Abstract

Background:

Patient satisfaction is a patient-centered outcome of particular interest. Previous work has suggested that global measures of satisfaction may not adequately evaluate surgical care; therefore, the surgery- specific S-CAHPS (Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) survey was developed. It remains unclear how traditional outcome measures such as morbidity impact patient satisfaction. Our aim was to determine whether NSQIP-defined complications impacted satisfaction with the surgeon as measured by a surgery-specific survey, the S-CAHPS.

Methods:

All patients undergoing a general surgical operation from 6/13–11/13 were sent the S-CAHPS survey after discharge. Retrospective chart review was conducted using NSQIP variable definitions, and major complications were defined. Data were analyzed as a function of response to the overall surgeon-rating item, and those surgeons rated as the “best possible” or “topbox” were compared with those rated lower. Univariate and logistic regression were used to determine variable importance.

Results:

529 patients responded, and 71.5% (378/529) rated the surgeon as topbox. The overall NSQIP complication rate was 14.2% (75/529) with 26.7% of those (20/75) being major complications. On univariate analysis, patients who rated their surgeon more highly were somewhat older (59 vs. 54yrs: p <0.001), more often underwent elective surgery (81% vs. 57%: p <0.001), and had an increased rate of operation for malignancy (31% vs. 17%). Neither the complication rate (total or major) nor the number of complications were associated with satisfaction scores.

Conclusions:

When examined on a patient-level with surgery-specific measures and outcomes, the presence of complications after an operation does not appear to be associated with overall patient satisfaction with surgeon care. This finding suggests that satisfaction may be an outcome distinct from traditional measures.

Keywords: Patient Satisfaction, NSQIP, Outcomes, CAHPS, patient-reported outcomes

INTRODUCTION

The implementation of Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) has linked patient satisfaction as measured by the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey to reimbursement 1,2. Despite this, it remains unclear which components of inpatient medical care are most important to patients, and further, if these xcomponents vary between clinically distinct subgroups (medical, surgical, and obstetric patients) 3,4. Concern for inadequate metrics for the surgical patient experience prompted the American College of Surgeons (ACS) to determine important components of surgical care and develop a surgery-specific satisfaction tool 5–8. This resulted in the development of the National Quality Forum-endorsed Surgery-CAHPS (S-CAHPS), which focuses on key areas of perioperative patient care, including preoperative, day of operation, and postoperative care 9.

Published experience with S-CAHPS to date has demonstrated that the survey can be implemented successfully in the clinical setting with an adequate response rate 10,11. An in-depth examination of the components of the survey at our academic center found that the factors associated most strongly with a favorable surgeon rating were preoperative communication and attentiveness on the day of operation11. These findings suggested that interpersonal communication was of central importance to patient satisfaction with surgical care. But, the relationship between satisfaction with surgical care as measured by S-CAHPS and the occurrence of postoperative complications has not been described.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between traditional outcome measures and patient satisfaction; however, these results have used a variety of tools and outcomes, and when considered overall, the strength of the relationship remains unclear 6,12–22. For example, on the hospital level, several studies have shown that hospitals with greater satisfaction were associated with quality of care in pneumonia, myocardial infarction 15, decubitus ulcer rates, and infections 16; however, other studies failed to demonstrate a consistent relationship 17–19. In studies focused on surgical patients, hospital level data have demonstrated a significant association between patient satisfaction and traditional outcomes of surgical quality 15,20. Sheetz et al , however, failed to reinforce this relationship 22. Although informative, these studies fail to make a direct comparison between individual patient events and individual patient scores, leaving the possibility for confounding factors in the interpretation of these results, while also explaining the divergent findings. In addition, previous patient level data have demonstrated an association between satisfaction and surgery outcomes, however; they have not used widely standardized, available, and surgery-specific outcomes measures such as the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Measures or other widely available patient satisfaction surveys 6,13,14. Still other studies have failed to demonstrate this relationship 21, again making the true relationship unknown. Further, interpretation of these results should be taken with caution, because none of these studies used a satisfaction tool specific to the surgery patient, such as the S-CAHPS.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether the presence of postoperative complications using well-accepted standardized definitions is associated with patient satisfaction with surgeon care as measured by a surgery-specific satisfaction survey (i.e. S-CAHPS). In addition, we aimed to describe the clinical and demographic variables that impact satisfaction in a large group of general surgery patients.

METHODS

Patients

All adult (≥18 years), English-speaking, patients who had an operation at a single institution with a general surgeon between June and November of 2013 were mailed the S-CAHPS survey within 1 week of discharge. Patients in prison were excluded. No incentives were given for completion of the survey, but an explanation of the purpose of the survey was included, namely to understand the factors that contribute to the satisfaction of their surgical care (a discussion of impact of complications on satisfaction was not included, because this minimal risk analysis was approved by the IRB after the survey data collection was completed). The daily hospital discharge list was examined by service and by surgeon to identify patients eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they did not undergo an operative procedure during that admission, did not have an overnight admission, or indicated that an incorrect surgeon was listed on the survey. Additionally, patients were excluded if they did not answer the overall, surgeon-rating item, because this item was the primary outcome. Secondary mailings were sent to non-responders for approximately the first 200 non-responders; however, secondary response rates remained low, and these secondary mailings were discontinued. Retrospective chart review was undertaken to gather a variety of additional clinical variables including postoperative complications. This study was undertaken after approval from our Institutional Review Board.

Survey

The S-CAHPS survey was used in an abbreviate form to focus on preoperative and day of operation care; postoperative questions were omitted (questions 26 – 34 in the complete survey). This was done primarily to reflect the current methodology of the standard HCAHPS survey at our institution (mailing of surveys as soon as 48 h after discharge when the postoperative questions cannot be adequately answered). In the survey, questions 2 – 15 focus on preoperative visits with the surgeon, with a modification to skip these questions for patients who underwent an urgent or emergency operation. The data pertaining to the preoperative visits are not reported herein, because this data do not contain a summative item, and because a substantial proportion of patients undergoing non-elective surgery did not have a preoperative visit with the operating surgeon. Our previously published work has demonstrated a strong correlation between the preoperative and day of operation communication domains and overall surgeon rating.11 Further, we also examined responses from the standard HCAHPS survey for the subset of study patients who completed both surveys.

Patients were divided into groups for analysis based on how they responded to the global assessment of the surgeon. The question was as follows: “Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst surgeon possible and 10 is the best surgeon possible, what number would you use to rate all your care from this surgeon?” A response of 10 was considered the topbox response. Patients were placed in two groups, those who gave the topbox response and those who gave anything else (scores of 0–9). Standard H-CAHPS topbox scores for hospital evaluation include scores of 9 and 10 on this scale, but we chose to look only at scores of 10 on the S-CAHPS survey question to improve the discriminatory ability of the comparisons given the marked right skew in the data. Sensitivity analyses were performed with both 9 and 10 as the topbox outcome, and the results were similar to the findings presented here. This use of the Topbox definition is well established, both in the literature of health care surveys, as well as the understanding that Topbox definitions are fundamentally different than the other responses in the business literature.23 In addition, previous work has examined elements of patient satisfaction aa composite and continuous variables, and these trends related to determinants of satisfaction.24,25

Complication Definition

Complications were defined using the NSQIP definitions for postoperative complications 26. In addition, because some previous work suggested that major complications are associated with greater decreases in patient satisfaction with care 13, we constructed a group of major complications based on perceived clinical severity. Major complications were defined by the presence of: septic shock, cardiac arrest, stroke, ventilator > 48h, unplanned intubation, or organ space infection (Table 1). Retrospective chart review was undertaken to ascertain the presence of a postoperative complication.

Table 1:

Definitions of Major Complications

| Major Complication Definition |

|---|

| Septic Shock |

| Cardiac Arrest |

| Stroke |

| Ventilator > 48h |

| Unplanned Intubation |

| Organ Space Infection |

Variable definitions per NSQIP 2013 definitions:

Septic Shock: Definition: Sepsis is considered severe when it is associated with organ and/or circulatory dysfunction.

Cardiac Arrest: Definition: The absence of cardiac rhythm or presence of a chaotic cardiac rhythm requiring the initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Stroke: Definition: An interruption or severe reduction of blood supply to the brain resulting in severe dysfunction.

Ventilator > 48 h: Definition: Total cumulative time of ventilator-assisted respirations exceeding 48 h.

Unplanned Intubation: Definition: The placement of an endotracheal tube or other similar breathing tube [Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA), nasotracheal tube, etc.] and ventilator support.

Organ Space Infection: Definition: Organ/Space SSI is an infection that involves any part of the anatomy (e.g., organs or spaces), other than the incision, which was opened or manipulated during an operation

Cancer Operation Definition

Patients were considered to have undergone an operation for malignancy if the final pathology was consistent with a malignant neoplasm. This definition was chosen because we were interested in the patient satisfaction in the context of the most complete postoperative information for which to base their overall satisfaction. For example, if preoperatively the patient thought the surgical indication was for a benign disease, and the final pathology was consistent with a malignancy, the overall satisfaction with the surgeon could be impacted by the final pathology result (i.e. very happy that the malignancy was resected versus very upset that preoperative work up did not reveal a malignant process).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was generated using SPSS statistical software (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), with appropriate application of χ2 and t-tests for univariate analysis. Logistic regression was also generated using SPSS. Continuous variables are reported as mean +/− standard deviation.

RESULTS

1007 patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified, all of whom were sent surveys. The response rate was 54.5% (549/1007). Of the patients who responded to the survey, 20were excluded, because they either did not have an overnight stay or incorrectly identified the operating surgeon. Therefore, 529 patients were included in the final analytic sample. Of the included patients, only 16.8% (89/529) had also been sent the complete standard H-CAHPS survey, and therefore additional analysis of this survey in relation to the S-CAHPS is not included in this manuscript, but the strong correlation between the HCAHPS composite communication domain and S-CAHPS overall rating has been reported previously reported. 11The patients were 59.0% female with an average age of 58±16 years, and 95.5% self-identified as white, had a BMI of 30±8 kg/m2 and an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)27 class of 2.3±0.6, and had a duration of stay of 4.3±6.7 days; 26.8% (N=142) of patients underwent operation for malignancy, and 25.9% (N=137) underwent an urgent or emergency operation. The types of operations involved the gamut of general surgery services (Table 2) The overall NSQIP complication rate was 14.2% (75/529), with 26.7% (20/75) being major complications (Table 3).

Table 2:

Description of Surgical Procedures

| Surgical Procedure | Number |

|---|---|

| Colorectal (Malignant, Benign) |

142 (102,40) |

| Acute Care (Appendectomy) |

127 (51) |

| Endocrine | 61 |

| Bariatrics/Foregut | 60 |

| Gastrointestinal/Soft Tissue Oncology (exclusive of colorectal) |

50 |

| Breast | 46 |

| Other | 43 |

Table 3:

Summary of Major Complications

| Major Complication | Number |

|---|---|

| Deep Organ Space Infection | 11 |

| Septic Shock | 8 |

| Unplanned Intubation | 5 |

| Postoperative Ventilation >48 h | 4 |

| Postoperative MI | 1 |

| Postoperative Stroke | 0 |

Of note, patients could have more than one major complication. A total of 20 patients had a major complication.

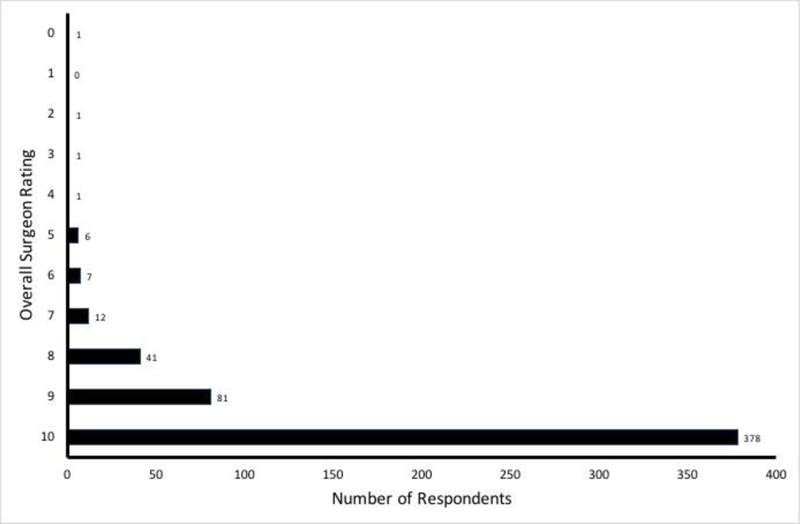

Of the patients included, 71.5% (378/529) of respondents rated the surgeon as topbox (an answer of 10 on the overall surgeon rating question), with the responses highly skewed to the higher ratings (Figure 1). When comparing the patients who rated the surgeon as the best possible with patients who rated the surgeon with lower rating, the patients’ BMI and ASA class were similar (Table 4).In contrast, patients who rated the surgeon as the best possible were older (59.1±17 vs. 53.7±17; p<0.001) and more likely to be female (64% vs. 48%; p=0.001)(Table 5). Additionally, the topbox surgeon ratings were associated with elective surgery (81% vs. 57%: p <0.001) and operations for malignancy (31% vs. 17%; p=0.001), but both the topbox and lower rated surgeons had similar durations of stay (Table 5).

Figure 1:

Distribution of Responses to Overall Surgeon Rating Question

Table 4:

Patient Demographics

| Variable | Highest Overall Surgeon – Topbox (n=378) |

Lower Overall Surgeon – Not Topbox (n=151) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; mean ±SD) |

59.1±16.6 | 53.7±16.6 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% female) | 64.0% | 47.7% | 0.001 |

| ASA Class (mean±SD) |

2.2±0.6 | 2.3±0.6 | 0.350 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 29.9±8.5 | 29.1±7.3 | 0.330 |

| Race (% White) |

ASA – American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status classification system; BMI – Body mass index, kg/m2; SD – Standard Deviation

Table 5:

Characteristics of Hospitalization and Postoperative Complications

| Variable | Highest Overall Surgeon – Topbox (n=378) |

Lower Overall Surgeon – Not Topbox (n=151) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent Procedure (% of group) |

19.0% (72/378) |

43.0% (65/151) |

<0.001 |

| Duration of stay (days; mean ±SD) |

4.3±8.2 | 4.3±6.0 | 0.976 |

| Operation for Malignancy (% of group) |

31.0% (117/378) |

16.6% (25/151) |

0.001 |

| Any NSQIP Complication |

15.3% (n=58) | 10.6% (n=16) | 0.168 |

| Major NSQIP Complications |

4.0% (n=15) | 3.3% (n=5) | 0.607 |

NSQIP – National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; SD – Standard Deviation

The rates of NSQIP-defined complications were similar between those who rated the surgeon as topbox and those who did not (15% vs. 11%; p=0.168)(Table 5). Additionally, there was no difference in the rate of major complications between the groups (4% vs. 3%; p=0.607). Multivariable logistic regression was performed including variables with p<0.1 on univariate analysis. Elective operation (p<0.001), increased age (p=0.004), and female sex(p=0.007) remained predictors of the higher rated surgeons (Table 6).

Table 6:

Logistic Regression Results

| Variable | Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

β-estimate | Wald χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older Age | 1.006 [1.01–1.03] |

0.018 | 8.09 | 0.004 |

| Female Sex | 1.745 [1.17–2.61] |

0.557 | 7.33 | 0.007 |

| Elective Operation | 2.515 [1.62–3.91] |

0.922 | 16.84 | <0.001 |

| Cancer Operation | 1.448 [0.86–2.43] |

0.370 | 1.98 | 0.160 |

A subset analysis of those who had a complication was performed to determine whether there was a temporal relationship between the complication and the return date of the survey on overall surgeon satisfaction. Fully 87.8% (65/74) of these patients experienced a complication prior to return of the survey. There was not a difference in overall surgeon satisfaction between those who experienced their complication prior to the return of the survey and those who experienced the complication after return of the survey (76.9% vs. 88.9%; p = 0.674 for the topbox surgeon rating for development of the complication prior to or after return of the survey).

Because our data relative to female sex differed from prior published experience 28, differences related to the sex of the patient were investigated further . When examining the proportion of elective operations by patient sex, there was a difference (80% vs. 66%, female vs. male; p<0.001). Further, females and elective operations were correlated (r=0.161; p<0.001). There was no difference in age of females vs. males (57.2±17 vs. 58.2±15; p=0.501). When performing multivariable logistic regression removing sex from the model (secondary to the high correlation with urgent operations), age and elective surgery remained associated with a more favorable surgeon rating (p=0.008 and p<0.001 respectively). Cancer surgery was not a statistically significant predictor (p=0.102). Taken as a whole, these observations suggest that difference in the percentage of elective surgery in the females in our sample at least explains in part the difference seen in surgeon satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated, using a large group of patients undergoing surgical procedures that there is no correlation between the NSQIP-defined postoperative complications and satisfaction with surgeon care as measured by the surgery specific S-CAHPS survey. Importantly, we examined this relationship at the level of the patient rather than at the institutional level as has been done in other recent reports 15–20,22. Additionally, previously identified variables important for satisfaction, namely elective admission and increased age, were important predictors of a higher overall rating of perceived surgeon care 4,8,13.

Given the importance of patient satisfaction data and its impact on reimbursement, there has been considerable interest in the relationship between satisfaction and more traditional outcome measures. In fact, CMS has suggested that public reporting of HCAHPS may improve clinical outcomes 29, but the results of published studies examining the relationship between satisfaction and clinical outcomes have been mixed 12. For example, Jha et al demonstrated a correlation between higher satisfaction and improved performance on Quality of Care Process Measures for the care of pneumonia and myocardial infarction when examined at the institutional level 15. These findings were later confirmed by Issac et al who expanded their measures to include the Patient Safety Indicators of the Hospital Quality Alliance and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the institutions evaluated 16. In contrast,, others failed to find any correlation between patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes 17–19.

The interest in the relationship between satisfaction and outcomes has been of interest in the surgical literature as well. Several studies have shown that patients with higher satisfaction also have improved outcomes 13,15,21. Specifically, Jha et al demonstrated that higher patient satisfaction was associated with increased Quality of Care Process Measures for surgery, including appropriate preoperative antibiotic administration and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism 15. Of particular interest was a similar study which examined the impact of postoperative complications on satisfaction at the patient level, but in patients undergoing a broader range of types of procedures 13. Danforth and colleagues examined generic HCAHPS survey results and although complication definitions were not standardized, they were graded using the Clavien-Dindo Scale 30. Interestingly, they found that postoperative complications, especially severe complications, are associated with dissatisfaction 13. In contrast, several other groups (in addition to our own) failed to find a strong correlation between satisfaction and postoperative complications 13,21,22,31. Two of these studies were limited in that they were conducted at the level of the institution 22,31 and used postoperative complications as determined by administrative datasets (a proxy known to have substantial limitations 32–34). A third study used NSQIP-defined complications but examined associations with satisfaction at the hospital-level 20;somewhat ironically, this study demonstrated an association between decreased satisfaction and minor complications, but this association did not hold for major complications. Finally, a fourth study conducted in patients undergoing orthopedic procedures demonstrated no correlation between satisfaction and postoperative complications at the patient-level 21.

The primary strengths of our study are the conduct of the analysis at the clinically relevant level (i.e. that of the individual patient), the use of a high-quality, standardized set of definitions for postoperative complications, and the use of the surgeon-specific satisfaction (S-CAHPS). But our study also has limitations. One limitation is the exclusion of the postoperative care questions on the S-CAHPS tool. Inclusion of the postoperative communication domains would have been ideal, however these were so highly correlated with those same domains preoperatively in the pilot data 35 that this is unlikely to have changed our findings. Further, surveying patients after a more delayed period to capture all of the postoperative follow up raises concerns about the potential for recall biases where other factors, other than their care of the surgeon, would have impacted their overall impression of their surgical experience. Another limitation is that the study was conducted at a single, tertiary care medical center, with a disproportionate number of Caucasian patients in our patient population secondary to the patient population of our institution. This consideration may very well limit the generalizability of our study, however, many of our findings are consistent with previous data, suggesting that this limitation is not likely skewing the results. Also, unfortunately we do not have demographic and complication data related to the non-responder group, however, previously published data including part of this data set demonstrated similarities between responders and non-responders, with slight differences in age and initial durations of stay.11 Our response rate of 55% s much better when compared with the most recent national response rate to HCAHPS of 28%36 and 33%37 over the study period, diminishing the impact of non-responder bias. Further, previous work has suggested that even though there is likely a non-responder bias, it is unlikely that response rates drive differences in satisfaction, at least on the hospital level.38 It would be ideal to be able to compare the results of the S-CAHPS with the hospital level HCAHPS, which includes domains not directly related to the clinical care or surgeon care (ex: hospital environment, nursing) care. Because the response rate for the HCAHPS survey is low, however, only a small fraction of patients completed both surveys. Additionally, we included patients undergoing urgent surgery, patients who were not included in the validation of the S-CAHPS tool. We chose to include them in the current study, because they represent a substantial proportion of patients at an academic medical center. Having a better understanding about the impact of an urgent operation on satisfaction is an important consideration for widespread use of this tool. In addition, we did not obtain the patient’s history of a previous operation, because the past surgical history in the chart is often incomplete (or impossible to obtain from the chart), and inclusion of this variable without a complete sample size could have resulted in an unreliable variable. Another limitation is the relatively small number of patients (n=549) when compared with previous studies, which used institutional datasets and conducted analyses not at the level of the patient, which could potentially introduce a Type II error.; however, this possibility is mitigated by ability to link satisfaction to clinical variables on the patient-level.

Given that we found no correlation between traditional NSQIP-defined outcomes and the S-CAHPS scores, our study b raises the question of how these findings should be used or interpreted. It is possible that the findings could be explained by patient factors, such as patient expectations or engagement in care distinct from their interactions with the surgeon. Previous data, however, have demonstrated clearly that the extent of physician communication is a strong correlate to overall surgeon rating.11 Another possible explanation for lack of correlation between complications and the S-CAHPS score is that strong communication mitigates the impact of complications on surgeon satisfaction, because communication appears the primary driver of overall surgeon rating.11 Previous work has demonstrated that a decrease in patient trust as a result of complications can be offset by effective communication.14 Ongoing work in this area is clearly needed to determine which factors, both patient and surgeon-related, are the primary determinants of satisfaction with surgical care.

Patient reported outcomes (PROs) are important, because they promote patient-centered care by improving shared decision-making and patient engagement.39 While true that patient satisfaction is one PRO, it is certainly not the only one relevant to the overall patient experience. Other more patient-centered, comprehensive PROs for perioperative patient experience are desperately needed. Some progress in this area has been made with the development and validation of the Surgical Recovery Score, but much work is needed to work toward a more summative tool that reflects patient experience in a more global fashion.40 The S-CAHPS does , however, appear to serve as a well-validated starting point to elucidate factors related to the patient experience. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has recognized the importance ofPROs and encourages the use of both clinical outcomes and PROs to improve overall patient care.41 To this end, we have been working both locally and more broadly to properly utilize patient experience scores in surgery. On an institutional level, the senior author (ERW) in her role as Medical Director for the Patient and Family Experience at UW Health has implemented multiple educational and training programs for students, trainees, and staff that focus on communication skills and relationship-based clinical care. The goal of these programs has been the improvement of the delivery of care, while emphasizing that these are outcomes although distinct from morbidity and mortality are still important. The specific focus of these sessions for surgical trainees came directly from our prior work in this area with the S-CAHPS tool.11 Regionally, we have shared our findings in this area in a comprehensive presentation regarding surgical complications and patient-reported outcomes with other academic centers. Those interactions have resulted in spreading our quality improvement initiatives and training opportunities to other surgical groups. Finally, and most specifically, we have been collaborating with the ACS to update the S-CAHPS tool by sharing our raw data from our surveys so that it could be combined with the data from several other research groups. The aim of that work is to improve the validity of the tool and to add to its generalizability, given that it is a relatively immature tool that is still being investigated and actively revised.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this patient-level analysis using NSQIP-defined postoperative complications and the surgery-specific S-CAHPS survey demonstrates no association between postoperative complications and patient satisfaction within surgical care. These findings suggest that satisfaction may be a distinct outcome to be considered along with traditional outcome measures. Further investigation into the primary determinants patient satisfaction with surgical care is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research Support: NIH T32 - 5T32CA090217-12

Wisconsin Surgical Outcomes Research Program (WiSOR)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Servces. The Official Website for the Medicare Hospital Value-based Purchasing Program http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/hospital-value-based-purchasing.

- 2.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Servces. Calculation of HCAHPS Scores: From Raw Data to Publicly Reported Results http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/HCAHPSFactSheetMay2012.pdf.

- 3.Hargraves JL, Wilson IB, Zaslavsky A, et al. Adjusting for patient characteristics when analyzing reports from patients about hospital care. Med Care 2001;39(6):635–641. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11404646. Accessed November 25, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen Thi PL, Briançon S, Empereur F, Guillemin F. Factors determining inpatient satisfaction with care. Soc Sci Med 2002;54(4):493–504. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953601000454. Accessed November 20, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoenfelder T, Klewer J, Kugler J. Factors associated with patient satisfaction in surgery: the role of patients’ perceptions of received care, visit characteristics, and demographic variables. J Surg Res 2010;164(1):e53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung CSK, Bower WF, Kwok SCB, van Hasselt CA. Contributors to surgical in-patient satisfaction--development and reliability of a targeted instrument. Asian J Surg 2009;32(3):143–150. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19656753. Accessed February 24, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavadas V, Barham CP, Finch-Jones MD, et al. Assessment of satisfaction with care after inpatient treatment for oesophageal and gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2004;91(6):719–723. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mira JJ, Tomás O, Virtudes-Pérez M, Nebot C, Rodríguez-Marín J. Predictors of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery 2009;145(5):536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sage J Using S-CAHPS. Bull Am Coll Surg 2013;98(8):53–56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24205576. Accessed February 24, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz KA, Rhee JS, Brereton JM, Zema CL, Witsell DL. Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems surgical care survey: benefits and challenges. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012;147(4):671–677. doi: 10.1177/0194599812452834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmocker RK, Cherney Stafford LM, Siy AB, Leverson GE, Winslow ER. Understanding the determinants of patient satisfaction with surgical care using the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems surgical care survey (S-CAHPS). Surgery July 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tevis SE K Schmocker RD Kennedy G Can patients reliably identify safe, high quality care? J Hosp Adm 2014;3(5):p150. doi: 10.5430/jha.v3n5p150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danforth RM, Pitt HA, Flanagan ME, Brewster BD, Brand EW, Frankel RM. Surgical inpatient satisfaction: What are the real drivers? Surgery 2014;156(2):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al. The effect of complications on the patient-surgeon relationship after colorectal cancer surgery. Surgery 2014;155(5):841–850. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med 2008;359(18):1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, Landon BE. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res 2010;45(4):1024–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01122.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, et al. Patients’ global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(9):665–672. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16670136 Accessed February 23, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao M, Clarke A, Sanderson C, Hammersley R. Patients’ own assessments of quality of primary care compared with objective records based measures of technical quality of care: cross sectional study. BMJ 2006;333(7557):19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38874.499167.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi TK, Francis EC, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Haas JS, Brennan TA. Inconsistent report cards: assessing the comparability of various measures of the quality of ambulatory care. Med Care 2002;40(2):155–165. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11802088. Accessed February 23, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sacks GD, Lawson EH, Dawes AJ, et al. Relationship Between Hospital Performance on a Patient Satisfaction Survey and Surgical Quality. JAMA Surg 2015;150(9):858–864. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day MS, Hutzler LH, Karia R, Vangsness K, Setia N, Bosco JA. Hospital-acquired conditions after orthopedic surgery do not affect patient satisfaction scores. J Healthc Qual 36(6):33–40. doi: 10.1111/jhq.12031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Girotti ME, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ. Patients’ perspectives of care and surgical outcomes in Michigan: an analysis using the CAHPS hospital survey. Ann Surg 2014;260(1):5–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reichheld FF, Teal T. The Loyalty Effect : The Hidden Force behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2001. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Loyalty_Effect.html?id=D-JlUoXtf-AC. Accessed March 16, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmocker RK, Holden SE, Vang X, et al. The number of inpatient consultations is negatively correlated with patient satisfaction in patients with prolonged hospital stays. Am J Surg December 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmocker RK, Holden SE, Vang X, Leverson GE, Cherney Stafford LM, Winslow ER. Association of Patient-Reported Readiness for Discharge and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems Patient Satisfaction Scores: A Retrospective Analysis. J Am Coll Surg September 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. User Guide for the Participant Use Data File Chicago; 2007. http://site.acsnsqip.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ACS-NSQIP-Participant-User-Data-File-User-Guide06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA Physical Status Classifcation System; 2014. http://www.asahq.org/~/media/sites/asahq/files/public/resources/standards-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system.pdf#search=%22asa classification%22.

- 28.Elliott MN, Lehrman WG, Beckett MK, Goldstein E, Hambarsoomian K, Giordano LA. Gender differences in patients’ perceptions of inpatient care. Health Serv Res 2012;47(4):1482–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Care quality information from the Consumer Perspective Hospital Survey http://www.hcahpsonline.org/home.aspx.

- 30.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P- A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240(2):205–213. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1360123&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed November 6, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy GD, Tevis SE, Kent KC. Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Ann Surg 2014;260(4):592–8; discussion 598–600. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasad A, Helder MR, Brown DA, Schaff H V. Understanding Differences in Administrative and Audited Patient Data in Cardiac Surgery: Comparison of the University HealthSystem Consortium and Society of Thoracic Surgeons Databases. J Am Coll Surg July 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.06.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koch CG, Li L, Hixson E, Tang A, Phillips S, Henderson JM. What Are the Real Rates of Postoperative Complications: Elucidating Inconsistencies Between Administrative and Clinical Data Sources. J Am Coll Surg 2012;214(5):798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters BD, Bharmal A, Wilson RF, et al. Validity of the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Hospital-acquired Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Care April 2016. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoy E Final CAHPS Submission Document-Surgical Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Services (Surgical CAHPS) Survey. Final Submission Document to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009.

- 36.Hospital Consumer Assessment of Helathcare Providers and Systems. Summary of HCAHPS Survey Results April 2016 to March 2017 Discharges http://www.hcahpsonline.org/globalassets/hcahps/summary-analyses/results/2017-12_summary-analyses_state-results.pdf.

- 37.Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Summary of HCAHPS Survey Results - October 2012 to September 2013 Discharges http://www.hcahpsonline.org/globalassets/hcahps/summary-analyses/summary-results/july-2014-public-report-october-2012---september-2013-discharges.pdf.

- 38.Saunders CL, Elliott MN, Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA. Do Differential Response Rates to Patient Surveys Between Organizations Lead to Unfair Performance Comparisons? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4674144/pdf/mlr-54-45.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff 2016;35(4):575–582. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paddison JS, Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Hill AG. Development and Validation of the Surgical Recovery Scale (SRS). J Surg Res 2011;167(2):e85–e91. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Pusic A, Temple L, Ko C. Patient-reported outcomes in surgery: Listening to patients improves quality of care | The Bulletin. Bull Am Coll Surg 2017;102(3):1–5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28920657. Accessed March 28, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]