Abstract

The lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA) recognizes altered glycosylation in solid cancers and the identification of HPA binding partners in tumour tissue and serum is an important aim. Among the many HPA binding proteins, IgA1 has been reported to be the most abundant in liver metastases. In this study, the glycosylation of IgA1 was evaluated using serum samples from patients with breast cancer (BCa) and the utility of IgA1 glycosylation as a biomarker was assessed. Detailed mass spectrometric structural analysis showed an increase in disialo-biantennary N-linked glycans on IgA1 from BCa patients (p < 0.0001: non-core fucosylated; p = 0.0345: core fucosylated) and increased asialo-Thomsen–Friedenreich antigen (TF) and disialo-TF antigens in the O-linked glycan preparations from IgA1 of cancer patients compared with healthy control individuals. An increase in Sambucus nigra binding was observed, suggestive of increased α2,6-linked sialic acid on IgA1 in BCa. Logistic regression analysis showed HPA binding to IgA1 and tumour size to be significant independent predictors of distant metastases (χ2 13.359; n = 114; p = 0.020) with positive and negative predictive values of 65.7% and 64.6%, respectively. Immunohistochemical analysis of tumour tissue samples showed IgA1 to be detectable in BCa tissue. This report provides a detailed analysis of serum IgA1 glycosylation in BCa and illustrates the potential utility of IgA1 glycosylation as a biomarker for BCa prognostication.

Keywords: breast cancer, ELISA, glycosylation, IgA, lectin

1. Introduction

Altered protein glycosylation is a feature of carcinogenesis, profoundly affecting protein structure (and function) and cancer cell behaviour. The lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA) recognizes aberrant glycosylation in breast cancer (BCa) [1] and is associated with the propensity of cancer cells to metastasize and with poor patient prognosis [2–7]. HPA has nominal binding specificity for N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) but also recognizes other structures including the Forssman antigen, blood group A antigen [8,9], Tn antigen [10], sialic acid (SA) [7,11] and N-acetylyglucosamine (GlcNAc) [11–13]. HPA binding partners include: integrin α4/α6 and annexin 2, 4 and 5 in colorectal cancer [14,15] and in metastatic BCa: enolase 1, heat shock protein 27 and heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear proteins (HnRNP) H1, HnRNP D-like and HnRNP A2/B1 [13]. Studies with serum from BCa patients have identified immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1), complement protein C3, alpha-2-macroglobulin, cadherin V and polyimmunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) as HPA binding proteins [16,17]. Previous work carried out by our group has identified IgA1 as a significant HPA binding protein in BCa metastases to the liver [18].

IgA is the most abundant antibody isotype in humans, present in serum, tissues and mucosal secretions including breast milk [19–21]. IgA1 and IgA2 differ by virtue of a 13 amino acid hinge region (present in IgA1 only), located between conserved regions 1 and 2 of the heavy chain of the antibody [19,22]. IgA1 and IgA2 exist as mono-, di-and polymers (pIgA); multimeric IgA monomers are linked by a joining chain (J-chain). Mucosal IgA is mostly pIgA2 with some pIgA1 produced by local B cells. By contrast, serum IgA produced in the bone marrow is mostly monomeric IgA1 [22]. The hinge region of IgA1 has nine potential sites for O-linked glycosylation, between three and five of which have been reported as occupied [23–26], Thr228, Ser230, Ser232 consistently while Thr225 and Thr236 occasionally are occupied [25,27]. O-linked glycans located at the hinge region of IgA1 consist of GalNAc, galactose (Gal) and SA residues. Two N-linked glycans are found on each heavy chain (Asn263/Asn459) and these have been reported to be mainly the complex digalactosylated biantennary type [24,27,28].

Truncated O-linked glycans have been observed in the hinge region of IgA1 in IgA nephropathy (IgAN) [26,29–35] and Henoch–Schönlein pupura [36]. Altered glycoforms of IgA1 are also detectable in BCa metastases to the liver [18]. In IgAN, the IgA1 molecules display increased levels of terminal GalNAc (the Tn antigen) [33,35,37]. This truncated structure, recognized by HPA, has been reported to be a marker of poor prognosis and aggressive BCa [38–40]. A recent report has shown that IgA1 is detectable in primary BCa tissues and array technology has revealed that HPA will bind synthetic IgA1 glycopeptides modified with GalNAc residues [41]. The underlying biochemical basis for the observed changes in IgA1 glycosylation in cancer is unclear and the functional significance of this change in cancer remains elusive.

The aim of this study was to measure the levels of IgA1 in the serum of BCa patients and explore whether the IgA1 glycosylation is altered by comparison with serum from healthy women. The levels of IgA1 and glycosylation were assessed using an enzyme-linked lectin assay (ELLA). Detailed mass spectrometric glycan structural analysis of affinity-purified IgA1 was undertaken. N-linked glycosylation was observed to be significantly altered in serum from BCa patients compared with serum of healthy women. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed, with HPA binding to IgA1 and tumour size emerging as significant independent predictors for the formation of distant metastases. Altered IgA1 glycosylation may modulate IgA1 function and is a useful biomarker for BCa prognosis.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Materials

All materials were purchased from Sigma, Poole, UK, unless otherwise stated. Maxisorp 96-well plates were from Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA, and the polyclonal sheep anti-human IgA1 (AU087) and polyclonal sheep anti-human IgA horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (AP010) were purchased from The Binding Site, Birmingham, UK.

2.2. Serum samples

Approval for this study was granted by the North London Research Ethics Committee (ref. 10/0258). Blood samples were collected from healthy women (normal healthy women, N) attending the ‘one-stop’ breast clinic at University College London Hospital (UCLH), London, UK. These women were clinically, mammographically and/or cytologically confirmed to be clear of BCa. Venous blood was collected, centrifuged at 400g for 15 min and the supernatant (serum) retained. For IgA1 affinity purification, samples from women with BCa (table 1) were selected from the DietCompLyf study, an ongoing multi-centre observational study run by our unit [42]. The serum samples from all of the cancer patients were drawn 12 ± 3 months after diagnosis. Eight samples were used for IgA1 purification and glycan mapping (normal healthy women, N, n = 4; BCa (BCa) n = 4). A larger set of N and BCa samples (table 2 and electronic supplementary material, table SI) were used to measure the levels of IgA1, captured with polyclonal sheep anti-human IgA1 (Binding Site, AU087), and glycosylation of IgA1 by ELISA and ELLA, respectively. The blood type of each serum sample was determined as detailed in Markiv et al. [12] (table 2).

Table 1.

Samples used for the IgA1 purification and glycan analysis. Serum was collected from healthy ‘control’ individuals (HC) attending the UCLH ‘one-stop’ clinic. Patients with BCa provided serum samples 9–15 months post-diagnosis of the primary tumour and were followed up for 4 years. Mean average values are shown where relevant.

| healthy individuals (n = 4) |

cancer patients (n = 4) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | range | mean | range | |

| age at diagnosis (years) | 56.5 | 48–61 | 48 | 42–55 |

| tumour size (mm) | — | 14.5 | 13–20 | |

| grade 2 | — | 2 | ||

| grade 3 | — | 2 | ||

| no sign of recurrence (NSR) | — | 1 | ||

| distant metastases (DM) | — | 3 | ||

| lymph node positive | — | 0 | ||

| blood group A | — | 0 | ||

| blood group B | 1 | 0 | ||

| blood group O | 3 | 4 | ||

Table 2.

Clinical and pathological features of patient samples analysed in the IgA1 ELISA and ELLA. BCa patient serum samples were provided 9–15 months after diagnosis for patients who had no sign of recurrence, NSR (5 years of follow-up), and from patients that developed distant metastases, DM. The annual serum sample taken that was closest to the date of diagnosis of metastasis was used for each DM sample. Mean average values are shown where relevant. Within the full sample (n = 120): number of days to local recurrence (n = 4) 520–1240 (919 ± 361.6) days. Number of days to distant metastases (n = 57) 370–1828 (1007.6 ± 363.2) days. Number of days to death (n = 44) 738–2482 (1442 ± 449.1) days.

| total subjects (n = 120) |

no sign of recurrence (n = 63) |

distant metastases (n = 57) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| range | mean (s.d.) | range | mean (s.d.) | range | mean (s.d.) | |

| age at diagnosis (years) | 28–74 | 53.31 (10.352) | 34–73 | 54.51 (10.426) | 28–74 | 51.98 (10.197) |

| tumour size (mm) | 3–110 | 25.75 (15.1) | 3–70 | 22.8 (11.7) | 10–110 | 29.4 (18.0) |

| IgA1 level | 0.612–30.248 | 5.738 (3.501) | 1.857–12.951 | 5.485 (2.770) | 0.612–30.248 | 6.018 (4.171) |

| HPA level | 0.620–214.411 | 25.314 (26.138) | 0.620–56.125 | 21.234 (11.084) | 3.233–214.411 | 29.823 (35.726) |

| HPA : IgA ratio | 0.06–49.97 | 5.573 (5.96) | 0.06–15.76 | 4.836 (3.368) | 0.25–49.97 | 6.388 (7.845) |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grade 1 | 11 | 9.2 | 8 | 12.7 | 3 | 5.3 |

| grade 2 | 53 | 44.2 | 27 | 42.9 | 26 | 46.4 |

| grade 3 | 55 | 45.8 | 28 | 44.4 | 27 | 47.4 |

| unknown | 1 | 0.8 | — | — | 1 | 1.8 |

| lymph node positive | 77 | 64.2 | 38 | 60.3 | 39 | 68.4 |

| lymph node negative | 43 | 35.8 | 25 | 39.7 | 18 | 31.6 |

| chemotherapy—yes | 95 | 79.2 | 46 | 27.0 | 49 | 86.0 |

| chemotherapy—no | 25 | 20.8 | 17 | 73.0 | 8 | 14.0 |

| radiotherapy–yes | 102 | 85.0 | 10 | 15.9 | 8 | 14.0 |

| radiotherapy–no | 18 | 15.0 | 53 | 84.1 | 49 | 86.0 |

| blood group A | 45 | 37.5 | 26 | 41.9 | 19 | 32.8 |

| blood group B | 13 | 10.8 | 6 | 9.7 | 7 | 12.1 |

| blood group AB | 11 | 9.2 | 5 | 8.1 | 6 | 10.3 |

| blood group O | 51 | 42.5 | 25 | 40.3 | 26 | 44.8 |

| smoking status: | ||||||

| current | 9 | 7.5 | 6 | 9.5 | 3 | 5.3 |

| never | 72 | 60.0 | 32 | 50.8 | 40 | 70.2 |

| past | 38 | 31.7 | 24 | 38.1 | 14 | 24.6 |

| unknown | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.6 | — | — |

2.3. IgA1 ELISA

IgA1 levels were determined with an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Ninety-six-well plates were coated with 50 µl well−1 of 2 µg ml−1 anti-IgA1 (AU087) in coating buffer (0.1 M carbonate/bicarbonate buffer pH 9.4) overnight at 4°C. Subsequent steps were performed at room temperature on an orbital shaker. The plates were washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% (v/v) Tween20 (PBST) and blocked with 200 µl Carbo-Free (Vector Laboratries, Peterborough, UK) for 30 min. Washing was repeated and serum samples (50 µl) diluted 1 in 80 000 in Carbo-Free were added to the wells and incubated for 2 h. The plates were washed as before and each well was probed for 1 h with 50 µl of 0.2 µg ml−1 anti-human IgA-HRP (AP010) in Carbo-Free. The plates were washed three times with PBST, three times with deionized water and 100 µl TMB substrate (Insight Biotechnologies, Wembley, UK) was added for 2 min. The reaction was quenched with 100 µl 1 M phosphoric acid and the absorbance measured at 450 nm (Wallac Victor 2 1420 plate reader; Perkin Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK). Each plate included serial dilutions (6–400 ng ml−1) IgA1 previously isolated from pooled normal human serum (National Blood Service, Colindale, London, UK). Briefly, IgA1 was purified from pooled normal serum by ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by Jacalin agarose (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) affinity chromatography. The bound fraction was eluted with 1 M Gal and subjected to buffer exchange.

2.4. Enzyme-linked lectin assay

To assess the glycosylation of IgA1, the ELISA described above was modified to include the lectins HPA, Sambucus nigra (SNA) and Maackia amurensis lectin II (MAL-II) as detection reagents in place of a detection antibody. The ELLA used the same equipment and approach as above. Plates were coated as before with antibody diluted in PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After washing three times with PBST the plates were blocked as before, washed three times with PBST and 50 µl of serum sample (diluted 1 in 5, 1 in 10 or 1 in 20 in Carbo-Free for the HPA ELLA and 1 in 32 000 in Carbo-Free for the SNA/MAL-II ELLA) was applied in duplicate wells for 30 min at 37°C. The plate was washed and 50 µl of 10 µg ml−1 HPA-biotin (Sigma, Poole, UK), MAL-II-biotin or SNA-biotin (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) in Carbo-Free was added for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with gentle rocking three times with PBST, 50 µl of 0.25 µg ml−1 poly-streptavidin-HRP (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) in Carbo-Free was added to each well for 1 h, the plate was washed again with PBST, three times with distilled water and 100 µl of TMB substrate was applied to each well for 1–15 min. The reaction was quenched and the absorbance was measured as before. For the initial HPA and the SNA/MAL-II ELLA, pooled serum was used as a reference material. For the later HPA ELLA, a standard using IgA from human colostrum (0.78–50 µg ml−1) was used.

2.5. ELISA and ELLA sample analysis

For the initial HPA and SNA ELLA, the mean absorbance values measured in samples from healthy women and women with BCa were compared using an unpaired Student's t-test. In the assays where the reference material was run on each 96-well plate, the mean value for each standard curve from each plate was used to create a ‘master standard curve’. The ‘master blank’ was subtracted from the mean absorbance reading for each sample, and this value was measured against the master standard curves to provide the IgA1 or HPA binding level.

2.6. Iga1 purification

In total, 0.5 mg of anti-IgA1 (AU087) was coupled to a 1 ml NHS-activated HiTrap column (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Three hundred microlitres of serum was clarified by centrifugation at 10 000g for 15 min, diluted to a final volume of 1 ml in PBS, applied to the column and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The column was washed with five column volumes of PBS and IgA1 was eluted with five column volumes of 0.1 M glycine pH 2.7, neutralized immediately with 70 µl of 1 M TRIS–HCl, pH 9.0. Buffer exchange into PBS was performed using an Amicon centrifugation filter unit (10 kDa molecular weight cut off; Millipore, MA, USA). Protein yield was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

2.7. Breast cancer tissue sample analysis

To determine whether the IgA1 was detectable in BCa tissues, four frozen BCa tissue samples (50 mg wet weight) were homogenized in lectin buffer (0.05 M TBS, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.6) using a handheld homogenizer for 5 min with intermittent cooling on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 15 000g and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until required. IgA1 immunohistochemistry was performed using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast tissues (n = 4) from the same patients. The samples were processed according to Brooks & Leathem [6]: the sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, blocked and probed with 20 µg ml−1 biotinylated anti-IgA1 (AU087) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with 5 µg ml−1 streptavidin-HRP in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and detection with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) prepared in PBS/H2O2. After labelling, the slides were counter-stained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted.

Protein samples (10 µg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using the discontinuous buffer system described by Laemmli [43]. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or used for western blot transfer. Membranes were blocked with Carbo-Free overnight at 4°C, washed 3 × 5 min with PBST and probed with either biotinylated anti-IgA1 (AU087, 0.1 µg ml−1), HPA (10 µg ml−1), MAL-II (0.5 µg ml−1) or SNA (0.5 µg ml−1) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed as before and incubated with 2 µg ml−1 streptavidin-HRP in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, washed again and probed with DAB. The blot images were captured using a scanning densitometer (GS-710; Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

2.8. Glycan purification

A total of 40–50 µg of IgA1 was processed for mass spectrometry using the procedure of Sutton-Smith & Dell [44]. Each sample was reduced in 0.6 M Tris/4 M guanidine-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, with dithiothreitol (DTT) at 2 mg ml−1 for 2 h at 50°C. Carboxymethylation was performed with 12 mg ml−1 iodoacetic acid in tris buffer pH 8.5, in the dark for 2 h at room temperature. To terminate the reaction, samples were dialysed against 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, at 4°C for 48 h. Samples were lyophilized and digested with trypsin at a ratio of 50 : 1 (w/w) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.5 for 24 h at 37°C. The enzyme reaction was terminated by addition of one drop of acetic acid. Peptides and glycopeptides were separated from hydrophilic impurities on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters Corp., MA, USA) and lyophilized. N-glycans were released from the glycopeptides with six units of peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase-F; Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer, pH 8.4, for 24 h at 37°C. The released N-glycans were separated from peptides and O-glycopeptides on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. O-glycans were released from the peptide/O-glycopeptide mixture by reductive elimination; 400 µl of 1 M potassium borohydride in 0.1 M potassium hydroxide was added to each sample and the mixture was incubated for 16 h at 45°C; again the reaction was terminated by the drop-wise addition of acetic acid. The samples were deionized by Dowex chromatography and borates were removed. The pools of N- and O-glycans were permethylated using the sodium hydroxide permethylation procedure and purified once more using Sep-Pak C18 cartridges.

2.9. Mass spectrometry of glycans

As detailed in Antonopoulos et al. [45], permethylated glycan samples were solubilized in 10 µl methanol, 0.5 µl of the sample was then mixed with 0.5 µl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) matrix (20 mg ml−1 in 70% v/v methanol in water), spotted onto a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) target plate and dried under vacuum. MS data were acquired using either a Voyager-DE STR MALDI-time of flight (TOF) or a 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) mass spectrometer. MS/MS data were acquired using a 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer. For the MS/MS studies, the collision energy was set to 1 kV, and argon was used as the collision gas. The 4700 Calibration Standard Kit: Calmix (Applied Biosystems) was used as the external calibrant for the MS mode, and human [Glu1] fibrinopeptide B was used as an external calibrant for the MS/MS mode.

2.10. Analyses of MALDI data

The MS and MS/MS data were processed using Data Explorer 4.9 software (Applied Biosystems). Processed spectra were subjected to manual peak assignment and annotation using GlycoWorkBench [46]. The assignments for selected peaks were based on mass composition of the 12C isotope together with current knowledge of biosynthetic pathways. The proposed structures from the MS mode were confirmed by data obtained from MS/MS experiments. Data obtained were compared using an unpaired Student's t-test.

2.11. Experimental design and statistical rationale

Eight samples were used for IgA1 purification and glycan mapping (normal healthy women, N, n = 4; BCaBCa, n = 4). For the initial HPA ELLA, 14 BCa samples were analysed. For the larger dataset, 120 BCa samples were analysed for IgA level and HPA binding. In these assays, 15 and 14 healthy control samples were also analysed, respectively. For the SNA ELLA, 11 BCa samples were compared with 11 healthy control samples. For all ELISAs and ELLAs samples were analysed in duplicate. Data were log transformed and an unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare data from healthy women and patients.

The data from the IgA1 and HPA assays were further analysed as continuous variables and evaluated using the logistic regression technique with clinical and tumour characteristics assessed (tables 1 and 2). Variables which showed significant (less than 0.05) association with the formation of distant metastases were built into the final model in a stepwise manner until a stable model was achieved. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to assess how well the variables predict distant recurrence. The sensitivity, specificity and the negative and positive predictive values were determined.

Data obtained from mass spectrometry analyses were compared using an unpaired Student's t-test.

3. Results

3.1. ELISA and ELLA

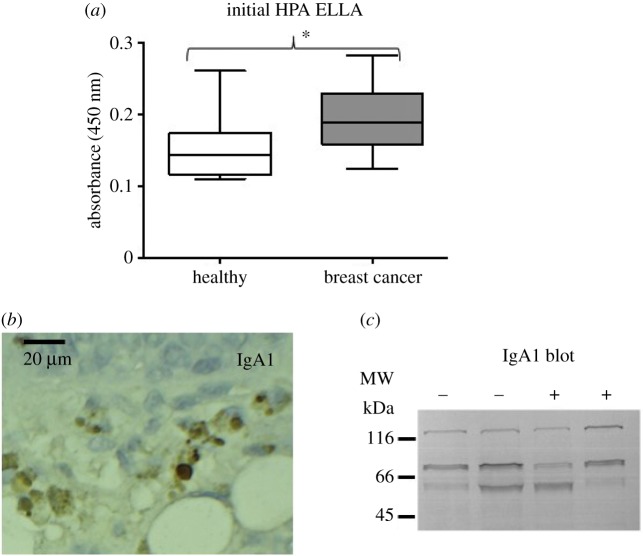

The aim of this study was to evaluate the glycosylation of IgA1 from women with BCa and compare this with IgA1 from age-matched healthy women, confirmed to be free of BCa (normal healthy individuals; N). The initial ELISA and ELLA analysis indicated that HPA bound to IgA1 from the BCa samples to a greater extent than to IgA from normal healthy individuals (figure 1; mean healthy A450 = 0.1533 compared with patient A450 = 0.1941, p = 0.02).

Figure 1.

Breast cancer IgA1: serum and tissue analysis. (a) HPA binding to serum IgA1 from normal healthy individuals (n = 15) and BCa patients (n = 14) was assessed by ELLA with HPA as the detection reagent. IgA1 was captured using a polyclonal sheep anti-human IgA1 antibody and the mean average optical density ± s.e.m. at l 450 nm is shown. HPA binding to IgA1 was significantly increased in the serum of BCa patients compared with normal healthy individuals (Student's t-test, p = 0.0205). (b) Representative example of IgA1 immunohistochemistry with 5 µm FFPE breast cancer tissue. The tissue samples were probed with biotinylated anti-IgA1 antibody, streptavidin-HRP and DAB-H2O2 (brown). The nuclei were counter-stained with haematoxylin (blue). (c) Protein preparations (10 µg) from four breast cancer tissue samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, subjected to western transfer and probed with biotinylated anti-IgA1, streptavidin-HRP and DAB-H2O2. Lanes 1 and 2 are from patients who were lymph node negative (−) and lanes 3 and 4 are from lymph node-positive patients (+). (Online version in colour.)

3.2. IgA1 breast tissue immunochemistry and protein separation

FFPE primary BCa specimens were probed with sheep polyclonal anti-IgA1 and, in common with the recent report by Welinder et al. [41], all the samples showed reactivity with the antibody, confirming the presence of IgA1 in these tissues (figure 1). Protein preparations from the same tumour tissues were separated by SDS-PAGE and western blotted and probed with the same anti-IgA1 antibody, verifying the findings of the immunochemistry (figure 1).

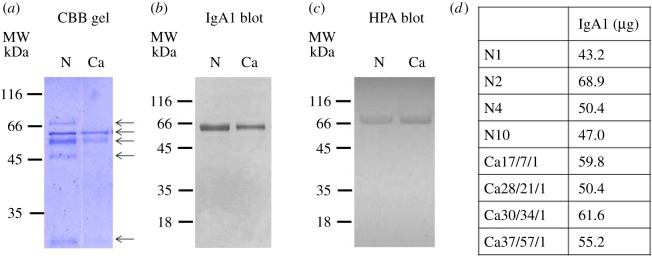

IgA1 was affinity purified from four BCa patient serum samples and four healthy samples (table 1). The preparations were analysed using SDS-PAGE: protein bands at 69, 58, 52, 45 and 25 kDa were observed, consistent with the light chain (25 kDa) and heavy chain (58 kDa) of IgA1 (figure 2). The band observed (in some samples) at 69 kDa appears to represent the secretory component of IgA1 (figure 2). The western blot probed with anti-IgA1 confirmed the data from the SDS-PAGE analysis. HPA was observed to bind preferentially to the heavy chain of IgA1 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

IgA1 purification from serum samples. IgA1 was affinity purified from the serum of normal healthy controls (n = 4) and patients with breast cancer (n = 4). The purified IgA1 was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (a) or western transferred and probed with biotinylated anti-IgA1 (b) or HPA (c); the bands were visualized by incubation with streptavidin-HRP and DAB-H2O2. IgA1 purified from normal healthy individuals (N) and breast cancer patients (Ca) are shown. (d) Table details IgA1 yield from normal healthy individuals (N) and breast cancer patients (Ca) subsequently used for glycan release. (Online version in colour.)

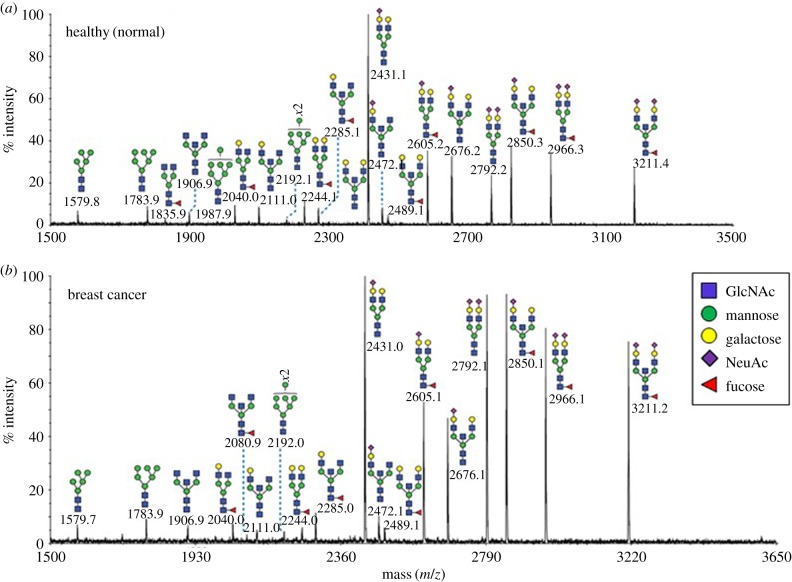

3.3. N-glycosylation

Detailed mass spectrometric glycan structural analysis of the affinity-purified IgA1 preparations (figure 3) revealed N-linked glycans of the complex type previously observed in IgA1 from healthy individuals [27,28]. MS/MS analysis confirmed that the glycans were core fucosylated, mainly biantennary with some bisecting GlcNAc structures (for example, m/z 2111, 2315, 2489 and 3211). The non-reducing termini were either unmodified (m/z 2244, 2315, 2489) or substituted with SA residues (m/z 2431, 2605, 2792, 2966). While the BCa patient IgA1 exhibited similar N-glycans to IgA1 from normal healthy samples, the relative abundance of terminating SA was increased in the patient samples.

Figure 3.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of permethylated N-glycans of IgA1 purified from serum samples. N-glycan profiles of IgA1 from (a) normal healthy individuals (n = 4) and (b) breast cancer patients (n = 4) are shown. Additional spectra are provided in the electronic supplementary material, figure S3. Annotated structures are according to the Consortium for Functional Glycomics guidelines. Molecular ions are [M + Na]+. Depicted spectra are from the 50% MeCN fractions from a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. Putative structures are based on composition, MS/MS and knowledge of biosynthetic pathways. (Online version in colour.)

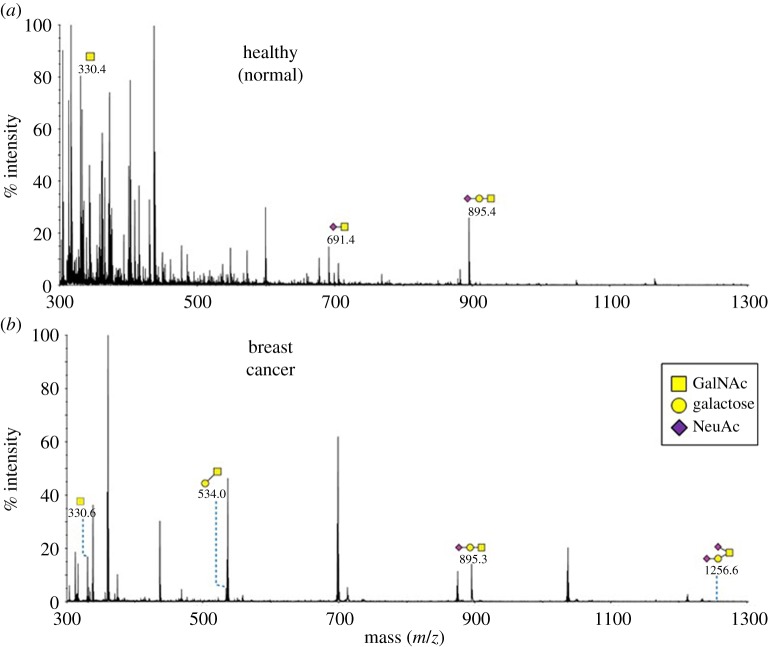

3.4. O-glycosylation

Very low amounts of O-glycans were released from the IgA1 preparations (figure 4). This may be due to the relatively low quantity of protein used for glycan release. Nevertheless, structures consistent with those previously reported on the hinge region of IgA1 were observed (notably, m/z 691, 895) in the preparations from both the healthy individuals and BCa patients. Structures at m/z 534 and 1256 were only detectable in the patient samples; these glycans were consistent with asialo-TF and disialo-TF antigen, respectively.

Figure 4.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of permethylated O-glycans of IgA1 purified from serum samples. O-glycan profiles of IgA1 from (a) normal healthy individuals (n = 4) and (b) breast cancer patients (n = 4) are shown. Additional spectra are provided in the electronic supplementary material, figure S4. Annotated structures are according to the Consortium for Functional Glycomics guidelines. Molecular ions are [M + Na]+. Depicted spectra are from the 35% MeCN fractions from a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge. Putative structures are based on composition, MS/MS and knowledge of biosynthetic pathways. (Online version in colour.)

3.5. IgA1 and HPA ELISA validation set

The results from the initial serum IgA1 glycosylation ELLA above were assessed further using additional samples from an independent sample set comprising healthy individuals (n = 14) and women with BCa (n = 120) (table 2). All patients and nine of the samples from healthy individuals displayed detectable levels of HPA binding but when the data were compared using the Student's t-test no significant differences in binding were observed between the HPA status of IgA1 from patients and normal healthy women (electronic supplementary material, figure S1; p = 0.6856). Extensive clinical, pathological and follow-up information was available for the individuals included in this validation study (electronic supplementary material, table SI). Logistic regression analysis was performed followed by the χ2-test to determine how well the logistic regression model fitted the data. Both HPA binding and tumour size emerged as significant independent predictors of distant metastases (χ2 = 13.359; p = 0.020).

A potential confounding variable is the cross-reactivity between HPA and terminal GalNAc of the blood group A antigen [16]. The samples evaluated in this study were tested for blood type and this was included in the logistic regression analysis but there was no significant association between blood group and formation of distant metastases (tables 2 and 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Table 3.

Blood group distribution across the serum samples. The blood group was determined for all serum samples analysed in this study. The distribution of blood groups among the samples was similar to that observed in the UK population (https://www.blood.co.uk/why-give-blood/the-need-for-blood/know-your-blood-group).

| blood group | study samples (%) | UK population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 36 | 42 |

| B | 11 | 10 |

| O | 45 | 44 |

| AB | 8 | 4 |

Changes in serum IgA1 levels have been reported in women with BCa [47–50]. All the samples tested in this study had detectable levels of IgA1; however, there was no statistically significant difference between the IgA1 level of healthy individuals and the BCa patients, irrespective of whether or not the patients went on to develop distant metastases (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The sensitivity and specificity of the model were 35.3% and 81.0%, respectively, and the positive predictive value and negative predictive value were 60% and 60.7%, respectively.

3.6. Increased sialylation of N-glycans of IgA1 in breast cancer

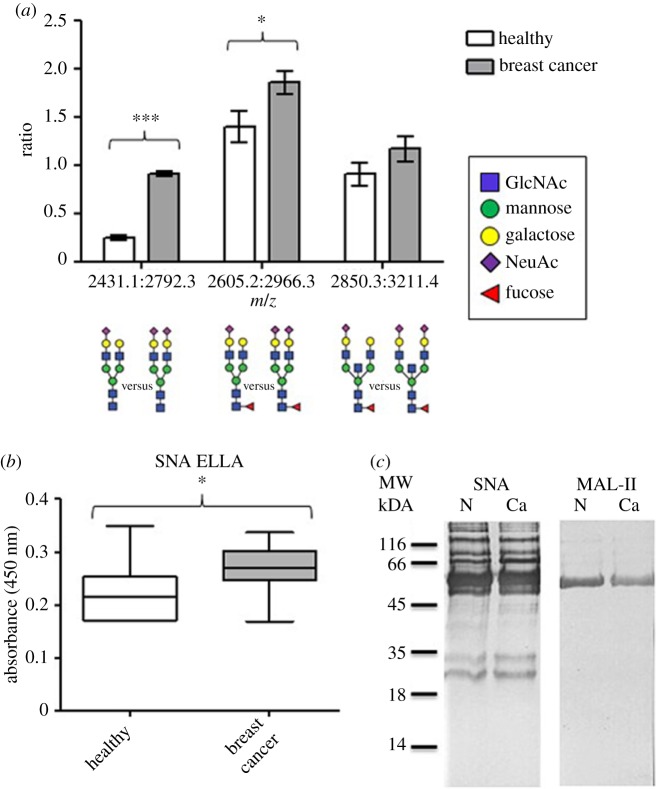

Increased SA substitution of N-glycans and O-glycans has previously been reported in cancer [39,51]. Mass spectrometry was used to investigate the IgA1 sialylation and the ratio of ions with m/z 2792: 2431; 2966: 2605 and 3211: 2850, correlating with mono- or di-sialylated N-glycan structures were compared (figure 5). Di-sialylated structures were found in higher abundance in the BCa patient samples than in the samples from healthy women (figure 5; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0345).

Figure 5.

IgA1 from breast cancer patient samples displays increased α2,6-linked sialylation. (a) The ratios of three mono-sialylated and di-sialylated biantennary N-linked glycan structures were compared using a Student's t-test, m/z 2792 : 2431 (p < 0.0001), 2966 : 2605 (p = 0.0345) and 3211 : 2850 (not significant). (b) The level of SNA binding to IgA1 in serum from normal healthy individuals (n = 11) and BCa patients (n = 11) was assessed by ELLA with SNA as the detection reagent. IgA1 was captured using a polyclonal sheep anti-human IgA1 antibody and the mean average optical density ± s.e.m. at l 450 nm is shown. SNA binding to IgA1 was significantly increased in the serum of BCa patients compared with normal healthy individuals (Student's t-test, p = 0.0335). (c) Protein preparations (10 µg) from serum samples from healthy individuals and breast cancer patients were separated by SDS-PAGE, western transferred and probed with biotinylated SNA or MAL-II, and visualized using streptavidin-HRP and DAB-H2O2. Lanes 1 and 2 are from normal healthy individuals (N) and breast cancer patient samples (Ca) as indicated. (Online version in colour.)

Sialylation of IgA1 was assessed by incorporating the lectins SNA and MAL-II into the ELLA system to enable evaluation of α2,6- and α2,3-linked SA. The SNA binding level was increased in the IgA1 captured from serum from BCa patients compared with that from healthy women (figure 5; mean A450: patient, 0.2662; healthy women, 0.2200; p = 0.03; n = 11 in both groups). Western blot analysis showed that SNA bound to both the heavy and light chains of IgA1 from the BCa preparations, suggestive of an increase in α2,6-linked SA.

4. Discussion

In this study, the glycosylation of IgA1 from women with metastatic and non-metastatic BCa was compared with IgA1 from normal healthy women. Initial work in which HPA was used to assess the glycosylation of IgA1 used an ELLA incorporating HPA as the detection reagent. This assay was developed in house and with a relatively small number of serum samples. In this initial experiment, HPA was observed to bind IgA1 in serum samples from BCa patients to a greater extent than IgA1 in serum samples from normal healthy control women, confirming that serum IgA1 glycosylation is altered in BCa. A larger independent set of BCa serum samples collected as part of the DietCompLyf study were analysed (n = 120). Although all patients and nine of the samples from healthy individuals displayed detectable levels of HPA binding, no significant differences were observed between the HPA binding level to IgA1 from patients and normal healthy women. The relatively small numbers of serum samples assessed from healthy women in this study may be of relevance but analysis of further serum samples from women confirmed (preferably mammographically) to be clear of BCa requires testing to either confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Analysis of the HPA binding status of the BCa patient data using logistic regression showed HPA binding and tumour size to be statistically significant predictors of distant metastases (p = 0.020). In the univariate analysis, lymph node status was associated with distant metastasis formation but in the multivariate model lymph node status no longer remained a statistically significant independent variable. It is worth noting, however, that lymph node status in the multivariate model was driven by a single lymph node-positive patient with a 2 cm tumour, who somewhat surprisingly had remained metastasis free for 5 years post diagnosis, and whose results skewed the data distribution.

Treatment regimens (chemotherapeutic or radiological) and behavioural factors (for example, smoking) would be predicted to affect the immune status of an individual and therefore the circulating IgA1 levels [52–54]. In this study the majority of the patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (79%), post-operative external beam radiotherapy (85%) and were either ‘past’ or ‘never’ smokers (91%). Serum samples from the patients were collected after they had received such treatment. These factors were included in the stepwise analysis model and the only significant association between IgA glycosylation and the formation of distant metastases was tumour size.

When the glycans from affinity-purified IgA1 were released and analysed using mass spectrometry an increase in both the TF antigen (in the O-glycan pool) and sialylation (of the N-glycans) was observed in the serum IgA1 from patients with BCa. The time-consuming nature of glycan release and mapping experiments, coupled with the relatively large (µg) sample requirements compared with an ELISA system [55], rendered this approach unsuitable for high-throughput sample analysis for our study. Accordingly, our methodology in which an ELISA was adapted to incorporate the lectins SNA and MAL-II as the detection reagents was adopted, and this confirmed an increase in α2,6 sialylation of IgA1 in the BCa patient samples.

It is not clear whether the IgA1 detected in the serum of the cancer patients, reported here, derived from tumour infiltrating or circulating B-lymphocytes or from residual disease. There have been reports of cancer cell lines producing immunoglobulin chains cited in [41], and it is not inconceivable that the altered glycosyltransferase levels in cancer may result in abberant glycosylation of such chains. The clinical importance of TILs has been widely recognized but the IgA synthesized has not been evaluated in terms of the glycosylation repertoire; it would be interesting to determine if the altered glycoforms of IgA1 derive from the tumour infiltrating B-lymphocytes or from the tumour cells themselves.

Similarly, it is unclear whether the observed increase in sialylation of IgA1 in BCa is of functional significance; altered glycosylation of IgA1 may affect antigen recognition or the down-stream interaction between IgA1 and effector cells but this will require further analysis. While detailed glycopeptide mapping was beyond the scope of this study, identifying the N-glycan occupancy (at Asn263/Asn459 on the heavy chain of IgA1) and any accompanying glycan heterogeneity would also be an area of interest. Such analyses may help to unravel the potential roles for the observed changes in IgA1 glycosylation in cancer. Similarly, the immunoreactivity of the anti-IgA1 antibody with primary BCa tissue sections is intriguing and warrants further evaluation. Of particular relevance is whether the glycosylation of serum IgA1 alters localization to BCa cells. Welinder et al. [41] also reported IgA1 in BCa tissue sections, describing the increased levels of IgA1 in invasive cancer relative to in situ disease, but it is not clear if the IgA1 was bone marrow derived or if it had been secreted by immune cells located within the breast parenchyma. IgA1 is produced by luminal epithelial cells of the breast during lactation where it is associated with the secretory component of the pIgR. Interestingly pIgR was identified in a glycoproteomic study from our laboratory and found in increased levels in the serum of BCa patients with recurrent BCa [17], but, again, it is unclear if this is due to cancerous breast tissue secreting more pIgA or an autoimmune response to metastatic BCa.

Complete glycan mapping of serum proteins has been adopted as an approach for identifying biomarkers for breast and other adenocarcinomas including of pancreatic, prostate, ovarian and gastric origin [56–59]. Lectin arrays show some utility in this regard and previous reports with the use of an evanescent-field fluorescence-assisted lectin microarray have revealed subtle differences in glycosylation between metastatic and non-metastatic BCa serum glycoproteins [60]. Other studies concerned with identifying glycan cancer biomarkers in the serum have reported alterations in the sialylation of serum proteins in ovarian [61,62] and oral carcinoma [63]. In breast carcinoma, an increase in bifucosylation [59] and, more interestingly, sialylation of total serum N-linked glycans [64,65] have been reported. The use of glycosylated immunoglobulins as potential disease biomarkers has also been reported; in BCa IgG glycan profiling can distinguish patients from healthy controls [66] and aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 is documented as a potential biomarker in IgA nephropathy [35,67,68].

Serum IgA1 levels have been reported to be increased in BCa [47–50], to comprise different glycoforms in cancer [41] and have been correlated with metastasis formation [69]. This study shows that the IgA1 in the serum of BCa patients is GalNAcylated and that it also has a different, sialylated, repertoire. In conclusion, this report provides a detailed analysis of serum IgA1 glycosylation in BCa and illustrates the potential utility of IgA1 glycosylation as a biomarker for BCa prognosis. These alterations may be useful as biomarkers for cancer and may be of relevance in the context of the immune response to cancer, work is ongoing to investigate these changes further.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Ethics

Approval for this study was granted by the North London Research Ethics Committee (ref. 10/0258).

Authors' contributions

H.J.L.-B.: designed the study, undertook the laboratory work, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. C.R.: undertook the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. A.A.: assisted with the glycan analysis and reviewed the manuscript. A.J.C.L.: designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. S.M.H. and A.D.: supervised the glycan analysis and reviewed the manuscript. M.V.D.: designed the study, supervised the work, and drafted, revised and submitted the manuscript.

Data accessibility

The full dataset is provided in the electronic supplementary material.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Against Breast Cancer charity (Registered Charity no. 1121258) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (to A.D. and S.M.H.; grant nos. BBF008309 and BBK016164). The University of Westminster curates the DietCompLyf database created by and funded by Against Breast Cancer (Registered Charity no. 1121258). H.L.B. acknowledges receipt of funding from Against Breast Cancer (Registered Charity no. 1121258).

References

- 1.Leathem AJ, Brooks SA. 1987. Predictive value of lectin binding on breast-cancer recurrence and survival. Lancet 1, 1054–1056. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90482-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenlon S, Ellis IO, Bell J, Todd JH, Elston CW, Blamey RW. 1987. Helix pomatia and Ulex europeus lectin binding in human breast carcinoma. J. Pathol. 152, 169–176. ( 10.1002/path.1711520305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukutomi T, Itabashi M, Tsugane S, Yamamoto H, Nanasawa T, Hirota T. 1989. Prognostic contributions of Helix pomatia and carcinoembryonic antigen staining using histochemical techniques in breast carcinomas. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukutomi T, Hirohashi S, Tsuda H, Nanasawa T, Yamamoto H, Itabashi M, Shimosato Y. 1991. The prognostic value of tumor-associated carbohydrate structures correlated with gene amplifications in human breast carcinomas. Jpn. J. Surg. 21, 499–507. ( 10.1007/BF02470985) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alam SM, Whitford P, Cushley W, George WD, Campbell AM. 1990. Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface carbohydrates in metastatic human breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 62, 238–242. ( 10.1038/bjc.1990.267) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks SA, Leathem AJ. 1991. Prediction of lymph node involvement in breast cancer by detection of altered glycosylation in the primary tumour. Lancet 338, 71–74. ( 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90071-V) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dwek MV, Ross HA, Streets AJ, Brooks SA, Adam E, Titcomb A, Woodside JV, Schumacher U, Leathem AJ. 2001. Helix pomatia agglutinin lectin-binding oligosaccharides of aggressive breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 95, 79–85. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker DA, Sugii S, Kabat EA, Ratcliffe RM, Hermentin P, Lemieux RU. 1983. Immunochemical studies on the combining sites of Forssman hapten reactive hemagglutinins from Dolichos biflorus, Helix pomatia, Wistaria floribunda. Biochemistry 22, 2741–2750. ( 10.1021/bi00280a023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu AM, Sugii S. 1991. Coding and classification of D-galactose, N-acetyl-D-galactosamine, β-D-Galp-[1→3(4)]-β-D-GlcpNAc, specificities of applied lectins. Carbohydr. Res. 213, 127–143. ( 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)90604-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Springer GF. 1989. Tn epitope (N-acetyl-D-galactosamine alpha-O-serine/threonine) density in primary breast carcinoma: a functional predictor of aggressiveness. Mol. Immunol. 26, 1–5. ( 10.1016/0161-5890(89)90013-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez JF, Lescar J, Chazalet V, Audfray A, Gagnon J, Alvarez R, Breton C, Imberty A, Mitchell EP. 2006. Biochemical and structural analysis of Helix pomatia agglutinin. A hexameric lectin with a novel fold. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20 171–20 180. ( 10.1074/jbc.M603452200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markiv A, Peiris D, Curley GP, Odell M, Dwek MV. 2011. Identification, cloning, characterization of two N-acetylgalactosamine-binding lectins from the albumen gland of Helix pomatia. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20 260–20 266. ( 10.1074/jbc.M110.184515) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rambaruth ND, Greenwell P, Dwek MV. 2012. The lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin recognizes O-GlcNAc containing glycoproteins in human breast cancer. Glycobiology 22, 839–848. ( 10.1093/glycob/cws051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saint-Guirons J, Zeqiraj E, Schumacher U, Greenwell P, Dwek M. 2007. Proteome analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer cells recognized by the lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA). Proteomics 7, 4082–4089. ( 10.1002/pmic.200700434) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peiris D, Ossondo M, Fry S, Loizidou M, Smith-Ravin J, Dwek MV. 2015. Identification of O-linked glycoproteins binding to the lectin Helix pomatia agglutinin as markers of metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 10, e0138345 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0138345) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welinder C, Jansson B, Ferno M, Olson H, Baldetorp B. 2009. Expression of Helix pomatia lectin binding glycoproteins in women with breast cancer in relationship to their blood group phenotypes. J. Proteome Res. 8, 782–787. ( 10.1021/pr800444b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fry SA, Sinclair J, Timms JF, Leathem AJ, Dwek MV. 2013. A targeted glycoproteomic approach identifies cadherin-5 as a novel biomarker of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 328, 335–344. ( 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streets AJ, Brooks SA, Dwek MV, Leathem AJ. 1996. Identification, purification and analysis of a 55 kDa lectin binding glycoprotein present in breast cancer tissue. Clin. Chim. Acta 254, 47–61. ( 10.1016/0009-8981(96)06363-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr MA. 1990. The structure and function of human IgA. Biochem. J. 271, 285–296. ( 10.1042/bj2710285) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woof JM, Mestecky J. 2005. Mucosal immunoglobulins. Immunol. Rev. 206, 64–82. ( 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00290.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woof JM. (ed.). 2007. The structure of IgA. In Mucosal immune defense: immunoglobulin A (ed. Kaetzel CS.), pp. 1–24. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novak J, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Renfrow MB. 2012. Glycosylation of IgA1 and pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 365–382. ( 10.1007/s00281-012-0306-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarelli E, Smith AC, Hendry BM, Challacombe SJ, Pouria S. 2004. Human serum IgA1 is substituted with up to six O-glycans as shown by matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Carbohydr. Res. 339, 2329–2335. ( 10.1016/j.carres.2004.07.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woof JM, Russell MW. 2011. Structure and function relationships in IgA. Mucosal Immunol. 4, 590–597. ( 10.1038/mi.2011.39) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi K, Smith AD, Poulsen K, Kilian M, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Novak J, Renfrow MB. 2012. Naturally occurring structural isomers in serum IgA1 o-glycosylation. J. Proteome Res. 11, 692–702. ( 10.1021/pr200608q) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak J, Renfrow MB, Gharavi AG, Julian BA. 2013. Pathogenesis of immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 22, 287–294. ( 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835fef54) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattu TS, Pleass RJ, Willis AC, Kilian M, Wormald MR, Lellouch AC, Rudd PM, Woof JM, Dwek RA. 1998. The glycosylation and structure of human serum IgA1, Fab, Fc regions and the role of N-glycosylation on Fcalpha receptor interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2260–2272. ( 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2260) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field MC, Amatayakul-Chantler S, Rademacher TW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. 1994. Structural analysis of the N-glycans from human immunoglobulin A1: comparison of normal human serum immunoglobulin A1 with that isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem. J. 299, 261–275. ( 10.1042/bj2990261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mestecky J, Tomana M, Crowley-Nowick PA, Moldoveanu Z, Julian BA, Jackson S. 1993. Defective galactosylation and clearance of IgA1 molecules as a possible etiopathogenic factor in IgA nephropathy. Contrib. Nephrol. 104, 172–182. ( 10.1159/000422410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coppo R, Amore A, Gianoglio B, Reyna A, Peruzzi L, Roccatello D, Alessi D, Sena LM. 1993. Serum IgA and macromolecular IgA reacting with mesangial matrix components. Contrib. Nephrol. 104, 162–171. ( 10.1159/000422409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen AC, Harper SJ, Feehally J. 1995. Galactosylation of N- and O-linked carbohydrate moieties of IgA1 and IgG in IgA nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 100, 470–474. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03724.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomana M, Matousovic K, Julian BA, Radl J, Konecny K, Mestecky J. 1997. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in sera of IgA nephropathy patients is present in complexes with IgG. Kidney Int. 52, 509–516. ( 10.1038/ki.1997.361) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomana M, Novak J, Julian BA, Matousovic K, Konecny K, Mestecky J. 1999. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 73–81. ( 10.1172/JCI5535) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiki Y, Iwase H, Saitoh M, Saitoh Y, Horii A, Hotta K, Kobayashi Y. 1996. Reactivity of glomerular and serum IgA1 to jacalin in IgA nephropathy. Nephron 72, 429–435. ( 10.1159/000188908) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novak J, et al. 2015. New insights into the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Dis. 1, 8–18. ( 10.1159/000382134) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen AC, Willis FR, Beattie TJ, Feehally J. 1998. Abnormal IgA glycosylation in Henoch-Schonlein purpura restricted to patients with clinical nephritis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 13, 930–934. ( 10.1093/ndt/13.4.930) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen AC, Bailey EM, Barratt J, Buck KS, Feehally J. 1999. Analysis of IgA1 O-glycans in IgA nephropathy by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Springer GF, Chandrasekaran EV, Desai PR, Tegtmeyer H. 1988. Blood group Tn-active macromolecules from human carcinomas and erythrocytes: characterization of and specific reactivity with mono- and poly-clonal anti-Tn antibodies induced by various immunogens. Carbohydr. Res. 178, 271–292. ( 10.1016/0008-6215(88)80118-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks SA, Dwek MV, Schumacher U. 2002. Functional and molecular glycobiology. Oxford, UK: Bios Scientific Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks SA, Carter TM, Royle L, Harvey DJ, Fry SA, Kinch C, Dwek RA, Rudd PM. 2008. Altered glycosylation of proteins in cancer: what is the potential for new anti-tumour strategies. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 8, 2–21. ( 10.2174/187152008783330860) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welinder C, Baldetorp B, Blixt O, Grabau D, Jansson B. 2013. Primary breast cancer tumours contain high amounts of IgA1 immunoglobulin: an immunohistochemical analysis of a possible carrier of the tumour-associated Tn antigen. PLoS ONE 8, e61749 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0061749) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swann R, et al. 2013. The DietCompLyf study: a prospective cohort study of breast cancer survival and phytoestrogen consumption. Maturitas 75, 232–240. ( 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.03.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685. ( 10.1038/227680a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutton-Smith M, Dell A. 2006. Analysis of carbohydrates/glycoproteins by MS. In Cell biology: a laboratory handbook (ed. Cellis JE.), pp. 415–425. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonopoulos A, Demotte N, Stroobant V, Haslam SM, van der Bruggen P, Dell A.. 2012. Loss of effector function of human cytolytic T lymphocytes is accompanied by major alterations in N- and O-glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11 240–11 251. ( 10.1074/jbc.M111.320820) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ceroni A, Maass K, Geyer H, Geyer R, Dell A, Haslam SM. 2008. GlycoWorkbench: a tool for the computer-assisted annotation of mass spectra of glycans. J. Proteome Res. 7, 1650–1659. ( 10.1021/pr7008252) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vijayakumar T, Ankathil R, Remani P, Sasidharan VK, Vijayan KK, Vasudevan DM. 1986. Serum immunoglobulins in patients with carcinoma of the oral cavity, uterine cervix and breast. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 22, 76–79. ( 10.1007/BF00205721) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saxena SP, Mishra VK, Basu PK, Prakash O, Sharma SP. 1993. Significance of serum immunoglobulin levels in conglomeration with trans-sternal phlebography in the phlebography management of breast cancer. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 36, 21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad S, Faruqi NA, Arif SH, Akhtar S. 2002. Serum immunoglobulin levels in neoplastic disorder of breast. J. Indian. Med. Assoc. 100, 495–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ali HQ, Mahdi NK, Al-Jowher MH. 2012. Serum Ig and cytokine levels in women with breast cancer before and after mastectomy. Med. J. Islamic World Acad. Sci. 20, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varki A, Kannagi R, Toole BP. 2009. Glycosylation changes in cancer. In Essentials of glycobiology (eds Varki A, et al.). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gulsvik A, Fagerhoi MK. 1979. Smoking and immunoglobulin levels. Lancet 1, 449 ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)90934-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McMillan SA, Douglas JP, Archbold GP, McCrum EE, Evans AE. 1997. Effect of low to moderate levels of smoking and alcohol consumption on serum immunoglobulin concentrations. J. Clin. Pathol. 50, 819–822. ( 10.1136/jcp.50.10.819) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Standish LJ, Sweet ES, Novack J, Wenner CA, Bridge C, Nelson A, Martzen M, Torkelson C. 2008. Breast cancer and the immune system. J. Soc. Integr. Oncol. 6, 158–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.York WS, Ranzinger R. 2012. MIRAGE: Minimum information required for a glycomics experiment. In Glyco-Bioinformatics: 2nd international Beilstein symposium on glyco-bioinformatics—cracking the sugar code by navigating the glycospace (eds Hicks MG, Kettner C.). Berlin, Germany: Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Leoz ML, Young LJ, An HJ, Kronewitter SR, Kim J, Miyamoto S, Borowsky AD, Chew HK, Lebrilla CB.. 2011. High-mannose glycans are elevated during breast cancer progression. Mol. Cell Proteomics 10, M110.002717 ( 10.1074/mcp.M110.002717) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adamczyk B, Tharmalingam T, Rudd PM. 2012. Glycans as cancer biomarkers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1347–1353. ( 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haakensen VD, Steinfeld I, Saldova R, Shehni AA, Kifer I, Naume B, Rudd PM, Borresen-Dale AL, Yakhini Z. 2016. Serum N-glycan analysis in breast cancer patients—relation to tumour biology and clinical outcome. Mol. Oncol. 10, 59–72. ( 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ju L, Wang Y, Xie Q, Xu X, Li Y, Chen Z, Li Y. 2016. Elevated level of serum glycoprotein bifucosylation and prognostic value in Chinese breast cancer. Glycobiology 26, 460–471. ( 10.1093/glycob/cwv117) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fry SA, Afrough B, Lomax-Browne HJ, Timms JF, Velentzis LS, Leathem AJ. 2011. Lectin microarray profiling of metastatic breast cancers. Glycobiology 21, 1060–1070. ( 10.1093/glycob/cwr045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kronewitter SR, De Leoz ML, Strum JS, An HJ, Dimapasoc LM, Guerrero A, Miyamoto S, Lebrilla CB, Leiserowitz GS.. 2012. The glycolyzer: automated glycan annotation software for high performance mass spectrometry and its application to ovarian cancer glycan biomarker discovery. Proteomics 12, 2523–2538. ( 10.1002/pmic.201100273) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruhaak LR, Kim K, Stroble C, Taylor SL, Hong Q, Miyamoto S, Lebrilla CB, Leiserowitz G. 2016. Protein-specific differential glycosylation of immunoglobulins in serum of ovarian cancer patients. J. Proteome Res. 15, 1002–1010. ( 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joshi M, Patil R. 2010. Estimation and comparative study of serum total sialic acid levels as tumor markers in oral cancer and precancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 6, 263–266. ( 10.4103/0973-1482.73339) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alley WR Jr, Novotny MV. 2010. Glycomic analysis of sialic acid linkages in glycans derived from blood serum glycoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 9, 3062–3072. ( 10.1021/pr901210r) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saldova R, et al. 2014. Association of N-glycosylation with breast carcinoma and systemic features using high-resolution quantitative UPLC. J. Proteome Res. 13, 2314–2327. ( 10.1021/pr401092y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawaguchi-Sakita N, et al. 2016. Serum immunoglobulin G Fc region N-glycosylation profiling by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry can distinguish breast cancer patients from cancer-free controls. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 469, 1140–1145. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.114) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yanagawa H, et al. 2014. A panel of serum biomarkers differentiates IgA nephropathy from other renal diseases. PLoS ONE 9, e98081 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0098081) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berthelot L, et al. 2015. Recurrent IgA nephropathy is predicted by altered glycosylated IgA, autoantibodies and soluble CD89 complexes. Kidney Int. 88, 815–822. ( 10.1038/ki.2015.158) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alsabti EA. 1979. Serum immunoglobulins in breast cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 11, 129–133. ( 10.1002/jso.2930110206) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset is provided in the electronic supplementary material.