, both are calculated to be closer to FeIII; however, the experimental L-edge XAS total d character for pfpO2 is closer to FeII. The main difference is found in the backbonding. While the total amount of backbonding of occupied Fe character into the porphyrin and O2 π* (Table 1) orbitals is the same for both complexes (∼93%, Table 1), the distribution of this metal character is different. pfpO2 has less backbonding into the O2 π* (68.8 vs. 76.2%), which is compensated by increased backbonding into the porphyrin π*-orbitals. This difference in Fe–O2 bonding explains the slightly longer Fe–O (1.83 vs. 1.82 Å) and shorter O–O (1.30 vs. 1.32 Å) calculated bonds in pfpO2 compared with HbO2 (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Table 1.

Amount of metal 3d character in the lowest unoccupied orbitals calculated using the BP86 functional with experimental values in parentheses

| Calculated % Metal 3d Character in Unoccupied Orbitals | |||||||||||

| Compound | σ, dz2 | σ, dx2−y2/x | π*, por† | π*, O2 | Total‡ | Total backbonding§ | O2 backbonding | ||||

| α | β | α | β | α | β | α | β | ||||

| Fe2tpp | 66.5 | 66.5 | 71.2 | 71.2 | 9.5 | 9.5 | N/A | N/A | 313.2 (302) | 37.8 | N/A |

| pfpO2 | 63.2 | 55.5 | 68.6 | 64.1 | 9.5 | 2.9 | 59.8 | 9.0 | 344.9 (310) | 93.5 | 68.8 |

| HbO2 | 61.3 | 56.7 | 68.1 | 63.6 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 64.4 | 11.8 | 342.7 | 93 | 76.2 |

| Fe3tpp | 66.5 | 63.3 | 67.2 | 62.8 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 70.9¶ | N/A | 346.2 (365) | 18.6 | N/A |

For Fe2tpp, the closed-shell solution was lowest in energy so α- and β-occupancies are the same

The metal values for the porphyrin π*-orbitals are an average of two different orbitals.

Experimental unoccupied 3d character comes from L-edge integrated intensity, which does not exist for HbO2.

Total backbonding includes backbonding to both O2 and porphyrin π*-orbitals and is the sum of metal character from the orbitals.

This value for Fe3tpp represents the metal character in the dπ-hole.

Based on the models used for the calculation, this difference in backbonding can be due to several factors: (i) the carbonyl H bond to the proximal histidine, (ii) the dielectric, (iii) the distal histidine H bond to the O2, and/or (iv) the different porphyrins (heme b vs. picket-fence porphyrin). These factors were investigated through perturbations to the HbO2 model (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Removing the carbonyl H bond to the proximal histidine in the calculation showed minimal effect (76.2 vs. 76.1% backbonding to O2) on the electronic structure, in contrast to previous calculations (16). Then lowering the dielectric constant from 10 (protein) to 2.4 (toluene) decreased the backbonding to O2 from 76.1 to 74.3%, while subsequent removal of the distal histidine further lowered the backbonding to 69.1%, similar to pfpO2. The latter effect has been described by Shaik and coworkers (9). Since this perturbed heme b model has the same bonding description as in pfp, these calculations show that this difference in porphyrin has minimal effect on the electronic structure, the primary effect coming from the distal histidine H bond to O2, and the less hydrophobic environment of the protein pocket.

The difference in backbonding to the O2 qualitatively explains the spectral differences between pfpO2 and HbO2 in the RIXS data. As seen in the VBCI modeling (vide infra), increased backbonding from the Fe into the O2 leads to a more polarized electronic structure associated with the appearance of the low-energy feature seen in the HbO2 RIXS plane. In comparing the pfpO2 and HbO2 calculations with those of Fe2tpp and Fe3tpp, both are more like Fe3tpp than Fe2tpp (SI Appendix, Fig. S5, Right and Left, respectively). The π-bonding into O2 leads to a low-energy α-hole with significant metal character (∼63%), like the dπ-hole in Fe3tpp (70.9%) (purple orbital α1 in SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The total unoccupied metal 3d character is also very close to that of Fe3tpp (346.2%), but not Fe2tpp (313.2%). This significantly contrasts the experimental XAS and RIXS data, which show that pfpO2 is more like Fe2tpp, and that HbO2, while having a preedge feature associated with spin polarization, is still significantly different from Fe3tpp (vide supra). Time-dependent-DFT calculations were also performed, which also show that the HbO2 and pfpO2 calculations are more ferric-like than seen experimentally (SI Appendix, SI TD-DFT Analysis).

VBCI Modeling.

Since the DFT calculations provide a spin-polarized electronic structure description for both pfpO2 and HbO2 that have more ferric character than the experimental data suggest, a semiempirical VBCI multiplet model was used to fit the RIXS data to lock in on the electronic structure of the two compounds. The VBCI model provides a quantitative measure of the DOC in a metal complex by mixing the ground 3dn configuration with ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) (3dn+1L, L = ligand hole) and metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) (3dn−1L−) configurations. The weight of the configurations in the mixed wave function depends on the relative energy of the configurations (Δ) and the strength of the mixing (T).

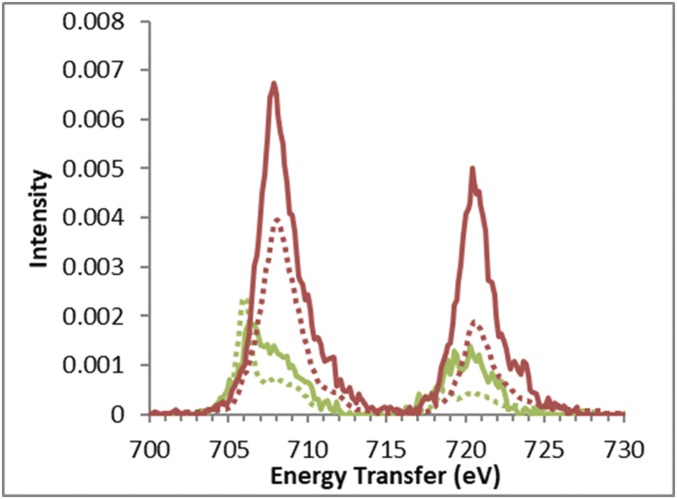

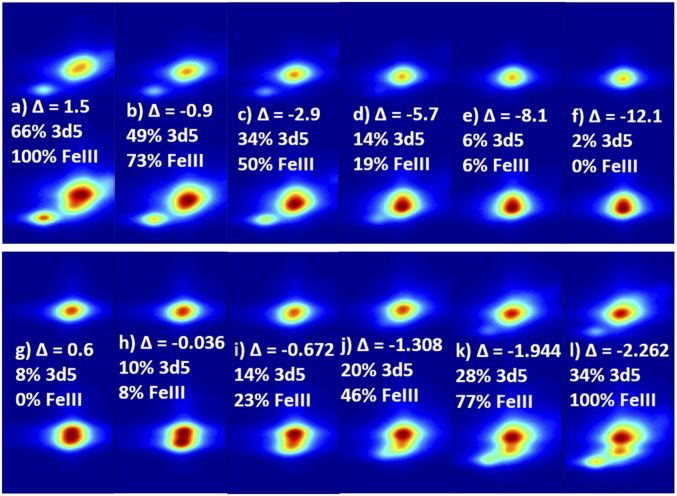

Previous studies have shown that by varying the weights of the charge-transfer configurations, it is possible to simulate ferrous (and ferric) L-edge spectra using both a ferric and a ferrous ground configuration (22, 23). This approach can be applied to 1s2p RIXS simulations as well. Fig. 5, Top shows a series of RIXS simulations, starting with the low-spin ferric simulation of Fe3tpp (Fig. 5A). In the Fe3tpp simulation, the energy difference between the LMCT (3d6) configuration and the ground (3d5) configuration, Δ, is 1.5 eV. As Δ decreases, the weight of the LMCT configuration increases and the wave function gains more ferrous character, becoming 2% 3d5 (Fig. 5F). The low-energy dπ-peak also decreases in intensity and shifts up in energy, eventually merging into the main peak in Fig. 5E.

Fig. 5.

(Top) VBCI RIXS simulations progressing from FeIII → FeII using the ferric 3d5 ground configuration, starting with the fit for Fe3tpp in A, with fits for HbO2 (C), pfpO2 (E), and Fe2tpp (F). In this series, Δ is decreased from 1.5 in A, to −12.1 in F, decreasing the weight of the 3d5 configuration and becoming dominantly 3d6. (Bottom) VBCI RIXS simulations progressing from FeII → FeIII using the ferrous 3d6 ground configuration, starting with the fit for Fe2tpp in G, with fits for pfpO2 (H), HbO2 (K), and Fe3tpp (L). Full fit parameters for Fe2tpp and Fe3tpp can be found in SI Appendix, Table S2. In this series, Δbb is decreased from 0.6 in G, to −2.262 in L. Simulations in B, D, I, and J do not correspond to any particular piece of experimental data.

Fig. 5, Bottom shows a series of RIXS simulations, starting with the low-spin ferrous simulation of Fe2tpp on the left. In this series, the energy difference between the MLCT (3d5) and ground (3d6) configurations, Δbb, is decreased going from left to right. As the weight of the MLCT configuration increases, the wave function gains more ferric character, and a low-energy dπ-peak appears in Fig. 5J, which gains in intensity and moves to lower energy. Correlation of these simulations to the HbO2 data, which have a low-intensity dπ-peak close in energy to the main peak (Figs. 1 and 2), show that they can be simulated as a mixed wave function of low-spin 3d6 and 3d5 configurations; thus, qualitatively it can either be described as a low-spin ferric site with strong π-donation into the dπ-hole, or a low-spin ferrous center with extensive π-backbonding into the O2.

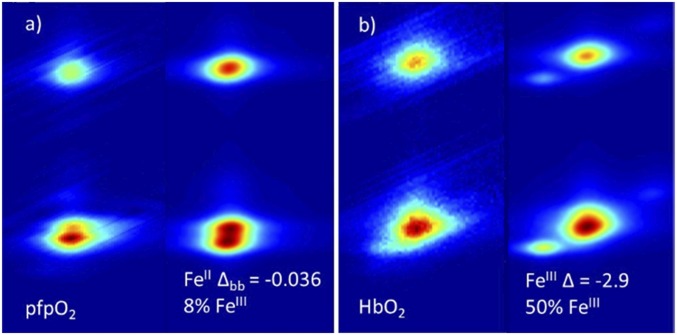

By fitting the Fe2tpp, pfpO2, HbO2, and Fe3tpp data along the FeIII → FeII (Fig. 5, Top) and FeII → FeIII (Fig. 5, Bottom) series, the amount of FeII/FeIII character in each system can be estimated to obtain a more quantitative description of the electronic structure. The simulated integrated CEE and CIE were compared with the experimental data to find the best match within a series (SI Appendix, Figs. S7–S10 and Table S3). Since the VBCI model only calculates quadrupole intensity, it is directly comparable to the pfpO2, Fe2tpp, and Fe3tpp datasets. However, because the HbO2 contains some dipole intensity in the main peak, the intensity and energy splitting of the low-energy peak (in both the CIE and CEE) is the primary handle for comparing the VBCI simulations to the experimental data. The Fe2tpp and Fe3tpp fits were used as FeII and FeIII limits (39), representing 0 and 100% “FeIII” character, respectively. The first limit corresponds to 2% 3d5 character and the second limit to 66% 3d5 character. The difference between FeIII and 3d5 character comes from ligand donation and backdonation present already in the reference complexes. The FeIII character for pfpO2 and HbO2 were then defined relative to those references (SI Appendix, SI VBCI Fitting). The resulting fits (Fig. 6) show that along the FeIII → FeII series, pfpO2 has 6% FeIII character, while HbO2 has 50% FeIII character. In the FeII → FeIII series, pfpO2 has 8% FeIII character, while HbO2 has 77% FeIII character. Thus, the fitting shows that pfpO2 is dominantly FeII, and that HbO2 has a very mixed FeII/FeIII wave function that has more FeIII character.

Fig. 6.

Best VBCI fits from the simulations described in Fig. 5 for (A) pfpO2 and (B) HbO2 with the experimental data on the left, and the fit on the right. Since the results showed that pfpO2 is dominantly FeII, the FeII fit is given. In the case of HbO2, the results showed a mixed wave function that is more FeIII, and therefore the FeIII fit is given.

Discussion

From the VBCI modeling of the 1s2p RIXS data, HbO2 is best described as a polarized mixed FeII/FeIII system that has 50–77% FeIII character. This contrasts with pfpO2, which is best described as an unpolarized FeII with 6–8% FeIII character. The modeling also shows that the difference in electronic structure can be attributed to the covalency of the Fe–O2 π-bond. HbO2 has significantly more FeIII character than pfpO2 because of greater π-backbonding to O2. These results combined with DFT definitively show the stark difference between HbO2 and its “good” model, pfpO2, due to the distal histidine H bond to the O2 combined with the less hydrophobic protein environment. Both are important in polarizing the Fe–O2 π-bond. In previous studies on {FeNO}6, it was found that the degree of polarization is governed by the magnitude of the energy gap of the Fe–NO π-bonding and antibonding orbitals relative to the strength of the exchange interaction between electrons in these orbitals (44). When the energy gap is large relative to the exchange interaction, the bond remains unpolarized. As the energy gap decreases, the wave function becomes more polarized (SI Appendix, Scheme S1). pfpO2 thus has a large enough energy gap to result in an unpolarized bonding description. The addition of the H bond and increased dielectric in the protein stabilize the O2 π*-orbital energy, which leads to polarization of the Fe–O2 π-bond and the appearance of a low-energy peak in the RIXS spectrum in Fig. 1C.

These electronic structure descriptions, unpolarized FeII for pfpO2 and mixed FeII/FeIII for HbO2 due to greater π-backbonding into O2 are consistent with other experimental data. L-edge XAS provided evidence that pfpO2 is an unpolarized FeII with moderate backbonding to O2 (23). The K edge of HbO2 is shifted slightly higher in energy compared with pfpO2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), and both are between Fe2tpp and Fe3tpp, with pfpO2 closer to Fe2tpp and HbO2 closer to Fe3tpp. Although previous iron Kβ measurements on HbO2 and oxymyoglobin suggested the iron is S = 1 based on the high intensity of a satellite peak at ∼7,045 eV, we have measured the Kβ spectrum of the HbO2 sample used here and found a significantly weaker satellite feature that is not consistent with an S = 1 Fe (SI Appendix, Fig. S15) (17). The FeII S = 1 description of HbO2 also requires polarized Fe–O π-backbonding and polarized O–Fe σ-donation. Attempts to use the VBCI multiplet model to simulate the experimental RIXS data using this description were unsuccessful. The RIXS analysis is also consistent with previous vibrational and Mössbauer spectroscopic studies. Those methods have been used to describe pfpO2 and HbO2 as similar and FeIII. However, alternative interpretations also agree with the X-ray results showing less FeIII character (SI Appendix, Discussion on {FeO2}8O-O Stretching Frequencies and Mössbauer Parameters).

These results also provide an experimental basis for further calculations. As observed in the previous section, DFT calculations provide a poor description of these oxy-Fe sites. DFT is a single-determinant method and gives ferric descriptions, while the data indicate more ferrous character. Multireference methods, such as complete active space self-consistent field, are best to correlate to these data. Importantly, the experimental data show the H bond and protein environment have a large effect on the {FeO2}8 electronic structure, inducing some polarization in the Fe–O2 π-bond. These RIXS data on the electronic structure of oxyhemoglobin and its pfp model should provide the experimental basis for more detailed electronic structure considerations.

Materials and Methods

Oxy–picket-fence porphyrin samples were prepared as described in ref. 31. Hemoglobin samples were prepared as described in ref. 16. K-edge XAS data were collected at beam line 7–3 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). RIXS data were collected at beam line 6–2 at SSRL and ID-26 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. VBCI modeling was performed using the models developed by Cowan (45) and Thole et al. (46) DFT calculations were performed using the Orca 3.0.3 software package (47). Full details on sample preparation, spectroscopic experiments, and calculations are included in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM-40392 to E.I.S.). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant P41GM103393 to K.O.H and B.H). T.K. acknowledges financial support by the German Research Foundation (DFG) Grant KR3611/2-1. M.L.B. acknowledges the support of the Human Frontier Science Program. M.L. acknowledges support from the Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1815981116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Enemark JH, Feltham RD. Principles of structure, bonding, and reactivity for metal nitrosyl complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 1974;13:339–406. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauling L, Coryell CD. The magnetic properties and structure of hemoglobin, oxyhemoglobin and carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1936;22:210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauling L. Nature of the iron-oxygen bond in oxyhaemoglobin. Nature. 1964;203:182–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss JJ. Nature of the iron-oxygen bond in oxyhaemoglobin. Nature. 1964;202:83–84. doi: 10.1038/202083b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClure DS. Electronic structure of transition-metal complex ions. Radiat Res Suppl. 1960;2:218–242. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harcourt RD. Increased-valence formulae and the bonding of oxygen to haemoglobin. Int J Quantum Chem. 1971;5:479–495. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harcourt RD. Comment on a CASSCF study of the Fe-O2 bond in a dioxygen heme complex. Chem Phys Lett. 1990;167:374–377. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goddard WA, 3rd, Olafson BD. Ozone model for bonding of an O2 to heme in oxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2335–2339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Ikeda-Saito M, Shaik S. Nature of the Fe-O2 bonding in oxy-myoglobin: Effect of the protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14778–14790. doi: 10.1021/ja805434m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao M-S, Huang M-J, Watts JD. Iron porphyrins with different imidazole ligands. A theoretical comparative study. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:9554–9569. doi: 10.1021/jp1052216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attia AAA, Lupan A, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. Spin state preference and bond formation/cleavage barriers in ferrous-dioxygen heme adducts: Remarkable dependence on methodology. RSC Adv. 2013;3:26194–26204. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepp KP, Dasmeh P. Effect of distal interactions on O2 binding to heme. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:3755–3770. doi: 10.1021/jp400260u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen KP, Ryde U. How O2 binds to heme: Reasons for rapid binding and spin inversion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14561–14569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hocking RK, et al. Fe L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy of low-spin heme relative to non-heme Fe complexes: Delocalization of Fe d-electrons into the porphyrin ligand. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:113–125. doi: 10.1021/ja065627h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bren KL, Eisenberg R, Gray HB. Discovery of the magnetic behavior of hemoglobin: A beginning of bioinorganic chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13123–13127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515704112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SA, et al. X-ray absorption spectroscopic investigation of the electronic structure differences in solution and crystalline oxyhemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16333–16338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315734110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuth N, et al. Effective intermediate-spin iron in O2-transporting heme proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:8556–8561, and erratum (2017) 114:E8129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706527114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasinger EC, de Groot FMF, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy of non-heme iron sites: Experimental determination of differential orbital covalency. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12894–12906. doi: 10.1021/ja034634s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker ML, et al. K- and L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) determination of differential orbital covalency (DOC) of transition metal sites. Coord Chem Rev. 2017;345:182–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hocking RK, et al. Fe L- and K-edge XAS of low-spin ferric corrole: Bonding and reactivity relative to low-spin ferric porphyrin. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:1678–1688. doi: 10.1021/ic802248t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hocking RK, et al. Fe L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy determination of differential orbital covalency of siderophore model compounds: Electronic structure contributions to high stability constants. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4006–4015. doi: 10.1021/ja9090098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hocking RK, et al. Fe L-edge XAS studies of K4[Fe(CN)6] and K3[Fe(CN)6]: A direct probe of back-bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10442–10451. doi: 10.1021/ja061802i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson SA, et al. Iron L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy of oxy-picket fence porphyrin: Experimental insight into Fe-O2 bonding. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1124–1136. doi: 10.1021/ja3103583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow CH, Maxwell JC, Wallace WJ, Caughey WS. Elucidation of the mode of binding of oxygen to iron in oxyhemoglobin by infrared spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;55:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(73)80063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell JC, Volpe JA, Barlow CH, Caughey WS. Infrared evidence for the mode of binding of oxygen to iron of myoglobin from heart muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;58:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90906-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potter WT, Tucker MP, Houtchens RA, Caughey WS. Oxygen infrared spectra of oxyhemoglobins and oxymyoglobins. Evidence of two major liganded O2 structures. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4699–4707. doi: 10.1021/bi00389a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collman JP, Brauman JI, Halbert TR, Suslick KS. Nature of O2 and CO binding to metalloporphyrins and heme proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3333–3337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai TE, Groves JL, Wu CS. Electronic structure of iron–dioxygen bond in oxy‐Hb‐A and its isolated oxy‐α and oxy‐β chains. J Chem Phys. 1981;74:4306–4314. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boso B, Debrunner PG, Wagner GC, Inubushi T. High-field, variable-temperature Mössbauer effect measurement on oxyhemeproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;791:244–251. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshtrakh MI, et al. Heme iron state in various oxyhemoglobins probed using Mössbauer spectroscopy with a high velocity resolution. Biometals. 2011;24:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spartalian K, Lang G, Collman JP, Gagne RR, Reed CA. Mössbauer spectroscopy of hemoglobin model compounds: Evidence for conformational excitation. J Chem Phys. 1975;63:5375–5382. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collman JP, et al. Synthesis and characterization of “tailed picket fence” porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4182–4192. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Noll BC, Oliver AG, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. Correlated ligand dynamics in oxyiron picket fence porphyrins: Structural and mössbauer investigations. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15627–15641. doi: 10.1021/ja408431z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glatzel P, Bergmann U. High resolution 1s core hole X-ray spectroscopy in 3d transition metal complexes—Electronic and structural information. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:65–95. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glatzel P, et al. The electronic structure of Mn in oxides, coordination complexes, and the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II studied by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9946–9959. doi: 10.1021/ja038579z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Groot FMF, et al. 1s2p resonant inelastic X-ray scattering of iron oxides. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:20751–20762. doi: 10.1021/jp054006s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroll T, Lundberg M, Solomon EI. X-Ray Absorption and RIXS on Coordination Complexes. X-Ray Absorption and X-Ray Emission Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2016. pp. 407–435. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundberg M, et al. Metal-ligand covalency of iron complexes from high-resolution resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17121–17134. doi: 10.1021/ja408072q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroll T, et al. Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering on ferrous and ferric bis-imidazole porphyrin and cytochrome c: Nature and role of the axial methionine-Fe bond. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:18087–18099. doi: 10.1021/ja5100367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westre TE, et al. A multiplet analysis of Fe K-edge 1s → 3d pre-edge features of iron complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6297–6314. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasinger EC, et al. X-ray absorption spectroscopic investigation of the resting ferrous and cosubstrate-bound active sites of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6211–6217. doi: 10.1021/bi0121510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S-Y, Yokoyama T, Shibayama N, Shiro Y, Tame JRH. 1.25 A resolution crystal structures of human haemoglobin in the oxy, deoxy and carbonmonoxy forms. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jameson GB, et al. Structure of a dioxygen adduct of (1-methylimidazole)-meso-tetrakis(α,α,-o-pivalamidophenyl)porphinatoiron(II). An iron dioxygen model for the heme component of oxymyoglobin. Inorg Chem. 1978;17:850–857. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan JJ, et al. L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopic investigation of FeNO6: Delocalization vs antiferromagnetic coupling. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:1215–1225. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowan RD. 1981. The Theory of Atomic Structure and Spectra (Univ of California Press, Berkeley, CA), p xviii.

- 46.Thole BT, et al. 3d x-ray-absorption lines and the 3d94fn+1 multiplets of the lanthanides. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1985;32:5107–5118. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.32.5107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank N. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.