Abstract

Background

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is vastly recommended as the first‐line analgesic for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. However, there has been controversy about this recommendation given recent studies have revealed small effects of paracetamol when compared with placebo. Nonetheless, past studies have not systematically reviewed and appraised the literature to investigate the effects of this drug on specific osteoarthritis sites, that is, hip or knee, or on the dose used.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of paracetamol compared with placebo in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, Web of Science, LILACS, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts to 3 October 2017, and ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) portal on 20 October 2017.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing paracetamol with placebo in adults with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Major outcomes were pain, function, quality of life, adverse events and withdrawals due to adverse events, serious adverse events, and abnormal liver function tests.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors used standard Cochrane methods to collect data, and assess risk of bias and quality of the evidence. For pooling purposes, we converted pain and physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index function) scores to a common 0 (no pain or disability) to 100 (worst possible pain or disability) scale.

Main results

We identified 10 randomised placebo‐controlled trials involving 3541 participants with hip or knee osteoarthritis. The paracetamol dose varied from 1.95 g/day to 4 g/day, and the majority of trials followed participants for three months only. Most trials did not clearly report randomisation and concealment methods and were at unclear risk of selection bias. Trials were at low risk of performance, detection, and reporting bias.

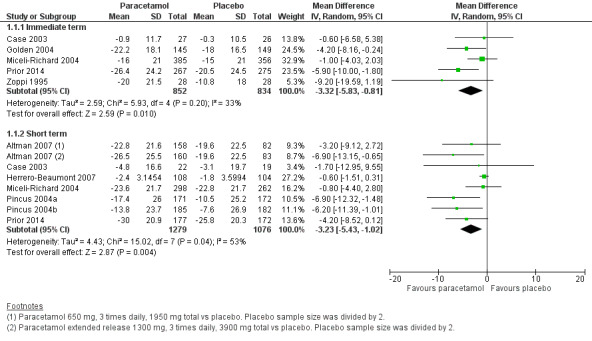

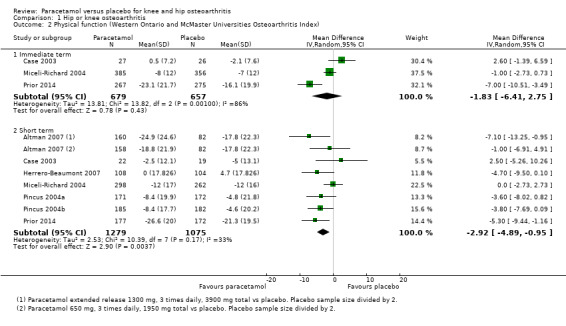

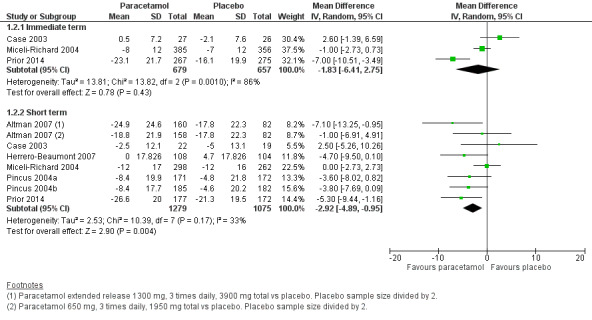

At 3 weeks' to 3 months' follow‐up, there was high‐quality evidence that paracetamol provided no clinically important improvements in pain and physical function. Mean reduction in pain was 23 points (0 to 100 scale, lower scores indicated less pain) with placebo and 3.23 points better (5.43 better to 1.02 better) with paracetamol, an absolute reduction of 3% (1% better to 5% better, minimal clinical important difference 9%) and relative reduction of 5% (2% better to 8% better) (seven trials, 2355 participants). Physical function improved by 12 points on a 0 to 100 scale (lower scores indicated better function) with placebo and was 2.9 points better (0.95 better to 4.89 better) with paracetamol, an absolute improvement of 3% (1% better to 5% better, minimal clinical important difference 10%) and relative improvement of 5% (2% better to 9% better) (7 trials, 2354 participants).

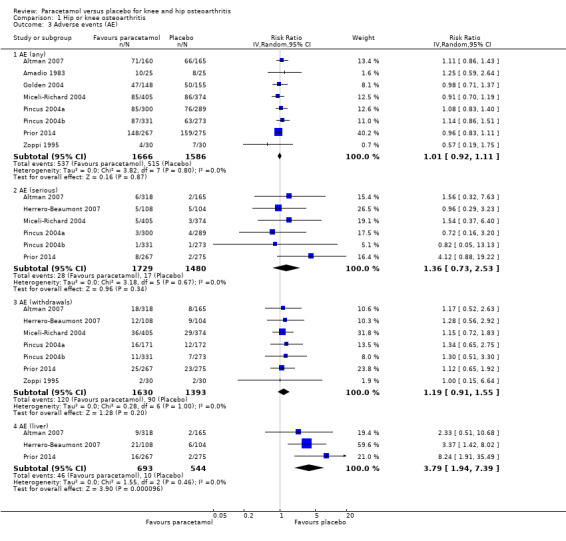

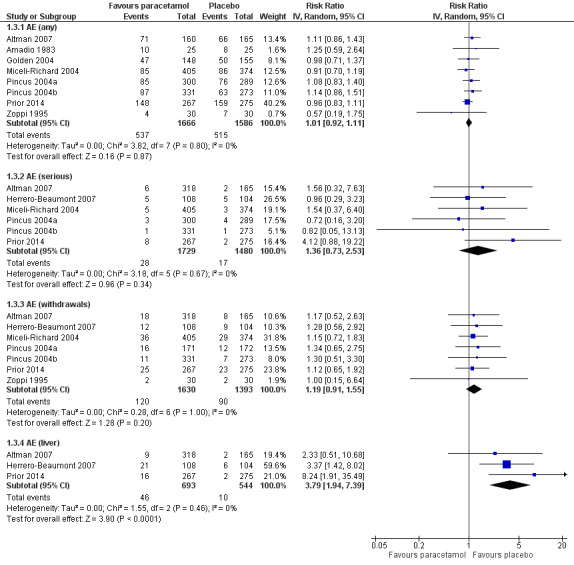

High‐quality evidence from eight trials indicated that the incidence of adverse events was similar between groups: 515/1586 (325 per 1000) in the placebo group versus 537/1666 (328 per 1000, range 299 to 360) in the paracetamol group (risk ratio (RR) 1.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 1.11). There was less certainty (moderate‐quality evidence) around the risk of serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, and the rate of abnormal liver function tests, due to wide CIs or small event rates, indicating imprecision. Seventeen of 1480 (11 per 1000) people treated with placebo and 28/1729 (16 per 1000, range 8 to 29) people treated with paracetamol experienced serious adverse events (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.53; 6 trials). The incidence of withdrawals due to adverse events was 65/1000 participants in with placebo and 77/1000 (range 59 to 100) participants with paracetamol (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.55; 7 trials). Abnormal liver function occurred in 18/1000 participants treated with placebo and 70/1000 participants treated with paracetamol (RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.94 to 7.39), but the clinical importance of this effect was uncertain. None of the trials reported quality of life.

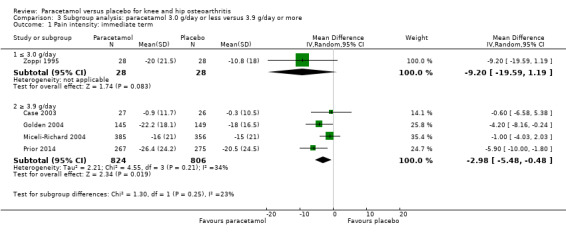

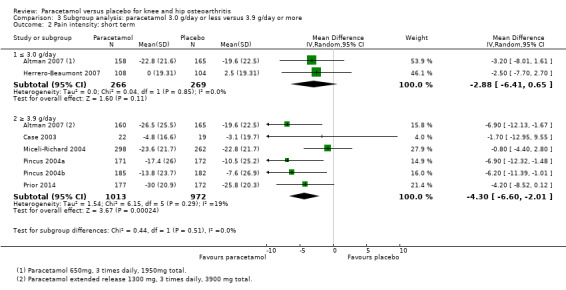

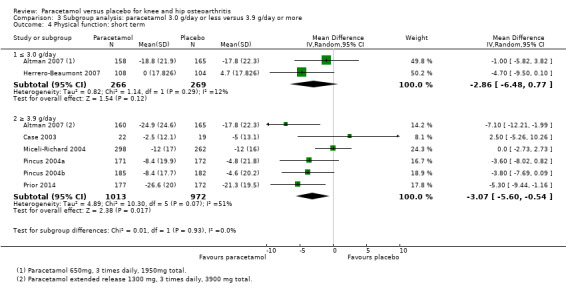

Subgroup analyses indicated that the effects of paracetamol on pain and function did not differ according to the dose of paracetamol (3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or greater).

Authors' conclusions

Based on high‐quality evidence this review confirms that paracetamol provides only minimal improvements in pain and function for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis, with no increased risk of adverse events overall. Subgroup analysis indicates that the effects on pain and function do not differ according to the dose of paracetamol. Due to the small number of events, we are less certain if paracetamol use increases the risk of serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, and rate of abnormal liver function tests.

Current clinical guidelines consistently recommend paracetamol as the first‐line analgesic medication for hip or knee osteoarthritis, given its low absolute frequency of substantive harm. However, our results call for reconsideration of these recommendations.

Keywords: Aged; Humans; Middle Aged; Acetaminophen; Acetaminophen/administration & dosage; Acetaminophen/adverse effects; Acetaminophen/therapeutic use; Analgesics, Non-Narcotic; Analgesics, Non-Narcotic/administration & dosage; Analgesics, Non-Narcotic/adverse effects; Analgesics, Non-Narcotic/therapeutic use; Arthralgia; Arthralgia/drug therapy; Arthralgia/etiology; Liver; Liver/drug effects; Osteoarthritis, Hip; Osteoarthritis, Hip/drug therapy; Osteoarthritis, Knee; Osteoarthritis, Knee/drug therapy; Pain Measurement; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Paracetamol for treating people with hip or knee osteoarthritis

Background

Osteoarthritis of the hip or knee is a progressive disabling disease affecting many people worldwide. Although paracetamol is widely used as a treatment option for this condition, recent studies have called into question how effective this pain relief medication is.

Search date

This review includes all trials published up to 3 October 2017.

Study characteristics

We included randomised clinical trials (where people are randomly put into one of two treatment groups) looking at the effects of paracetamol for people with hip or knee pain due to osteoarthritis against a placebo (a 'sugar tablet' that contains nothing that could act as a medicine). We found 10 trials with 3541 participants. On average, participants in the study were aged between 55 and 70 years, and most presented with knee osteoarthritis. The treatment dose ranged from 1.95 g/day to 4 g/day of paracetamol and participants were followed up between one and 12 weeks in all but one study, which followed people up for 24 weeks. Six trials were funded by companies that produced paracetamol.

Key results

Compared with placebo tablets, paracetamol resulted in little benefit at 12 weeks.

Pain (lower scores mean less pain)

Improved by 3% (1% better to 5% better), or 3.2 points (1 better to 5.4 better) on a 0‐ to 100‐point scale.

• People who took paracetamol reported that their pain improved by 26 points.

• People who took placebo reported that their pain improved by 23 points.

Physical function (lower scores mean better function)

Improved by 3% (1% better to 5% better), or 2.9 points (1.0 better to 4.9 better) on a 0‐ to 100‐point scale.

• People who took paracetamol reported that their function improved by 15 points.

• People who had placebo reported that their function improved by 12 points.

Side effects (up to 12 to 24 weeks)

No more people had side effects with paracetamol (3% less to 3% more), or 0 more people out of 100.

• 33 out of 100 people reported a side effect with paracetamol.

• 33 out of 100 people reported a side effect with placebo.

Serious side effects (up to 12 to 24 weeks)

1% more people had serious side effects with paracetamol (0% less to 1% more), or one more person out of 100.

• Two out of 100 people reported a serious side effect with paracetamol.

• One out of 100 people reported a serious side effect with placebo.

Withdrawals due to adverse events (up to 12 to 24 weeks)

1% more people withdrew from treatment with paracetamol (1% less to 3% more), or one more person out of 100.

• Eight out of 100 people withdrew from paracetamol treatment.

• Seven out of 100 people withdrew from placebo treatment.

Abnormal liver function tests (up to 12 to 24 weeks):

5% more people had abnormal liver function tests (meaning there was some inflammation or damage to the liver) with paracetamol (1% more to 10% more), or five more people out of 100.

• Seven out of 100 people had an abnormal liver function test with paracetamol.

• Two out of 100 people had an abnormal liver function test with placebo.

Quality of the evidence

High‐quality evidence indicated that paracetamol provided only minimal improvements in pain and function for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis, with no increased risk of adverse events overall. None of the studies measured quality of life. Due to the small number of events, we were less certain if paracetamol use increased the risk of serious side effects, increased withdrawals due to side effects, and changed the rate of abnormal liver function tests. However, although there may be more abnormal liver function tests with paracetamol, the clinical implications are unknown.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Paracetamol versus placebo for hip or knee osteoarthritis.

| Paracetamol versus placebo for hip or knee osteoarthritis | ||||||

|

Population: people with hip or knee osteoarthritis Settings: various rehabilitation, orthopaedic, or rheumatology clinics Intervention: paracetamol Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Paracetamol | |||||

|

Mean change in pain (0–100 scale) Short term (3–12 weeks), where 0 = no pain |

The mean change in pain score in the placebo group was –23a | The mean change in pain score in the paracetamol group was 3.2 points lower (1.0 lower to 5.4 lower) |

MD –3.23 (–5.43 to –1.02) |

2355 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Clinically unimportant improvement; absolute change 3% better (5% better to 1% better); relative change 5% better (2% better to 8% better)b |

|

Physical function (WOMAC function 0–100) 3–12 weeks, 0 = better function |

The mean change in physical function score in the placebo group was –12a | The mean physical function score in the paracetamol group was 2.9 points lower (4.9 lower to 1.0 lower) |

MD –2.92 (–4.89 to –0.95) |

2354 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Clinically unimportant improvement; absolute change 3% better (5% better to 1% better); relative change 5% better (2% better to 9% better)b. |

|

Quality of life Not measured |

See comment | See comment | — | — | See comment | Not measured |

|

Withdrawals due to adverse events 24 weeks |

65 per 1000 |

77 per 1000 (59 to 100) |

RR 1.19 (0.91 to 1.55) | 3023 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The difference was not statistically or clinically significant; absolute change 1% more withdrew with paracetamol (1% less to 3% more); relative change 19% more (9% less to 55% more). |

|

Total adverse events: number experiencing 24 weeks |

325 per 1000 | 328 per 1000 (299 to 360) |

RR 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) |

3252 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | The difference was not statistically or clinically significant; absolute change: no more events with paracetamol (3% less to 3% more); relative change 1% more (8% less to 11% more). |

|

Liver toxicity: number experiencing abnormal liver function tests 24 weeks |

18 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (36 to 136) |

RR 3.79 (1.94to 7.39) |

1237 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | The clinical impact of the higher risk of abnormal liver function tests was unclear; absolute change 5% more abnormal tests with paracetamol (1% more to 10% more); relative change 279% more (94% more to 639% more). |

|

Serious adverse events: number experiencing 24 weeks |

11 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (8 to 29) |

RR 1.36 (0.73 to 2.53) |

3209 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | Absolute change: no more events with paracetamol (up to 1% more); relative change 36% more (27% less to 153% more). |

| *The basis for the assumed risk was the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference;RR: risk ratio; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aBased on score in placebo group at 3 months' follow‐up as reported in Miceli‐Richard 2004.

bRelative changes calculated as absolute change (mean difference) divided by mean at baseline in the placebo group from Miceli‐Richard 2004 (mean values were: 69.0 (standard deviation 17) on 0‐ to 100‐point visual analogue pain scale; and 54.0 (standard deviation 15) on 0‐ to 100‐point WOMAC function subscale).

cDowngraded by one level due to imprecision (small number of events, or the 95% confidence intervals do not exclude a clinically important change).

Background

Osteoarthritis of the hip or knee is the 11th highest contributor to global disability, when disability is measured by years lived with disability (Vos 2012), and its global prevalence is estimated at 4% (Cross 2014; Hoy 2014). In this context, it is important to manage osteoarthritis in an effective and efficient way (Barten 2015), and the control of pain symptoms is an important component of treatment (Prior 2014). The use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) is consistently recommended as the first‐line analgesic for this condition (Hochberg 2012; Zhang 2005). However, there has been controversy about using paracetamol in international clinical guidelines, mainly because previous studies have reported small effects for the medication compared with placebo (Towheed 2006; Zhang 2004; Zhang 2010). The perceived safety profile of paracetamol over other analgesics such as non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), has led to the increase of its use, resulting in paracetamol being among the most common non‐prescription medications used for osteoarthritis. However, there is evidence linking paracetamol with increased risk of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and kidney diseases, and mortality (Roberts 2016). A Cochrane Review of placebo‐controlled trials investigating the benefits of paracetamol for hip or knee osteoarthritis could provide credible information for clinical decision‐making based on the highest standard of evidence. This review is an update of a meta‐analysis on paracetamol for spinal pain or osteoarthritis (Machado 2015).

Description of the condition

Osteoarthritis is a complex and progressive joint disease characterised by focal cartilage loss, accompanied by subchondral bone changes and involvement of all joint tissues as deterioration of tendons and ligaments, and various degrees of inflammation of the synovium resulting from biomechanical and systemic effects (Hochberg 2012; Zhang 2010). This prevalent disease is associated with significant pain, stiffness, functional impairment, and reduced quality of life (Buckwalter 2006; Woolf 2003), resulting in a large societal and economic burden (Barten 2015).

Description of the intervention

Paracetamol is an antipyretic and analgesic medication that is not thought to have significant anti‐inflammatory properties. Although its mechanism of inducing analgesia is not yet completely understood, the drug is thought to work in part by decreasing production of prostaglandins through inhibitory effects involving cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) (Crofford 2001; Graham 2002; Graham 2013). Clinical practice guidelines for osteoarthritis management recommend paracetamol as the first choice when pain medication for osteoarthritis is needed, because of its safer profile compared with NSAIDs, particularly in people who are at risk of gastrointestinal ulcer (Zhang 2005; Zhang 2007). If paracetamol does not provide sufficient pain relief, then NSAIDs or other physical treatments may be considered (Bartels 2016; Derry 2016; Jüni 2015; Puljak 2017; Regnaux 2015; Smink 2011).

How the intervention might work

The details of the mechanism of action of paracetamol are now becoming clearer after its use for more than a century (Graham 2013). It is agreed that paracetamol inhibits the production of prostaglandins, which are mediators of fever, pain, and inflammation, by blocking the cyclo‐oxygenase pathways (Graham 2013). Paracetamol may have more central than peripheral analgesic effects and has similar but weaker anti‐inflammatory actions than NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen (Graham 2003; Graham 2013). Indeed, its pharmacological profile is of a weak selective COX‐2 inhibitor (Hinz 2008). One feature of paracetamol is its effectiveness in low levels of inflammation such as seen with tooth extraction. However, in contrast to selective COX‐2 inhibitors including celecoxib, paracetamol does not decrease intense inflammatory states such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout. COX‐1 and COX‐2 are bifunctional enzymes with cyclo‐oxygenase and peroxidase functions. Paracetamol is an inhibitor of the peroxidase function of COX‐1 and COX‐2 enzymes. From this process, it is effective in reducing prostaglandin synthesis when there are low levels of arachidonic acid, the precursor of prostaglandins. The analgesic effect of paracetamol is dependent upon several neurotransmitter systems in the central nervous system, including serotonin, opiate, and endogenous cannabinoid systems. In experimental studies, inhibitors of these systems block the analgesic effects of paracetamol (Graham 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

Pain is the most common symptom of osteoarthritis, and as pain levels rise, people experience a reduced range of motion and impaired physical function. The pain and functional limitations substantially reduce the quality of life of people with osteoarthritis. Paracetamol is a widely used analgesic for hip or knee osteoarthritis but the evidence on its benefits and harms remains controversial (Towheed 2006; Zhang 2004; Zhang 2010). The current review was conducted according to the guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Editorial Board (Ghogomu 2014), and is an update of the Machado 2015 review published in BMJ on 31 March 2015. This Cochrane Review has focused on data for hip and knee osteoarthritis and has included subgroup analysis on the dosage of paracetamol (i.e. 3.0 g/day or less or 3.9 g/day or more). Our updated search focusing on osteoarthritis trials identified 726 additional records; however, none of these records were eligible to be included in the review according to our inclusion criteria.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of paracetamol (acetaminophen) compared with placebo in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only published (full reports in a peer‐reviewed journal) randomised controlled trials comparing the benefits and harms of paracetamol with placebo for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Trials with quasi‐random allocation procedures were not included to avoid biased estimates of treatment effects. There were no restrictions for language or publication date.

Types of participants

We included only people with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee (intensity and duration of symptoms were not restricted). Both clinical and imaging‐based diagnoses of osteoarthritis were included in the review. People of any level of healthcare could be included: primary, secondary, or tertiary. We excluded trials evaluating analgesia in the immediate postoperative period, although studies in which participants had previous hip, or knee surgery were eligible, studies with mixed populations of participants with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis were also excluded, unless separate data were provided for osteoarthritis.

Types of interventions

Randomised controlled trials comparing the benefits of any dose regimen or administration mode of paracetamol versus placebo for hip or knee osteoarthritis. We have not included any study assessing the benefit and harm of the combination of paracetamol with any other type of medication.

Types of outcome measures

Major outcomes

The major outcomes were pain intensity, physical function, and quality of life ‐ as currently recommended for osteoarthritis trials (Altman 1996; Pham 2004), adverse events, serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, and liver toxicity. If data for more than one pain scale were provided in a trial, we referred to a previously described hierarchy of pain‐related outcomes (Juhl 2012; Jüni 2006; Reichenbach 2007), and extracted data on the pain scale that was highest on this list:

-

Pain intensity

pain overall;

pain on walking;

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscale;

pain on activities other than walking;

WOMAC global scale;

Lequesne Osteoarthritis Index global score;

other algofunctional scale;

patient’s global assessment;

physician's global assessment;

other outcome;

no continuous outcome reported.

If a trial provided data on more than one physical function impairment scale, we extracted data according to the following hierarchy:

-

Physical function

global disability score;

walking disability;

WOMAC disability subscore;

composite disability scores other than WOMAC;

disability other than walking;

Lequesne Osteoarthritis Index global score;

other algofunctional scale.

Quality of life.

Withdrawals due to adverse events.

Total adverse events.

Liver toxicity (positive alterations in liver function tests).

Serious adverse events.

Minor outcomes

Walking disability.

Rescue medication (rate of participants using rescue medication).

Patient adherence (rate of participants who adhered to at least 85% of prescribed number of tablets per day).

Long‐term toxicity (rate of participants reporting long‐term toxicity).

Radiographic joint structure changes (e.g. joint space width) were not included in this review, as it is unlikely paracetamol will have an effect on this outcome, thus we substituted liver toxicity as a major outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We updated the search (3 October 2017) on the following electronic databases, without restrictions on language:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL): via OvidSP, 1991 to October 2017;

MEDLINE: via OvidSP, 1946 to September Week 3 2017;

Embase: via OvidSP, 1974 to September 2017;

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED): via OvidSP, 1985 to September 2017;

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): via EBSCO, 1982 to September 2017;

Web of Science: via Thomson Reuters, 1900 to September 2017;

Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS): via BIREME, 1986 to September 2017;

International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA): via OvidSP, 1970 to September 2017.

We used a combination of relevant keywords to construct the search strategy including paracetamol, acetaminophen, osteoarthritis, osteoarthrosis, placebo, randomised, and controlled trial. Two review authors (GCM and MBP) conducted the first screening of potentially relevant records based on titles and abstract, and three review authors (GCM, MBP, and AAO for the update) independently performed the final selection of included trials based on full‐text evaluation. We performed citation tracking on included studies and relevant systematic reviews, and searched relevant websites and clinical trials registries for unpublished studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus between the three review authors. The search strategy for each database is presented in the following appendices: Appendix 1 (CENTRAL), Appendix 2 (MEDLINE), Appendix 3 (Embase), Appendix 4 (AMED), Appendix 5 (CINAHL), Appendix 6 (Web of Sciences), Appendix 7 (LILACS), and Appendix 8 (IPA).

Searching other resources

The review authors had previously contacted the pharmaceutical manufacturers for details of unpublished and ongoing trials. We searched and identified the relevant trials or reviews in reference lists. We also searched clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) on 20 October 2017, and asked personal contacts about ongoing and unpublished studies. There were no language or publication restrictions. See search strategy for unpublished and ongoing trials in Appendix 9.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (GCM, MBP, and AAO) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the updated searches using a standardised data extraction form to eliminate those that clearly did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. We obtained full reports for the remaining studies to determine inclusion in the review. A fourth review author (MLF) resolved any disagreements. If multiple reports described the same trial, we considered all. In case of multiple reports of the same study, these were collated, so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (GCM, MBP, and AAO) independently extracted trial information using a standardised data collection form. Review authors were not blinded to the authors' names and institutions, journal of publication, or study results at any stage of the review. We resolved disagreements through discussion. One review author (AAO) entered data suitable for meta‐analysis into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2012), and another review author (GCM) double checked entries. We extracted the following data:

bibliometric data: authors, affiliations, language, and year of publication;

characteristics of included trials: trial design, sample size, details of participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria, characteristics of the experimental intervention, type of control used, dosage, frequency, duration of treatment interventions, duration of follow‐up, and primary and secondary outcomes;

characteristics of included participants: age, sex, type of diagnosis for hip and knee osteoarthritis, types of joints affected (knee, hip, or both), and duration of symptoms;

statistical data: means, standard deviations (SD), and sample sizes for major outcomes. We extracted mean estimates in the following hierarchical order: change scores, and final values.

For our minor outcomes, we extracted the number of cases and the total sample size. The safety outcomes extracted from included trials were the number of participants reporting any adverse effect, number of participants reporting any serious adverse effect (as defined by each study), number of participants who withdrew from the study because of adverse effects, and number of participants with abnormal results on liver function tests (hepatic enzyme activity 1.5 times the upper limit of the reference range or greater).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GCM and MBP) independently assessed 'Risk of bias' for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed each included study within the following 'Risk of bias' domains: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding, how incomplete outcome data (dropouts) were addressed, evidence of selective outcome reporting, and whether trials were funded by companies that produced paracetamol. We resolved disagreements by consensus. We used Review Manager 5 to generate figures and summaries (Review Manager 2012).

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous data based on the number of events in the control and intervention groups of each study. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% CI between paracetamol and placebo groups. Pain and physical function (WOMAC function) scores were converted to a common 0 (no pain or disability) to 100 (worst possible pain or disability) scale before meta‐analysis. We considered a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 9 points on a 100‐point scale for pain and physical function outcomes based upon the practice in the osteoarthritis field (Wandel 2010).

In the Comments column of the 'Summary of findings' table, we reported the absolute percent difference, the relative percent change from baseline, and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (NNTB and NNTH were provided only when the outcome showed a clinically important difference between treatment groups).

For dichotomous outcomes, such as adverse events, we calculated the NNTB or NNTH from the control group event rate and the relative risk using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2008). We calculated the NNTB for continuous measures using the Wells calculator (available at the CMSG Editorial office, musculoskeletal.cochrane.org/). We used the MCID to interpret results, and for input into the Wells calculator. We assumed an MCID of 9 points in a 10‐point scale for pain (Wandel 2010); and 10 points on a 100‐point scale for function or disability.

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the absolute risk difference using the Risk Difference statistic in Review Manager 5 and expressed the result as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, we calculated the absolute benefit as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group (MD), in the original units, and expressed it as a percentage.

We calculated the relative percent change for dichotomous data as the RR – 1 and expressed it as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, we calculated the relative difference as the absolute benefit divided by the baseline mean of the control group, expressed as a percentage.

Unit of analysis issues

Seven included studies were traditional randomised parallel‐group trials and three were crossover trials (Pincus 2004a; Pincus 2004b; Amadio 1983). The unit of analysis was between‐person for all trials. We stratified all outcomes into four time points of assessment for the primary analyses: immediate term (two weeks or less), short term (more than two weeks but three months or less), intermediate term (more than three months but 12 months or less), and long term (more than 12 months). When studies reported multiple time points within each category, we used the time point closest to one week for immediate term, eight weeks for short term, six months for intermediate term, and 12 months for long term (although no studies reported long‐term outcomes and only one reported intermediate‐term outcomes). For studies reporting on multiple intervention groups (e.g. groups of different dosages) and included in the same pooled analysis, we halved the sample size of the placebo group to avoid unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the studies to obtain data that were missing or insufficient in their report that we needed to assess eligibility of the studies or as input for meta‐analysis, or both. If statistics were missing, such as SD, we calculated them from other available statistics (e.g. 95% CIs), according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity using visual inspection of effect size distribution and overlap of the CIs in forest plots, as well as using results of the Chi² test and the I² statistic as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered studies to be statistically heterogeneous if the I² statistic was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to assess publication bias but we had fewer than 10 trials included in any particular pooled analysis.

Data synthesis

We entered all quantitative results into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2012). We pooled data (statistical pooling with meta‐analysis) for the comparison paracetamol versus placebo for each outcome for which data were reported in trials. We used a random‐effects model for all analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

We created Table 1 for the following outcomes: pain, physical function, quality of life, any adverse events, serious adverse events, withdrawals due to adverse events, and liver toxicity (positive for abnormal results on liver function tests). We included data from the short‐term follow‐up times (three to 12 weeks) for pain and function and data from the last follow‐up time point (between 12 and 24 weeks) for adverse events and withdrawals.

We used the GRADE system to assess the quality of the evidence for each pooled analysis (Guyatt 2008), defined as the extent of confidence into the estimates of treatment benefits and harms, with outcomes of interest being ranked according to their relevance for clinical decision making as of limited importance, important, or critical (Guyatt 2011). The overall quality of the evidence for each outcome was based on 'Risk of bias,' publication bias, inconsistency of results, indirectness, and imprecision (Guyatt 2008; Higgins 2011). For 'Risk of bias,' we downgraded the quality of the evidence if more than 25% of participants were from studies with an overall high 'Risk of bias.' We aimed to assess publication bias by visual inspection of funnel plots (scatterplot of the effect of estimates from individual studies against its standard error) and also by the results of Egger's test (small‐study effects) (Egger 1997). If the Egger's test result was significant (two tailed P < 0.1), we downgraded the quality of evidence (GRADE) by one level for publication bias for all meta‐analyses (Guyatt 2011). Results were downgraded for inconsistency if there was significant heterogeneity present by visual inspection or if the I² value was greater than 50%. We downgraded the evidence for imprecision if the limits of the 95% CI crossed the MCID for continuous outcomes, or there were fewer than 200 events for dichotomous outcomes. The GRADE Working Group recommends four levels of evidence:

high‐quality evidence: further research is very unlikely to change confidence in estimate of effect;

moderate‐quality evidence: further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

low‐quality evidence: further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate;

very low‐quality evidence: very little confidence in the effect estimate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to assess if pain and function differed between people with hip or knee osteoarthritis, and with the dose of paracetamol (3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted no sensitivity analyses for this review.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

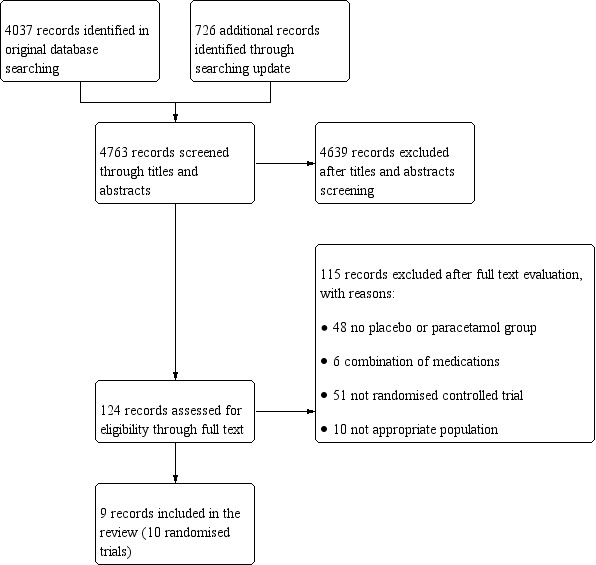

The updated search resulted in 1033 additional records with duplicates: 127 additional references from CENTRAL, 242 from MEDLINE, 243 from Embase, 15 from AMED, 250 from CINAHL, 113 from Web of Sciences, 17 from LILACS, and 26 from IPA. After excluding 307 duplicates, we screened 726 titles and abstracts, and eight additional potentially relevant papers for full‐text evaluation. There were no new studies for inclusion in this update, therefore, we analysed the original nine records, or 10 randomised controlled trials (Altman 2007; Amadio 1983; Case 2003; Golden 2004; Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Miceli‐Richard 2004; Pincus 2004a; Pincus 2004b; Prior 2014; Zoppi 1995). We presented the flow chart of the original and updated search in Figure 1.

1.

Prisma flow diagram of trials investigating efficacy of paracetamol versus placebo for osteoarthritis.

Included studies

The review includes nine records reporting 10 randomised controlled trials and yielded a pooled sample size of 3541 participants. One paper reported on the results of two separate randomised trials (Pincus 2004a; Pincus 2004b). Details of included studies are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. Years of publication ranged from 1983 to 2014 and all studies were double‐blind randomised placebo‐controlled trials. The follow‐up time ranged from one to 24 weeks. Paracetamol was administered orally (as tablets or capsules). The total oral dose and dose regimens for paracetamol varied across trials. Doses ranged from 1.95 g/day to 4 g/day, but no trials used paracetamol doses between 3.0 to 3.9 g/day. One trial used a three‐arm design (Altman 2007), and all three treatment groups were included in the meta‐analyses following the recommendation in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The washout period before treatment started varied across trials, ranging from one day to six months. The washout periods were 12 weeks for corticosteroids, six weeks for intra‐articular steroids, and three days to two weeks for NSAIDs. Participants stopped taking simple analgesics from one to 10 days. One trial reported that the washout for glucosamine drugs was six months, and two trials used "five half lives" to define this period. Nine trials used the diagnosis of osteoarthritis based on image evidence and clinical assessment, whereas one trial based the diagnosis solely on image evidence.

Excluded studies

For this update, after retrieving the full text for final assessment, the review authors excluded eight studies: three were not randomised controlled trials (Papou 2015; van Tunen 2016; Zheng 2015), one study did not investigate paracetamol and lacked a placebo control group (Skou 2015), one study did not include people with hip or knee osteoarthritis (Park 2015), two trials did not investigate paracetamol (Ha 2016; Lao 2015), and one trial lacked a placebo control group (Verkleij 2015). See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Ongoing studies

An additional search for protocols or unpublished trials identified 74 records. Five ongoing studies that fit the inclusion criteria were found on ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP. One registered clinical trial was withdrawn (NCT01420666), and two had no results posted online (ACTRN12613000840785; NCT02845271). Two records provided results posted online, but not in a peer‐reviewed journal (NCT01105936; NCT02311881).

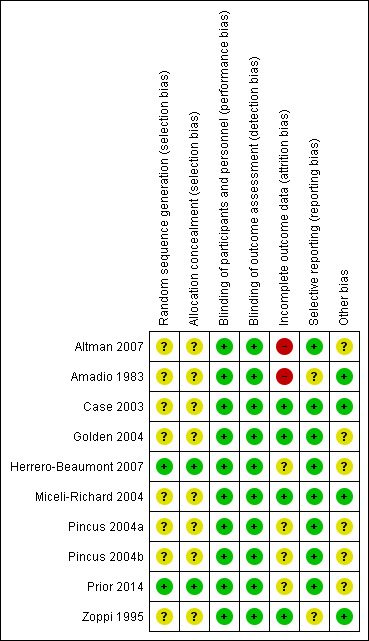

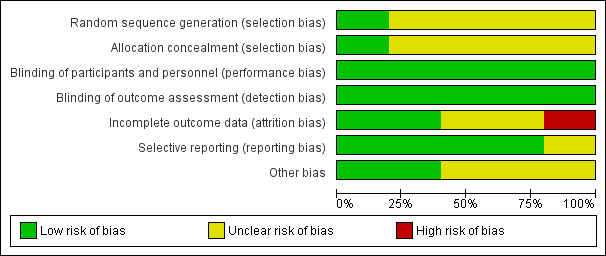

Risk of bias in included studies

The results from the 'Risk of bias' assessment are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

In general, included trials did not describe their randomisation and allocation processes adequately and were at unclear risk of selection bias. Only two trials adopted appropriate methods of sequence generation and allocation concealment and were at low risk of selection bias (Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Prior 2014).

Blinding

All included trials successfully reported blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors and were at low risk of performance and detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies had follow‐up rates of 90% or higher were at low risk of attrition bias (Case 2003; Golden 2004; Miceli‐Richard 2004; Zoppi 1995). Two trials were at high risk of attrition bias due to high dropout rates (Altman 2007; Amadio 1983), and the remaining four trials were at unclear risk, since there were no significant differences in the reasons for dropout between the groups despite the large dropout rate.

Selective reporting

One trial did not include measures of physical function (Zoppi 1995), and one trial did not report pain outcome measures (Amadio 1983), and were at unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Six trials were funded by companies that produced paracetamol and were at unclear risk of bias for the other sources of bias domain (Altman 2007; Golden 2004; Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Pincus 2004a; Pincus 2004b; Prior 2014).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Results are presented separately according to outcome measures and follow‐up time points. No studies measured results after six months, thus we reported pain and physical function outcomes at immediate term (two weeks or less) and short term (more than two weeks to three months or less) only.

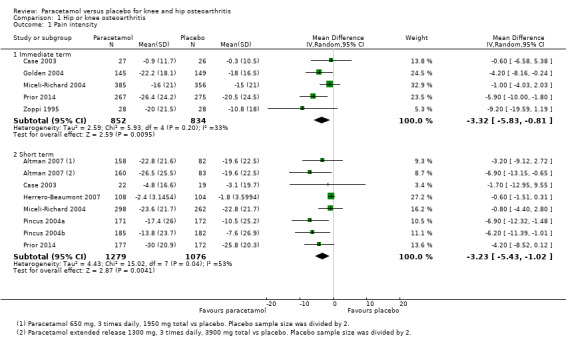

Major outcomes

Pain intensity

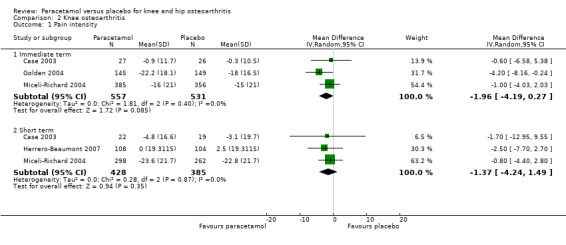

There was high‐quality evidence that paracetamol provided a small, likely clinically unimportant improvement in pain in the immediate term (MD –3.32, 95% CI –5.83 to –0.81; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4) and the short term (MD –3.23, 95% CI –5.43 to –1.02; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4; Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, outcome: 1.1 Pain. Pain scores are expressed on scale of 0 to 100. Immediate term = follow‐up two weeks or less; short term = follow‐up more than two weeks but three months or less.

Physical function

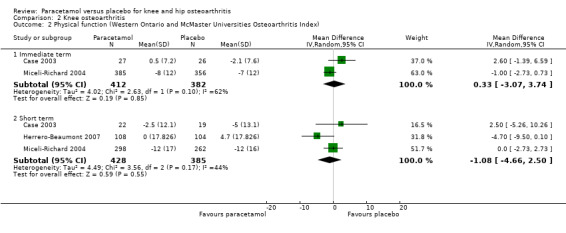

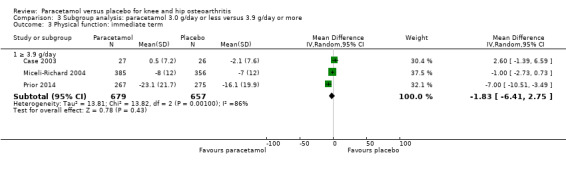

Moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded for inconsistency) indicating there was probably no difference between groups in physical function in the immediate term (MD –1.83, 95% CI –6.41 to 2.75; Analysis 1.2; Figure 5), and high‐quality evidence indicated a small clinically unimportant improvement with paracetamol in the short term (MD –2.92, 95% CI –4.89 to –0.95; Analysis 1.2; Figure 5; Table 1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 2 Physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, outcome: 1.2 Physical function (WOMAC). Physical function scores expressed on scale of 0 to 100. Immediate term = follow‐up two weeks or less; short term = follow‐up two weeks or greater but three months or less.

Quality of life

None of the studies measured quality of life.

Withdrawals due to adverse events

There was less certainty due to small event rates, indicating imprecision (moderate‐quality evidence), around the risk of withdrawals due to adverse events with paracetamol (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.55).

Total adverse events

There was high‐quality evidence indicating that the risk of any adverse event was similar between paracetamol and placebo treatment groups (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.11; Analysis 1.3; Figure 6; Table 1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 3 Adverse events (AE).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, outcome: 1.4 Adverse events (AE). Any = number of participants reporting any AE; serious = number of participants reporting any serious AE (as defined by each study); withdrawals = number of participants withdrawn from study because of AEs; liver = number of participants with abnormal results on liver function tests.

Liver toxicity

Abnormal liver function tests were more likely to occur with paracetamol (RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.94 to 7.39), but the evidence was downgraded due to wide CIs (imprecision), indicating uncertainty around these effect estimates.

Serious adverse events

There was less certainty due to small event rates, indicating imprecision (moderate‐quality evidence), around the risk of serious adverse events with paracetamol (RR 1.36, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.53).

Minor outcomes

Low‐quality evidence for minor outcomes was available from single studies only with potential risk of selection or attrition bias (downgraded for risk of bias and imprecision).

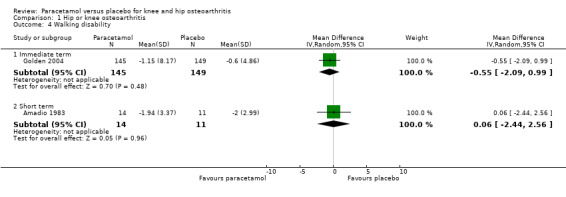

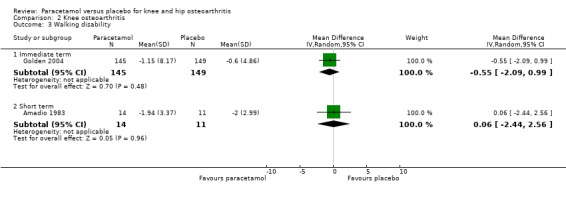

Walking disability

It was uncertain if walking disability (measured using the 50‐foot walking test) differed between paracetamol and placebo groups in the immediate term (RR –0.55, 95% CI –2.09 to 0.99) and short term (RR 0.06, 95% CI –2.44 to 2.56; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 4 Walking disability.

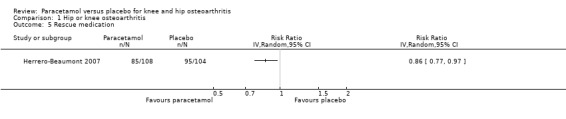

Rescue medication

it was uncertain if the use of rescue analgesic medication differed between paracetamol and placebo groups (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.97; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 5 Rescue medication.

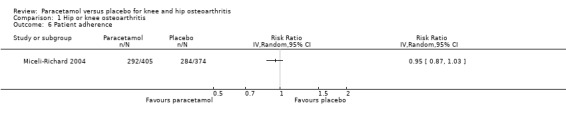

Patient adherence

it is uncertain if adherence to treatment differed between paracetamol and placebo groups adherence to treatment (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.03; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hip or knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 6 Patient adherence.

Long‐term toxicity

None of the studies measured long‐term toxicity.

Subgroup analyses

We planned subgroup analyses to assess for potential differences in outcomes in participants with knee osteoarthritis and those with hip osteoarthritis, but data for participants with hip and knee osteoarthritis were not presented separately in the included studies. A subset of trials included participants with knee osteoarthritis only (Amadio 1983; Case 2003; Golden 2004; Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Miceli‐Richard 2004), and four trials reported pain and function (Case 2003; Golden 2004; Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Miceli‐Richard 2004). Moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded for imprecision) indicated that paracetamol provided no important improvement in pain at immediate follow‐up (MD –1.96, 95% CI –4.19 to 0.27) or short‐term follow‐up (MD –1.37, 95% CI –4.24 to 1.49) (Analysis 2.1). There were similar results for physical function at immediate follow‐up (MD 0.33, 95% CI –3.07 to 3.74) and short‐term follow‐up (MD –1.08, 95% CI –4.66 to 2.50). See: Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 2 Physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Knee osteoarthritis, Outcome 3 Walking disability.

Up to nine trials presented data for the subgroup analysis comparing lower and higher dose of paracetamol (3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more) (Altman 2007; Case 2003; Golden 2004; Herrero‐Beaumont 2007; Miceli‐Richard 2004; Pincus 2004a; Pincus 2004b; Prior 2014; Zoppi 1995). There were no important differences in outcomes for low‐dose versus high‐dose paracetamol with respect to pain in the immediate term (Analysis 3.1) or short term (Analysis 3.2), or physical function in the short term (Analysis 3.4). We could not perform a subgroup analysis in the immediate term for physical function as no studies using lower‐dose paracetamol reported this outcome at this time point.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: paracetamol 3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more, Outcome 1 Pain intensity: immediate term.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: paracetamol 3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more, Outcome 2 Pain intensity: short term.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: paracetamol 3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more, Outcome 4 Physical function: short term.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this update of the systematic review and meta‐analysis by Machado 2015, we included nine eligible records reporting 10 randomised placebo‐controlled trials (3541 participants) on the effects of paracetamol and placebo for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Thresholds for clinical importance were chosen a priori and included 9 points for pain and physical function (on a 100‐point scale). In general, there was moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence that treatment effects of paracetamol compared with placebo on both pain and physical function outcomes were, at best, too small to be of clinical relevance for this population. Although the risk of total adverse events likely did not differ between the paracetamol and placebo groups (high‐quality evidence), the use of paracetamol may have increased the risk of abnormal liver test results (moderate‐quality evidence, downgraded for imprecision). However, we acknowledge that the clinical importance of this finding was uncertain. Due to the small number of events, we were less certain if paracetamol use increased the risk of serious adverse events or withdrawals due to adverse events. Our subgroup analyses indicated that the effects on pain and function did not differ according to the dose of paracetamol (3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more). We did not include a responder analysis in this review, as thresholds used to define responders in this field are still not well defined. It is possible, however, that the results of a responder analysis would yield different conclusions.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Paracetamol is the most commonly used non‐prescription medication for musculoskeletal pain, including osteoarthritis (Brand 2014), but this systematic review has shown that there is moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence that the effects of paracetamol compared with placebo are too small to be of clinically importance for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Given only one trial included a follow‐up longer than 12 weeks (Herrero‐Beaumont 2007), the results of this review are mostly restricted to immediate‐ and short‐term follow‐ups.

Previous research has highlighted that the focus on pharmacological interventions for knee and hip osteoarthritis is in disconnect with the best evidence‐based recommendations for care of this condition (Brand 2008; Brand 2014). For instance, there is a very important component of lifestyle‐based management, such as obesity control and physical activity uptake that is not addressed with pharmacological approaches (Basedow 2015; Brand 2008). In fact, evidence has established that physical programmes (e.g. weight loss, exercise including lower limb strengthening exercises) are associated with large effect sizes (greater than 20) on pain reduction in this population (Uthman 2013). Our results showed that pharmacological management of hip or knee osteoarthritis through simple analgesics only offers small and clinically unimportant effects on pain and physical function.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of evidence for the outcomes measured up to 12 weeks considered critical for clinical decision making (pain, function, and overall adverse events) was high according to the GRADE system. According to the GRADE Working Group, a grading of high quality of evidence indicates that further research is unlikely to change the effect estimates substantially. For serious adverse events (short term), withdrawals due to adverse events and liver toxicity (indicated by abnormal liver function tests), evidence was downgraded from high to moderate due to imprecision (the total number of events was small). According to the GRADE Working Group grades of evidence, a grading of moderate quality of evidence indicates that further research may have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

None of the trials measured quality of life or long‐term toxicity outcomes.

Potential biases in the review process

We based our review on an extensive electronic literature search, citation tracking, and search for unpublished trials, so it seems unlikely that we missed relevant trials, provided that they were published as full‐text articles or accessible in conference proceedings or trial registries (Egger 2003). Two review authors independently performed selection of trials, data extraction, and 'Risk of bias' assessment to reduce bias and transcription errors (Gøtzsche 2007). Therefore, we are confident that potential biases during the review process were minimised. However, the review presented some limitations. The number of studies in each meta‐analysis was relatively small and that prevented us from conducting a small‐study effect analysis using funnel plots. Previous exposure of participants to paracetamol was also frequently reported by included trials, suggesting that a proportion of 'non‐responders' to the medication were possibly included in the analyses. We acknowledge this could have influenced the final results.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The previous non‐Cochrane review on paracetamol for hip or knee osteoarthritis was conducted in 2004 (Zhang 2004), after which, six additional randomised placebo‐controlled trials were published. The authors of this previous review included trials of osteoarthritis affecting multiple joints and not just the hip or knee. Moreover, they included analyses comparing NSAIDs versus paracetamol and NSAIDs versus placebo. Zhang 2004 concluded that paracetamol was an effective analgesic medication for pain relief due to osteoarthritis (standardised mean difference 0.21, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.41). However, in this update of Machado 2015, we included subgroup analyses to verify possible differences between the two body regions (hip and knee) and dose of paracetamol (3 g/day or 4 g/day) on pain and physical function. Our review has provided moderate‐ to high‐quality evidence that the effects of paracetamol on pain and function were not different when comparing hip or knee osteoarthritis or different doses used, and were too small to be considered clinically relevant.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Despite guidelines for the treatment of non‐traumatic knee complaints recommending paracetamol as the first‐choice analgesic in treating pain due to osteoarthritis (Jordan 2003; Zhang 2007), this updated review confirms previous findings that paracetamol provides minimal, probably clinically unimportant benefits in the immediate and short term for people with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Moreover, paracetamol does not provide statistically significant or clinically important effects for people with knee osteoarthritis only.

Implications for research.

The use of drugs as an intervention has been previously associated with improvements on pain and physical function in people with osteoarthritis (Barthel 2010; Schein 2008). However, this Cochrane systematic review including only randomised placebo‐controlled trials investigating the benefits and harms of paracetamol compared with placebo for hip and knee osteoarthritis revealed that paracetamol alone does not offer clinically important benefits for this population. These results were consistent irrespective of the dose of paracetamol or pain location. Future research should focus on developing and implementing models of care that are focused on evidence‐based non‐pharmacological approaches for the care of knee and hip osteoarthritis.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 August 2019 | Amended | Typographical error corrected in the plain language summary |

Acknowledgements

This research received no funding from the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors. AOL is supported by CNPQ (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnologico), Brazil. DJH holds a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship. MLF holds a fellowship from Sydney Medical Foundation/Sydney Medical School.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

acetaminophen.mp. OR exp Acetaminophen/

Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic/tu

(paracetamol OR tylenol OR panadol).mp.

OR/1‐3

exp Osteoarthritis, Hip/ OR exp Osteoarthritis/ OR exp Osteoarthritis, Spine/ OR exp Osteoarthritis, Knee/

low back pain.mp. OR exp Low Back Pain/

neck pain.mp. OR exp Neck Pain/

("low back pain" OR "back pain" OR "neck pain" OR backache OR lumbago OR "neck ache" OR "spin* pain" OR "knee pain" OR "hip pain").mp.

OR/5‐8

4 and 9

limit 10 to yr="2015 ‐Current"

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

acetaminophen.mp. OR exp Acetaminophen/

paracetamol.mp

analgesic*.ab,ti. OR Analgesics, Non‐Narcotic/tu, th

(aceta OR actimin OR anacin OR apacet OR "aspirin free anacin" OR acamol OR acetalgin OR adol OR aldolOR OR alvedon OR apiretal OR atamel OR atasol OR benuron OR biogesic OR "biogesic kiddielets" OR buscapina OR banesin OR "ben u ron" OR calpol OR captin OR cemol OR coldex OR cotibin OR crocin OR dafalgan OR daleron OR "dawa ya magi" OR depon OR dexamol OR dolex OR dolgesic OR doliprane OR dolorol OR dolprone OR "duiyixian anjifen pian" OR dapa OR dolo OR datril OR duatrol OR dayquil OR efferalgan OR enelfa OR europain OR febrectal OR febricet OR febridol OR fensum OR feverall OR fibi OR "fibi plus" OR gelocatil OR gripin OR gesic OR genapap OR genebs OR hedex OR hedanol OR herron OR influbene OR kafa OR kitadol OR lekadol OR lupocet OR lemsip OR liquiprin OR pyrigesic OR mexalen OR milidon OR minoset OR momentum OR napa OR "neo kiddielets" OR neopap OR "oraphen pd" OR pyrigesic OR pacol OR pamol OR parol OR panado OR panadol OR panamax OR panda OR panodil OR pyrigesic OR paracet OR paracetamol OR paracitol OR paralen OR paramed OR paramol OR parol OR perdolan OR perfalgan OR pinex OR "pyongsu cetamol" OR pyrenol OR pyrigesic OR plicet OR panadrex OR paratabs OR paralgin OR phenaphen OR revanin OR rokamol OR rubophen OR redutemp OR sara OR scanol OR "sinpro n" OR "snaplets fr" OR suppap OR tachipirin OR tachipirina OR tafirol OR tapsin OR termalgin OR tempra OR thomapyrin OR tipol OR "togal classic duo" OR treuphadol OR triaminic OR tylenol OR tamen OR tapanol OR tipol OR uphamol OR vermidon OR vitamol OR valorin OR xumadol OR zolben).tw.

OR/1‐4

osteoarthritis.mp. OR exp Osteoarthritis/

exp Low Back Pain/

exp Back Pain/

exp Neck Pain/

("low back pain" OR "back pain" OR "neck pain" OR backache OR lumbago OR "neck ache" OR "spin* pain" OR "knee pain" OR "hip pain").mp.

OR/6‐10

randomized controlled trial.pt. OR exp Randomized Controlled Trial/

"randomized controlled trial".mp.

exp Random Allocation/

placebo.mp. OR exp Placebos/ OR exp Placebo Effect/

(random* adj3 trial).ab,ti.

"controlled clinical trial".mp. OR exp Controlled Clinical Trial/

random*.ab,ti.

OR/12‐18

5 AND 11 AND 19

(2015* 2016* or 2017*).dp. or (2015* or 2016* or 2017*).ed.

20 AND 21

limit 22 to humans

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy

acetaminophen.mp. OR paracetamol.mp. OR Paracetamol/

(aceta OR actimin OR anacin OR apacet OR "aspirin free anacin" OR acamol OR acetalgin OR adol OR aldolOR OR alvedon OR apiretal OR atamel OR atasol OR benuron OR biogesic OR "biogesic kiddielets" OR buscapina OR banesin OR "ben u ron" OR calpol OR captin OR cemol OR coldex OR cotibin OR crocin OR dafalgan OR daleron OR "dawa ya magi" OR depon OR dexamol OR dolex OR dolgesic OR doliprane OR dolorol OR dolprone OR "duiyixian anjifen pian" OR dapa OR dolo OR datril OR duatrol OR dayquil OR efferalgan OR enelfa OR europain OR febrectal OR febricet OR febridol OR fensum OR feverall OR fibi OR "fibi plus" OR gelocatil OR gripin OR gesic OR genapap OR genebs OR hedex OR hedanol OR herron OR influbene OR kafa OR kitadol OR lekadol OR lupocet OR lemsip OR liquiprin OR pyrigesic OR mexalen OR milidon OR minoset OR momentum OR napa OR "neo kiddielets" OR neopap OR "oraphen pd" OR pyrigesic OR pacol OR pamol OR parol OR panado OR panadol OR panamax OR panda OR panodil OR pyrigesic OR paracet OR paracetamol OR paracitol OR paralen OR paramed OR paramol OR parol OR perdolan OR perfalgan OR pinex OR "pyongsu cetamol" OR pyrenol OR pyrigesic OR plicet OR panadrex OR paratabs OR paralgin OR phenaphen OR revanin OR rokamol OR rubophen OR redutemp OR sara OR scanol OR "sinpro n" OR "snaplets fr" OR suppap OR tachipirin OR tachipirina OR tafirol OR tapsin OR termalgin OR tempra OR thomapyrin OR tipol OR "togal classic duo" OR treuphadol OR triaminic OR tylenol OR tamen OR tapanol OR tipol OR uphamol OR vermidon OR vitamol OR valorin OR xumadol OR zolben).mp.

OR/1‐2

osteoarthritis.mp. OR Osteoarthritis/

low back pain.mp. OR Low Back Pain/

backache.mp. OR Backache/

neck pain.mp. OR Neck Pain/

("low back pain" OR "back pain" OR "neck pain" OR backache OR lumbago OR "neck ache" OR "spin* pain" OR "knee pain" OR "hip pain").mp.

OR/4‐8

randomized controlled trial.mp. OR Randomized Controlled Trial/

randomization.mp. OR Randomization/

placebo.mp. OR Placebo/

randomized.ti,ab

placebo.ti,ab

randomly.ti,ab

OR/10‐15

3 AND 9 AND 16

(2015* or 2016* or 2017*).dd. or (2015* or 2016* or 2017*).dp.

17 AND 18

limit 19 to human

Appendix 4. AMED search strategy

acetaminophen.mp. OR exp Acetaminophen/

analgesics.mp. OR exp Analgesics/

drug therapy.mp. OR exp Drug Therapy/

analgesic*.ab,ti.

(aceta OR actimin OR anacin OR apacet OR "aspirin free anacin" OR acamol OR acetalgin OR adol OR aldolor OR alvedon OR apiretal OR atamel OR atasol OR benuron OR biogesic OR "biogesic kiddielets" OR buscapina OR banesin OR "ben u ron" OR calpol OR captin OR cemol OR coldex OR cotibin OR crocin OR dafalgan OR daleron OR "dawa ya magi" OR depon OR dexamol OR dolex OR dolgesic OR doliprane OR dolorol OR dolprone OR "duiyixian anjifen pian" OR dapa OR dolo OR datril OR duatrol OR dayquil OR efferalgan OR enelfa OR europain OR febrectal OR febricet OR febridol OR fensum OR feverall OR fibi OR "fibi plus" OR gelocatil OR gripin OR gesic OR genapap OR genebs OR hedex OR hedanol OR herron OR influbene OR kafa OR kitadol OR lekadol OR lupocet OR lemsip OR liquiprin OR pyrigesic OR mexalen OR milidon OR minoset OR momentum OR napa OR "neo kiddielets" OR neopap OR "oraphen pd" OR pyrigesic OR pacol OR pamol OR parol OR panado OR panadol OR panamax OR panda OR panodil OR pyrigesic OR paracet OR paracetamol OR paracitol OR paralen OR paramed OR paramol OR parol OR perdolan OR perfalgan OR pinex OR "pyongsu cetamol" OR pyrenol OR pyrigesic OR plicet OR panadrex OR paratabs OR paralgin OR phenaphen OR revanin OR rokamol OR rubophen OR redutemp OR sara OR scanol OR "sinpro n" OR "snaplets fr" OR suppap OR tachipirin OR tachipirina OR tafirol OR tapsin OR termalgin OR tempra OR thomapyrin OR tipol OR "togal classic duo" OR treuphadol OR triaminic OR tylenol OR tamen OR tapanol OR tipol OR uphamol OR vermidon OR vitamol OR valorin OR xumadol OR zolben).tw.

OR/1‐5

osteoarthritis.mp. OR exp Osteoarthritis/

low back pain.mp. OR exp Low Back Pain/

back pain.mp. OR exp Backache/

neck pain.mp. OR exp Neck Pain/

("low back pain" OR "back pain" OR "neck pain" OR backache OR lumbago OR "neck ache" OR "spin* pain" OR "knee pain" OR "hip pain").mp.

OR/7‐11

randomized controlled trial.mp. OR exp Randomized Controlled Trials/

randomized controlled trial.pt.

random allocation.mp. OR exp Random Allocation/

placebo.mp. OR exp Placebos/

(random* adj3 trial).ab,ti.

random*.ab,ti.

OR/13‐18

6 AND 12 AND 19

limit 20 to yr="2015 ‐Current"

Appendix 5. CINAHL search strategy

(MH "Acetaminophen") OR "acetaminophen"

(MH "Analgesics+/TU")

"analgesic$"

"paracetamol"

"tylenol"

"panadol"

OR/1‐6

(MH "Osteoarthritis+") OR "osteoarthritis" OR (MH "Osteoarthritis, Spine+") OR (MH "Osteoarthritis, Knee") OR (MH "Osteoarthritis, Hip")

(MH "Low Back Pain") OR "low back pain" OR (MH "Back Pain+")

(MH "Neck Pain") OR "neck pain"

(MH "Knee Pain+") OR "knee pain"

"hip pain"

"backache"

OR/8‐13

7 AND 14

EM 201501‐

DT 2015‐

OR/16‐17

15 AND 18

Appendix 6. Web of Sciences search strategy

acetaminophen

Paracetamol OR tylenol OR panadol

OR/1‐2

osteoarthritis

back pain

neck pain

(spin* pain" OR "knee pain" OR "hip pain")

OR/4‐7

3 AND 8

randomized controlled trial

random allocation

placebo

controlled clinical trial

Random*

OR/10‐14

9 AND 15 (Timespan=2015‐2017)

Appendix 7. LILACS search strategy

((acetaminophen OR paracetamol OR tylenol OR panadol) AND (osteoarthritis OR back pain OR lumbago OR backache OR neck pain)) AND (instance:"regional") AND (db:("LILACS") AND year_cluster:("2015" OR "2016" OR "2017"))

Appendix 8. IPA search strategy

acetaminophen.mp.

(aceta or actimin or anacin or apacet or "aspirin free anacin" or acamol or acetalgin or adol or aldolOR or alvedon or apiretal or atamel or atasol or benuron or biogesic or "biogesic kiddielets" or buscapina or banesin or "ben u ron" or calpol or captin or cemol or coldex or cotibin or crocin or dafalgan or daleron or "dawa ya magi" or depon or dexamol or dolex or dolgesic or doliprane or dolorol or dolprone or "duiyixian anjifen pian" or dapa or dolo or datril or duatrol or dayquil or efferalgan or enelfa or europain or febrectal or febricet or febridol or fensum or feverall or fibi or "fibi plus" or gelocatil or gripin or gesic or genapap or genebs or hedex or hedanol or herron or influbene or kafa or kitadol or lekadol or lupocet or lemsip or liquiprin or pyrigesic or mexalen or milidon or minoset or momentum or napa or "neo kiddielets" or neopap or "oraphen pd" or pyrigesic or pacol or pamol or parol or panado or panadol or panamax or panda or panodil or pyrigesic or paracet or paracetamol or paracitol or paralen or paramed or paramol or parol or perdolan or perfalgan or pinex or "pyongsu cetamol" or pyrenol or pyrigesic or plicet or panadrex or paratabs or paralgin or phenaphen or revanin or rokamol or rubophen or redutemp or sara or scanol or "sinpro n" or "snaplets fr" or suppap or tachipirin or tachipirina or tafirol or tapsin or termalgin or tempra or thomapyrin or tipol or "togal classic duo" or treuphadol or triaminic or tylenol or tamen or tapanol or tipol or uphamol or vermidon or vitamol or valorin or xumadol or zolben).tw.

OR/1‐2

osteoarthritis.mp.

low back pain.mp.

back pain.mp.

neck pain.mp.

("low back pain" or "back pain" or "neck pain" or backache or lumbago or "neck ache" or "spin* pain" or "knee pain" or "hip pain").mp.

OR/4‐8

3 AND 9

(2015* or 2016* or 2017*).em.

10 AND 11

Appendix 9. ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO ICTRP search strategy

ClinicalTrials.gov: Search: (paracetamol OR acetaminophen) AND placebo AND Condition: osteoarthritis.

WHO ICTRP: Title: (paracetamol OR acetaminophen) AND placebo AND Condition: osteoarthritis.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Hip or knee osteoarthritis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain intensity | 9 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Immediate term | 5 | 1686 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.32 [‐5.83, ‐0.81] |

| 1.2 Short term | 7 | 2355 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.23 [‐5.43, ‐1.02] |

| 2 Physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Immediate term | 3 | 1336 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.83 [‐6.41, 2.75] |

| 2.2 Short term | 7 | 2354 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.92 [‐4.89, ‐0.95] |

| 3 Adverse events (AE) | 9 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 AE (any) | 8 | 3252 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.92, 1.11] |

| 3.2 AE (serious) | 6 | 3209 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.73, 2.53] |

| 3.3 AE (withdrawals) | 7 | 3023 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.91, 1.55] |

| 3.4 AE (liver) | 3 | 1237 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.79 [1.94, 7.39] |

| 4 Walking disability | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Immediate term | 1 | 294 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.55 [‐2.09, 0.99] |

| 4.2 Short term | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐2.44, 2.56] |

| 5 Rescue medication | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Patient adherence | 1 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Knee osteoarthritis.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain intensity | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Immediate term | 3 | 1088 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.96 [‐4.19, 0.27] |

| 1.2 Short term | 3 | 813 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.37 [‐4.24, 1.49] |

| 2 Physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Immediate term | 2 | 794 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.33 [‐3.07, 3.74] |

| 2.2 Short term | 3 | 813 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.08 [‐4.66, 2.50] |

| 3 Walking disability | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Immediate term | 1 | 294 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.55 [‐2.09, 0.99] |

| 3.2 Short term | 1 | 25 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐2.44, 2.56] |

Comparison 3. Subgroup analysis: paracetamol 3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain intensity: immediate term | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 ≤ 3.0 g/day | 1 | 56 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐9.2 [‐19.59, 1.19] |

| 1.2 ≥ 3.9 g/day | 4 | 1630 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.98 [‐5.48, ‐0.48] |

| 2 Pain intensity: short term | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 ≤ 3.0 g/day | 2 | 535 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.88 [‐6.41, 0.65] |

| 2.2 ≥ 3.9 g/day | 6 | 1985 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐6.60, ‐2.01] |

| 3 Physical function: immediate term | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 ≥ 3.9 g/day | 3 | 1336 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.83 [‐6.41, 2.75] |

| 4 Physical function: short term | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 ≤ 3.0 g/day | 2 | 535 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.86 [‐6.48, 0.77] |

| 4.2 ≥ 3.9 g/day | 6 | 1985 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.07 [‐5.60, ‐0.54] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Subgroup analysis: paracetamol 3.0 g/day or less versus 3.9 g/day or more, Outcome 3 Physical function: immediate term.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Altman 2007.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, parallel‐group, placebo‐controlled study | |

| Participants |

Population: 483 participants with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee Setting: 47 investigational sites in the US Age: mean 62.2 years, range 40–90 years Numbers: paracetamol 3900 mg/day group: 160; paracetamol 1950 mg/day group: 158; placebo group: 165 Inclusion criteria: presence of symptomatic idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip or knee for a minimum of 6 months with a history of hip or knee pain requiring the use of NSAIDs, paracetamol, or other analgesic on a regular basis (≥ 3 days/week) for ≥ 3 months before the screening visit. History of positive therapeutic benefit with paracetamol use for osteoarthritis pain. Participants must have reported maximum osteoarthritis pain intensity experienced during the 24 hours prior to the baseline visit at a pain level of moderate or moderately severe on a 5‐point Likert scale. Exclusion criteria: taking analgesic therapy for other indications; taking anticoagulants, psychotherapeutic agents, aspirin in daily doses > 325 mg, or statin hypolipidaemic agents in doses that had not been stabilised within 3 months of the screening visit; taking glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, or shark cartilage in doses that had not been stabilised within 6 months of the screening visit; known alcohol abuse, intravenous drug use, drug dependency, or history of significant psychiatric illness in the previous 12 months; received oral corticosteroids within 2 months of screening or intra‐articular or periarticular corticosteroid or hyaluronan injections into the study joint within 6 months of screening; history of gastrointestinal or hepatic disease; clinically apparent inflammation of the study knee joint, secondary osteoarthritis of the study joint, history of acute inflammatory arthritis or pseudogout of the study joint, or medical history, physical examination, or radiographic evidence suggestive of other types of arthritis, collagen vascular disease, or fibromyalgia. |

|

| Interventions | Participants randomly assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups:

Participants instructed to take the assigned study medication every 8 hours for 12 weeks or until study discontinuation. Washout: during the washout period, participants could not take any prescription or non‐prescription NSAID, paracetamol, aspirin, or analgesic in any form. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary efficacy end points were mean change from baseline through 12 weeks. |

|

| Notes | Source of funding: company that produced paracetamol. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "patients were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: unclear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quotes: "double‐blind;" "placebo‐controlled study;" "the placebo caplets were (...) similar in colour, size, and shape to the acetaminophen (...) caplets." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 82/318 withdrawn from paracetamol groups (27 due to "lack of efficacy"); 54/165 withdrawn from control group (34 due to "lack of efficacy"). No description of reasons for dropout given. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol available and all outcomes that were of interest in the study were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The trial was supported by a pharmaceutical company. |

Amadio 1983.

| Methods | Cross‐over, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants |

Population: 25 participants with knee osteoarthritis diagnosis by image and clinical symptoms Age: median 64 years, range 43–80 years Inclusion criteria: X‐ray findings of typical bilateral osteoarthritis of the knee (i.e. narrowing of the joint space and osteophyte formation) within 3 months of entry into the study. Required to have ≥ 1 of: pain at rest, tenderness on pressure, swelling, and heat. Exclusion criteria: any concomitant illness that could affect the knees, such as rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever, positive rheumatoid factor > 1 to 40, very high sedimentation rates, gouty arthritis, periarteritis nodosa, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, disseminated lupus erythematosus (preferably with negative antinuclear antibodies), psoriasis, syphilitic neuropathy, ochronosis, or significant primary metabolic bone disease; pregnant women; known allergy to paracetamol; and severe mechanical instability of, or evidence of recent acute trauma to, the knees. |

|

| Interventions | Participants randomly assigned to 1 of 2 treatment groups:

Washout: to minimise the effects of previous medication upon the assessment of paracetamol therapy, all possibly interfering drug regimens were discontinued prior to the study. Steroid therapy (including intra‐articular injection) was terminated at 6 weeks, NSAIDs ≥ 2 weeks, and salicylates ≥ 48 hours prior to study entry. Follow‐up: 4 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "By randomization, half of the patients received acetaminophen [paracetamol] and half placebo." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: unclear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "double‐blind;" "placebo‐crossover study;" "identically‐appearing placebo." Comment: probably done. |