Abstract

Objective:

To test the long-term effect on growth status at 24 months in formula-fed infants who were randomized to consume a meat- or dairy-based complementary diet from 5 to 12 months.

Study design:

Observational assessments, including anthropometric, dietary and blood biomarkers, were conducted at 24 months, one year after the intervention ended.

Results:

The retention rate at 24 months was 84% for the Meat group and 81% for the Dairy group. Mean (± SD) protein intakes at 24 months were 4.1 ± 1.2 and 4.0 ± 1.1 g/kg/day for Meat (n=27) and Dairy (n=26) groups, respectively, and comparable with the estimates of U.S. population intake. At 24 months, weight-for-age Z score (WAZ) did not differ significantly between groups and was similar to that at 12 months. Length-for-age Z score (LAZ) remained significantly higher in the Meat group compared with the Dairy group, and the average length was 1.9 cm greater in the Meat group. Weight-for-length Z score (WLZ) also did not differ significantly between groups. IGF-1 significantly increased from 12 to 24 months in both groups, but IGFBP3 and BUN did not change significantly from 12 to 24 months and was comparable between groups.

Conclusions:

The protein source-induced distinctive growth patterns observed during infancy persisted at 24 months, suggesting a potential long-term impact of early protein quality on growth trajectories in formula-fed infants.

Complementary foods are the first source of diet diversification in infants as they transition from sole intake of breastmilk and/or formula. Evidence-based dietary recommendations of complementary feeding are critical to informing feeding practices, which, in turn, may affect growth trajectory and later obesity. Among various dietary determinates of growth, protein has been of special interest and consensus holds that the high protein content in infant formula drives the observed accelerated weight gain in formula-fed infants (1). Moreover, protein quantity during complementary feeding was also found to be associated with increased overweight risk and later obesity. One epidemiologic study in the U.K. showed that a higher proportion of energy from protein during complementary feeding was associated with higher weight and BMI (2); similar results were found in other studies (3, 4). Overall, it appears that there is a positive association between protein quantity and weight status early in life and the current dietary recommendation is to limit protein intake to 15% of energy during the first 2 years of life, without clear distinction for type of protein (5).

Emerging research suggests differential impact on growth and weight gain in infants and young children consuming protein from meat, dairy and plant sources. In one observational study, dairy protein intake at 12 months was associated with BMI at 7 y, and protein from meat, plants, or cereal did not have the same effect (6), and it was the dairy protein that drove the significant association between protein intake and later BMI (6). Our group recently conducted a small randomized controlled trial that directly compared a high-protein, meat- vs dairy-based complementary diet in formula-fed infants from 5 to 12 months of age (7). We found that the dairy group had a relative deceleration of linear growth (decrease of LAZ), and the Meat group had an increase in linear growth (increase of LAZ). This distinctive linear growth pattern, plus the similar increases of weight and WAZ for both groups, led to a significant increase of 0.76 of weight-for-length Z score (WLZ) in the Dairy group from 5 to 12 months (7). Here we present the follow-up assessment on growth, dietary intake, and blood biomarkers of this cohort at 24 months. Our primary hypothesis is that the observed growth patterns during the intervention will persist at 24 months.

METHODS

Details of the study design and results of the intervention phase from 5-12 months of age were previously reported (7). In brief, this study was a stratified, randomized controlled trial using semi-controlled feeding. Healthy five-month old formula-fed infants were provided the same cow-milk based infant formula and consumed a complementary diet with meat or dairy as the predominant protein source from 5-12 months; total protein intake was ~ 3 g/kg/day and equal to 15% of total energy. Diet records showed that during the intervention, over 90% of protein from solid foods was from the assigned protein group and <5% was from the alternative. The primary outcome was growth, measured as longitudinal change in weight (kg), length (cm), and respective age- and sex-specific Z scores. Growth indices were measured at baseline, end of intervention, and 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 months of age during the intervention. Blood samples were collected at 5 and 12 months to measure selected biomarkers. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02142647).

Follow-up assessment

The follow-up visit was conducted at 24 months of age, from June 2016 to August 2017. Parents or caregivers of the participants who completed the intervention were contacted by phone or email when the participant was between 23 and 24 months of age. Participants visited the Children’s Hospital Colorado Clinical & Translational Research Center (CTRC) at 24 months and signed the consent for this visit. During this visit, length, weight and blood samples were collected by the trained CTRC research nurses who were blinded of the group assignment; and all anthropometric measurements were performed in triplicate. Length was measured in recumbent position using an infantometer accurate to 0.1 cm (Holtain Ltc, Crosswell, Crymych, Pembs, UK). An electronic digital scale (Health o meter, McCook, IL) was used to obtain naked weight. Parents also completed a 3-day diet record. Diet records were analyzed by the CTRC nutrition core for total calories and macronutrient contents (NDSR software, Minneapolis, MN). Total protein intake was further broken down to various sources. After all the participants' 3-day food records were entered into NDSR, a CTRC dietitian exported the component/ingredient file. This file provided macro- and micronutrient data for each ingredient in the diet records, including grams of animal protein and plant protein. From this file, each participant's data were further separated into individual protein sources: liquid dairy (cow’s milk), solid dairy (yogurt, cheese), meat (chicken, beef, pork, lamb), fish, egg, and plant. Diet diversity score was also calculated at 24 months, based on the WHO infant and young child minimum dietary diversity score (8). Blood samples were centrifuged and serum was stored at −80°C until analyzed. The following markers were analyzed by the CTRC Core Lab: insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1, Chemilluminescence, DiaSorin Liaison), Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein 3 (IGFBP3, Chemilluminescence, Siemen), and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). The between assay precisions were <2.7% for IGF-1, <4.0% for IGFBP3 and <4.5% for BUN.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Results of growth Z scores, dietary intakes and blood biomarkers data are presented as mean ± SD. Repeated measures ANOVA (PROC GLM) were used to evaluate the main effects of time (12 to 24 months), group, and their interactions on the dependent variables between 12 and 24 months. The Student t test was used to compare values between groups at 24 months. All model assumptions were checked and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among all participants who completed the intervention (32 per group), 26 from the Dairy group and 27 from the Meat group completed the follow-up visit. The retention rate was similar between groups (Meat: 84%; Dairy: 81%). Of the 11 infants who did not complete the follow-up, 8 moved out of the state or country and 3 lost contact. Subject characteristics (birth weight, length, gestational age, and sex) did not differ between those who did not complete the study vs. those that completed. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of those participants who completed the 24 months visit.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics1

| Meat2 (n=27) | Dairy2 (n=26) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex3 | 48% male | 49% male | 0.67 |

| Birth weight4 (kg) | 3.33 ± 0.35 | 3.28 ± 0.45 | 0.65 |

| Gestational age4 (wk) | 39 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 0.77 |

| Maternal BMI4 | 27 ± 7 | 27 ± 6 | 0.70 |

| Maternal height4 (cm) | 167 ± 6 | 166 ± 8 | 0.22 |

| Maternal age4 (y) | 30 ± 6 | 30 ± 7 | 0.53 |

| 24 m weight4 (kg) | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 0.38 |

| 24 m length4 (cm) | 89.0 ± 2.3 | 87.1 ± 3.3 | 0.02 |

Mean ±SD

Meat: the meat-based complementary diet group; Dairy: the dairy-based complementary diet group

Chi-quare test

Independent Student’s t test

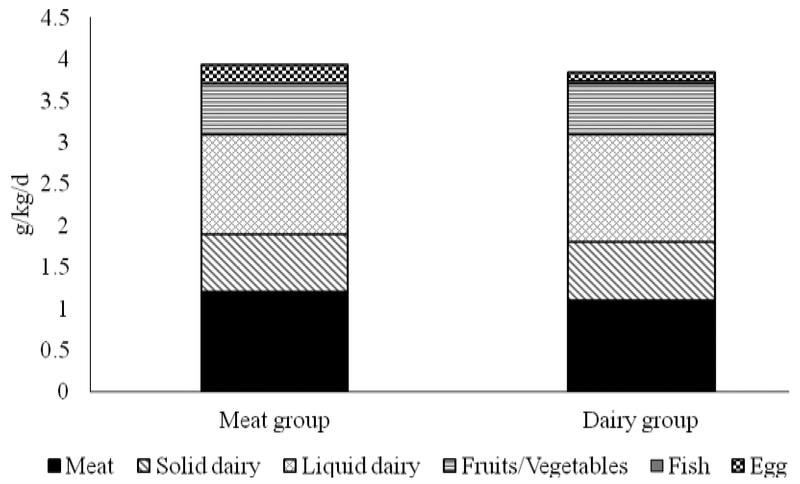

Dietary intake, including protein sources

Three-day diet records were collected on 19 subjects from the Meat group and 18 from the Dairy group. At 24 months, all participants consumed whole- or low-fat (2% fat) cow’s milk, except for one from the Dairy group who still consumed infant formula. Total protein intake was 4.06 ± 1.21 and 4.00 ± 1.10 g/kg/day for Meat and Dairy groups, respectively. Macronutrient distributions and total caloric intakes are presented in Table 2, and shows no difference between groups in macronutrient or caloric intakes. Total protein intakes were further categorized to various sources (Figure 1). Overall, there was no difference between groups for any source of protein consumed, except for egg protein, which was higher in the Meat group (0.24 ± 0.27 g/kg/d) than in the Dairy group (0.10 ± 0.15 g/kg/d) (P = 0.04). No difference of reported diet diversity was found between Meat and Dairy. The average scores were 4.74 ± 1.07 and 4.17 ± 1.01 for Meat and Dairy groups, respectively (P=0.11).

Table 2.

Macronutrient distributions and caloric intakes at 24 months1

| Meat2 (n=19) | Dairy2 (n=14) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total calories (kcal/d)3 | 1350 ± 565 | 1150 ± 370 | 0.21 |

| Total calories3 (kcal/kg/d) | 106 ± 48 | 97 ± 27 | 0.29 |

| Carbohydrate3 (g/kg/d) | 13.3 ± 5.1 | 12.4 ± 3.9 | 0.55 |

| Carbohydrate3 (%energy) | 50 ± 8 | 53 ± 6 | 0.32 |

| Fat3 (g/kg/d) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 0.23 |

| Fat3 (%energy) | 35 ± 7 | 32 ± 5 | 0.12 |

| Protein3 (g/kg/d) | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 0.45 |

| Protein3 (%energy) | 16 ± 3 | 16 ± 3 | 0.52 |

Mean ±SD

Meat: the meat-based complementary diet group; Dairy: the dairy-based complementary diet group

Independent Student’s t test

Figure 1. Protein intake at 24 months of age from different sources between groups1.

1Meat n=19; Dairy n=18; By independent Student t test between groups, only fish intake was different between groups and was higher in the Meat group (P = 0.04).

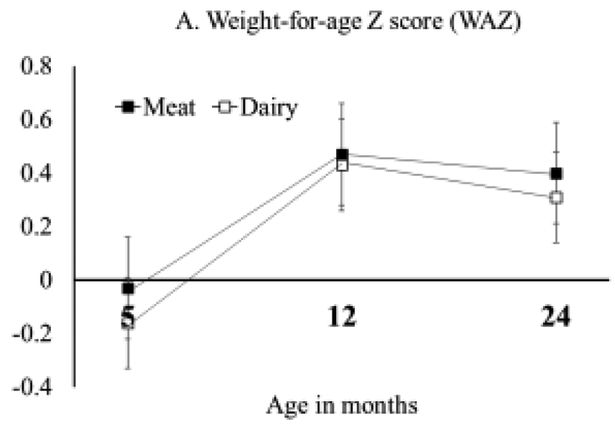

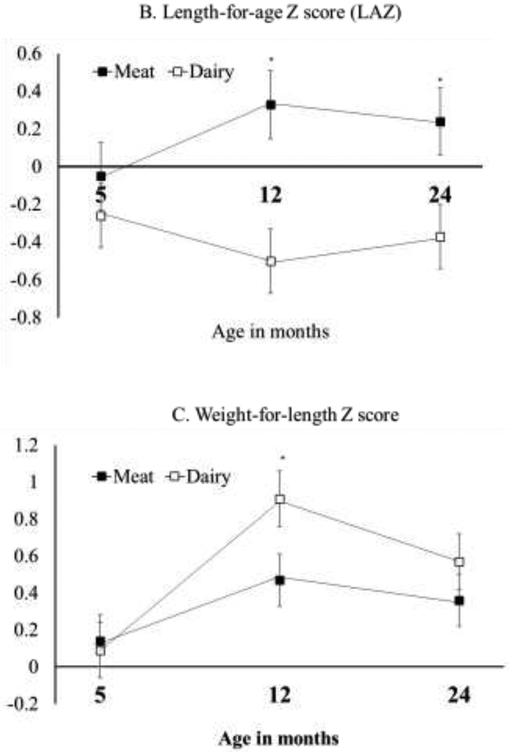

Anthropometric measurements at 24 months of age

Growth Z-scores (WAZ, LAZ, and WLZ) of the intervention and the follow-up are summarized in Figure 2. Data from the intervention (5 and 12 months) include only participants who completed the follow-up assessment at 24 months, and all the Z scores were considered well within normal range. WAZ did not differ significantly between groups at 24 months (P=0.65) or change significantly from 12 to 24 months (effect of time P=0.42). At 24 months, LAZ was still significantly higher in the Meat group (0.19 ± 0.62), compared with the Dairy group (−0.37 ± 0.88, P=0.01). Although the change in LAZ did not statistically differ from 12 to 24 months for either diet group (Meat: P=0.33; Dairy: P=0.23), the Dairy group had a slight increase of LAZ (+0.13 ± 0.12). This increase of LAZ, although not significant, produced WLZ values at 24 months that no longer differed between groups (P=0.40, Figure 2). Weight (kg) and length (cm) between groups at 24 months are presented in Table 1 and consistent with the growth Z scores. The average length was 1.9 cm higher in the Meat group compared with the Dairy group.

Figure 2: Growth Z score at 5, 12, and 24 months for participants who completed the 24 months assessment.

Repeated measure ANOVA comparing time (12 and 24 months), group (Meat and Dairy) and their interactions. Independent Student t test was used to compare between groups at 24 months. A: no significant differences pf WAZ between groups at 24 months (P=0.65) or over time (effect of time P=0.42); B: significant difference of LAZ at 24 months (P=0.01) but no change from 12 to 24 months for either groups (effect of time P=0.44); C: no significant difference between groups of WLZ at 24 months (P=0.40) or change over time (effect of time P=0.15).

Blood biomarkers

Tables 3 shows IGF-1, IGFBP3, and BUN concentrations by group. At 24 months, there were no significant differences in the IGF-1, IGFBP3, or BUN values between the Meat and Dairy groups. IGF-1 significantly increased from 12 to 24 months in both groups (effect of time P = 0.002) but no significant change was observed for IGFBP3 or BUN. Each of the average biomarker values remained within the normal range for this age.

Table 3.

IGF-1, IGFBP3 and BUN concentrations at 24 months in Meat and Dairy groups1

| IGF-1 (ng/ml) | IGFBP3 (ng/ml) | BUN (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal range | 29–186 (male) | 1269-4104 (male) | 7-26 |

| 19-147 (female) | 1198-4182 (female) | ||

| Meat2

(n=18) |

106 ±31 | 2784 ±498 | 15 ±3 |

| Dairy2

(n=16) |

97 ±29 | 2505 ± 462 | 14 ±3 |

| P value between groups | 0.44 | 0.13 | 0.49 |

Mean ±SD

Meat: the meat-based complementary protein group; Dairy: the dairy-based complementary protein group

DISCUSSION

Protein intake from complementary foods during infancy has important implications for growth. Our randomized controlled trial of formula-fed infants showed greater length gain in those who consumed meat compared with dairy from 5 to 12 months of life (7). This follow-up study at 24 months further demonstrated that the growth pattern observed during infancy persisted at 24 months, one year after the end of the intervention. Although LAZ did not differ between 12 and 24 months for either diet group, the slight (non-significant) increase of LAZ in the Dairy group made WLZ no longer different between groups at 24 months (Figure 2, C). LAZ was still significantly higher in the Meat group compared with Dairy at 24 months and the length difference between groups was comparable at 12 months (1.8 cm) (7) and 24 months (1.9 cm). These findings were consistent with our hypothesis that the protein-induced growth patterns at 12 months would persist after the intervention ended and further underscored the importance of early dietary patterns, especially protein quality, on long-term growth. Several studies have also shown that diet-induced weight gain during infancy has a prolonged impact on long-term growth and health (9-11).

One potential mechanism of protein intake and accelerated weight gain is the “early protein hypothesis”, which proposes that high protein intake increases circulating IGF-1 concentration, which enhances growth and weight gain (12). However, IGF-1 had a similar increase from 12 to 24 months in both groups in the present study and cannot explain the persistent differential linear growth patterns between groups. If it was indeed the effect of protein source consumed, dietary intakes may provide some insights. During the intervention, participants did not consume the assigned alternative protein source. For example, infants from the Dairy group consumed a minimum amount of meat (2%) from solid foods and vice versa (7).

After the intervention ended at 12 months of age, consumption of protein from meat or dairy sources were no longer restricted, and this resulted in a relative increase of meat consumption in infants from the Dairy group. The three-day diet records at 24 months showed that the infants consumed protein from various sources including both meat and dairy, and there were no significant differences between groups (Figure 1). Specifically, both groups consumed ~1 g/kg/d of protein from meat. This increase in meat intake in the Dairy group after the intervention could potentially explain the improved linear growth in the Dairy group at 24 months.

Research, especially randomized controlled trials, is quite limited for the association between protein intakes on infant growth during complementary feeding. A previous cohort of breastfed infants from Denver by our research team showed that consuming a meat-based complementary diet (2.7 g /kg/d) increased LAZ by an average of 0.27 and a low protein, cereal-based diet (1 g /kg/d) was associated with a decline in LAZ by an average 0.33 over 3 months (6-9 months of age) (13). Another study that randomized breastfed infants to consume a low-meat (19% energy) vs. high-meat (21% energy) diet from 4 to 10 months found no difference in length or weight gain (14). Similar intervention trials also did not find differences between high- vs. low-meat consumptions on growth in infants (15, 16). These studies, however, had iron status as the primary outcome, not growth (14-16), and the difference in protein quantity between groups were usually small. Thus, more high-quality research during the complementary feeding period is needed to elucidate the role of protein quality with growth as the primary outcome.

Participants at 24 months consumed a quantity of protein similar to the national average in the United States. Data from the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that infants aged 12-23 months consumed an average of 4.1 g/kg/d of protein (17), and the participants in our study consumed ~ 4 g/kg/d at 24 months. In addition, the most recent findings from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) (18) also reported that the median total protein intake for 12-23.9 months was 46 ± 0.4 g/d and the 75th percentile was 54 g/d, and in our study it was 49 ± 2 g/d at 24 months. Thus, overall, the amount of protein consumed at 24 months was comparable between diet groups and similar to national average for the U.S., suggesting that protein quantity at 24 months may not contribute to the persistent growth patterns observed from 12 to 24 months. In terms of carbohydrate, fat and energy, infants from the present study also had comparable intakes to the reported values in FITS (18).

One of the strengths of the study was that the research nurses at Children’s Hospital Colorado, who were blinded to the group assignment, conducted the anthropometric measurements for the 24-month visits. In addition, the protein source breakdown from the 3-day diet record was helpful to demonstrate protein intakes from meat, dairy and other common sources for this age group, although the dietary data was not from the full 24-month sample. One limitation was that we did not include a reference breastfed group for comparison with our participants who were formula-fed during infancy. Further, 6 participants from the Dairy group and 5 participants from the Meat group were lost to follow-up, which could create potential confounding, although subject characteristics at baseline did not differ between the participants who completed the study and those who did not. Finally, LAZ at 24 months in both the Meat and Dairy groups might reflect the possibility of a regression to the mean (19); and whether this trend will continue or not needs further research with longer follow-up time.

In summary, this follow-up observation to a randomized controlled trial suggests that consumption of meat-based complementary diet by formula-fed infants in the early complementary feeding period promotes linear growth, which persists at 2 years of life. Moreover, reintroducing meat to participants who consumed only dairy as the main protein source during infancy appeared to ameliorate the earlier decline of LAZ. However, the sample size was relatively small, and it is unclear whether this greater linear growth in the Meat group would have any health benefits in well-nourished infants and toddlers. To our knowledge, this is a novel example of how diet in the first year of life can impact short- and possibly longer-term growth patterns. The current Dietary Guidelines for Americans has very limited guidance for infants and children from birth to 24 months, due to limited evidence available. Findings from this study reinforce the need for more high-quality research on dietary patterns and nutrient intakes during the first two years of life in relation to the quality of growth.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIDDK) (1K01DK111665 [to M.T.]), NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA (UL1 TR001082 [to M.T., A.H., N.K.), and (alphabetically) Abbott Nutrition (to M.T. and N.K.), the American Heart Association (to M.T.), the Beef Checkoff through the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (to M.T. and N.K.), Leprino foods (to N.K.), and the National Pork Board (to M.T. and N.K.).

Abbreviations

- LAZ

length-for-age Z score

- WAZ

weight-for-age Z score

- WLZ

weight-for-length Z score

Footnotes

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02142647

No conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koletzko B, von Kries R, Closa R, Escribano J, Scaglioni S, Giovannini M, et al. Lower protein in infant formula is associated with lower weight up to age 2 y: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pimpin L, Jebb S, Johnson L, Wardle J, Ambrosini GL. Dietary protein intake is associated with body mass index and weight up to 5 y of age in a prospective cohort of twins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):389–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunther AL, Buyken AE, Kroke A. The influence of habitual protein intake in early childhood on BMI and age at adiposity rebound: results from the DONALD Study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(7):1072–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoppe C, Molgaard C, Thomsen BL, Juul A, Michaelsen KF. Protein intake at 9 mo of age is associated with body size but not with body fat in 10-y-old Danish children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fewtrell M, Bronsky J, Campoy C, Domellof M, Embleton N, Fidler Mis N, et al. Complementary Feeding: A Position Paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(1):119–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunther AL, Remer T, Kroke A, Buyken AE. Early protein intake and later obesity risk: which protein sources at which time points throughout infancy and childhood are important for body mass index and body fat percentage at 7 y of age? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(6):1765–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang M, Hendricks AE, Krebs NF. A meat- or dairy-based complementary diet leads to distinct growth patterns in formula-fed infants: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(5):734–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organization WH. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: part 1: definitions: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6-8 November 2007 in Washington DC, USA 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stettler N, Zemel BS, Kumanyika S, Stallings VA. Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monteiro PO, Victora CG, Barros FC, Monteiro LM. Birth size, early childhood growth, and adolescent obesity in a Brazilian birth cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(10):1274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas A Programming by early nutrition in man. Ciba Found Symp. 1991;156:38–50; discussion -5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koletzko B, Demmelmair H, Grote V, Prell C, Weber M. High protein intake in young children and increased weight gain and obesity risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):303–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang M, Krebs NF. High protein intake from meat as complementary food increases growth but not adiposity in breastfed infants: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(5):1322–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dube K, Schwartz J, Mueller MJ, Kalhoff H, Kersting M. Complementary food with low (8%) or high (12%) meat content as source of dietary iron: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2010;49(1):11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makrides M, Leeson R, Gibson R, Simmer K. A randomized controlled clinical trial of increased dietary iron in breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 1998;133(4):559–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelmann MD, Sandstrom B, Michaelsen KF. Meat intake and iron status in late infancy: an intervention study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahluwalia N, Herrick KA, Rossen LM, Rhodes D, Kit B, Moshfegh A, et al. Usual nutrient intakes of US infants and toddlers generally meet or exceed Dietary Reference Intakes: findings from NHANES 2009-2012. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(4):1167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey RL, Catellier DJ, Jun S, Dwyer JT, Jacquier EF, Anater AS, et al. Total Usual Nutrient Intakes of US Children (Under 48 Months): Findings from the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) 2016. J Nutr. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cockrell Skinner A, Goldsby TU, Allison DB. Regression to the Mean: A Commonly Overlooked and Misunderstood Factor Leading to Unjustified Conclusions in Pediatric Obesity Research. Child Obes. 2016;12(2):155–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]