Abstract

The majority of modifiable health outcomes are attributable to factors that are outside the direct reach of the health systems and can only be reached through intersectoral actions. In recent years, Iran implemented a series of reforms in the health sector called Health Transformation Plan (HTP). This paper aimed to review health-related intersectoral actions in Iran that have focused on interventions conducted after HTP implementation and to compare the interventions against the recommendations by World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Findings showed that intersectoral governance interventions are the strongest points and have the most compatibility with the recommendations, while intersectoral environmental interventions are the weakest points. Also, many of the interventions have not yet been completely implemented. Moreover, continuity and sustainability of the policies and programs are still a concern.

Keywords: Intersectoral collaboration, Health care reform, Universal health coverage, Iran

↑ What is “already known” in this topic:

The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health (SDH) has devised a series of evidence-based intersectoral actions to equitably and sustainably promote health.

→ What this article adds:

In I.R. Iran, intersectoral governance interventions are the strongest points and have the most compatibility with the recommendations, while intersectoral environmental interventions are the weakest points.

The ultimate goal of health systems is to help people attain the highest equitable health status through Universal Health Coverage (UHC) (1). However, it is estimated that medical care can only account for about 10%-20% of the modifiable health outcomes (2). Others are attributable to social, economic, and behavioral factors that are outside the direct reach of the health systems. Therefore, intersectoral actions could be highly important in approaching and dealing with these factors.

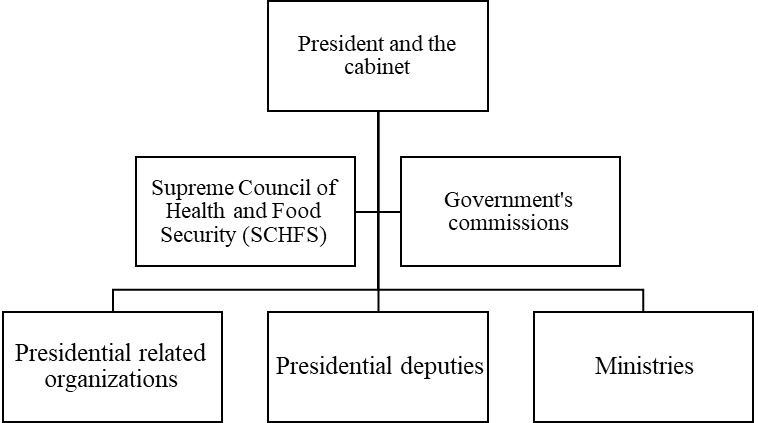

World Health Organization (WHO) defines intersectoral actions as “the alignment of strategies and resources between actors from two or more policy sectors to achieve complementary objectives” (3). In I.R Iran, health-related intersectoral affairs are technically the responsibility of the Supreme Council of Health and Food Security (SCHFS). Founded in 2005, this council is headed by the president, and 13 ministers of the cabinet are prominent members including min isters of “Health and Medical Education”, “State”, “Education”, “Youth and Sports”, “Cooperation, Labor and Social Welfare”, “Agriculture”, and “Industry, Mining, and Trade”. The Minister of Health is the secretary of the council. SCHFS secretariat is established in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME), with corresponding secretariats in the provinces (4) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Position of Supreme Council of Health and Food Security (SCHFS) in Iran state structure. Adopted from (5)

In May 2014, the Iranian MoHME began a series of reforms by launching multiple interventions in the health sector called Health Transformation Plan (HTP) (6-8). Although HTP was initially started in the treatment sector, it was continued to cover other sectors of the health system.

One of the important interventions conducted by the MoHME following HTP implementation was the establishment of the Deputy for Social Affairs and its subordinate departments in 2016. The secretariat office of SCHFS is currently located in the Deputy for Social Affairs and is the hub for integrating and organizing the interventions of the health system in the field of intersectoral collaborations.

The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health has recommended a series of evidence-based intersectoral actions (9). In this paper, health-related intersectoral actions in Iran were reviewed, with a focus on interventions conducted after HTP implementation, and interventions were compared against recommendations. The classification proposed by Pega et al was used in this study to better present the findings (10). This categorization focuses on determinants of health and is related to sustainable development goals (SDGs) and equity and sustainable development foci. Data were collected by reviewing published and unpublished documents. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of health-related intersectoral actions conducted in Iran considering the recommendations by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health .

| Recommendations by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health | Examples of interventions conducted after the implementation of the Health Transformation Plan (HTP) in Iran |

| A) Intersectoral governance interventions | |

| A.1. The local government and civil society, backed by national government, has established local participatory governance mechanisms that enable communities and the local government to partner in building healthier and safer cities. |

A.1.1. Establishing Provincial Health Policy Secretariats (PHPSs) in the organizational structure of provincial

universities of medical sciences. One of the main functions of the PHPSs as supporting bodies is to

ensure community participation and intersectoral cooperation in the policymaking processes aiming to improve

health indicators in the provinces, emphasizing on Social Determinants of Health (SDH) (11).

A.1.2. Establishing a community-based council called “Civil Society Participation House in Health (CSPHH)” as a substructure of the Secretariat of Health Policymaking, with the aim of empowering people to cooperate in promoting their health and their environment(12). A.1.3. Designing and implementing national educational workshops for members of CSPHH with the aim of promoting their health literacy and equipping them with the required skills for cooperating in the participatory decision-making process at the provincial levels. A.1.4. Producing practical instructions, such as guidelines, for health mediators with the aim of allowing CSPHH members to be acquainted with health-related concepts and their potential roles in health promotion. A.1.5. Developing high-level policy documents based on SDH approach in provincial level called “Provincial Health Plan” under the supervision of Secretariats of Health Policymaking and with the cooperation of CSPHH members and all relevant non-health organizations. The plan was first piloted in Qazvin province (12). A.1.6. Establishing Health Assemblies in different levels form local to national level, with the aim of providing opportunities for all members of civil societies, private and public sectors to gather, share, and discuss common health-related problems annually. A.1.7. Establishing a community-based center called “Neighborhood Health Center” as a gathering place for people living in a neighborhood to talk about their health-related problems and take participatory actions to solve them in the neighborhood. A.1.8. Implementing a predesigned systematic monitoring system for Council of Health and Food Security (SCHFS) decrees and the performance of the provincial secretariats by the SCHFS secretariat. |

| A.2. Parliament and equivalent oversight bodies adopt a goal of improving health equity through action on the social determinants of health as a measure of government performance. |

A.2.1. Passing the act of “permanent activities of SCHFS” in the parliament as the only intersectoral council

responsible for improving the SDH through sectoral and intersectoral policymaking.

A.2.2. The obligation of the government to address different problems rooted in the unequal distribution of the SDH in several articles of the Sixth Development Plan of the country. Each article addressed the relevant organizations responsible for each determinant, including unemployment, social support, food. A.2.3. Addressing the realization of comprehensive health approach in General Health Policies announced by Supreme Leader (13). |

| A.3. National government establish a whole-of-government mechanism that is accountable to parliament, chaired at the highest political level possible. |

A.3.1. Developing an intersectoral multilevel decision-making structure within the SCHFS

secretariat, including intersectoral technical committees, technical workgroups, permanent

commission, and the SCHFS itself, each with assigned responsibilities and decision-making

authorities.

A.3.2. Empowering the SCHFS through establishing a Health Secretariat in each governmental organization as the substructure of the SCHFS secretariat in non-health organizations toward realizing Health in All Policies (HiAP) paradigm. |

| A.4. The monitoring of social determinants and health equity indicators be institutionalized and health equity impact assessment of all government policies, including finance, be used. |

A.4.1. Obligating the SCHFS secretariat to define and monitor the major indicators for health

and food security based on SDH approach (14);

A.4.2. Passing a decree in SCHFS toward establishing a national observatory system for health equity based on a list of 69 predefined indicators from the very local levels of the country, in association with the Management and Planning Organization (MPO), SCHFS secretariat, Statistical Centre of Iran, and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). A.4.3. Implementing Health Impact Assessment (HIA) to assess the impact of major national projects on different aspects of population health, including health equity. |

| A.5. National and local governments and civil society establish a cross-government mechanism to allocate budget to action on social determinants of health. | A.5.1. Establishing Health Charity Assemblies in national and provincial levels with the aim of pooling and directing funds raised toward health promotion projects with the specific focus on actions on SDH redistribution (15, 16). |

| A.6. Public resources are equitably allocated and monitored between regions and social groups, for example, using an equity gauge. | A.6.1. Allocating public fund resources of family physician programs to different geographical regions according to their deprivation degrees in different form (health team salary, reward, per capita, etc.). |

| A.7. Government policy-setting bodies ensure and strengthen the representation of public health in domestic and international economic policy negotiations. | |

| A.8. Governments pass and enforce legislation that promotes gender equity and makes discrimination based on sex illegal. |

A.8.1. Addressing gender equity in different terms, including gender discrimination in article

19 of the constitutions, which obligates all developmental sectors to address this issue in their

sectoral and intersectoral policies.

A.8.2. Addressing gender specific health needs in 2 different policy documents titled as “Men Health Policy and Women Health Policy”, with the aim of restructuring health service provision system according to their specific heath needs. A.8.3. Passing the act of Family Protection by the Parliament. |

| A.9. Governments are set up within the central administration and provide adequate and long-term funding for a gender equity unit that is mandated to analyze and to act on the gender equity implications of policies, programs, and institutional arrangements. | A.9.1. Obligation of all governmental organizations to organize and strengthen the organizational status of women and family affairs in their organization through implementing gender equity in policies and programs and analyzing their impact on gender inequity based on predefined indicators announced by National Headquarters of Woman and Family, in Sixth Development Plan of Iran. |

| A.10. National government strengthens the political and legal systems to ensure they promote the equal inclusion of all. | |

| A.11. National government acknowledges, legitimizes, and supports marginalized groups, in particular indigenous people, in policy, legislation, and programs that empower people to represent their needs, claims, and right. | A.11.1. Emphasizing the needs of deprived and vulnerable groups in Sixth Development Plan of Iran and General Health Policies announced by Supreme Leader. |

| A.12. National and local-level government ensures the fair representation of all groups and communities in decision-making that affects health and in subsequent program and service delivery and evaluation. | A.12.1. Involving all relevant stakeholders from different groups, including civil societies and non-governmental communities in the policy-making process in intersectoral multilevel decision-making structure of SCHFS at both national and provincial levels (eg, health assemblies, technical committees and workgroups). |

| A.13. Support for civil society to develop, strengthen, and implement health equity-oriented initiatives. | A.13.1. Establishing a specific mission-oriented office called “non-governmental organizations (NGOs)” for health as a substructure of the Deputy for Social Affair in MOHME, with the aim of identifying and empowering all active health related NGOs. |

| A.14. Governments ensure that all children are registered at birth without financial cost to the household | |

| A.15. National governments establish a national health equity surveillance system, with routine collection of data on social determinants of health and health inequity. | A.15.1. Passing a decree in SCHFS toward establishing a national surveillance system of health equity based on a list of predefined 69 indicators to measure health inequity from the very local levels of the country, with the cooperation of Plan and Budget Organization, SCHFS secretariat, National Center for Statistics of Iran, and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). |

| A.16. Governments build capacity for health equity impact assessment among policymakers and planners across government departments. |

A.16.1. Establishing Health Secretariats in non-health governmental organizations as the

substructure of the SCHFS secretariat toward realizing HiAP Paradigm through constant

monitoring of policy contents and processes.

A.16.2. Planning to hold different national capacity building workshops for non-health organizations representatives participating in intersectoral multilevel decision-making structure of SCHFS, with the aim of informing them about their potential impacts on SDH, with the collaboration of WHO. |

| A.17. Governments include the economic contribution of household work, care work, and voluntary work in national accounts and strengthen the inclusion of informal work. | A.17.1. Conducting a survey by the Iranian Monetary and Banking Research Institute (MBRI) to calculate the value of the unpaid work, including the household work and care work as the percentages of GDP. |

| B) Intersectoral socioeconomic interventions | |

| B.1. Build comprehensive package of quality early child development programs and services for children, mothers, and other caregivers, regardless of ability to pay. | B.1.1. Developing the national policy document for early child development (ECD) by MOHME with the collaboration of Ministry of Education and Welfare Organization and piloting it in 4 different districts of the country (17). |

| B.2. Provide quality education that pays attention to children’s physical, social/emotional, and language/ cognitive development, starting in preprimary school. |

B.2.1. Addressing the provision of quality education for children in preprimary school in

general health policies announced by the Supreme Leader (13).

B.2.2. Developing the policy document of the Fundamental Transformation of Educational System) (6). |

| B.3. Provide quality and compulsory primary and secondary education for all boys and girls, regardless of ability to pay and identify and address the barriers to girls and boys enrolling and staying in school. | B.3.1. Addressing the free primary and secondary education for all in the article 30 of the constitution. |

| B.4. Develop and implement economic and social policies that provide secure work and a living wage that takes into account the real and current cost of living for health. | |

| B.5. Build universal social protection systems and increase their generosity towards a level that is sufficient for healthy living. | B.5.1. Establishing universal basic health insurance scheme focusing on deprived social classes as a part of Health Transformation Plan (HTP) aiming to reduce catastrophic health expenditures (6). |

| B.6. Use targeting only as back up for those who slip through the net of universal systems. | |

| B.7. Ensure that social protection systems extend to include those who are in precarious work, including informal work and household or care work. |

B.7.1. Establishing a universal basic health insurance scheme focusing on those who are not

covered by any insurance schemes (including informal workers) as a part of Health Transformation

Plan (HTP) (6).

B.7.2 .Obligating the Ministry of Cooperation, Labor and Social Welfare to cover all the housewives in the social insurance scheme in the Sixth Development Plan of Iran (6). |

| B.8. Invest in expanding girls and women’s capabilities through investment in formal and vocational education and training. | B.8.1. Obligating the Deputy for Women Affair of the Iranian Presidential Organization to develop a comprehensive plan for empowering female-headed households in partnership with stakeholder organizations. |

| B.9. Support women in their economic roles by guaranteeing pay-equity by law, by ensuring equal opportunity for employment at all levels, and by setting up family-friendly policies that ensure women and men can take on care responsibilities in an equal manner. | |

| B.10. Research funding bodies create a dedicated budget for generation and global sharing of evidence on social determinants of health and health equity, including health equity intervention research. | B.10.1. Establishing SDH research centers in provincial universities of medical sciences throughout the country, each with their own budget line. |

| B.11. Educational institutions and relevant ministries make the social determinants of health a standard and compulsory part of training of medical and health professionals. |

B.11.1. Obligation of all universities of health and medical sciences to

pass a predesigned course on SDH for all faculty members in their annual

promotion as a criterion. 2. Holding a national workshop on “SDH: concepts and skills” for faculty members of all universities of health and medical sciences. |

| B.12. Educational institutions and relevant ministries act to increase understanding of the social determinants of health among non-medical professionals and the general public. |

B.12.1. Establishing Health Secretariats in more than 10 governmental organizations

outside the health system as a substructure of the SCHFS secretariat

toward realizing Health in All Policies Paradigm through constant

monitoring of policy contents and processes.

B.12.2. Planning to hold different national capacity building workshops for the representatives of non-health organizations, with the aim of informing them about their potential impacts on SDH, in association with WHO. B.12.3. Signing more than 10 intersectoral Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) for health between Ministry of Health and other non-health ministries (Energy, State, Education, Culture and Islamic Guidance, Cooperation Labor and Social Welfare, Industry Mining and Trade, and Economy) and organizations (Department of Environment, Institute of Standards and Industrial Research) as well as monitoring and evaluating the implementation of these MoU. |

| B.13. Reduce insecurity among people in precarious work arrangements including informal work, temporary work, and part-time work through policy and legislation to ensure that wages are based on the real cost of living, social security, and support for parents. | |

| B.14. Develop and implement economic and social policies that provide secure work and a living wage that takes into account the real and current cost of living for health. | |

| B.15. Build and strengthen national capacity for progressive taxation. | |

| B16. New national and global public finance mechanisms should be developed, including special health taxes and global tax options. |

B.16.1. Allocating 1% of VAT to HTP;

B.16.2. Obligation of the government to design a system to impose a tax on a list of predefined health-damaging goods (such as fatty products, cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages) announced annually by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education and spend the pooled funds on intersectoral joint projects for health promotion. |

| C) Intersectoral environmental interventions | |

| C.1. Manage urban development to ensure greater availability of affordable quality housing; invest in urban slum upgrading, including provision of water and sanitation, electricity, and paved streets for all. | |

| C.2. Plan and design urban areas to promote physical activity through investment in active transport; encourage healthy eating through retail planning to manage the availability of and access to food; and reduce violence and crime through good environmental design and regulatory controls. | |

| C.3. Develop and implement policies and programs that focus on issues of rural land tenure and rights, year-round rural job opportunities, agricultural development and fairness in international trade arrangements, rural infrastructure, including health, education, roads, and services; and policies that protect the health of rural-to-urban migrants. | |

| C.4. Occupational health and safety policy and programs should be applied to all workers – formal and informal – and the wage range should be expanded to include work-related stressors and behaviors as well as exposure to material hazards. | C.4.1. Developing related guidelines and policy documents on health safety by the Environmental and Occupational Health Center in the MOHME. |

| C.5. Strengthen public sector leadership in the provision of essential health-related goods/services and control health-damaging commodities. | C.5.1. In Iran, almost all primary health care services are provided by the public sector. Also, implementing the Health Transformation Plan (HTP) and subsequent changes in the paying system resulted in the shifting of both patients and health workforce from private to public sector (6). |

| C.6. Public capacity should be strengthened to implement regulatory mechanisms to promote and enforce fair employment and decent work standards for all workers. | |

HiAP: Health in All Policies, HTTP: Health Transformation Plan, MoHME: Ministry of Health and Medical Education, SCHFS: Supreme Council of Health and Food

Security, SDH: Social Determinants of Health, VAT: Value Added Tax, WHO: World Health Organization

Recommendations are categorized into 3 groups: (a) intersectoral governance interventions; (b) intersectoral socioeconomic interventions; and (c) intersectoral environmental interventions. As demonstrated in Table 1, some cells in the table are blank and, for some recommendations, corresponding interventions were not found, indicating that either no intervention was conducted by the health system, or the existing interventions are not documented properly. Apart from the high-level documents, such as the Constitution and National Development Plan, the interventions conducted by organizations outside the health system are not displayed in the table. Also, some of the examples mentioned in Table 1 had been implemented prior to HTP implementation.

For the first group (the intersectoral governance interventions), 14 out of 17 (82.3%) recommendations had a corresponding example in the country (Table 1). This implies that the relevant political or decision-making structure in the Iranian health system, which is responsible for the governance, has done well. However, many of the interventions still remain to be implemented. Moreover, continuity and sustainability of the policies and programs are still a concern. The corresponding examples for the intersectoral socioeconomic interventions were reduced to 10 out of 16 (62.5%), which indicates problems in policies and programs for resource allocation. A likely explanation is that managers and experts in executive bodies, who are responsible for resource allocation, do not see health as a top priority. Also, there is a lack in tangible, coherent, and national-level perspectives on this issue. In the last group (the environmental interventions), examples were found for only 2 out of 6 (33.3%) recommendations. This confirms that policymakers in the health system still do not pragmatically understand the importance of such issues as unemployment, proper housing, and rural development and their impact on health. It must be reemphasized that for this group of recommendations, examples could be found among the interventions conducted by organizations outside the health system. However, as the aim of this study was to assess the role of the health system and interventions, they were not mentioned in Table 1. A prominent example of these interventions is the “Mehr” mass housing scheme. This project was started in 2007 to provide affordable housing for low-income communities (18). However, there were many problems and shortcomings in the project, some of which were due to lack of health impact assessment.

Overall, these findings showed that the Iranian health sector and other executive bodies have taken some positive steps to strength health-oriented intersectoral actions. Moreover, the culture of cooperation and teamwork is developing in the country and if we were to prepare this table 4 years ago, there would have definitely been more blank cells. Nonetheless, there are still bureaucratic obstacles to establish official organizational cooperation in the country, which sometimes have led to isolated and disruptive interventions that did not have the opportunity to be integrated. Fortunately, high-level documents have largely tried to address this weakness by defining clear plans to achieve strategic health-related goals. Also, it is recommended to move the focus from issue-specific health topics (eg, tobacco, non-communicable diseases, climate change, air pollution) to systemic approaches (eg, Health in All Policies (HiAP) (19, 20).

Furthermore, monitoring these intersectoral actions is the key for decision-making. Although a list of indicators for evaluating health-oriented intersectoral actions were prepared (7), no reports have been published yet.

Some ministries, such as Ministry of State, have comprehensive roles in establishing intersectoral partnerships (21) owing to the existence of political party systems, Islamic Councils of Cities and Villages, NGOs, and monitoring the performance of the governors and governorates. Thus, Ministry of State can be considered as the entry point of the health system to develop intersectoral collaboration in the country.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Cite this article as: Riazi-Isfahani S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Mafimoradi Sh, Majdzadeh R. Universal health coverage in Iran: Health-related intersectoral actions. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2018 (28 Dec);32:132. https://doi.org/10.14196/mjiri.32.132

References

- 1. McKee M, Figueras J, Saltman RB. Health Systems, Health, Wealth And Societal Well-Being: Assessing The Case For Investing In Health Systems: Assessing the case for investing in health systems: McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2011.

- 2.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Organization WH. World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 4. Memaryan N, Rassouli M, Mehrabi M. Spirituality concept by health professionals in Iran: A qualitative study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Damari B, Vosoogh-Moghaddam A, Riazi-Isfahani S. Implementing Health Impact Assessment at National Level: An Experience in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(2):246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moradi-Lakeh M, Vosoogh-Moghaddam A. Health sector evolution plan in Iran; equity and sustainability concerns. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(10):637. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olyaeemanesh A, Behzadifar M, Mousavinejhad N, Behzadifar M, Heydarvand S, Azari S. et al. Iran’s Health System Transformation Plan: A SWOT analysis. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2018;32(1):224–30. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.32.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahmadnezhad E, Sajadi HS, Abdi Z, Ehsani-Chimeh E, Majdzadeh R. An overview of the health-system transformation plans toward Universal Health Coverage in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2019(under review).

- 9.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Health CoSDo. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pega F, Valentine NB, Rasanathan K, Hosseinpoor AR, Torgersen TP, Ramanathan V. et al. The need to monitor actions on the social determinants of health. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(11):784–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.184622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damari B, Shadpour K. Provincial Health Policy Secretariate: Coordinating and Brokering Structure for Comprehensive Health. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2014;11(4):15–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alikhani S, Damari B. A partnership model to improve population health screening for noncommunicable conditions and their common risk factors, Qazvin, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;22(12):904–9. doi: 10.26719/2016.22.12.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vosoogh-moghaddam A, Damari B, Alikhani S, Salarianzedeh M, Rostamigooran N, Delavari A. et al. Health in the 5th 5-years Development Plan of Iran: main challenges, general policies and strategies. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beheshtian M, Olyaeemanesh A, Bonakdar S, Malekafzali H, Larijani B, Hosseini L. et al. Intersectoral collaboration to develop health equity indicators in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aghababa S, Maleki M, Gohari M. Narrative review of studies on charity in health care, Iran. Hakim Res J. 2015;17(4):329–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghababa S, Nasiripour AA, Maleki M, Gohari M. Demographic characteristics of donors: an exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in health care of Iran. Curr Sci. 2015;109(9):1704. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rarani MA, Nosratabadi M, Moeeni M. Early childhood development in Iran and its provinces: Inequality versus average. The International journal of health planning and management. 2018;33(4):1136–45. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isalou AA, Litman T, Irandoost K, Shahmoradi B. Evaluation of the affordability level of state-sector housing built in Iran: case study of the Maskan-e-Mehr project in Zanjan City. J Urban Plan D Asce. 2014;141(4):05014024. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krech R, Valentine NB, Reinders LT, Albrecht D. Implications of the Adelaide statement on health in all policies. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:720. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.082461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lazzari A, De Waure C, Azzopardi-Muscat N. Health in all policies. A systematic review of key issues in public health: Springer; 2015. p. 277-86.

- 21.Pourkarimi E, Noroozi N, Ebtekar M. A Conceptual Model for Integrated Management of the Urban Environment in Tehran Metropolis (Based on the Good Governance Guidelines) Int J Environ Res. 2016;10(3):391–400. [Google Scholar]