Abstract

Objectives

This meta-analysis aimed to demonstrate the impact of preoperative exercise therapy on surgical outcomes in patients with lung cancer and COPD. Pulmonary function and muscle capacity were investigated to explore their potential links with outcome improvements after exercise.

Methods

Articles were searched from PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library with criteria of lung cancer patients with or without COPD, undergoing resection, and receiving preoperative exercise training. Key outcomes were analyzed using meta-analysis.

Results

Seven studies containing 404 participants were included. Patients receiving preoperative exercise training had a lower incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs; OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.27–0.71) and shorter length of hospital stay (standardized mean difference −4.23 days, 95% CI −6.14 to −2.32 days). Exceptionally, pneumonia incidence remained unchanged. Patients with COPD could not obviously benefit from exercise training to reduce PPCs (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.18–1.08), but still might achieve faster recovery. No significant difference in pulmonary function was observed between the two groups. However, 6MWD and VO2 peak were significantly improved after exercise training.

Conclusion

Preoperative exercise training may reduce PPCs for lung cancer patients. However, for patients with COPD undergoing lung cancer resection, the role of exercise is uncertain, due to limited data, which calls for more prospective trials on this topic. Rehabilitation exercise strengthens muscle capacity, but does not improve impaired pulmonary function, which emphasizes the possible mechanism of the protocol design.

Keywords: preoperative exercise, lung cancer, COPD, postoperative pulmonary complications, 6MWD, VO2 peak

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most fatal cancer worldwide, with an estimated 1.2 million new cases and 1.1 million deaths in 2012.1 Lung cancer is also the leading cause of cancer death in low-urbanization areas for both males and females. The number of deaths from lung cancer in low-urbanization areas was 35,100, with mortality of 40.71 in 100,000.2 Surgical resection remains the key treatment for patients with lung cancer. However, many patients referred for surgery may also have comorbidities, such as COPD or other systematic diseases,3 which increase the risks of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Modern programs for enhanced recovery after surgery often include preoperative exercise training to reduce postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs). Although isolated studies have looked at the impact of such preoperative exercise on patients with lung cancer and COPD, a comprehensive meta-analysis of the available data has hitherto been lacking. Some studies have revealed that intense-exercise therapy delivered in the perioperative period might be effective in helping patients recover well after lung surgery,4,5 though the extent of improvement varied among these reports. At the same time, there have been other studies not showing positive effects after rehabilitation training.6–8

PPCs are common after abdominal, cardiac, or thoracic surgery, and are associated with a higher rate of mortality, higher hospital costs, and prolonged hospital length of stay (LOS).5 Two systemic reviews have reported that intense exercise before lung surgery might be applied as an effective preoperative therapy to decrease the risk of PCs.4,5,9,10 Nevertheless, neither of the reviews conducted a meta-analysis, because of the substantial heterogeneity among the intervention methods. Although statistical analysis was lacking, the outcomes described after exercise were clearly supportive of further meta-analysis. A recently published meta-analysis11 presented optimistic evidence of the impact of preoperative exercise training on surgical outcomes. However, the unselected targeting population and limited sample size indicated that more trials were needed to distinguish the potential benefit.

For the large group of patients with lung cancer and COPD at diagnosis, the role of preoperative exercise in this specific group requires further investigation. Several randomized studies that included patients with COPD for preoperative rehabilitation were published recently, which may add more evidence in this regard. More importantly, detailed exploration of outcome improvement could facilitate protocol design for exercise therapy, such as pulmonary function rehabilitation or muscle-strengthening training. Therefore, we designed this meta-analysis with the aim of determining whether preoperative exercise helps to improve surgical outcomes in patients with lung cancer and COPD. Parameters of pulmonary function and muscle capacity were investigated to explore their potential links with outcome improvements after exercise training.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and presented based on PRISMA guidance.12 The meta-analyses of randomized trials adhered to the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement. The protocol for this meta-analysis is available from PROSPERO (CRD42018088413).

Eligibility criteria

We only included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective trials of preoperative exercise training compared with no exercise training for lung cancer patients with or without COPD. We considered studies published in any language. Patients with usual care were set as the control group. After these preoperative interventions and basic therapy, patients received video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open thoracotomy, as scheduled. Types of surgery included wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy, and pneumonectomy. Patients received similar clinical monitoring after surgery, and PCs were clearly recorded. A subset of patients in the included trials was diagnosed with mild or moderate COPD, whose data were extracted for further analysis.

Interventions

Protocols of the included studies varied in terms of exercise type, frequency, and intensity, ranging from three times per day for 1 week13 to five times per week for 4 weeks.14 Furthermore, two types of investigation after exercise were involved in the included studies: muscle capacity and pulmonary function analysis. Exercise programs contained aerobic exercise, resistance training, inspiratory muscle training, and education. In some studies, patients were advised to undertake a warm-up before exercise (after a 5-minute warm-up period, 50% of peak work rate was achieved).15

Outcome measurements

Primary outcomes were PPCs (summarized by type based on included studies: pneumonia, atelectasis, pulmonary embolism, respiratory failure, dyspnea, hemorrhagic drainage, empyema, interstitial pneumonia, bronchial stump dehiscence, bronchospasm, and bronchopleural fistula), pneumonia after surgery (new infiltrate plus either fever [>38°C] and white-blood-cell count >11,000 or fever and purulent secretions),11 duration of chest tube, and postoperative LOS. Secondary outcomes focused on the patients with lung cancer and COPD, including PPCs and postoperative LOS. Postintervention pulmonary function enhancement was also compared to analyze possible reasons linked with outcome change after preoperative exercise. Three parameters of exercise capacity were also compared after intervention: 6MWD (representing lower-limb muscle strength), VO2 peak (representing physical performance), and Borg scores (representing severity of dyspnea).

Search methods

PubMed, Medline, and the Cochrane Library (central) were searched from the earliest date of each to June 2017. The search string used the following keywords and was modified for each database: (“lung cancer” [MeSH] OR non-small-cell lung cancer OR small cell lung cancer) AND (lung surgery OR lobectomy) AND (physical therapy OR physiotherapy OR physical exercise OR physical therapy modalities).

Study selection

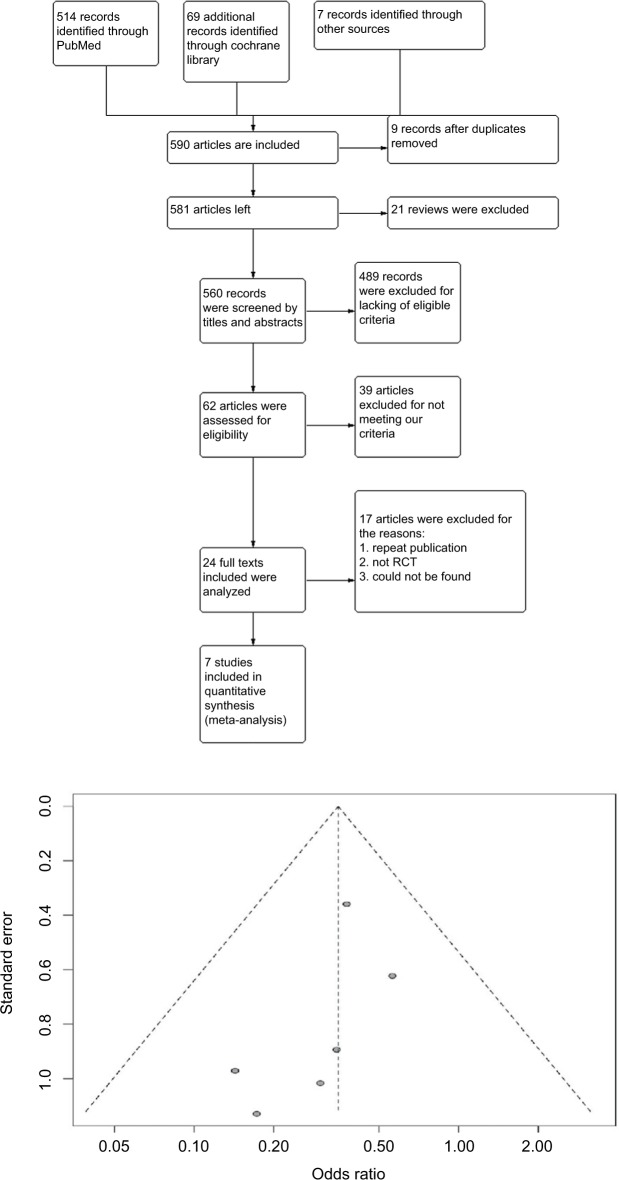

Through reading titles and abstracts, relevant articles were selected for full-text reading. Before this, two authors checked the search results and discussed the final list of the included articles. There was low bias in the included articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection and funnel plot of studies included.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Data extraction

Two authors read the articles and abstracted the data independently, and data were recorded using a predefined evidence table. Outcomes that we concentrated on were PPCs, LOS, and the duration of chest-tube drainage. We summarized information for each study in the list, eg, authors, publication year, type of study, number of participants, specific method of exercise, and index of pulmonary functions before surgery. The use of antibiotics was also clearly recorded.

Risk-of-bias appraisal

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk and Bias Tool, which was developed to evaluate the internal validity of the included RCTs.16 In RevMan 5.0, the tool contains seven criteria: random-sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (report bias), and other risks of bias. The seventh criterion includes fraudulent results, other methodological flaws in RCTs, and the potential for industry bias.17

Statistical analyses

Across all outcomes, a meta-analysis was conducted. Effect estimates are reported as ORs for the dichotomous outcomes. For continuous data, mean difference (MD) was used if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials, and standardized mean difference (SMD) was applied for combining trials measuring the same outcome but using different methods.

For primary outcomes, PPCs were evaluated using pooled RRs with corresponding 95% CIs, and a random-effect model was used to account for potential clinical heterogeneity.18 Forest plots were constructed with RevMan 5.0, and P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Heterogeneity was evaluated by I2: if I2>50%, an article was considered to display substantial heterogeneity, requiring subgroup analysis. To merge the outcomes, the statistic used for analysis was selected for paired analysis. Not all studies supplied complete data. Meanwhile, data that were able to be extracted from existing articles were merged in a forest plot.

Results

Search outcome

Two authors (XL and SLL) performed the literature search, and NW resolved conflicts and discrepancies. The primary literature search produced 590 results, including 20 reviews. After screening of titles and abstracts, 24 studies were found to be possibly relevant and underwent full-text critical appraisal, resulting in 16 exclusions (Table S1). Reasons for exclusion were outcomes recorded not being PPCs and LOS (n=12), no single regular intervention given (n=1), therapy was palliative (n=1), case reports (n=2), and duplicate publication (n=1). We included seven studies (Karenovics et al’s study was a substudy of Licker et al) in the final analysis, as shown in Table 1. All included studies were assessed by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) evidence profile (Table S2). Guidance from GRADE offered a methodology to evaluate the quality of the evidence.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| Studies | Participants | Characteristics | I: n (age ± SD) C: n (age ± SD) |

Intervention | Outcome measurements | Comparison | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (male/female) | Treatment | ||||||

| Lai et al21 | 48 (28/20) | NSCLC (stage I–IV) and COPD; open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 24 (63.13±6.26) C: 24 (64.04±8.94) |

Preoperative exercise (7 days) + pharmacotherapy (atomizing terbutaline, budesonide, and infusion of ambroxol) + intense training (respiratory training and endurance training) | PPCs LOS (postoperative) Duration of antibody use |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower incidence of PPCs (8.3%, 2/24 vs 20.8%, 5/24; P=0.416), had shorter postoperative LOS (6.17±2.91 days vs 8.08±2.21 days, P=0.013), and duration of antibody use (3.61±2.53 days vs 5.36±3.12 days, P=0.032) |

| Pehlivan et al13 | 60 (?/?) | NSCLC (stage IA–IIIB); open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 30 (54.10±8.53) C: 30 (54.76±8.45) |

Preoperative exercise (three times a day), according to patient’s tolerance to exercise speed and time; during the walking exercise, warm-up and cooldown included | PPCs LOS Pulmonary function |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower incidence of PPCs (3.3%, 1/30 vs 16.6%, 5/30; P=0.04); hospital stay found to be significantly shortened by intensive physical therapy (P<0.001) |

| Morano et al14 | 24 (9/15) | NSCLC (stage I–IIIA) and COPD; open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 12 (64.8±8) C: 12 (68.8±7.3) |

Strength and endurance training; control group (breathing exercises for lung expansion) | PPCs LOS Pulmonary function |

Chest physical therapy; CPT – breathing exercises for lung expansion | Patients in the intervention group had lower coincidence of complications (16.7%, 2/12 vs 77%, 7/12; P=0.01) and had shorter LOS (7.8±4.8 vs 12.2±3.6 days) |

| Benzo et al19 | 19 (9/10) Two patients (one in each arm) were missing LOS data | NSCLC (stage I–IIIA) and COPD; open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 10 (70.2±8.61) C: 9 (72.0±6.69) |

Breathing exercise through the device and sustaining that effort as long as they were able, with a goal of 15–20 minutes of daily use; ten face-to-face sessions of treatment in 1 week (twice a day) | PPCs LOS |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower coincidence of complications (33%, 3/9 vs 63%, 5/8; P=0.23), and had shorter LOS (6.3±3.0 vs 11.0±6.3 days) |

| Sekine et al22 | 82 (76/6) | NSCLC (stage I–IV) or COPD; open thoracotomy | I: 22 (70.4±4.6) C: 60 (69.0±5.5) |

Incentive spirometry, abdominal breathing and breathing exercises (with pursed lips, huffing and coughing after nebulizing for 15 minutes with a bronchodilator five times a day), pulmonary exercise for 30 minutes in the rehabilitation room and walking >5,000 steps every day for 2 weeks preoperatively | PPCs LOS |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower coincidence of complications (18.2%, 4/22 vs 28.3%, 17/60), and had shorter LOS (29.0±9.0 vs 21.0±6.8 days; P=0.0003) |

| Karenovics et al20 (substudy of Licker et al) | 151 (91/60) | NSCLC (stage I–III); open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 74 (64±?) C: 77 (64±?) |

5-minute warm-up at 50% peak work rate achieved during CPET; two 10-minute series of 15-second sprint intervals | PPCs LOS in postanesthesia care unit Death |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower coincidence of PPCs (23%, 17/74 vs 44%, 34/77; P=0.018) and a shorter stay in the postanesthesia care unit (median 7 hours, IQ25–75 4–10) |

| Stefanelli et al24 | 40 (23/17) | NSCLC and COPD; lobectomy | I: 20 (<75) C: 20 (<75) |

Group R: intensive preoperative PRP; group S, lobectomy only | VO2 peak | Peak VO2 did not change from T0 to T1 and deteriorated significantly from T1 to T2 | |

| Karenovics et al20 | 151 (91/60) | NSCLC (stage I–III); open thoracotomy or VATS | I: 74 (64±?) C: 77 (64±?) |

5-minute warm-up period at 50% of peak work rate achieved during CPET; two 10-minute series of 15-second sprint intervals | PPCs Pneumonia 6MWD |

Usual care | Patients in the intervention group had lower coincidence of PPCs (23%, 27/74 vs 44%, 39/77; P=0.018). |

Note: “?”= The number of the male and/or female was not clearly recorded in this published article.

Abbreviations: 6MWD, 6-minute walking distance; C, control; CPT, chest physical therapy; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise testing; I, intervention; LOS, length of stay; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; PRP, pulmonary rehablitation programme; PPCs, postoperative pulmonary complications; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

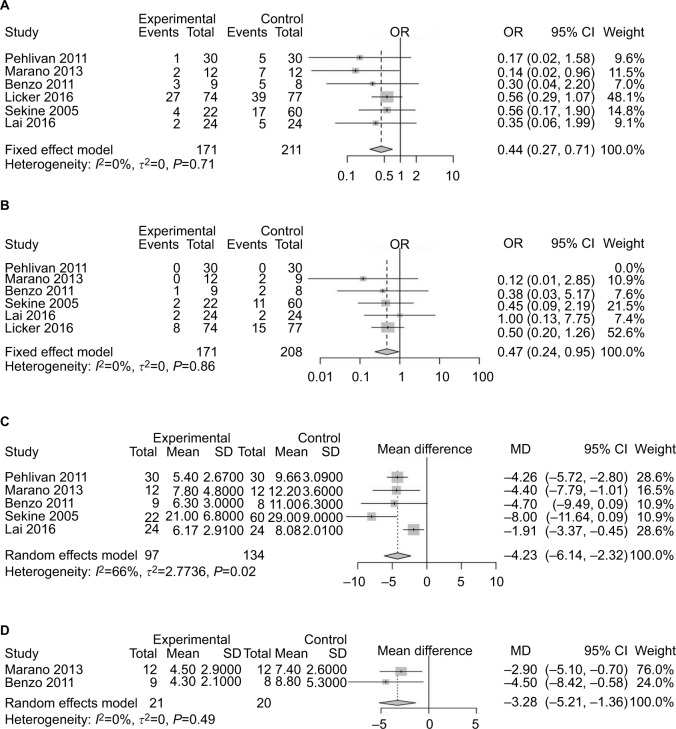

Primary outcomes: PPCs, hospital LOS, chest-drain duration, pneumonia after preoperative exercise

Six studies13,14,19–22 had reported PPCs. Preoperative exercise reduced the risk of complications after surgery (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.27–0.71; Figure 2A). The heterogeneity of this result was acceptable (I2=0, P<0.0001). Five studies8,13,14,21,22 reported postoperative pneumonia. Patients who received preoperative exercise before lung cancer resection had no statistically significant differences in the rate of pneumonia after surgery compared with those receiving usual care only (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.24–0.95; Figure 2B). For LOS, five studies13,14,19,21,22 reported that patients receiving preoperative exercise training had shorter postoperative LOS (SMD −4.23 days, 95% CI −6.14 to −2.32 days; Figure 2C). Two studies14,19 recorded the duration of chest-tube drainage after surgery. Compared with patients receiving preoperative rehabilitation training, patients receiving usual care had a longer duration of chest-tube drainage (MD −3.28 days, 95% CI −5.21 to −1.36 days; Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of comparison: intervention group vs control group in lung cancer patients undergoing resection.

Note: (A) Risk of developing postoperative pulmonary complications; (B) incidence of postoperative pneumonia; (C) postoperative length of hospital stay; (D) duration of chest drainage.

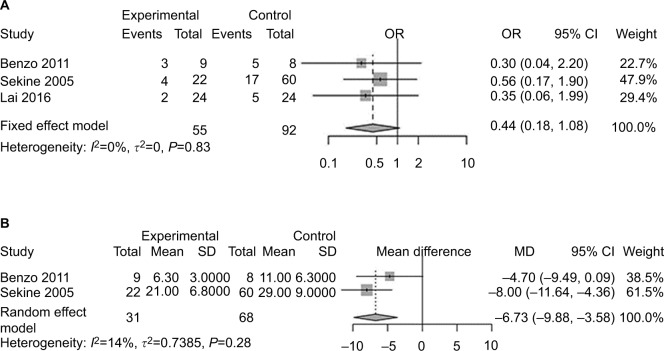

Primary outcomes: PPCs and LOS of patients with lung cancer and COPD

Three studies19,21,22 included patients diagnosed with COPD and lung cancer simultaneously. Statistically, no significant difference was found for PPC incidence between the exercise-intervention group and usual-care group (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.18–1.08; Figure 3A). Two studies19,22 reported LOS of patients with COPD and lung cancer. Patients receiving preoperative exercise had shorter LOS (MD −6.73 days, 95% CI −9.88 to −3.58; Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Forest plots of comparison: intervention group vs control group in lung cancer patients with COPD treated with surgery.

Note: (A) Risk of developing postoperative pulmonary complications; (B) postoperative length of hospital stay.

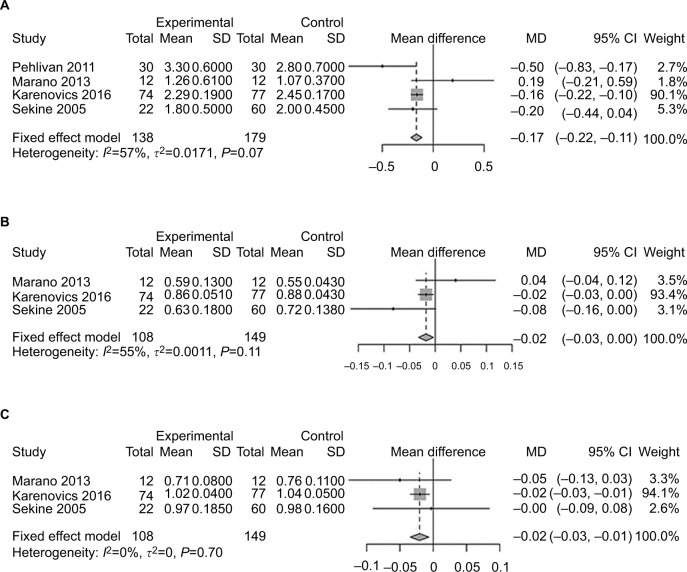

Secondary outcomes: impact of training exercise on pulmonary function capacity and exercise capacity before surgery

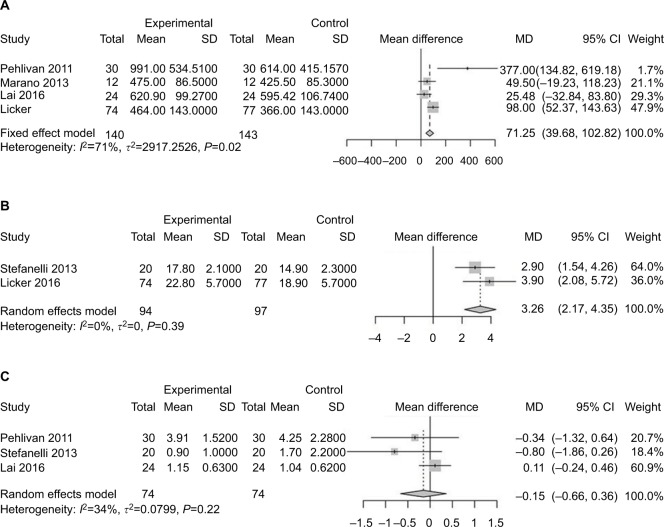

Pulmonary functions of patients in each study are listed in Table 2 and analyzed in Figure 4. There was little difference between the two groups. Three studies analyzed 6MWD,13,14,21 which was considered an index of lower-limb muscle function.23 Patients receiving exercise before surgery reported an improved 6MWD compared with those receiving usual care (SMD 71.25, 95% CI 39.68–102.82; Figure 5A). VO2 peak, reflecting ability of oxygen uptake, was investigated to explore the role of exercise. After training, patients recorded a higher VO2 peak compared to those without training20,24 (SMD 3.26, 95% CI 2.17–4.35; Figure 5B). Patients were less likely to improve in their dyspnea after preoperative exercise therapy13,21,24 (MD −0.15, 95% CI −0.66 to 0.36; Figure 5C).

Table 2.

Summary and comparison of pulmonary function in included studies

| Pulmonary function test | Pehlivan et al13 | Morano et al14 | Karenovics et al20 | Sekine et al22 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual | Rehab | Usual | Rehab | Usual | Rehab | Usual | Rehab | ||||

| FEV1 | 2.8±0.7 | 2.3±0.6 | 1.3±0.3 | 1.3±0.6 | 2.45±0.2 | 2.3±0.2 | 2.0±0.5 | 1.8±0.5 | |||

| FEV1% | – | – | 58.8±13 | 54.8±4.3 | 87.6±4.3 | 85.8±5.1 | 71.6±13.8 | 63.4±18 | |||

| DLCO | 21.3±6.1 | 21.1±6.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| FVC | 3.2±0.8 | 3.1±0.6 | 2.1 (1.5–2.4) | 1.7 (1.7–2.8) | 3.6±0.2 | 3.4±0.2 | 3.1±0.6 | 3.1±0.7 | |||

| FVC% | – | – | 71 (63–89) | 76 (65–79) | 104±5 | 102±4 | 97.7±16 | 94.7±18.5 | |||

Note: Rehab, patients who had received preoperative exercise before thoracic surgery; usual, patients who had received usual care.

Figure 4.

Forest plots of comparison of post-intervention pulmonary function: intervention group vs control group in lung cancer patients undergoing resection.

Note: (A) FEV1; (B) FEV1%; (C) FVC%.

Figure 5.

Forest plots of comparison: intervention group vs control group in lung cancer patients undergoing resection.

Note: (A) Postintervention 6MWD (index of lower-limb muscle strength); (B) VO2 peak (reflecting physical performance); (C) Borg scores (representing dyspnea).

Discussion

Numerous studies with large samples have clearly demonstrated that the presence of COPD is linked with an increase in lung cancer incidence.25 Many patients with lung cancer and COPD will face a significant challenge during the perioperative period. How to guide these patients with COPD before and after cancer surgery with a proper training protocol to improve surgical outcomes remains to be answered. In this meta-analysis, the results imply that preoperative exercise for patients with lung cancer and COPD may be associated with shorter LOS compared with usual care only, but incidence of PPCs remained unchanged even after exercise training. Accompanied by outcome improvement, several parameters of exercise capacity were found to be strengthening after exercise training, such as 6MWD and VO2 peak, because lower-limb muscle capacity was improved with higher ability of oxygen uptake. However, pulmonary function was not enhanced after training.

To date, a consistent protocol for preoperative exercise training has been lacking. Although pulmonary function and muscle-strength enhancement were commonly recorded in all the included studies, detailed methods for exercise training differed in terms of exercise duration and content.

Lai et al21 designed an exercise protocol containing pharmacotherapy and intense-exercise training (respiratory training and endurance training). Notably, the pharmacotherapy in that study was used to relieve symptoms of dyspnea for patients with lung cancer and COPD, which helped patients to complete the exercise training smoothly. In that study, the small sample and patients in the usual-care group having a certain extent of exercise both contributed to a degree of bias.

Meanwhile, Morano et al14 concluded that patients receiving preoperative exercise improved more when compared with those who received chest physical therapy only. The protocol was carefully designed, and contained less extreme endurance training and inspiratory muscle training. The protocol also included flexibility, stretching, and balance exercises in the warm-up and cooldown sections. At the same time, medicine was used to optimize the different preintervention conditions for better comparison. However, patients in the control group received chest physical therapy, which was different from usual care. Another study conducted by Sekine et al reported that COPD patients received breathing-exercise training and walking-exercise training. The reported protocol contained breathing exercises, such as incentive spirometry, abdominal breathing, detailed breathing exercises, and walking exercise, such as walking for 5,000 steps every day.22 Although it was prospectively designed, allocation of the cases in the different groups was not randomized (60 vs 22).

Furthermore, Karenovics et al15 reported an exercise protocol that included 5 minutes of warm-up and cooldown exercises. Patients were guided by a professional exercise physiotherapist. The workload of exercise was adjusted in each session to target near-maximal heart rate toward the end of each set of sprints. Notably, all patients were given advice regarding preoperative education and risk management.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been proven to benefit patients with chronic lung disease, such as COPD.26 Patients with COPD might experience deconditioning and exercise intolerance; therefore, preoperative rehabilitation should target these specific issues to obtain maximum effect. However, the mechanism of effect of exercise on outcome improvement remains unknown. Theoretically, preoperative exercise training is supposed to improve both lung function and muscle strength simultaneously. However, pulmonary function testing in this meta-analysis showed that most of the investigated parameters of pulmonary function were comparable or even slightly lower after exercise, though not significantly. A similar result was reported in other surgical procedures, such as lung transplantation.27 Irreversible lung function after exercise training might represent the severity of the baseline condition of the lung disease and may not be the priority of treatment planning.

Interestingly, skeletal muscle weakness was reported commonly in patients with COPD,28 which raised the question whether targeting muscle capacity may benefit surgical outcome. In this meta-analysis, we found a favorable trend of exercise capacity after training in the Forest plots, which might be related to outcome improvement, represented by improved 6MWD and VO2 peak. A newly published article reported a strong relationship between peak aerobic capacity, lower-limb muscle function, and lung-diffusion capacity. 6MWD is significantly related to lower-limb muscle function, but not to pulmonary function.23 Licker et al15 also reported the importance of VO2 peak in predicting cardiopulmonary complications. There is a lack of uniform recommendations for a training protocol before surgery for patients with lung cancer and COPD; therefore, these results provide positive evidence that a protocol designed to focus on exercise capacity in the future might have an impact on postoperative complications in this group.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, PPCs were set as the main outcome in the analysis. However, different studies had individual definitions of complications, which might have caused bias in counting the PPCs. To reduce this selection bias, we chose those studies defining pneumonia clearly as a standard complication in the analysis, which showed a consistent trend with the overall outcome. Second, the protocol of every study was individually designed and the duration and intensity of exercise varied among the studies. During the process of meta-analysis, the heterogeneity of muscle strength and lung function among studies was still acceptable. Third, the end-point event for preoperative exercise is still obscure among studies, eg, how to decide the outcome of exercise, whether improved or declined, and what the parameters for performance evaluation are, such as lung function and exercise capacity. Exercise-protocol design should be based on information that allows evaluation of the efficacy of the procedure. Fourth, the type of exercise training (aerobic, strength, inspiratory muscle training) and the optimal duration were not consistent in the included studies, which should be balanced against the risk of delaying cancer resection and consequent extension of the disease. Finally, randomized trials on this topic are still scarce, especially for those patients with lung cancer and COPD, which may limit the power of the meta-analysis. In future, more prospective randomized studies are needed to accumulate further evidence.

Conclusion

The goal of the preoperative exercise is to decrease the risk of complications after surgery and enhance recovery, which can ultimately shorten LOS. This meta-analysis provides some evidence of the effect of preoperative exercise on enhanced recovery after surgery for patients with lung cancer and COPD. Future research should pay attention to details of the exercise protocol, such as intensity, duration, and methods, for those patients preparing for surgery.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

Studies excluded in this review

| Study | Research for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Cavalheri et al 20151 | Research for the postoperative exercise |

| Edvardsen et al 20142 | Research for the postoperative exercise |

| Maeda et al 20153 | Duplication; postoperative exercise |

| Sommer et al 20164 | Duplication; Included early postoperative exercise training |

| Esteban et al 20175 | Not RCT |

| Cavalheri et al 20176 | Lacking proper statistics |

| Nai-WenChang et al 20147 | Postoperative walking exercise |

| Missel et al 20158 | Postoperative exercise |

| Jones et al 20079 | Preoperative exercise on cardiopulmonary fitness |

| Valérie et al 201310 | Lacking proper statistics |

| Crandal et al 201411 | Not RCT |

| Wiskemann et al 201612 | Lacking proper statistics |

| FANG et al 201413 | Not RCT |

| Loewen et al 200714 | Not RCT |

| Weiner et al 198415 | Not RCT and Lacking proper statistics |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table S2.

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluations

| Certainty assessment | Patients, n | Effect | Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Preoperative exercise | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | |

| PPCs | |||||||||||

| 63–8 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousb | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 171 | 211 | OR 0.35 (0.21–0.59) | 190 fewer per 1,000 (from 108 fewer to 246 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Pneumonia | |||||||||||

| 53–7 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | Serious | None | 97 | 131 | OR 0.45 (0.16–1.25) | 67 fewer per 1,000 (from 27 more to 106 fewer) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Length of hospital stay | |||||||||||

| 53–7 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousd | None | 97 | 134 | – | SMD 1.02 lower (1.31 lower to 0.74 lower) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Days of chest-tube drainage | |||||||||||

| 23,5 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriouse | None | 21 | 17 | – | MD 3.33 lower (5.35 lower to 1.3 lower) | ⊕⊕⊕⃝ Moderate |

| PPCs of COPD patients | |||||||||||

| 33,6,7 | RCTa | Not seriousa | Not serious | Seriousf | Not serious | None | 9/55 (16.4%) | 27/92 (29.3%) | OR 0.44 (0.18–1.08) | ⊕⊕⊕⃝ Moderate | |

| Length of hospital stay in patients with COPD | |||||||||||

| 23,7 | RCTa | Seriousg | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousd | None | 31 | 68 | – | MD 6.79 lower (9.69 lower to 3.89 lower) | ⊕⃝⃝⃝ Very low |

| 6MWD | |||||||||||

| 34–6 | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 66 | 66 | – | SMD 0.54 higher (0.19 higher to 0.88 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| VO2 peak (reflecting physical performance) | |||||||||||

| 28,9 | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 94 | 94 | – | SMD 0.96 higher (0.66 higher to 1.27 higher) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Borg scores (representing dyspnea) | |||||||||||

| 34,6,9 | RCT | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 74 | 74 | – | SMD 0.54 higher (0.19 higher to 0.88 higher) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

Note:

One of the studies reported by Sekine et al16 was prospective;

PPCs were not defined clearly;

detected by the clinical laboratory index;

length of stay can be influenced by hospital conditions and other nonclinical problems;

duration of drainage was not consistent in different clinical institutes;

different institutes had different definition of PPCs;

small sample of participants;

distance walked influenced by many factors.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; PPCs, postoperative pulmonary complications; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SMD, standardized mean difference.

References

- 1.Cavalheri V, Jenkins S, Cecins N, et al. Patterns of sedentary behaviour and physical activity in people following curative intent treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13:82–85. doi: 10.1177/1479972315616931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edvardsen E, Skjonsberg OH, Holme I, et al. High-intensity training following lung cancer surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70:244–250. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maeda K, Higashimoto Y, Honda N, et al. Effect of a postoperative outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program on physical activity in patients who underwent pulmonary resection for lung cancer. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:550–555. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommer MS, Trier K, Vibe-Petersen J, et al. Perioperative Rehabilitation in Operable Lung Cancer Patients (PROLUCA): A Feasibility Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;15:455–466. doi: 10.1177/1534735416635741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esteban PA, Hernandez N, Novoa NM, et al. Evaluating patients’ walking capacity during hospitalization for lung cancer resection. Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2017;25:268–271. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivx100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavalheri V, Granger CL, Irving LB, et al. Short-term preoperative exercise training: should we expect long-term benefits without postoperative exercise stimulus? European journal of cardiothoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2017;52:1009. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang NW, Lin KC, Lee SC, et al. Effects of an early postoperative walking exercise programme on health status in lung cancer patients recovering from lung lobectomy. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3391–3402. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Missel M, Pedersen JH, Hendriksen C, et al. Regaining familiarity with own body after treatment for operable lung cancer - a qualitative longitudinal exploration. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25:1076–1090. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones LW, Peddle CJ, Eves ND, et al. Effects of presurgical exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness among patients undergoing thoracic surgery for malignant lung lesions. Cancer. 2007;110:590–598. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coats V, Maltais F, Simard S, et al. Home-based rehabilitation program for lung cancer patients. European Respiratory Journal. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crandall K, Maguire R, Campbell A, et al. Exercise intervention for patients surgically treated for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review. Surgical oncology. 2014;23:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiskemann J, Hummler S, Diepold C, et al. POSITIVE study: physical exercise program in non-operable lung cancer patients undergoing palliative treatment. BMC cancer. 2016;16:499. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2561-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang Y, Ma G, Lou N, et al. Preoperative Maximal Oxygen Uptake and Exercise-induced Changes in Pulse Oximetry Predict Early Postoperative Respiratory Complications in Lung Cancer Patients. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2014;103:201–208. doi: 10.1177/1457496913509235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loewen GM, Watson D, Kohman L, et al. Preoperative exercise Vo2 measurement for lung resection candidates: results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 9238. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2007;2:619–625. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074bba7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner P, Man A, Weiner M, et al. The effect of incentive spirometry and inspiratory muscle training on pulmonary function after lung resection. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1997;113:552–557. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekine Y, Chiyo M, Iwata T, et al. Perioperative rehabilitation and physiotherapy for lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Japanese journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery : official publication of the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery = Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai zasshi. 53:237–243. doi: 10.1007/s11748-005-0032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elixigen Company (Huntington Beach, CA, USA) for proofreading. Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development Fund (grant number ZYLX201509), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFC0910700), Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z161100000516063), Beijing Human Resources and Social Security Bureau (Beijing Millions of Talents Project, 2018A05), Special Fund of Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development (No. XMLX201841), Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals’Youth Programme (No. QML20171103), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81502578), and Peking University Medicine Seed Fund for Interdisciplinary Research (BMU2018MX008).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China in 2013: an analysis based on urbanization level. Chin J Cancer Res. 2017;29(1):1–10. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.01.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Licker MJ, Widikker I, Robert J, et al. Operative mortality and respiratory complications after lung resection for cancer: impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and time trends. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1830–1837. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Larrad A, Lascurain-Aguirrebena I, Abecia-Inchaurregui LC, Seco J. Perioperative physiotherapy in patients undergoing lung cancer resection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;19(2):269–281. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer MS, Trier K, Vibe-Petersen J, et al. Perioperative rehabilitation in operation for lung cancer (PROLUCA) – rationale and design. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coats V, Maltais F, Simard S, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a home-based exercise training program before lung resection surgery. Can Respir J. 2013;20(2):e10–e16. doi: 10.1155/2013/291059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobbio A, Chetta A, Ampollini L, et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation in patients undergoing lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33(1):95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benzo R, Wigle D, Novotny P, et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation before lung cancer resection: results from two randomized studies. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(3):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pouwels S, Fiddelaers J, Teijink JA, Woorst JF, Siebenga J, Smeenk FW. Preoperative exercise therapy in lung surgery patients: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2015;109(12):1495–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smetana GW. Postoperative pulmonary complications: an update on risk assessment and reduction. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(Suppl 4):S60–S65. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavalheri V, Granger C. Preoperative exercise training for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD012020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012020.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health-care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pehlivan E, Turna A, Gurses A, Gurses HN. The effects of preoperative short-term intense physical therapy in lung cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(5):461–468. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.11.01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morano MT, Araújo AS, Nascimento FB, et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation versus chest physical therapy in patients undergoing lung cancer resection: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.08.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karenovics W, Licker M, Ellenberger C, et al. Short-term preoperative exercise therapy does not improve long-term outcome after lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(1):47–54. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tricco AC, Cogo E, Holroyd-Leduc J, et al. Efficacy of falls prevention interventions: protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):38. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, et al. Comparisons of interventions for preventing falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1687–1699. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.15006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benzo R, Wigle D, Novotny P, et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation before lung cancer resection: results from two randomized studies. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(3):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karenovics W, Licker M, Ellenberger C, et al. Short-term preoperative exercise therapy does not improve long-term outcome after lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(1):47–54. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai Y, Su J, Yang M, Zhou K, Che G. Impact and effect of preoperative short-term pulmonary rehabilitation training on lung cancer patients with mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2016;19(11):746–753. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2016.11.05. Chinese. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine Y, Chiyo M, Iwata T, et al. Perioperative rehabilitation and physiotherapy for lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;53(5):237–243. doi: 10.1007/s11748-005-0032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burtin C, Franssen FME, Vanfleteren LEGW, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Lower-limb muscle function is a determinant of exercise tolerance after lung resection surgery in patients with lung cancer. Respirology. 2017;22(6):1185–1189. doi: 10.1111/resp.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefanelli F, Meoli I, Cobuccio R, et al. High-intensity training and cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44(4):e260–e265. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houghton AM. Mechanistic links between COPD and lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(4):233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrc3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131(5 Suppl):4S–42S. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pehlivan E, Balcı A, Kılıç L, Kadakal F. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation for lung transplant: effects on pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life; first results in turkey. Exp Clin Transplant. 2018;16(4):455–460. doi: 10.6002/ect.2017.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdulai RM, Jensen TJ, Patel NR, et al. Deterioration of limb muscle function during acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(4):433–449. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0615CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Studies excluded in this review

| Study | Research for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Cavalheri et al 20151 | Research for the postoperative exercise |

| Edvardsen et al 20142 | Research for the postoperative exercise |

| Maeda et al 20153 | Duplication; postoperative exercise |

| Sommer et al 20164 | Duplication; Included early postoperative exercise training |

| Esteban et al 20175 | Not RCT |

| Cavalheri et al 20176 | Lacking proper statistics |

| Nai-WenChang et al 20147 | Postoperative walking exercise |

| Missel et al 20158 | Postoperative exercise |

| Jones et al 20079 | Preoperative exercise on cardiopulmonary fitness |

| Valérie et al 201310 | Lacking proper statistics |

| Crandal et al 201411 | Not RCT |

| Wiskemann et al 201612 | Lacking proper statistics |

| FANG et al 201413 | Not RCT |

| Loewen et al 200714 | Not RCT |

| Weiner et al 198415 | Not RCT and Lacking proper statistics |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table S2.

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluations

| Certainty assessment | Patients, n | Effect | Certainty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Preoperative exercise | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | |

| PPCs | |||||||||||

| 63–8 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousb | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 171 | 211 | OR 0.35 (0.21–0.59) | 190 fewer per 1,000 (from 108 fewer to 246 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Pneumonia | |||||||||||

| 53–7 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | Serious | None | 97 | 131 | OR 0.45 (0.16–1.25) | 67 fewer per 1,000 (from 27 more to 106 fewer) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Length of hospital stay | |||||||||||

| 53–7 | RCTa | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousd | None | 97 | 134 | – | SMD 1.02 lower (1.31 lower to 0.74 lower) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Days of chest-tube drainage | |||||||||||

| 23,5 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriouse | None | 21 | 17 | – | MD 3.33 lower (5.35 lower to 1.3 lower) | ⊕⊕⊕⃝ Moderate |

| PPCs of COPD patients | |||||||||||

| 33,6,7 | RCTa | Not seriousa | Not serious | Seriousf | Not serious | None | 9/55 (16.4%) | 27/92 (29.3%) | OR 0.44 (0.18–1.08) | ⊕⊕⊕⃝ Moderate | |

| Length of hospital stay in patients with COPD | |||||||||||

| 23,7 | RCTa | Seriousg | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousd | None | 31 | 68 | – | MD 6.79 lower (9.69 lower to 3.89 lower) | ⊕⃝⃝⃝ Very low |

| 6MWD | |||||||||||

| 34–6 | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 66 | 66 | – | SMD 0.54 higher (0.19 higher to 0.88 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| VO2 peak (reflecting physical performance) | |||||||||||

| 28,9 | RCT | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 94 | 94 | – | SMD 0.96 higher (0.66 higher to 1.27 higher) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

| Borg scores (representing dyspnea) | |||||||||||

| 34,6,9 | RCT | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Serioush | All plausible residual confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect | 74 | 74 | – | SMD 0.54 higher (0.19 higher to 0.88 higher) | ⊕⊕⃝⃝ Low |

Note:

One of the studies reported by Sekine et al16 was prospective;

PPCs were not defined clearly;

detected by the clinical laboratory index;

length of stay can be influenced by hospital conditions and other nonclinical problems;

duration of drainage was not consistent in different clinical institutes;

different institutes had different definition of PPCs;

small sample of participants;

distance walked influenced by many factors.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; PPCs, postoperative pulmonary complications; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SMD, standardized mean difference.