Abstract

Background

Given the complex and progressive nature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a precision medicine approach for diagnosis and treatment requires the identification of patient subgroups with biomedically distinct and actionable phenotype definitions.

Methods

Longitudinal patient-level data for 1160 AD patients receiving placebo or no treatment with a follow-up of up to 18 months were extracted from an integrated clinical trials dataset. We used latent class mixed modelling (LCMM) to identify patient subgroups demonstrating distinct patterns of change over time in disease severity, as measured by the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale score. The optimal number of subgroups (classes) was selected by the model which had the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion. Other patient-level variables were used to define these subgroups’ distinguishing characteristics and to investigate the interactions between patient characteristics and patterns of disease progression.

Results

The LCMM resulted in three distinct subgroups of patients, with 10.3% in Class 1, 76.5% in Class 2 and 13.2% in Class 3. While all classes demonstrated some degree of cognitive decline, each demonstrated a different pattern of change in cognitive scores, potentially reflecting different subtypes of AD patients. Class 1 represents rapid decliners with a steep decline in cognition over time, and who tended to be younger and better educated. Class 2 represents slow decliners, while Class 3 represents severely impaired slow decliners: patients with a similar rate of decline to Class 2 but with worse baseline cognitive scores. Class 2 demonstrated a significantly higher proportion of patients with a history of statins use; Class 3 showed lower levels of blood monocytes and serum calcium, and higher blood glucose levels.

Conclusions

Our results, ‘learned’ from clinical data, indicate the existence of at least three subgroups of Alzheimer’s patients, each demonstrating a different trajectory of disease progression. This hypothesis-generating approach has detected distinct AD subgroups that may prove to be discrete endophenotypes linked to specific aetiologies. These findings could enable stratification within a clinical trial or study context, which may help identify new targets for intervention and guide better care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13195-017-0332-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Precision medicine, Endophenotypes, Machine learning, Statistical learning, Latent class mixed models

Background

Despite substantial investments in research to find better Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapies, most drug development efforts end in failure [1–3]; to date, there are no generally effective therapies for AD [1]. Part of the reason for widespread failure of therapeutic development for Alzheimer’s may be due to treating all persons with the disease as if they were the same. One potential route to achieving successful and timely identification of effective therapies is to identify subgroups of patients who may be more responsive to existing and experimental interventions. Given the complexity and progressive nature of AD, there are likely to be distinctive phenotypes and genotypes that respond to candidate therapies differently, and therefore a precision approach to prevention and treatment is critical. Such an approach, where persons with the disease are considered based on an endotype, could identify therapeutics that could delay progression of disease to gain the 5-year window necessary to reduce incidence of the disease.

By employing a data-driven, statistical learning approach, we investigated whether distinct subgroups of AD were apparent in an integrated clinical trial dataset; and whether these subgroups were associated with specific clinical features or existing therapies that might have delayed AD progression. Here, we report that clinically meaningful subgroups can be identified and these might be used to stratify patient populations for better AD management and care.

Methods

Study participants and data

Data were derived from an integrated dataset of AD clinical trials and observational studies described previously [4, 5]. The datasets consisted of 18 studies from the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS, http://adcs.org) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, http://www.adni-info.org) conducted from 1993 to 2012 to analyse the decline in sores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale [6] (ADAS-cog), Clinical Dementia Rating—Sum of Boxes [7] (CDR-SB) scale and Mini-Mental State Examination [8] (MMSE) over time. The integrated dataset includes demographics information, cognitive assessments, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotyping, concomitant medication information and blood test data for a total of 4574 participants and 25,164 encounters. All diagnoses of AD were based on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria [9]. Routine use of different medications was captured from the concomitant medication logs using brand and generic names as the search terms. In this study we examined the use of statins, non-statin cholesterol-lowering drugs, AD medications, antidepressants, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oestrogens, diabetes medications, vitamin E, omega-3 and derivatives, and medications for long-term asthma management. Medication use was evaluated at the baseline visit of the study into which participants were recruited. A full list of drug groups and search terms is presented in Additional file 1; potential misspelling of drug names was not accounted for. From this dataset we selected those participants with a diagnosis of AD who were treated with placebo or not treated at all, resulting in data from 1160 participants. Of these, 16% of participants originated from the ADNI study while the remaining 84% originated from ADCS studies.

Latent class analysis

We used latent class mixed modelling (LCMM) with the aim of identifying subgroups of patients with statistically distinct changes in cognitive scores over time, as measured by the ADAS-cog. The observation period for each participant started at beginning of the study they were recruited into and continued for up to 18 months (with a mean ± SD follow-up of 12.8 ± 5.9 months).

We specified linear mixed-effects models with the ADAS-cog as the dependent/outcome variable. Mixed effects were used to account for the likely correlation of repeated measurements within the same participant. We used a linear specification for trajectory shape, and a linear term for time to specify the random effects of the model. The lcmm package in R version 3.2.3 [10] was used to fit the model. We tested the model for 1–10 latent classes and the optimal number of latent classes was assessed using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC); the model which had the lowest BIC was selected. At model convergence, a posterior probability of membership of the latent classes was calculated for each participant, who was then assigned exclusively to the class for which the highest probability was obtained. This exclusive class assignment was used in order to allow subsequent characterization of patient subgroups. Other a priori specified patient-level variables, such as medication use and blood test analytes, were used to define these subgroups’ distinguishing characteristics (a full list of these variables is presented in Additional file 2).

Statistical description of latent classes

Categorical patient characteristics (gender, race, marital status, originating trial/study and ApoE genotype) were contrasted for the latent classes using chi-square tests. Analyses of variance were applied to the continuous variables (age at baseline, baseline ADAS-cog, number of education years and the different blood analytes). Tukey’s method for avoiding type I error was used for post-hoc analysis. Blood analytes examined in this study include those measured in routine biochemistry and haematology tests (Additional file 2). Association of medication use with latent classes was explored with tests of binomial proportions.

To test for differences in the slopes (rate of change) of the ADAS-cog score between subgroups of patients, we used a mixed-effects model implemented in R (using the lme4 package [11]). The model included the group effect, the visit (time) effect and group-by-visit interactions.

All analyses were computed using R version 3.2.3. Results are presented as the main effect with a 95% confidence interval. A significance level of 5% was used for main inferences.

Results

A total of 1160 AD participants assigned to placebo or untreated arms from nine clinical trials/studies, with at least one assessment on the ADAS-cog (at baseline or thereafter), were included. These involved ADNI [12] and ADCS studies evaluating the effects of simvastatin [13], docosahexaenoic acid supplementation [14], oestrogen replacement therapy [15], B vitamin supplementation [16], rofecoxib or naproxen [17], huperzine A [18], valproate [19] and prednisone [20], selected for their inclusion of a placebo-treated arm and the availability of evaluations for an overlapping duration of follow-up. A total of 4856 observations (ADAS-cog scores) over a period of 18 months were included for our analysis. The number of observations per participant ranged from 1 to 10, with a mean ± SD of 4.2 ± 1.9 ADAS-cog scores per participant.

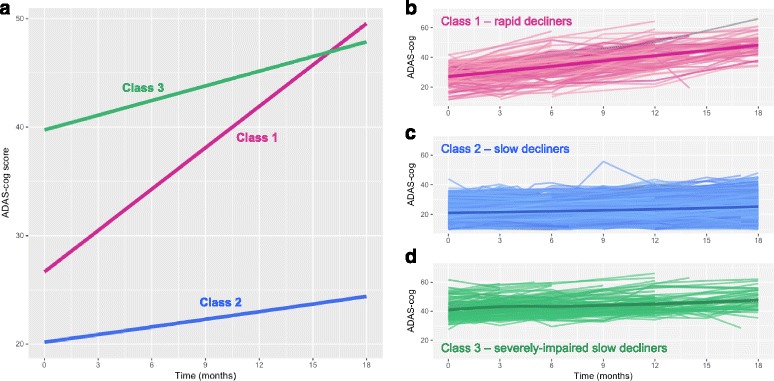

Our analysis of integrated data from these studies identified three subgroups of AD patients displaying unique trajectories of disease: 10.3% in Class 1, 76.5% in Class 2 and 13.2% in Class 3 (with mean posterior probabilities of 0.82, 0.93 and 0.79 respectively). All three classes, on average, exhibited cognitive decline over time. Participants within Class 2 and Class 3 exhibited moderate or slower cognitive decline (with varying starting points) whereas Class 1 demonstrated a steeper decline (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Three classes of ADAS-cog trajectories (higher score is associated with lower cognitive function/greater decline) in participants from placebo or no treatment arms of clinical trials/studies. a Disease progression trajectories estimated by our latent class mixed model, where an increase in ADAS-cog scores (y axis) indicates worsening of cognitive function. b–d Individual participant trajectories for each of the three resulting classes (each line represents a single participant). Bold lines represent a smoothing of the data; shaded areas represent the 0.95 confidence interval. ADAS-cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale

At baseline, no differences in gender, race, marital status or ApoE genotype were evident between the three classes of cognitive decline (Table 1). In addition, no differences in the rate of decline in cognitive scores were found between participants in placebo-treated arms and those who were not treated at all (the two treatment groups pooled in this dataset).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Entire cohort | Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 1160 | 119 | 888 | 153 |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 12.8 ± 5.9 | 13.6 ± 4.2 | 13.3 ± 5.7 | 9.1 ± 6.7 |

| Age | 75.6 ± 8.1 | 73.1 ± 8.9 | 76.1 ± 7.8 | 74.7 ± 8.6 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 590 (50.9) | 58 (48.7) | 443 (49.9) | 89 (58.2) |

| Male | 472 (40.7) | 50 (42.0) | 367 (41.3) | 55 (35.9) |

| Missing | 98 (8.4) | 11 (9.2) | 78 (8.8) | 9 (5.9) |

| Education | 14.0 ± 3.2 | 14.8 ± 3.2 | 13.9 ± 3.3 | 14.0 ± 2.9 |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 8 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 6 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| African American | 59 (5.1) | 6 (5) | 45 (5.1) | 8 (5.2) |

| White | 1007 (86.8) | 103 (86.8) | 771 (86.8) | 133 (86.9) |

| Other | 28 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 22 (2.5) | 6 (3.9) |

| Missing | 58 (5) | 9 (7.6) | 44 (5) | 5 (3.3) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Divorced | 70 (6.0) | 8 (6.7) | 55 (6.2) | 7 (4.6) |

| Married | 800 (69.0) | 90 (75.6) | 603 (67.9) | 107 (69.9) |

| Never married | 26 (2.2) | 3 (2.5) | 22 (2.5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Widowed | 243 (20.9) | 16 (13.4) | 195 (22.0) | 32 (20.9) |

| Missing | 21 (1.8) | 2 (1.7) | 13 (1.5) | 6 (3.9) |

| ApoE4 carriers (%)a | 63.5 | 65.7 | 63.6 | 62.6 |

| Statin users | 311 (26.8) | 23 (19.3) | 254 (28.4) | 34 (22.2) |

| Baseline ADAS-cog | 23.6 ± 9.6 | 26.5 ± 6.9 | 20.4 ± 6.7 | 40.9 ± 6.3 |

Baseline characteristics of participants in the entire cohort and in each of the resulting latent classes (in the three-class model). Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%) unless stated otherwise

ADAS-cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale, ApoE4 Apolipoprotein E, allele 4

aPercent of those participants with relevant information available

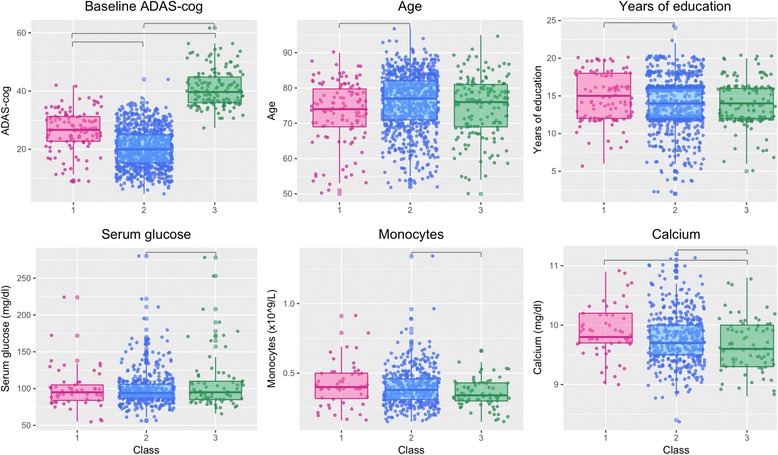

Participants in Class 1 were overall younger and had a higher mean number of years of education (significantly in comparison to Class 2, P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively; Fig. 2). Participants in Class 3 demonstrated the highest baseline ADAS-cog scores (P < 0.001), lower levels of monocyte counts and calcium levels (significantly in comparison to Class 2, P < 0.05) and the highest levels of serum glucose (P < 0.05; Fig. 2). Interestingly, Class 2 demonstrated the lowest baseline ADAS-cog scores and a significantly higher proportion of participants with a history of statin use (28.4% vs 19.3% in Class 1 and 22.2% in Class 3, P < 0.05). No significant differences between the resulting classes were found for the any of the other evaluated medication groups.

Fig. 2.

Baseline characteristics that are significantly different between the latent classes (subgroups of patients) identified from clinical trial/study data. Grey lines depict significantly different class pairs (determined by post-hoc analysis). ADAS-cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale

Discussion

To advance a precision medicine approach to AD, this study aimed to identify clinically relevant endophenotypes of AD, characterized by patterns of disease progression and clinical characteristics, which may prove to be biological endotypes.

We identified subgroups of patients based on a longitudinal analysis of high-quality integrated AD clinical trial data. We considered the possible existence of 1–10 subgroups/classes of disease progression. Using pre-defined criteria, the best fit was identified for a three-class model reflecting three subgroups of disease progression and cognitive decline. Class 1 was characterized by rapid and steep progression of cognitive decline: a mean decline > 10 points in the ADAS-cog. Class 3 was characterized by a greater cognitive deficit at baseline which increased modestly over time, while Class 2 displayed a lower level of cognitive deficit which did not reach the levels seen in Classes 1 and 3.

The three classes had differing clinical features. Class 1 patients tended to be younger and had more education, while those in Class 3 had lower monocyte counts and calcium levels, and higher levels of serum glucose. Age and severity of cognitive impairment have been reported previously as predictors of deterioration [5, 21, 22]. The importance of these characteristics is further demonstrated here, where younger age was found to be associated with a worse trajectory of progression (Class 1) and where lower baseline cognitive impairment was associated with slower decline (Class 2). Higher levels of education, as seen in Class 1, have also been found previously to be associated with risk for rapid cognitive decline [23]. There was no significant difference in gender, race, marital status and ApoE genotype across the three trajectory classes.

The most striking clinical features of the three classes were their pattern of cognitive decline—the structure of interest learned from the data, as well as the proportions of patient membership with each of the classes. The Class 1 rapid decline group had similar prevalence to the severely impaired slow progression phenotype Class 3, but most participants were in the Class 2 phenotype of low baseline cognitive deficit and slow progression of decline thereafter. These findings may have significant impact on powering clinical trials based on predicted magnitude of change over time and potential stratification. It may be the case that future clinical trials may want to consider focusing on recruitment of those patients who would be predicted to fall into Class 1 of rapid decliners as these may increase chances of success. However, the reliability of baseline characteristics in predicating class membership needs to be assessed and validated carefully, potentially in an independent cohort. Furthermore, since Class 1 covers only 10.3% of trial participants, recruiting only those patients would likely encumber trials, as the majority of AD subjects would be excluded. Additionally, to use these trajectories as a prognostic tool, future work should aim to validate our results in a cohort with a significant duration of follow-up, preferably of several years.

The ApoE4 allele is one of the most significant risk factors for sporadic AD [24]. Because the proportion of ApoE4 carriers within each class of disease progression did not significantly differ, ApoE4 genotype is unlikely to drive disease trajectories in the same way that it stratifies populations by the risk of developing AD, at least in mild to moderate AD clinical trial subjects and based on the cognitive measures tested in these. This observation is in agreement with other studies showing that ApoE4 does not significantly influence the rate of cognitive decline in AD [25, 26].

We have previously reported a subset of Alzheimer’s patients on statin therapy demonstrating improved cognitive function [27], supporting the existence of a responder subset of patients who would benefit from treatment with statins. By taking a different approach, these findings are further supported by analysis within the current study, where a subgroup (Class 2: lower ADAS-cog at baseline and slower decline) was also associated with a higher use of statins. Of the different medication types examined in this study, statin use was the only one to be statistically different between the resulting classes. However, it should be noted that this does not necessarily mean that other medications do not have potential therapeutic or preventative effects in AD. For example, it would be very difficult to draw conclusions regarding the effect of NSAIDs as these are not always taken on a regular basis. Unlike statins, diabetes medications, antidepressants or oestrogens, where it is likely that patients prescribed these are taking them on a regular and continuous basis, reported use of NASIDs at baseline might not reflect continuous use of these. Furthermore, here we examined the association of use of different medications with the different patient subgroups and trajectories. This is by no means an in-depth examination of any potential therapeutic effect; it may be the case that the association with statin use is confounded by other factors such as prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, differences in prescribing practices or better routine medical care.

A potential limitation of this study stems from the source and pooling of subjects from diverse clinical trials. Firstly, participants recruited into clinical trials may not accurately represent the more general AD patient population; a participant’s reason for joining a trial may differentiate them from the general population, introducing some bias. Secondly, by combining data from different trials, participant variability may be increased since selection criteria for each of these individual trials may have been different. However, since our study utilized data from participants within the placebo and no treatment arms of trials, variability was not influenced by treatment. Furthermore, by including subjects from multiple trials, we are more likely to capture the spectrum of AD patients who may enrol in future trials. Even with potential heterogeneity and variability across the years that studies were conducted, and inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the therapeutic intervention being tested, clinically meaningful subgroups with unique trajectories of disease progression were successfully detected.

This study has generated data-driven, plausible hypotheses about potential endotypes of AD, which could be used to repurpose or seek new targets for treatment or prevention. The unsupervised statistical learning technique used here has also been applied to type 2 diabetes, identifying meaningful patterns of pre-disease and BMI [28]. Similarly, model-based machine learning approaches have been used to discover important endotypes of allergy and asthma [29]. The growing use of unsupervised statistical and machine-learning methods, applied to large-scale patient-level data, shows great promise for better longitudinal characterization of AD. This may in turn lead to better precision diagnostics and more precise interventions. Future work should focus on identifying molecular biomarkers that distinguish between the trajectories identified here. This will provide more precisely defined endotypes which may be used to better stratify patients as well as inform on biological mechanisms driving disease progression.

Conclusion

We identified three clinical phenotypes of AD, with distinct trajectories of slow decline, severely impaired but slow decline, or rapid decline. Further research is needed to discover the biological mechanisms that may explain these subgroups as endotypes. Additionally, this study demonstrates how precision medicine approaches to AD can be informed by learning from existing datasets such as clinical trials. The findings presented here have the potential to contribute to more effective targeting of trials, medications and other interventions for the benefit of Alzheimer’s patients, thus potentially impacting AD patient management and care significantly.

Additional files

Full list of drug groups and search terms used to evaluate medication use at baseline (XLSX 42 kb)

List of a priori specified patient-level variables at baseline that were used to define the identified classes distinguishing characteristics (XLSX 40 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this work was enabled by the National Institute on Aging grants R34 AG049652 “Systems Pharmacology for Predictive Alzheimer’s Therapeutics: SysPharmRx-AD” and by P01 AG026572 (to RDB), and by the Medical Research Council and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council grant MR/N00583X/1 “Manchester Molecular Pathology Innovation Centre (MMPathIC): bridging the gap between biomarker discovery and health and wealth” (to NG/IB).

The Alzheimer's disease clinical trial meta-dataset development was supported by the National Institute of Health R01 AG037561 “Synthesis of Longer-term Alzheimer Disease Studies in Order to Model and Improve Clinical Trials Methods and Outcomes” (to LSS).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in this study are available from the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS, http://adcs.org) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, http://www.adni-info.org); restrictions/licensing may apply to the availability of these data.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAS-cog

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale—cognitive subscale

- ADCS

Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study

- ADNI

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- ApoE4

Apolipoprotein E, allele 4

- BIC

Bayesian Information Criterion

- BMI

Body mass index

- CDR-SB

Clinical Dementia Rating—Sum of Boxes

- LCMM

Latent class mixed models

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NSAID

non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

NG designed the study and carried out the analyses presented in this article. REK and LSS provided the meta-database of clinical trials and contributed to the analysis of this dataset. NG, REK, LSS, IB and RDB all contributed to the writing of the manuscript and to valuable discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No non-financial conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

Within 3 years of the beginning of this work, LSS has received grant and research support from Biogen, Genentech, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Roche, Tau Rx and NIH; and has served as a consultant for, and received consulting fees from, AC Immune, Axovant, Cerespir, Cognition, Insys, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Octapharma, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Tau Rx, Toyama, vTv and Zinfandel.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nophar Geifman, Phone: +44 161 2751125, Email: nophar.geifman@manchester.ac.uk.

Richard E. Kennedy, Email: richardkennedy@uabmc.edu

Lon S. Schneider, Email: lschneid@usc.edu

Iain Buchan, Email: Iain.Buchan@microsoft.com.

Roberta Diaz Brinton, rbrinton@email.arizona.edu.

References

- 1.Cummings JL, Morstorf T, Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(4):37. doi: 10.1186/alzrt269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PhRMA - Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. Researching Alzheimer’s Medicines: Setbacks and Stepping Stones. 2012. Available from: http://phrmadocs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/alzheimersetbacksreport.pdf.

- 3.Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M. Why do trials for Alzheimer's disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(6):735–9. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1323868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, Schneider LS. Effect of APOE genotype status on targeted clinical trials outcomes and efficiency in dementia and mild cognitive impairment resulting from Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3):349–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider LS, Kennedy RE, Wang G, Cutter GR. Differences in Alzheimer disease clinical trial outcomes based on age of the participants. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1121–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(11):1356–64. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.lcmm: Extended Mixed Models Using Latent Classes and Latent Processes. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lcmm/index.html

- 11.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.5823. 2014.

- 12.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR, Jr, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sano M, Bell KL, Galasko D, Galvin JE, Thomas RG, van Dyck CH, Aisen PS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of simvastatin to treat Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77(6):556–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228bf11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn JF, Raman R, Thomas RG, Yurko-Mauro K, Nelson EB, Van Dyck C, Galvin JE, Emond J, Jack CR, Jr, Weiner M, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1903–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, van Dyck CH, Sano M, Doody R, Koss E, Pfeiffer E, Jin S, Gamst A, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1007–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aisen PS, Schneider LS, Sano M, Diaz-Arrastia R, van Dyck CH, Weiner MF, Bottiglieri T, Jin S, Stokes KT, Thomas RG, et al. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(15):1774–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, Davis KL, Farlow MR, Jin S, Thomas RG, Thal LJ, et al. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2819–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafii MS, Walsh S, Little JT, Behan K, Reynolds B, Ward C, Jin S, Thomas R, Aisen PS. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative S. A phase II trial of huperzine A in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76(16):1389–94. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318216eb7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tariot PN, Schneider LS, Cummings J, Thomas RG, Raman R, Jakimovich LJ, Loy R, Bartocci B, Fleisher A, Ismail MS, et al. Chronic divalproex sodium to attenuate agitation and clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):853–61. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aisen PS, Davis KL, Berg JD, Schafer K, Campbell K, Thomas RG, Weiner MF, Farlow MR, Sano M, Grundman M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of prednisone in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Neurology. 2000;54(3):588–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.54.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs D, Sano M, Marder K, Bell K, Bylsma F, Lafleche G, Albert M, Brandt J, Stern Y. Age at onset of Alzheimer's disease: relation to pattern of cognitive dysfunction and rate of decline. Neurology. 1994;44(7):1215–20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.7.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortimer JA, Ebbitt B, Jun SP, Finch MD. Predictors of cognitive and functional progression in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1992;42(9):1689–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.9.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scarmeas N, Albert SM, Manly JJ, Stern Y. Education and rates of cognitive decline in incident Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):308–16. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strittmatter WJ, Roses AD. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(11):4725–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleiman T, Zdanys K, Black B, Rightmer T, Grey M, Garman K, Macavoy M, Gelernter J, van Dyck C. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele is unrelated to cognitive or functional decline in Alzheimer's disease: retrospective and prospective analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(1):73–82. doi: 10.1159/000093316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bracco L, Piccini C, Baccini M, Bessi V, Biancucci F, Nacmias B, Bagnoli S, Sorbi S. Pattern and progression of cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: role of premorbid intelligence and ApoE genotype. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(6):483–91. doi: 10.1159/000111081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geifman N, Brinton RD, Kennedy RE, Schneider LS, Butte AJ. Evidence for benefit of statins to modify cognitive decline and risk in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0237-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vistisen D, Witte DR, Tabak AG, Herder C, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, Faerch K. Patterns of obesity development before the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: the Whitehall II cohort study. PLoS Med. 2014;11(2):e1001602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazic N, Roberts G, Custovic A, Belgrave D, Bishop CM, Winn J, Curtin JA, Hasan Arshad S, Simpson A. Multiple atopy phenotypes and their associations with asthma: similar findings from two birth cohorts. Allergy. 2013;68(6):764–70. doi: 10.1111/all.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full list of drug groups and search terms used to evaluate medication use at baseline (XLSX 42 kb)

List of a priori specified patient-level variables at baseline that were used to define the identified classes distinguishing characteristics (XLSX 40 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS, http://adcs.org) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, http://www.adni-info.org); restrictions/licensing may apply to the availability of these data.