Abstract

Background/purpose

Presence of pulp stones increase the difficulty of locating canal orifice during endodontic treatment. This study aims to determine the prevalence of pulp stones in a northern Taiwanese population through analysis of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Materials and methods

A total of 144 patients and 2554 teeth were used in the present study which were collected from a CBCT image archive. To determine the presence of pulp stones, images of pulp chamber and root canals were analyzed in the sagittal, axial and coronal planes and from the occlusal to apical direction. Correlations between pulp stones and gender, age, tooth type, dental arch or side were also examined.

Results

Of the 144 patients, 120 patients (83.3%) and 800 (31.3%) teeth were found to have one or more pulp stones through CBCT examination. Prevalence of pulp stones between dental arches and tooth types were significantly different (P < 0.001). Pulp stones were found to be the most prevalent in first molars (50.0%) and most scarce in first premolars (18.8%). There was no significant correlation between pulp stones and gender, increasing age, or dental sides.

Conclusion

Pulp stones are more frequent in maxillary teeth compared to mandibular teeth. Pulp stones in molar teeth were significantly more common than premolars and incisors. CBCT could be a sensitive tool to detect pulp stones, especially simplifying identification of pulp stones in radicular pulp. Knowledge of pulp stones distribution can aid dentists in clinical endodontic treatment.

Keywords: cone-beam computed tomography, pulp calcification, pulp stones

Introduction

Successful endodontic treatment hinges on the ability to accurately locate, clean, shape, and obturate the three-dimensional root canal system.1 Pulp calcification presents difficulties in endodontic treatment: canal orifices may be obscured which increases the difficulty of pulp chamber access and the risk of instrument breakage.

Calcified structures are fairly common in human dental pulps. The two main morphological forms of pulp calcifications are discrete pulp stones (denticles or pulp nodules) and diffuse calcifications.2 Pulp stones tend to present themselves more coronally as discrete and concentric calcifications, while radicular calcifications are more rare and exist more diffusely.3 Pulp stones may be embedded, attached to dentin walls, or occur freely within the pulp tissue.4, 5 They are found in both deciduous and permanent teeth.6 The exact etiology of pulp stone formation remains unclear,5 However, several factors that have been implicated in stone formation, including: pulp calcification, aging, orthodontic tooth movement, periodontal disease, various systemic diseases, genetic predisposition, bacterial infection, deep caries, and restorations.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Previous studies have reached no consensus regarding prevalence of pulp stones and reported results range from 8% to 90%.14 Sizes of pulp stones vary from minute particles to masses large enough to obliterate the pulp chamber.7 In clinical practice, pulp stones can be identified in periapical and bite-wing radiographs. However, pulp stones smaller than 200 μm in diameter are undetectable in these radiographs, therefore actual incidences may be higher.15

Conventional radiographs produce only 2-dimensional images of 3-dimensional objects, resulting in the distortion and superposition of anatomic structures such as the zygomatic arch, the floor of maxillary sinus, and obscure root canal anatomy.16 Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans are becoming more common in clinical practice and have been found to be useful in providing accurate three dimensional anatomic details suitable for diagnosis and treatment planning before endodontic therapy.17 Furthermore, CBCT was reported to be a sensitive diagnostic method to identify stones compared to digital radiography.18 Previous studies showed a wide discrepancy in the prevalence of pulp stones in different populations. These variations in prevalence between different populations may be due to ethnic and geographical differences.19, 20 Two recent studies in Brazil used CBCTs for this and revealed the prevalence of pulp stones in people were 55% and 31.9%, respectively.21, 22 However, no study has investigated the prevalence of pulp stones in the Taiwanese population. Therefore, the aims of this study was to determine the prevalence of pulp stones in the Taiwanese population through CBCT analysis and find any connections between pulp stones with gender, age, tooth type, dental side and dental arch.

Materials and methods

Image acquisition and confidentiality

All qualified participants in this study were Taiwanese patients from the Department of Dentistry, Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. The project and protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center (TSGHIRB No. 2-105-05-07). All images were acquired with a CBCT machine (NewTom 5G; QR, Verona, Italy) between January 2012 and December 2013, and were not taken with specific intent to be used in this study. Board-certified radiologists operated the X-ray tube at an accelerated potential of 110 kV peak, with a beam current of 11.94 mA, and automatically adjusted the exposure time according to the area of scanning (about 7 s for a full arch). The field of view was fixed at 30.5 cm2 × 20.3 cm2 and the resolution and separation of each slice was 0.15 mm. The CBCT scans were saved in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format and encrypted. CBCT images of 199 patients were initially examined but only 144 patients' images qualified for further analysis based on the following inclusion criteria:

The inclusion and exclusion criteria was adapted from previous studies with some modification.19, 21, 22, 23

-

1.

Each subject has at least one fully erupted permanent tooth.

-

2.

Each investigated tooth has the apex fully formed.

-

3.

Radiopaque masses in the pulp chamber or root were diagnosed as pulp stones.

Exclusion criteria of images

-

1.

Teeth have either: mid root canal treatment, have undergone root canal treatment or have crowns or posts inserted.

-

2.

Unclear or incomplete image due to scattering, or beam-hardening artifact.

-

3.

Deep carious lesion or restorations that invaded pulp chambers which interfere with the reading of images.

-

4.

Third molars

Morphologic analysis

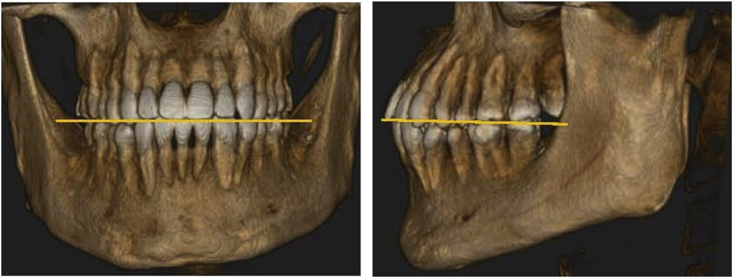

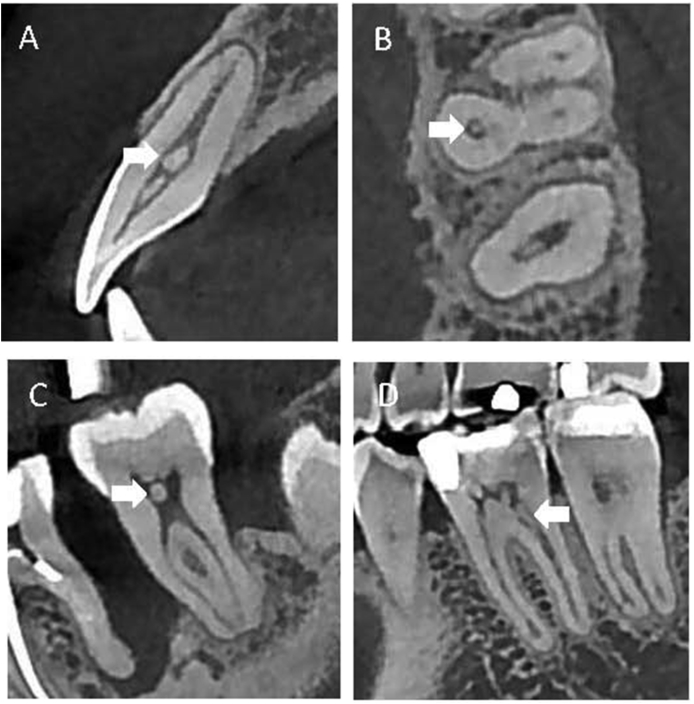

Qualified images of patients were analyzed in detail using ImplantMax software (HiAim Biomedical Technology, Taipei, Taiwan). The images were re-oriented so that the maxilla was bilaterally symmetric, and the occlusal plane, either in frontal or sagittal view, was parallel to the ground (Fig. 1). A series of images of teeth were analyzed in sagittal, axial, and coronal views of both pulp chambers and root canals, in a coronal to apical direction, to detect presence of pulp stones (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic description of the image orientation procedure. Skull orientation and regions of interest from frontal and lateral views.

Figure 2.

Pulp stones detected by CBCT scan in different views. (A) A free pulp stone in right maxillary incisor, sagittal view. (B) A free pulp stone in the palatal root of left maxillary first molar, axial view. (C) A free pulp stone in the pulp chamber of left second mandibular molar, sagittal view. (D) A pulp stone in the distal root of first mandibular molar, sagittal view.

Data acquisition and validation

All images were displayed on a 19-inch LCD monitor (ChiMei, Innolux Corporation, Tainan, Taiwan) with a 1920 × 1080 pixel resolution. To assess data reliability, all images were re-positioned and examined in a dimly lit environment by two calibrated examiners (C.-C. Hsieh, and Y.-C. Wu). An intra-examiner and inter-examiner calibration was performed for nominal variables to assess data reliability based on the anatomic diagnosis of CBCT images by evaluation of 50 randomly selected images. The kappa analysis was performed before the disagreements among examiners were discussed and resolved. The kappa statistic values for nominal variables were 0.932 and 0.926 for intra-, and inter-observer agreement, respectively. After calibration, the two examiners separately evaluated the images, and any disagreement in the interpretation of images was discussed until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequencies and percentages at patient and tooth levels. Proportion of pulp stones among subgroups (i.e., dental arch, side, tooth type) was compared using Fisher's exact test. To investigate the independent effect on the risk of pulp stones, we performed a multivariable logistic model with generalized estimating equation (GEE) in which we introduced the effects of dental arch, side, and tooth type simultaneously. In contrast to the traditional statistical method (such as conventional logistic regression analysis) which treats teeth from a subject as if they were teeth from different subjects, the GEE can account for the outcome dependency of multiple teeth of an individual patient. We performed the data analyses by SPSS 22 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Of the 144 patients, 120 patients (83.3%) were found to have one or more pulp stones in our CBCT examination. In general, pulp stones were significantly higher in males than females (90.6% vs. 72.9%, P = 0.006). Although not statistically different, patient age was divided into four groups and the results showed the prevalence of pulp stones to be highest among 20–39 years (86.8%), followed by ≥ 60 years (85.3%), <20 years (83.3%), and 40–59 years (80.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of examined teeth with pulp stones by patient's characteristics.

| Variable | No. of patient examined | Patient with pulp stones, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.006 | ||

| Male | 85 | 77 (90.6) | |

| Female | 59 | 43 (72.9) | |

| Age, years | 0.824 | ||

| <20 | 6 | 5 (83.3) | |

| 20–39 | 38 | 33 (86.8) | |

| 40–59 | 66 | 53 (80.3) | |

| ≥60 | 34 | 29 (85.3) | |

| Total number of patient | 144 | 120 (83.3) | — |

In the examined 2554 teeth using CBCT, there were 800 (31.3%) teeth with pulp stones. Prevalence of pulp stones between dental arches was significantly different (P < 0.001) in which the maxilla reported 36.4% and the mandible 26.6%. The prevalence of pulp stones were similar between right- and left-sided teeth (32.2% vs. 30.4%, P = 0.327). The prevalence of pulp stones among tooth types were also substantially different (P < 0.001): pulp stones occurred most frequently in the first molar (50.0%), followed by the second molar (46.2%), and lastly the second premolar (19.1%) and first premolar (18.8%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of examined teeth with pulp stones by teeth characteristics.

| Variable | No. of teeth examined | Teeth with pulp stones, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental arch | <0.001 | ||

| Maxilla | 1224 | 446 (36.4) | |

| Mandible | 1330 | 354 (26.6) | |

| Side | 0.327 | ||

| Right | 1272 | 410 (32.2) | |

| Left | 1282 | 390 (30.4) | |

| Tooth type | <0.001 | ||

| Incisor | 409 | 119 (29.1) | |

| Lateral incisor | 432 | 127 (29.4) | |

| Canine | 464 | 161 (34.7) | |

| First premolar | 384 | 72 (18.8) | |

| Second premolar | 325 | 62 (19.1) | |

| First molar | 252 | 126 (50.0) | |

| Second molar | 288 | 133 (46.2) | |

| Total number of teeth | 2554 | 800 (31.3) | — |

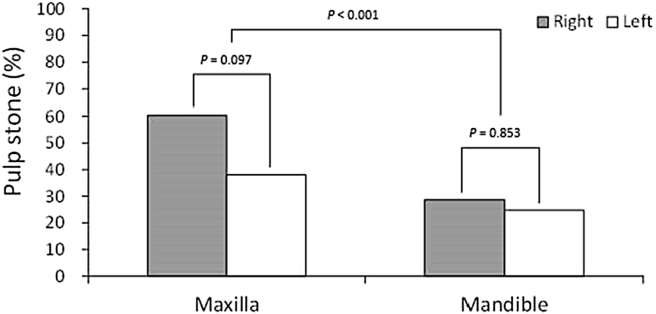

The comparison of pulp stones prevalence between right- and left-sided teeth was not significantly different in the maxilla nor mandible (P = 0.097, 0.083, shown as Fig. 3). Distribution of pulp stones among tooth type was significantly different in both the maxilla and mandible (P < 0.001, both) in which the prevalence was highest in the first molar (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of examined teeth with pulp stones by left or right side in the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Table 3.

Distribution of teeth with pulp stones by examined teeth characteristics in the maxillary and mandibular teeth.

| Variable | Maxilla |

Mandible |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of teeth examined | Teeth with pulp stones, n (%) | P | No. of teeth examined | Teeth with pulp stones, n (%) | P | |

| Side | 0.097 | 0.853 | ||||

| Right | 601 | 233 (38.8) | 671 | 177 (26.4) | ||

| Left | 623 | 213 (34.2) | 659 | 177 (26.9) | ||

| Tooth type | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Incisor | 169 | 73 (43.2) | 240 | 46 (19.2) | ||

| Lateral incisor | 189 | 70 (37.0) | 243 | 57 (23.5) | ||

| Canine | 216 | 79 (36.6) | 248 | 82 (33.1) | ||

| First premolar | 176 | 28 (15.9) | 208 | 44 (21.2) | ||

| Second premolar | 167 | 26 (15.6) | 158 | 36 (22.8) | ||

| First molar | 142 | 82 (57.7) | 110 | 44 (40.0) | ||

| Second molar | 165 | 88 (53.3) | 123 | 45 (36.6) | ||

| Total number of teeth | 1224 | 446 (36.4) | — | 1330 | 354 (26.6) | — |

Outcome dependency of individuals with multiple teeth and the effects of introducing dental arch, side and tooth type into the multivariable GEE logistic model were accounted for simultaneously using generalized estimating equation (GEE). The presence of pulp stones was significantly lower in mandibular teeth than in the maxilla (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.81). Compared to incisors, the presence of pulp stones was significantly lower in the first premolars (aOR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.37–0.75) and second premolars (aOR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.41–0.74) but significantly higher in the first molars (aOR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.66–3.16) and second molars (aOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.39–2.71) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable GEE type logistic regression analysis of associated factors with pulp stones in total examined teeth.

| Variable | aOR | 95% CI of aOR | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental arch | |||

| Maxilla | Ref. | — | — |

| Mandible | 0.66 | 0.54–0.81 | <0.001 |

| Side | |||

| Right | Ref. | — | — |

| Left | 0.94 | 0.81–1.08 | 0.371 |

| Tooth type | |||

| Incisor | Ref. | — | — |

| Lateral Incisor | 1.01 | 0.80–1.28 | 0.907 |

| Canine | 1.25 | 0.95–1.64 | 0.115 |

| First premolar | 0.53 | 0.37–0.75 | <0.001 |

| Second premolar | 0.55 | 0.41–0.74 | <0.001 |

| First molar | 2.29 | 1.66–3.16 | <0.001 |

| Second molar | 1.94 | 1.39–2.71 | <0.001 |

GEE, generalized estimating equation; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Number of teeth = 2554 and number of patient = 144.

Presence of pulp stones was further analyzed separately in maxillary and mandibular teeth. In maxillary teeth, the result demonstrated the prevalence of pulp stones to be significantly lower in first premolar (aOR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.15–0.43) than second premolars (aOR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.16–0.41) and was significantly higher in the first molars (aOR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.28–3.00) compared to incisors. Notably, we found that the risk of pulp stones to be significantly higher in canines (aOR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.41–2.93) than incisors in mandibular teeth (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable GEE type logistic regression analysis of associated factors with pulp stones in examined maxillary and mandibular teeth.

| Variable | Maxilla |

Mandible |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI of aOR | P | aOR | 95% CI of aOR | P | |

| Side | ||||||

| Right | Ref. | — | — | Ref. | — | — |

| Left | 0.84 | 0.68–1.03 | 0.085 | 1.06 | 0.85–1.31 | 0.624 |

| Tooth type | ||||||

| Incisor | Ref. | — | — | Ref. | — | — |

| Lateral Incisor | 0.83 | 0.59–1.17 | 0.286 | 1.31 | 0.92–1.87 | 0.134 |

| Canine | 0.78 | 0.55–1.11 | 0.162 | 2.03 | 1.41–2.93 | <0.001 |

| First premolar | 0.25 | 0.15–0.43 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.70–1.61 | 0.785 |

| Second premolar | 0.26 | 0.16–0.41 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 0.80–1.87 | 0.351 |

| First molar | 1.96 | 1.28–3.00 | 0.002 | 2.75 | 1.79–4.22 | <0.001 |

| Second molar | 1.47 | 0.96–2.28 | 0.080 | 2.41 | 1.53–3.81 | <0.001 |

GEE, generalized estimating equation; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Number of teeth = 1224 and number of patient = 140 in maxillary teeth.

Number of teeth = 1330 and number of patient = 144 in mandibular teeth.

Discussion

This study uses a non-invasive technique to evaluate the prevalence of pulp stones and its associations with gender, age, tooth type, dental arch, and dental side. Previously, most pulp stones studies used conventional radiography or histological examination. In conventional radiographs, the diameter of a calcified structure must exceed 200 μm to be detected, therefore, true prevalence of pulp stones could have been higher.15 Additionally, on periapical and bite-wing radiographs, pulp stones identification may be hindered due to overlapping with alveolar bone. A previous study of pulp calcification in 132 human teeth showed prevalence to be higher in histological surveys than conventional radiographic examination.4 However, this experimental design required teeth extraction, and each tooth underwent limited numbers of sectioning. In the present study, we utilized CBCT examination to detect pulp stones in multiple aspects, thus overcoming the limitation of conventional radiographs and histology examination. The number of clinical practices utilizing CBCT as a diagnostic tool has been growing. CBCT helps dentists to better understand the relationships among teeth, dental arches, and facial skeleton structures in a three dimensional space.24 In root canal treatment, CBCT helps dentists to correctly diagnose and identify the complexity of root canal systems, thus increasing the success rate of non-surgical and surgical root canal retreatments. As CBCT provides high-resolution images in multiple planes of space and eliminates superimposition of surrounding structures, it is a superior method to detect pulp stones compared to conventional radiography.

Using CBCT scans for examination, our study detected the prevalence of pulp stones to be 83.3% in people, and 31.3% in teeth. The prevalence of pulp stones has also been examined in other studies, with varying results ranging from 8% to 90%.14 Possible explanations for the lack of consensus include: First, the prevalence of pulp stones may differ in ethnic and geographical backgrounds.19, 20 For example, Hamasha and Darwazeh reported pulp stones prevalence in radiographs to be 51% in 814 Jordanian adults and 22% in teeth.25 Utilizing bitewing radiographs, Ranjitkar et al. reported pulp stones prevalence of 217 Australian dental students, aged from 17 to 35 years old, to be 46% in people and 10% in teeth.20 Looking at periapical radiographs, Sathya Kannan et al. reported pulp stones prevalence in 361 patients from three races in Malaysia, aged from 10 to 70 years old, to be 44.9% in people and 15.7% in teeth.23 Second, the difference in the methods of examination, such as conventional radiographs, CBCTs, and histological examinations (Table 6). In addition, most studies were detecting pulp stones only in the pulp chamber.20, 23 In the present study, we extended the area of investigation to the root canal space. As a result, the present study has higher prevalence of pulp stones than other studies.

Table 6.

Methods for detecting pulp stones/pulp calcifications in some surveys.

| Investigator | Methodology | Race | Sample | Age of subjects (years) | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sayegh et al.(1968) | Histology | — | 591 teeth | 8–63 | 8-90% of teeth |

| Ary et al.(1993) | Microradiography and light microscopy | — | 42 teeth | 5–13 | 95% |

| Ranjitkar et al.(2002) | Bitewings | Australian | 3296 teeth | 17–35 | 46% of people, 10.1% of teeth |

| Colak (2012) | Bitewings | Turkish | 2391 teeth | 15–65 | 63.6% of people, 27.8% of teeth |

| Kannan et al.(2015) | Periapical film | Malaysians | 1779 teeth | 10–70 | 44.9% of people, 15.7% of teeth |

| Hillmann & Geurtsen (1997) | Histology | — | 332 teeth | 10–72 | 11–30 years:14.9% of teeth 31–51 years: 44.4% of teeth 52–72 years: 65.1% of teeth |

| Rodrigues et al.(2014) | CBCT | Brazilian | 181 patients | 10–76 | 55% of people (31–40 years: 89.7%) |

| da Silva et al.(2016) | CBCT | Brazilian | 2833 teeth | 19–75 | 31.9% of people, 9.5% of teeth |

| Hsieh et al.(2017) | CBCT | Taiwanese | 2554 teeth | 13–86 | 83.3% of people, 31.3% of teeth |

The incidence of pulp stones was found to be greater in males than females, this result is in accordance with previous studies.25 Possible explanations for different of pulp stones prevalence in genders include: the theory that pulp calcifications are related to pulpal inflammation resulting from chronic, local irritants such as attrition and the effect of tooth wear, which are found more commonly in men.26 Another possibility may be related to the fact that more than 90% of people aged 35–44 years have periodontal disease in Taiwan, more of which were male,27 and previous studies revealed a correlation between periodontal disease and pulp calcification.28, 29 Interestingly, pulp stones are reported to increase in frequency with age.30 However, in our study, the prevalence of pulp stones is not associated with age (Table 1). These contradictory findings may be explained by marked differences in sample size and the methods used. We also noted the occurrence of pulp stones to be significantly higher in the maxillary than mandibular teeth (Table 2). Other studies have demonstrated the prevalence of pulp stones in maxillary and mandibular teeth to be the same.3, 31 There are also studies showing a higher occurrence of pulp stones in mandibular teeth.7, 32 Therefore, further investigation with a larger sample size is required.

In the present study, a higher occurrence of pulp stones was observed in the first molar tooth of both arches, which is in agreement with findings from other studies7, 20, 25, 33 (Table 3). A possible explanation is the size of molars; larger teeth possess superior blood supply, therefore pulp tissue calcifies easier than in smaller teeth. Likewise, the earlier eruption time of molars compared to premolars translates to longer exposure to degeneration or irritants.30 This finding is similar to previous studies.23 On the other hand, pulp stone occurred significantly more often in canines compared to mandible central incisors. (OR = 2.03, P < 0.001) (Table 5). This result is also in accordance to previous studies.23 However, these findings require further investigation, to which we suggest a larger sample size of molars in order to further evaluate pulp stones formation in compromised teeth, such as carious and restored teeth and in teeth of patients with periodontal disease or cardiovascular disease.

In conclusion, maxillary teeth have higher prevalence of pulp stones than mandibular teeth. Pulp stones in molar teeth were significantly more common than premolars and incisors. CBCT could be a sensitive tool to detect pulp stones, especially simplifying identification of pulp stones in radicular pulp. In clinical scenarios, dentists can be more aware of the prevalence of pulp stones which can aid in endodontic treatment.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C (Grant No. TSGH-C105-158, C105-030 and C105-160).

References

- 1.Hammad M., Qualtrough A., Silikas N. Evaluation of root canal obturation: a three-dimensional in vitro study. J Endod. 2009;35:541–544. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kansu O., Ozbek M., Avcu N., Aslan U., Kansu H., Genctoy G. Can dental pulp calcification serve as a diagnostic marker for carotid artery calcification in patients with renal diseases? Dento Maxillo Facial Radiol. 2009;38:542–545. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/13231798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arys A., Philippart C., Dourov N. Microradiography and light microscopy of mineralization in the pulp of undemineralized human primary molars. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevelander G., Johnson P.L. Histogenesis and histochemistry of pulpal calcification. J Dent Res. 1956;35:714–722. doi: 10.1177/00220345560350050901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goga R., Chandler N.P., Oginni A.O. Pulp stones: a review. Int Endod J. 2008;41:457–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaacob H.B., Hamid J.A. Pulpal calcifications in primary teeth: a light microscope study. J Pedod. 1986;10:254–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baghdady V.S., Ghose L.J., Nahoom H.Y. Prevalence of pulp stones in a teenage Iraqi group. J Endod. 1988;14:309–311. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siskos G.J., Georgopoulou M. Unusual case of general pulp calcification (pulp stones) in a young Greek girl. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6:282–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1990.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenvik A., Mjor I.A. Epithelial remnants and denticle formation in the human dental pulp. Acta Odontol Scand. 1970;28:72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edds A.C., Walden J.E., Scheetz J.P., Goldsmith L.J., Drisko C.L., Eleazer P.D. Pilot study of correlation of pulp stones with cardiovascular disease. J Endod. 2005;31:504–506. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000168890.42903.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanDenBerghe J.M., Panther B., Gound T.G. Pulp stones throughout the dentition of monozygotic twins: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:749–751. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng J.F., Zhang W., Jiang H.W., Ling J.Q. Isolation, cultivation and initial identification of Nanobacteria from dental pulp stone. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;41:498–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundell J.R., Stanley H.R., White C.L. The relationship of coronal pulp stone formation to experimental operative procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:579–589. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayegh F.S., Reed A.J. Calcification in the dental pulp. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:873–882. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss-Salentijn L., Hendricks-Klyvert M. Calcified structures in human dental pulps. J Endod. 1988;14:184–189. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen E., Taschieri S., Del Fabbro M., Beitlitum I., Tsesis I. The diagnostic efficacy of cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics: a systematic review and analysis by a hierarchical model of efficacy. J Endod. 2015;41:1008–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel S., Durack C., Abella F., Shemesh H., Roig M., Lemberg K. Cone beam computed tomography in endodontics - a review. Int Endod J. 2015;48:3–15. doi: 10.1111/iej.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lari S.S., Shokri A., Hosseinipanah S.M., Rostami S., Sabounchi S.S. Comparative Sensitivity assessment of cone beam computed tomography and digital radiography for detecting foreign bodies. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:224–229. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colak H., Celebi A.A., Hamidi M.M., Bayraktar Y., Colak T., Uzgur R. Assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in a sample of Turkish central Anatolian population. Sci J. 2012;2012:804278. doi: 10.1100/2012/804278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranjitkar S., Taylor J.A., Townsend G.C. A radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in Australians. Aust Dent J. 2002;47:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Silva E.J., Prado M.C., Queiroz P.M. Assessing pulp stones by cone-beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Investig. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-2027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodrigues V.S.I., Schacht Junior C.F., Bortolotto M., Manhães Junior L.R., Tomazinho L.F., Boschini S. Prevalence of pulp stones in cone beam computed tomography. Dent Press Ebdod. 2014;4:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannan S., Kannepady S.K., Muthu K., Jeevan M.B., Thapasum A. Radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in Malaysians. J Endod. 2015;41:333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S., Dawood A., Ford T.P., Whaites E. The potential applications of cone beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems. Int Endod J. 2007;40:818–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.al-Hadi Hamasha A., Darwazeh A. Prevalence of pulp stones in Jordanian adults. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:730–732. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunha-Cruz J., Pashova H., Packard J., Zhou L., Hilton T.J. Tooth wear: prevalence and associated factors in general practice patients. Community Dent oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:228–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan C.L., You H.J., Lian H.J., Huang C.H. Patients receiving comprehensive periodontal treatment have better clinical outcomes than patients receiving conventional periodontal treatment. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rathod S., Fande P., Sarda T. The effect of chronic periodontitis on dental pulp: a clinical and histopathological study. J Int Clin Dent Res Organ. 2014;6:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubach W.C., Mitchell D.F. Periodontal disease, accessory canals and pulp pathosis. J Periodontol. 1965;36:34–38. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamse A., Kaffe I., Littner M.M., Shani R. Statistical evaluation of radiologic survey of pulp stones. J Endod. 1982;8:455–458. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(82)80150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss-Salentijn L., Klyvert M.H. Epithelially induced denticles in the pulps of recently erupted, noncarious human premolars. J Endod. 1983;9:554–560. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(83)80060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elvery M.W., Savage N.W., Wood W.B. Radiographic study of the broadbeach aboriginal dentition. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;107:211–219. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199810)107:2<211::AID-AJPA7>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulsahi A., Cebeci A.I., Ozden S. A radiographic assessment of the prevalence of pulp stones in a group of Turkish dental patients. Int Endod J. 2009;42:735–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]