Abstract

The apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) is the strongest genetic risk factor or developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Our recent identification of altered APOE DNA methylation in AD postmortem brain (PMB) prompted this follow-up study. Our goals were to (i) validate the AD-differential methylation of APOE in an independent PMB study cohort and (ii) determine the cellular populations (i.e., neuronal vs. non-neuronal) of AD PMB that contribute to this differential methylation. Here, we obtained an independent cohort of 57 PMB (42 AD and 15 controls) and quantified their APOE methylation levels from frontal lobe and cerebellar tissue. We also applied fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) to separate neuronal nuclei from non-neuronal nuclei within the tissue of 15 AD and 14 control subjects. Bisulfite pyrosequencing was used to generate DNA methylation profiles of APOE from both bulk PMB and FANS nuclei. Our results provide independent validation that the APOE CGI holds lower DNA methylation levels in AD compared to control in frontal lobe but not cerebellar tissue. Our data also indicate that the non-neuronal cells of the AD brain, which are mainly composed of glia, are the main contributor to the lower APOE DNA methylation observed in AD PMB. Given that astrocytes are the primary producers of apoE in the brain our results suggest that alteration of epigenetically regulated APOE expression in glia could be an important part of APOE’s strong effect on AD risk.

Keywords: Apolipoprotein E (APOE), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), DNA methylation, epigenetics, fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS), glia

1. Introduction

The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) is a well-established genetic risk factor for the late-onset form of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). There are three genetic variants of the human APOE gene, ε2, ε3, and ε4. The presence of one ε4 allele increases a person’s risk of developing AD by 2- to 3-fold and the presence of two ε4 alleles increases the risk by about 12-fold compared to individuals without any ε4 alleles (Liu et al., 2013). Each allele defines a unique amino acid sequence of the apoE protein, thus in the past, research into APOE in AD risk has mainly focused on apoE isoform-specific differences in the protein’s structure and functions. However, knowledge gaps still exist with such protein-oriented studies, and the molecular mechanisms through which the ε4 allele contributes to an increased risk of AD remain incompletely understood. Individuals who inherit the ε4 allele produce apoE4 throughout their lifespan, yet a large portion of ε4 carriers never develop AD (Liddell et al., 2001). Thus, it is likely that additional ε4-allele associated genetic, epigenetic, and/or environmental components contribute to the complex non-Mendelian disease etiology observed in AD.

APOE has a distinct epigenetic signature in that its last exon contains a high number of cytosine phosphate guanine (CpG) dinucleotides. This region constitutes APOE’s one and only CpG island (CGI). CGIs located near the 3’-end of genes, such as the APOE CGI (Supplemental Figure 1), are rare in the human genome and represent <1% of all CGI’s (Maunakea et al., 2010). Notably, the two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that define the ε2/ε3/ε4 alleles of APOE are both CpG dinucleotide altering, such that the ε4 allele introduces an additional CpG site in an already CpG-dense region (i.e., four CpGs within 12 bp) compared to the ε3 and ε2 alleles. In contrast, the ε2 allele eliminates one CpG site to open up a 33-bp CpG-free region compared to the ε3 and ε4 alleles (Yu and Foraker, 2015). Whether such a difference in the epigenetic code can lead to diverse epigenetic changes and contributes to the differential AD risks associated with the ε2/ε3/ε4 alleles is currently under investigation.

Recently, we showed that the APOE CGI is differentially methylated in the postmortem brain (PMB) of AD subjects compared to control subjects in a tissue- and APOE-genotype-specific manner. These differences are enriched in two differentially methylated regions (DMRs) depicted in Supplemental Figure 1. DNA methylation in these regions was reduced by an average of 7% in AD compared to controls (Foraker et al., 2015). However, our previous study was limited to analysis of bulk brain tissue and reflects the DNA methylation patterns of mixed cellular populations within the PMB. The major cell types of the human brain include neurons and glial cells (i.e., astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia), all of which are known to play a distinct role in AD-pathogenesis (Dzamba et al., 2016). Furthermore, epigenomes are known to differ between cell types (Davies et al., 2012; Iwamoto et al., 2011; Kozlenkov et al., 2014) with neurons holding higher global levels of DNA methylation than glial cells (Coppieters et al., 2014). It is possible that methylation differences between AD and control brain have cell type specificity, which may provide insight into AD pathophysiology at the cellular level. Thus, we designed the current study to further explore the epigenetic characteristics of one of our previously identified APOE DMRs in PMB. First, we validated a previously characterized DMR in an independent cohort of AD and control subjects. Secondly, we separated neurons and glia using fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) to determine the cellular source behind the AD DMR.

2. Results

2.1. AD-specific APOE DMR in the Validation Cohort

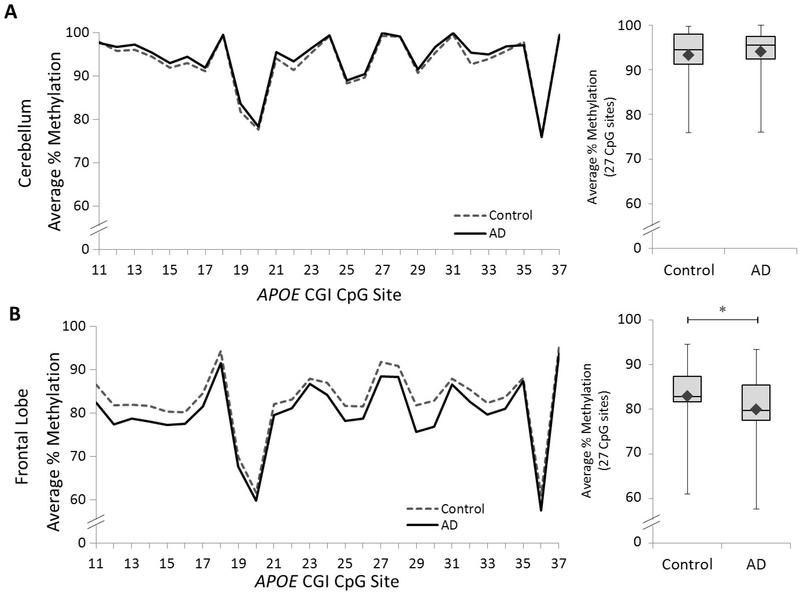

To validate our previously discovered APOE DMR (i.e., CpG# 11–37)(Foraker et al., 2015), we quantified DNA methylation levels across this region in postmortem frontal lobe and cerebellar samples from an independent validation cohort of 57 subjects (15 control, 42 AD; see Table 1). As in our previous study, we found no significant difference in cerebellar APOE between groups (Figure 1A and Supplemental Table 1). However, in the frontal lobe, we observed a statistically significant decrease in methylation in the AD group compared to controls (Figure 1B and Supplemental Table 2). These results provide independent validation that a 5’-portion of the APOE CGI, which we previously defined as DMR I, holds lower DNA methylation levels in AD compared to control in frontal lobe tissue.

Table 1.

Subject and tissue demographics

| Validation Cohort* | Total | AD | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample number - n | 57 | 42 | 15 |

| Age at death – mean (SD) | 87.8 (6.9) | 88.0 (6.1) | 87.2 (9.1) |

| Postmortem interval (h) – mean (SD) | 5:17 (2:26) | 5:08 (2:31) | 5:21 (2:17) |

| Gender – n male (% male) | 22 (39%) | 15 (36%) | 7 (47%) |

| Braak stage – mean (SD) | 4.5 (1.9) | 5.6 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| APOE | |||

| ε3/ε3 – n (%) | 29 (51%) | 15 (36%) | 14 (93%) |

| ε3/ε4 – n (%) | 16 (28%) | 15 (36%) | 1 (7%) |

| ε4/ε4 – n (%) | 12 (21%) | 12 (29%) | 0 (0%) |

| FANS Cohort | Total | AD | Control |

| Sample number - n | 29 | 15 | 14 |

| Age at death – mean (SD) | 84.3 (8.0) | 84.0 (7.3) | 84.7 (9.1) |

| Postmortem interval (h) – mean (SD) | 5:15 (2:11) | 5:45 (2:30) | 4:42 (1:41) |

| Gender - n male (% male) | 18 (62%) | 12 (80%) | 6 (50%) |

| Braak stage – mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.8) | 5.6 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.8) |

| APOE | |||

| ε3/ε3 – n (%) | 12 (41%) | 5 (33%) | 7 (50%) |

| ε3/ε4 – n (%) | 12 (41%) | 5 (33%) | 7 (50%) |

| ε4/ε4 – n (%) | 5 (17%) | 5 (33%) | 0 (0%) |

Cerebellum tissue was not available for one of the AD subjects

Figure 1. DNA methylation profiles of the APOE CGI in the validation cohort.

Left panel: graphs depict the average percentage of DNA methylation for 42 AD and 15 control subjects from (A) cerebellar and (B) frontal lobe tissue at each of 27 CpG sites from the APOE CGI (2 AD subjects are missing cerebellar data). Right panel: box and whisker plot depicts the range (upper and lower bars) and mean (denoted by ♦) of DNA methylation average percentages across the same 27 CpG sites. The following p-values, point estimates, and 95% confidence intervals represent the effect of disease status (Control – AD) on percent methylation and are based on a linear mixed effects model: Cerebellum: p = 0.81, −0.3 [–2.5, 2.0]; Frontal lobe: ∗p = 0.01, 2.9 [0.7, 5.2].

We further examined the effect of APOE genotype on methylation. No significant difference was detected between AD and controls with the ε3/ε3 genotype, but a statistically significant reduction in APOE methylation was found in AD patients with ε3/ε4 genotype compared to controls. These results are consistent with our previous findings (Foraker et al., 2015). When data from our current study and previous study were combined together, the methylation patterns of each group remained the same (Supplemental Figure 2). Overall, this result suggests that the divergent DNA methylation levels observed between the AD and control groups are mainly owed to the APOE ε3/ε4 heterozygous subjects.

2.2. Separation of neuronal and glial cell populations from frontal lobe PMB

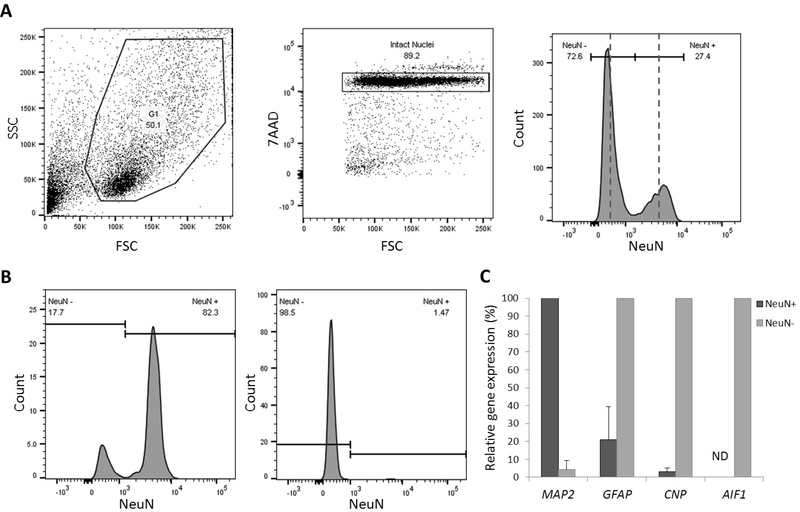

In order to determine which cell population(s) contributed to this altered DNA methylation in AD brain, we established a FANS procedure to separate neuronal nuclei from non-neuronal nuclei. Given that the non-neuronal cellular population in the brain is composed primarily of astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes with only small amounts of vascular cells and nucleated bloods cells, we use the general term “glia” to refer to this non-neuronal cell population. We used an anti-NeuN antibody to label neuronal nuclei in bulk frontal lobe nuclei preparations and subsequently isolated the labeled and unlabeled nuclei (Figure 2A). We applied this FANS procedure to separate neuronal and glial nuclei from a subset (15 AD and 14 control PMBs) of our available samples (Table 1, FANS cohort). Using this method, we were able to generate DNA methylation profiles from both NeuN+ (neuronal) nuclei and NeuN− (glial) nuclei.

Figure 2. FANS of neuronal and glial nuclei from PMB.

Nuclei were isolated from frozen postmortem frontal lobe tissue and were stained with the DNA marker 7AAD and an antibody targeting NeuN. (A) Left panel: Dot plot for side-scatter (y-axis) and forward-scatter (x-axis). Middle panel: Dot plot for 7AAD, single intact nuclei were selected for gating. Right panel: Histogram showing separate peaks for NeuN− and NeuN+ nuclei. Representative sort gates are depicted by dashed lines (left of the first line was sorted as NeuN−; right of the second line was sorted as NeuN+). (B) Left panel: Representative histogram of NeuN expression in NeuN+, neuronal nuclei. Right panel: Representative histogram of NeuN expression in NeuN−, glial nuclei. (C) Bar graph of relative gene expression of four phenotypic markers in NeuN+ (neuronal) and NeuN− (glial) sorted nuclei. Three different subjects were used for each sort (n =3), error bars represent standard deviation. G1 = gate 1; ND = not detected.

To confirm the sort purity of the obtained neuronal and glial populations we re-ran a small aliquot of the sorted nuclei through the flow cytometer and measured the percentage of NeuN positivity (Figure 2B). Using this follow-up procedure, we observed a mean sort purity of 83.2% ± 15.8 (mean ± SD) in NeuN+ and 97.6% ± 2.7 (mean ± SD) in NeuN− (Figure 2B). To further validate sort quality, we used qRT-PCR to measure mRNA expression levels of cell type-specific gene markers (Figure 2C). Although this setting is limited to quantifying the pre-translation mRNA contained in the nucleus, single nuclei studies have shown that expression of nuclear RNA transcripts is highly similar to whole-cell RNA preparations in neurons (Grindberg et al., 2013). As expected, NeuN+ nuclei showed full expression of the neuronal marker MAP2, but very low or no expression of the astrocytic marker GFAP, the oligodendroglial marker CNP, and microglial marker AIF1, whereas the opposite pattern was true for the NeuN− nuclei. Together, these results confirm that our FANS procedure sufficiently separates neuronal and glia nuclei from postmortem brain tissues.

2.3. Neuronal vs. glial ratios in frontal lobe PMB

Given that neuronal-loss is a hallmark of AD pathology we entertained the possibility that an AD-related shift in the neuron to glia ratio is behind the observed difference in the APOE CGI methylation levels. To determine if neuronal loss is associated with the differential methylation levels in frontal lobe tissue, we analyzed flow cytometry data to determine ratios of neuronal to total cell nuclei. These ratios were highly variable across individual samples but were not significantly different between AD and control groups (Supplemental Figure 3). The average percentage of NeuN+ nuclei in total nuclei was 24.8% ± 12 (mean ± SD) in AD compared to 22.0% ± 12.5 (mean ± SD) in the control group. This data suggests that the reduced methylation we observed with AD in the APOE CGI cannot be attributed to shifting densities of neuronal and/or glial populations.

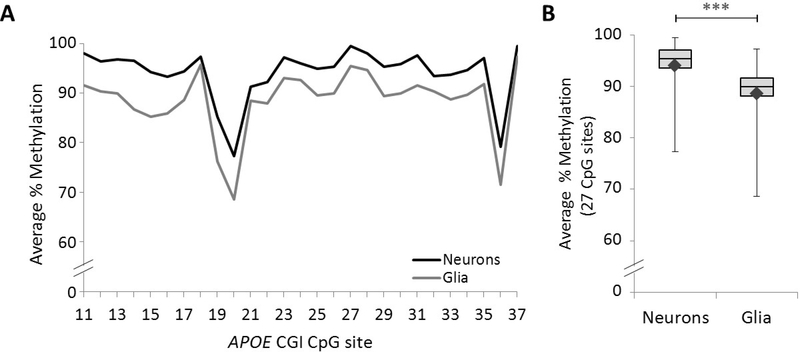

2.4. Cell type-specific methylation profiles of the APOE CGI

To determine the cell-specific methylation profiles of the APOE CGI in frontal lobe PMB we quantified DNA methylation levels in neuronal and glial DNA from all 29 study samples in the FANS cohort. Pyrosequencing data from one of the NeuN− nuclear DNA samples did not meet quality control standards thus we were only able to obtain glial data for 28 of the samples. Overall, we observed the neuronal APOE gene carries a significantly higher level of DNA methylation compared to the glial APOE (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 3. APOE CGI methylation in frontal lobe neuronal and glial nuclei.

(A) Graph depicts the average percentage of DNA methylation for 29 neuronal and 28 glial preparations at each of the 27 CpG sites across part of the APOE CGI. (B) Box and whisker plot depicts the range (upper and lower bars) and mean (denoted by ♦) of DNA methylation average percentages from the same 27 CpG sites (Neurons – Glia: ***p < 0.001, 5.1, 95% CI [4.2, 6.1] based on a linear mixed effect model).

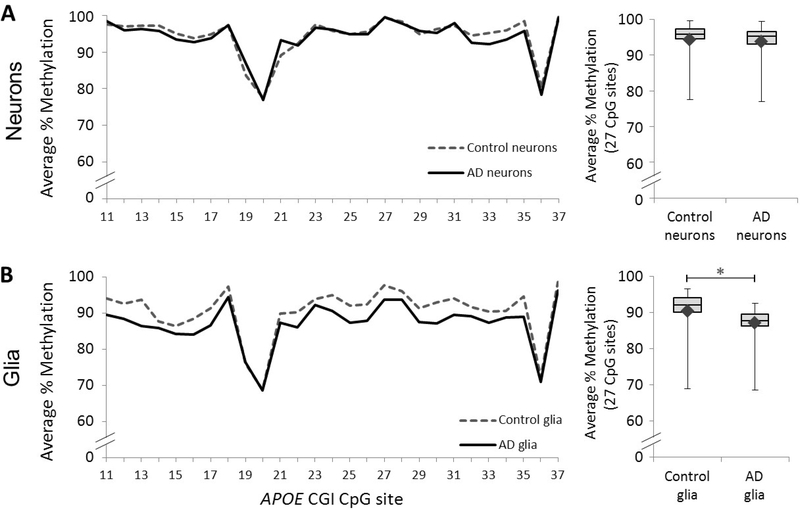

We further compared methylation profiles of AD vs control in neuronal, glial and unsorted DNA. No significant methylation differences were observed in the neuronal DNA (Figure 4A and Supplemental Table 4); however, there was a significant APOE methylation reduction in AD glial DNA compared to control (Figure 4B and Supplemental Table 5). As expected, we saw reduced methylation levels in the unsorted AD nuclei compared to controls; however this difference was not statistically significant (Supplemental Figure 4). This data suggests that the observed methylation reduction in the AD APOE CGI is glia-specific.

Figure 4. APOE CGI methylation profiles of neuronal and glial PMB cells.

Left panel: Graph depicts the average percentage of DNA methylation for Control and AD subjects at each of 27 CpG sites across the APOE CGI in (A) neuronal and (B) glial nuclei. Right panel: Box and whisker plot depicts the range (upper and lower bars) and mean (denoted by ♦) of DNA methylation average percentages across the same 27 CpG sites in (A) neuronal and (B) glial nuclei. The following p-values, point estimates, and 95% confidence intervals represent the effect of disease status (Control – AD) on percent methylation and are based on a linear mixed effects model: Neurons: p = 0.56, 1.0 [–2.4, 4.3]; Glia: ∗p = 0.04, 3.5 [0.1, 6.9].

3. Discussion

This study shows that an APOE related methylation change in AD is reproducible in an independent cohort and, for the first time, demonstrates that this epigenetic alteration mainly occurs in glial cells.

3.1. Epigenetics in AD

It is possible that environment and lifestyle can modify AD risk through epigenetic mechanisms (Coppede and Migliore, 2010; Nicolia et al., 2015); therefore, identifying epigenetic markers of AD is a worthwhile research topic. While a number of studies have focused on global DNA methylation changes in AD, the results remain inconsistent and a general pattern has yet to be agreed upon (Wen et al., 2016). However, a few specific genes with consistent aberrant methylation in the AD brain have been identified. These include, BDNF (Chang et al., 2014; Nagata et al., 2015) and SORBS3 (Sanchez-Mut et al., 2013; Siegmund et al., 2007). In this study, we show that the AD-specific DMR of APOE can be reliably detected in AD-impacted brain tissue. Whether this epigenetic alteration is a cause or a consequence of AD is currently unknown and warrants further studies. Additionally, it is possible that other APOE related diseases share this epigenetic aberration. Thus, generating APOE methylation profiles from other neurodegenerative disease will be necessary to assess the AD-specificity of this epigenetic mark.

3.2. Cellular and biological implications

Epigenetics lies at the intersection of environment and genetics and may provide the key to understanding complex diseases such as AD. In this study, we observed that the glial fraction of PMB, which is mainly composed of astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia, held the largest AD-specific decrease in APOE CGI methylation. This is not surprising, given that astrocytes and microglia are the main apoE producers in the brain and that neurons do not express APOE under normal conditions (Liu et al., 2013). Altered DNA methylation levels at gene promotor CGIs are known to change gene expression patterns. However, the APOE CGI is not a canonical promoter 5’-CGI and, currently, functions of such 3’-CGIs are largely unknown. Nevertheless, it may be possible that the APOE CGI’s altered methylation levels could affect gene transcription of APOE through less classical mechanisms such as alternative promoters (Maunakea et al., 2010) or through altering elongation efficiency of mRNA (Lorincz et al., 2004). Here, the observation of a greater range of DNA methylation changes in glia suggest that methylation levels of the APOE CGI may impact APOE expression. Unfortunately, the APOE expression levels in brain cell nuclei we examined were too low to determine if such a correlation exists. Suggesting, that in depth analysis of APOE transcript levels may be beyond the limitations of the FANS method used in this study. Since the majority of mRNA transcripts are cytoplasmic, a whole-cell approach in neurons and glia may be necessary to fully understand the role, if any, APOE CGI methylation plays in APOE transcription.

Beyond the APOE gene, we can further speculate that the loss of APOE methylation in some glial cells could have additional aberrant biological effects. For example, complete loss of methylation in this region could potentially have altered regulatory effects on other cis- or trans-genes (Aran et al., 2013) potentially affecting the glial cells supporting functions and even contributing to AD risk or pathophysiology. Of course, this is just one possibility and more glia specific APOE gene-regulatory studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

It will be interesting to further separate the glial nuclei into sub-populations, including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendroglia, in future studies. This is challenging given that such a method is limited to immunolabeling of phenotypic markers, which must be expressed in the nucleus. Nevertheless, an oligodendroglial-specific protein, Olig2, (Okada et al., 2011) could provide a point of entry to probe into oligodendrocytes for their methylation profiles.

The cell specific methylation profiles observed here are consistent with those observed by Coppieters et al. who showed that neurons have higher overall methylation levels compared to glia (Coppieters et al., 2014). These results are also in line with our previous observation of higher APOE methylation levels in the cerebellum (Yu et al., 2013), which has a higher neuron to glia ratio compared to frontal lobe tissue (Azevedo et al., 2009). Decreased DNA methylation levels were observed in AD glia but not AD neurons, suggesting the involvement of the passive demethylation mechanism (Wu and Zhang, 2010), given that neurons are post-mitotic yet glia are not. Of further interest, we found the overall methylation pattern of this region to be similar across all cell types. Thus, while the overall levels of methylation were decrease in AD glia, the relative distribution of methylation within the APOE CGI remained consistent.

3.3. Considerations and future directions

Our FANS data showed that the ratios of neuronal to total-cell nuclei were not different between AD and control frontal cortex. This result could be evidence of neuronal shrinkage as opposed to neuronal loss in AD. Alternatively, since our method only quantifies the ratio of neurons to glia, it may be that both cell types have been reduced equally in the AD tissues we studied. Thus, no shift in ratio would be observed. Finally, although this flow cytometric method provides useful information regarding the cellular composition of the tissue, it was not designed for accurate cell type quantification and we have not properly assessed the technical variability of this method. Thus, further studies are needed to fully corroborate this finding.

One constraint of this study was the limited number of controls in the validation cohort. As in our previous study, we were unable to find any age-matched control subjects with the ε4/ε4 homozygous APOE genotype and were thus unable to examine methylation differences between AD and controls with this genetic background. Also, in our previous study, of the 10 control subjects, half had the ε3/ε4 APOE genotype and half had the ε3/ε3 APOE genotype, whereas in the current study, of the 15 control subjects, only one had the ε3/ε4 APOE genotype and the other 14 had the ε3/ε3 APOE genotype. This may explain why in our current study the estimated difference in percent methylation between AD and control subjects in the DMR is smaller than in our previous study (2.9, 95% CI [0.7, 5.2] versus 6.0, 95% CI [2.9, 9.2]). The lack of ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4 genotype control subjects in our validation cohort is due, in part, to the low incidence of people meeting these criteria in the general population. Furthermore, we were limited to the availability of tissue in our neuropathology core. Despite this limitation we were able to see a statistically significant reduction in APOE methylation of ε3/ε4 AD patients compared to ε3/ε4 controls. Furthermore, analysis on combined data from our previous cohort (Foraker et al., 2015) and the validation cohort, from this study, showed a similar reduction of APOE methylation in heterozygous ε3/ε4 AD patients with an even lower p-value. This validates our previous study, in which we showed the greatest loss of APOE methylation in frontal lobe PMB between AD and control subjects was for subjects with the ε3/ε4 APOE genotype. Furthermore, this result suggests that the ε4 allele may be associated with local DNA methylation changes in the AD brain since no differences were found between homozygous ε3/ε3 AD subjects compared to controls. However, we advise that these results be interpreted with caution and that future studies with larger sample size include a balanced number of ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4 controls in order to fully assess the effects of APOE genotype on APOE CGI methylation in AD glial cells.

3.4. Conclusions

Overall, this work suggests that methylation of the APOE gene in glial cells is reduced in the AD brain compared to age-matched controls. Given that astrocytes are the primary producers of apoE in the brain, this finding together with previous observations of APOE gene methylation loss, might be an important lead into understanding the neuropathological mechanism underlying the strong association of the APOE ε4 allele with AD risk. Furthermore, the role of DNA methylation as an intersection for gene-environment interactions further highlights methylation of this APOE CGI as a strong candidate for additional epigenetic study into the etiology and pathophysiology of this complex and devastating disease.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Postmortem human brain tissue

The use of human tissues in this study was approved by the human subject Institutional Review Board of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. Autopsy materials used in this study were obtained from the University of Washington Neuropathology Core, which is supported by the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (AG05136), the Adult Changes in Thought Study (AG006781), and the Morris K Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research (NS062684). Tissue from the middle frontal gyrus was obtained, rapidly frozen at autopsy (≤ 11 hrs after death) and stored at −80°C until use. Patient diagnosis was confirmed postmortem by neuropathological analysis. Brains from AD patients exhibited Braak stages between V-VI, whereas control subjects ranged between stages I-III with the exception of one control sample whose Braak stage could not be evaluated due to the condition of the tissue.

For the validation cohort, postmortem frontal lobe from the middle frontal gyrus and cerebellar tissues from an independent cohort of control and AD subjects were selected. Due to limited availability of PMB tissue, the FANS cohort was comprised of frontal lobe tissue from the 15 AD and 10 control subjects from our previous study (Foraker et al., 2015) as well as from 4 control subjects in the validation cohort.

4.2. Nuclei isolation and separation

Nuclei isolation and separation was performed according to previously established methods (Iwamoto et al., 2011; Matevossian and Akbarian, 2008; Okada et al., 2011) with minor modifications. Briefly, 250 mg of frozen frontal lobe PMB tissue was homogenized in 5 mL of lysis buffer (0.32 M Sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCL pH 8, 5 mM CaCl2, 3 mM Mg(Acetate)2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton x-100). Homogenates were transferred to a 15 mL ultracentrifuge tube and 9 mL of Sucrose Solution (1.8 M Sucrose, 3 mM Mg(Acetate)2, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM Tris-HCL pH 8) was added to the bottom of the tube prior to ultracentrifugation (Beckman, L8–80M, SW28 rotor) at 27,000 rpm for 2.5 hrs at 4°C. After removal of the supernatant and debris, the nuclei pellet was gently dissolved in 500 μL of cold PBS and incubated on ice for 20 min and the integrity of the nuclei was checked by light microscopy. Neuronal nuclei were labeled using an anti-NeuN mouse monoclonal antibody (1:500, Millipore, #MAB377) targeting a neuronal nuclear antigen and an alexa-488 anti-mouse IgG Zenon Kit (Molecular probes Z-25002). In one sample, primary antibody was omitted to control for non-specific binding of the secondary antibody. All nuclei were stained with 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) DNA dye (1:1,000, Sigma).

NeuN+ (neuronal) and NeuN− (glial) nuclei were sorted based on standard gating procedures using a FACSAria III sorter with aerosol management (BD Biosciences) in accordance with BSL-2 procedures at the UW Pathology Flow Cytometry Core Facility. Data was collected with FACSDiva 6.0 software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by FlowJo (FlowJo, LLC). A portion of the sorted neuronal and glial nuclei were reanalyzed by flow cytometry to confirm sort purity. For each sample, approximately 500,000 neuronal and 500,000 non-neuronal nuclei were sorted into separate tubes containing 200 μL of sucrose solution for a final volume of 1.5 mL. To maintain nuclear integrity 6 μL of 1 M CaCl2 and 3.66 μL of 1 M Mg(Acetate)2 was added to each tube (Jiang et al., 2008). Finally, the sorted and unsorted nuclear fractions were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C until DNA isolation.

4.3. DNA/RNA isolation

Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen nuclear pellets using PicoPure DNA isolation kits (ThermoFisher, cat# KIT0103) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μL of Extraction Solution was added to each pellet and incubated at 65°C for 3 hrs. Samples were incubated at 95°C for 10 min to deactivate Proteinase K and DNA was purified by ethanol precipitation. Nuclear RNA was isolated using PicoPure RNA isolation kits (ThermoFisher, cat# KIT0204). Up to 160,000 nuclei were sorted directly into extraction buffer, incubated at 42°C for 30 minutes, and centrifugation at 3,000 x g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C prior to RNA Isolation. RNA isolation was completed as per the manufacturer’s instructions and nucleic acid concentrations were measured by NanoPhotometer (Implen).

4.4. Bisulfite pyrosequencing

Quantification of DNA methylation levels by pyrosequencing was performed as previously reported (Foraker et al., 2015). Briefly, genomic DNA (500 ng each) was bisulfite converted using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen). To evaluate the methylation status of the APOE CGI, we used a pyrosequencing assay designed to cover the 27 CpG sites of the previously identified DMR (DMR I), starting with the 11th CpG of the APOE CGI and ending with the 37th CpG (chr19: 45411858 – 45412063; hg19). Specific genomic coordinates for each CpG site are given in Supplemental Table 6. It is important to note that rs429358 (chr19: 45411941; hg19), is located between CpG#21 and #22. This SNP separates the ε4 from the ε2/ε3 alleles, and is not a CpG site on the reference sequence of the ε3 allele. Although we obtained methylation data on this site, since this is not a CpG site in ε3 carriers this data is not presented. Two PCR primers and 6 sequencing primers (Supplemental Table 7a) were designed using PyroMark Assay Design software version 2.0 (Qiagen). PCR was performed on approximately 20 ng of bisulfite-converted DNA using PyroMark PCR kits (Qiagen) on a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Specific amplification of the PCR product was checked by capillary electrophoresis on a QIAxcel system (Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplemental Figure 5). Pyrosequencing was carried out on a PyroMark Q24 system (Qiagen) and data was analyzed using PyroMark Q24 software, version 2.0.6 (Qiagen). Bisulfite treatment controls were integrated as a quality control measure.

4.5. Real time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

To quantify cell type-specific gene expression, we performed standard qRT-PCR. Briefly, nuclear RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) with random primers. RNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers and a 7900 ABI real-time instrument (Applied Biosystems). SYBR Green SuperMix was used for all cell-specific gene targets and a TaqMan gene expression assay kit for human actin beta (ACTB) was used as an internal control (ThermoFisher, Assay # Hs99999903_m1). All samples were performed in duplicate and cycle numbers were averaged. Primer sequences (Supplemental Table 7b) were obtained from previously published work including allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF1) (Lorente-Cebrian et al., 2013), 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNP) (Croitoru-Lamoury et al., 2011), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Yang et al., 2015). Microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) primers were designed in-house using Primer 3 online software (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method with ACTB as a reference gene.

4.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 13 (SPSS). For the validation cohort, we measured the percentage of methylated cytosines at each of the 27 CpG sites from the APOE CGI in the frontal lobe and cerebellum of each subject. To compare overall percentages by disease status (AD vs. control) we used a linear mixed effects model to account for repeated measures on a subject across CpG sites and tissue types. This model included fixed effects for disease status and tissue type, as well as a second-order interaction to allow for the effects of disease status to vary by tissue type.

To compare methylation levels by APOE genotype and disease status we used a second linear mixed effects mode, accounting for repeated measures on a subject and across CpG sites and tissue sites. This model included fixed effects for disease status, APOE genotype, and tissue type as well as all second-order interactions involving tissue (to allow for the effects of disease status and APOE genotype to vary by tissue type), as well as the second-order interaction term for disease status by APOE genotype and a three-way interaction term for disease status by APOE genotype by tissue type (to allow the effect of disease status to vary by both APOE genotype and tissue type). An identical mixed linear effects model was then run on the validation cohort data combined with methylation data from frontal lobe and cerebellar tissue of 15 AD and 10 control subjects from our previous study (Foraker et al., 2015).

For the FANS cohort, we measured the percentage of methylated cytosines at each of the same 27 CpG sites in neuronal and glial nuclei from frontal lobe tissue for each subject. We used a linear mixed effects model to account for repeated measures on a subject across CpG sites and sort group (neuronal vs. glial). In our first model, we compared overall percentages by sort group, ignoring disease status (AD vs. control), by including a fixed effect for sort group. In our second model, we compared overall percentages by disease status by including fixed effects for disease status and sort group, as well as a second-order interaction to allow for the effects of disease status to vary by sort group. As a supplemental analysis, we compared overall percentages by disease status using all available nuclei (denoted here as “unsorted”).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research Program and the University of Washington Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) Pilot Project Award.

Abbreviations:

- 7AAD

7-Aminoactinomycin D

- ACTB

actin beta

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AIF1

allograft inflammatory factor 1

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- CGI

CpG island

- CNP

2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase

- CpG

cytosine phosphate guanine

- DMR

differentially methylated region

- FANS

fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MAP2

Microtubule-associated protein 2

- ND

not detected

- NS

not significant

- NeuN

neuronal nuclear antigen

- PMB

postmortem brain

- qRT-PCR

real time quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

References

- Aran D, Sabato S, Hellman A, 2013. DNA methylation of distal regulatory sites characterizes dysregulation of cancer genes. Genome Biol. 14, R21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo FA, Carvalho LR, Grinberg LT, Farfel JM, Ferretti RE, Leite RE, Jacob Filho W, Lent R, Herculano-Houzel S, 2009. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 513, 532–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Wang Y, Ji H, Dai D, Xu X, Jiang D, Hong Q, Ye H, Zhang X, Zhou X, Liu Y, Li J, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhou D, Zhuo R, Zhang Y, Yin H, Mao C, Duan S, Wang Q, 2014. Elevation of peripheral BDNF promoter methylation links to the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 9, e110773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppede F, Migliore L, 2010. Evidence linking genetics, environment, and epigenetics to impaired DNA repair in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 20, 953–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters N, Dieriks BV, Lill C, Faull RL, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, 2014. Global changes in DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in Alzheimer’s disease human brain. Neurobiol Aging. 35, 1334–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru-Lamoury J, Lamoury FM, Caristo M, Suzuki K, Walker D, Takikawa O, Taylor R, Brew BJ, 2011. Interferon-gamma regulates the proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via activation of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO). PLoS One. 6, e14698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, Lunnon K, Dixit A, Lovestone S, Coarfa C, Harris RA, Milosavljevic A, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Dobson R, Schalkwyk LC, Mill J, 2012. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biol. 13, R43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzamba D, Harantova L, Butenko O, Anderova M, 2016. Glial Cells - The Key Elements of Alzheimer s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 13, 894–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraker J, Millard SP, Leong L, Thomson Z, Chen S, Keene CD, Bekris LM, Yu CE, 2015. The APOE Gene is Differentially Methylated in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 48, 745–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindberg RV, Yee-Greenbaum JL, McConnell MJ, Novotny M, O’Shaughnessy AL, Lambert GM, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Lee J, Fishman M, Robbins GE, Lin X, Venepally P, Badger JH, Galbraith DW, Gage FH, Lasken RS, 2013. RNA-sequencing from single nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110, 19802–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Ueda J, Oldham MC, Ukai W, Hashimoto E, Saito T, Geschwind DH, Kato T, 2011. Neurons show distinctive DNA methylation profile and higher interindividual variations compared with non-neurons. Genome Res. 21, 688–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Matevossian A, Huang HS, Straubhaar J, Akbarian S, 2008. Isolation of neuronal chromatin from brain tissue. BMC Neurosci. 9, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlenkov A, Roussos P, Timashpolsky A, Barbu M, Rudchenko S, Bibikova M, Klotzle B, Byne W, Lyddon R, Di Narzo AF, Hurd YL, Koonin EV, Dracheva S, 2014. Differences in DNA methylation between human neuronal and glial cells are concentrated in enhancers and non-CpG sites. Nucleic Acids Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell MB, Lovestone S, Owen MJ, 2001. Genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease: advising relatives. Br J Psychiatry. 178, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G, 2013. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 9, 106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente-Cebrian S, Decaunes P, Dungner E, Bouloumie A, Arner P, Dahlman I, 2013. Allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF-1) is a new human adipokine involved in adipose inflammation in obese women. BMC Endocr Disord. 13, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorincz MC, Dickerson DR, Schmitt M, Groudine M, 2004. Intragenic DNA methylation alters chromatin structure and elongation efficiency in mammalian cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11, 1068–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matevossian A, Akbarian S, 2008. Neuronal nuclei isolation from human postmortem brain tissue. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunakea AK, Nagarajan RP, Bilenky M, Ballinger TJ, D’Souza C, Fouse SD, Johnson BE, Hong C, Nielsen C, Zhao Y, Turecki G, Delaney A, Varhol R, Thiessen N, Shchors K, Heine VM, Rowitch DH, Xing X, Fiore C, Schillebeeckx M, Jones SJ, Haussler D, Marra MA, Hirst M, Wang T, Costello JF, 2010. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature. 466, 253–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Kobayashi N, Ishii J, Shinagawa S, Nakayama R, Shibata N, Kuerban B, Ohnuma T, Kondo K, Arai H, Yamada H, Nakayama K, 2015. Association between DNA Methylation of the BDNF Promoter Region and Clinical Presentation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 5, 64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolia V, Lucarelli M, Fuso A, 2015. Environment, epigenetics and neurodegeneration: Focus on nutrition in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 68, 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Saiwai H, Kumamaru H, Kubota K, Harada A, Yamaguchi M, Iwamoto Y, Ohkawa Y, 2011. Flow cytometric sorting of neuronal and glial nuclei from central nervous system tissue. J Cell Physiol. 226, 552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Mut JV, Aso E, Panayotis N, Lott I, Dierssen M, Rabano A, Urdinguio RG, Fernandez AF, Astudillo A, Martin-Subero JI, Balint B, Fraga MF, Gomez A, Gurnot C, Roux JC, Avila J, Hensch TK, Ferrer I, Esteller M, 2013. DNA methylation map of mouse and human brain identifies target genes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 136, 3018–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund KD, Connor CM, Campan M, Long TI, Weisenberger DJ, Biniszkiewicz D, Jaenisch R, Laird PW, Akbarian S, 2007. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS One. 2, e895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen KX, Milic J, El-Khodor B, Dhana K, Nano J, Pulido T, Kraja B, Zaciragic A, Bramer WM, Troup J, Chowdhury R, Ikram MA, Dehghan A, Muka T, Franco OH, 2016. The Role of DNA Methylation and Histone Modifications in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 11, e0167201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SC, Zhang Y, 2010. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11, 607–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Liu N, Tang Y, Hu Y, Zhang P, Pan C, Dong S, Zhang Y, Tang Z, 2015. Generation of neurospheres from human adipose-derived stem cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 743714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CE, Cudaback E, Foraker J, Thomson Z, Leong L, Lutz F, Gill JA, Saxton A, Kraemer B, Navas P, Keene CD, Montine T, Bekris LM, 2013. Epigenetic signature and enhancer activity of the human APOE gene. Hum Mol Genet. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CE, Foraker J, 2015. Epigenetic considerations of the APOE gene. Biomol Concepts. 6, 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.