Abstract

Background:

It is not known whether the human anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is susceptible to fatigue failure as a result of repetitive loading, or whether certain knee morphologies increase that risk.

Hypotheses:

The number of knee loading cycles required to fail an ACL by fatigue failure is unaffected by the magnitude of the external load delivered to the knee joint. Furthermore, neither gender, ACL cross-sectional area nor lateral tibial slope affect the number of loading cycles to ACL failure.

Study Design:

Controlled laboratory study

Methods:

Knee pairs from 10 cadaveric donors (5 female) of similar age, height, and weight were imaged with 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging to measure lateral tibial slope and ACL cross-sectional area. One knee from each pair was then subjected to the repeated application of a three-times body weight (3*BW) loading, while the other knee was subjected to a 4*BW loading, both involving impulsive compression, knee flexion moment and internal tibial torque combined with realistic trans-knee muscle forces. The resulting 3-D tibiofemoral kinematics and kinetics were recorded, along with ACL relative strain, and quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius muscle forces. The loading cycle was repeated until the ACL ruptured, a 3-mm increase in cumulative anterior tibial translation occurred, or a minimum of 50 trials was reached.

Results:

Eight of 10 knees failed under the 4*BW loading (mean (SD) cycles to failure: 21 (18)), while five of 10 knees failed under the 3*BW loading (mean (SD) cycles to failure: 52 (10)). Four knees exhibited a 3-mm increase in anterior tibial translation, seven knees developed partial or complete visible ACL tears, and two knees developed complete ACL tibial avulsions. A Cox regression showed that the number of cycles to ACL failure was influenced by the simulated landing force (p = 0.012) and ACL cross-sectional area (p = 0.022). Gender and lateral tibial slope did not influence the number of cycles to ACL failure.

Conclusion:

The human ACL is susceptible to fatigue failure when pivot landings of 3*BW or more load the knee repeatedly within a short time span. ACLs of smaller cross-sectional area are at greater risk for this type of failure.

Clinical Relevance:

The results show that the human knee can only withstand a certain number of 3*BW or more jump loading cycles within a short time period before the ACL will fail. Therefore limiting the increase in the number and severity of pivot landing maneuvers performed over a week of training would make sense from an injury prevention viewpoint.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, rupture, fatigue life, pivot landing, morphology

Introduction

Current research into anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury mechanisms fails to explain why an athlete can perform a jump and/or pivot maneuver many times without injury, yet suddenly rupture their ACL while apparently performing a similar maneuver one more time. To date ACL injury video analysis has concentrated on the circumstances at the time of injury as being the cause of the ACL injury6, 39. However, the ACL loading history of ACL loading could also be a major factor to consider. Presently, we do not know if the ACL will fail under repetitive loading as a result of ligament fatigue failure37. Tissue fatigue failures resulting from repetitive loading have been identified as the cause of tibial stress fractures in military recruits13 and elbow ligament failures in Little League pitchers20. Repetition of a maneuver is fundamental to skill acquisition, athletic training, and performance in competition. It is possible that repeated loading can cause an ACL to fail suddenly under routine landing conditions, especially when muscle fatigue occurs.

Athletes usually perform similar movements hundreds, if not thousands, of times before an ACL injury occurs. For example, professional soccer players in the FA Premier League average 727 turning or swerving maneuvers per match3. Moreover, similar movements can result in a wide variation of peak joint loads because of the many different combinations of muscle forces that counteract the external loads14. Our working hypothesis is that under peak knee joint loads known to induce large ACL strains, the ACL will fail after the repeated application of a joint loading cycle that did not cause ACL failure in earlier loading cycles.

Animal and cadaveric tensile testing has shown that passive collagenous structures like ligaments are susceptible to fatigue failure: the larger the tensile stress applied repeatedly to the structure, the fewer the number of loading cycle before it will fail32, 38, 40, 43. The damage accumulation over the course of a fatigue failure reduces a ligament’s modulus of elasticity39, thereby placing it in a susceptible state. This may be especially true for females, given their smaller ACL diameter4, 9 and volume5, and smaller modulus of elasticity4. Since a greater lateral tibial slope and a smaller ACL cross-sectional area are associated with increased peak ACL strain during a simulated pivot landing19, we also hypothesize that these factors will reduce the number of loading cycles until a dynamic maneuver fails the ACL.

The objective of this study, therefore, was to determine whether the ACL exhibits fatigue behavior under strenuous repetitive simulated pivot landings. Demonstration of a fatigue failure injury mechanism could represent a paradigm shift in ACL injury mechanism research because it would explain why athletes who repeatedly perform the same maneuver without incident suddenly rupture an ACL. Using matched paired knees, a knee from each pair was tested at 4*BW or 3*BW loading to test the primary null hypothesis that the number of knee loading cycles before an ACL fails is unaffected by the magnitude of the externally applied load. We also tested the secondary null hypotheses that the number of knee loading cycles to ACL failure is unaffected by gender, ACL cross-sectional area, or lateral tibial slope.

Materials and Methods

Ten pairs of human lower extremities (5 females) from donors of similar age, height and weight (5 female pairs, 5 male pairs; mean (SD) age: 53(7) years, height: 174(9) cm, body mass: 69(9) kg) were acquired from <<Blinded for AJSM Review>>. The specimens were screened to eliminate a history of lower extremity surgery, trauma or degenerative changes, as evidenced by visual scars or deformities of the knee joint. The specimens were harvested and dissected, keeping the muscle tendons of the quadriceps, medial and lateral hamstrings, and medial and lateral gastrocnemius intact, as well as the ligamentous capsular structures. The distal femur and proximal tibia and fibula were cut 20 cm from the knee joint line. Specimens were stored frozen at −20° C and were thawed at room temperature prior to imaging and testing.

Prior to testing, all twenty knees were imaged with a 3-Tesla T2-weighted MR scan (Philips Healthcare 3T scanner [Best, the Netherlands], 3D proton-density sequence; repetition time/echo time, 1000/35 milliseconds; slice thickness, 0.7 mm; pixel spacing, 0.35 mm x 0.35 mm; field of view, 330 mm). The scans were viewed and measured in OsiriX (v3.9, open source, www.osirix-viewer.com). ACL cross-sectional area was measured by outlining the circumference at 30% ligament length from the tibial origin with an oblique-axial view perpendicular to the ligament19. This location along the ligament is where the DVRT was placed on the ligament during testing. Lateral tibial slope was measured ad modam Hashemi et al.15: two anteroposterior lines were drawn 10 cm and 15 cm from the most proximal point on the central axis image, defined as the slice were the tibial attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament and the intercondylar eminence were visible. The midpoints of the anteroposterior lines were connected to define the tibial proximal anatomic axis. Lateral tibial slope was measured at the tibial center of articulation on the lateral tibial plateau, and was defined as the angle between a line perpendicular to the tibial proximal anatomic axis and a line fit to the posterior-inferior subchondral bone surface.

Following imaging, the distal femur and proximal tibia and fibula were potted in a 7.8-cm diameter PVC cylinder filled with PMMA. The ends of the potted bones were placed into aluminum housings within an established testing apparatus19, 26, 41 capable of impulsively simulating a pivot landing with loads up to five-times body weight (5*BW) compression force with an added flexion moment (up to 120 Nm) and internal tibial torque (up to 45 Nm). This combination of loading vectors induces larger ACL strains than other combinations26. The experimental design randomly assigned one knee to a 3*BW simulated pivot landing and the paired knee to a 4*BW pivot landing. By testing the two knees from a given subject at different landing intensities, this matched-pairs design takes advantage of the fact that intra-subject variability is usually less than inter-subject variability in detecting whether the number of cycles to ACL failure differs between the knees. The drop height and drop weight were adjusted to apply the desired magnitude of compressive force to the specimen. Each trial was initiated by dropping a weight (‘W’) onto an impact rod in series with a torsional device (‘T’) as the loads applied to the knee are monitored with load cells (‘L’) on the distal femur and proximal tibia (Figure 1). The angle of the struts within the torsional device controls the gain between the applied impulsive compressive force and impulsive internal tibial torque.

Figure 1.

The in vitro testing apparatus. A drop weight (‘W’) results in an impulsive compressive force posterior to the knee joint that also induces a knee flexion moment. A torsional device (‘T’) added an internal tibial torque component to the compound loading. Load cells (‘L’) monitor the 3-D input and reaction forces and moments at the proximal tibial and distal femur. The quadriceps (‘Q’), hamstrings (‘H’), and gastrocnemius (‘G’) muscles were pre-tensioned prior to each trial, placing the knee initially at 20° knee flexion. A DVRT (inset) measured relative strain on the anteromedial bundle of the ACL during the impact. [Figure modified from Oh et al., Am J Sports Med, 2012]

Tibiofemoral kinematics were measured at 400 Hz using optoelectronic marker triads on the proximal tibia and distal femur (Optotrak Certus, Northern Digital, Inc., Waterloo, Ontario, Canada). A 3-D digitizing wand was used to define standard anatomical landmarks on the knee joint in order measure relative and absolute changes in tibiofemoral 3-D translations and rotations. Specifically, anterior tibial translation and internal tibial rotation were measured relative to each trial (referred to as a relative measurement) as well as the first pivot trial (referred to as a cumulative measurement). Two six-axis load cells (MC3A-1000, AMTI, Watertown, MA) were used to monitor the input and the reaction forces and moments applied to the proximal tibia and distal femur. Nylon string (stiffness: 250 N/mm for male knees and 200 N/mm for female knees, to account for gender difference in quadriceps tensile stiffness12) served as a muscle-equivalent for the pretensioned the quadriceps (‘Q’: 180 N), hamstrings (‘H’: 70 N each), and gastrocnemius (‘G’: 70 N each) muscles.

The knee was placed at an initial knee flexion angle of 20° prior to each trial. Each muscle equivalent was located in series with a cryo-clamp frozen onto its tendon with liquid nitrogen, as well as a uniaxial load cell (TLL-1K and TLL-500, Transducer Techniques, Inc., Temecula, CA). Peak relative strain on the anteromedial (AM-) bundle of the ACL was monitored with a differential variable reluctance transducer (DVRT) (3-mm stroke length, MicroStrain, Inc., Burlington, VT) installed at a location one-third of the length of the ligament from its tibial insertion to prevent impingement on the femoral intercondylar notch. The initial DVRT length used to calculate strain was relative to the DVRT’s inter-barb length at the beginning of each trial (peak AM-ACL relative strain) and the first pivot trial (peak AM-ACL cumulative strain). The tibiofemoral kinetics, muscle forces, and strain data were measured at 2 kHz.

The testing protocol began with five preconditioning non-pivot trials of compression + flexion moment. During the preconditioning trials, the drop height and drop weight were adjusted to the target compressive force of 3*BW or 4*BW by the final non-pivot trial. These trials also minimized hysteresis effects prior to the pivot trials. After five non-pivot trials, the drop height and drop weight remained constant in order to ensure the same energy was applied to the knee. The torsional device was activated to apply, on average, 30 Nm internal tibial torque for the 3*BW and 35 Nm internal tibial torque for the 4*BW test loads, in addition to compressive force and a knee flexion moment (78 and 97 Nm, respectively), simulating a pivot landing. Typically, there was a one minute break between loading trials to reset the muscle forces and initial knee flexion angle. However, every 20 – 30 trials a three to five minute interval had to be taken to refreeze the rectus femoris tendon clamp using liquid nitrogen. The pivot landings were repeated until (a) gross ligament failure, (b) a 3-mm increase in the cumulative anterior tibial translation, or (c) a minimum of 50 trials were performed. Following testing, the ACL was visually inspected for macroscopic failure of the AM as well as posterolateral (PL) bundles.

An ACL failure was confirmed if there was visual evidence of yielding on the real time plot of ACL strain against time of a complete or partial ACL tear, an ACL avulsion occurred, or cumulative anterior tibial translation increased by 3 mm. The primary hypothesis that external loading will not affect the number of cycles to ACL failure was tested using 20 matched pair knees: one knee from each pair was externally loaded at 3*BW or 4*BW. The hypothesis was tested statistically using a Cox regression model with shared frailty in Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to predict the number of cycles to ACL failure using simulated landing force as a covariate. Gender, ACL cross-sectional area, and lateral tibial slope were included as covariates in the Cox regression to test the secondary hypotheses. A tertiary analysis longitudinally compared anterior tibial translation and internal tibial rotation throughout the experiment using a linear mixed model. The mixed model analyzed the first pivot trial and final pivot trial (using both the relative and cumulative measurement) and treated ligament status (coded as 0 = intact and 1 = failed) as a fixed factor. A random intercept was utilized for each subject (coded by their donor ID) to account for differences in anterior tibial translation between donors. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant for the primary and secondary analysis.

Results

Eight of 10 knees tested under the 4*BW impact loading failed and the mean (SD) number of cycles to ACL failure was 21 (18) cycles. Under the 3*BW impact loading, however, five of 10 knees failed, and did so in 52 (10) cycles. The mean (SD) landing force and internal tibial torque were 4.3 (0.4) BWs and 34.5 (7.3) Nm for the higher impact landing and 3.5 (0.3) BWs and 29.8 (5.4) Nm for the lower impact landing. Of the 13 failed knees, there were one complete ACL tear, six partial ACL tears, two ACL avulsions, and four permanent elongations of the ACL (i.e., 3 mm increase in cumulative anterior tibial translation) (Table 1). Post-testing images from all 10 matched-pair knees are provided in Supplemental Text 1.

Table 1.

Injury description and applied loading for the 20 study donors

| ID | Leg | Landing Force (BW) | Internal Tibial Torque (Nm) | Injury Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M32381 | L | 3.6 (0.4) | 32.3 (1.4) | Permanent elongation* |

| R | 4.5 (0.1) | 43.2 (1.0) | Partial tear PL bundle near (F) | |

| M61535 | L | 4.8 (0.1) | 39.2 (0.8) | Did not fail |

| R | 3.9 (0.1) | 33.2 (1.3) | Did not fail | |

| M33449 | L | 3.8 (0.1) | 38.8 (1.0) | Did not fail |

| R | 4.7 (0.1) | 42.7 (0.7) | Permanent elongation* | |

| M33812 | L | 4.1 (0.1) | 34.0 (2.2) | Tibial avulsion |

| R | 3.6 (0.1) | 30.6 (1.8) | Partial tears of PL bundle near (F) and AM bundle near (T) | |

| M72780 | L | 3.9 (0.1) | 43.1 (2.2) | Did not fail |

| R | 3.1 (0.1) | 36.5 (0.4) | Did not fail | |

| F42263 | L | 3.5 (0.1) | 25.9 (1.6) | Permanent elongation* |

| R | 4.6 (0.2) | 28.1 (0.9) | Partial tear PL bundle (F) | |

| F33913 | L | 4.2 (0.3) | 23.0 (0.5) | Partial tear PL bundle (F) |

| R | 3.4 (0.1) | 22.6 (0.3) | Partial tear PL bundle near (F) | |

| F34015 | L | 3.3 (0.1) | 24.3 (1.0) | Did not fail |

| R | 4.1 (0.3) | 27.6 (0.8) | Partial tear PL bundle near (M) | |

| F11442 | L | 3.8 (0.2) | 34.0 (1.9) | Complete tear (M) |

| R | 3.1 (0.3) | 28.3 (1.4) | Permanent elongation* | |

| F34090 | L | 4.0 (0.2) | 29.8 (1.4) | Tibial avulsion |

| R | 3.2 (0.1) | 25.9 (1.1) | Did not fail |

Note: Permanent ACL elongation was defined as a 3-mm increase in cumulative anterior tibial translation from the first pivot trial. Landing force and internal tibial torque are displayed as mean (SD).

Abbreviations: BW – normalized to body weight; (F) – Femur; (T) – Tibia; (M) – Mid-substance.

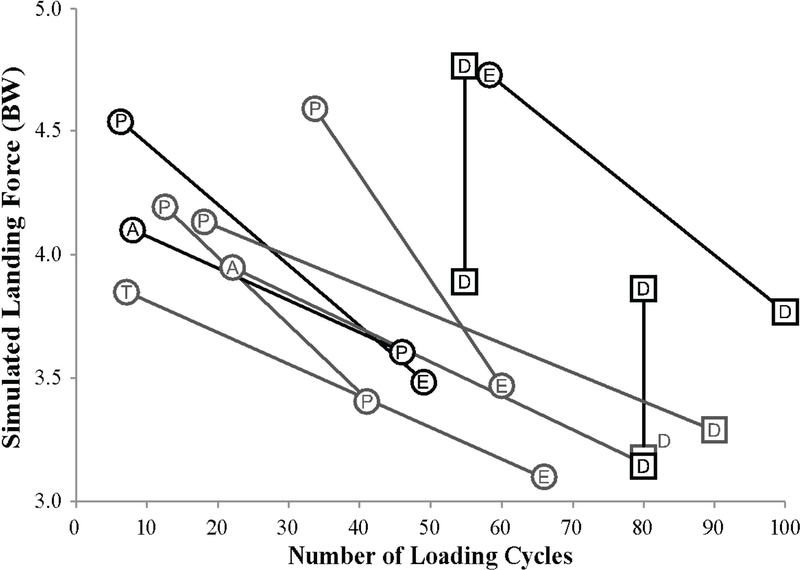

The primary hypothesis was rejected because a greater simulated landing force (Figure 2) was significantly associated with fewer loading cycles to ACL failure (Wald χ2 = 10.06; p = 0.039; Table 2). The secondary analysis was rejected for the effect of ACL cross-sectional area because a smaller ACL cross-sectional area was significantly associated with fewer loading cycles to ACL failure. Neither lateral tibial slope nor gender, however, proved significant predictors of the number of cycles to ACL failure. The mean (SD) ACL cross-sectional area and lateral tibial slope were 35.5 (11.2) mm2 and 8.7 (3.3)°, respectively, for male knees and 31.4 (8.7) mm2 and 9.9 (2.8)°, respectively, for female knees. Importantly, if the Cox regression analysis was rerun using ACL rupture as the sole failure criterion, the landing force (p = 0.039) and ACL cross-sectional area (p = 0.037) still remained significant predictors of the number of loading cycles to failure.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot showing the simulated landing force (as recorded as the compressive force on the femoral load cell) vs. the number of loading cycles for the ACL. A circle represents an ACL failure. A square represents a knee with an intact ACL at the conclusion of testing. The black markers are male knees, the gray markers are female knees, and the matched pair of each donor is connected with a line. Abbreviations within the marker denote the type of ACL failure: A – tibial avulsion; P – partial ACL tear; T – complete ACL tear; E – permanent elongation of the ACL determined by a 3-mm increase in cumulative anterior tibial translation. D denotes a knee which did not fail.

Table 2.

Cox regression results for twenty knees with shared frailty term (theta) to control for matched-pairs.

| Regressor | Hazard Ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landing Force | 32.27 | (2.13, 487.7) | 0.012* |

| Gender | 0.95 | (0.05, 19.7) | 0.98 |

| ACL CSA | 0.63 | (0.42, 0.93) | 0.022* |

| LTS | 0.90 | (0.55, 1.45) | 0.67 |

| Theta | 2.97 | 0.006* |

Abbreviations: CSA – cross-sectional area; LTS: lateral tibial slope.

Asterisk indicates significant p-value

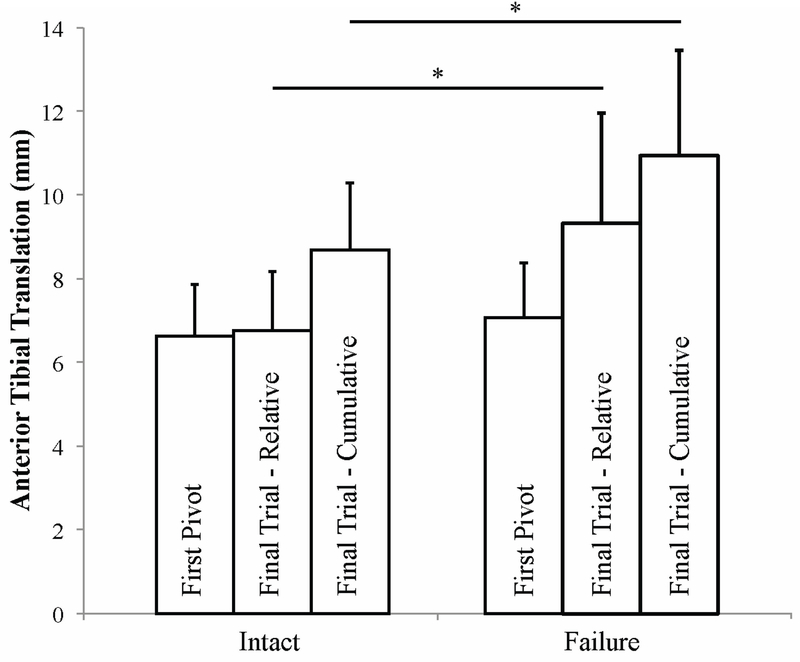

The tertiary analysis demonstrated that anterior tibial translation between intact and failed knees did not differ during the first pivot trial (Figure 3, p = 0.386). The failed knees showed greater relative (p = 0.027) and cumulative (p = 0.046) anterior tibial translation than the intact knees during the final pivot trial. Internal tibial rotation did not differ between intact or failed knees (Figure 4, first pivot trial: p = 0.713; final pivot trial, relative: p = 0.540; final pivot trial, cumulative: p = 0.679). The cumulative increases of anterior tibial translation and internal tibial rotation for each knee pair are illustrated in Supplemental Text 2.

Figure 3.

Anterior tibial translation for knees with an intact or failed ACL for the first and final pivot trial tested. For the final trial, anterior tibial translation is the change in anterior tibial translation relative to the tibial origin at the beginning of the final trial (relative) as well as the beginning of the first pivot trial (cumulative). Asterisk indicates a p-value less than 0.05.

Figure 4.

Internal tibial rotation for knees with an intact or failed ACL for the first and final pivot trial tested. For the final trial, internal tibial rotation is the change in internal tibial rotation relative to the tibial origin at the beginning of the final trial (relative) as well as the beginning of the first pivot trial (cumulative).

The mean (SD) non-pivot peak AM-ACL relative strain was 3.2 (1.6) % for intact ACLs and 4.5 (2.5) % for failed ACLs. After the first pivot trial, peak AM-ACL relative strain increased to 6.7 (3.4) % and 7.1 (3.8) % for intact and failed knees, respectively. By the final testing trial, peak AM-ACL relative and cumulative strain for intact knees were 4.7 (2.9) % and 6.3 (5.0) %, respectively. For knees with failed ACLs, peak AM-ACL relative and cumulative strain were 11.0 (12.2) % and 11.9 (11.7) %, respectively. There was a trend towards a negative relationship between peak AM-ACL cumulative strain and the number of cycles to ACL failure in the 13 failed knees (ρ = −0.455, p = 0.118) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A scatterplot of peak AM-ACL cumulative strain vs. the number of cycles to ACL failure for the 13 knees, which underwent a complete tear, partial, tear, tibial avulsion, or permanent elongation. A linear fit to the scatterplot, with its associated Pearson correlation and p-value, is indicated with a dashed line.

Discussion

The fact that athletes perform the same cutting or pivoting maneuver hundreds, if not thousands, of times a season, means that the loading history of the ACL is potentially relevant in determining whether an injury occurs. We believe that this is the first study to test and provide support for the hypothesis that the human ACL is susceptible to low-cycle fatigue failure. Depending upon the magnitude of the load, the results show that the fatigue life of a human ACL can be less than 60 severe loading cycles. A larger landing force, as well as a smaller ACL cross-sectional area, were both predictive of fewer cycles to ACL failure. The finding that ACL cross-sectional area was predictive of the number of cycles to failure should not be surprising. For a given load, a higher ligament tensile stress (tensile force per unit area) should result in the earlier failure of an ACL of smaller cross-sectional area, because the number of cycles until failure is known to be inversely proportional to the repetitive tensile stress placed on that material36.

Collagenous structures such as ligament and tendon are known to be susceptible to fatigue failure under repetitive loading. For example, rabbit medial collateral ligament38, human Achilles tendon43, wallaby tail tendons40, and human extensor digitorium longus tendons32 all demonstrate an inverse relationship between applied tensile stress and the number of cycles to failure. It is the damage accumulation associated with cyclic loading that causes ligaments to fail due to fatigue rather than creep38. And a positive feedback cycle has been noted: the higher the tensile cyclic stress applied to the ligament, the more rapidly microdamage accumulates due to a reduction in the modulus of elasticity39.

Sex-based differences in structural and mechanical properties of the ACL could influence fatigue behavior because the human female ACL is 21–34% smaller in cross-sectional area4, 9, 17–27% smaller in ACL volume4, 5 and has a 22% lower tensile modulus of elasticity than the male ACL4. Therefore, for a given external loading magnitude in size-matched individuals, the female ACL will systematically experience greater stress than the male ACL. With a lower ultimate tensile stress4, the female ACL will likely experience a fatigue failure in fewer loading cycles than the male ACL. Following ACL reconstruction, the gender difference in re-injury rates is may be lessened by using similarly sized 10-mm patellar tendon grafts34, eliminating the gender discrepancy in ACL size and stress. While gender was not significant in the present study, ACL cross-sectional area was a significant predictor of the cycles to ACL failure. Lateral tibial slope has been previously identified as a predictor of ACL strain19 and ACL injury risk15 because the greater the slope, the greater the tensile force as well as the tensile stress placed on the ACL35. Tibial slope and gender were not significant predictors of the number of cycles until ACL failure in this study, most likely due to the modest sample size.

Our study demonstrates that the ACL fails under repetitive simulated landings involving combined impulsive compression, flexion and internal tibial torque loads with realistic muscle forces. A previous study failed the ACL under dynamic internal tibial torque and quasi-statically applied compressive force without muscle loads at 30 degrees flexion22, 23. That study failed the ACL with internal tibial torques ranging from 10 to 50 Nm and four partial tears of the posterolateral bundle occurred near the femur, along with three tibial avulsions. The current study utilizes a more physiologic loading scenario with muscle forces along with a focus on the effects of repetitive loading. Both the present results and Meyer et al.22 strongly suggest that the posterolateral bundle of the ACL may be compromised during a pivot landing with internal tibial torque.

The functional anatomy of the ACL can help explain why greater damage occurs to the posterolateral bundle during pivot landings with the knee near full extension. The ACL is often described functionally as a two-bundle ligament; the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles display independent tension patterns6, 10, 29. The posterolateral bundle carries greater loads near extension2, 11 and contributes more resistance to axial tibial rotation than anterior tibial translation6 due to its anatomical location and orientation1. An isolated tear of the posterolateral bundle will not produce a detectable increase in anterior tibial translation under an anterior tibial load16. Anterior tibial translation will increase under an applied load of internal tibial torque and knee abduction moment45. Therefore, since the posterolateral bundle resists rotational loads near full knee extension, it may be more vulnerable to injury during a pivot landing.

Our results show that knee loading magnitude affected ACL fatigue life with or without the knees that demonstrated a 3-mm increase in anterior tibial translation in the failure subset. Clinically, a 3-mm increase in anterior tibial translation is an accepted sign of ACL failure regardless of whether the ACL appears partially or completely torn7, 8. There can be considerable disruption and disorganization of collagen fibrils in human ACL at ultimate tensile failure without macroscopic tearing18. For example, in rabbit medial collateral ligament, a 10% strain will cause disruption of thin collagen fibers without macroscopic tearing; disruption of the thick collagen fibers will occur by 20% strain44. The macroscopic appearance of an ACL does not necessarily reflect the functional capacity or the extent of elongation in the ligament25. Submaximal failures of ligament will affect viscoelastic properties, including a reduction in initial stiffness as well as viscosity27. Furthermore, the load-displacement behavior of the ligament’s toe region will be elongated28, 31, which may yield greater laxity during daily activities. There will be an overall reduction in the modulus of elasticity and ultimate stress31, placing the ligament at risk for failure. Since many submaximal elongation failures occurred at the lower simulated landing forces, partial or complete tears of these ligaments could occur when landing forces are increased, especially if more loading cycles are added.

The strengths of this study design were the use of matched-paired knees from donors of similar age, height, and weight to investigate the potential of ligament fatigue failure. The realistic applied external and muscle forces during the simulated pivot landing, the realistic ACL strains and strain rates that were induced, and the blinded observer for measuring ACL cross-sectional area and lateral tibial slope from MRI scans are all important factors to consider. Also, the matched pair design reduced the role of inter-subject variability.

Although the study has limitations, these should not affect the overall study findings. First, the insertion of the two DVRT barbs could potentially have initiated very minor failure in the AM bundle. This concern is mitigated by the fact that the majority of the macroscopic ACL damage occurred remote to either DVRT barb location. Second, the macroscopic tearing and/or microstructural damage of the PL bundle combined with sub-failure AM-ACL relative strain suggests that the PL bundle is loaded more than the AM bundle during pivot landings at 20° knee flexion. This is contrary to the finding that AM bundle strain is indicative of ACL force21. Clinically, anterior tibial translation is the most reliable measurement of an ACL’s status. While some knees with a failed PL bundle showed no increase in peak AM-ACL strain, others knees showed a large increase in peak AM-ACL strain. We speculate that the AM bundle fibers were not tensioned by the loading to the same extent as the PL bundle fibers. However, strain on the PL bundle could not be measured because the DVRT would impinge on the medial notch wall of the lateral femoral condyle in an extended knee.

Since ACL stress could not be measured without physically altering the ligament or its insertions, we used the external load applied to the knee as a surrogate measurement of ACL stress. Furthermore, the limb donors were older than the adolescent and young adult populations who are most at risk for ACL injury33. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the injury patterns observed in our in vitro testing apparatus may differ from those in younger donors. We would expect younger donors to withstand more cycles prior to reaching their fatigue limit because their ultimate tensile load should be 40% higher than older donors42. Furthermore, repeated in vivo landings can also induce muscle fatigue, an effect that was not considered in the present experiments, but could be incorporated in future experiments with this experimental setup.

Finally, changing the time interval between loading cycles might affect ACL fatigue life. As described in the Methods, we typically performed one trial per minute, with an extended break of three-to-five minutes when refreezing the rectus femoris tendon. While a few knees showed ligament recovery in the measurements of anterior tibial translation following the refreezing interval, these same knees quickly reached and then exceeded the pre-freezing level of anterior tibial translation once repeated loading was resumed. Similar recovery behavior has been reported in cyclically strained tendon during a rest interval of 30 minutes17. However, future investigations are warranted to assess whether lengthening the time between loadings cycles would positively affect the ligament fatigue life. Furthermore, improvements to the testing setup could be made to reduce the tendon re-freezing time.

Despite these limitations, this study provides new insight by demonstrating that the ACL is susceptible to fatigue failure in vitro. Our estimate of ACL fatigue life (i.e., the number of loading cycles to failure) is likely conservative because the tissue adaptation and remodeling that occur in vivo over several months would extend ACL fatigue life beyond that measured here. The potential for an acute in vivo ACL repair response to the damage is an unknown parameter. But since the ACL has a poor blood supply24, it is unlikely that any meaningful repair can be accomplished if 60 severe loading cycles were to be applied within a time frame as short as an hour, a day or even a week. Hence the present in vitro results predict that the ACL will fail in vivo whenever enough severe loading cycles are applied within a relatively short time frame, especially if this represents a short-term increase in the severity or number of loading cycles beyond a status quo to which the ligament has adapted over a longer time period. Lengthening the rest interval between loading cycles could help decrease cumulative ACL strain30 thereby increasing the fatigue life of the ACL. But based on our findings, it would make sense to limit the increase in the number and severity of pivot landing maneuvers performed a short time frame such as a week of training.

We note that ACL fatigue failure behavior encompasses the possibility of a “single event” injury because the traction force on the ACL only has to exceed its ultimate tensile strength for it to fail in the first loading cycle. However, reducing the magnitude of that force will allow the ACL to survive for additional loading cycles before failing. If the repeated ACL load lies below a certain threshold, such as that induced during walking and running, then ACL failure is not likely to occur during that activity. Clearly, further research is needed to understand the many factors affecting the fatigue life of the ACL, both in vitro and in vivo.

Supplementary Material

What is known about the subject?

Attention is usually focused on the maneuver being performed by an athlete when an ACL ruptures. However, this approach fails to consider the loading history of the ACL. Sudden structural failure under repeated loading is characteristic of a tissue fatigue failure. Since other collagenous structures exhibit fatigue behavior, we hypothesized this to also be true of the ACL. Given that ACL cross-sectional area and lateral tibial slope both modulate peak ACL strain under pivot landing scenarios, these variables could plausibly affect the risk of ACL fatigue failure.

What this study adds to existing knowledge?

This is the first study to demonstrate that the loading history of the ACL is important: the larger the loads, the fewer the loading cycles an ACL can withstand over a short time span before failure, especially ACLs of smaller cross-section. This tissue fatigue behavior could help explain why an ACL can rupture during an unremarkable athletic maneuver performed many times before without incident. Based on these results, it would seem prudent to limit the number of times that the ACL is subjected to large forces within a short time span.

Acknowledgments

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: The University of Michigan has filed a provisional United States patent application entitled “Footwear and Method to Reduce ACL Injury” naming all 3 authors. Funding was provided by United States Public Health Service grant R01 AR054821 and a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship (D.B.L.).

References

- 1.Amis AA. The functions of the fibre bundles of the anterior cruciate ligament in anterior drawer, rotational laxity and the pivot shift. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(4):613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amis AA, Dawkins GP. Functional anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament. Fibre bundle actions related to ligament replacements and injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(2):260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomfield J, Polman R, O’Donoghue P. Physical demands of different positions in FA Premier League soccer. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2007;6(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandrashekar N, Mansouri H, Slauterbeck J, Hashemi J. Sex-based differences in the tensile properties of the human anterior cruciate ligament. J Biomech. 2006;39(16):2943–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhari AM, Zelman EA, Flanigan DC, Kaeding CC, Nagaraja HN. Anterior cruciate ligament-injured subjects have smaller anterior cruciate ligaments than matched controls: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(7):1282–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christel PS, Akgun U, Yasar T, Karahan M, Demirel B. The contribution of each anterior cruciate ligament bundle to the Lachman test: a cadaver investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Sachs R, Malcom L. Instrumented measurement of anterior knee laxity in patients with acute anterior cruciate ligament disruption. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(6):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFranco MJ, Bach BR Jr., A comprehensive review of partial anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dienst M, Schneider G, Altmeyer K, et al. Correlation of intercondylar notch cross sections to the ACL size: a high resolution MR tomographic in vivo analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(4):253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furman W, Marshall JL, Girgis FG. The anterior cruciate ligament. A functional analysis based on postmortem studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(2):179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriel MT, Wong EK, Woo SL, Yagi M, Debski RE. Distribution of in situ forces in the anterior cruciate ligament in response to rotatory loads. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(1):85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granata KP, Wilson SE, Padua DA. Gender differences in active musculoskeletal stiffness. Part I. Quantification in controlled measurements of knee joint dynamics. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2002;12(2):119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greaney RB, Gerber FH, Laughlin RL, et al. Distribution and natural history of stress fractures in U.S. Marine recruits. Radiology. 1983;146(2):339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson AM, Padua DA, Troy Blackburn J, Prentice WE, Hirth CJ. Muscle activation during side-step cutting maneuvers in male and female soccer athletes. J Athl Train. 2008;43(2):133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashemi J, Chandrashekar N, Mansouri H, et al. Shallow medial tibial plateau and steep medial and lateral tibial slopes: new risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hole RL, Lintner DM, Kamaric E, Moseley JB. Increased tibial translation after partial sectioning of the anterior cruciate ligament. The posterolateral bundle. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(4):556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubbard RP, Chun KJ. Mechanical responses of tendons to repeated extensions and wait periods. J Biomech Eng. 1988;110(1):11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy JC, Hawkins RJ, Willis RB, Danylchuck KD. Tension studies of human knee ligaments. Yield point, ultimate failure, and disruption of the cruciate and tibial collateral ligaments. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(3):350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipps DB, Oh YK, Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM. Morphologic characteristics help explain the gender difference in peak anterior cruciate ligament strain during a simulated pivot landing. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(1):32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Osinski ED. Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markolf KL, Willems MJ, Jackson SR, Finerman GA. In situ calibration of miniature sensors implanted into the anterior cruciate ligament part II: force probe measurements. J Orthop Res. 1998;16(4):464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer EG, Baumer TG, Slade JM, Smith WE, Haut RC. Tibiofemoral contact pressures and osteochondral microtrauma during anterior cruciate ligament rupture due to excessive compressive loading and internal torque of the human knee. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1966–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer EG, Haut RC. Anterior cruciate ligament injury induced by internal tibial torsion or tibiofemoral compression. J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3377–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray MM, Martin SD, Martin TL, Spector M. Histological changes in the human anterior cruciate ligament after rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(10):1387–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noyes FR, DeLucas JL, Torvik PJ. Biomechanics of anterior cruciate ligament failure: an analysis of strain-rate sensitivity and mechanisms of failure in primates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(2):236–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh YK, Lipps DB, Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM. What strains the anterior cruciate ligament during a pivot landing? Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):574–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panjabi MM, Moy P, Oxland TR, Cholewicki J. Subfailure injury affects the relaxation behavior of rabbit ACL. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1999;14(1):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panjabi MM, Yoldas E, Oxland TR, Crisco JJ 3rd. Subfailure injury of the rabbit anterior cruciate ligament. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(2):216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen W, Zantop T. Partial rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(11):1143–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pioletti DP, Rakotomanana LR. On the independence of time and strain effects in the stress relaxation of ligaments and tendons. J Biomech. 2000;33(12):1729–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Provenzano PP, Heisey D, Hayashi K, Lakes R, Vanderby R, Jr. Subfailure damage in ligament: a structural and cellular evaluation. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(1):362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schechtman H, Bader DL. In vitro fatigue of human tendons. J Biomech. 1997;30(8):829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shea KG, Pfeiffer R, Wang JH, Curtin M, Apel PJ. Anterior cruciate ligament injury in pediatric and adolescent soccer players: an analysis of insurance data. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(6):623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(2):246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelburne KB, Kim HJ, Sterett WI, Pandy MG. Effect of posterior tibial slope on knee biomechanics during functional activity. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(2):223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shigley JE, Mitchell LD. Mechanical Engineering Design. 4 ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shultz SJ, Schmitz RJ, Nguyen AD, et al. ACL Research Retreat V: an update on ACL injury risk and prevention, March 25–27, 2010, Greensboro, NC. J Athl Train. 2010;45(5):499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thornton GM, Schwab TD, Oxland TR. Cyclic loading causes faster rupture and strain rate than static loading in medial collateral ligament at high stress. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2007;22(8):932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornton GM, Schwab TD, Oxland TR. Fatigue is more damaging than creep in ligament revealed by modulus reduction and residual strength. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35(10):1713–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang XT, Ker RF, Alexander RM. Fatigue rupture of wallaby tail tendons. J Exp Biol. 1995;198(Pt 3):847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Withrow TJ, Huston LJ, Wojtys EM, Ashton-Miller JA. The relationship between quadriceps muscle force, knee flexion, and anterior cruciate ligament strain in an in vitro simulated jump landing. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(2):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woo SL, Hollis JM, Adams DJ, Lyon RM, Takai S. Tensile properties of the human femur-anterior cruciate ligament-tibia complex. The effects of specimen age and orientation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wren TA, Lindsey DP, Beaupre GS, Carter DR. Effects of creep and cyclic loading on the mechanical properties and failure of human Achilles tendons. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31(6):710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yahia L, Brunet J, Labelle S, Rivard CH. A scanning electron microscopic study of rabbit ligaments under strain. Matrix. 1990;10(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zantop T, Herbort M, Raschke MJ, Fu FH, Petersen W. The role of the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles of the anterior cruciate ligament in anterior tibial translation and internal rotation. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.