Abstract

Post-transcriptional modification of RNA, the so-called ‘Epitranscriptome’, can regulate RNA structure, stability, localization, and function. Numerous modifications have been identified in virtually all classes of RNAs, including messenger RNAs (mRNAs), transfer RNAs (tRNAs), ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and other noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs). These modifications may occur internally (by base or sugar modifications) and include RNA methylation at different nucleotide positions, or by the addition of various nucleotides at the 3’-end of certain transcripts by a family of terminal nucleotidylyl transferases. Developing methods to specifically and accurately detect and map these modifications is essential for understanding the molecular function(s) of individual RNA modifications and also for identifying and characterizing the proteins that may read, write, or erase them. Here, we focus on the characterization of RNA species targeted by 3’ terminal uridylyl transferases (TUTases) (TUT4/7, also known as Zcchc11/6) and a 3’−5’ exoribonuclease, Dis3l2, in the recently identified Dis3l2-mediated decay (DMD) pathway - a dedicated quality control pathway for a subset of ncRNAs. We describe the detailed methods used to precisely identify 3’-end modifications at nucleotide level resolution with a particular focus on the U1 and U2 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) components of the Spliceosome. These tools can be applied to investigate any RNA of interest and should facilitate studies aimed at elucidating the functional relevance of 3’-end modifications.

Keywords: DIS3L2, U1, U2, TUTase, 3’-end Uridylation, snRNA, DIS3L2-Mediated Decay (DMD)

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview and background

Regulation of RNA biogenesis and decay is critical for normal gene expression while dysregulation of the RNA life cycle is associated with a variety of human disorders1–5. Whereas transcriptional regulation of RNA expression has been widely studied, the importance of RNA decay is only beginning to be appreciated6–14. More specifically, studying the regulation of noncoding RNA (ncRNA) expression and decay is hampered due to limitations caused by their size, abundance, modification, and/or structural complexities. Major advances in high throughput sequencing methods combined with biochemical approaches have enabled researchers to begin to unravel the significance of such ncRNA biogenesis and decay. RNA-protein interactions are the core of many molecular machineries in the cells: most of the ncRNAs function through participation in ribonucleoprotein complexes consisting of the RNA and protein subunit(s); several RNA-modifying enzymes add, remove, or modify nucleotides or bases to adjust, fine-tune, or abolish RNA function or abundance. Of particular relevance, exoribonucleases play a major role in the turnover of mRNAs and ncRNAs, ensuring the dynamic regulation of the RNA life cycle. Impaired activity of exoribonucleases entails accumulation of RNA species that are no longer required by the cell and may have pathological consequences.

Dis3l2, for example, is a 3’−5’ exoribonuclease that is involved in the quality control of ncRNAs15–23. Germline mutations of human DIS3L2 have been linked to pediatric Perlman syndrome overgrowth and hypersusceptibility to renal Wilms tumor22. Several studies have identified different ncRNAs as the targets of Dis3l2 exoribonuclease activity. An oligonucleotide tail comprising a stretch of >12–14 uridines is added post-transcriptionally to the 3’-end of the Dis3l2 targets by the two Terminal Uridyl Transferase (TUTase) enzymes, TUT4 (Zcchc11) and TUT7 (Zcchc6)15,24–26. This 3’-end U-tail marks RNAs for recognition by Dis3l2 and triggers Dis3l2 exoribonuclease activity. Therefore, both identification of Dis3l2 targets and characterization of their 3’-end sequences are critical to understand the molecular and biological function of Dis3l2.

1.2. Limitations of existing approaches

A wide variety of CLIP (cross-linking immunoprecipitation) methods have been developed to simultaneously determine the repertoire of protein-bound RNA species and their binding sites at nucleotide resolution27–32. However, in general, CLIP methods are not highly suitable for studying exoribonuclease enzymes functioning on RNA tails because: (a) exoribonucleases commonly bind to a stretch of low-complexity oligonucleotides consisting of A-tails or U-tails, so using CLIP methods will likely not expand our understanding of their binding sites; (b) CLIP methods usually rely on short cDNA sequence reads corresponding to fragments of RNA species, so having relatively long A- or U-tails already at the 3’-end of the exoribonuclease target RNAs will only leave a short length of target RNA that could be used for alignment to the genome.

Moreover, while genome-wide sequencing of mRNA tails has successfully revealed global 3’end modifications, this approach might overlook tail modifications of an individual RNA species with lower frequencies and/or abundance33. Therefore, development of an in-depth single transcript-based sequencing method is required to study the tail composition. Besides, compared to mRNAs, ncRNAs might be refractory to 3’-end ligation due to their more complex secondary or tertiary structures. Thus, each tail-sequencing step needs to be optimized on a case-by-case manner for any single transcript. To overcome these limitations, we propose combining RNA immunoprecipitation34 of Dis3l2-bound transcripts with two alternative tail sequencing approaches, cRACE (Rapid amplification of cDNA ends from circular RNAs)35–37 and 3’-ligation RACE. This enables one to (a) enrich for Dis3l2-bound uridylated RNA species, and (b) to perform in-depth gene-specific analysis of Dis3l2-targeted end sequences.

2. Protocol

2.1. ESC culture and transfection

Feeder-free TC1 mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) were cultured on 0.2% gelatin (Sigma #G1890)-coated dishes in LIF/Serum medium containing knockout-DMEM (Gibco #10829–018), 1000 units/ml mouse recombinant LIF (Gemini #400–495), 15% Embryonic Stem Cell Qualified FBS (Gemini #100–125), 2 mM HEPES (Gibco #15630–080), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Gibco #11360–070), 1X NEAA (Gibco #11140–050), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco #25030–081), 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Acros Organics #125470010) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco #15140–122), as previously described38. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was used to delete exon 3 of the Dis3l2 locus and resulted in Dis3l2 protein loss of function that in turn caused an accumulation of the Dis3l2 targets in knockout ESCs18. For each IP experiment, on 15-cm gelatin-coated dishes, 107 Dis3l2 knockout ESCs were transiently transfected overnight with transfection complexes containing 10 μg FLAG-tagged mutant Dis3l2 (D389N) expression vector and 30 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen #52887) prepared in 3 ml OptiMEM medium (Invitrogen #31985–070). The catalytic mutant Dis3l2 protein was shown to bind to target RNAs but lacks the exoribonuclease activity15. We routinely perform reverse-transfection to maximize introduction of expression plasmids into ESCs. The day after transfection, the media was changed with fresh LIF/Serum medium to avoid toxic effects of Lipofectamine. We recommend a parallel transfection of the cells with a fluorescent protein (e.g. pMax-GFP, Lonza #PBP3–02250), or western blot analysis of the protein of interest to monitor expression and accumulation of expressed plasmids. In our experience, 48h after transfection, the expression of FLAG-mutant Dis3l2 protein is sufficient for the immunoprecipitation experiment.

2.2. RNA immunoprecipitation

We commonly UV-crosslink protein-RNA complexes to stabilize their interaction. However, immunoprecipitation of native complexes (without UV-crosslinking) may have only a minimal negative influence on RNA enrichment (data not show). Transfected mESCs were washed twice with cold PBS (Invitrogen #14190–144) to remove dead cells and residual media. 5 ml cold PBS was added to the 15-cm dishes to cover the mESC cultures and then UV-crosslinked using Spectrolinker XL-1000 (Thomas Scientific) at 4 J/cm2 energy. PBS was aspirated completely and cells were immediately stored at −80 °C or continued to RIP by lysing in 1 ml lysis buffer [20 mM Tris HCl (pH~8), 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM 0.5M EDTA, 1% Triton X100, 10% Glycerol and 1.5 mM MgCl2, supplemented with 20 μl RNaseOUT (Invitrogen #10777–019) and 20 μl Complete Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Roche #11873580001)] for each 15-cm dishes on ice. Cells were scraped and lysates were collected into 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes, centrifuged at 4 °C at 12000 G for 5 minutes, and the supernatant lysates were transferred into fresh tubes. To eliminate DNA contamination, DNase treatment was performed on lysates by adding 10 μl RQ1 DNase (Promega #M610A) and incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C. Meanwhile, for each IP reaction, 40–60 μl anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel beads slurry (Sigma #A2220) were washed twice in cold lysis buffer. We perform these steps as a master mix, in which we combine beads needed for all the reactions, and at the last washing step we aliquot the beads into appropriate number of tubes corresponding to each IP reaction. All the centrifugation steps were performed at 4 °C at 3000 G for 3 minutes. After DNase I treatment, lysates were directly added to washed M2 beads and incubated for 2–4 hours at 4 °C in rotation. Next, beads were collected by centrifugation and the remaining lysates were decanted. Beads were washed 3–5 times (each for 3 minutes at 4 °C in rotation) with cold RIP wash buffer (1x PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% NP-40), and then 3–5 times (each for 3 minutes at room temperature in rotation) with high salt RIP wash buffer (5x PBS, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% NP-40). After the last washing step, 150 μl lysis buffer was added to beads containing FLAG-Dis3l2 and copurified RNAs, supplemented with 100 μg Proteinase K (Ambion # AM2546), and incubated at 45 °C for 45 minutes (or at 37 °C for 3 hours) for protein digestion. Next, RNA was extracted using Trizol (Ambion # 15596026) RNA extraction protocol. During precipitation with isopropanol, we recommend overnight incubation to maximize RNA precipitation and also using Glycogen (1 μl; Illumina #15073058) for better visualization of RNA pellets. Centrifugation for 20–30 minutes at 4 °C, at 12000G would also ensure a higher yield of precipitated RNAs. Finally, RNA pellets were dissolved in 15 μl dH2O and stored at −80 °C or proceeded with RNA circularization (cRACE)/3’-ligation RACE steps.

2.3. cRACE

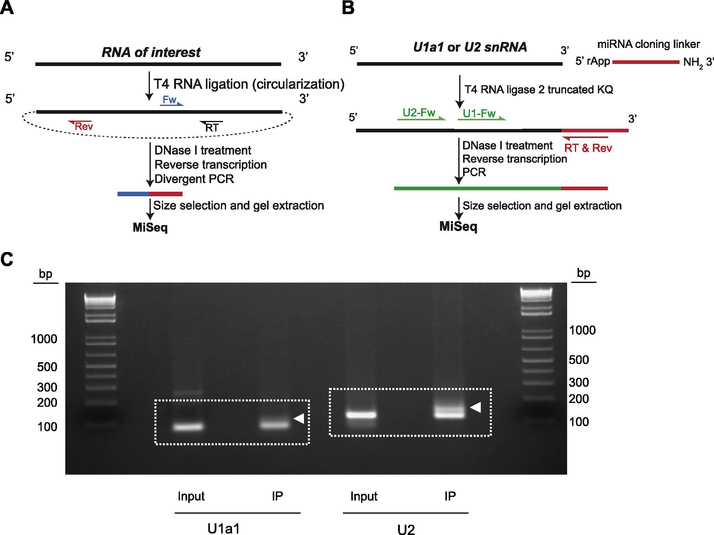

RNA circularization, when combined with divergent PCR reaction, can capture the sequence information from both 3’- and 5’-ends of an individual RNA transcript. Efficient intramolecular ligation may depend on the end modification and/or structures in solutions. Previously, we established cRACE analysis of Rmrp as a main target of Dis3l218. Here, we describe the detailed protocol for Rmrp cRACE (Figure 1A):

Figure 1.

cRACE and 3?-ligation protocols. Schematic representation of cRACE (A) and 3?-ligation RACE (B) methods are shown. (C) Ethidium bromide staining of PCR products for U1 and U2 snRNAs (3?-ligation RACE) run on 1% agarose gel. Dashed rectangles represent the regions that were cut and used for DNA extraction from the gel. White arrowheads point to elongated slow-migrating PCR product accumulated especially in IP samples.

2.3.1. T4 RNA ligation:

10X RNA ligase buffer (NEB #B0216), 2 μl

10 mM ATP, 1 μl

50% PEG 8000 (NEB #B1004), 4 μl

100–300 ng Dis3l2-bound RNA (IP) or 2 μg input RNA, in 12 μl

T4 RNA ligase 1 (NEB #M0204), 1 μl

The total reaction mix (20 μl) was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature and then the ligase was inactivated by boiling samples for 5 minutes at 95 °C.

2.3.2. Reverse transcription step:

The circularized RNAs from input and IP samples were then used in a reverse transcription (RT) reaction by SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen #18080–093) as:

Circularized RNA, 11 μl

10 mM dNTP mix, 1 μl

50 μM Gene-specific RT primer, 1 μl

5X First-Strand Buffer, 4 μl

0.1 M DTT, 1 μl

RNaseOUT™ Recombinant RNase Inhibitor (Invitrogen #10777–019), 1 μl of 40 units/μl

SuperScript™ III RT (200 units/μl), 1 μl

Designing an appropriate RT primer is critical in this step because it enriches for the gene of interest and therefore should be highly specific. In the next step, using a reverse primer and another gene-specific forward primer, divergent PCR was set up to capture both the 3’- and 5’-ends of the transcript as well as the potential tails at each sides (Figure 1A). Because the majority of the Dis3l2-targeted transcripts are encoded by RNA Pol III and/or contain GC-rich regions, we used AccuPrime™ GC-Rich DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, #55904) and set up the PCR reaction as:

2.3.3. Divergent PCR amplification:

cDNA from RT step, 2 μl

5X Buffer A (Invitrogen, #55900), 5 μl

AccuPrime™ GC-Rich DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, #55904), 1 μl

10 μM Gene-specific Forward primer, 1 μl

10 μM Gene-specific Reverse primer, 1 μl

dH2O, up to 25 μl

PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel for size selection corresponding to the desired length of the products and then purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, # 28704). Running PCR products on the gel is highly recommended to check the specificity of the PCR reaction as well as to obtain a more selected PCR band for library preparation. Occasionally, after PCR amplification of the circularized RNA-derived cDNAs, we observe ladder-shape PCR product bands on the gel that may be derived from over-through cDNA synthesis of the circular RNAs. Optimization of the cDNA synthesis step as well as cutting the right band on the gel is essential to obtain appropriate PCR products for library preparation and sequencing.

2.4. 3’-ligation RACE

In our experience, however, not all Dis3l2 substrate RNAs can be circularized. This is most likely because of their 3’-end modifications or simply because of the greater distance between their 3’- and 5’-ends that could not be ligated intramolecularly. Therefore, to analyze the 3’-end identity of Dis3l2 targets, we established 3’-ligation RACE protocol (Figure 1B):

2.4.1. 3’-ligation

2 μg input RNA and 300 ng of Dis3l2-bound RNA (after RIP) were used for 3’-ligation reaction. Using less than 100 ng IP RNA will dramatically reduce the library complexity and results in low sequencing depth. We used T4 RNA Ligase 2, truncated KQ enzyme from NEB that does not require ATP but specifically ligates the pre-adenylated 5´-end of the Universal miRNA cloning linker to the 3´OH end of RNA. Moreover, because the 3´-end of this linker is blocked (–NH2-3´) concatenation of the RNAs was inhibited39. The 3’-ligation reaction consisted of:

10X ligation buffer (NEB #M0373), 4 μl

T4 RNA Ligase 2, truncated KQ (NEB #M0373), 3 μl

50% PEG 8000 (NEB #B1004), 10 μl

2 μM Universal miRNA cloning linker (5´-rAppCTGTAGGCACCATCAAT–NH2-3´) (NEB #S1315), 4 μl

RNaseOUT (Invitrogen #10777–019), 2 μl

RNA, 2 μg (input) or 300 ng (IP)

dH2O, up to 40 μl

Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 2–4 hours. RNA was purified using RNA Clean & Concentrator™-5 (Zymo Research #R1016) and eluted in 13 μl dH2O to recover 11 μl of RNA for the RT step.

2.4.2. Reverse transcription step:

3’-ligated RNA was then used in the RT reaction by SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen #18080–093) as:

3’-end ligated RNA, 11 μl

10 mM dNTP mix, 1 μl

50 μM Universal RT+Linker primer (CTACGTAACGATTGATGGTGCCTACAG), 1 μl

5X First-Strand Buffer, 4 μl

0.1 M DTT, 1 μl

RNaseOUT™ Recombinant RNase Inhibitor (Invitrogen #10777–019), 1 μl of 40 units/μl

SuperScript™ III RT (200 units/μl), 1 μl

2.4.3. PCR amplification

To amplify cDNA for sequencing library preparation, and to enrich for the tail of the gene of interest, we used PCR reactions using Universal RT and Linker primer and gene-specific forward primers:

1:3 diluted cDNA, 2 μl

10 μM Universal RT and Linker primer (CTACGTAACGATTGATGGTGCCTACAG), 1 μl

5X Buffer A (Invitrogen, #55900), 5 μl

AccuPrime™ GC-Rich DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, #55904), 1 μl

-

10 μM gene-specific forward primer, 1 μl

U1a1-Forward: GCATAATTTGTGGTAGTGGGGG

U2-Forward: TTGGAAGTAGGAGTTGGAATAGG

The annealing temperature and the number of PCR cycles depend on the gene of interest and the primers used. In principal, the lower number of PCR cycles and the higher annealing temperature, if possible, is recommended to decrease over-representation of individual transcripts and to increase PCR product specificity, respectively. PCR products are then run on 1% agarose gels and the corresponding amplicon was cut from the gel (Figure 1C). DNA products were recovered using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, # 28704). Similar to cRACE, examining PCR products on the agarose gel is highly recommended to check the specificity of the PCR reaction as well as to obtain a more selected PCR band for library preparation. Overall, we usually observe a slight increase in the size of the PCR product from IP samples compared to their corresponding inputs, suggesting the enrichment of the tailed/uridylated RNAs by Dis3l2. We recommend cutting the gels from the size of desired PCR product ±100 nt regions on the gel to ensure recovery of the truncated and longer products that might be overlooked on the gel (Figure 1C).

2.5. Library preparation and sequencing

Gel-extracted purified PCR products were further subjected to library preparation using TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 (Illumina, # RS-122–2001). Because the Illumina library preparation protocol uses mRNAs as the starting material we skip the RNA fragmentation and first and second strand cDNA synthesis steps and resume the protocol at 3’-end adenylation and continue to adapter ligation, PCR amplification and library purification. Alternatively, sequencing libraries can be prepared using first Taq DNA Polymerase (NEB, #M0267) for A-tailing and then Blunt/TA Ligase Master Mix (NEB, #M0367) for adapter ligation step before PCR amplification. Libraries were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq Sequencing 150 bp Paired End (PE150).

2.6. Bioinformatics analysis (TailSeq R Statistical Package)

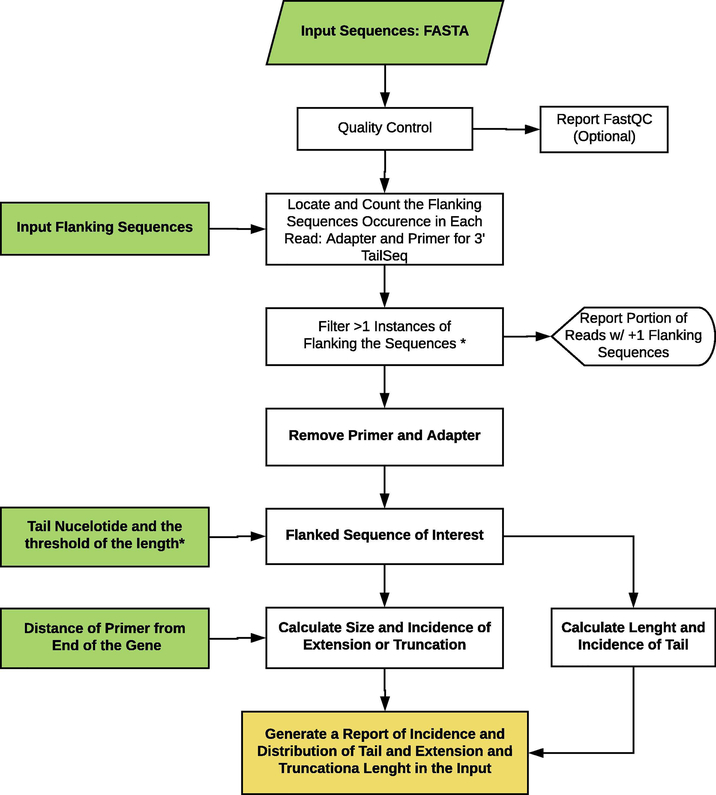

Although current packages like Biostrings that analyze sequence-based RNA or DNA sequences are very useful in many of applications, in our experience, they fail to capture the specific 3’-end sequence analysis up to the details we expected. To address this issue, we developed an R package called TailSeq to find the region of interest between the forward and reverse primers used for amplification of RNA tails, depending on the type of experiment used (cRACE or 3’-ligation RACE). First, we dissected the region of interest, which is located after the forward primer and before the adapter (3’-ligation RACE) or reverse primer (cRACE). Next, the TailSeq function eliminates the reads that contain more than one primer or adapter and extracts “normal reads” for further downstream analysis. Normal reads are those starting with the forward primers and terminating with the adapter (3’ligation RACE) or reverse primer (cRACE) sequences. Next, primer and adapter sequences are removed to generate “Flanked Sequence of Interest” that contains the sequence of the transcript after the forward primer up to the end of the transcript, followed by potential genomic extension (genomically encoded nucleotides extending past the normal 3’-end, hereafter referred as “genomic extension”), and/or U-tails. The TailSeq function asks the users to provide information about the length of the transcript after the forward primer that will be used to calculate the length of transcript’s truncation/ genomic extension. Moreover, the user needs to provide the nucleotide of interest for the tail (in our study, U-tail) and the threshold of the tail (depending on the gene, we considered >4 or >5 continuous Us as U-tail). Based on the information provided by the user, the TailSeq function will count the length and the frequencies of the genomic extension (or truncation) and the length and frequencies of the Utail (or any nucleotide and pattern of interest) and generate the csv report files as well as pie charts representing the number of “normal reads” and other information. The output reports can be used for troubleshooting and investigating the specific reads with a certain length of genomic extension or tail. Alternatively, the sequences can be used for any other downstream analysis. The flowchart of the TailSeq function is depicted in Figure 2. The TailSeq function can be called in R (the package is under review by CRAN; source (https://raw.githubusercontent.com/arefoddin/TailSeq/master/R/TailSeq.R). The detailed code of the TailSeq is as follows:

cRACE NOTE: For cRACE experiments, use the Rev Primer Sequence instead of the Adapter Sequence.

library(pbapply)

library(stringr)

library(zonator)

TailSeq <- function(file_path, primerSeq, adaptorSeq, distPrimerFromEoG,

tailNucleotide, tailThreshold) {

dat <- read.table(file_path, header = F, fill = T)

colnames(dat) <- “OriginalSequence”

dat$OriginalSequence <- as.character(dat$OriginalSequence)

primerSeq <- primerSeq

adaptorSeq <- adaptorSeq

pbapply::pboptions(type = “timer”, char = “=“)

cat(“Calculate Primer Incidence and Locations”)

dat$NumberOfPrimer <- pbapply::pbsapply(dat$OriginalSequence, function(x) dim(as.data.frame(stringr::str_locate_all(x, primerSeq)))[1])

cat(“Calculate Adaptor Incidence and Locations”)

dat$NumberOfAdaptor <- pbapply::pbsapply(dat$OriginalSequence, function(x) dim(as.data.frame(stringr::str_locate_all(x, adaptorSeq)))[1])

dat$NormalReads <- (dat$NumberOfPrimer == 1) == TRUE & (dat$NumberOfAdaptor == 1) == TRUE

pdf(paste0(zonator::file_path_sans_ext(file_path), “.pdf”, collapse = ““), onefile = T)

pie(table(dat$NumberOfAdaptor), main = “Number of Adaptor per reads”)

pie(table(dat$NumberOfPrimer), main = “Number of Primer per read”)

pie(table(dat$NormalReads), labels = 2, main = “Number of Good Reads”) dev.off()

cat(c(“Number of Adaptor per Read: “, table(dat$NumberOfAdaptor), “\n”))

cat(c(“Number of Primer per Read: “, table(dat$NumberOfPrimer), “\n”))

cat(c(“Number of Normal Reads: “, table(dat$NormalReads), “\n”))

dat_normal <- dat[dat$NormalReads, ]

cat(“\n”)

cat(paste0(c(“Number of Reads Excluded Due to Multiple Adaptor or Primer”, dim(dat)[1] - dim(dat_normal)[1]), collapse = “ : “))

dat_normal$end_of_primer <- pbapply::pbsapply(dat_normal$OriginalSequence, function(x) stringr::str_locate_all(x, primerSeq)[[1]][2])

dat_normal$start_of_adaptor <- pbapply::pbsapply(dat_normal$OriginalSequence, function(x) stringr::str_locate_all(x, paste0(adaptorSeq, “.*”, collapse = ““))[[1]][1])

flank <- function(string, eOFp, sOFa) { stringr::str_sub(string = string, start = eOFp, end = sOFa)

}

dat_normal$flank <- base::mapply(flank, dat_normal$OriginalSequence, dat_normal$end_of_primer + 1, dat_normal$start_of_adaptor - 1)

tailPattern <- paste0(c(rep(tailNucleotide, tailThreshold), “.*”), collapse = ““)

dat_normal$woTail <- gsub(tailPattern, ““, dat_normal$flank)

dat_normal$sizeOfTail <- nchar(dat_normal$flank) - nchar(dat_normal$woTail)

dat_normal$sizeofExt <- nchar(dat_normal$woTail) - distPrimerFromEoG

write.csv(dat_normal, paste0(file_path_sans_ext(file_path), “processed_TailSeqv2.csv”, collapse = ““))

write.csv(table(dat_normal$sizeofExt), paste0(file_path_sans_ext(file_path), “SizeOfExt_processed_TailSeqv2.csv”, collapse = ““))

write.csv(table(dat_normal$sizeOfTail), paste0(file_path_sans_ext(file_path), “SizeOfTail_processed_TailSeqv2.csv”, collapse = ““))

return(dat_normal)

}

Running U1 and U2 3’-ligation RACE Libraries

Note: To calculate the length of truncations or genomic extensions, the distance of the End of the Gene from End of the Fw Primer needs to be provided by the user (22nt for U1, and 62nt for U2).

Note: For cRACE experiments, this number will be the sum of the distances of Rev Primer from the 5’end and the Fw Primer from the 3’-end.

TailSeq(file_path = “a5.fasta”,

primerSeq = “GCATAATTTGTGGTAGTGGGGG”,

adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

distPrimerFromEoG = 22,

tailNucleotide = “T”,

tailThreshold = 4)

TailSeq(file_path = “a6.fasta”,

primerSeq = “GCATAATTTGTGGTAGTGGGGG”,

adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

distPrimerFromEoG = 62,

tailNucleotide = “T”,

tailThreshold = 4)

TailSeq(file_path = “a7.fasta”,

primerSeq = “TTGGAAGTAGGAGTTGGAATAGG”,

adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

distPrimerFromEoG = 62,

tailNucleotide = “T”,

tailThreshold = 4)

TailSeq(file_path = “a8.fasta”,

primerSeq = “TTGGAAGTAGGAGTTGGAATAGG”,

adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

distPrimerFromEoG = 62,

tailNucleotide = “T”,

tailThreshold = 4)

> TailSeq(file_path = “a5.fasta”,

+ primerSeq = “GCATAATTTGTGGTAGTGGGGG”,

+ adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

+ distPrimerFromEoG = 22,

+ tailNucleotide = “T”,

+ tailThreshold = 4)

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 55s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 55s

Number of Adaptor per Read: 333490 9362

Number of Primer per Read: 334381 8471

Number of Normal Reads: 9628 333224

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 09s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 10s

>

> TailSeq(file_path = “a6.fasta”,

+ primerSeq = “GCATAATTTGTGGTAGTGGGGG”,

+ adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

+ distPrimerFromEoG = 22,

+ tailNucleotide = “T”,

+ tailThreshold = 4)

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 01m 03s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 01m 02s

Number of Adaptor per Read: 365819 14474

Number of Primer per Read: 367414 12879

Number of Normal Reads: 14776 365517

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 10s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 11s

>

> TailSeq(file_path = “a7.fasta”,

+ primerSeq = “TTGGAAGTAGGAGTTGGAATAGG”,

+ adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

+ distPrimerFromEoG = 62,

+ tailNucleotide = “T”,

+ tailThreshold = 4)

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 35s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 35s

Number of Adaptor per Read: 210065 177

Number of Primer per Read: 210141 101

Number of Normal Reads: 238 210004

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 06s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 06s

>

> TailSeq(file_path = “a8.fasta”,

+ primerSeq = “TTGGAAGTAGGAGTTGGAATAGG”,

+ adaptorSeq = “CTGTAG”,

+ distPrimerFromEoG = 62,

+ tailNucleotide = “T”,

+ tailThreshold = 4)

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 32s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 32s

Number of Adaptor per Read: 192343 65

Number of Primer per Read: 192397 11

Number of Normal Reads: 68 192340

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 05s

|==================================================| 100% elapsed = 06s

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the TailSeq function.

3. Results

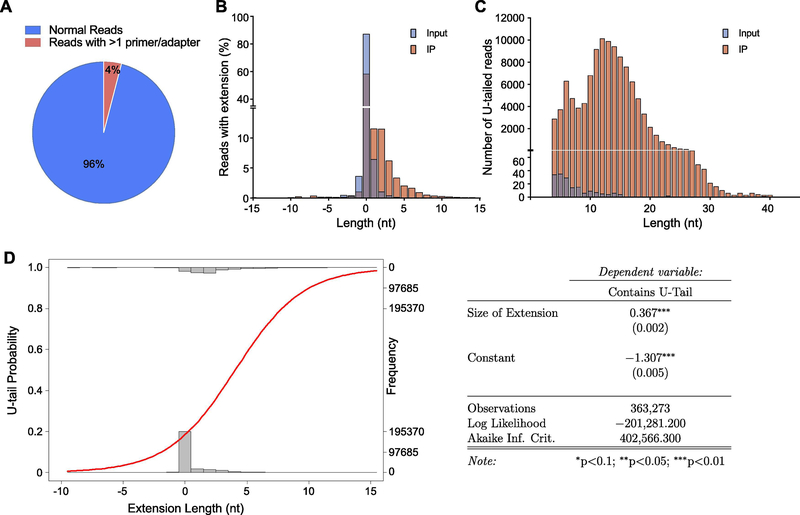

Bioinformatic analysis of MiSeq data for U1 and U2 transcripts showed specific amplification of their 3’-ends. A small fraction of the sequencing reads contained more than one primer or adapter in each read (Figure 3A, 4A). This is particularly important because although the 3’-end of the adapter was blocked, we still observed some reads that contained more than one adapter. In our experience, increased concentration of the adapter or primer used may cause this concatenation, However, our bioinformatic tool eliminates these reads from further analysis (see above). Another explanation for a decreased number of reads with more that one adapter and one primer, especially in U2-related samples, is due to a longer amplicon in U2 cDNA PCR that minimize the chance of sequencing for reads with multiple primers/adapter. Analysis of U1 RNA 3’-end in input sample showed that the majority of these RNAs end accurately at the annotated 3’-end (more that 80% of the reads having 0 nucleotide genomic extension). However, this number was decreased in Dis3l2-bound IP samples, as only 60% of the reads had no genomic extension, and instead, the rest contained up to 10 nucleotides genomic extensions at their 3’-ends (Figure 3B). This is in line with the quality control role of Dis3l2 in the elimination of the extended/aberrant RNA species16,18,40. Bioinformatic analysis of U-tails showed a widespread 3’-end uridylation of U1 RNAs especially in IP samples (Figure 3C). This further confirms the molecular requirement of Dis3l2 binding to a RNA molecule containing a long U-tail at their 3- end15,18,41. Most of the uridylated RNAs contained around 12 nucleotides of Us, which is in line with previous molecular15 and structural studies41. Our approach also enabled us to further analyze the uridylation frequencies among RNA species in relation to their 3’-ends genomic extension. Logistic regression analysis revealed that the increased level of genomic extension in U1 3’-end dramatically increases the probability of 3’-end uridylation (Figure 3D). This clearly proves that inaccurate transcription termination in the 3’-end of the U1 RNA induces the RNA uridylation that further triggers RNA-binding to Dis3l2.

Figure 3.

3?-ligation analysis of Dis3l2-bound U1 snRNA. (A) Pie chart representing the percentage of the sequencing reads containing only 1 primer and 1 adapter. Only 4 percent of the total reads contained more than 1 primer of adapter. (B) Bar diagram representing the percentage of the reads in input and Dis3l2-IP with indicated genomic extension (plus numbers), truncation (minus numbers), or annotated ends (zero). (C) Bar diagram showing the number of reads in input and Dis3l2-IP with indicated length of U-tails. (D) Logistical regression of U-tail existence depending on the length of the genomic extension and the respective probabilities (right panel).

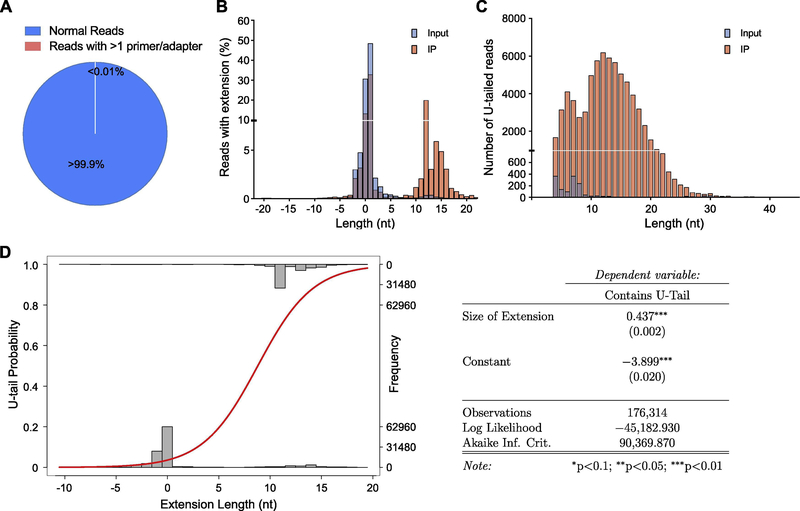

Figure 4.

3?-ligation analysis of Dis3l2-bound U2 snRNA. (A) Pie chart representing the percentage of the sequencing reads containing only 1 primer and 1 adapter. Note the negligible portion of the reads with more than 1 primer or adapter. (B) Bar diagram representing the percentage of the reads in input and Dis3l2-IP with indicated genomic extension (plus numbers), truncation (minus numbers), or annotated ends (zero). Note the increased extended reads especially in the IP sample. (C) Distribution of the sequencing reads in input and Dis3l2-IP with indicated length of U-tails. (D) Logistical regression of U-tail existence depending on the length of the genomic extension and the respective probabilities (right panel).

Similar results were observed in analysis of U2 snRNAs bound to Dis3l2. The only difference was that Dis3l2 preferentially bound to U2 RNA species with longer 3’-end genomic extensions (with 10–20 nucleotides, with a peak of 12 nucleotides) (Figure 4B). Furthermore, Dis3l2 IP enriched for uridylated U2 RNAs with up to 30 nucleotides of U (with a peak of 10–15) (Figure 4C). Again, increased 3’-end genomic extension at 3’-ends increased the probability of being uridylated (Figure 4D) further proving that Dis3l2-mediated decay (DMD) is a common mechanism to eliminate inaccurately terminated RNA species. Interestingly, TUT7-mediated uridylation and degradation of truncated U1 and U2 has been reported to be differentially involved during biogenesis steps of these snRNA, though Dis3l2 was reported to be dispensable for steady-state level of U1 and U2 snRNAs42, further suggesting a quality control role of Dis3l218.

4. Hints for troubleshooting and further notes

Low RNA yield after RIP –

This might be caused by inefficient IP or inefficient RNA recovery from the beads. To increase the RNA yield, one may start with an increased number of cells for RIP, an increased amount of FLAG-beads, or overnight incubation of beads with lysates. We suggest using a minimum of 100 ng IP RNA for Illumina library preparation. Increased number of PCR cycles is not recommended as it may cause over-representation of abundant RNAs and end up with low complexity and low coverage libraries. We observe a minimal improvement of the Dis3l2-bound RNA recovery with UV-crosslinking. However, it may help efficient recruitment of other protein-RNA complexes. It is always recommended to check the expression of the protein of interest in the lysates by western blotting prior to IP experiments, especially if transient transfection is used to ectopically express FLAG-tagged protein.

Unspecific enrichment of RNAs –

We always compare IP RNAs with input RNAs to measure enrichment and only consider highly enriched RNAs (>10-fold) as bona fide Dis3l2-bound RNAs to start further characterizations. However, to rule out the unspecific binding of the RNAs to the beads, one may also include anti-FLAG IP of the mock transfected cells (with empty pFLAG-CMV2 or similar vectors). Ideally, authentic Dis3l2-bound RNAs should not be enriched after FLAG-IP of the mock-transfected cell lysates. Alternatively, to eliminate unspecific binding of RNAs to the beads, lysates can be precleared with IgG-bound agarose beads prior to IP.

Inefficient detection of tailed RNAs after sequencing –

We recommend performing low cost and rapid Sanger sequencing using different conditions for ligation, PCR, primer sets, etc. to evaluate the efficiencies of different procedures and/or the specificity of the primers used before proceeding to MiSeq. In this case, because AccuPrime™ GC-Rich DNA Polymerase generated blunt ends, after PCR amplification, PCR products should be further incubated with 1 μl Taq polymerase for 20 minutes at 72 °C to add an A-overhang and to prepare the PCR product for cloning into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega #A1360) and further bacterial transformation, miniprep and Sanger sequencing. 3’-end dephosphorylation of RNAs may also help efficient ligation43.

Further remarks for bioinformatics analysis -

Because most of the analyzed Dis3l2-targeted transcripts are Pol III transcribed genes, and they typically end with a track of oligo-T patches at their 3’-end flanking region44,45, it is challenging to distinguish the actual U-tails at the 3’-end of the transcripts from the genomic encoded extensions and to assess the actual length of the U-tail. We compromised this by increasing the minimal length of Us required to be considered as U-tail (i. e. “tailThreshold”), sometimes up to 5 continuous patches of Us.

Occasionally, we observe that U-tails are interspersed with other nucleotides, A, C, or G. We cannot distinguish whether these non-U tails are actually added post-transcriptionally in cells or are just simply reflecting sequencing errors. Our bioinformatics analysis considers this possibility and allows mismatches to still be considered as U-tail.

Although the adapter used for the 3’-ligation step is blocked in its 3’-end, increased concentration of the adapter, in our experience, will cause concatenation and makes the analysis of the genomic extension and U-tail length more challenging. Sanger sequencing of small-scale experiments with different concentrations of the primer and adapter can help optimize the ligation/PCR conditions.

Location of the designed primer is important to recover as much extension and truncation as possible because the total read length in MiSeq analysis is 150 nucleotides, consisting of the primer, adapter, U tail, and genomic extension altogether.

5. Conclusion remarks

Previously, we utilized RNA immunoprecipitation34 followed by high throughput sequencing to identify Dis3l2-targeted transcripts. Moreover, we used RNA sequencing to identify the sequence and the distribution of U-tails and 3’-end genomic extension or truncation of Dis3l2 targets. Here, we presented the detailed methods of assessing end modifications at both 5’- and especially 3’-ends of noncoding RNAs that are targeted by Dis3l2. The robustness and simplicity of these cRACE and 3’-end ligation RACE methods make them suitable for a variety of different highly structured noncoding RNAs. So far we have applied these methods to long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) Rmrp, 7SL, U1, and U2 snRNAs as well as ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) (data not shown). It is noteworthy that compared to other available CLIP-Seq or Tail-Seq approaches, our methods provide more in-depth understanding of the RNA ends and has enabled us to assess detailed identity of noncoding RNA ends through first, enrichment using Dis3l2-immunoprecipitation, and second, by using gene-specific amplifications. However, our methods lack genome-wide coverage and needs to be set-up separately for any individual interested target RNA. Particularly, in our experience, some RNA species are more efficiently circularized and could be used for cRACE analysis while for snRNAs, for example, only 3’-ligation RACE is applicable. This further suggests for individual RNA-centric approaches like what we proposed here. Finally, our methods can be adapted to other RNA-binding proteins and/or exonucleases, for example the RNA exosome (data not shown), etc. that function in the 5’- or 3’-end maturation or processing steps of the RNA life.

6. Highlights.

Detailed biochemical and bioinformatics analyses of Dis3l2-bound RNAs are provided.

Dis3l2 majorly binds to 3’-end truncated or elongated RNA species of U1 and U2 snRNAs.

Dis3l2 RIP enriches for highly uridylated RNA transcripts.

3’-end truncation or elongation dramatically increases the probability of RNA target uridylation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carmen Rios for helpful comments on the text. This work was supported by grants to R.I.G. from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH-NIGMS) (R01GM086386), US National Cancer Institute (NCI) (R01CA211328), and the March of Dimes Foundation (FY15–3339) and postdoctoral fellowship to M.P. from Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research (FP01022963).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Menezes MR, Balzeau J & Hagan JP 3’ RNA Uridylation in Epitranscriptomics, Gene Regulation, and Disease. Front Mol Biosci 5, 61, doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00061 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadumuri RV & Janga SC Epitranscriptomic Code and Its Alterations in Human Disease. Trends Mol Med 24, 886–903, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.07.010 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S Mechanism of N(6)-methyladenosine modification and its emerging role in cancer. Pharmacol Ther 189, 173–183, doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.011 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T & He C Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curinha A, Oliveira Braz S, Pereira-Castro I, Cruz A & Moreira A Implications of polyadenylation in health and disease. Nucleus 5, 508–519, doi: 10.4161/nucl.36360 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang H et al. Terminal Uridylyltransferases Execute Programmed Clearance of Maternal Transcriptome in Vertebrate Embryos. Mol Cell 70, 72–82 e77, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim J et al. Mixed tailing by TENT4A and TENT4B shields mRNA from rapid deadenylation. Science 361, 701–704, doi: 10.1126/science.aam5794 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Pen J et al. Terminal uridylyltransferases target RNA viruses as part of the innate immune system. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 778–786, doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0106-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan M et al. mRNA 3’ uridylation and poly(A) tail length sculpt the mammalian maternal transcriptome. Nature 548, 347–351, doi: 10.1038/nature23318 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JE, Yi H, Kim Y, Chang H & Kim VN Regulation of Poly(A) Tail and Translation during the Somatic Cell Cycle. Mol Cell 62, 462–471, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.007 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Towler BP, Jones CI, Harper KL, Waldron JA & Newbury SF A novel role for the 3’−5’ exoribonuclease Dis3L2 in controlling cell proliferation and tissue growth. RNA Biol 13, 1286–1299, doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1232238 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Towler BP & Newbury SF Regulation of cytoplasmic RNA stability: Lessons from Drosophila. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 9, e1499, doi: 10.1002/wrna.1499 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viegas SC, Silva IJ, Apura P, Matos RG & Arraiano CM Surprises in the 3’-end: ‘U’ can decide too! FEBS J 282, 3489–3499, doi: 10.1111/febs.13377 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warkocki Z et al. Uridylation by TUT4/7 Restricts Retrotransposition of Human LINE-1s. Cell 174, 1537–1548, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.022 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang HM, Triboulet R, Thornton JE & Gregory RI A role for the Perlman syndrome exonuclease Dis3l2 in the Lin28-let-7 pathway. Nature 497, 244–248, doi: 10.1038/nature12119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ustianenko D et al. TUT-DIS3L2 is a mammalian surveillance pathway for aberrant structured non-coding RNAs. EMBO J 35, 2179–2191, doi: 10.15252/embj.201694857 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ustianenko D et al. Mammalian DIS3L2 exoribonuclease targets the uridylated precursors of let-7 miRNAs. RNA 19, 1632–1638, doi: 10.1261/rna.040055.113 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirouz M, Du P, Munafo M & Gregory RI Dis3l2-Mediated Decay Is a Quality Control Pathway for Noncoding RNAs. Cell Rep 16, 1861–1873, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.025 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malecki M et al. The exoribonuclease Dis3L2 defines a novel eukaryotic RNA degradation pathway. EMBO J 32, 1842–1854, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubas M et al. Exonuclease hDIS3L2 specifies an exosome-independent 3’−5’ degradation pathway of human cytoplasmic mRNA. EMBO J 32, 1855–1868, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.135 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labno A et al. Perlman syndrome nuclease DIS3L2 controls cytoplasmic non-coding RNAs and provides surveillance pathway for maturing snRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 10437–10453, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw649 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Astuti D et al. Germline mutations in DIS3L2 cause the Perlman syndrome of overgrowth and Wilms tumor susceptibility. Nat Genet 44, 277–284, doi: 10.1038/ng.1071 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Triboulet R, Pirouz M & Gregory RI A Single Let-7 MicroRNA Bypasses LIN28 Mediated Repression. Cell Rep 13, 260–266, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.086 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornton JE et al. Selective microRNA uridylation by Zcchc6 (TUT7) and Zcchc11 (TUT4). Nucleic Acids Res 42, 11777–11791, doi: 10.1093/nar/gku805 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton JE, Chang HM, Piskounova E & Gregory RI Lin28-mediated control of let-7 microRNA expression by alternative TUTases Zcchc11 (TUT4) and Zcchc6 (TUT7). RNA 18, 1875–1885, doi: 10.1261/rna.034538.112 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagan JP, Piskounova E & Gregory RI Lin28 recruits the TUTase Zcchc11 to inhibit let-7 maturation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 1021–1025, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1676 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim B & Kim VN fCLIP-seq for transcriptomic footprinting of dsRNA-binding proteins: Lessons from DROSHA. Methods, doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.06.004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ascano M, Hafner M, Cekan P, Gerstberger S & Tuschl T Identification of RNA-protein interaction networks using PAR-CLIP. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 3, 159–177, doi: 10.1002/wrna.1103 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell RB HITS-CLIP: panoramic views of protein-RNA regulation in living cells. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 1, 266–286, doi: 10.1002/wrna.31 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ule J, Hwang HW & Darnell RB The Future of Cross-Linking and Immunoprecipitation (CLIP). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032243 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheeler EC, Van Nostrand EL & Yeo GW Advances and challenges in the detection of transcriptome-wide protein-RNA interactions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 9, doi: 10.1002/wrna.1436 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee FCY & Ule J Advances in CLIP Technologies for Studies of Protein-RNA Interactions. Mol Cell 69, 354–369, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.005 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang H, Lim J, Ha M & Kim VN TAIL-seq: genome-wide determination of poly(A) tail length and 3’ end modifications. Mol Cell 53, 1044–1052, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.007 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khajuria RK et al. Ribosome Levels Selectively Regulate Translation and Lineage Commitment in Human Hematopoiesis. Cell 173, 90–103 e119, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.036 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brogna S Nonsense mutations in the alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Drosophila melanogaster correlate with an abnormal 3’ end processing of the corresponding pre-mRNA. RNA 5, 562–573 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West S, Zaret K & Proudfoot NJ Transcriptional termination sequences in the mouse serum albumin gene. RNA 12, 655–665, doi: 10.1261/rna.2232406 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rissland OS & Norbury CJ Decapping is preceded by 3’ uridylation in a novel pathway of bulk mRNA turnover. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16, 616–623, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pirouz M et al. Destabilization of pluripotency in the absence of Mad2l2. Cell Cycle 14, 15961610, doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1026485 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG & Bartel DP An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294, 858–862, doi: 10.1126/science.1065062 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reimao-Pinto MM et al. Molecular basis for cytoplasmic RNA surveillance by uridylation-triggered decay in Drosophila. EMBO J 35, 2417–2434, doi: 10.15252/embj.201695164 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faehnle CR, Walleshauser J & Joshua-Tor L Mechanism of Dis3l2 substrate recognition in the Lin28-let-7 pathway. Nature 514, 252–256, doi: 10.1038/nature13553 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa H et al. Truncated forms of U2 snRNA (U2-tfs) are shunted toward a novel uridylylation pathway that differs from the degradation pathway for U1-tfs. RNA Biol 15, 261268, doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1408766 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eckwahl MJ, Sim S, Smith D, Telesnitsky A & Wolin SL A retrovirus packages nascent host noncoding RNAs from a novel surveillance pathway. Genes Dev 29, 646–657, doi: 10.1101/gad.258731.115 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bogenhagen DF & Brown DD Nucleotide sequences in Xenopus 5S DNA required for transcription termination. Cell 24, 261–270 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuzaki H, Kassavetis GA & Geiduschek EP Analysis of RNA chain elongation and termination by Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III. J Mol Biol 235, 1173–1192, doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1072 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]