Abstract

Since the initial description of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) in 1994, increasingly more cases of FFA have been reported in literature. Although clear epidemiologic data on the incidence and prevalence of FFA is not available, it is intriguing to consider whether FFA should be labeled as an emerging epidemic. A medline trend analysis as well as literature review using keywords “alopecia,” “hair loss,” and “cicatrical” were performed. Medline trend analysis of published FFA papers from 1905 to 2016 showed that the number of publications referenced in Medline increased from 1 (0.229%) in 1994 to 44 (3.5%) in 2016. The number of patients per published cohort also increased dramatically since the first report of FFA. Over the time period of January 2006–2016, our multi hair-referral centers collaboration study also showed a significant increase in new diagnoses of FFA. At this juncture, the cause for the rapid rise in cases is one of speculation. It is plausible that a cumulative environmental or toxic factor may trigger hair loss in FFA. Once perhaps a “rare type” of cicatricial alopecia, FFA is now being seen in a frequency in excess of what is expected, thus suggestive of an emerging epidemic.

Keywords: Frontal fibrosing alopecia, Scarring alopecia, Epidemic

Introduction

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a type of primary cicatricial alopecia characterized by a distinctive clinical pattern of progressive recession of the frontal/temporal hairline in a band-like distribution often associated with loss of eyebrows. Histologically there is lymphocytic inflammation surrounding the isthmus of the hair follicle, which can lead to permanent follicular damage. FFA was first described by Australian dermatologist Kossard in 1994 in 6 postmenopausal women, and it was thought to be a variant of lichen planopilaris [1]. The clinical spectrum of FFA has been expanded to include loss of hair in the occipital scalp, as well as loss of eyelashes, facial, and body hair [2]. Facial papules and lichenoid pigmentary alterations have also been noted suggesting that the inflammatory process may be systemic and not limited to the scalp. Since the initial description, cases have been reported in premenopausal women as well as in men and there has been a dramatic increase of cases reported worldwide. Although clear epidemiologic data on the incidence and prevalence of FFA is not available, it is intriguing to consider whether FFA should be labeled as an emerging epidemic. If so, identifying and eliminating potential risks or triggering factors could make a significant impact in decreasing the incidence of disease.

What is an Emerging Epidemic?

The origin of the word epidemic derives from the Greek “epi” upon and “demos” the people (oxford dictionary online) and refers to an increase of an illness in excess of what is normally expected or what has been seen previously [3]. An epidemic does not necessarily refer to a communicable disease and can be used when describing increased cases of breast cancer, obesity, or behavioral issues among others [3]. An emerging epidemic refers to a condition that has newly appeared in a population or one that has existed previously but has rapidly increased in incidence or geographic range [4].

What is the Evidence That FFA Is an Emerging Epidemic?

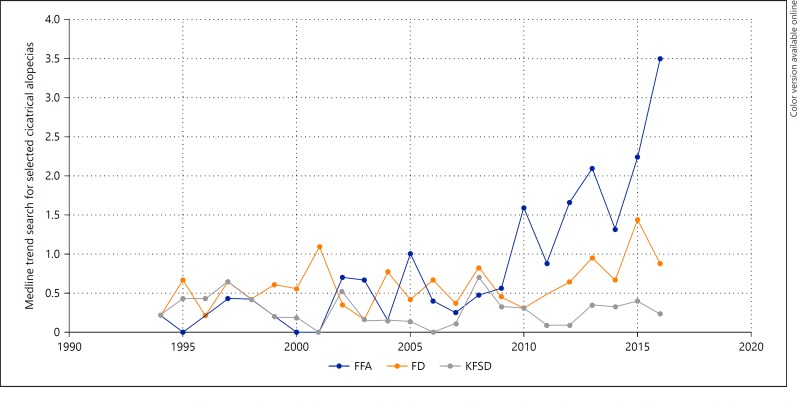

Medline Trends

Medline (PubMed) trend analysis, which calculates the total number and percentage of papers published in the medical literature for a particular subject, is one tool which can be used to analyze emerging epidemics. A trend analysis of published papers from 1905 to 2016 shows no reports of FFA prior to 1994. The number of publications referenced in Medline increased from 1 (0.229%) in 1994 to 44 (3.5%) in 2016 (Fig. 1). This is in contrast to other types of cicatricial alopecia with distinctive, searchable names such as folliculitis decalvans and keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans, which did not have similar increases in number or percentages of published papers over the same time period (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Medline Trend Search (1994–2016): the horizontal axis indicates the year of publication and the vertical axis indicates the percentage of publications referenced in Medline with regards to each of 3 diseases. FFA, frontal fibrosing alopecia; FD, folliculitis decalvans; KFSD, keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans.

Increases in Cohort Size

Most notable however is the dramatic increase in the number of patients reported in each of these FFA publications. As mentioned previously, the initial description of FFA in 1994 was of 6 women. In 1997, this cohort was expanded upon and 10 more patients from Australia (total of 16) were characterized. Other reports up until 1999 were of single cases or of small cohorts. In 2010, a cohort of 36 patients was reported [5] and then in 2013, 355 patients were reported in the largest cohort to date from Spain [6].

Increased Geographic Representation

Further evidence that FFA is an emerging epidemic is the increase in geographic range of cases being reported. Patients with FFA are not limited to first-world countries and have been reported in Australia, Northern and Southern America, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Increased Incidence and Prevalence in Hair Clinics

Is it possible that these increased reports are a result of better recognition as opposed to an actual increase in incidence? It is difficult to support this point of view. The clinical findings of band-like scarring alopecia in FFA and brow loss are distinctive and easy to be recognized by both hair specialists and general dermatologists. The first biopsy-proven patient with FFA at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Hair Disorders Clinic was seen in 2001. Despite being a high-volume tertiary referral site for hair disorders, the patient's “receding hairline” along with loss of eyebrows was not a pattern that was commonly seen. Indeed, the diagnosis of “the Australian” post-menopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia was so novel that the patient's case was presented at the UCSF dermatology grand rounds and later published in the Archives of Dermatology centerfold in 2003 [7]. Between 2003 and 2009, 36 cases were seen at UCSF and reported in the British Journal of Dermatology [5]. In 2016, more than 20 years since the initial description of FFA, the number of patients with this diagnosis typically exceeds the other types of cicatricial alopecia seen in the UCSF Hair Disorders Clinic, and on occasion even exceeds the number of patients with non-cicatricial alopecia. Over the time period of January 2006–2016, 98 patients with a new diagnosis of FFA were seen at the Hair Disorders Clinic at Kaiser Permanente Medical Group in Northern California (P.M.).

A survey of other tertiary hair referral centers showed similar increases in numbers of new patients diagnosed with the condition (Table 1). Another center has also published a report of an increasing frequency of frontal fibrosing alopecia cases [8].

Table 1.

New diagnoses of frontal fibrosing alopecia in 4 different tertiary hair referral centers

| Kaiser Permanente (P.M.) | Boston University (L.G.) | Bologna (A.T.) | Baylor University (D.W.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | ||||

| 2001 | 1 | |||

| 2002 | NDA | 1 | ||

| 2003 | NDA | 3 | ||

| 2004 | NDA | 3 | ||

| 2005 | NDA | 1 | 3 | |

| 2006 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| 2007 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| 2008 | 2 | 6 | 9 | NDA |

| 2009 | 5 | 4 | 11 | NDA |

| 2010 | 11 | 5 | 8 | NDA |

| 2011 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 2012 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 18 |

| 2013 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 20 |

| 2014 | 18 | 16 | 12 | 17 |

| 2015 | 15 | 13 | 23 | 14 |

| 2016 | 8 | 16 | 13 | 20 |

NDA, no data available.

A Condition Seen in Excess of What Is Expected

Since FFA shares many clinical and histologic features with LPP and Graham Little Syndrome, could it have been “lumped in” with these other diagnoses prior to the description of FFA in 1994? This is a possibility and indeed it is still debated whether FFA is a subtype of LPP. It is possible that FFA was present prior to 1994, but it is unlikely that it was seen with enough frequency to be clearly identified and separately characterized. Once perhaps a “rare type” of cicatricial alopecia, it is now being seen in a frequency in excess of what is expected, thus suggestive of an emerging epidemic.

Conclusion

FFA is a type of primary cicatricial alopecia seen with increasing frequency worldwide with evidence suggesting that this condition is an emerging epidemic. At this juncture, the cause for the rapid rise in cases is one of speculation. It is plausible that a cumulative environmental [9] or toxic factor may trigger hair loss in FFA once a certain threshold is reached, and if so, this factor may have an affinity for the pilosebaceous follicle. It is also possible that genetic variances could increase susceptibility to potential precipitating factors. Further laboratory and epidemiologic studies of affected patients will be of value in determining the cause, instituting preventative measures, as well as furthering our treatment options for patients.

Statement of Ethics

The data for this study was collected without the use of any personal patient identifiers or was publicly available.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia. Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miteva M, Camacho I, Romanelli P, Tosti A. Acute hair loss on the limbs in frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinicopathological study of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:426–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green MS, Swartz T, Mayshar E, Lev B, Leventhal A, Slater PE, et al. When is an epidemic an epidemic? Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morse SS. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid0101.950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samrao A, Chew AL, Price V. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a clinical review of 36 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1296–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vano-Galvan S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcon C, Arias-Santiago S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Garnacho-Saucedo G, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirmirani P, McCalmont T, Price VH. Bandlike frontal hair loss in a 62-year-old woman. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1363–1368. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.10.1363-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia. Skin. Therapy Lett. 2016;21:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debroy Kidambi A, Dobson K, Holmes S, Carauna D, Del Marmol V, Vujovic A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia in men: an association with facial moisturizers and sunscreens. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:260–261. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]