Abstract

Patient: Male, 62

Final Diagnosis: Pituitary metastasis of small cell lung cancer

Symptoms: Blurred vision • weakness

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Pituitary gland metastasis is rarely the initial presentation of metastatic cancer. Most cases of pituitary gland metastasis are asymptomatic with diabetes insipidus being the most common symptomatic presentation. It can rarely present with symptoms of hormone underproduction such as secondary adrenal insufficiency. Although pituitary gland metastasis is rare, it is underestimated, as it is commonly misdiagnosed with pituitary gland adenoma due to the lack of clear radiological criteria differentiating between both.

Case Report:

We present a case of a 62-year-old male who presented with weakness, blurry vision, and persistent hypoglycemia despite intravenous dextrose infusion and having discontinued taking his diabetes medications. Chest x-ray showed a left hilar mass, while computed tomography scan demonstrated a left superior hilar mass and hilar lymphadenopathy with bilateral adrenal nodules and a T6 vertebral lesion suspicious for metastasis. Further workup showed secondary adrenal insufficiency with a low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level. Vertebral biopsy was performed and confirmed the diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of the lung. This was followed by a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed multiple metastatic lesions with an enhancing mass involving the right clivus, sella, and suprasellar cistern with mass effect on the optic chiasm and involvement of the cavernous sinus supporting the diagnosis of pituitary gland metastasis of small cell lung cancer. The patient received brain radiation, and repeated MRI showed regression of the previous MRI findings.

Conclusions:

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is an unusual presentation of pituitary gland metastasis. Physicians should take into consideration both radiological findings and presentation to differentiate between pituitary gland metastasis and pituitary adenoma.

MeSH Keywords: Neoplasm Metastasis, Pituitary Diseases, Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Background

Pituitary gland metastasis is very rare and represents only 1% of pituitary gland lesions [1–3]. It occurs most frequently in breast cancer and lung cancer [1,2,4]. Although small cell carcinoma of the lung commonly metastasizes to the brain, the pituitary gland is one of the least likely intracranial structures to be involved [1,4]. Metastasis to the pituitary gland is usually asymptomatic, as most patients die before having any related symptoms since it is usually associated with widespread malignancy at the time of diagnosis; however, the most common symptomatic presentation is diabetes insipidus [5–7]. Less often presentations include hypopituitarism, hyperprolactinemia, and optic chiasm compression symptoms including visual field defects, headaches, and diplopia [1,7–9]. Cases of pituitary metastasis presenting with symptoms of hormone insufficiency are rare. This is due to the lower predilection of malignancies to metastasize to the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Adrenal insufficiency is an uncommon complication of malignancy and mostly results from metastasis to the adrenal glands [10]. However, cases of secondary adrenal insufficiency due to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) under-production caused by metastasis to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis have been rarely reported in literature [10–17].

Pituitary gland metastasis is suspected to be underestimated, as it is commonly misdiagnosed as a pituitary adenoma [18] due to the lack of clear differentiating radiological findings. Current literature provides us with a few radiologic features that could help us differentiate pituitary metastasis from a pituitary adenoma. It is important for physicians to be familiar with these radiological findings, as management and prognosis of both entities are entirely different. Pituitary gland metastasis is rarely the first presentation of a malignancy [19]. Here we report a case of a 62-year-old male patient who was diagnosed with small cell carcinoma of the lung after presenting with hypoglycemia that was later found out to be due to ACTH underproduction resulting from pituitary gland metastasis. This case illustrates the unusual presentation of pituitary gland metastasis in the form of secondary adrenal insufficiency. Also, this case serves to aid physicians in differentiating between pituitary metastasis and pituitary adenoma by taking into consideration both nonspecific radiological findings and clinical presentation.

Case Report

A 62-year-old male with a history of tobacco abuse and diabetes mellitus, and who was taking metformin and glipizide, presented to the hospital for evaluation of unresponsiveness due to hypoglycemia. The patient had been feeling tired and weak for 1 week. Emergency medical services noted his glucose was 22 mg/dL, and on arrival to the Emergency Department, his glucose was still 37 mg/dL despite administration of intravenous glucose. The patient continued to remain persistently hypoglycemic despite continuous 10% dextrose infusion. Once the patient was more responsive, a review of systems also revealed a history of 5 weeks of blurry vision. Physical examination was notable for stage 2 clubbing and blurry vision without visual field deficits or diplopia.

Initially, the patient’s hypoglycemia was thought to be due to his poor oral intake with continued use of anti-glycemic medications and a possible interaction between his glipizide and Bactrim, which the patient was taking for a urinary tract infection for 3 days. However, his hypoglycemia was persistent for several days after stopping the medications, thus making drug interactions or sulfonylurea toxicity less likely. His morning cortisol level was checked during a hypoglycemic episode and was found to be low at 2.0 ug/dL (normal range: 6.0–18.4 ug/dL). Chest x ray revealed an opaque left hilar mass. Computed tomography chest characterized the left sided opacification as a superior hilar mass (Figure 1) with lymphadenopathy and showed another left sided nodule, bilateral adrenal nodules, and a T6 vertebral lytic lesion (Figure 2), all concerning for metastatic disease. The cosyntropin stimulation test showed an appropriate response to cosyntropin, ruling out primary adrenal insufficiency as the cause of hypoglycemia. Failure to achieve adequate cortisol response to severe hypoglycemia in the presence of normal adrenal responsiveness to cosyntropin favored ACTH deficiency in this patient, which was proven later by a low ACTH level. Given the concern for pituitary gland metastasis in the setting of his blurry vision and hypoglycemia due to ACTH deficiency, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained and demonstrated multiple (>10) supratentorial and infratentorial metastatic lesions, with an enhancing mass involving the right clivus, sella, and suprasellar cistern with mass effect on the optic chiasm in addition to involvement of the cavernous sinus. Further laboratory tests showed evidence of hypopituitarism with low follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (0.8 MIU/mL), luteinizing hormone (LH) (<0.1 MIU/mL) and total testosterone (<3ng/dL), but normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and mildly elevated prolactin (78 ng/mL) level, mostly consistent with pituitary stalk effect.

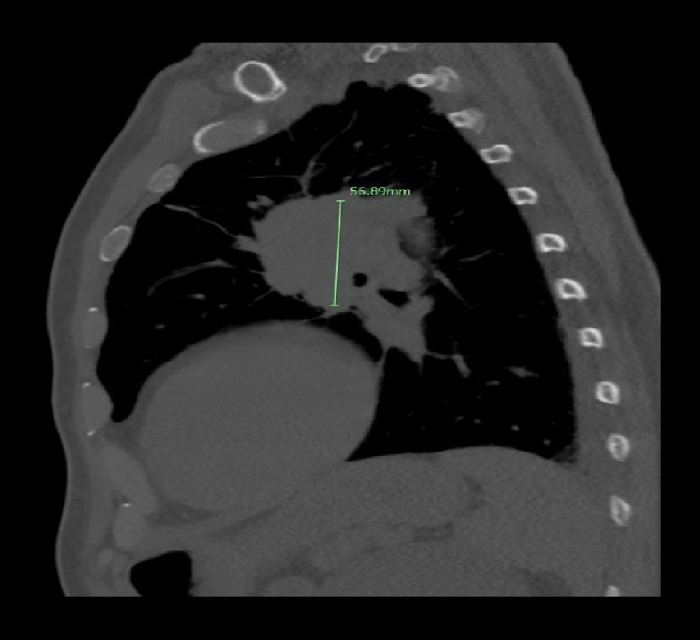

Figure 1.

Sagittal computed tomography scan of the chest demonstrating a 5.6 cm left superior hilar mass suspicious for pulmonary malignancy.

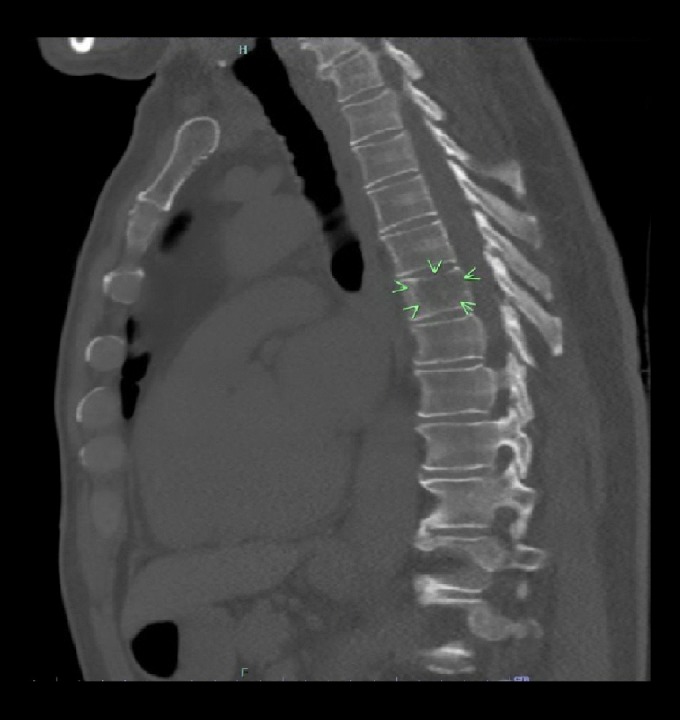

Figure 2.

Sagittal computed tomography scan of the chest showing the T6 vertebral lesion which was confirmed to be metastatic small cell lung cancer.

A vertebral biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of small cell lung cancer. Given the presence of multiple metastatic lesions and invasion of the cavernous sinus on brain MRI, we suspected that the suprasellar mass most likely represented pituitary metastatic lesions from small cell lung cancer. The patient was started on Decadron and underwent palliative brain radiation and chemotherapy. Brain MRI was repeated 3 months after treatment with radiation, and demonstrated significant regression of the large sellar/suprasellar enhancing mass with residual enhancement in the anterior sella and along the right lateral aspect of the sella (Figure 3).

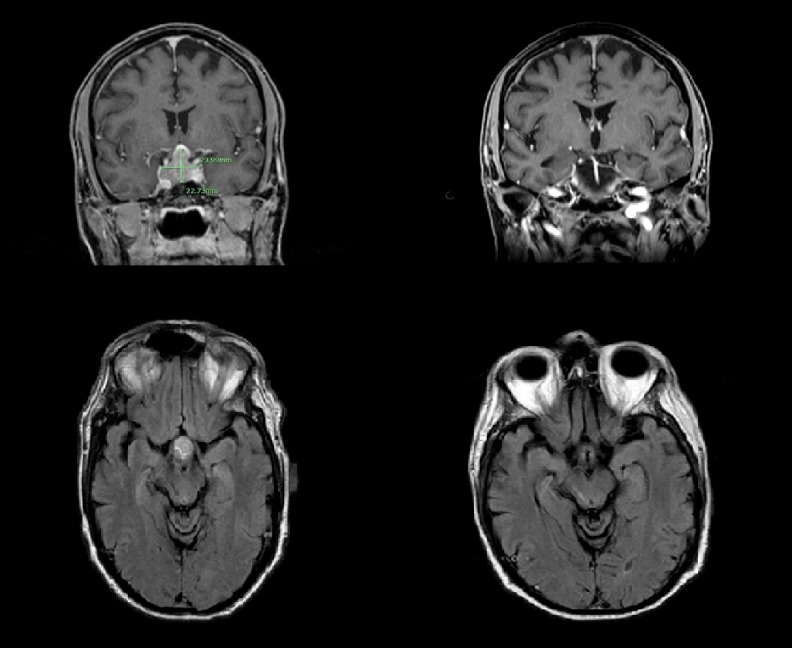

Figure 3.

Coronal (top) and axial (bottom) magnetic resonance imaging showing sellar/suprasellar pituitary mass (left) which appears to have regressed after 3 months of treatment with radiation, Decadron, and chemotherapy.

Discussion

Pituitary gland metastasis represents 1% of pituitary gland lesions. It has been detected in 5% of malignancies during autopsy; however, it was macroscopically evident only in two-thirds of these cases [1,20]. The majority of pituitary gland metastasis are asymptomatic, and most patients die before having any related symptoms due to wide spread malignancy at the time of diagnosis [1,4]. Very rarely, pituitary gland metastasis could be the first presentation of malignancy, as was the case in our patient [19]. Pituitary gland metastasis has been mostly reported in breast and lung cancer [1,2]. This could be due to it being the most common malignancies reported worldwide and by its tendency to metastasize to the brain. Another theory is that the pituitary gland is rich in prolactin receptors, which could induce the growth of metastatic cancerous breast cells in the pituitary gland by the chemotactic and proliferative effects of prolactin [1,8].

Only 7% of pituitary gland metastasis present with symptoms [1]. The most common symptomatic presentation for pituitary gland metastasis is diabetes insipidus [5–7], this could be explained by the predilection of malignancies to metastasize to the posterior pituitary gland and the infundibulum rather than the anterior pituitary gland [1]. McCormick et al., in their review of 40 symptomatic cases, noted diabetes insipidus in 70% of cases, reflecting posterior pituitary gland metastasis, whereas only 15% of cases had one or more anterior pituitary hormonal deficiencies, reflecting the involvement of the anterior pituitary gland [21]. The tendency to involve the posterior pituitary gland is explained by the anatomy and vascular supply of the gland as the posterior pituitary gland receives its blood supply directly from the systemic circulation, while the anterior pituitary gland receives its blood supply from the portal circulation via branches coming down the hypothalamus. Also, the posterior pituitary gland has a larger area of contact with the sella turcica, and this allows malignancies with high tendency for bone metastasis to metastasize to the pituitary gland via this route [1,7,9].

Patients having metastasis to the anterior pituitary gland can present with panhypopituitarism or signs and symptoms of anterior pituitary gland dysfunction including corticotroph, gonadotroph, somatroph, and thyrotroph deficiency. One or more hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary gland could be deficient [22]. Primary adrenal insufficiency is an uncommon complication of malignancy that could result from metastasis to the adrenal glands. However, adrenal gland metastasis seldom causes adrenal insufficiency as at least 90% of the cortex must be destroyed to cause hormonal insufficiency. Secondary adrenal insufficiency is even a rarer complication of malignancy and mainly results from metastasis to the hypothalamus-pituitary gland axis [10]. Metastasis to the pituitary gland usually results in overactivation of the axis and so increased excretion of cortisol [10]. However, few cases of pituitary gland metastasis causing secondary adrenal insufficiency with various manifestations have been reported in the literature [10–17]. Five patients had lung cancer as the primary tumor and renal cell carcinoma, papillary thyroid cancer, and breast cancer were present as the primary tumor in one of each [10–17].

Hyperprolactinemia is also one of the possible presentations. Most cases of hyperprolactinemia occurring in the setting of pituitary metastasis are attributed to pituitary stalk effect. Our patient was noted to have an elevated prolactin level of 78 ng/mL, thus there was a very low suspicion for prolactinoma, as the prolactin level would be expected to be greater in prolactinomas [1,23]. Pituitary metastatic lesions could also compress the optic chiasm leading to visual field defects and ophthalmoplegia [7,9,19].

As previously mentioned, many cases of pituitary metastasis have been misdiagnosed as a pituitary adenoma [18]. The reason for this is the lack of clear radiological findings that distinguish between the 2 conditions. Current literature suggests several clues and radiological findings that could be helpful in differentiating between pituitary metastasis and pituitary adenomas. Certain MRI radiological features indicating pituitary metastasis are the presence of concurrent metastatic brain lesions, heterogeneous (or ring) contrast enhancement with loss of the normal hyperintense signal of the posterior pituitary lobe on T1 weighted sequences (T1W), rapid infiltration and growth, thickening of the stalk, invasion of the cavernous sinus, dumbbell shaped intersellar or suprasellar tumor, and sclerosis around the sella turcica [1,2,6]. It is worth mentioning that cavernous sinus invasion occurs only in 3–6% of pituitary adenomas [24]. The rapid onset of diabetes insipidus, ophthalmoplegia, and headache favors pituitary metastasis over pituitary adenomas [1]. Diabetes insipidus occurs in less than 1% of patients with pituitary adenomas [1]. Our patient presented with signs of hypopituitarism and headaches but did not have any evidence of diabetes insipidus. In the case of our patient, the diagnosis of pituitary metastasis was made based on the clinical picture and the aforementioned radiological findings as well as the presence of concurrent metastatic lesions in the brain and invasion of the cavernous sinus. This was all in the setting of the patient’s now confirmed primary lung cancer.

Treatment of pituitary metastasis is usually palliative, but again, dependent on the primary lesion. Local radiation, chemotherapy, and surgical options are available for palliative treatment, although studies have not shown any survival benefit to pursuing surgical options. Prognosis is dependent of the underlying primary tumor, but the mean survival in a patient with pituitary metastasis is reported as between 6–7 months [5,7,8].

Conclusions

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is a rare presentation of pituitary gland metastasis. The majority of pituitary gland metastasis cases presenting with secondary adrenal insufficiency have lung cancer as their primary tumor. Many cases of pituitary gland metastasis have been misdiagnosed as pituitary adenomas due to the lack of clear radiological findings that differentiate between these two conditions. However, it is important for physicians to be familiar with the radiological findings and presentations that could favor one diagnosis over the other.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Komninos J, Vlassopoulou V, Protopapa D, et al. Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: Case report and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):574–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fassett DR, Couldwell WT. Metastases to the pituitary gland. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16(4):E8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gsponer J, De Tribolet N, Déruaz JP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of pituitary tumors and other abnormal intrasellar masses. Retrospective analysis of 353 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999;78(4):236–69. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poursadegh Fard M, Borhani Haghighi A, Bagheri MH. Breast cancer metastasis to pituitary infundibulum. Iran J Med Sci. 2011;36(2):141–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sioutos P, Yen V, Arbit E. Pituitary gland metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3(1):94–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02409058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schubiger O, Haller D. Metastases to the pituitary – hypothalamic axis. An MR study of 7 symptomatic patients. Neuroradiology. 1992;34(2):131–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00588159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Max MB, Deck MD, Rottenberg DA. Pituitary metastasis: Incidence in cancer patients and clinical differentiation from pituitary adenoma. Neurology. 1981;31(8):998–1002. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.8.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita A, Meyer FB, Laws ER. Symptomatic pituitary metastases. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(1):69–73. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.1.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branch CL, Jr, Laws ER., Jr Metastatic tumors of the sella turcica masquerading as primary pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65(3):469–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah KK, Anderson RJ. Acute secondary adrenal insufficiency as the presenting manifestation of small-cell lung carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:pii. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-203224. bcr2013203224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmouch H, Arfa S, Mohamed SC, et al. An acute adrenal insufficiency revealing pituitary metastases of lung cancer in an elderly patient. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;23:34. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.34.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modhi G, Bauman W, Nicolis G. Adrenal failure associated with hypothalamic and adrenal metastases: A case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1981;47(8):2098–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sziklas J, Mathews J, Spencer R, et al. Thyroid carcinoma metastatic to pituitary [letter] J Nucl Med. 1985;26:1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckett DJ, Gama R, Wright J, Ferns GAA. Renal carcinoma presenting with adrenocortical insufficiency due to a pituitary metastasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998;35(4):542–44. doi: 10.1177/000456329803500410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouaziz H, Kaffel N, Charfi N, et al. Panhypopituitarism revealing metastasis of small-cell lung carcinoma associated with sarcoidosis. Ann Endocinol (Paris) 2006;67:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4266(06)72596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chamarthi B, Morris CA, Kaiser UB, et al. Stalking the diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(9):834–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps0806157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adashek ML, Miller K, Silpasuvan AA. EGFR T790M-positive lung adenocarcinoma metastases to the pituitary gland causing adrenal insufficiency: A case report. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2018;2018:2349021. doi: 10.1155/2018/2349021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YH, Lee BJ, Lee KJ, Cho JH. A case of pituitary metastasis from breast cancer that presented as left visual disturbance. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51(2):94–97. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kano H, Niranjan A, Kondziolka D, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary metastases. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(3):248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.06.003. discussion 255–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teears RJ, Silverman EM. Clinicopathologic review of 88 cases of carcinoma metastatic to the pituitary gland. Cancer. 1975;36(1):216–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197507)36:1<216::aid-cncr2820360123>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick PC, Post KD, Kandji AD, Hays AP. Metastatic carcinoma to the pituitary gland. Br J Neurosurg. 1989;3(1):71–79. doi: 10.3109/02688698909001028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pozzessere D, Zafarana E, Buccoliero AM, et al. Gastric cancer metastatic to the pituitary gland: A case report. Tumori. 2007;93(2):217–19. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Seters AP, Bots GT, van Dulken H, et al. Metastasis of an occult gastric carcinoma suggesting growth of a prolactinoma during bromocriptine therapy: A case report with a review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1985;16(6):813–17. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198506000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cottier JP, Destrieux C, Brunereau L, et al. Cavernous sinus invasion by pituitary adenoma: MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;215(2):463–69. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ap18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]