Abstract

Background/Purpose

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a common chronic inflammatory disease characterized by a T cell-mediated immune response against epithelial cells. The epidemiological survey of OLP in Taiwanese population was scarce. In this study, we investigated the time trend of prevalence stratified by gender, age, urbanization, and income of OLP based on National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

Materials and methods

We studied the claims data of Taiwanese population from NHIRD 1996 to 2013. Patients with the diagnosis of OLP based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code: 697.0 were recruited in this study. Demographic characteristics were analyzed by multi-variate Poisson regression.

Results

The prevalence of OLP increased significantly from 1.3 (per 105) in 1996 to 12.8 (per 105) in 2013 (p for trend < 0.001). The prevalence was higher among female than male (RR: 2.13; 95% CI: 2.07–2.18, p < 0.001). The subjects living in suburban area had a lower risk of OLP than those living in urban area (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.78–0.82, p < 0.001). The higher income group had higher risk of OLP compared with the lower income group (RR, 2.27; 95% CI, 2.17–2.36, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The prevalence of OLP in Taiwan significantly increased over the past 18 years. The mean age with OLP was shown in an increased pattern. In addition, OLP occurs more frequently in women than in men.

Keywords: Oral lichen planus, Prevalence, National health insurance, Taiwan

Introduction

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a common chronic inflammatory disease associated with immune cell-mediated dysfunction that involves the oral mucosal stratified squamous epithelium and the underlying lamina propria and may be accompanied by skin lesions.1 The etiology and pathogenesis of OLP are not clearly understood. Some potential external and internal etiologic events such as genetic background, autoimmunity, hepatitis C virus, and psychological stress have been suggested to trigger OLP.2,3 Previously, higher expression of serum matrix metalloproteinase-24 and abnormally high blood homocysteine level5 were associated with OLP. In addition, the deficiencies of hemoglobin, iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12 were found in OLP patients as compared with healthy controls.5,6

The estimated prevalence of OLP is about 0.22%–5% worldwide.7 In general, females more suffer from OLP than males.8,9 In Taiwan, the prevalence of OLP was about 1.1%–9.8% from hospital based oral mucosal lesions examination.10, 11, 12 OLP has been recognized by the World Health Organization as an oral potentially malignant disorder.13 The malignant transformation rate of OLP was between 0 and 3.5% reported by a systematic review.14 The malignant transformation rate of OLP was surveyed about 0.52–2.1% in southern Taiwan.11,12 In addition, OLP has also been linked to psychological stress such as anxiety and depression.2,3 Any discomfort from OLP itself, or anxiety about the malignant potential, might be responsible for a worsening psychological status. Therefore, it is important for the dentists or physicians to remind OLP patients for regular follow-up.

Taiwan has launched a single-payer National Health Insurance (NHI) program on March 1, 1995 and covered up to 99% of the nation's inhabitants in 2014.15 The National Health Research Institute established the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) with registration files and original claim data for reimbursement. NHIRD has provided the useful epidemiological information for epidemiologic and clinical researches in Taiwan.16, 17, 18, 19, 20

In Taiwan, the nation scale survey of OLP stratified on the basis of demographic information has not been conducted so far. We therefore performed this nationwide population-based study in attempt to estimate the prevalence of OLP from NHIRD. This study also investigated whether the variations of age, sex, income, and urbanization factors influenced the prevalence of OLP in Taiwan.

Materials and methods

Data source

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board at the Chung Shan Medical University Hospital. The dental dataset (DN), original dental claim data, was used for this study. In addition, the registration data of all beneficiaries was used to evaluate gender, age, income, and geographic location of OLP patients from 1996 to 2013.

Patient identification and measurements

The diagnostic code of NHI in Taiwan is according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The OLP patient was identified with ICD-9-CM code of 697.0. Age groups were stratified into elder people (≧ 65 years) and non-elder people (<65 years). The payroll bracket (monthly income) was categorized as follows: New Taiwan Dollar $21,900, $21,901–43,900, and >$43,900. The urbanization of the locations of NHI registration was used as a proxy parameter for socioeconomic status. Urbanization was categorized 3 levels: urban, suburban, and rural areas based on the classification scheme as described previously.21

Statistical analysis

The annual prevalence rate of OLP by sex and age group in Taiwan from 1996 to 2013 was examined by trend test. The relative ratio of OLP after adjusting for year, urbanization, or payroll bracket was evaluated by multivariate Poisson regression. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

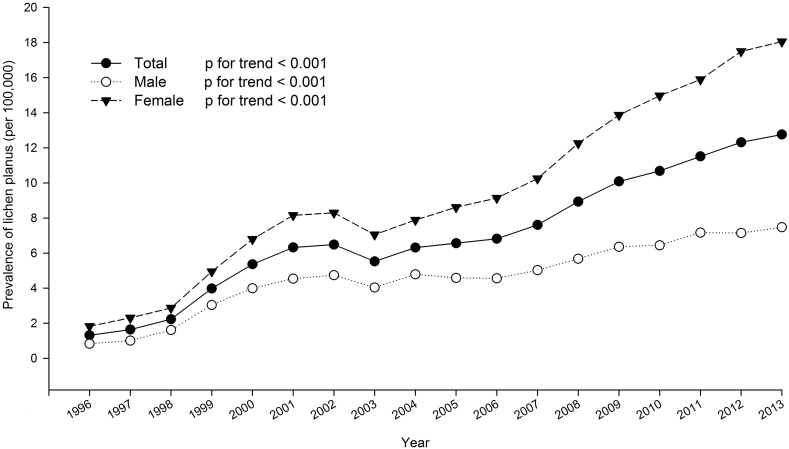

The sex-specific annual prevalence of OLP from 1996 to 2013 is presented in Table 1. The average male-to-female ratio was 0.522. The prevalence of OLP increased significantly from 1.3 (per 105) in 1996 to 12.8 (per 105) in 2013. The average annual prevalence was 7.022 (per 105). As shown in Fig. 1, the annual prevalence significantly increased during past 18 year period (p for trend < 0.001). The relative ratio (RR) of OLP by multivariate Poisson regression demonstrated in Table 2. The risk increased in annual increments (RR: 1.08; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.07–1.08, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Prevalence of lichen planus in Taiwan.

| Year | Total |

Male |

Female |

sex ratio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. of Lichen planus | P | N | No. of Lichen planus | P | N | No. of Lichen planus | P | ||

| 1996 | 21,525,433 | 283 | 1.3 | 11,065,798 | 92 | 0.8 | 10,459,635 | 191 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| 1997 | 21,742,815 | 357 | 1.6 | 11,163,764 | 113 | 1.0 | 10,579,051 | 244 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| 1998 | 21,928,591 | 489 | 2.2 | 11,243,408 | 182 | 1.6 | 10,685,183 | 307 | 2.9 | 0.6 |

| 1999 | 22,092,387 | 880 | 4.0 | 11,312,728 | 344 | 3.0 | 10,779,659 | 533 | 4.9 | 0.6 |

| 2000 | 22,276,672 | 1195 | 5.4 | 11,392,050 | 455 | 4.0 | 10,884,622 | 739 | 6.8 | 0.6 |

| 2001 | 22,405,568 | 1417 | 6.3 | 11,441,651 | 520 | 4.5 | 10,963,917 | 894 | 8.2 | 0.6 |

| 2002 | 22,520,776 | 1461 | 6.5 | 11,485,409 | 544 | 4.7 | 11,035,367 | 915 | 8.3 | 0.6 |

| 2003 | 22,604,550 | 1249 | 5.5 | 11,515,062 | 465 | 4.0 | 11,089,488 | 782 | 7.1 | 0.6 |

| 2004 | 22,689,122 | 1433 | 6.3 | 11,541,585 | 553 | 4.8 | 11,147,537 | 879 | 7.9 | 0.6 |

| 2005 | 22,770,383 | 1495 | 6.6 | 11,562,440 | 530 | 4.6 | 11,207,943 | 965 | 8.6 | 0.5 |

| 2006 | 22,876,527 | 1560 | 6.8 | 11,591,707 | 529 | 4.6 | 11,284,820 | 1031 | 9.1 | 0.5 |

| 2007 | 22,958,360 | 1746 | 7.6 | 11,608,767 | 583 | 5.0 | 11,349,593 | 1163 | 10.2 | 0.5 |

| 2008 | 23,037,031 | 2058 | 8.9 | 11,626,351 | 660 | 5.7 | 11,410,680 | 1398 | 12.3 | 0.5 |

| 2009 | 23,119,772 | 2332 | 10.1 | 11,636,734 | 740 | 6.4 | 11,483,038 | 1592 | 13.9 | 0.5 |

| 2010 | 23,162,123 | 2475 | 10.7 | 11,635,225 | 750 | 6.4 | 11,526,898 | 1725 | 15.0 | 0.4 |

| 2011 | 23,224,912 | 2674 | 11.5 | 11,645,674 | 834 | 7.2 | 11,579,238 | 1840 | 15.9 | 0.5 |

| 2012 | 23,315,822 | 2871 | 12.3 | 11,673,319 | 834 | 7.1 | 11,642,503 | 2037 | 17.5 | 0.4 |

| 2013 | 23,373,517 | 2983 | 12.8 | 11,684,674 | 873 | 7.5 | 11,688,843 | 2110 | 18.1 | 0.4 |

P: prevalence rate per 100,000 population.

Figure 1.

Time trends for the prevalence of OLP in Taiwan. The prevalence of OLP increased significantly from 1996 to 2013.

Table 2.

Relative ratio (RR) of lichen planus from 1996 to 2013 by multivariate Poisson regression.

| RRa | 95% C.I. |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Year (per 1 year) | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.08 | <0.001 |

| Age (ref: <65) | ||||

| ≧65 | 3.83 | 3.73 | 3.94 | <0.001 |

| Gender (ref: Male) | ||||

| Female | 2.13 | 2.07 | 2.18 | <0.001 |

| Urbanization (ref: Urban) | ||||

| Suburban | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.82 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.06 | 0.442 |

| Payroll bracket (ref: ≦NT $21900) | ||||

| NT $21901∼$43900 | 1.80 | 1.75 | 1.86 | <0.001 |

| >NT $43900 | 2.27 | 2.17 | 2.36 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for year, age, gender, urbanization and payroll bracket.

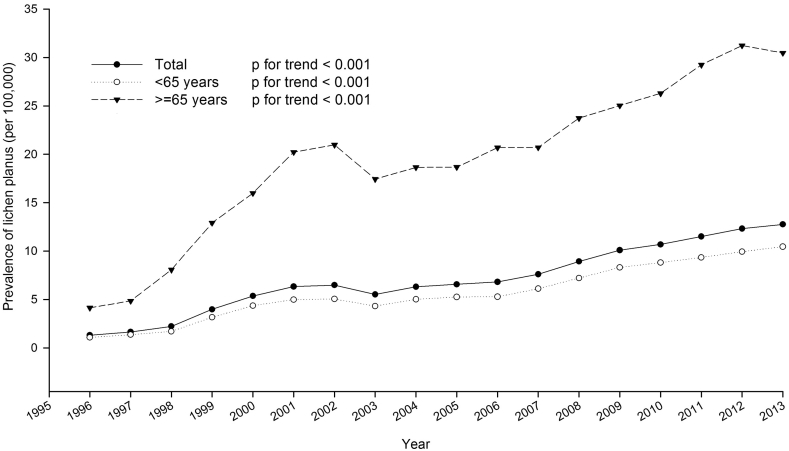

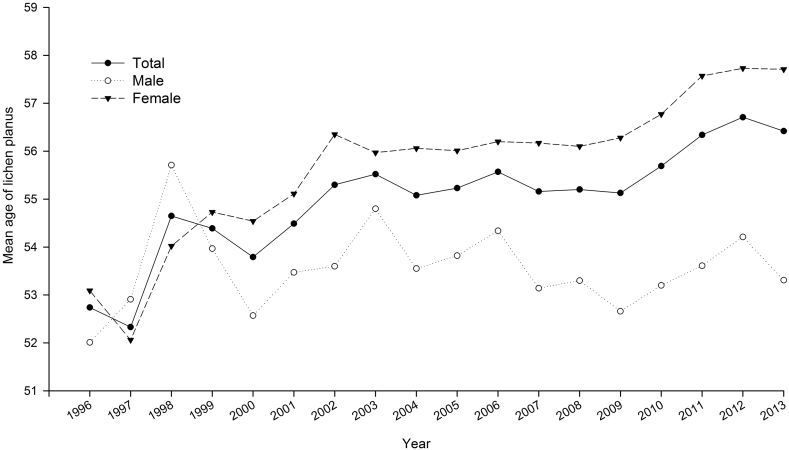

The prevalence of OLP stratified by age is shown in Fig. 2. The prevalence of OLP in both non-elder and elder groups demonstrated an increasing tendency (p for trend < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 3, the mean age of patients with OLP was within the range from 52.3 to 56.7 years old. The mean age in male group was 53.57 years old and 55.7 years old in female group. As demonstrated in Table 2, the elder group had higher risk of OLP (RR: 3.83; 95% CI: 3.73–3.94, p < 0.001). The females had a significantly higher OLP risk than males (RR: 2.13; 95% CI: 2.07–2.18, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Age-specific group in the prevalence of OLP in Taiwan from 1996 to 2013.

Figure 3.

The mean age of patients with OLP showed an increasing pattern from 1996 to 2013 for female.

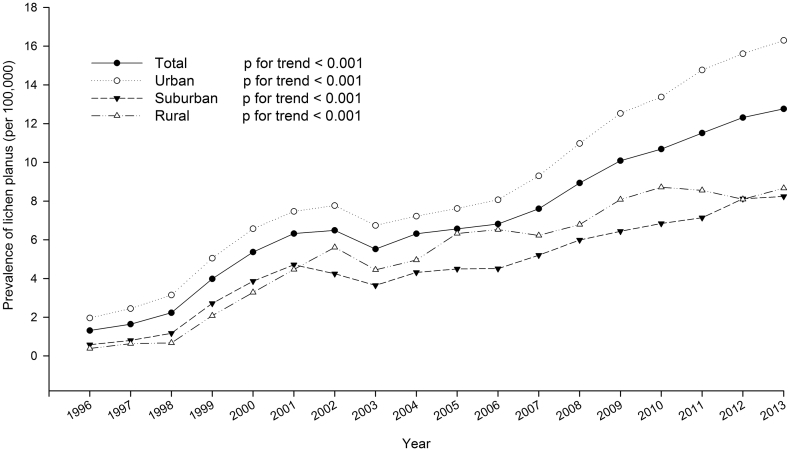

The prevalence of OLP analyzed by urbanization is shown in Fig. 4. The prevalence of OLP in urban, suburban, and rural populations all demonstrated in an increasing pattern (p for trend < 0.001). As shown in Table 2, the population dwelling in suburban had a lower risk of OLP than those living in urban areas (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.78–0.82, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

The prevalence of OLP in urban, suburban, and rural populations all demonstrated an increasing pattern from 1996 to 2013 (p < 0.001).

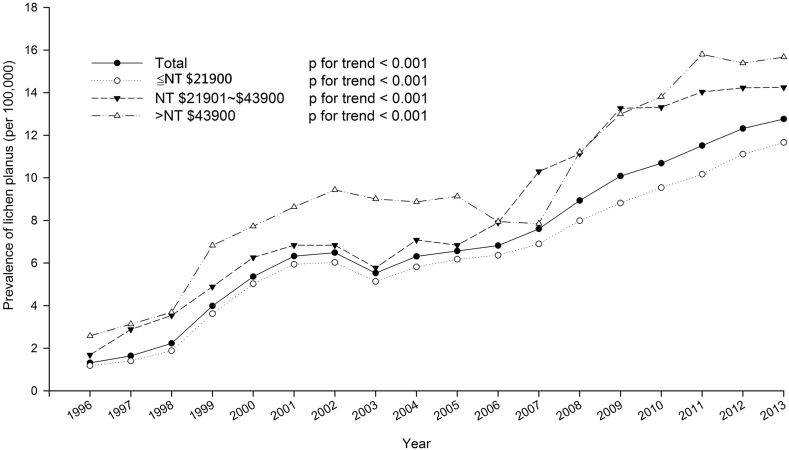

The prevalence of OLP analyzed by payroll bracket is shown in Fig. 5. The prevalence in all three groups demonstrated an increasing pattern (p for trend < 0.001). As shown in Table 2, the middle class group and upper class group had a higher risk of OLP than the lower class group (RR: 1.80; 95% CI, 1.75–1.86 and RR: 2.27; 95% CI: 2.17–2.36, respectively).

Figure 5.

The prevalence of OLP analyzed by payroll bracket in Taiwan. The prevalence of OLP in all groups demonstrated an increasing pattern from 1996 to 2013 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large-scale, retrospective, and longitudinal population based study to investigate OLP in Taiwan. We found the prevalence of OLP increased significantly from 1.3 (per 105) in 1996 to 12.8 (per 105) in 2013. However, the prevalence of OLP is much lower as compared with recent comprehensive review7 and even the previous reports from medical centers in northern12 and southern10,11 Taiwan. In addition, the prevalence of OLP was demonstrated about 0.81% in a cross survey of the community-dwelling inhabitants in Shanghai city.9 The prevalence of OLP in the Arab population studied was 1.8% from one university hospital22 and 0.412% in south Indian population from one dental college hospital.23

The reasons may explain as follows. The prevalence of OLP in previous studies was based on the oral examinations of oral mucosal lesions and especial for the high-risk group with alcohol intake, betel quid chewing, and smoking. In this study, the prevalence of OLP was analyzed by NHIRD based on ICD-9 diagnostic code. OLP might be markedly under-estimated because of clinical painless oral lesion with relative lower/no dental visit and medical-care seeking. Compared to previous studies, this study is a nationwide population register based study. Therefore, the prevalence of OLP might be underestimated by the use of NHIRD.

However, our results discover the important findings that the prevalence of OLP was significantly increased nearly every year from 1996 to 2013. This phenomenon may be due to the awareness of oral mucosal health in Taiwan. The government launched a free oral cancer screening health promotion program in 1990 for higher risk those who are the current/ex alcohol drinkers, betel-quid chewers, or cigarette smokers to receive oral examination. The patients with suspected pre-cancer lesions will be referred to hospitals with biopsy management for histological confirmation. This policy could increase the early diagnosis and treatment of OLP in Taiwan.

The level of urbanization reflects the socio-economic status. Urbanization may affect mental health through the influence of increased stressors and many environment factors. Anxiety and depression are more prevalent among urban women than men, and socioeconomic stress is considered to be affecting mental health of women based on the levels of urbanization.24 Recent reports have shown that a high correlation between anxiety, depression, and psychological stress with symptoms of OLP. 25, 26 In contrast, the results of this study varied from previous studies. Therefore, the level of urbanization may not be suitable since Taiwan is densely-populated. It follows that regional area variations might influence the prevalence of OLP.

The higher income group had a higher risk of OLP. This socioeconomic status actually implies more resources like knowledge, power, and other beneficial connections to avoid the risk of disease. Socioeconomic variables exhibit significant effect on the utilization of outpatient visits. The patients' attitudes toward dental treatment could also influence people's utilization of NHI in Taiwan. This may explain the phenomenon that the higher income people seek for medical care more frequently compared to the lower income individuals.

The power of this study is the use of a nationwide population-based database that can provide a sufficient sample size. However, there are still some limitations in this study. First, the diagnosis of OLP was only based on ICD-9 code. The site of occurrence of OLP cannot be obtained from NHIRD. In addition, the potential different outcomes may vary about clinical or histopathological diagnoses. The additional histopathological confirmation of OLP is required for further studies. Second, the included patients may have cutaneous lichen planus simultaneously. However, the data was extracted from original dental claims to make sure the validation of the diagnosis accuracy of lesions located in the oral cavity. Third, the information retrieved from this database did not contain the genetic background, autoimmunity, hepatitis C virus, behaviors, and psychosocial status. Nevertheless, the possible effects due to confounding bias from above factors might be minimized by adjusting for year, gender, age, urbanization, and income.

Although this retrospective study has the limitations, no similar study has been conducted among the Taiwanese population currently. The present study revealed the prevalence of OLP in Taiwan significantly increased over the past 18 years. OLP is more frequent in women.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 106-2632-B-040-002) in Taiwan.

References

- 1.Cheng Y.S., Gould A., Kurago Z., Fantasia J., Muller S. Diagnosis of oral lichen planus: a position paper of the American academy of oral and maxillofacial pathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:332–354. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurago Z.B. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhary S. Psychosocial stressors in oral lichen planus. Aust Dent J. 2004;49:192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai L.L., Yang S.F., Tsai C.H., Chou M.Y., Chang Y.C. Concomitant upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in lesions and circulating plasma of oral lichen planus. J Dent Sci. 2009;4:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H.M., Wang Y.P., Chang J.Y., Wu Y.C., Cheng S.J., Sun A. Significant association of deficiencies of hemoglobin, iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12 and high homocysteine level with oral lichen planus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang J.Y., Wang Y.P., Wu Y.H., Su Y.X., Tu Y.K., Sun A. Hematinic deficiencies and anemia statuses in anti-gastric parietal cell antibody-positive or all autoantibodies-negative erosive oral lichen planus patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorouhi F., Davari P., Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. Sci World J. 2014;2014:742826. doi: 10.1155/2014/742826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCartan B.E., Healy C.M. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: a review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng J., Zhou Z., Shen X. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai, China. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44:490–494. doi: 10.1111/jop.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsue S.S., Wang W.C., Chen C.H., Lin C.C., Chen Y.K., Lin L.M. Malignant transformation in 1458 patients with potentially malignant oral mucosal disorders: a follow-up study based in a Taiwanese hospital. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y.Y., Tail Y.H., Wang W.C. Malignant transformation in 5071 southern Taiwanese patients with potentially malignant oral mucosal disorders. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang M.L., Hsieh Y.J., Tseng Y.L., Lin J.R., Chiang C.P. Oral mucosal lesions and developmental anomalies in dental patients of a teaching hospital in Northern Taiwan. J Dent Sci. 2014;9:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick S.G., Hirsch S.A., Gordon S.C. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:45–56. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, R.O.C . 2014-2015. National health insurance annual report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang P.Y., Su N.Y., Lu M.Y., Wei C., Yu H.C., Chang Y.C. Trends in the prevalence of diagnosed temporomandibular disorder from 2004 to 2013 using a Nationwide Health Insurance database in Taiwan. J Dent Sci. 2017;12:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang P.Y., Chen Y.T., Wang Y.H., Su N.Y., Yu H.C., Chang Y.C. Malignant transformation of oral submucous fibrosis in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46:1040–1045. doi: 10.1111/jop.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang S.F., Wang Y.H., Su N.Y. Changes in prevalence of pre-cancerous oral submucous fibrosis from 1996-2013 in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based retrospective study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T.Y., Chiu Y.W., Chen Y.Z. Malignant transformation of Taiwanese patients with oral leukoplakia: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu H.C., Chen T.P., Chang Y.C. Inflammatory bowel disease as a risk factor for periodontitis under Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database. J Dent Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2018.03.004. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C.Y., Hung Y.T., Chuang Y.L. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag. 2006;4:1–22. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassona Y., Scully C., Almangush A., Baqain Z., Sawair F. Oral potentially malignant disorders among dental patients: a pilot study in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:10427–10431. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.23.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varghese S.S., George G.B., Sarojini S.B. Epidemiology of oral lichen planus in a cohort of south Indian population: a retrospective study. J Cancer Prev. 2016;21:55–59. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2016.21.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srivastava K. Urbanization and mental health. Ind Psychiatr J. 2009;18:75–76. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.64028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gavic L., Cigic L., Biocina Lukenda D., Gruden V., Gruden Pokupec J.S. The role of anxiety, depression, and psychological stress on the clinical status of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:410–417. doi: 10.1111/jop.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alves M.G., do Carmo Carvalho B.F., Balducci I., Cabral L.A., Nicodemo D., Almeida J.D. Emotional assessment of patients with oral lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:29–32. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]