Abstract

Policy and financial pressures have driven up use of observation stays for patients in traditional Medicare and the Veterans’ Affairs Healthcare System. Using claims data (2004-2014) from OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse, we examined whether people in private Medicare Advantage (MA) and commercial plans experienced similar changes. We found that use of observation increased rapidly for patients in MA plans—even though MA plans were not subject to the same pressures as government-run programs. In contrast, use of observation remained constant for people in commercial plans—except for enrollees 65 and older, for whom it increased somewhat. Privately insured patients returning to the hospital after an inpatient stay were increasingly likely to be placed under observation. Our results suggest that observation is rapidly replacing inpatient admissions and readmissions for many older patients in MA and commercial plans, while younger patients continue to be admitted as inpatients at relatively constant rates.

Keywords: observation status, medicare advantage, divergent trends, readmission substitute, age-based disposition

Introduction

Some patients require a period of observation care—usually delivered in an outpatient setting—that allows doctors to monitor them to determine if they should be admitted to the hospital or return home. Approximately 2.5 million people are placed in observation each year (Venkatesh et al., 2011; Wiler, Ross, & Ginde, 2011), which could have implications for the cost and quality of care they receive (Institute of Medicine, 2007; Jagminas & Partridge, 2005; Lind, Noel-Miller, Zhao, & Schur, 2015; McDermott et al., 1997; Ross et al., 2007).

Several studies have shown a rapid increase in the use of observation stays among patients enrolled in government-run health care plans, such as traditional Medicare and the Veterans’ Affairs (VA) Healthcare System (Wright et al., 2015). One study found that the number of observation stays by traditional Medicare patients more than doubled from 2001 to 2009, with the greatest increase occurring in cases not leading to an inpatient admission (Zhao, Schur, Kowlessar, & Lind, 2013). Another study found that for traditional Medicare patients aged 65 years and older, the number of claims for observation services increased by 26% from 2007 to 2009 (Feng, Wright, & Mor, 2012). Observation stays lasting 2 or more days are especially more common among people in government-run health plans, despite national guidelines specifying that such stays rarely should exceed 24 hours (American College of Emergency Physicians, 2015; Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], Outpatient Observation Services, 2012). Hospitals may be substituting outpatient observation stays for inpatient admission and readmission—both of which have become less common over time in both traditional Medicare and the VA system (Feng et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2013).

New Contributions

Unlike most previous research (Overman, Freburger, Assimon, Li, & Brookhart, 2014), our study examined changes in the use of observation status among people enrolled in private plans—that is, enrollees in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans and non-Medicare commercial and employer plans (commercial plans). We hypothesized that patients in private plans would be less likely to experience pressures that have driven up the use of observation status for traditional Medicare and VA patients. Instead, we found that patients in MA plans experienced similar increases in frequency of observation use as those in government-run health care plans. In contrast, use of observation remained constant for people aged 18 to 64 years enrolled in commercial plans.

Study Data and Method

We conducted a retrospective analysis using deidentified1 administrative claims data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse, a database that includes medical and eligibility information for over 150 million MA and commercial enrollees (Wallace, Shah, Dennen, Bleicher, & Crown, 2014). These data contain claims from individuals throughout the United States, with the greatest representation in the South and Midwest U.S. Census regions.2 Our database did not include Medicare fee-for-service, Medicare supplemental, or other secondary insurance claims.

We examined MA enrollees’ observation stays for 11 years by using claims with dates of service between January 2004 and December 2014. For the commercially insured, we had complete information only from August 2005 through December 2014. Therefore, we included only commercial claims for services that took place during that period.

For each month, we identified all enrollees aged 18 years and older with primary medical coverage at the start of their hospital visit. Like other studies of observation patients, we excluded data for MA enrollees younger than 65 years—who qualify for Medicare because they are disabled—because changes in the Social Security Disability Insurance program strongly affected the composition of this population during the study years (Autor & Duggan, 2006; Daly, Lucking, & Schwabish, 2013; Duggan & Imberman, 2009). We identified a monthly average of 15.3 million MA and commercial enrollees from August 2005 to December 2014.

Observation Versus Inpatient Admission

We identified all individuals who had an observation stay by using a combination of revenue codes (0760, 0762) or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT-4) codes (99217, 99218, 99219, 99220, 99224, 99225, 99226, 99234, 99235, 99236). We excluded patients admitted as inpatients immediately following an observation stay (fewer than 6% of observation patients in any given year). This ensures that our results are comparable to findings from prior studies that similarly excluded such patients (Feng et al., 2012; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2010; Sheehy et al., 2013). For enrollees with more than one observation stay during a month, we included all stays in the analysis. For each observation stay, we generated the length of stay in days. Our total analytical sample consisted of about 3.5 million observation claims—averaging about 30,000 monthly observation stays.

For the inpatient cohort, we included all inpatient stays lasting up to 2 days. If an enrollee had several short inpatient stays during the month, we included all stays. We identified about 4.4 million claims (averaging about 38,000 per month) of these short-term inpatient stays.

Trends

We calculated monthly rates of observation stays and short-term inpatient stays separately for enrollees in MA and commercial plans using the number of visits as the numerator and the total number of enrollees as the denominator. We report rates as number of visits per 1,000 enrollees.

Readmissions

We conducted further analyses that focused on inpatient readmission and return observation stays. First, for each month between August 2005 and December 2014, we identified all inpatient admissions. Among these index inpatient stays, we identified those with at least one subsequent inpatient admission and those with at least one subsequent observation stay within 30 days of initial discharge. We then calculated monthly readmission rates and return observation rates using the total number of index admissions as the denominator and the number of index admissions followed by at least one readmission or return observation stay as the numerator.

Subsequently, we identified unplanned inpatient claims following the methodology used by the CMS (2014) for the top third of hospitals with the largest drop in readmission between January 2009 and December 2014. For each of these index inpatient stays, we identified subsequent readmissions and observation stays that occurred within 30 days of leaving the hospital. For each hospital, we then computed the share of index inpatient stays that resulted in a readmission or an observation stay. We report the weighted averages of these shares, where the weights are the hospital’s total number of index admissions.

Study Results

Of people who experienced an observation stay, 82% were enrolled in a commercial plan and, of these enrollees, 95% were younger than 65 years. Of people who experienced an inpatient stay of 2 days or less, 84% were enrolled in a commercial plan and, of these enrollees, 95% were younger than 65 years. MA enrollees aged 65 years and older experienced 18% of observation stays and 16% of short inpatient stays.

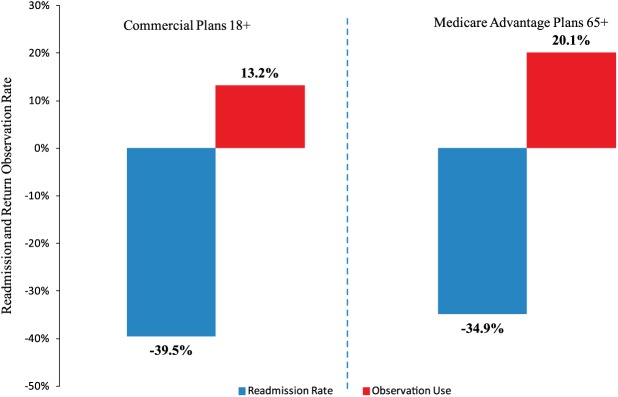

Figure 1 shows that between August 2005 and December 2014, observation stays were considerably more common among patients in MA plans than for those in commercial plans. The data also reveal that patients enrolled in MA plans were more than twice as likely (+133%, p < .01) to be under observation in 2014 as they were 11 years earlier in 2004. Observation rates for MA plan enrollees remained stable from 2004 to 2006 (about 2.5 per 1,000) but saw an inflection point in late 2006, from which time the rate increased steeply to about 6.3 per 1,000. This “hockey stick” pattern suggests that important changes occurred starting in 2006, which produced a substantial increase in the use of observation over the following 7 years.

Figure 1.

Monthly observation rate among Medicare Advantage (MA) plan enrollees (2004-2014) and commercial plan enrollees (August 2005-December 2014).

Source. Authors’ analysis of data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse.

In contrast, among commercial plan patients 18 years and older, the use of observation remained relatively stable between 2005 and 2014, increasing by only 8 percentage points (p < .01) during that period.

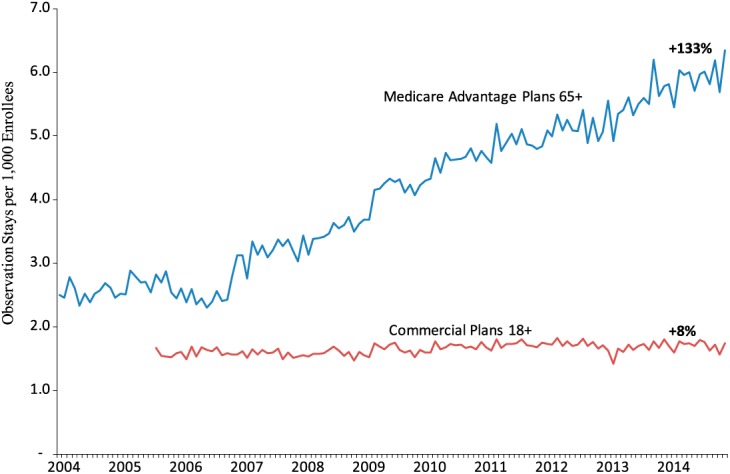

Figure 2 shows monthly rates of observation stays for commercial plans by the enrollee’s age category. Commercial plan members aged 65 years and older (still employed) became somewhat more likely to be placed under observation between August 2005 and December 2014 (+33%, p < .01). However, they began experiencing this increase later than people enrolled in MA plans, and observation rates crept up only gradually from late 2005 through 2009. In early 2010, the climb in observation rates for commercial plan enrollees aged 65 years and older began accelerating, increasing 27% (p < .01) over the following 5 years. By contrast, observation rates for adults younger than 65 years in commercial plans remained relatively constant between 2005 and 2014, increasing by only 6% (p < .01) between 2005 and 2014.

Figure 2.

Monthly observation rate among commercial plan enrollees by age (August 2005-December 2014).

Source. Authors’ analysis of data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse.

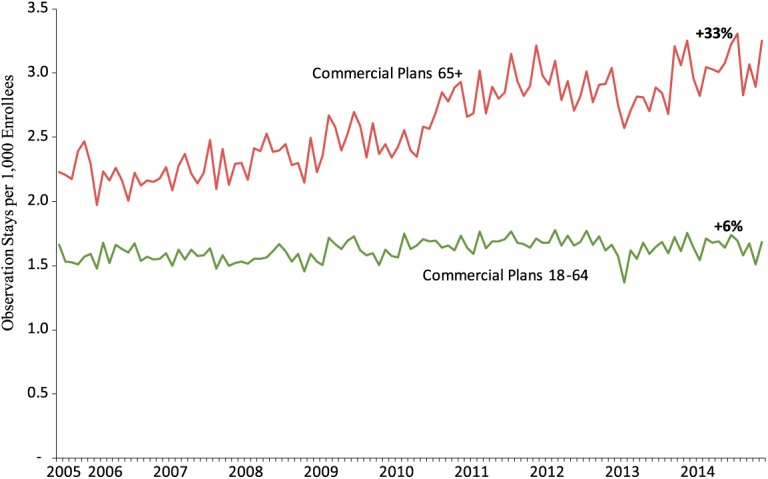

Privately insured patients in both MA and commercial plans were placed under observation for much longer periods in 2014 than in 20063 (Figure 3). In 2014, 20.1% of those in commercial plans stayed in observation for at least 2 days, compared with 10.1% 8 years earlier—which represents an increase of 99% (p < .01). During this period, the share of patients enrolled in MA plans who were placed under observation for 2 days or more leapt by 327% (from 4.5% to 19.2%, p < .01).

Figure 3.

Number of days spent under observation by private plan enrollees in 2006 and 2014.

Source. Authors’ analysis of data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse.

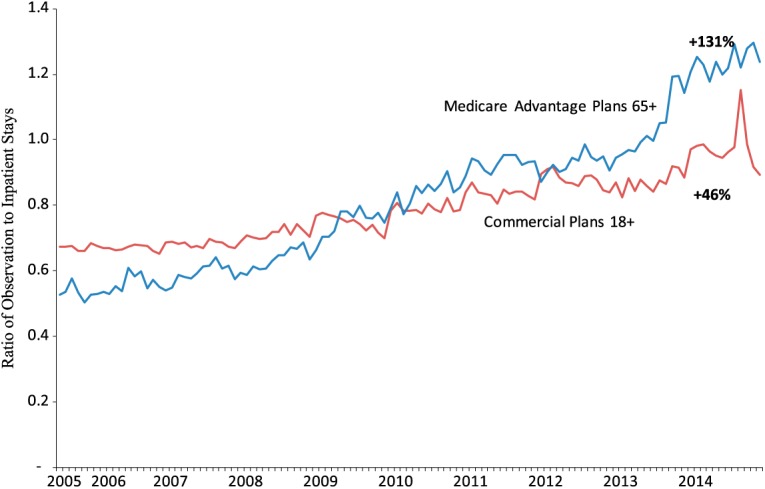

MA plan enrollee admissions for short inpatient stays were stable, decreasing less than 0.5% per year from August 2005 through December 2014 (data available on request from the corresponding author). On the other hand, people in commercial plans became less likely to be admitted for a short inpatient stay (−25%) during this period. Consequently, the ratio of observation stays to short inpatient stays increased by 46% for commercial plan patients and by 131% for those in MA plans (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ratio of observation to short inpatient stays for private plan enrollees (August 2005-December 2014).

Source. Authors’ analysis of data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse.

We found a slight decrease in 30-day readmission rates from August 2005 through December 2014, for both patients in commercial plans (−11%) and those in MA plans (−12%; data available on request from the corresponding author). In contrast, the share of privately insured patients who were placed under observation when they returned to a hospital within 30 days after an inpatient stay grew rapidly, especially for MA plan enrollees (+117%).

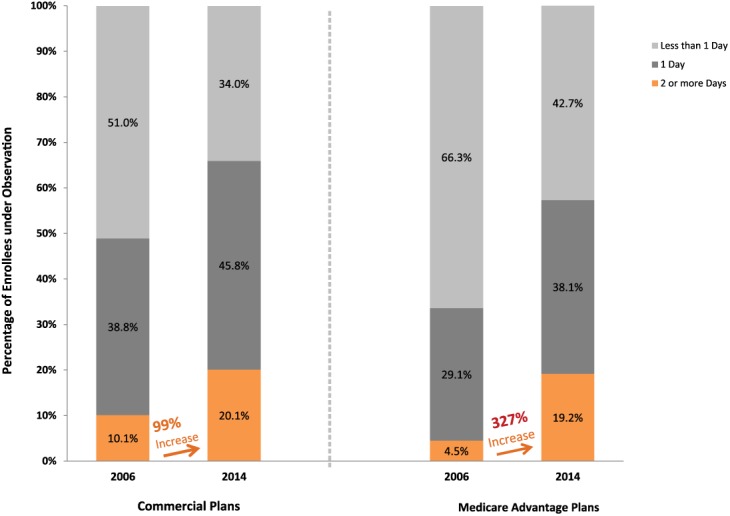

These diverging trends were particularly pronounced for some hospitals that experienced large drops in readmission rates between 2009 and 2014 (Figure 5). For example, the top one third of hospitals with the largest drop in readmitted MA plan patients aged 65 years and older (−34.9%) also placed significantly more of their returning patients under observation (+20.1%).

Figure 5.

Changes in readmission and return observation rates within 30 days of discharge for private plan enrollees at the top 33% of hospitals with the largest drop in readmissions (2009-2014).

Source. Authors’ analysis of data from the OptumLabs™ Data Warehouse.

Discussion

Our study found that people aged 65 years and older enrolled in MA plans were increasingly likely to be placed under observation between 2004 and 2014. The use of observation also increased among commercial plan enrollees aged 65 years and older, but this increase occurred later and was less pronounced than the increase in observation use for MA plan enrollees. These trends are comparable to the experience of patients in traditional Medicare and the VA Healthcare System (Wright et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2013). In contrast, the use of observation stays remained largely unchanged for patients aged 18 to 64 years in commercial plans. We also found a notable increase in the duration of MA and commercial enrollees’ observation stays.

For each short inpatient admission that took place during the study period, there was an increased number of observation stays. Enrollees who were initially admitted as inpatients and subsequently returned to the hospital were more likely to be placed under observation rather than be readmitted as inpatients. Conversely, inpatient readmission rates declined.

The nearly parallel lines for observation rates prior to 2007 suggest that people in MA and commercial plans with similar clinical characteristics received care in similar hospital settings up to that point. Our study did not examine whether the quality of care differed between these settings. However, the rapid subsequent rise in the observation rate for MA plan enrollees aged 65 years and older suggests that, starting in late 2006, growth in the use of observation status for these patients was driven by factors—probably nonclinical in nature—above and beyond underlying trends related to age and health status (Zhao et al., 2013). These divergent trends suggest a degree of differentiation by patient’s age may be entering into decisions about patient disposition within hospitals.

As discussed in previous studies, a number of factors may be driving these divergent trends in the use of observation versus inpatient admission and readmission, including increased scrutiny of short inpatient stays (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2010), penalties for hospitals with high rates of avoidable readmission (CMS, 2013), efficiency advantages of observation stays (more rapid triage of patients and lower hospital cost), and lower out-of-pocket costs for patients placed under outpatient observation rather than admitted as inpatients.4

Starting in 2005 and continuing through 2014, CMS made several changes to Medicare reimbursement rules that encouraged the use of observation status. Also starting in 2005 with demonstrations in six states, recovery audit contractors began identifying and recovering improper payments to Medicare fee-for-service providers. The recovery audit contractor program was expanded nationwide in 2010. Many of these audits resulted in complete denial of claims for short inpatient stays. As a result, hospitals were encouraged to shift patients to outpatient observation rather than admit them for short inpatients stays. In 2012, CMS began imposing fines on hospitals with excess avoidable readmissions; these fines tend to encourage hospitals to hold patients in outpatient observation. Because of these nonclinical factors, patients who might have previously been admitted or readmitted as inpatients may have been labeled as observation patients (Feng et al., 2012; Noel-Miller & Lind, 2015; Overman et al., 2014).

However, it is important to note that some of the likely reasons behind the increased use of observation status, including scrutiny of short inpatient stays and readmission penalties, apply primarily to traditional Medicare. Increases in observation stays for MA plan patients could represent a spillover effect from incentives related to traditional Medicare patients. For instance, to avoid audits and payment penalties, physicians may assume that all older patients should be treated as if they were traditional Medicare patients.

Assuming that the observation rate for people in MA plans had remained at the 2004 level, the rate of short inpatient stays would likely have been 62% higher than the rate we observed in 2014. Similarly, if observation rates for returning MA plan patients had held steady at the 2005 level, the 30-day readmission rate would likely have increased by as much as 1.5% instead of falling by 11.6% from 2005 to 2014.

We are not arguing that rising observation rates entirely account for the decline in inpatient admission and readmission rates. Rather, our findings suggest that declines in inpatient use might have been less pronounced in the absence of growth in the use of observation stays.

In addition, the accelerating trend in the use of observation for commercial patients aged 65 years and older starting in 2009 suggests a further diffusion in the growth of observation experienced by traditional Medicare and MA plan patients, with observation possibly becoming a substitute for inpatient admission and readmission.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that older patients may be receiving care in a different hospital setting (i.e., outpatient vs. inpatient) than younger patients for nonclinical reasons—suggesting differential disposition based on the patient’s age. Our study also suggests that declining readmission rates may not be an adequate measure of hospitals’ success in reducing medical complications or improving the quality of care for either inpatients or outpatients. Although a recent study did not find evidence that readmission penalties were causing hospitals to substitute observation stays for inpatient readmission among traditional Medicare patients (Zuckerman, Sheingold, Orav, Ruhter, & Epstein, 2016), tying penalties to readmission rates may allow some hospitals to avoid penalties by simply labeling returning patients as outpatients rather than by improving care (Himmelstein & Woolhandler, 2015). Finally, our findings raise questions about the appropriateness of the choice of care setting (outpatient vs. inpatient) and how this choice affects quality of care and patient out-of-pocket costs. These questions deserve further research and scrutiny.

All study data were deidentified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Our study was exempt from approval by an institutional review board as we used preexisting, deidentified data.

Southern and Midwestern states are overrepresented in the data. See OptumLabs™ (2014).

We used 2006 because it was the first year with 12 months of data for both MA and commercial claims.

Despite a common perception that patients under outpatient observation pay more out of pocket than they would if they had been admitted as inpatients, the vast majority of traditional Medicare and VA patients who are placed under observation pay less than if they had been admitted (Lind et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2015).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American College of Emergency Physicians. (2015). Emergency department observation services. Retrieved from https://www.acep.org/Clinical—Practice-Management/Emergency-Department-Observation-Services/

- Autor D. H., Duggan M. G. (2006). The growth in Social Security Disability rolls: A fiscal crisis unfolding (Working Paper No. 12436). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w12436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2013). Readmissions reduction program. Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2014). Planned readmission algorithm (Version 3.0). Baltimore, MD: Author; Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html [Google Scholar]

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Outpatient Observation Services. (2012). Medicare claims processing manual: Chapter 4-Part B hospital (Including inpatient hospital Part B and OPPS). Baltimore, MD: Author; Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads//clm104c04.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Daly M. C., Lucking B., Schwabish J. A. (2013). The future of Social Security Disability Insurance (Economic Letter 2013-17). San Francisco, CA: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; Retrieved from http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2013/june/future-social-security-disability-insurance-ssdi/ [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M., Imberman S. A. (2009). Why are the disability rolls skyrocketing? The contribution of population characteristics, economic conditions, and program generosity. In Cutler D. M., Wise D. A. (Eds.), Health at older ages: The causes and consequences of declining disability among the elderly (pp. 337-379). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Wright B., Mor V. (2012). Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Affairs, 31, 1251-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein D., Woolhandler S. (2015, August 27). Quality improvement: “Become good at cheating and you never need to become good at anything else.” Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/08/27/quality-improvement-become-good-at-cheating-and-you-never-need-to-become-good-at-anything-else/

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Hospital-based emergency care: At the breaking point. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jagminas L., Partridge R. A. (2005). Comparison of emergency department versus inhospital chest pain observation units. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23, 111-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind K. D., Noel-Miller C. M., Zhao L., Schur C. (2015). Observation status: Financial implications for Medicare beneficiaries. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/Hosp%20Obs%20Financial%20Impact%20Paper.pdf

- McDermott M. F., Murphy D. G., Zalenski R. J., Rydman R. J., McCarren M., Marden D., . . . Kampe L. (1997). A comparison between emergency diagnostic and treatment unit and inpatient care in the management of acute asthma. Archives of Internal Medicine, 157, 2055-2062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2010). Public meeting, September 13, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.medpac.gov/-public-meetings-/meetingdetails/september-2010-public-meeting

- Noel-Miller C., Lind K. (2015, October 28). Is observation status substituting for hospital readmission? Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/10/28/is-observation-status-substituting-for-hospital-readmission/

- OptumLabs™. (2014). Core U.S. data assets. Retrieved from https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/5302_Data_Assets_Chart_Sheet_ISPOR.pdf

- Overman R. A., Freburger J. K., Assimon M. M., Li X., Brookhart M. A. (2014). Observation stays in administrative claims databases: Underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety, 23, 902-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. A., Compton S., Medado P., Fitzgerald M., Kilanowski P., O’Neil B. J. (2007). An emergency department diagnostic protocol for patients with transient ischemic attack: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 50, 109-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy A. M., Graf B., Gangireddy S., Hoffman R., Ehlenbach M., Heidke C., . . . Jacobs E. A. (2013). Hospitalized but not admitted: Characteristics of patients with “observation status” at an academic medical center. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173, 1991-1998. Retrieved from http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1710122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh A. K., Geisler B. P., Gibson Chambers J. J., Baugh C. W., Bohan S., Schuur J. D. (2011). Use of observation care in U.S. emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS ONE, 6(9), 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace P. J., Shah N. D., Dennen T., Bleicher P. A., Crown W. H. (2014). Optum Labs: Building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Affairs, 33, 1187-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiler J. L., Ross M. A., Ginde A. A. (2011). National study of emergency department observation services. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18, 959-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright B., O’Shea A. M. J., Ayyagari P., Ugwi P. G., Kaboli P., Sarrazin M. V. (2015). Observation rates at veterans’ hospitals more than doubled during 2005–13, similar to Medicare trends. Health Affairs, 34, 1730-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Schur C., Kowlessar N., Lind K. D. (2013). Rapid growth in Medicare hospital observation services: What’s going on? Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/2013/rapid-growth-in-medicare-hospital-observation-services-AARP-ppi-health.pdf

- Zuckerman R. B., Sheingold S. H., Orav E. J., Ruhter J., Epstein A. M. (2016). Readmission, observation, and the hospital readmission reduction program. New England Journal of Medicine, 374, 1543-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]