Abstract

Background:

Alcohol use is highly prevalent and linked to a wide range of negative outcomes among college students. Although emotion dysregulation has been theoretically and empirically linked to alcohol use, few studies have examined emotion dysregulation stemming from positive emotions.

Objective:

The goal of the current study was to extend extant research by using daily diary methods to examine the potentially moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily relation between positive affect and alcohol use to cope with social and non-social stressors.

Methods:

Participants were 165 college students (M age = 20.04; 55.2% male) who completed a baseline questionnaire assessing difficulties regulating positive emotions and responded to questions regarding state positive emotions and alcohol use once a day for 14 days.

Results:

Difficulties regulating positive emotions moderated the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and alcohol use to cope with social stressors, such that positive affect stemming from social stressors predicted alcohol use to cope with social stressors among college students with high (but not low) levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions.

Conclusions:

Findings underscore the potential utility of targeting difficulties regulating positive emotions in treatments aimed at reducing alcohol use to cope with social stressors among college students.

Keywords: positive emotion dysregulation, difficulties regulating positive emotions, positive affect, alcohol use, coping, social stressors

Results of epidemiological studies indicate that alcohol use is highly prevalent among young adults and college students in particular. For instance, findings from a national survey (1) revealed that, in the past 30 days, 59% of full-time college students endorsed alcohol use, 39% endorsed binge drinking (i.e., five or more drinks on the same occasion), and 13% endorsed heavy drinking (i.e., binge drinking on five or more days); these rates were significantly higher than those of young adults not enrolled full-time in college (51%, 33%, and 9%, respectively). College students report various motives for drinking (e.g., enhancement, coping, social, conformity) (2); these have been differentially linked to alcohol consumption and outcomes (3, 4). Understanding drinking to cope among college students is of particular public health relevance and clinical significance. Drinking to cope (i.e., to escape or avoid aversive internal experiences) is associated with more alcohol- (binge drinking, alcohol-related legal problems and absences from school and work; 5–7) and health- (depression, anxiety, personality disorders; 8–10) related negative outcomes compared to other drinking motives among college students, and longitudinal studies have found that adults who drink to cope are at greater risk for developing an alcohol use disorder (11). These aforementioned findings underscore the need for research that explicates predictors of drinking to cope among college students.

Positive affect is one understudied factor that may influence one’s likelihood of drinking to cope. Results of experience sampling studies indicate that college students are more likely to engage in alcohol use on days during which they experience greater positive affect (12–14), and positive affect has been found to serve as a proximal trigger for alcohol use in real-world settings among college students (14, 15). It has generally been assumed in the literature that the link between positive affect and alcohol use is explained by positive reinforcement (16), such that alcohol use serves to elicit, maintain, or enhance positive affect (a presumably desired emotion state). However, while seemingly counterintuitive, there is growing evidence that some college students may engage in efforts to dampen positive emotions (17), suggesting that positive emotions may elicit coping efforts for some college students.

Historically, the stress process has been described in terms of negative emotions, yet, recent studies have found that positive emotions also occur during stressful periods (18). Indeed, stress is defined not by negative emotions, but by physiological and psychological changes that occur in response to novel or threatening stimuli (19); positive emotional experiences may meet these criteria. For instance, there are many examples of events that are experienced as stressful and generate positive emotions (e.g., going on a first date, beginning a new job) (20). Further, positive emotions may elicit physiological and psychological changes that may be experienced as stressful for some people. For instance, for some adults, particular positive emotions (e.g., excitement) may elicit physiological arousal (e.g., racing heart) that is experienced as aversive (21), perhaps through stimulus generalization, whereby fear of physiological arousal originally associated with negative emotional experiences expands to positive emotions (consistent with evidence that individuals may fear positive emotions) (22). This may lead some college students to be non-accepting of some positive emotional states (23). Alternatively, some college students may experience secondary negative affective emotional states in response to situations or stimuli that are typically positive (i.e., negative affect interference) (24). As an example, the experience of joy related to going on a first date may elicit anxiety about doing something embarrassing. Of particular relevance to the current study, alcohol use may be one strategy that some individuals use to cope with positive affect stemming from stressors. Consistent with this assertion, results of recent investigations have found that some adults engage in efforts to suppress positive emotions (25–27), which may take the form of alcohol use. These theoretical accounts and initial studies underscore the need for research on the relation of positive emotions to drinking to cope.

In examining the relation of positive emotions and drinking to cope, it is important to consider the roles of intensity of positive emotions and emotion dysregulation stemming from positive emotions. More recent literature suggests that it is not the intensity of emotions alone that drive health-compromising behaviors (e.g., alcohol use), but instead one’s maladaptive ways of responding to emotions (i.e., emotion dysregulation) (28). Emotion dysregulation has been found to be associated with a wide range of health-compromising behaviors (29, 30), including drinking to cope among college students (31–33). Yet, while research in this area has grown exponentially over the past decade (34, 35), little attention has been paid to the role of difficulties regulating positive (versus negative) emotions in particular in health-compromising behaviors.

College students experience difficulties regulating positive emotions that parallel the difficulties observed in negative emotions (23). For instance, recent research suggests that some college students may be non-accepting of positive emotional states, judging some positive emotions to be undesirable, unpredictable, or frightening (23), perhaps because of deficits in the appraisal or down-regulation of positive emotions (36). Adults who take a judgmental and evaluative stance toward their positive emotions have been found to engage in attempts to suppress positive emotional experiences (25–27), which may include alcohol use (37, 38). College students may also experience difficulties inhibiting impulsive behaviors in the context of positive emotions (23, 39). For instance, intense positive emotions may impair the ability to deliberately control or suppress an automatic response among college students (40, 41); this, in turn, may result in alcohol use (42). Lastly, among college students, positive emotions may interfere with the ability to engage in goal-directed behaviors (23). As an example, positive emotions increase distractibility among college students (43), which may result in disadvantageous decision-making focused on short-term versus long-term goals (44), shown to heighten the risk for alcohol use in adults (45). Yet, despite growing evidence linking difficulties regulating positive emotions to alcohol use, we are aware of only one study that has examined this association. Results of Weiss, Forkus (46) indicate that nonacceptance of positive emotions and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors and engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions are significantly positively associated with alcohol misuse among college students.

The current study aims to address key gaps in the research. First, despite evidence linking positive emotions (14) and difficulties regulating positive emotions (46) separately to alcohol use among college students, no studies have explored their interaction predicting alcohol use outcomes, including drinking to cope. Second, alcohol use among college students has been found to be heightened in social contexts (47), with social stressors in particular predicting alcohol use among adults (48, 49). Yet, a relative dearth of studies have explored the specific contexts in which drinking to cope occurs and their correlates, highlighting the need for studies exploring factors that put college students at risk for coping-related alcohol use, particularly in response to social stressors. Third, a limited number of investigations have used daily diary methods, which reduce error and recall bias and allow for identification of the temporal associations among event-level variables (50), to explore the relations among affect, emotion dysregulation, and/or alcohol use. Addressing the above-mentioned limitations may pinpoint specific targets for alcohol use prevention and intervention programs for college students. Moreover, it would speak to the potential utility of targeting difficulties regulating positive emotions – often overlooked in clinical settings – in interventions aimed at reducing alcohol use in this population.

Thus, the goal of the present manuscript was to extend extant research by exploring the moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social and non-social stressors, separately, and later drinking to cope with social and non-social stressors, separately, in a sample of college students. Based on existing research, it was hypothesized that positive affect stemming from stressors would predict greater likelihood of later drinking to cope with stressors. Further, we expected that difficulties regulating positive emotions would moderate the daily relation between positive affect stemming from stressors and later drinking to cope with stressors. Finally, we expected the strength of these associations to be larger for social versus non-social stressors.

Method

Participants

The final sample was comprised of 165 young adults enrolled in a large public university located in the northeast United States. Participants were almost equally male and female (55.2% male) and their average age was 20.04 (SD = 2.24). In terms of racial/ethnic background, 66.7% of participants self-identified as White, 15.2% as Asian, 6.1% as Black, 5.5% as multiracial, 4.2% as Latino/a, and 2.4% as other. Participant’s average yearly family/household income was $53,158.17. Most participants were full-time students (64.2%) and single (94.5%).

Measures

Experience sampling measures.

Negative and positive affect stemming from stressors.

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (51) was administered to assess negative and positive affect. The PANAS is a well-validated measure of emotional state, and contains 10 positive and 10 negative affect adjectives, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly/not at all, 5 = extremely), where higher scores reflect greater intensity. Negative and positive affect were assessed in relation to social and non-social stressors, separately, that occurred since the previous assessment.

Drinking to cope with stressors.

The following item was utilized to assess drinking to cope with social stressors: “In response to social stressors that occurred during the day, did you drink alcohol?” (yes/no). To assess drinking to cope with non-social stressors, participants were asked: “In response to non-social stressors that occurred during the day, did you drink alcohol?” (yes/no).

Baseline measures.

Difficulties regulating positive emotions.

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive (DERS-P) (23) is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses individuals’ typical levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions, specifically: nonacceptance of positive emotions, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviors when experiencing positive emotions, and difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions. Responses to scores on each item are summed, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties regulating positive emotions. Internal consistency in this sample was good (α = .94).

Procedures

Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the last authors’ university. Participants were recruited using the psychology subject pool, and received course credit for their participation in this study. The study was open to all subject pool participants, but to increase variability in levels of emotion regulation difficulties, people with Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline scale (PAI-BOR) (52) scores above 47 were specifically encouraged to participate via email invitation. This resulted in 38.2% of the sample (n = 63) exceeding the aforementioned PAI-BOR cut-off, suggesting that these individuals display clinically-meaningful borderline personality disorder (BPD) features.

After providing informed consent, questionnaires from the present study were completed online via Qualtrics software. Participants were asked to first complete the baseline assessment measures. Afterwards, they completed the daily assessment measures once daily (i.e., each 24-hour period) for 14 days. Participants were instructed that they could complete assessments at any time during the day, although they were encouraged to do so near the end of the day. Given the aims of the study, participants were asked to specify daily experiences as they related to social (e.g., interpersonal) and non-social (e.g., academic) stressors. At the start of each daily assessment, participants identified the most stressful social event that occurred since the previous reporting period, following which they were asked questions about emotions (i.e., negative and positive) and behaviors (e.g., drinking) associated with this social stressor (i.e., “Please complete the next questions about the social interaction or events that was most stressful”). Following this, participants identified the most stressful non-social event that occurred since the previous reporting period, and were asked to answer the same questions about emotions (i.e., negative and positive) and behaviors (e.g., drinking) associated with this non-social stressor (i.e., “Please complete the next questions about the non-social interaction or events that was most stressful”). Participants were reminded to complete assessments daily via email. They were compensated with course credit, prorated for the proportion of daily assessments completed.

Data Analysis

A series of mixed effects models were tested using R version 3.4.1 software to evaluate same-day predictors of daily alcohol use. The original data set included 184 participants. Participants who did not complete at least two days (n = 19) were excluded from the analyses (new n =165). Participants completed an average of 10.49 (SD = 3.33) days (out of 14 total) over the course of the study. Daily reports comprised level-1 variables nested within person at level-2. All available reports of drinking to cope were included in analyses. Of all the available reports (N = 1,324), drinking to cope with social stressors was reported in 90 (6.6%) reports and drinking to cope with non-social stressors was reported in 69 (5.1%) cases. The primary outcomes (i.e., drinking to cope with social or non-social stressors) were binary, so analyses specified a Bernoulli distribution with a logit link function. All models were initially set with random intercepts and random effects to vary across individuals. Models were run using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Results are presented from population-average models with robust standard errors.

The DERS-P was centered around grand mean. Generalized mixed effects models were used to evaluate the main effect of DERS-P on alcohol use to cope with social and non-social stressors. Regarding the daily positive affect-alcohol use relation, to obtain unbiased estimates of the pooled within-person slopes, the level 1 predictor (positive affect) was person-mean centered and the person means were entered at level 2 to examine between-person variability. We examined positive affect as a predictor of later alcohol use using the basic level-1 model shown below.

Where Pit is the probability of person i’s drinking to cope on day t; π0i is the intercept, which estimates person i’s log odds of drinking to cope when other predictors are zero; π1i – π2i are the partial within-person regression coefficients for person i; and eit is a random residual component which is the error term.

To examine the moderating effect of the DERS-P on the daily relation between positive affect and drinking to cope, cross-level interactions were tested where the DERS-P was added as a level-2 predictor of the level-1 coefficient (positive affect):

where B11 is the coefficient for the effect of the DERS-P on the relation between daily positive affect and drinking to cope.

Two sets of these models were run to explore the relations of these variables in relation to social and non-social stressors separately. To examine social stressors, we examined the relations among positive affect stemming from social stressors, DERS-P, and drinking to cope with social stressors. To examine non-social stressors, we examined the relations among positive affect stemming from non-social stressors, DERS-P, and drinking to cope with non-social stressors. Finally, moderation analyses were re-run controlling for negative affect given evidence for interdependence of negative and positive emotions (53) and descriptive data and moderation analyses were presented for individuals with and without BPD features, measured with the PAI-BOR.

Results

Descriptive data are presented in Table 1. Drinking to cope with social and non-social stressors was endorsed by 27.3% and 20.0% of participants, respectively. In the basic model, positive affect stemming from social stressors was not a significant predictor of later drinking to cope with social stressors, B = −.014, SE = .02, t(163) = −0.65, p = .52, and positive affect stemming from non-social stressors was not a significant predictor of later drinking to cope with non-social stressors, B = −.044, SE = .03, t(163) = −1.61, p = .11. However, difficulties regulating positive emotions were significantly associated with drinking to cope with social stressors, B = 0.084, SE = 0.03, t(163) = 2.45, p = 0.014, and trending toward significance for non-social stressors, B = 0.086, SE = 0.04, t(163) = 1.92, p = 0.055.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for the Primary Study Variables.

| n | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average positive affect stemming from social stressors at the person-level | 165 | 16.63 | 5.48 | 10, 38.57 |

| Average positive affect stemming from non-social stressors at the person-level | 165 | 19.43 | 6.47 | 10.5, 44.62 |

| DERS-Positive | 165 | 18.73 | 7.24 | 13, 46 |

Note. DERS-Positive = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive.

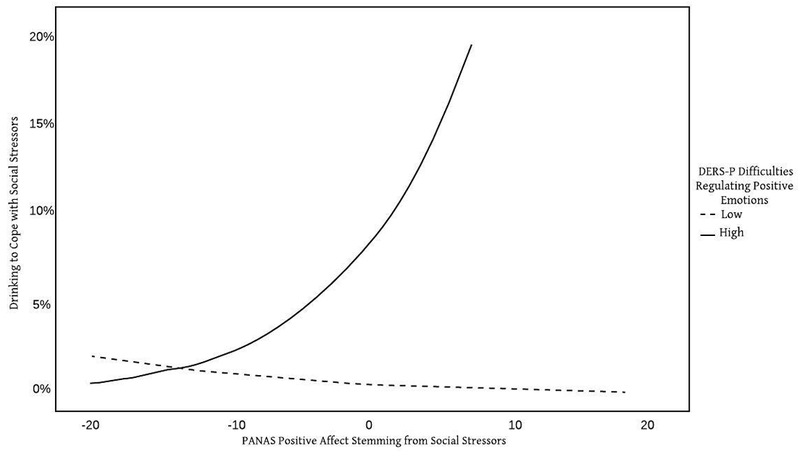

A series of models were conducted to explore the moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily relation between positive affect and drinking to cope. First, we explored the influence of the interaction between positive affect stemming from social stressors and difficulties regulating positive emotions on later drinking to cope with social stressors. Difficulties regulating positive emotions was a significant moderator of the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and later drinking to cope with social stressors, B = .045, SE = .02, t(163) = 2.23, p = .02. Results suggest that at high levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions, higher positive affect stemming from social stressors was associated with higher probability of drinking to cope with social stressors (see Figure 1). Conversely, at low levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions, positive affect stemming from social stressors was not significantly associated with the probability of drinking to cope with social stressors.

Figure 1.

Interaction between Positive Affect Stemming from Social Stressors and Difficulties Regulating Positive Emotions Predicting Drinking to Cope with Social Stressors

Note. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. DERS-P = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale - Positive. Difficulties regulating positive emotions were found to moderate the relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and drinking to cope with social stressors was significant at high (but not low) levels of difficulties regulating positive emotions.

Next, we explored the influence of the interaction between positive affect stemming from non-social stressors and difficulties regulating positive emotions on later drinking to cope with non-social stressors. No significant relationship was found for the moderating effect of difficulties regulating positive emotions on the daily relation between positive affect stemming from non-social stressors and drinking to cope with non-social stressors, B = .023, SE = .02, t(163) = 1.15, p = .25.

Secondary Analyses

Moderation models were re-run controlling from negative affect. The strength and direction of findings for social, B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, t(162) = 2.43, p = 0.02, and non-social, B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t(162) = 1.11, p = .27, stressors remained the same.

Given the large number of participants with high levels of BPD features, analyses were conducted to describe and explore the primary study variables among individuals with high versus low BPD features. See Table 2 for descriptive statistics and between-group differences in the primary study variables among individuals with high and low BPD features. Individuals with high BPD features reported significantly more difficulties regulating positive emotions. Moderation analyses were then conducted among individuals with high and low BPD features separately. Difficulties regulating positive emotions was a significant moderator of the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and later drinking to cope with social stressors among individuals with high, B = .09, SE = .04, t = 2.00, p = .045, but not low, B = .04, SE = .04, t = 0.93, p = .35, BPD features. As was found in the overall sample, difficulties regulating positive emotions was not a significant moderator of the daily relation between positive affect stemming from non-social stressors and later drinking to cope with non-social stressors among individuals with high, B = −.06, SE = .07, t = −0.85, p = .40, and low, B = −.06, SE = .15, t = −0.39, p = .70, BPD features.

Table 2.

Primary Study Variables among the Probable BPD and no-BPD Groups

| Probable BPD (n = 63) | No-BPD (n = 102) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | Test Statistic | |

| 17.57 (5.61) | 16.04 (5.35) | t(126.52) = −1.73, p = 0.09 | |||

| Average positive affect stemming from non-social stressors at the person-level | 17.26 (5.33) | 15.68 (4.94) | t(123.72) = −1.91, p = 0.06 | ||

| DERS-Positive | 22.38 (8.45) | 16.47 (5.27) | t(92.08) = −4.98, p < .001 | ||

| Average days of drinking to cope with social stressors at the person-level | 58 (11.30%) | 32 (3.7%) | t(101.56) = −1.15, p = 0.14 | ||

| Average days of drinking to cope with non-social stressors at the person-level | 47 (9.2%) | 22 (2.7%) | t(98.115) = −1.48, p = 0.14 | ||

Note. DERS-Positive = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation – Positive.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to identify the potential moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social and non-social stressors and later drinking to cope with social and non-social. Findings provide support for an interaction between positive affect stemming from social stressors and difficulties regulating positive emotions predicting drinking to cope with social stressors, such that college students were more likely to use alcohol to cope with social stressors following high positive affect if they reported greater difficulties regulating positive emotions. This pattern of findings did not extend to non-social stressors, underscoring the role of social context in the associations among positive affect, difficulties regulating positive emotions, and drinking to cope. Our results have important implications for prevention and intervention efforts aimed at reducing alcohol use among college students.

The present findings align with a growing body of research highlighting the role of deficits in individual’s responses to positive emotional experiences in health-compromising behaviors, including alcohol use (46, 54–57). Regarding difficulties regulating positive emotions in particular, results of extant investigations indicate that higher levels of nonacceptance of positive emotions (46), difficulties controlling impulsive behaviors when experiencing positive emotions (46, 54, 56, 57) (as assessed by the overlapping constructs of DERS-P Impulse, UPPS-P Positive Urgency, and Risky Behavior Questionnaire Positive) (23, 39, 54), and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when experiencing positive emotions (46) are associated with greater alcohol use. Our findings extend these aforementioned studies by providing support for the moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and drinking to cope with social stressors. These findings suggest the importance of contextual differences in drinking, such that the moderating effect of difficulties regulating positive emotions only pertained to drinking as a form of coping with social (but not non-social) stressors. Future research is needed to better understand the role of context in the relations among positive affect, difficulties regulating positive emotions, and alcohol use. Experience sampling studies that assess within-person variability in difficulties regulating positive emotions may point to specific contexts in which coping-related alcohol use is likely to occur. For instance, it is possible that, in response to social stressors, college students’ difficulties regulating positive emotions may worsen. Investigations are also needed to examine the social stressors with greater specificity (e.g., rejection, peer pressure, teasing/bullying).

Results of the current study indicate that college students are more likely to drink to cope following high levels of positive affect if they experience greater difficulties regulating positive emotions. These findings underscore the potential utility of improving the ability to regulate positive emotions through prevention and intervention programs aimed at reducing alcohol use among college students. For instance, distress tolerance skills may improve behavioral control when experiencing positive emotions by redirecting attention to non-emotional stimuli and promoting more adaptive actions in the context of positive emotions. Similarly, targeting emotional acceptance and willingness may reduce urgency stemming from positive emotions by increasing tolerance for previously-avoided emotions. Indeed, treatments that target the aforementioned domains have been found to result in reductions in substance use (58–61). Future investigations are needed to examine whether these treatments lead to fewer difficulties regulating positive emotions, and whether these reductions result in less alcohol use.

Finally, approximately one-third of our sample scored above the cut-off score for high BPD features on the PAI-BOR. Individuals with high levels of BPD features were found to exhibit more difficulties regulating positive emotions, consistent with evidence that individuals with BPD exhibit positive emotional disturbance, such as greater suppression of positive emotions (27), more difficulties controlling impulsive behavior in the context of positive emotions (62), and lower levels of positive emotion differentiation (63). Moreover, our results suggest that difficulties regulating positive emotions significantly moderated the daily relation between positive affect stemming from social stressors and later drinking to cope with social stressors among individuals with high, but not low, levels of BPD features. This finding suggests the potential importance of difficulties regulating positive emotions to our understanding of the positive affect-alcohol use relation in the context of social stressors among individuals with high BPD features in particular. For instance, our results may suggest the utility of assessing difficulties regulating positive emotions among individuals with high BPD features as a means of identifying risk for alcohol use in the context of social stressors and targets for alcohol use prevention and intervention. Of note, in interpreting the above findings, it warrants mention that our measure of BPD features is not intended to be a diagnostic tool; scores above the cut-off simply indicate difficulties with some symptoms that overlap with BPD, such as affect instability (including difficulties regulating emotions), identity disturbance, negative relationships, and self-harm. It is not surprising that difficulties regulating positive emotions were found to be particularly relevant to individuals that scored high on the PAI-BOR, as affect disturbance is a primary defining feature of the measure. Research is needed to better understand the nature and consequences of difficulties regulating positive emotions among individuals with BPD, including their scores on the DERS-P, compared to their non-BPD counterparts.

Although results of the present study add to the literature on the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the relation between daily positive affect and drinking to cope, several limitations warrant mention. First, this study involved a homogeneous, nonclinical sample of participants, many of whom had high BPD features. While analogue samples have important strengths, such as identifying vulnerabilities to the initial development of clinical phenomena (64), replication of these findings in larger, more diverse samples is needed. Second, this study was limited by the timing and type of measures. For instance, the same-day monitoring period of predictor and outcome precluded determination of the temporal relations among positive affect, difficulties regulating positive emotions, and drinking to cope. Further, overall rates of alcohol use were likely much higher in this sample as individuals may have used alcohol for reasons beyond coping (65). In addition, the focus of the current study was on social and non-social stressors (versus other contexts). Moreover, given the nature of the study (i.e., daily assessment), to reduce participant burden, drinking to cope was only assessed with two items and used a yes/no scale. Also, positive affect was assessed with the PANAS, which does not assess low arousal positive emotions (e.g., relaxation). Finally, we did not assess when the stressor occurred in relation to the daily assessment. For some participants, it is possible that the stressor was ongoing, or at its height, which may have influenced responding. The above-mentioned limitations constitute important areas for future research.

Despite limitations, results of the present study extend extant research on the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the positive affect-alcohol use relation. This is the first study to use an experience sampling design to identify the relations among positive affect, difficulties regulating positive emotions, and drinking to cope. Findings provide support for the moderating role of difficulties regulating positive emotions in the daily association between positive affect stemming from social stressors and later drinking to cope with social stressors, underscoring potential targets for interventions and preventions aimed at reducing alcohol use among college students.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Work on this paper by the first author was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants K23DA039327 and L30DA038349

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial conflicts

Contributor Information

Nicole H. Weiss, University of Rhode Island, 142 Flagg Rd, Kingston, RI 02881, nhweiss7@gmail.com

Megan M. Risi, University of Rhode Island, 142 Flagg Rd, Kingston, RI 02881, mrisi@uri.edu

Krysten W. Bold, Yale University School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511, krysten.bold@yale.edu

Tami P. Sullivan, Yale University School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511, tami.sullivan@yale.edu

Katherine L. Dixon-Gordon, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 135 Hicks Way, Amherst, MA 01003-9271, katiedg@gmail.com

References

- 1.Abuse Substance and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Németh Z, Urbán R, Kuntsche E, San Pedro EM, Nieto JGR, Farkas J, et al. Drinking motives among Spanish and Hungarian young adults: a cross-national study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46:261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuntsche EN, Kuendig H. Do school surroundings matter? Alcohol outlet density, perception of adolescent drinking in public, and adolescent alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant VV, Stewart SH, Mohr CD. Coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives predict different daily mood-drinking relationships. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:226–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1997;58:100–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2002;63:486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tragesser SL, Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking motives as mediators in the relation between personality disorder symptoms and alcohol use disorder. Journal of personality disorders. 2008;22:525–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armeli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armeli S, Todd M, Conner TS, Tennen H. Drinking to cope with negative moods and the immediacy of drinking within the weekly cycle among college students. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2008;69:313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beseler CL, Aharonovich E, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Adult transition From at-risk drinking to alcohol dependence: The relationship of family history and drinking motives. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:607–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swendsen JD, Tennen H, Carney MA, Affleck G, Willard A, Hromi A. Mood and alcohol consumption: An experience sampling test of the self-medication hypothesis. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2000;109:198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2004;65:126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2005;66:459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: Effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A, Barber LL, Wolf S. Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. Sher KJ, editor. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016. 375 p. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman GC, Joormann J, Johnson SL. Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive therapy and research. 2008;32:507–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folkman S The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety, stress, and coping. 2008;21:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appley MH, Trumbull RA. Dynamics of stress: Physiological, psychological and social perspectives. New York, NY: Plentum Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1967;11:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor S, Koch WJ, McNally RJ. How does anxiety sensitivity vary across the anxiety disorders? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:249–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg CZ, Shapiro N, Chambless DL, Ahrens AH. Are emotions frightening? II: An analogue study of fear of emotion, interpersonal conflict, and panic onset. Behaviour research and therapy. 1998;36:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss NH, Gratz KL, Lavender J. Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior modification. 2015;39:431–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frewen PA, Dean JA, Lanius RA. Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: Development of the Hedonic Deficit and Interference Scale. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2012;3:8585-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roemer L, Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Wagner AW. A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. Journal of traumatic stress. 2001;14:149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beblo T, Fernando S, Klocke S, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, Driessen M. Increased suppression of negative and positive emotions in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;141:474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beblo T, Fernando S, Kamper P, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, Pastuszak A, et al. Increased attempts to suppress negative and positive emotions in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry research. 2013;210:505–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gratz KL, Tull MT. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments In: Baer RA, editor. Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2010. p. 105–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky behaviors among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence: The influence of negative and positive urgency. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;155:147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26:453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM. Emotion dysregulation and coping drinking motives in college women. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38:553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veilleux JC, Skinner KD, Reese ED, Shaver JA. Negative affect intensity influences drinking to cope through facets of emotion dysregulation. Personality and individual differences. 2014;59:96–101. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandley RB, Luebbe AM, Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM. Anxiety sensitivity, coping motives, emotion dysregulation, and alcohol-related outcomes in college women: A moderated-mediation model. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2014;75(1):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss NH, Sullivan TP, Tull MT. Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;3:22–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP. Emotion dysregulation and risky, self-destructive, and health compromising behaviors: A review of the literature. Bryant ML, editor. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carl JR, Soskin DP, Kerns C, Barlow DH. Positive emotion regulation in emotional disorders: A theoretical review. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33:343–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological review. 2004;111:33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological assessment. 2007;19:107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billieux J, Gay P, Rochat L, Van der Linden M. The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour research and therapy. 2010;48:1085–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. The relationship between self-report and lab task conceptualizations of impulsivity. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46:121–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noël X, Paternot J, Van der Linden M, Sferrazza R, Verhas M, Hanak C, et al. Correlation between inhibition, working memory and delimited frontal area blood flow measured by 99MTC–bicisate spect in alcohol–dependent patients. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;36:556–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dreisbach G, Goschke T. How positive affect modulates cognitive control: Reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;30:343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slovic P, Finucane ML, Peters E, MacGregor DG. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis. 2004;24:311–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bechara A, Dolan S, Denburg N, Hindes A, Anderson SW, Nathan PE. Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychologia. 2001;39:376–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiss NH, Forkus SR, Contractor AA, Schick MR. Difficulties regulating positive emotions and alcohol and drug misuse: A path analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;84:45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical psychology review. 2003;23:719–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abrams K, Kushner MG, Medina KL, Voight A. Self-administration of alcohol before and after a public speaking challenge by individuals with social phobia. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas SE, Bacon AK, Randall PK, Brady KT, See RE. An acute psychosocial stressor increases drinking in non-treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKay JR. Studies of factors in relapse to alcohol, drug and nicotine use: a critical review of methodologies and findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(4):566–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morey LC. The Personality Assessment Inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell JA, Carroll JM. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological bulletin. 1999;125:990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Assessing the negative and positive emotion-dependent nature of risky behaviors among substance dependent patients. Assessment. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss NH, Bold KW, Contractor AA, Sullivan TP, Armeli S, Tennen H. Trauma exposure and heavy drinking and drug use among college students: Identifying the roles of negative and positive affect lability in a daily diary study. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;79:131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol Use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:1441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG, Lilienfeld SO. Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological assessment. 2015;27:1129–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown RA, Reed KMP, Bloom EL, Minami H, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, et al. Development and preliminary randomized controlled trial of a distress tolerance treatment for smokers with a history of early lapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dimeff LA, Rizvi SL, Brown MZ, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abuse: A pilot application to methamphetamine-dependent women with borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2000;7:457–68. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Linehan MM, Schmidt H, Dimeff LA, Craft JC, Kanter J, Comtois KA. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. The American Journal on Addictions. 1999;8:279–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Bissett R, Piasecki M, Batten SV, et al. A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behavior therapy. 2004;35:667–88. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peters JR, Upton BT, Baer RA. Relationships between facets of impulsivity and borderline personality features. Journal of personality disorders. 2013;27:547–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, Weiss NH, Rosenthal MZ. A preliminary examination of the role of emotion differentitation in the relationship between borderline personality disorder and maladaptive behaviors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2014;36:616–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tull MT, Bornovalova MA, Patterson R, Hopko DR, Lejuez CW. Handbook of research methods in abnormal and clinical psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1988;97:168–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]