Abstract

Alveolar soft-part sarcomas are clinically and morphologically distinct soft-tissue sarcomas, with an unknown histogenesis. When the tumors affect the region of the head and neck, they are often located in the orbit and tongue. We report a case of an alveolar soft-part sarcoma in the left masseter of a 28-year-old female. The patient had chronic pain and paresthesia of her left lower lip. Panoramic radiography and computed tomography showed a well-delimited radiolucent mass in the left ramus. An incisional biopsy was performed, and the sample submitted for histopathological study. The tumor showed positive periodic acid-Schiff diastase-resistant granules. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for myoglobin, and focally positive for actin and desmin.

Keywords: alveolar soft-part sarcoma (ASPS), oral cancer, oral sarcoma

Introduction

Alveolar soft-part sarcomas (ASPSs) are clinically and morphologically distinct soft-tissue sarcomas first defined and named by Christopherson et al in 1952.1 ASPSs are rare, uniform malignant neoplasms with no benign counterpart that account for <1% of all soft-tissue sarcomas.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Tumors are usually associated with muscle, but the histogenesis remains uncertain.2, 3, 8 Most of the tumors occur in adolescents and young adults (age 15–30 years), and females are more often affected.5, 8 There are two main locations of these tumors. In adults, they are seen predominantly in the lower extremities. In infants and children (27%), tumors are often located in the region of the head and neck, especially the orbit and tongue.1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 ASPSs usually present as slowly growing, painless masses that almost never cause functional impairment. Because of the relative lack of symptoms, they are easily overlooked. In a number of cases, metastasis to the lung or brain is the first manifestation of the disease.1

We present a case of a 28-year-old female, suffering an apparent toothache, who presented with ASPS of the masseter and left mandibular ramus, and review the literature of the past 10 years.

Case report

A 28-year-old female was referred to the Department of Oral Pathology and Surgery of Andres Bello University, for evaluation of chronic pain of her left mandible and paresthesia of her left lower lip, within a period of 2 months, in which her general practitioner performed a root canal on tooth 3.7. In the intraoral examination, no problems in the mouth opening or oral mucosa, and no tooth alterations were seen. Upon palpation, the patient presented an ill-defined 3-cm-long painful mass that arose from her left ramus, and was covered by the normal mucosa. A panoramic radiograph showed a well-delimited radiolucent mass in the left ramus with effacement of the mandibular channel (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed that the lesion was destroying the entire ramus and infiltrating the masseter (Fig. 2). A malignant lesion, osteosarcoma like, was suggested by the Imagenology Department of the Naval Hospital. An incisional biopsy under local anesthesia was performed. During this procedure, abundant hemorrhage and pain refractory to a local anesthetic were observed.

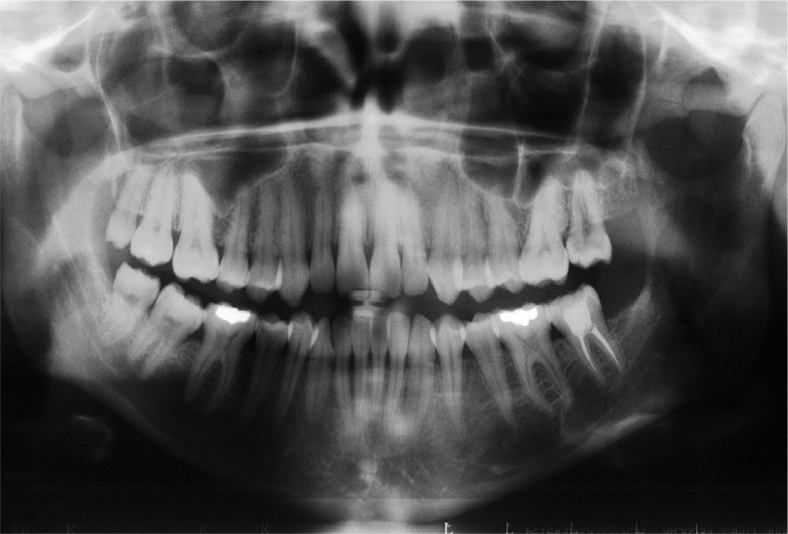

Figure 1.

Panoramic radiograph showing a well-defined radiolucency in the left mandibular ramus.

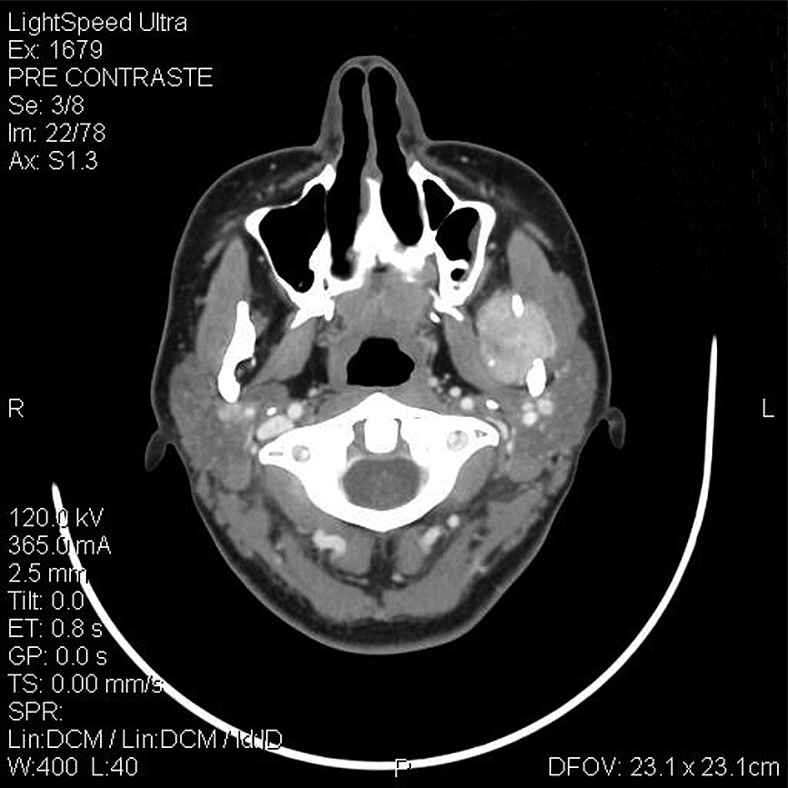

Figure 2.

Axial computed tomography scan of the patient showing a well-circumscribed mass involving the left masseter and mandibular ramus.

Pathology

Several irregular and soft-tissue sections of the lesion were sent to the Oral Pathology laboratory of Andres Bello University, with a presumptive diagnosis of an oral sarcoma.

A microscopic study using routine techniques with hematoxylin and eosin showed proliferation of large polygonal cells separated by thin fibrous septa and numerous vascular channels disposed in a lobular arrangement. The nuclei were round and disposed centrally, and few and normal mitoses were seen. Cells contained abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3).

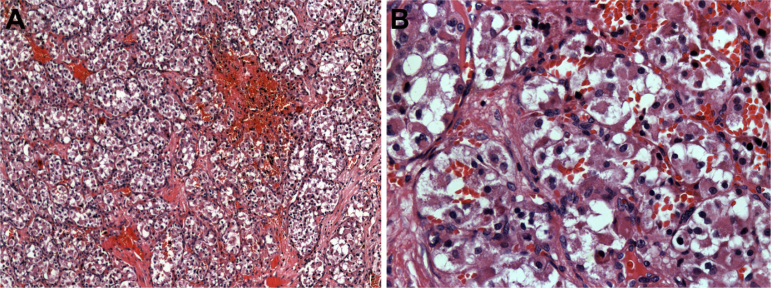

Figure 3.

(A) Histopathological features of the sample with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Nests of neoplastic cells are separated by fibrovascular tissue. Note the pseudoalveolar pattern of the lesion (×10). (B) Histopathological features of the sample with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Cells present irregular borders with abundant granular cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (×40).

The patient was sent to the Renal Pathology Department to rule out the possibility of a clear cell metastatic carcinoma of the kidney. Echography of the kidney was taken, and no changes were observed.

The periodic acid-Schiff technique was used, and positive diastase-resistant granules were focally seen. On immunohistochemistry (IHC), tumor cells were diffusely positive for myoglobin, focally positive for actin and desmin (Fig. 4), and negative for cytokeratin, S-100, and chromogranin.

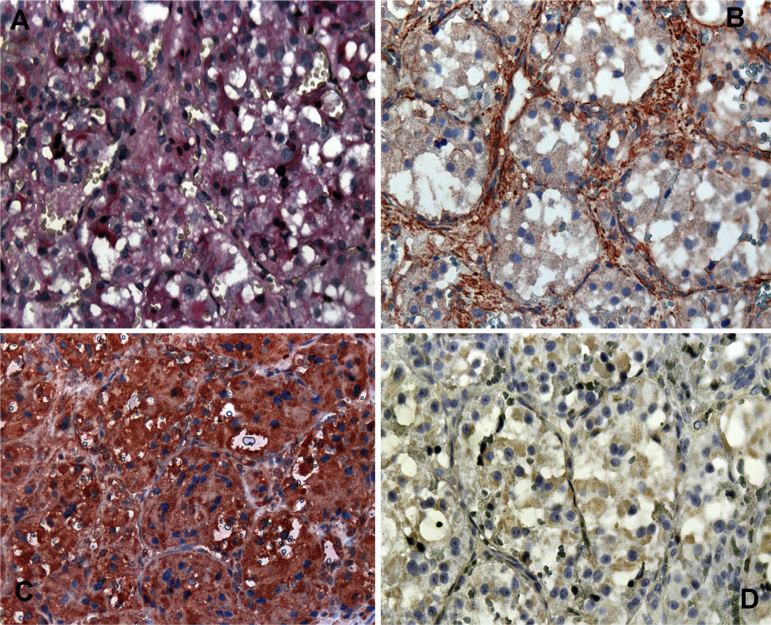

Figure 4.

(A) Histochemical study of the sample. Periodic acid-Schiff-positive diastase-resistant granules (×40). (B) Immunohistochemical staining with anti-actin with a focally positive reaction (×40). (C) Immunohistochemistry revealing a diffuse positive anti-myoglobin reaction (×40). (D) Immunohistochemical features of the sample with a focally positive anti-desmin reaction (×40).

Samples were discussed with two general pathologists of the main hospitals of the region, and both agreed with our diagnosis of ASPS.

Treatment and follow-up

The patient was referred to the Oncology Department of a local hospital, where complete excision of the lesion and a partial hemimandibulectomy were performed. The histopathological findings were similar to those of the previous biopsy, and the diagnosis of ASPS was corroborated. One lymph node was examined, but no tumor-cell infiltration was observed. A complete CT scan was performed, and no metastases were seen. Additional radiotherapy was given, because there was a microscopic positive margin. The orientations of the edges were impossible to locate due to the irregularity of the tumor. Up to 66 Gy of radiation therapy was given in a period of 2 months. The patient was examined 1 month and 6 months after finishing radiation therapy, and no signs of recurrence or metastases were seen. One year later, the patient complained of multiple lesions on the scalp, of 3 cm in diameter. A biopsy was taken, and a diagnosis of metastatic ASPS was confirmed. A new CT scan revealed metastatic lesions in the right parietal bone and lungs. No lesions were seen in the primary site of the tumor, so the scalp lesions were considered metastases rather than the local extension of the primary lesion.

Discussion

ASPSs are rare malignant tumors of uncertain type with a peak incidence at age 15–35 years with oral cases typically occurring in childhood. There is a female preponderance prior to age 30 years.2, 9 Our patient was a 28-year-old female, and the tumor was located in her left masseter and had invaded her left mandibular ramus. This is an unusual location for this tumor in an adult, considering previous reports, that the principal location of ASPSs in adults is the extremities, and when affecting the oral region, the tongue is most frequently involved, followed by the cheek (Table 1). There is only one case in the literature, reported by Richards et al,4 that was localized to the mandible. The present case seems to be the first instance of an ASPS located on the masseter with bone invasion.

Table 1.

Review of cases of oral alveolar soft part sarcoma of the past 10 years.

| Study | Age (years) | Gender | Site | Symptoms | PAS diastase-resistant intracytoplasmic granules | IHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noussios et al (2010)11 | 3 | M | Tongue | Painful mass | Positive | — |

| Eley et al (2010)9 | 24 | M | Tongue | Soft fluctuant swelling; asymptomatic | Positive | MyoD1 (+) |

| Wakely et al (2009)17 | 8 | F | Oral cavity | NR | NR | NR |

| Tapisiz et al (2008)12 | 18 | F | Tongue | Swelling, pain | NR | NR |

| Correia-Silva et al (2006)13 | 17 | F | Tongue | Nodule at the dorsum surface of the tongue; asymptomatic | MSA(+) Myo D1 (+) Myogenin (+) Desmin (+) NSE (+) S100 (−) CK-AE1-AE3 (−) Vimentin (−) |

|

| Souza et al (2005)5 | 13 | F | Tongue | Painless, erythematous nontender nodule | Positive | NSE (+) Vimentin (+) Desmin (+) S100 (+) CK–AE1–AE3 (+) EMA (+) Neurofilament (+) MSA(+) |

| Kanhere et al (2005)14 | Mean 27, | 1 F | Tongue | Slow-growing mass; firm in consistency | Positive | NSE (−) CK (−) Vimentin (−) |

| range 6–43 | 3 M | |||||

| Kim et al (2005)15 | 16 4 22 |

M F M |

Tongue Tongue Cheek |

Painless swelling | Positive | Cytokeratin (−) |

| Fanburg-Smith et al (2004)16 | Mean 8, range 3–21 |

5 F 7 M |

Tongue | Erythematous mass, pain, dysphagia, and dysphasia | Positive | MSA(+) Desmin (+) S100 (−) CK (−) Vimentin (−) Myo D1 (−) Myogenin (−) Myoglobin (−) |

| Aiken and Stone (2003)7 | 34 | F | Tongue | Oral bleeding, tongue swelling, dysphonia, progressive dysphagia | Positive | S 100 (−) |

| Richards et al (2003)4 | 16 | M | Mandible | Painless and progressive enlargement of the right mandibular angle | Positive | Vimentin (+) NSE (+) |

| Charrier et al (2001)10 | 54 | F | Cheek | Large swelling, severe pain, trismus | Negative | Desmin (+) Vimentin (+) S100 (−) CK (–) |

| Yoshida et al (2000)6 | 2 | F | Tongue | Painless mass | Positive | MyoD1 (+) Myoglobin (+) NSE (+) |

| Kimi et al (2000)2 | 25 | F | Cheek | Painless | Positive | Anti–myoglobin (+) NSE (+) Sarcomeric actin (+) |

CK = cytokeratin; EMA = human epithelial membrane antigen; F = female; IHC = immunohistochemistry; M = male; MSA = muscle-specific-actin; NR = not reported; NSE = neuron-specific enolase; PAS = periodic acid-Schiff.

Some clinical signs and symptoms of this patient were also considered unusual. Despite the size of the tumor (>5 cm), there was no clinical mass and no facial deformity, which according to the literature should be a common sign (Table 1).4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 It is also uncommon, only reported by Charrier et al,10 that the tumor was very painful, and this is the first reported case with paresthesia of the lower lip.

As a rule, the tumor is richly vascularized. Massive hemorrhaging may be encountered during surgical removal.1, 17 In rare instances, there is erosion or destruction of the underlying bone, reported only by Weiss,1 which was remarkable in our case.

The microscopic picture varies little from tumor to tumor, and this uniformity is one of its characteristic features.1, 3, 17 Differential diagnoses of ASPSs include tumors with large cells organized in nests with eosinophilic/clear cytoplasm, such as renal clear cell carcinomas, malignant melanomas, adrenal cortical carcinomas, hepatocellular carcinomas, and paragangliomas. However, all of the differential diagnoses can be excluded with adequate periodic acid-Schiff and IHC analyses.3, 8

IHC analysis often leads to variable results, and there is no consensus on antigen reactivity (Table 1). The myogenic theory of origin seems to be the most accepted to date.4, 6 This theory is based in positive reactions to IHC muscle markers, such as actin, desmin, MyoD1, and myogenin. Another suggestion is that the tumor represents a neural crest derivative, because many cells exhibit S-100 and neuron-specific enolase positivity.4, 5 In our case, tumor cells were diffusely positive for myoglobin, focally positive for actin and desmin, and negative for cytokeratin, S-100, and chromogranin, which supports the myogenic theory of tumor origin.

Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment.4, 9 Radiotherapy has been added as a surgical adjunct with varying success rates. It is recommended for microscopic residual disease, positive surgical margins, and palliation for metastases.4 Five-year survival is approximately 59–70% after surgical resection but decreases dramatically to only 15% for the 20-year follow-up.4, 7 Twenty percent of patients will develop distant metastasis more than 10 years after the initial surgical resection; consistent and long-term follow-up is therefore critical for those affected by ASPS.4

In conclusion, this case highlights the aggressiveness of ASPSs, and the potential to develop metastases. Hence, close clinical follow-up is absolutely necessary. It is important to note that when a patient complains of pain and paresthesia, the first thing to do is to discount the presence of cancer or osteomyelitis, and the examination should begin with a panoramic radiograph.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Raul Gonzalez for assistance with the immunohistochemical study.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

References

- 1.Weiss S.W., Goldblum J.R., editors. Soft Tissue Tumors, Chapter 37, Malignant Soft Tissue Tumors of Uncertain Type. Mosby; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 1182–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimi K., Onodera K., Kumamoto H., Ichinohasama R., Echigo S., Ooya K. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the cheek: report of a case with a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silbergleit R., Agrawal R., Savera A.T., Patel S.C. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the neck. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:861–863. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards S.V., Welch D.C., Burkey B.B., Bayles S.W. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the mandible. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:148–150. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.do Nascimento Souza K.C., Faria P.R., Costa I.M., Duriguetto A.F., Jr., Loyola A.M. Oral alveolar soft-part sarcoma: review of literature and case report with immunohistochemistry study for prognostic markers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K., Kurauchi J., Shirasawa H., Kosugi I. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the tongue. Report of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:370–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken A.H., Stone J.A. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the tongue. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1156–1158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocha L.A., Rizo V.H., Romañach M.J., de Almeida O.P., Vargas P.A. Oral metastasis of alveolar soft-part sarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eley K.A., Afzal T., Shah K.A., Watt-Smith S.R. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the tongue: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:824–826. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charrier J.B., Esnault O., Brette M.D., Monteil J.P. Alveolar softpart sarcoma of the cheek. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:394–397. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noussios G., Chouridis P., Petropoulos I., Karagiannidis K., Kontzoglou G. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the tongue in a 3-year-old boy: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:130. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapisiz O.L., Gungor T., Ustunyurt E., Ozdel B., Bilge U., Mollamahmutoglu L. An unusual case of lingual alveolar soft part sarcoma during pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;2:212–214. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correia-Silva J.F., Duarte E.C.B., Lacerda J.C.T., Sousa S.C.O.M., Mesquita R.A., Gomez R.S. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the tongue. Oral Oncology EXTRA. 2006;42:241–243. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanhere H.A., Pai P.S., Neeli S.I., Kantharia R., Saoji R.R., D'Cruz A.K. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of the head and neck. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H.S., Lee H.K., Weon Y.C., Kim H.J. Alveolar soft-part sarcoma of the head and neck: clinical and imaging features in five cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1331–1335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanburg-Smith J.C., Miettinen M., Folpe A.L., Weiss S.W., Childers E.L.B. Lingual alveolar soft part sarcoma; 14 cases: novel clinical and morphological observations. Histopathology. 2004;45:526–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakely P.E., Jr., McDermott J.E., Ali S.Z. Cytopathology of alveolar soft part sarcoma: a report of 10 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2009;117:500–507. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]