Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in well-known, significant alterations in structural and functional connectivity. Although this is especially likely to occur in areas of pathology, deficits in function to and from remotely connected brain areas, or diaschisis, also occur as a consequence to local deficits. As a result, consideration of the network wiring of the brain may be required to design the most efficacious rehabilitation therapy to target specific functional networks to improve outcome. In this work, we model remote connections after controlled cortical impact injury (CCI) in the rat through the effect of callosal deafferentation to the opposite, contralesional cortex. We show rescue of significantly reaching deficits in injury-affected forelimb function if temporary, neuromodulatory silencing of contralesional cortex function is conducted at 1 week post-injury using the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist muscimol, compared with vehicle. This indicates that subacute, injury-induced remote circuit modifications are likely to prevent normal ipsilesional control over limb function. However, by conducting temporary contralesional cortex silencing in the same injured rats at 4 weeks post-injury, injury-affected limb function either remains unaffected and deficient or is worsened, indicating that circuit modifications are more permanently controlled or at least influenced by the contralesional cortex at extended post-injury times. We provide functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of the neuromodulatory effect of muscimol on forelimb-evoked function in the cortex. We discuss these findings in light of known changes in cortical connectivity and excitability that occur in this injury model, and postulate a mechanism to explain these findings.

Keywords: contralesional cortex, fMRI, muscimol, somatosensory cortex, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The current absence of any FDA-approved pharmacological treatment to intervene after traumatic brain injury (TBI) leaves neurorehabilitation as the only currently available clinical approach for enhancement of function. Despite the well-known impact of neurorehabilitation after central nervous system (CNS) injury,1 the potential for improving the clinical efficacy of neurorehabilitation approaches remains relatively less well-known or untested. This is likely due to a multitude of factors, but can certainly be ascribed to numerous factors including: the difficulty in testing new procedures on the acutely brain-injured patient, the relative heterogeneous types of injuries among victims, as well as the ethical implications in recruiting injured subjects who receive little or no rehabilitation for use as appropriate controls. Yet many questions remain to be answered with regard to time, intensity, and duration of intervention and whether brain-region–specific, focused training is useful in improving outcome.

From a solely brain-centric viewpoint, it remains uncertain which brain regions to focus on after injury to elicit greater functional improvements. At least experimentally, there are questions with regard to whether regions remote from the major areas of injury, for example the less injured hemisphere, should be treated differently from the site of primary injury.2 Although in our own research on the rat controlled cortical impact (CCI) model of TBI we have found the expected deficits in both structural and functional connectivity in the primary cortical injury site, we have also found significant increases in connectivity, especially in remote regions such as thalamus and contralesional hemisphere,3 similar to very detailed blood-flow connectivity data obtained by autoradiography after CCI.4 These remote changes in contralesional connectivity along with an early imbalance in cortical excitability5 suggest that there is a hemispheric imbalance in brain function, making remote areas potentially important effectors for reorganization of functional circuits involving regions more directly affected by the primary injury. An early autoradiographic study in the CCI-injured rat provided good evidence for this by showing an absence of affected limb-evoked blood-flow changes in ipsilesional regions, but a gain of function in remote contralesional regions.6 In fact, more recent data in the same model confirmed these effects using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and c-FOS immunohistochemistry, and showed that this was accompanied by increasing cortical excitation that developed by 4 weeks post-injury.7 Despite these compelling data implicating the involvement of connected, remote regions in recovery of function, they have never been causally shown to be crucial to spontaneous reorganization that is presumed to underlie much of functional outcome after TBI.

There is a large literature describing evidence of remote contralesional cortex involvement in limb function after lateralized brain injury such as stroke and other focal cortical lesion studies.8–13 However, the different mechanism of injury and in some cases difference in remote pathology,14,15 may not make the findings easily translatable to TBI, especially because far less is known about its role after unilateral CCI injury. In particular, the contralesional cortex has been found to lack the compensatory structural changes normally present after stroke,14 yet has been shown to be robustly activated compared with sham controls after CCI inury.4,6 To explore these apparent disparate changes, we hypothesized that silencing the homotopic cortical regions opposite the primary injury site at different times after injury would allow us to causally determine whether remote cortical circuits are involved in functional recovery after TBI. Herein we use the term cortical silencing only with regard to limiting neural activity governing forelimb function through using cortical infusion of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor agonist muscimol, rather than relating it directly to total neural activity within cortex. Musicmol has been shown to reduce post-synaptic neuronal activity16 within a limited radius in cortex17 and with a time-course for a reduction to 50% concentration of ∼30 min and to 10% by 2 h post-injection.17 We used the adult rat CCI injury model to produce a primary injury centered over the forelimb sensory and motor cortices and recorded bilateral forelimb reaching behavior after inactivating contralesional cortex at 1 and 4 weeks after injury using muscimol. We confirmed cortical inactivation in a separate cohort of injured rats using forelimb-evoked functional MRI (fMRI). These post-injury times were chosen to test whether behavioral gains could be made at 1 week at a time when the injury-affected limb cortical map is shifted trans-hemispherically,7 and at 4 weeks when map plasticity is more stable and when contralesional hyperexcitability has been found.7 We have previously shown that this injury model results in progressive alterations in white matter pathology that is rather more widespread than the dogma on its focal nature would suggest.18 Motor deficits are a significant and understudied problem in clinical TBI,19,20 and are presumably related to alterations in function among a variety of brain-wide networks, rather than being merely based on more focal deficits classically associated with the CCI injury model. Herein, rather than using the unilateral CCI model as a direct clinical simulation of such deficits, we merely use it to model local versus distant effects on circuits directly related to behavioral dysfunction. We show that acute post-injury inactivation of the contralesional cortex rescues affected forelimb reaching to pre-injury levels, whereas delayed inactivation conducted after affected forelimb recovery has occurred reinstates reaching deficits. We discuss these causative data together with prior correlative evidence from the same model that suggests a temporal window exists for circuit remodeling after injury beyond which function is less malleable.

Methods

Experimental groups and procedure

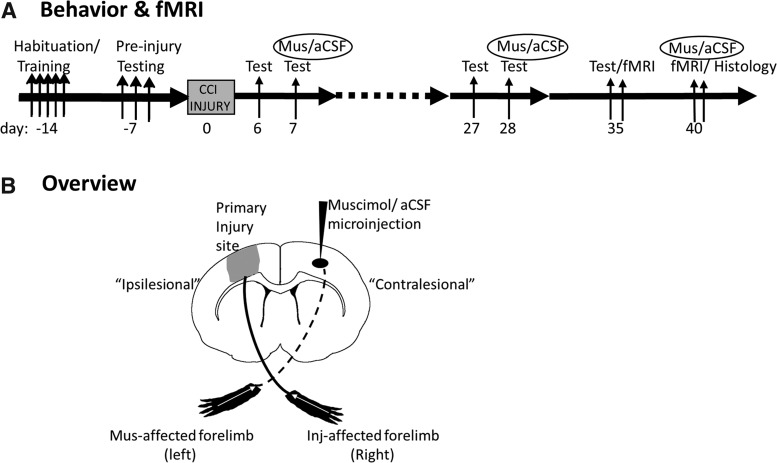

Two cohorts of adult, naïve, male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 21) were food-restricted (15 g/day) and received bilateral forelimb reach training and pre-injury testing on a staircase reaching task.21 After CCI injury over the left forelimb cortex, forelimb function was assessed prior to, and immediately after pharmacologically silencing the contralesional (right) forelimb cortex at 7 days and 28 days post-injury by infusion of muscimol (n = 13) or its vehicle, artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; n = 8, Fig. 1A). From the total two cohorts of rats, a subset (n = 7/group) was also tested at 35 days post-injury to determine if temporary silencing produced any lasting effects on limb function, and was then used to determine contusion size by histology at 40 days. A number of these injured rats (11 muscimol-injected, 3 aCSF-injected) were used to confirm right cortical inactivation due to muscimol after behavior at 5–6 weeks post-injury by recording fMRI activation data elicited by electrical stimulation of the left forelimb before and after brain infusion (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Experimental overview. (A) Time line of the experimental paradigm for behavior and fMRI before or after muscimol or aCSF infusion. (B) A stylized figure to represent an overview of the locations of the injury and muscimol drug injection sites, and the nomenclature used to describe the brain regions (ipsilesional = primary injured hemisphere; contralesional = less affected hemisphere opposite to the primary-injured hemisphere) and limb stimulations (muscimol-affected left limb and injury-affected right limb. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; Inj, injury; Mus, muscimol.

Brain injury and cannula placement

All study protocols were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA) Chancellor's Animal Research Committee and adhered to the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The method for induction of moderate CCI injury was performed as previously described.3,18,22–24 Briefly, rats (220–250 g in body weight) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane vaporized in O2 flowing at 0.8 L/min and placed on a homeostatic temperature-controlled blanket while being maintained in a stereotactic frame. CCI was produced using a 4-mm diameter impactor tip that was advanced through a 6-mm craniotomy (centered at 0 mm bregma and 3 mm left lateral to the sagittal suture) onto the brain using a 20-psi pressure pulse and to a deformation depth of 2 mm below the dural surface. Care was taken to prevent heat damage to the brain during drilling of the craniotomy by cooling the skull with sterile saline (0.9%).

Immediately following CCI injury, a permanent, in-dwelling plastic cannula (0.46 mm outer diameter, Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA) was placed into the contralesional homotopic primary sensory forelimb (S1-FL) cortex, an area that overlaps with the caudal forelimb cortex.25,26 Using stereotaxic coordinates from Paxinos and Watson's rat atlas data,27 a 0.8-mm burr hole was drilled in the skull above the S1-FL area using the following coordinates, and based on our previous functional MRI data7: +3.5 mm lateral, +0.5 mm rostral relative to bregma, and 2.5 mm below the outer skull surface. After carefully incising the dura with a 27-guage needle, the cannula was advanced into the center of the S1-Fl area and secured to the skull with cyanoacrylate gel glue and dental cement. The craniotomy was then sealed with a layer of non-bioreactive, Kwik-Cast silicon elastomer (Sarasota, FL) and the scalp was re-sutured and covered with a layer of bupivicaine local anesthetic solution and triple antibiotic ointment. Animals were placed in a recovery chamber with ambient temperature maintained at ∼28°C until they had awoken from anesthesia and then they were returned to their home cages. No mortalities occurred due to acute post-traumatic complications.

Cortical silencing

Immediately after surgery, injured animals were randomized (randomizer.org) into two groups: muscimol or aCSF. After behavioral testing on post-injury days 6 and 27, the following day (day 7 and 28), rats were re-anesthetized for 15 min with light sedation (isoflurane 1.5% in oxygen) and S1-FL cortex activity was temporarily silenced by infusion of 1 μL of the GABAA channel receptor agonist muscimol (1μg/μL in aCSF vehicle) through the cannula over a period of 10 min using a 5-μL syringe connected to an infusion pump (Stoelting, IL). This has previously been shown to inactivate a region 1–2 mm from the injection site.17 Vehicle-treated control rats received equivalent volume of aCSF (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) by the same injection procedure. The cannula was sealed with a dust cap (Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA). Following recovery from sedation, post-injection behavioral assessment was performed within 30 ± 10 min, well within the 2-h window during which muscimol levels remain in the region.17

Functional MRI

Forelimb-evoked fMRI was conducted at 5–6 weeks post-injury as described previously,7 before and within 1 h after muscimol or aCSF infusion (35 and 40 days post-injury, respectively) using a 7-Tesla Bruker Biospec spectrometer and a single channel receiver radiofrequencey coil actively decoupled from a whole body transmit coil (Fig. 1B). Briefly, blood-oxygen-level-dependent fMRI data were acquired under medetomidine sedation (0.05mg/kg intravenously followed by 0.1 mg/kg constant subcutaneous infusion) using a 1-shot echo-planar, gradient-recalled echo sequence (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE] = 2000/30 msec) using a 128 × 64 data matrix over a 3-cm2 field of view and 14 × 0.75-mm contiguous image slices. Data were acquired over three 40-sec periods of electrical stimulation of the left forelimb (3.5 mA, 10 Hz) interleaved with 60-sec rest periods. A two-dimensional rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) sequence was used to collect T2-weighted images with the following parameters: TR = 6018 msec, TE = 56 msec, RARE factor = 8, and using the same geometry as used for the fMRI protocol, except a data matrix of 128-read × 128-phase-encoding steps. Functional data were entered into the FEAT analysis pipeline,28,29 brain extracted, motion and slice-timing corrected, smoothed to 0.5 mm, registered to a template rat brain using the RARE data, and processed to determine statistical differences between pre-injection on post-injury day 35 and post-muscimol or aCSF data on post-injury day 40. Statistical maps were computed using a paired t test for muscimol pre/post-injection data that were cluster thresholded at z = 1.7 and p < 0.01 family-wise error corrected, whereas aCSF data were thresholded at z = 1.7 and p < 0.01 uncorrected given the low group size.

Assessment of forelimb function

Prior to injury, rats were habituated and trained in a staircase forelimb reaching/pellet retrieval apparatus21 (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN) for 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, until they reached 60% reaching success rate on both limbs, as with prior studies.24 We did not account for handedness among the rats and used all those that reached above 60% success, regardless of hand preference, by week 3, after which left cortex injury was immediately conducted. The number of steps cleared of sugar pellets within a 10-min period (pellet retrieved and eaten) is used as an objective measure of forelimb skilled-reaching ability. The number of pellets dropped is used as a measure of unskilled limb performance. Two trials were run for each rat per testing day and the results were averaged. Each trial was video-recorded for offline analysis. Reaching dexterity was assessed offline on a frame-by-frame basis. The reviewer was blinded to the treatment group and was asked to count the number of pellets eaten and dropped, and the total number of attempted reaches with each forelimb. An unsuccessful attempt was counted when a rat reached for a pellet inside a stairwell and then closed its digits in a grasping effort, but ultimately failed to hold and eat the pellet. The number of pellets eaten divided by the total attempts was used as a measure of reaching accuracy. The number of pellets dropped divided by the total number of reaching attempts was used as a measure of reaching inaccuracy. We consider that these normalized values provide a more precise measure of dexterity and sensory function compared with the pellets eaten and dropped, because it accounts for how much difficulty the rat had in aiming for and grasping each pellet.

Histology

At 40 days post-injury all rats were terminally anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100mg/kg intraperitoneally [IP]) and then transcardially perfused-fixed with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were post-fixed overnight, cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in PBS for ∼24 h at 4°C, sectioned at 50 μm, collected onto gelatinized microscope slides, stained with thionin, cleared in Citrisolv (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), and cover-slipped using Cytoseal 60 (Richard Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Eight mounted sections, 650 μm apart, were used to measure contusion volume by determining the left-right hemispheric difference in tissue volume using Stereoinvestigator software (Microbrightfield, Inc., Williston, VT). At this time post-injury, gross tissue atrophy and resolution of edema has already occurred, making the requirement for boundary criteria with which to judge the edge of the tissue far easier than at earlier times post-injury. As a result, the absolute tissue edge of all remaining tissue was used to delineate total hemispheric cortical gray + white matter, where white matter was the corpus callosum and external capsule. The difference between the hemispheric cortical areas was used as a measure of contusion area/section, which was multiplied by the intersection distance to obtain an estimate of contusion volume.

Statistical analysis

Group data were tested for equal variances and departure from normality using Levene's test for homogeneity and the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, respectively (R version 3.3.1, car and stats packages, respectively). The majority of the data were non-normality distributed and so the penalized quasi-likeihood method30 was implemented to model the data, which were transformed to best fit a log-normal distribution, and using generalized linear mixed modeling for testing of statistical inference (R functionglmmPQL from the MASS package).31 This method is a flexible technique that can deal with non-normal data, unbalanced designs, and crossed, random effects. An additive model was shown to be optimal using the Akaike information criterion, with group, time, and group × time assigned as fixed effects, and rat as a random effect. Acute (pre-injury to 7 days post-injury) and chronic injections (28–35 days post-injury) were considered as independent processes given the return of limb function to pre-injection levels in the time elapsed after the first injection to the second, and so were tested separately. Post hoc testing was calculated using the LSMEANS package32 with adjustment for multiple comparisons using Tukey's method. Adjusted probability (p) values are cited in the text along with the corresponding t statistic and degrees of freedom. Correlation analysis and calculation of the coefficient of determination (R2) were implemented using GraphPad version 7.04 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) on raw, untransformed data.

Results

We operationally define the hemisphere opposite the left, primary injured hemisphere as contralesional, and the injured hemisphere as ipsilesional (Fig. 1B). This is done in preference to using contralateral and ipsilateral, which do not accurately reflect the intended regional focus of the text when describing left versus right limb function in response to injury and subsequent right hemisphere-specific brain inactivation. In regard to limb nomenclature, we refer to the left limb, the intended target for muscimol arising from injection into the right, contralesional cortex, as the muscimol-affected limb. We refer to the right limb that is predominantly affected by the left, unilateral injury as the injury-affected limb.

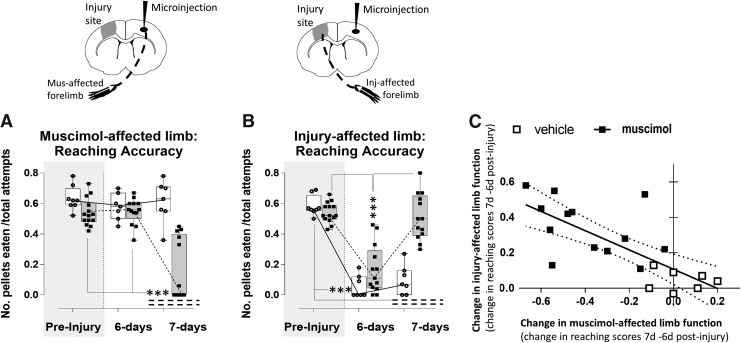

Contralesional cortical silencing normalizes injury-affected limb function at 1 week post-injury

Following forelimb reach training on the staircase task there was no between group difference in reaching accuracy (number of pellets eaten normalized to number of attempts) for either limb prior to induction of injury (t(20), left limb = 1.68, p > 0.05; t(20), right limb = 0.82, p > 0.05; Fig. 2A,B), indicating that the training was equivalent between the muscimol and the aCSF-treated groups (n = 13, 8, respectively). At 6 days after left CCI injury there was a significant reduction in reaching accuracy for the affected (right) forelimb in both muscimol and vehicle-injected, injured rats compared with the corresponding pre-injury data (t(36), pre-vehicle injection = 8.82, p < 0.001; t(36), pre-muscimol injection = 8.64, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B) but no effect on the left limb, which remained unaffected by injury (t(36), pre-vehicle injection = 0.85, p > 0.05; t(36), pre-muscimol injection = 0.14, p > 0.05; Fig. 2A). Importantly, there was no significant difference between the treatment groups for the effect of injury on limb reaching accuracy at 6 days (t(20) = −0.1, p > 0.05), indicating the impact of injury was similar for both groups. When the same injured rats were tested a day later at 7 days, shortly following either muscimol or vehicle (aCSF) injection into the contralesional (right) forelimb cortex, as expected there was a significant reduction in reaching accuracy from the corresponding left, muscimol-affected limb compared with the prior 6-day time-point (t(36) = 7.66, p < 0.001) and with pre-injury (t(36) = 7.62, p < 0.001), but not in injured rats that received vehicle injection, which remained unaffected and similar to pre-injury (t(36) = 0.36, p > 0.05; Fig. 2A). This reduction in function of the muscimol-affected forelimb indicates that successful silencing of the controlling contralesional cortex was achieved. This effect was accompanied by a concomitant normalization of the right, injury-affected limb at 7 days post-injury versus 6 days (t(36) = −7.93, p < 0.001), so that it was not different from pre-injury (t(36) = 0.66, p > 0.05); but crucially this occurred only in injured rats receiving muscimol, because reaching accuracy in vehicle-injected, injured rats remained significantly reduced from pre-injury values (t(36 = −8.21, p < 0.001), as well as from the muscimol-injected group at 7 day (t(20) = −7.24, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). Despite this overall significant effect, there was a variable effect of silencing as indicated by a large within-group variation in left, muscimol-affected forelimb function in the muscimol group at 7 days (Fig. 2A). However, using this variation we were able to show that there was an association between the degree of silencing and the degree to which the injury-affected limb becomes normalized. We tested for an association between the effect of muscimol and vehicle (the difference between left limb reaching between 6 and 7 days) upon the opposite, injury-affected limb (the difference between right limb reaching between 6 and 7 days) and found a significant correlation (R2 = 0.56, p = 0.002, Fig. 2C). In other words, the improvement in right, injury-affected forelimb function was linked to the degree of functional impairment imposed on the left limb through cortical silencing of the contralesional cortex.

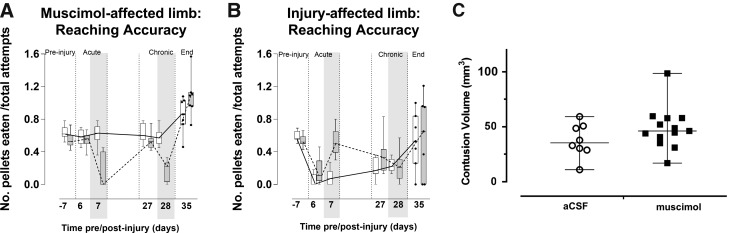

FIG. 2.

Acute time-point silencing normalizes injury-affected limb reaching accuracy. Reaching accuracy of the muscimol affected limb (A) and the injury-affected limb (B) was assessed by the number of pellets eaten normalized by the total number of attempts. (A) Contralesional silencing with muscimol (shaded bars) on day 7 post-injury significantly reduced reaching accuracy of the opposite, muscimol-affected forelimb compared with pre-injury and with pre-injection day 6 (p < 0.001), and compared with vehicle-injected, injured rats (open bars) at day 7 post-injury (p < 0.001), which remained unaffected. (B) Reaching accuracy of the injury-affected limb of both groups was significantly reduced at day 6 post-injury compared with pre-injury (p < 0.001). Muscimol injection on day 7 resulted in a significant increase in reaching accuracy compared with day 6 and compared with vehicle-injected (p < 0.001). Crucially, reaching accuracy of vehicle injected, injured rats remained significantly decreased from pre-injury at 7 days (p < 0.001) and not significantly different from 6 days. (C) Correlation plot of the effect of silencing on the muscimol-affected (left) limb (X axis, difference in 7–6 days reaching accuracy score) versus the improvement in the injury-affected (right) limb (Y axis, difference in 7–6 day reaching accuracy scores) in muscimol and vehicle-injected injured rats (closed vs. open squares, respectively, R = 0.56, p = 0.002). ***p < 0.001.

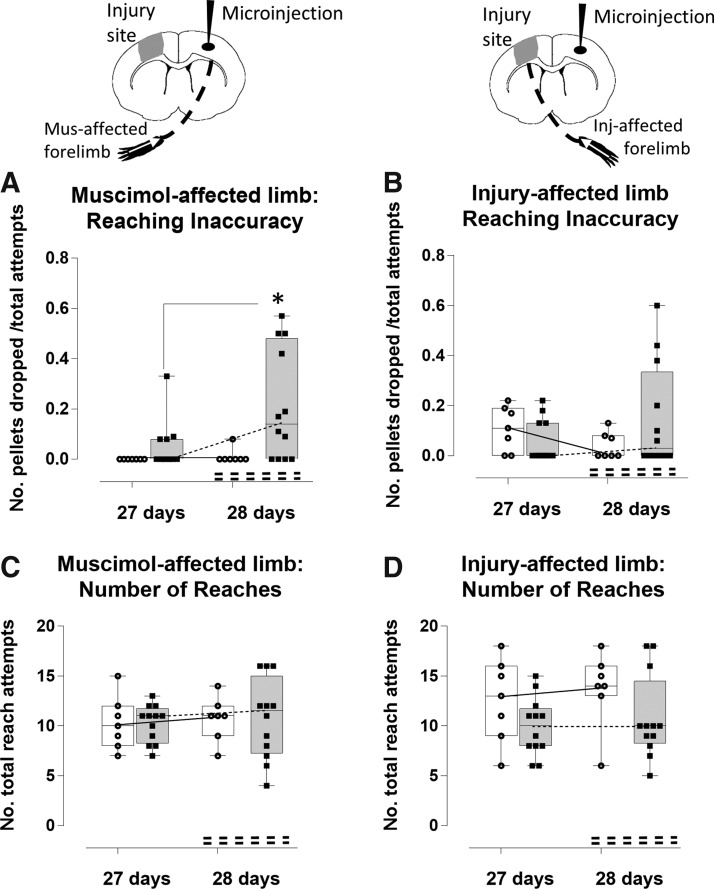

We also determined the effects of injury and silencing on reaching inaccuracy, as indicated by the number of the pellets dropped, normalized to the number of attempts (Fig. 3A,B). The effect was much less marked compared with reaching accuracy, with higher within-group variability. Despite this, we did find a detrimental effect of injury upon reaching inaccuracy of the right, injury-affected limb, but this was only significant at 6 days after injury in the muscimol-injected group compared with pre-injury when it was increased (t(36) = −3.0, p < 0.05, Fig. 3B), but not in the vehicle-injected group (t(36) = −1.90, p > 0.05). However, as expected, muscimol injection at 7 days post-injury reduced reaching inaccuracy of the muscimol-affected left limb as measured by the increased number of pellets dropped compared with 6 days post-injury (t(36) = −3.03, p < 0.05), whereas crucially there was no effect of vehicle (t(36) = 0.75, p > 0.05; Fig. 3A). This occurred with a concomitant trend toward improvement in the reach inaccuracy score of the right, injury-affected limb for the muscimol-injected group at 7 days compared with 6 days, although again this was outside significance (t(36) = 2.46; p = 0.16, Fig. 3B), whereas reach inaccuracy scores for vehicle-injected, injured rats remained unaffected from 6 days (t(36) = −0.15, p > 0.05). We found no association between the trend toward increased reaching inaccuracy in the muscimol-affected left limb and any reduction in reaching inaccuracy on the injury-affected right limb (R2 = 0.002, p > 0.05; data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Acute time-point silencing reduces injury-affected limb reaching inaccuracy. Reaching inaccuracy of the muscimol-affected limb (A) and the injury-affected limb (B) was assessed by the number of pellets dropped, and normalized by the total number of attempts in muscimol-injected (shaded bars) versus vehicle-injected, injured rats (open bars). The total number of attempts is plotted separately for the muscimol-affected (C) and the injury-affected limb (D). Silencing (A) significantly increased inaccuracy for reaching of the muscimol-affected limb at 7 compared with 6 days post-injury (p < 0.05), and (B) this also resulted in a trend toward fewer dropped pellets/attempt by the injury-affected limb at 7 compared with 6 days (not significant, p = 0.16), whereas the limb of the vehicle-injected, injured rats remained unaffected between day 6 and 7. (C) The number of reach attempts of the muscimol-affected limb did not vary significantly due to injury and either vehicle or muscimol injection, although it was more variable after muscimol-injection rats at 7 days. (D) The number of reach attempts of the injury-affected limb increased due to injury alone in both groups at 6 days compared with pre-injury (p < 0.05), and silencing significantly reduced this at 7 day (p < 0.001), whereaas vehicle injection had no effect.*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Inj, injury; Mus, muscimol.

We quantified the total number of reach attempts to normalize the number of pellets eaten and dropped to more precisely report on the degree of difficulty that the rat experienced in reaching for, and grasping the pellet. We found that there was no effect of injury or cortical injection on the number of reach attempts of the left, muscimol-affected limb, although it was highly variable after muscimol injection (t(36) = range 0–0.12, p > 0.05; Fig. 3C). However, the right injury-affected limb was used to make a significantly greater number of reach attempts in both injured groups at 6 days post-injury compared with pre-injury (t(36) = vehicle −3.09, p < 0.05; t(36) = muscimol −3.56, p < 0.01), indicating increased difficulty to achieve a successful reach due to injury (Fig. 3D). Although the effect of silencing on the muscimol-affected, left limb function at 7 days post-injury was variable for the number of reach attempts (Fig. 3C), it did have an overall significant, concomitant effect on the opposite, injury-affected limb at 7 days through a reduction in the total number of reach attempts compared with 6 days (t(36) = 5.50, p < 0.001, Fig. 3D). This effect was supported by a regression analysis that showed that among those rats that responded to muscimol by requiring greater number of reach attempts for success of the muscimol affected limb (6 of 13 rats), the number of attempts made by the opposite, injury-affected limb was correspondingly reduced, although this did not quite reach significance (R2 = 0.61, p = 0.068, data not shown).There was no effect of vehicle injection in the vehicle-injected, injured group at 7 days, which was similar to 6 days (t(36) = 1.90, p > 0.05).

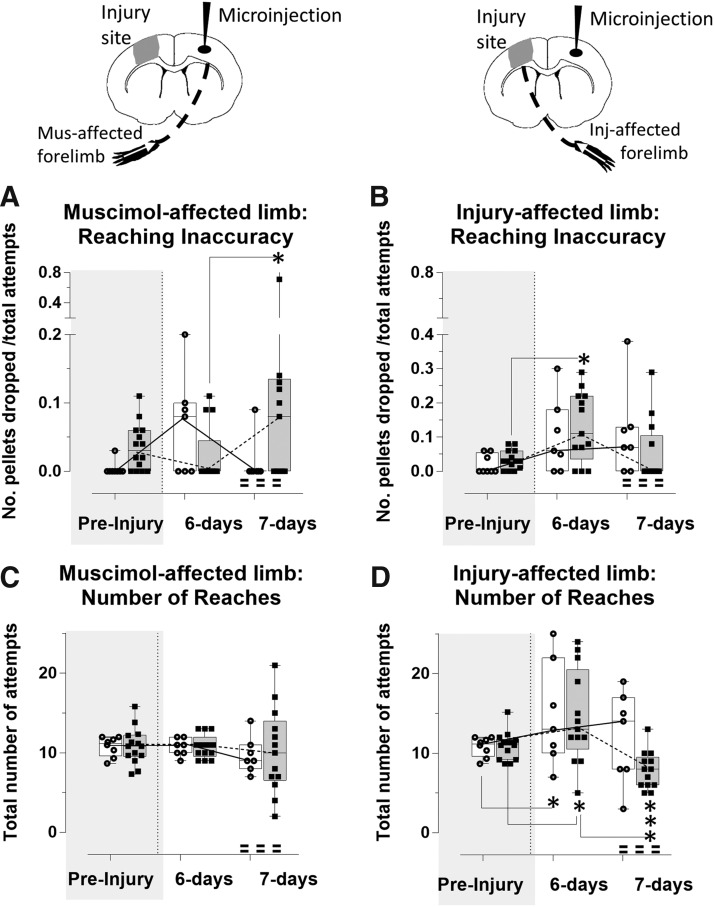

Cortical silencing worsens limb function at 4 weeks post-injury

One rat in each group was not tested at 4 weeks due to a damaged headset and cannula, reducing the group sizes to 12 and 7, muscimol and aCSF groups, respectively. To determine whether the improvement in skilled reaching elicited by muscimol silencing of the contralesional hemisphere extended to more chronic post-injury time-points, we retested the same rats at 4 weeks post-injury before and after a second injection of muscimol. Importantly, we found that the benefits of muscimol on left limb function at 7 days was transient, and did not persist at the chronic time-points, as indicated by the similarity of data points for reaching accuracy (Fig. 2A vs. Fig. 4A) and inaccuracy (Fig. 2B vs. 4B) for the pre-muscimol injection data at 27 days post-injury and the pre-muscimol injection data at 6 days post-injury. Contralesional cortex injection of muscimol 1 day later at 28 days post-injury once again had the expected effect on the left, injury-unaffected limb by significantly reducing the number of pellets eaten compared with 27 days (t(28) = 7.54, p < 0.001; Fig. 4A). Similarly, there was once again no effect of vehicle injection on reaching accuracy of the left limb at this time (t(28) = 0.87, p > 0.05). However, unlike the beneficial effect of silencing on reaching accuracy of the injury-affected, right limb at the earlier time-point (Fig. 2B), chronic time-point silencing had an unexpectedly variable effect, from an improvement in reaching accuracy in very few rats (3 of 12), to a worsening effect in all others, so that overall it was not significantly different from pre-injection (t(28) = 2.49, p = 0.16; Fig. 4B). Vehicle injection had no effect (t(28) = −0.48, p > 0.05). However, once again, taking advantage of the variable effect of muscimol injection on limb function, we tested for an association between the effect of silencing on reaching accuracy of the muscimol-targeted limb to assess any correlation to the effect of reaching on the injury-affected limb. We found there was a significant correlation, but unlike at the acute time-point, the greater the effect of silencing targeted to the muscimol-affected left limb (X axis, Fig. 4C), the greater the effect in worsening,rather than improving the reach accuracy scores of the injury-affected right limb (Y axis, Fig. 4C; R2 = 0.37, p = 0.006).

FIG. 4.

Chronic time-point silencing worsens injury-affected limb reaching accuracy. Reaching accuracy was assessed before (27 days post-injury) and during (28 days post-injury) a subsequent cortical silencing intervention for (A) the muscimo-affected limb and (B) injury-affected limb. (A) Silencing (shaded bars) significantly reduced reaching accuracy at 28 days compared with 27 days post-injury (p < 0.001), whereas it remained similar in vehicle-injected-injured rats (open bars). (B) Silencing resulted in a trend toward reduced number of pellets eaten via the injury-affected limb at 28 days compared with 27 days (p = 0.08), whereas it remained similar in vehicle-injected, injured rats. (C) Linear regression plot of the effect of silencing on the muscimol-affected (left) limb (X axis: difference in 28–27 days reaching accuracy score) versus the improvement in the injury-affected (right) limb (Y axis: difference in 28–27 days reaching accuracy scores) in muscimol and vehicle-injected injured rats (closed vs. open squares, respectively, R = 0.37, p = 0.006). ***p < 0.001. Inj, injury; Mus, muscimol.

These same effects of worsening affected limb function at the chronic post-injury time-point were also found for reaching inaccuracy, although similar to the acute time-point data, the effects were more variable. Silencing at 28 days increased reaching inaccuracy of the muscimol-targeted left limb compared with 27 days as expected (t(28) = −3.55, p < 0.01), with no effect of vehicle (t(28) = −0.20, p > 0.05; Fig. 6A). Whereas the corresponding effect of silencing on the injury-affected limb was also to increase reaching inaccuracy compared with 27 days, this did not reach significance (t(28) = −1.86, p > 0.05; Fig. 5B). The number of reach attempts was also not different between groups for either limb (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 6.

Temporary silencing has no significant, lasting effect on limb reaching and injury severity. Data from prior figures are re-plotted as entire time-course (pre-injury, acute, and chronic injection periods), for comparison with end-point 40-day data (n = 7/group). Reaching accuracy of (A) the muscimol-affected and (B) injury-affected limb in injured and vehicle-injected (open bars) versus injured muscimol-injected rats (shaded bars) was assessed by the number of pellets eaten/number of attempts and was not significantly different at 35 days post-injury for either limb between groups and compared to pre-injury values. (C) There was no difference in contusion volume between the two groups when assessed by histology at 40 days post-injury. Shaded area denotes time of muscimol or vehicle injection. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

FIG. 5.

Chronic time-point silencing has no effect on injury-affected limb reaching inaccuracy. Reaching inaccuracy of the muscimol-affected limb (A) and the injury-affected limb (B) was assessed by the number of pellets dropped, and normalized by the total number of attempts in muscimol-injected (shaded bars) versus injury-injected, injured rats (open bars). The total number of attempts is plotted separately for the muscimol-affected (C) and the injury-affected limb (D). Chronic time-point silencing (A) significantly reduced accuracy for reaching of the muscimol-affected limb at 28 compared with 27 days post-injury (p < 0.05), and (B) this also resulted in a trend toward more dropped pellets/attempt by the injury-affected limb at 28 compared with 27 days (not significant), whereas the limb of the vehicle-injected, injured rats remained unaffected. (C) The number of reach attempts of the muscimol-affected limb in injured rats did not vary significantly and was similar to vehicle injected, injured rats, although there was greater variability at 28 days. (D) The number of reach attempts of the injury-affected limb also remained unaffected by vehicle compared with muscimol treatment. *p < 0.05. Inj, injury; Mus, muscimol.

Finally, we also tested whether the degree of functional impairment due to silencing was different between the acute (7 days) and chronic time-point injections (28 days) of muscimol, and whether this might have confounded the analysis. For example, if the degree of silencing at the chronic time-point was lower compared with acute injection, perhaps due to the repeated injection, then this might explain the absence of any beneficial effects on the injury-affected forelimb function. However, we found that although acute time-point injections resulted in a fall in accuracy from a pre-injection value of 54% to 16% (percentage of pellets eaten), chronic time-point injections resulted in a similar reduction from a pre-injection accuracy of 53% to 18% after injection, indicating the injections were equally effective at impairing accuracy between the two time-points.

Temporary silencing has no long-term effects on forelimb function and injury severity

We determined whether repeated temporary silencing resulted in any long-term effects on function of either forelimb. We repeated the staircase reaching task at 5 weeks (35 days) after injury using a subset of the muscimol and vehicle-injected, injured rats (n = 7/group) and found that despite the earlier interventions that resulted in significant alterations in limb function, there was no significant effect of prior treatment (muscimol vs. vehicle) for either left (t(46) = 0.42, p > 0.05) or right limb at 5 weeks (t(46) = −0.17, p > 0.05; Fig. 5A,B). In other words, multiple injections of muscimol had no effect on spontaneous recovery of forelimb function. Tissue volume analysis of the brains showed that there was no significant group difference in contusion volume (Fig. 5C), also indicating that there was no long-term consequence of the temporary silencing (t(19) = 1.41, p > 0.05).

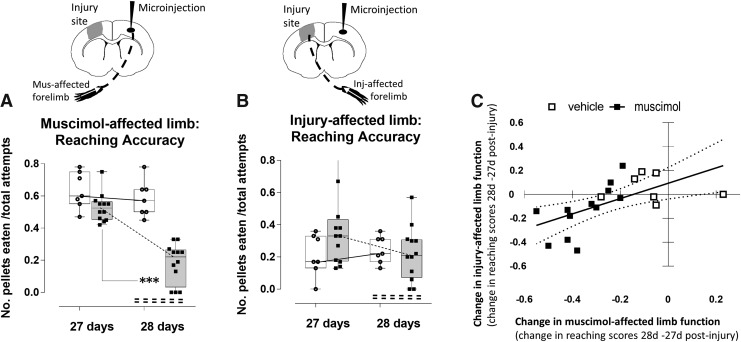

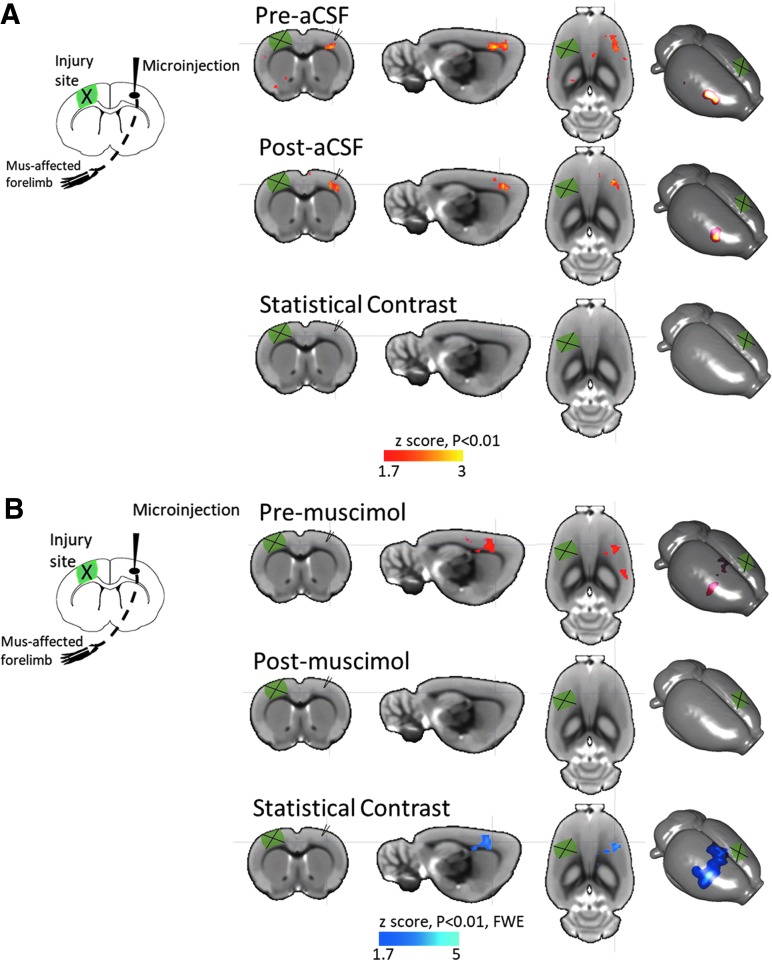

Functional imaging confirmation of cortical inactivation

Following behavioral testing, we confirmed that the method of cortical inactivation using muscimol worked in our laboratory in a subset of the rats (n = 11 muscimol, n = 3 aCSF) by acquiring left forelimb-evoked fMRI data in a separate cohort of injured rats before and after contralesional (right) injection of muscimol at 5–6 weeks post-injury, and compared it with injured rats before and after aCSF infusion at the same post-injury time-point. We found the expected cortical activation in the forelimb area of the contralesional cortex opposite the stimulated limb both before and after aCSF injection, with no statistical difference due to time (Fig. 7A). Although we found a similar contralesional brain activation in rats before muscimol infusion, the activation was not present the following day within 1 h of infusion, indicating a significant decrease in activity due to muscimol, and successful demonstration of the inactivation paradigm used herein (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Functional imaging confirmation of cortical inactivation. (A) Mean activation in right cortex evoked by electrical stimulation of the left forelimb is similar before (Pre-aCSF) and after (Post-aCSF) aCSF infusion into the contralesional cortex (red/yellow color), so that there was no statistical difference in activation. (B) Activation was similar to aCSF before muscimol infusion (Pre-muscimol, red/yellow color) but was not present after (Post-muscimol) indicating a significant decrease in activation due to cortical inactivation by muscimol (blue color). Statistical data are shown overlaid on a rat brain template showing coronal, sagittal, axial, and three-dimensional surface projection plots. aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid; FWE, family-wise error corrected.

Discussion

The traumatically injured brain is well known to be deficient in numerous functional and structural networks clinically,33 and increasingly so in experimental models.34,35 Altered brain function is of course a defining characteristic of the traumatically injured brain, and alterations within functional networks or between-circuit connectivity has been shown to be consistent with behavioral deficits associated not just with moderate or severe TBI,36–38 but increasingly so with milder injury39 or concussion.40 However, what remains less obvious is exactly which regions of brain are complicit in altered function, whether brain areas evolve functionally after injury to cause further alterations in function, and whether this is always toward recovery or further dysfunction that impedes progress. Although after moderate and severe injury functional deficits are primarily, but not always, attributable to damaged or lost brain tissue, the continued dysfunction of surviving, adjacent, injured tissue is a far less well understood and studied phenomenon. Neuroprotective strategies have been shown to prevent tissue loss in these brain areas,41–43 but these potentially salvageable regions such as the pericontusional area, or tissue adjacent to the injury epicenter are already at risk for development of seizure type activity,44,45 and the effect of interventions on this have not been addressed. Moreover, far less is known about connected brain regions remote from major sites of injury (i.e., diaschisis), and the effect that they might have on recovery mechanisms. We believe that this is important to understand if we are to make progress toward determining how best to treat dysfunction, and ultimately to help make advancements in understanding not only when current neurorehabilitative therapies might be optimally and safely applied post-injury, but also whether more thought should be given to how they target the brain regionally.

Acute post-injury plastic connections

In the current study we have shown that when transient inactivation of the homotopic brain region opposite the primary injury site is conducted acutely post-injury, the effect is to immediately normalize injury-affected limb function at a post-injury time when it would otherwise be dysfunctional. We would caution that whereas reaching ability was normalized with regard to the gross limb movements measured here, a detailed kinematic analysis of limb and paw movement may well have revealed remaining fine motor deficits, as indicated by others.46,47 However, prior data in this TBI model have shown the cortical map subserving affected forelimb function is almost wholly transferred to the less affected, contralesional cortex at this same acute time-point post-injury.7 Given that the impact of muscimol in the present study is focused on temporarily decimating this map in the contralesional cortex, as indicated by deficits in the muscimol-affected limb, then the immediate resumption of affected forelimb function must indicate two things: (1) that circuit reorganization from the ipsilesional to the contralesional cortex as a shifted cortical map is merely temporary at this time post-injury, or that it is at least incomplete and responsive to modulation to move to other brain regions, and (2) that the contralesional cortex exerts control over affected forelimb function in the untreated, spontaneously recovering rat at this acute post-injury time-point by preventing spontaneous resumption of reaching ability.

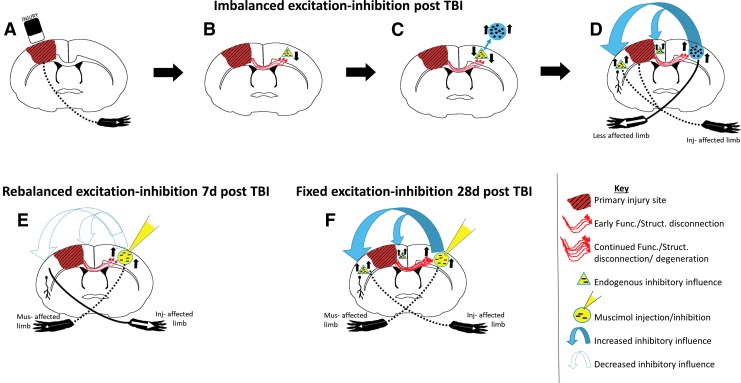

A cortical rebalancing hypothesis

One possible hypothesis to explain the resumption of reaching is a hemispheric imbalance in excitation and inhibition, as proposed by others after stroke48,49 (Fig. 8A–D), whereby when injury is limited mainly to one hemisphere, it lessens inhibitory output to the opposite, contralesional hemisphere through temporary functional and/or more permanent structural injury to the transcallosal fibers. This results in hyperexcitation of the less injured, contralesional hemisphere that can then exert greater control over ipsilesional function through increased inhibition. This is indeed an attractive notion, because a reduction in commissural fibers occurs in this CCI model,50,51 together with development of increased contralesional hemisphere hyperexcitability,7 alterations in functional connectivity,3 and an imbalance in the ipsilesional GABAergic and glutamate receptors.5,52–55 We did not remap brain activity after cortical inactivation in these studies, so it remains unknown whether or not the ipsilesional cortex resumed control over affected-limb function as we illustrate in a hypothetical model (Fig. 8E), or whether other remote brain areas assumed control. It will be important in future studies to assess this, especially after longer term periods of modulation.56

FIG. 8.

Hypothetical model of (A–D) imbalanced-excitation-inhibition after injury and the effect of (E) early versus (F) delayed intervention. (A) Injury (red/black stripped region) results in forelimb deficits in the injury affected forelimb (injury-affected forelimb; dotted line to opposite limb), and (B) also leads to trans-hemispheric functional and structural disconnection to remote, contralesional regions (red arrows) and a gradual reduction in inhibitory influence to the contralesional cortex (yellow triangles), so that (C) increased contralesional excitability develops over time post-injury (blue circle) as trans-hemispheric structural/axonal dieback occurs. (D) This in turn leads to a greater inhibitory influence on the ipsilesional hemisphere (blue arrows) preventing more ipsilesional cortex reorganization chronically after injury (yellow triangles). (E) Intervention with muscimol acutely after injury to inhibit contralesional cortex (yellow circle) and temporarily paralyzes the opposite, muscimol-affected limb (musimol-affected limb; dotted line to opposite limb) rebalances cross-brain inhibition (open, dotted arrows; absence of yellow triangles) and rescues injury-affected forelimb function (solid line to limb). (F) Muscimol infusion at a chronic post-injury time-point has either no effect or a worsening effect on forelimb function, possibly because further functional and structural disconnection has occurred (red arrows) so that remote/contralesional effects over ipsilesional reorganization remains fixed (blue arrows; presence of yellow triangles), preventing any ipsilesional reorganization. It might also indicate that control over affected limb function is driven by contralesional cortex in more severely injured rats. Func., functional; Inj, injury; Mus, muscimol; Struct., structural; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

This potential for spontaneous functional reorganization to remote regions and susceptibility to neuromodulation is consistent with the existence of the well-known idea of significant plastic potential early after injury. This is also supported by prior resting-state fMRI connectivity data in this model, which showed that increased local functional connectivity and whole brain network modularity, a parameter reflecting the degree of community type architectural arrangement of circuits in the brain, is reduced at 1 week after CCI injury but not thereafter.3 The blurring of circuit boundaries indicated by that data would suggest that early post-injury intervention via neuromodulation and/or neurorehabilitative training-induced “circuit shaping” is required to take full advantage of this brain state.

Reduced pliability of function at chronic post-injury times

Neuromodulation of contralesional cortex function at 4 weeks post-injury not only failed to improve affected forelimb function, but it negatively interfered with function in the majority of rats tested. We interpret this as indicating: (1) circuits partly or wholly controlling affected forelimb function reorganize more permanently to the contralesional homotopic cortex by 4 weeks and, (2) there is a critical period post-injury for temporary, enhanced plastic potential of cortical circuits involved in forelimb function that closes, or is at least less malleable at some point after 1 week post-injury in the rat.

One possibility to explain the reduced efficacy of delayed modulation of function is that following the initial structural and functional disconnection that occurs, further hemispheric disconnections continue after injury that eventually reach a threshold beyond which reorganization is less malleable, even after pharmacological intervention (Fig. 8F). In fact, continued neuronal cell death and white matter atrophy are well-known to occur for at least up to 1 year post-injury in the rat.57–59 Therefore, it is conceivable that following the initial wallerian degeneration of axon fibers that takes around 24 h,60 disconnections continue from acute to chronic time-points that further isolates the ipsilesional cortex and prevents further circuit modifications. In agreement with this, it is notable that the effects of axon degeneration and associated local changes in synaptic and dendritic processes is not completed for many weeks after transection of the corpus callosum or other white matter tracts in the brain.61 Finally, it is also just as likely that functional recovery of some axonal fibers occur, as shown at 7 days after fluid percussion brain injury in the rat,62 and that they then act to quell further cortical map changes in the gray matter. Further experimentation is necessary to determine causality here, and methods utilizing simultaneous quantification of structural and functional connectivity are required to do this using imaging and electrophysiological methods.

Whether or not the period for enhanced plasticity can be lengthened by prompt and sustained neuromodulation, or reopened chronically after injury, remains to be determined. Previous work after adult rat cortical lesioning has shown that the duration of pharmacological inactivation was highly correlated with the final level of recovery, suggesting that the duration of inhibition is important.63 What is clear from the current results is that they support the use of prompt neurorehabilitative intervention to regain sensorimotor control. It is noteworthy that this is somewhat contraindicated by data from the fluid percussion injury model showing that early exercise blunts the injury-induced rise in plasticity-associated proteins in hippocampus over the first week post-injury.64 This disparity would support a model of rehabilitation focused on training of specific brain circuits beginning at early time-points post-injury.

Although these data are specific to rodent models of injury rather than clinical cases where simple unilateral injury is relatively rare, the mechanisms underlying diaschisis and the local versus distant effects on brain function are very likely to be comparable to functional disconnections that occur within a hemisphere, that clinically might arise from either focal hematomas or diffuse axon injuries. This underlies the importance of obtaining both structural and functional imaging data in human subjects to assess not only the nature of the early post-injury structural-functional relationship, but to determine whether ongoing structural atrophy and disconnections act to further alter or limit the shaping of functional circuits.

In conclusion, we have shown that the contralesional cortex is causally involved in affected forelimb function after CCI injury in the rat, and that early but not delayed intervention to silence contralesional activity is successful in improving limb function. Ongoing functional and structural disconnection may occur to prevent further drug-induced modifications of post-injury circuits so that they are no longer responsive to neuromodulation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Andrew Frew and the UCLA In Vivo Imaging Center.

Funding was from the National Institutes of Health NINDS NS091222, the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center. The project described was also supported in part by the MRI Core of the Semel Institute of Neuroscience at UCLA, which is supported by Intellectual Development and Disabilities Research Center grant U54HD087101-01 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Kreber L.A., and Griesbach G.S. (2016). The interplay between neuropathology and activity based rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 1640, 152–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schallert T., Fleming S.M., and Woodlee M.T. (2003). Should the injured and intact hemispheres be treated differently during the early phases of physical restorative therapy in experimental stroke or parkinsonism? Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 14, S27–S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harris N.G.G., Verley D.R.R., Gutman B.A.A., Thompson P.M.M., Yeh H.J.J., and Brown J.A.A. (2016). Disconnection and hyper-connectivity underlie reorganization after TBI: a rodent functional connectomic analysis. Exp. Neurol. 277, 124–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holschneider D.P., Guo Y., Wang Z., Roch M., and Scremin O.U. (2013). Remote brain network changes after unilateral cortical impact injury and their modulation by acetylcholinesterase inhibition. J. Neurotrauma 30, 907–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le Prieult F., Thal S.C., Engelhard K., Imbrosci B., Mittmann T., Prieult F. Le, Thal S.C., Engelhard K., and Imbrosci B. (2016). Acute cortical transhemispheric diaschisis after unilateral traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 14, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris N.G., Chen S.F., and Pickard J.D. (2003). Reorganisation after experimental traumatic brain injury: a functional autoradiography study. J.Cerebral Metab. Blood Flow 21, 1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verley D.R., Torolira D., Pulido B., Gutman B., Bragin A., Mayer A., and Harris N.G. (2018). Remote changes in cortical excitability after experimental TBI and functional reorganization. J. Neurotrauma doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5536 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allred R.P., Cappellini C.H., and Jones T.A. (2010). The “good” limb makes the “bad” limb worse: experience-dependent interhemispheric disruption of functional outcome after cortical infarcts in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 124, 124–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim S.Y., Allred R.P., Adkins D.L., Tennant K.A., Donlan N.A., Kleim J.A., and Jones T.A. (2015). Experience with the “good” limb induces aberrant synaptic plasticity in the Perilesion cortex after stroke. J. Neurosci. 35, 8604–8610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chu C.J., and Jones T.A. (2000). Experience-dependent structural plasticity in cortex heterotopic to focal sensorimotor cortical damage. Exp. Neurol. 166, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones T.A., and Schallert T. (1992). Overgrowth and pruning of dendrites in adult rats recovering from neocortical damage. Brain Res. 581, 156–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luke L.M., Allred R.P., and Jones T.A. (2004). Unilateral ischemic sensorimotor cortical damage induces contralesional synaptogenesis and enhances skilled reaching with the ipsilateral forelimb in adult male rats. Synapse 54, 187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsu J.E., and Jones T.A. (2006). Contralesional neural plasticity and functional changes in the less-affected forelimb after large and small cortical infarcts in rats. Exp. Neurol. 201, 479–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones T.A., Liput D.J., Maresh E.L., Donlan N., Parikh T.J., Marlowe D., and Kozlowski D.A. (2012). Use-dependent dendritic regrowth is limited after unilateral controlled cortical impact to the forelimb sensorimotor cortex. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1455–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kozlowski D.A., Leasure J.L., and Schallert T. (2013). The control of movement following traumatic brain injury. Compr. Physiol. 3, 121–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wallace H., Glazewski S., Liming K., and Fox K. (2001). The role of cortical activity in experience-dependent potentiation and depression of sensory responses in rat barrel cortex. J. Neurosci. 21, 3881–3894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin J.H., and Ghez C. (1999). Pharmacological inactivation in the analysis of the central control of movement. J. Neurosci. Methods 86, 145–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris N.G.G., Verley D.R.R., Gutman B.A.A., and Sutton R.L.L. (2016). Bi-directional changes in fractional anisotropy after experiment TBI: disorganization and reorganization? Neuroimage 133, 129–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wallen M.A., Mackay S., Duff S.M., McCartney L.C., and O'flaherty S.J. (2001). Upper-limb function in Australian children with traumatic brain injury: a controlled, prospective study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 82, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walker W.C., and Pickett T.C. (2007). Motor impairment after severe traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal multicenter study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 44, 975–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Montoya C.P., Campbell-Hope L.J., Pemberton K.D., and Dunnett S.B. (1991). The “staircase test”: a measure of independent forelimb reaching and grasping abilities in rats. J. Neurosci. Methods 36, 219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harris N.G., Chen S.-F., and Pickard J.D. (2013). Cortical reorganisation after experimental traumatic brain injury: a functional autoradiography study. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1137–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris N.G., Nogueira M.S.M., Verley D.R., and Sutton R.L. (2013). Chondroitinase enhances cortical map plasticity and increases functionally active sprouting axons after brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 30, 1257–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris N.G.N.G., Mironova Y.A.Y.A., Hovda D.A.D.A., and Sutton R.L.R.L. (2010). Chondroitinase ABC enhances pericontusion axonal sprouting but does not confer robust improvements in behavioral recovery. J. Neurotrauma 27, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mansoori B.K., Jean-Charles L., Touvykine B., Liu A., Quessy S., and Dancause N. (2014). Acute inactivation of the contralesional hemisphere for longer durations improves recovery after cortical injury. Exp. Neurol. 254, 18–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Combs H.L., Jones T.A., Kozlowski D.A., and Adkins D.L. (2016). Combinatorial motor training results in functional reorganization of remaining motor cortex after controlled cortical impact in rats. J. Neurotrauma 33, 741–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paxinos G., and Watson C. (1998). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Woolrich M. (2008). Robust group analysis using outlier inference. Neuroimage 41, 286–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith S.M., Jenkinson M., Woolrich M.W., Beckmann C.F., Behrens T.E.J.J., Johansen-Berg H., Bannister P.R., De Luca M., Drobnjak I., Flitney D.E., Niazy R.K., Saunders J., Vickers J., Zhang Y., De Stefano N., Brady J.M., and Matthews P.M. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, Suppl, 1, S208–S219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolfinger R., and O'connell M. (1993). Generalized linear mixed models a pseudo-likelihood approach. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 48, 233–243 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Venables W.N., and Ripley B.D. (2002). Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed. Springer U.S.: New York [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lenth R.V. (2016). Least-Squares Means: The R Package Ismeans. J. Stat. Softw. 69, 1–33 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharp D.J., Scott G., and Leech R. (2014). Network dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 10, 156–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holschneider D.P., Guo Y., Wang Z., Roch M., and Scremin O.U. (2013). Remote brain network changes after unilateral cortical impact injury and their modulation by acetylcholinesterase inhibition. J. Neurotrauma 30, 907–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mishra A.M., Bai X., Sanganahalli B.G., Waxman S.G., Shatillo O., Grohn O., Hyder F., Pitkänen A., and Blumenfeld H. (2014). Decreased resting functional connectivity after traumatic brain injury in the rat. PLoS One 9, e95280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayer A.R., Mannell M.V, Ling J., Gasparovic C., and Yeo R.A. (2011). Functional connectivity in mild traumatic brain injury. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 1825–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stevens M.C., Lovejoy D., Kim J., Oakes H., Kureshi I., and Witt S.T. (2012). Multiple resting state network functional connectivity abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 293–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jilka S.R., Scott G., Ham T., Pickering A., Bonnelle V., Braga R.M., Leech R., and Sharp D.J. (2014). Damage to the salience network and interactions with the default mode network. J. Neurosci. 34, 10798–10807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayer A.R., Ling J.M., Allen E.A., Klimaj S.D., Yeo R.A., and Hanlon F.M. (2015). Static and dynamic intrinsic connectivity following mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 32, 1046–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnson B., Zhang K., Gay M., Horovitz S., Hallett M., Sebastianelli W., and Slobounov S. (2012). Alteration of brain default network in subacute phase of injury in concussed individuals: resting-state fMRI study. Neuroimage 59, 511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cebak J.E., Singh I.N., Hill R.L., Wang J.A., and Hall E.D. (2017). Phenelzine protects brain mitochondrial function in vitro and in vivo following traumatic brain injury by scavenging the reactive carbonyls 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein leading to cortical histological neuroprotection. J. Neurotrauma 34, 1302–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pandya J.D., Pauly J.R., Nukala V.N., Sebastian A.H., Day K.M., Korde A.S., Maragos W.F., Hall E.D., and Sullivan P.G. (2007). Post-injury administration of mitochondrial uncouplers increases tissue sparing and improves behavioral outcome following traumatic brain injury in rodents. J. Neurotrauma 24, 798–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moro N., Ghavim S.S., Harris N.G., Hovda D.A., and Sutton R.L. (2016). Pyruvate treatment attenuates cerebral metabolic depression and neuronal loss after experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 1642, 270–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reid A.Y., Bragin A., Giza C.C., Staba R.J., and Engel J. (2016). The progression of electrophysiologic abnormalities during epileptogenesis after experimental traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia 57, 1558–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bragin A., Li L., Almajano J., Alvarado-Rojas C., Reid A.Y., Staba R.J., and Engel J. (2016). Pathologic electrographic changes after experimental traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia 57, 735–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whishaw I.Q., Pellis S.M., Gorny B., Kolb B., and Tetzlaff W. (1993). Proximal and distal impairments in rat forelimb use in reaching follow unilateral pyramidal tract lesions. Behav. Brain Res. 56, 59–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kleim J.A., Boychuk J.A., and Adkins D.L. (2007). Rat models of upper extremity impairment in stroke. ILAR J. 48, 374–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Johansen-Berg H., Dawes H., Guy C., Smith S.M., Wade D.T., and Matthews P.M. (2002). Correlation between motor improvements and altered fMRI activity after rehabilitative therapy. Brain 125, 2731–2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Di Lazzaro V., Dileone M., Capone F., Pellegrino G., Ranieri F., Musumeci G., Florio L., Di Pino G., and Fregni F. (2014). Immediate and late modulation of interhemipheric imbalance with bilateral transcranial direct current stimulation in acute stroke. Brain Stimul. 7, 841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Harris N.G., Verley D.R., Gutman B.A., and Sutton R.L. (2016). Bi-directional changes in fractional anisotropy after experiment TBI: disorganization and reorganization? Neuroimage 133, 129–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soblosky J.S., Matthews M.A., Davidson J.F., Tabor S.L., and Carey M.E. (1996). Traumatic brain injury of the forelimb and hindlimb sensorimotor areas in the rat: physiological, histological and behavioral correlates. Behav. Brain Res. 79, 79–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee S., Ueno M., and Yamashita T. (2011). Axonal remodeling for motor recovery after traumatic brain injury requires downregulation of γ-aminobutyric acid signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2, e133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Raible D.J., Frey L.C., Cruz Del Angel Y., Russek S.J., and Brooks-Kayal A.R. (2012). GABA(A) receptor regulation after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 29, 2548–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cantu D., Walker K., Andresen L., Taylor-Weiner A., Hampton D., Tesco G., and Dulla C.G. (2015). Traumatic brain injury increases cortical glutamate network activity by compromising GABAergic control. Cereb. Cortex 25, 2306–2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Drexel M., Puhakka N., Kirchmair E., Hörtnagl H., Pitkänen A., and Sperk G. (2015). Expression of GABA receptor subunits in the hippocampus and thalamus after experimental traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology 88, 122–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li L., Rema V., and Ebner F.F. (2005). Chronic suppression of activity in barrel field cortex downregulates sensory responses in contralateral barrel field cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 3342–3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bramlett H.M., and Dietrich W.D. (2002). Quantitative structural changes in white and gray matter 1 year following traumatic brain injury in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 103, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Smith D.H., Chen X.H., Pierce J.E.S., Wolf J.A., Trojanowski J.Q., Graham D.I., and Mcintosh T.K. (1997). Progressive atrophy and neuron death for one year following brain trauma in the rat. J. Neurotrauma 14, 715–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pischiutta F., Micotti E., Hay J.R., Marongiu I., Sammali E., Tolomeo D., Vegliante G., Stocchetti N., Forloni G., De Simoni M.G., Stewart W., and Zanier E.R. (2018). Single severe traumatic brain injury produces progressive pathology with ongoing contralateral white matter damage one year after injury. Exp. Neurol. 300, 167–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Coleman M. (2005). Axon degeneration mechanisms: commonality amid diversity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 889–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Payne B.R., Pearson H.E., and Berman N. (1984). Deafferentation and axotomy of neurons in cat striate cortex: time course of changes in binocularity following corpus callosum transection. Brain Res. 307, 201–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reeves T.M., Phillips L.L., and Povlishock J.T. (2005). Myelinated and unmyelinated axons of the corpus callosum differ in vulnerability and functional recovery following traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 196, 126–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mansoori B.K., Jean-Charles L., Touvykine B., Liu A., Quessy S., and Dancause N. (2014). Acute inactivation of the contralesional hemisphere for longer durations improves recovery after cortical injury. Exp. Neurol. 254, 18–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Griesbach G.S., Gomez-Pinilla F., and Hovda D.A. (2004). The upregulation of plasticity-related proteins following TBI is disrupted with acute voluntary exercise. Brain Res. 1016, 154–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]