Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe cultural factors influencing African American mothers’ perceptions about infant feeding. Analysis of six focus group discussions of diverse African American mothers yielded sociohistorical factors that are rarely explored in the breastfeeding literature. These factors are events, experiences, and other phenomena that have been culturally, socially, and generationally passed down and integrated into families, potentially influencing breastfeeding beliefs and behaviors. The results from this study illuminate fascinating aspects of African American history and the complex context that frames some African American women’s choice about breastfeeding versus artificial supplementation feeding. This study also demonstrates the need for developing family centered and culturally relevant strategies to increase the African American breastfeeding rate.

Keywords: African American, Black, breastfeeding, infant feeding, culture

Introduction

African American mothers are among the least likely subpopulation to initiate breastfeeding, and negative health outcomes are prevalent from infancy to adulthood. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) reports that 64% of African American mothers initiate breastfeeding compared with 81.5% of non-Hispanic White mothers and more than 81.9% of Hispanic mothers. This occurs despite the recommendation that all babies, unless contraindicated, be breastfed for at least the first year of life (Eidelman et al., 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Low breastfeeding rates in the African American community are associated with negative health outcomes for the child, mother, and society (Bartick & Reinhold, 2010; Gartner et al., 2005). African American infant mortality rates are more than twice as high as infant mortality rates among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic groups (Khan, Vesel, Bahl, & Martines, 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health [OMH], 2015). Importantly, breastfeeding is associated with increased infant survival and decreased risks of common childhood illnesses, such as acute otitis media, respiratory infections, and asthma (Eidelman et al., 2012; Kull et al., 2010).

African American mothers are among the least likely sub-population to initiate breastfeeding, and negative health outcomes are prevalent from infancy to adulthood.

Breastfeeding, especially exclusively breastfeeding, is associated with positive health outcomes for mothers who breastfeed as well. African Americans have the highest morbidity and mortality rates from cancers (all types), diabetes, and influenza, and are prone to obesity; breastfeeding is associated with lower rates of these conditions (Gibbs & Forste, 2014; OMH, 2015; Victora et al., 2016). Additionally, Victora et al. (2016) estimate that breastfeeding could prevent 20,000 deaths from breast cancer among women. The association between breastfeeding and breast cancer risk is important because African American women diagnosed with breast cancer have higher mortality rates when compared with White women (Amend, Hicks, & Ambrosone, 2006; Victora et al., 2016). Increasing breastfeeding rates among African American women is a desirable goal and would contribute to overall health gains in this population and society.

African Americans also have relatively high rates of cardiovascular disease, low birth weight, preterm birth, and infant mortality (Giscombé & Lobel, 2005; Jones, 2000; Williams & Mohammed, 2013), which may stem from specific health behaviors (such as a lack of breastfeeding). These behaviors could be the consequence of historical racism (Asiodu & Flaskerud, 2011; Johnson, Kirk, Rosenblum, & Muzik, 2015; Mattox, 2012). In particular, African American women have had a collection of unique transformative events, which include racial, social, and political exclusions (Asiodu & Flaskerud, 2011; Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006; Johnson et al., 2015; Mattox, 2012; Reeves & Woods-Giscombé, 2015).

It has been difficult to raise the African American breastfeeding rate, and so several national initiatives have begun focusing upon historical/cultural influences on health-related behaviors, such as “The Cultural Framework for Health” developed by the National Institutes of Health, Healthy People 2020, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health initiative (Kagawa-Singer, Dressler, George, & Elwood, 2015; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2014; OMH, 2012). While the breastfeeding rate among African American women has, indeed, increased over the past three years, it still lags behind other racial/ethnic groups (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Review of the Literature

The authors conducted a literature review using the electronic databases PubMed, Women’s Studies International, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, and Google Scholar to find peer-reviewed journal articles published from 1984 to 2014. The following key words were searched for in the journal title or abstract: African American, Blacks, breastfeeding, lactation, wet-nursing, slave, slavery, artificial supplementation marketing, and disparity. These search terms were chosen so that information on African American women’s perceptions on breastfeeding and any sociohistorical factors related to breastfeeding might be identified. The database search yielded 47 relevant peer-reviewed articles, where relevance was independently assessed using thematic analysis and validated by the principal investigator (PI) and second author (CG). The review of these works revealed three major themes: (a) social influences on women who are less likely to breastfeeding; (b) the negative perceptions of breastfeeding that are associated with African American women not breastfeeding; and (c) the quality of breastfeeding information provided by health-care providers differs by the patients’ race (e.g., limited breastfeeding information) (DeVane-Johnson, Woods-Giscombé, Thoyre, Fogel, & Williams, 2017). There was limited research on sociohistorical factors that might explain why African Americans have the lowest breastfeeding rates among all ethnic/racial groups in the United States. Therefore, the goal of this study was to examine and describe cultural and sociohistorical factors influencing African American mothers’ perceptions about infant feeding. This study fills an important gap in the literature and seeks to advance ideas for reducing the breastfeeding disparity between African American women and other racial/ethnic groups.

Materials and Methods

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, six focus groups were convened between July 2015 and September 2015 in an urban area of North Carolina. The focus group model is appropriate for this study as we explored cultural, personal, and private topics such as African American women’s attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding infant feeding (Creswell, 2013; Mack, Woodsong, MacQueen, Guest, & Namey, 2005; Neergaard, Olesen, Andersen, & Sondergaard, 2009; Roulston, 2010; Sandelowski, 2000, Sandelowski, 2010). The focus group structure and format were guided by the principles of Krueger and Casey (2015) and Morgan and Krueger (1998) in phrasing engaging questions, thoughtful sequencing of questions, and anticipating the flow of the discussion.

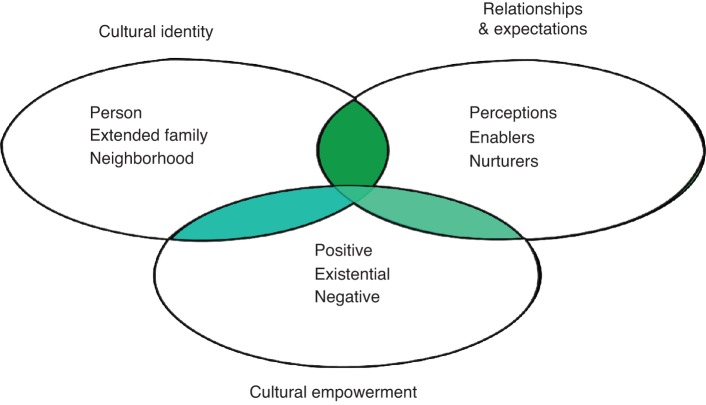

The PEN-3 model (see Figure 1) provided the theoretical basis for the structure of the questions. PEN-3 is a useful model for understanding the intersection of culture and health. The influence of one’s culture on health and health-related behavior has received increasing attention in recent years, led in part by the PEN-3 cultural model that directly incorporates cultural identity into understanding health behavior and developing interventions when that behavior is suboptimal (Airhihenbuwa, 2010; Kannan et al., 2009). The inclusion of cultural identity, cultural empowerment, and relationships within the PEN-3 framework (Figure 1) makes it particularly appropriate for this infant-feeding study. The PEN-3 model defines culture as a shared awareness that can reveal itself through speech and history by means of stories of a person’s life experiences (Airhihenbuwa & Liburd, 2006; Kannan et al., 2009). It provides a method for incorporating African American cultural and historical influences into the understanding of how individuals make health-care decisions. Moreover, the cultural component suggests that historical events and experiences may be complex, transformative, and influence attitudes and behaviors across long spans of time (Airhihenbuwa & Liburd, 2006).

Figure 1. PEN-3 model for understanding the intersection of culture and health (Airhihenbuwa & Webster, 2004).

Sample and Setting

A community-based sample of 39 African American women was recruited using purposive sampling, which resulted in the recruitment of African American women who were diverse in age, educational backgrounds, and socioeconomic status (SES). All participants in this study met the inclusionary criteria described in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion Criteria.

| 1. Women who self-identify as African American. |

| 2. Women 18 years old and older. |

| 3. Women who have experienced giving birth to a full term infant. |

| 4. Women who have completed at least one year of education after high school. |

The six focus groups were divided into three artificial supplementation-feeding groups and three breastfeeding groups based on age: 18–29, 30–50, and 51 and over. Participants that breastfed for less than 2 weeks were assigned to the artificial supplemtation-feeding groups, and all others were assigned to the breastfeeding groups. In the case of multiple children with multiple feeding methods, the method used most or longest was the deciding factor, and the PI made the final decision on participant group placement. Four of the six focus groups were held in the lobby of a hair salon after hours. The other two focus groups were held in a private room at two area libraries. All three spaces were private and comfortable.

Procedure

Five methods were used to recruit participants into the study (as described in Table 2): fliers, snowball sampling, churches, hair salons, and Mocha Moms breastfeeding support groups. Before any PI–participant interaction, the participants gave both oral and written informed consent. Participants received a $25 gift card to Target for participating, which was consistent with compensation of similar studies (Ripley, 2006).

Table 2. Sampling Techniques.

| 1. Fliers: Study fliers were posted at local OB/GYN offices, university campuses, African American churches, hair salons, and community settings such as public libraries. The fliers provided the basic study information and contact information for possible participation in the infant-feeding study. |

| 2. Snowball sampling: Snowball sampling allows a participant to refer others within their network that may fit the study inclusion criteria (Creswell, 2013). After participants were screened, found to be eligible, and invited to participate, the PI then told them to refer any friends or associates that they thought might be interested in being a participant. |

|

Sites 1. Churches: Recruiting participants from African American churches is an effective way of recruiting African Americans for research studies (Carter-Edwards, Fisher, Vaughn, & Svetkey, 2002; Hatch & Voorhorst, 1992; Taylor, 2009). The PI has a congregational relationship with several African American churches. She contacted the pastor and asked permission to recruit members of the church to participate in the study. The PI made an announcement about the importance of the study during church service. Additionally, a copy of the study flier was printed in the church bulletin every Sunday for three months. |

| 2. Hair salons: The PI has a personal relationship with hair salon owners who gave oral and written approval for the PI to recruit in their establishment. When the PI was not on site, hair stylists would talk to their clients about the infant-feeding study and get their name and number for the PI to contact them if they were interested. |

| 3. Local Mocha Moms breastfeeding group: The PI reached out to the local Mocha Moms breastfeeding group, which is a breastfeeding support group for mothers of color in the local area. A member of the group passed along the study information to the other members of the group, asking them to participate in the infant-feeding study. |

PI = principal investigator.

The PI used a prepared focus group discussion guide to obtain rich responses, to probe appropriately based on the participants’ responses, and to generate continued discussion within the group (Krueger & Casey, 2015; Sandelowski, 2010). The focus group questions are provided in Table 3. It is important to note that during the focus groups the PI did not prompt participants with examples or pictures to obtain any of the responses that are noted in the “Results” section.

Table 3. Sample Questions.

| Could each of you tell me about how you decided how you were going to feed your baby (babies)? |

| Do you think there are any cultural factors—things that we learned from our parents and relatives—that influence African American women and their decision whether or not to breastfeed? |

| What, if any, cultural or historical factors influenced your decision to or ability to breastfeed and/or formula-feed? |

| Can you tell me about what you heard about breastfeeding from older relatives? |

| What comes to mind when you hear the word “breastfeeding”? |

In this study, the lead moderator and PI was an African American female in her 40s with 18 years of experience providing breastfeeding support and care for women. A second moderator trained in qualitative methods was in attendance that assisted with participant check-in and served as note-taker. The second moderator was one of two African American females aged 26 and 45 years. When the PI, moderator, and participants share certain characteristics, like gender and ethnicity, the quality of the data collection is enhanced (Collins, 2000; Thomas, 2004).

Data Analysis

The focus groups were audio recorded, de-identified, transcribed professionally, and uploaded to a password-protected computer (Sandelowski, 1994). Descriptive summaries were created for each transcript, summarizing participants’ infant feeding decision-making processes and influences as well as notes from the PI and note takers regarding observations made of nonverbal cues (Sandelowski, 1994). A thematic analysis was used to evaluate the data and identify themes throughout the participant narratives using the qualitative computer software program MaxQDA (Morgan, 1988; Morse & Field, 1995). Once the transcripts were verified, the PI started with a line-by-line reading of the transcripts starting with focus group one, then the PI attached codes. As a strategy to increase legitimacy, the PI used a second coder trained in qualitative methods to code a subset of data after the first focus group, to generate a codebook and to start comparing codes. The responses were coded based on the recurrence of phrases supported by transcript excerpts as evidence. To refine the codes, the PI and coders compared codes and reconciled any differences and then moved on to the second focus group. The PI utilized this process for each focus group, and once all codes were established, code categories were developed. From code categories, code themes were developed from matrices (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Lastly, the interpretive phase involved assessing the larger meaning and conceptual significance of the codes and code-connections (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) in the development of themes, which is a statement of some relevant aspect of a person’s experience. The themes are presented as the results and answers to the specific aims.

The analysis process was data-driven and participant-centered to allow identification of concepts that perhaps the researcher was unaware of when the study was designed (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The researcher used the participants’ own language and insights to direct the analysis, rather than using theory or a conceptual framework to provide a priori data codes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The participant responses were compared within the same focus groups (breastfeeding and artificial supplementation) and across groups (breastfeeding versus artificial supplementation). Exemplar quotations are included from the narrative data emphasizing participants’ thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs about their infant-feeding choice (Roulston, 2010). Once themes were identified, the meaning and significance of the themes from the data were interpreted (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This analytic process assessed the dynamic cultural context of how African American history and culture are connected to infant feeding decisions.

The PI consulted with an expert in the field of African American history and with an advisory committee when reviewing the transcripts to ensure validity and credibility (Sandelowski, 1993). To ensure confirmability, the PI provided an interpretation of the participants’ responses along with quotes from the transcripts (Roulston, 2010). The PI and second moderator maintained field notes and debriefed after each focus group to assess consensus and increase legitimacy (Morgan & Krueger, 1998).

Results

Demographic Data

Each participant completed a demographic survey consisting of age, marital status, highest level of education, and total income. Participant ages ranged from 19 to 87 years; the median age was 53 years. See Table 4 for a summary of all demographic information.

Table 4. Focus Group Demographic Data.

| Total N = 39 | Artificial Supplementation | Breastfeeding |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 16 (41%) | 23 (59%) |

| Marital status N (% of group) | ||

| Married | 7 (44%) | 17 (74%) |

| Single | 5 (31%) | 5 (22%) |

| Divorced/separated | 3 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| Widowed | 1 (6%) | 1 (4%) |

| Education N (% of group) | ||

| Some college | 7 (44%) | 10 (44%) |

| Associates degree | 5 (31%) | 4 (17%) |

| Bachelors degree | 2 (13%) | 3 (13%) |

| Some post-secondary | 2 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| Masters degree | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) |

| Doctoral degree | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) |

| Employment N (% of group) | ||

| Full time | 12 (75%) | 11 (47%) |

| Part time | 1 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| Self-employed | 2 (13%) | 2 (9%) |

| Housewife | 0 (0%) | 5 (22%) |

| Retired | 1 (6%) | 3 (13%) |

| Income N (% of group) | ||

| <$20,000 | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

| $20,000–35,000 | 4 (25%) | 3 (13%) |

| $36,000–50,000 | 5 (31%) | 4 (17%) |

| $51,000–75,000 | 4 (25%) | 4 (17%) |

| $76,000–100,000 | 2 (13%) | 3 (13%) |

| $100,000+ | 1 (6%) | 5 (22%) |

| No answer | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

Qualitative Focus Group Results

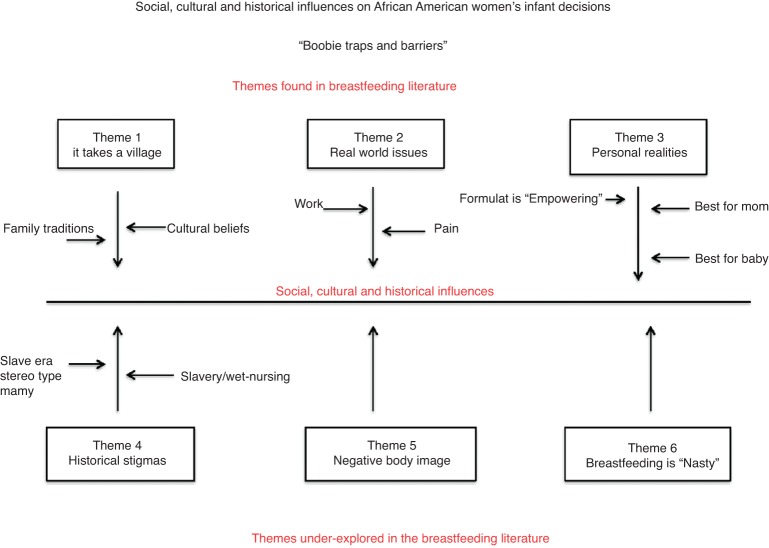

Analysis of the qualitative focus group data resulted in the identification of an overall theme “Boobie Traps and Barriers” and six underlying themes (see Figure 2). The first three themes (It Takes a Village, Real World Issues, and Personal Realities) have been identified and explored in previous research and are described in Section I. Section II describes the second three themes (Historical Trauma, Negative Body Image, and Breastfeeding as “Nasty”) are either nonexistent or underexplored in the current breastfeeding literature (see Figure 2). The themes identified reflect that there are obstacles and difficulties in the lives of some African American women at the intersection on race and class that potentially made the decision to breastfeed difficult. One, two, or all of the themes found influenced the way participants in this study made their infant feeding decision.

Figure 2. Social, cultural, and historical influences on African American women’s infant feeding decisions.

Section I: Themes Found in the Existing Breastfeeding Literature

Theme I: It Takes a Village

Culture and traditions contribute to how African American women make infant-feeding decisions. Breastfeeding is a learned and mimicked activity; therefore, how a woman is socialized around infant feeding shapes her decision to breastfeed or not (Mojab, 2006). One woman in the 18–29 age artificial supplementation-feeding group discussed how her upbringing and cultural traditions influenced her infant-feeding choice with the following sentiment: “I grew up thinking breastfeeding was a White thing, I never saw a Black woman breastfeed.”

Another participant in the age 18–29 group stated, “But it's just my aunts are old-fashioned. They’re just like, ‘no you’re not doing that,’ so we're not allowed to do it in front of family members.” This statement shows that in some families, if a woman defies her family’s tradition of artificial supplementation feeding, instead choosing to breastfeed, there are consequences. This mother was in some ways given an ultimatum; if she breastfed her child she would have to avoid being around her family. Certainly, this situation could make the breastfeeding woman feel ostracized, and she may second-guess her decision to breastfeed.

In this study, generationally persistent traditions were noted among participants. One participant in the 30–50 artificial supplementation-feeding focus group discussed the impact of generational traditions on her infant-feeding choice with the following statement: “Everyone in my family bottle feeds, it’s just been generationally. That is the way Grandma did it and it continued.” Similarly, a participant in the 51 and over breastfeeding group had support from her family: “I had a mother and aunt that was there to coach me, and they were saying that the breast milk was better than the formula.”

However, most women reported not having direct conversations about infant feeding with family members. In fact, when participants were explicitly asked about the conversations that they had with their family about how they were going to feed their babies, 35 out of 39 participants stated they had “no conversations” at all. One participant in the 18–29 age artificial supplementation-feeding group shared that it was a given in their family that bottle feeding was the only option, “bottles were just natural” and no conversations were needed. Another participant in the 30–50 age breastfeeding group shared that not only did her family avoid discussing infant feeding, there also were no conversations about breasts at all, “no conversations, you don’t talk about your boobs.” Only four participants stated that they discussed their infant-feeding choices with their mothers, grandmothers, aunts, or other relatives. A mother in the 18–29 age breastfeeding group shared, “The most conversation we had in our family about feeding is the best bottle to buy, glass versus plastic.”

Theme II: Real World Issues

The second theme that emerged from the focus groups incorporates two subthemes: issues related to work and pain. Work and pain of breastfeeding is described in the literature as reasons to either not breastfeed or wean early (Fischer & Olson, 2014; Ogbuanu et al., 2009; Ware, Webb, & Levy, 2014). The results of this study found similar findings. Participants shared that various realities of life affected their decisions about infant feeding, including work-related challenges and pain with breastfeeding.

Work

A recurrent subtheme that emerged when talking with women of all ages was that the practical and logistical constraints of working and breastfeeding were problematic. An over 51 breastfeeding participant who stopped breastfeeding when her infant was six months old exemplifies the difficulties of working while breastfeeding. She stated,

I stopped breastfeeding before I went back to work. I went back to work after six months. And so that was one of the criteria I had for going back to work was to get her weaned. I made sure I had my stuff in order before I went back to work, so I didn’t have that to deal with.

Relatedly, a artificial supplementation-feeding participant aged 30–50 stated, “I think that I feel more working moms, a lot of us really couldn’t breastfeed but I think by us being working, we didn’t really have a choice to breastfeed.” A 30–50-year-old breastfeeding participant stated, “women working and breastfeeding, you are at a disadvantage because then it’s almost like a crutch.” Other women described an inability to advance in their workplace while pumping or unwillingness by the company to provide a space and storage for breastmilk. There were statements shared by two breastfeeding participants aged 18–29 and 30–50 that illustrate how some employers did not support breastfeeding. “I was asked by a senior female consultant with no kids at my firm when I was pregnant, are you going to be an A + employee and a C + mom or a C + employee and an A + mom?” Another stated, “There was a problem with my employer. He never provided somewhere to pump my milk. And then when I did get somewhere to pump my milk, they would pour it out because they said it couldn't be in the refrigerator.”

Pain

While both groups discussed the challenges associated with managing the pain of breastfeeding, the artificial supplementation feeders described this as a reason for choosing formula. An 18–29-year-old formula-feeding participant reported, “I guess my boobs were really sore, so when my baby started to suck on them, they were really tender, so I stopped, I didn’t want him to be on me.” However, the breastfeeding mothers “pushed through” it, stating that they continued to prioritize what (they thought) was best for the baby. A participant aged 30–50 stated,

Culture and traditions contribute to how African American women make infant-feeding decisions. Breastfeeding is a learned and mimicked activity; therefore, how a woman is socialized around infant feeding shapes her decision to breastfeed or not.

I mean, it hurts badly, it was tough. I got scales on it and it was bad. And I didn’t have anybody to talk to about it, I mean, I sort of suffered through it, I got through it on my own, but it was tough. I just remember it hurting really badly and thinking, I don’t know whether I can do this, but I stuck to it and I got through it.

Theme III: Personal Realities

This theme consisted of participants’ reasons and justifications for their infant-feeding choice. There were three subthemes: best for mom, best for baby, and choosing artificial supplementation because it was empowering. Also, related to this last subtheme, was the belief that artificial supplementation was better than breastfeeding.

These subthemes reflect distinct differences between the two groups when asked, “What were some of the factors that influenced your decision to breast/formula feed?”

Best for Mom

The “best for mom” rationale was predominately expressed by women from the artificial supplementation-feeding group. Not surprisingly, few of the formula-feeding participants discussed the benefits of breastfeeding. They mainly discussed the negative aspects and barriers of breastfeeding, as exemplified by the statement by a participant aged 30–50, “I wanted a little bit of freedom, [the] bottle easier” and an artificial supplementation-feeding participant aged 18–29 who stated, “I wanted to make sure someone else could help.” Along the same lines is a statement by an over-51 artificial supplementation-feeding participant, “bottle feeding was easier and more convenient.”

Best for Baby

Breastfeeding participants discussed considering what was best for baby in their infant-feeding choices. The breastfeeding mothers all stated the positives and benefits of breastfeeding for them and the baby, such as “breast milk adjusts based on the needs of the baby. I want to be as natural as possible, I do not know what is in formula,” and “I wanted to give him the best start in life.” Another breastfeeding participant stated, “After doing some research I learned the sucking motion causes the brain and the skull to develop in a certain way.”

Some said that breastmilk was inadequate and that their babies needed more to eat. Adding cereal to an infant’s bottle was discussed in both the formula and breastfeeding groups. Across all three age groups, most of the formula participants considered adding cereal and food in the bottle. The timing varied from as early as two weeks to four months. The reasons for adding cereal varied; a statement by an artificial supplementation participant aged 18–29 stated, “I started cereal at two weeks old, so he would sleep. I mixed formula, cereal, Karo syrup, just to make sure that they didn’t get constipated, and just mix it all together.” Others stated being advised to mix cereal with artificial supplementation by family members, such as this statement by another 18–29-year-old artificial supplementation-feeding participant, “My mother pretty much told me if they weren’t sleeping at night or within the first week, to go ahead and put cereal in their bottle.” However, there was only one breastfeeding participant aged 18–29 who stated that she added food to her baby’s bottle, “I used to take a little bit of baby food and I mix it in their milk and shake it up and let them drink it, like peas, sweet tomatoes, carrots and they drink it.”

Artificial Supplementation as a Sense of “Empowerment”

Social messaging, mainly through formula advertisement, could associate artificial supplementation feeding with a sense of empowerment. For many women, formula feeding was communicated as normal, convenient, and natural. Conversely, some participants felt “disempowered” by the idea of breastfeeding. One participant in the over-51 formula-feeding group shared, “There was an empowerment in being able to choose that bottle and not say I’m going to be sitting here with the baby attached to me. I’m just going to do the bottle thing and just be done with it.” A breastfeeding group participant aged 30–50 stated,

I know Black women who felt like they don’t want to do anything else that was outside of their Blackness. It’s enough that you already have the spotlight because you are Black. If you are Black and you nurse, it’s an additional, “Oh my gosh look at that person with that baby.

Participants in the artificial supplementation feeding group shared additional examples about how choosing to artificial supplementation feeding was empowering because artificial supplementation was comparable or superior to breastmilk, such as this statement from an over-51 formula-feeding participant,

There’s newer formulas that can replicate what’s coming out of me. I have a choice today. I don’t have to work in someone’s house and clean. I don’t have to breastfeed if I don’t want to, so I choose not to breastfeed. That sort of empowered myself to make my own decisions.

Another participant in the over-51 artificial supplementation-feeding group stated,

At the time when I was having my kids they had good milk out there like Enfamil and Similac. That’s when I decided to feed my kids with the bottle. Plus, I love washing the bottles out, filling them up with milk, putting them in the refrigerator, and just stand about and look at them. It was just something about that I just love.

When participants were asked about current formula marketing, one participant in the 30–50 formula-feeding group stated, “I had formula at my house before I had a baby in the house. Formula companies sent it.” A breastfeeding participant in the same age group had a similar experience, stating, “They gave me samples of formula and were just like, ‘Hey, if it doesn’t work out. You know’.”

One breastfeeding over-51 participant remembered a artificial supplementation company ad that communicated the idea that formula feeding was a more empowering and healthy option than breastfeeding.

I do remember the advertisement for PET and Carnation and about the healthy babies and all of that. With the Fultz quadruplets, I just felt that they were promoting more so the product more so than the health of the infant, the child. That was my perception of that taking off, where more people decided not to breastfeed because of the image of the quadruplets and their appearance of their looks, and thinking that that would make their babies look better or healthier instead of breastfeeding.

It was clear that for some women, artificial supplementation is considered an acceptable, even desirable, way to feed a baby. However, none of the participants in the 18–29 age group mentioned any artificial supplementation-marketing tactics.

Section II: Themes UnderExplored in the Breastfeeding Literature

Theme IV: Historical Stigma

Negative historical influences associated with breastfeeding may produce unconscious biases in the African American community, which perhaps conflict with their own overt intention. African American history allows contextualization of current health behaviors that are linked to marginalization and subjugation. Throughout history, stereotypes were developed and used to mask the humanity of the subjugated and to justify cruel treatment of disadvantaged populations; these stereotypes are still in existence today (Blassingame, 1972; Fox-Genovese, 1988; White, 1999). When participants were asked, “Do you think there is anything historical that happened a long time ago in African American history that affected your decision to breast or formula feed?” Participants described two distinct sociohistorical influences: slave-era wet-nursing and the slave-era “mammy” stereotype. Participants reported these influences without any kind of prompting from the researcher. Most responses about sociohistorical influences were from the older generation of participants (51 or over). Yet there were responses from the 18–29 and 30–50 breastfeeding participants as well.

Slavery andSlave-EraForcedWet-Nursing

Participants shared their thoughts about slavery and slave-era wet-nursing and how this influenced their perceptions about breastfeeding. A breastfeeding participant age 18–29:

The stealing of the breast milk from the slaves. They put them down on their stomach and they will squeeze their breast onto the jugs until they were empty. They would put the slave lady in the position to where they could not hurt the babies because they need strong workers to come and they would just literally squeeze their milk, their breast until the breasts were empty.

Another over-51 artificial supplementation participant stated:

Breastfeeding was what they had to do because the economy at that time for Blacks wasn’t that good. So mother, she breastfed because she had to. This day and time Black women have a better choice. So that’s why I chose to bottle-feed, because I did have a better choice. In reference to economics, I have a better choice. I could bottle-feed my children instead of breastfeeding.

One breastfeeding participant age 30–50 shared the following:

Some just associate breastfeeding with slavery, wet-nursing, and the lack of choice. And so, they feel like a formula will be like a step up, the whole economics. And so you’re not a slave, I’m not going to be no baby touching me like that and trying to dissociate themselves.

Slavery-EraStereotypes

Data from the present study indicate that slavery era stereotypes such as “mammy” (the wet-nurse) did influence the older generation of women to not engage in breastfeeding. One over-51 artificial supplementation-feeding participant stated,

That image of a “mammy” when people would say that, it did conjure up those pictures of the women feeding the White babies and all of that. Because a White man said to me one day, “Tell your mammy I said hello.” That was one of the influential words that I heard.

Theme V: Negative Body Image

How a woman feels about her breasts plays an important role in her decision to breastfeed. Breast-related self-esteem issues and body image issues impacts infant-feeding decisions. Participants in this study told of developing breasts at a young age and trying to hide them due to fear of getting teased or verbally sexually harassed by boys. Some participants voiced not liking their breasts and always trying to hide or cover up their breasts, which did not produce a positive foundation for relating to their breasts in a way that promoted or facilitated breastfeeding. For example, when asked, “Tell me how you felt when you started developing breasts,” one participant stated:

I never wanted them (breasts), I still have a problem with it. I always want a breast reduction and I have minimizer bras because I don’t like myself with big breasts. That’s probably one of the reasons I really didn’t want to breastfeed.

Another participant stated, “I was not happy with my breasts. I got boobs early and I would hunch to try and hide them.”

However, one artificial supplementation group participant age 30–50 shared her satisfaction with her breasts because they were large, yet she reported disappointment that they did not produce milk, “I prayed to God every night for big breasts. I really do love my breasts. I just wish they would have done right for my babies.”

Theme VI: Breastfeeding Described as “Nasty”

The description of breastfeeding as “nasty” was shared in both the artificial supplementation and breastfeeding groups. Webster’s dictionary defines “nasty” as highly unpleasant, especially to the senses, physically nauseating. Synonyms for the word “nasty” are disgusting, dreadful, and horrible. One might ask how an act that is natural and biologically functionally can be described in this way. One bottle-feeding participant over 51 shared, “I chose to bottle-feed because I thought breastfeeding was nasty.” Another artificial supplementation-feeding group participant age 30–50 stated, “I thought it was nasty like ‘Ooh, she got the baby sucking her breast!’” One woman in the 18–29 age breastfeeding group said she received messages from her family that breastfeeding was “nasty”:

“Breastfeeding is like taboo. I have a sister that’s older than me and when she found out that I was breastfeeding I wasn’t allowed to do it at her house because she said it was nasty.”

Discussion

This study examines African American mothers’ thoughts and attitudes about infant feeding. The results here that are underexplored in the breastfeeding literature indicate that African American culture, traditions, and history play a contextual role in making infant-feeding decisions. There is important knowledge to be gained from examining African American history and the evolution of breastfeeding, which may help to increase the African American breastfeeding rate today. Results from this study are consistent with others who have asserted that certain aspects of African American history (e.g., slave-era stereotypes and wet-nursing) dismantled traditional breastfeeding practices and negatively affected breastfeeding in the African American community (Asiodu & Flaskerud, 2011; Johnson et al., 2015; Mattox, 2012).

There is important knowledge to be gained from examining African American history and the evolution of breastfeeding, which may help to increase the African American breastfeeding rate today.

In this study, certain aspects of African American history such as slavery, wet-nursing, and the mammy stereotype did persuade some artificial supplementation participants over 50 not to breastfeed. Historically, stereotypes have been used to justify cruel treatment of disadvantaged populations. Often, the dominant group in a population justifies abusive actions toward the nondominant group by associating that group with negative behaviors and attributes. During slavery, White slave owners imposed degrading labels on Black slaves. A concept known as “stereotype threat” asserts that negative stereotypes can inhibit behaviors for fear of conforming to the presumed stereotype (Ambady, Paik, Steele, Owen-Smith, & Mitchell, 2004). By not engaging in certain behaviors (here, breastfeeding) that are linked to a negative stereotype (here, the wet-nurse slave), individuals might distance themselves so that they are not judged negatively or become self-associated with that stereotype (Ambady et al., 2004).

Sociohistorical events could drive attitudes of breastfeeding today due to a common shared experience in the Black culture that is kept alive in the oral histories and attitudes of African American women (Alexander, 2004). Older family matriarchs (e.g., mothers and grandmothers) may have negative thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs about breastfeeding and a preference for artificial supplementation feeding. It is reasonable to postulate that the institution of slavery could have dismantled traditional breastfeeding practices for Black women and may explain why breastfeeding rates among African American mothers today are below those of populations that were not exposed to forced wet-nursing or mammy stereotypes.

Historical life experiences of African American women are a collection of racial, social, and political exclusions (Geronimus et al., 2006). Cultural stigmas, as well as racial and institutional discrimination, have had deleterious effects on health behaviors in the African American community (Jones, 2000; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Results from this study suggest that these historical factors extend to breastfeeding.

Findings related to the influence of breast-related body image and shame of breasts are important to note when attempting to understand breastfeeding disparities. African American women, especially older African American women, may be more socialized to view breasts as private and not to be exposed (Bentley, Dee, & Jensen, 2003; Higginbotham, 1993). It is possible that cultural preferences for modesty may influence breastfeeding decision-making. Interventions that facilitate privacy for those who would be more comfortable using covers or shawls to breastfeed may be more beneficial. Moreover, there is a need for interventions that target issues related to body image; breast “appreciation” could help African American women to become more comfortable with their breasts and address negative body image challenges that exist.

The reports of the focus group participants regarding breastfeeding as “nasty” were compelling and need further investigating. Although there has not been a great deal of research on this topic, findings from this study corroborate others who have suggested it as a potentially important factor in breastfeeding disparities (Cricco-Lizza, 2004; Hannon, Willis, Bishop-Townsend, Martinez, & Scrimshaw, 2000). Some music videos exploit women by emphasizing their breasts as sexual and erotic to men (Ward, Merriwether, & Caruthers, 2006), thus perpetuating a negative image of female breasts. Perhaps the problem could be that breasts themselves are oversexualized in the media and viewed as sexual rather than functional for nutrition, and therefore breastfeeding as a biological activity is discounted. More research is needed to comprehensively explore this concept among African American women and how this perception may contribute to artificial supplementation feeding. Additional research on perceptions of breastfeeding as nasty may reveal important elements for the development of successful interventions negating the ‘nasty’ perception, ultimately promoting breastfeeding.

Strengths and Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to explore the influence of culture and history on African American women’s thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs about infant feeding. This study contributes to the existing literature by examining the influence of African American history on infant-feeding choices. The participants in this study included African American women with cultural roots from the Southern United States with varying age, marital status, education, and income levels. However, all the participants lived in North Carolina. Therefore, the sample is not representative of African American women in other geographical or cultural locations

Certain aspects of African American history (e.g., slave-era stereotypes and wet-nursing) dismantled traditional breastfeeding practices and negatively affected breastfeeding in the African American community.

Implications for Practice

The breastfeeding disparity between African Americans, non-Hispanic White, and Hispanic Americans is a public health crisis. Findings from this study could directly benefit how women’s health providers approach breastfeeding in the African American community. It is critical for lactation consultants, nurse scientists, global health workers, and health-care providers to be aware of the unique cultural and historical phenomena that exist for African American women when compared to other racial or ethnic populations. If health-care professionals are armed with an awareness of specific cultural and sociohistorical influences that impact infant feeding decisions, while also prioritizing individualized care for African American women, health-care workers can avoid cultural or racial stereotypes that limit their ability to provide the highest quality of services.

This study’s findings as well as others support initiatives for more diverse lactation consultants, peer counselors to initiate and support continued breastfeeding in African American women led by African American women such as the Reaching Our Sisters Everywhere programs and The Black Mother’s Breastfeeding Association and other community based breastfeeding support groups (Green, 2012; Lutenbacher, Karp, & Moore, 2016; Mickens, Modeste, Montgomery, & Taylor, 2009; Spencer, Wambach, & Domain, 2015). Perhaps women with similar traditions and cultural beliefs may be more apt to trust and confide in women who looked like them. These types of support groups instill a sense of camaraderie and build a stronger African American community and infrastructure for support to increase the African American breastfeeding rates. The women reportedly were more apt to trust and confide in women who looked like them

A unique finding of this study is that some African American women may make infant feeding decisions within a unique sociohistorical context that may implicitly or explicitly discourages breastfeeding. The awareness of historical influences that impact breastfeeding attitudes and behaviors will aid in culturally sensitive breastfeeding promotion and education. It is also important to note that although there may be a collective historical narrative that is similar, each African American woman enters motherhood with her own set of beliefs that are based on her lived experiences, including how she was raised. Developing interventions like those conducted by Grassley, Spencer, and Law (2012), tailored to African American grandmothers and other matriarchs (older women who are influential in young mothers’ lives) could educate them on breastfeeding benefits, while at the same time illuminating historical perceptions that play a part in their perception of breastfeeding. Similarly, there is a need for interventions that expose young African American women to the sociohistorical factors that influence breastfeeding rates to see if this affects infant-feeding decisions. Arming health-care workers and childbirth educators with knowledge of cultural and sociohistorical factors that impact infant-feeding decisions could improve rates of breastfeeding in the African American community.

Conclusion

The low breastfeeding rate among African Americans is a public health crisis. A woman’s rationale for her infant-feeding decision is personal and complex. Despite previous research on racial disparities in breastfeeding, the cause of this phenomenon has been poorly understood. This study’s findings illuminate the potential contributions of generational, cultural, and historical factors. In addition, findings from the current study corroborate previous research findings that family and social factors influence breastfeeding decision-making. The factors found by this study are critical for culturally relevant and effective intervention designs. Using a theoretical framework such as the PEN-3 can assist in developing culturally sensitive methodologies to address health disparities by examining health and culture in a holistic way. Additionally, there are benefits to expanding a woman’s consciousness about specific aspects of African American history that influence their personal decisions to breastfeed. More specifically, educating women about factors within their community that contribute to preferences for artificial supplementation, and explaining the idea of cultural and sociohistorical influences are important components to interventions that promote breastfeeding. This may eventually contribute to higher rates of breastfeeding and longer durations of breastfeeding in the first year of life. With breastfeeding and all other health promotion initiatives, there should not be a one-size-fits-all approach to interventions and initiatives aimed at decreasing the breastfeeding disparity. This would leverage significant health benefits for the African American population.

Acknowledgments

The Carolina Global Breastfeeding Institute, Kellogg Foundation, and the National Service Pre-doctoral Fellowship Award, NRSA/NIH/NINR Grant NR007091 Interventions for Preventing and Managing Chronic Illness supported this work. Many thanks to David Banks, Karen Sheffield, Nakia Best, Sherita Johnson, and Kayoll Galbraith for their help with this study, as well as qualitative expert Paul Mihas.

Biographies

STEPHANIE DEVANE-JOHNSON is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at Duke University.

CHERYL WOODS GISCOMBE is an associate professor in the School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

RONALD WILLIAMS II is an assistant professor in the African, African American and Diaspora Studies Department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

CATHIE FOGEL is a professor Emeritus in the School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

SUZANNE THOYRE, is a professor in the School of Nursing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

REFERENCES

- Airhihenbuwa, C. O. (2010). Culture matters in global health. The European Health Psychologist, 12(4), 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa, C. O., & Webster, J. D. (2004). Culture and African contexts of HIV/AIDS prevention, care and support. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 1(1), 4–13. 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, J. C. (2004). Cultural trauma and collective identity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa, C. O., & Liburd, L. (2006). Eliminating health disparities in the African American population: the interface of culture, gender, and power. Health Education & Behavior, 33(4), 488–501. 10.1177/1090198106287731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambady, N., Paik, S. K., Steele, J., Owen-Smith, A., & Mitchell, J. P. (2004). Deflecting negative self-relevant stereotype activation: The effects of individuation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 401–408. 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amend, K., Hicks, D., & Ambrosone, C. B. (2006). Breast cancer in African-American women: Differences in tumor biology from European-American women. Cancer Research, 66(17), 8327–8330. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiodu, I., & Flaskerud, J. H. (2011). Got milk? A look at breastfeeding from an African American perspective. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(8), 544–546. 10.3109/01612840.2010.544842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartick, M., & Reinhold, A. (2010). The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: a pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics, 125(5), e1048–e1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartick, M. C., Schwarz, E. B., Green, B. D., Jegier, B. J., Reinhold, A. G., Colaizy, T. T., et al. Stuebe, A. M. (2017). Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: Maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Maternal & child nutrition, 13(1). 10.1111/mcn.12366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, M. E., Dee, D. L., & Jensen, J. L. (2003). Breastfeeding among low income, African-American women: power, beliefs and decision making. The Journal of Nutrition, 133(1), 305S–309. 10.1093/jn/133.1.305S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blassingame, J. W. (1972). The slave community: Plantation life in the antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Edwards, L., Fisher, J. T., Vaughn, B. J., & Svetkey, L. P. (2002). Church rosters: is this a viable mechanism for effectively recruiting African Americans for a community-based survey? Ethnicity & Health, 7(1), 41–55. 10.1080/13557850220146984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Breast-feeding report card: Progressing towards national goals. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cricco-Lizza, R. (2004). Infant-feeding beliefs and experiences of Black women enrolled in WIC in the New York metropolitan area. Qualitative Health Research, 14(9), 1197–1210. 10.1177/1049732304268819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVane-Johnson, S., Woods-Giscombé, C., Thoyre, S., Fogel, C., & Williams, R. (2017). Integrative literature review of factors related to breastfeeding in African American Women: evidence for a potential paradigm shift. Journal of Human Lactation, 33(2), 435–447. 10.1177/0890334417693209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidelman, A. I., Schanler, R. J., Johnston, M., Landers, S., Noble, L., Szucs, K., Viehmann, L., & Section on Breastfeeding. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T. P., & Olson, B. H. (2014). A qualitative study to understand cultural factors affecting a mother's decision to breast or formula feed. Journal of Human Lactation, 30(2), 209–216. 10.1177/0890334413508338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Genovese, E. (1988). Within the plantation household: Black & White women of the South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, L. M., Morton, J., Lawrence, R. A., Naylor, A. J., O'Hare, D., Schanler, R. J., Eidelman, A. I., & American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. (2005). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 115(2), 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, B. G., & Forste, R. (2014). Socioeconomic status, infant feeding practices and early childhood obesity. Pediatric Obesity, 9(2), 135–146. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giscombé, C. L., & Lobel, M. (2005). Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: The impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychological Bulletin, 131(5), 662–683. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassley, J. S., Spencer, B. S., & Law, B. (2012). A grandmothers’ tea: evaluation of a breastfeeding support intervention. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 21(2), 80–89. 10.1891/1058-1243.21.2.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, K. (2012). 10 must-dos for successful breastfeeding support groups. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7(5), 346–347. 10.1089/bfm.2012.0071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, P. R., Willis, S. K., Bishop-Townsend, V., Martinez, I. M., & Scrimshaw, S. C. (2000). African-American and Latina adolescent mothers’ infant feeding decisions and breastfeeding practices: a qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(6), 399–407. 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch, J. W., & Voorhorst, S. (1992). The church as a resource for health promotion activities in the black community D. M. Becker (Ed.), Health behavior research in minority populations: Access, design, and implementation. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, E. B. (1993). Righteous discontent. The women’s movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A., Kirk, R., Rosenblum, K. L., & Muzik, M. (2015). Enhancing breastfeeding rates among African American women: A systematic review of current psychosocial interventions. Breastfeeding Medicine, 10(1), 45–62. 10.1089/bfm.2014.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa-Singer, M., Dressler, W. W., George, S. M., & Elwood, W. N. (2015). The cultural framework for health: An integrative approach for research and program design and evaluation. National Institutes for Health. Retrieved from https://obssr-archive.od.nih.gov/pdf/cultural_framework_for_health.pdf

- Kannan, S., Webster, D., Sparks, A., Acker, C. M., Greene-Moton, E., Tropiano, E., & Turner, T. (2009). Using a cultural framework to assess the nutrition influences in relation to birth outcomes among African American women of childbearing age: application of the PEN-3 theoretical model. Health Promotion Practice, 10(3), 349–358. 10.1177/1524839907301406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J., Vesel, L., Bahl, R., & Martines, J. C. (2015). Timing of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding during the first month of life: effects on neonatal mortality and morbidity—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(3), 468–479. 10.1007/s10995-014-1526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide to applied research (5th. ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kull, I., Melen, E., Alm, J., Hallberg, J., Svartengren, M., van Hage, M., et al. Bergström, A. (2010). Breast-feeding in relation to asthma, lung function, and sensitization in young schoolchildren. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 125(5), 1013–1019. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutenbacher, M., Karp, S. M., & Moore, E. R. (2016). Reflections of black women who choose to breastfeed: influences, challenges and supports. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(2), 231–239. 10.1007/s10995-015-1822-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack, N., Woodsong, C., MacQueen, K. M., Guest, G., & Namey, E. (2005). Qualitative research methods. Research Triangle Park, NC: A data collector’s field guide ; Family Health International; http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/Qualitative%20Research%20Methods%20-%20A%20Data%20Collector's%20Field%20Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mattox, K. K. (2012). African American mothers: bringing the case for breastfeeding home. Breastfeeding Medicine, 7(5), 343–345. 10.1089/bfm.2012.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickens, A. D., Modeste, N., Montgomery, S., & Taylor, M. (2009). Peer support and breastfeeding intentions among black WIC participants. Journal of Human Lactation, 25(2), 157–162. 10.1177/0890334409332438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mojab, C. G. (2006). Regarding the emerging field of lactational psychology. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 22(1), 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D., & Krueger, R. (1998). The focus group kit (Vols. 1–6). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M., & Field, P. A. (1995). Qualitative research methods for professionals. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard, M. A., Olesen, F., Andersen, R. S., & Sondergaard, J. (2009). Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 52 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbuanu, C. A., Probst, J., Laditka, S. B., Liu, J., Baek, J., & Glover, S. (2009). Reasons why women do not initiate breastfeeding: A southeastern state study. Women's Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, 19(4), 268–278. 10.1016/j.whi.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, E., & Woods-Giscombé, C. (2015). Infant-feedingpractices among African American women: Social-ecological analysis and implicationsfor practice. Journal of TransculturalNursing, 26(3), 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley, E. B. (2006). A review of paying research participants: It's time to move beyond the ethical debate. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 1(4), 9–19. 10.1525/jer.2006.1.4.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2014). Buiding a culture of health: 2014 president's message. Retrieved from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/annual-reports/presidents-message-2014.html

- Roulston, K. (2010). Reflective interviewing: A guide to theory and practice. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (1993). Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. Advances in Nursing Science, 16(2), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (1994). Focus on qualitative methods. Notes on transcription. Research in Nursing and Health, 17(4), 311–314. 10.1002/nur.4770170410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health, 33(1), 77–84. 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, B., Wambach, K., & Domain, E. W. (2015). African American women's breastfeeding experiences: cultural, personal, and political voices. Qualitative Health Research, 25(7), 974–987. 10.1177/1049732314554097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. Y. (2009). Recruitment of three generations of African American women into genetics research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(2), 219–226. 10.1177/1043659608330352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V. G. (2004). The psychology of black women: Studying women’s lives in context. Journal of Black Psychology, 30(3), 286–306. 10.1177/0095798404266044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2011). The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2012). Healthy people 2020. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. (2015). Infant mortality and African Americans. Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23

- Victora, C. G., Bahl, R., Barros, A. J., França, G. V., Horton, S., Krasevec, J., et al. Rollins, N. C, G. V., Horton.., & Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387(10017), 475–490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. M., Merriwether, A., & Caruthers, A. (2006). Breasts are for men: Media, masculinity ideologies, and men’s beliefs about women’s bodies. Sex Roles, 106(3), 703–714. 10.1007/s11199-006-9125-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J. L., Webb, L., & Levy, M. (2014). Barriers to breastfeeding in the African American population of Shelby County, Tennessee. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(8), 385–392. 10.1089/bfm.2014.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, D. G. (1999). Ar'n't I a woman? Female slaves in the plantation South. New York, NY: Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé, C. L., & Woods-Giscombé, C. L. (2015). Infant-feeding practices among African American women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26(3), 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2013). Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. The American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1157–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]