Abstract

Background:

Serum concentrations of fatty acid binding proteins 4 (FABP4), an adipose tissue fatty acid chaperone, have been correlated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk factors. The objective of this study are to: (1) To assess relationships between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), intensive lifestyle modification and medical management protocol (LS/IMM), FABP4, and metabolic parameters in obese patients with severe type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). (2) To evaluate the relative contribution of abdominal subcutaneous adipose and visceral adipose to the secretion of FABP4.

Methods:

Subjects were randomized to LS/IMM (n = 29) or to LS/IMM augmented with RYGB (n = 34). Relationships between FABP4 versus demographics, metabolic parameters, and 12-month changes in these values were examined. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue explants from obese non-diabetic patients (n=5) were obtained and treated with forskolin to evaluate relative secretion of FABP4 in the different adipose tissue depots.

Results:

The LS/IMM and RYGB cohorts had similar fasting serum FABP4 concentrations at baseline. At one year, mean serum FABP4 decreased by 42% in RYGB subjects (P = 0.002), but did not change significantly in LS/IMM. Percent weight change was not a significant predictor of 12-month FABP4 within treatment arm or in multivariate models adjusted for treatment arm. In adipose tissue explants, FABP4 was secreted similarly between visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Conclusions:

Following RYGB, FABP4 is reduced 12 months after surgery but not after LS/IMM in patients with T2DM. FABP4 was secreted similarly between subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue explants.

Keywords: Bariatric Surgery, Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4, Metabolic Disease

TOC Statement- 20180445

Serum FABP4 is decreased after Roux-en Y gastric bypass in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. The importance of this finding is that FABP4, which correlates with cardiovascular risk, may provide insight to the benefits of bariatric surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are significant sources of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and are increasing at epidemic rates 1. For decades, bariatric surgery has been the most effective treatment for obesity, and more recently has been recognized for its value in the treatment of T2DM. Previously published results from the Diabetes Surgery Study (DSS) have shown that augmenting lifestyle modification and intensive medical management (LS/IMM) with RYGB increases weight loss and improvements in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with severe T2DM and BMI 30.0–39.9 2 Other studies have corroborated these observations 3.

Currently, less than 1% of the population with obesity and T2DM that meet Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) criteria for surgical intervention undergo surgery given its cost, invasiveness and patient suitability requirements 4,5 Identifying mechanisms responsible for the efficacy of surgery may allow us to improve non-surgical care for patients with T2DM. Proposed mechanistic explanations underlying the effectiveness of bariatric surgery include changes in bile acids, increases in glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 secretion, and shifts toward more metabolically favorable intestinal microbiota, among others 6–9 However, adipose tissue dysfunction, a central feature of insulin resistance, remains inadequately characterized.

Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4, also known as aP2) is a 15 kDa lipid carrier that is abundantly expressed in adipose tissue, and plays a major role as a fatty acid chaperone facilitating lipolysis and additionally is secreted into circulation 10. In mice fed a high saturated fat diet, deletion of FABP4 reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity without altering weight, thus uncoupling insulin resistance from obesity 11—13. FABP4 has primarily been investigated as a cytosolic protein, and we have previously observed a rapid reduction in the mRNA and protein levels of FABP4 in subcutaneous adipose tissue following bariatric surgery 14.

Although primarily investigated as a cytosolic protein, several studies have shown associations between higher serum FABP4 and a number of diseases 19–22. The Framingham Heart Study found that higher circulating FABP4 is positively correlated with insulin resistance and multiple cardiovascular risk factors, including total cholesterol, lower HDL, and hypertension 22. Circulating FABP4 is known to be elevated in patients with obesity and has been identified as a predictor of the development of metabolic syndrome independent from adiposity and insulin resistance 23. Furthermore, a polymorphism in the promoter region of FABP4 that results in decreased expression is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease and development of T2DM in subjects with obesity 24. Even cancer outcomes, including morbidity and mortality in breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers, have been associated with higher serum FABP4 concentrations 25–27. However, the secretion of FABP4 remains poorly understood. It remains unclear which adipose depot, i.e. visceral versus subcutaneous, contributes to its secretion.

While both depots have been shown to be independent contributors to cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome and play active endocrine roles, there are important physiologic differences including adipokine secretion, and rates of lipolysis and triglyceride synthesis 15–17. In fact, many diseases that affect fat, i.e. glucocorticoid excess and congenital lipodystrophy, do so in a depot specific manner 18. Although FABP4 appears to be linked to a number of diseases, studies identifying a direct relationship between FABP4 and weight change are limited, but it appears that it may also serve as a prognostic marker for weight loss 28. Given its known biology, it would be expected that FABP4 concentrations increase with rapid weight loss due to an increase in lipolysis and fatty acid transport, but long-term reductions in weight would result in its reduction 29.

While causality has not been established, the association between more favorable metabolic parameters and lower FABP4 concentrations suggests that achieving reductions in FABP4 may be of value in treating metabolic syndrome. One intervention to accomplish this may be bariatric surgery. While serum FABP4 concentrations have been observed to decrease following RYGB, it is unclear how this decrease is related to weight loss and glucose homeostasis. It is also unclear how current medical management of obesity and T2DM affects serum FABP4 concentrations 30,31. In this study, we measure serum FABP4 in a pilot cohort of subjects with T2DM, HbA1c > 8.0% and BMI 30.0–39.9 at baseline. Subjects were randomized to LS/IMM with or without RYGB. FABP4, BMI and metabolic parameters were measured at baseline and at one year post-intervention; in this ancillary study we explore potential relationships between FABP4 and the other values, both within and between treatment arms. To identify the major adipose depot contributing to serum concentrations of FABP4, we then utilized visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue explants from obese patients at the time of bariatric surgery and assessed the relative contribution of each depot to circulating FABP4 level.

METHODS

Subjects

The Diabetes Surgery Study was a randomized trial comparing the effectiveness of RYGB and LS/IMM to achieve established therapeutic targets for the treatment of T2DM. Details of subject recruitment and randomization have been previously reported 2,8,32. All institutions involved had Institutional Review Board approval. Between 2008 and 2011, 60 of the 120 obese subjects participating in an intensive lifestyle and medically managed weight control program were randomized to undergo RYGB while continuing a lifestyle/medical management protocol. Inclusion criteria included age >30, BMI of 30.0–39.9 kg/m2, undergoing treatment for T2DM for at least 6 months, HbA1c of 8.0% or higher, and C-peptide > 1.0 ng/ml 90 minutes after a liquid mixed meal. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had serious conditions precluding surgery. The lifestyle intervention was modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Look AHEAD protocol 33,34 Subjects met regularly with a trained bariatric registered dietician. Lifestyle interventions were augmented with intensive medical therapy to obtain treatment goals established by American Diabetes Association: HbA1c < 7.0%; serum LDL cholesterol < 100 mg/dL; and systolic blood pressure < 130 mmHg. Techniques for the RYGB have been previously published 2.

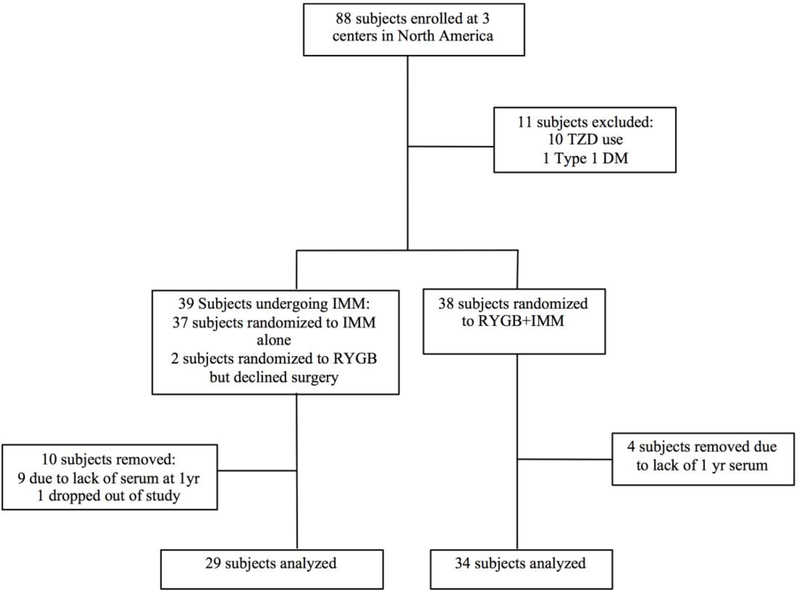

Candidates for the current analysis were selected from among the 88 DSS subjects randomized at three clinics in the United States (University of Minnesota, Columbia University in New York, and Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN) (Figure 1). Subjects were excluded if they lacked follow-up data or available sera at 12 months, if they were type 1 diabetics, if they used thiazolidinediones (TZDs) at baseline or during the first year of the clinical trial, or if they crossed over after the study was underway. Subjects on TZDs were excluded from the current analysis because TZDs are known to increase the activity of the nuclear receptor responsible for FABP4 expression 20. Subjects recruited for the evaluation of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue provided informed consent approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Tissue biopsies were obtained from these subjects at the time of bariatric surgery.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Measurement and data collection

Data were collected at baseline and at scheduled medical visits. Collected data included height, weight, medications used, and laboratory measurements including HbA1c, fasting and 90- minutes post meal glucose, and C-peptide concentrations. Serum FABP4 was measured with human FABP4 Quantikine ELISA kit from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN; #DFBP40) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical design and analysis

Baseline characteristics and one-year outcomes for this cohort were reported using means (95% CI or ± standard deviation) for continuous data and percentages for categorical data.

Comparisons were made using Student’s T-test, chi-squared statistics, and exact binomial models where appropriate. Univariate linear regressions were used to analyze variables potentially associated with serum FABP4, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, time since diagnosis of T2DM, BMI, % weight change, HbA1c, post-challenge C-peptide, fasting and postchallenge glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, Matsuda Index [calculated as 10,000/(glucose0 X insulin0 X mean glucose X mean insulin)0.5], and use of exogenous insulin, other antihyperglycemics, or statins 8. Variables with p values < 0.15 in univariate regression analyses were considered in developing optimal multivariate models. As this is an exploratory analysis, many hypothesis tests were carried out without prior hypotheses specified, thus no adjustments for multiple comparisons were imposed. Univariate models were used to identify determinants of 12-month levels of FABP4, and then used to construct a multivariate model for prediction of FABP4 at 12 months. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) Assay

Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue explants were collected from human subjects. 50mg of tissue samples were used to measure free fatty acid (FFA) release. The explants were treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle control or 20μM forskolin (Fsk) for 1 and 4 hours. NEFA assay of tissue explants were performed as described35 and measured using NEFA-HR kit (Wako, Richmond, VA).

Immunoblot

The tissues were incubated in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer with 1% BSA. The incubating media/extracellular material was collected for further analysis. The tissue explants were homogenized on ice in a homogenization buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl and 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1mM NaP2O7, 50mM NaF supplemented with protease inhibitors (Calbiochem, Billerica, MA)). Homogenates were centrifuged at 1000g at 4° C for 10 min to separate the lipid cake, the infranatant was removed and sodium dodecyl sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1%. The lysate was then centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 mins at 4 °C to remove insoluble residue and the supernatant recovered. Western blot analyses were performed on equal volumes of incubating media from all samples and 5% of tissue lysate and incubating media to detect FABP4 and intracellular protein beta actin. FABP4 was assayed by running calculated amounts of purified FABP4 protein samples on respective gels. The immunoblots were imaged using Odyssey infrared imaging (Li-Cor Biosciences; Lincoln, NE). The antibodies used were anti-FABP4 and anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Of the 88 possible candidates for review, 25 were excluded: 13 for absent serum samples, 10 due to TZD use at baseline, one who was later diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, and one patient randomized to LS/IMM patient who later obtained surgery outside of the study. Two subjects who declined surgery after randomization but participated in the LS/IMM intervention were grouped with the LS/IMM cohort for the current as-treated analysis. The resulting 29 LS/IMM and 34 surgery subjects are included in the study (Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between groups. Mean age was 51; mean BMI was 36 kg/m2; mean HbA1c was 9.5%; and mean circulating FABP4 was 38 ng/ml. Years since diabetes diagnosis and use of insulin were not different between groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects randomized to LS/IMM or RYGB. Values are reported as mean ± Standard Deviation or n (%).

| LS/IMM (n=29) | RYGB (n=34) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||

| Age (years) | 50 ± 8 | 51± 9 | 0.60 |

| Female | 13 (45%) | 22 (65%) | 0.13 |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.00 | ||

| Black or African | 4 (14%) | 5 (15%) | |

| American | |||

| Native American | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (7%) | 2(6%) | |

| GENERAL | |||

| MEDICAL | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.7 ± 3.2 | 36.1 ± 2.7 | 0.60 |

| Years Since Diabetes | 8.9 ± 5.7 | 11.1 ± 6.4 | 0.14 |

| Diagnosis LABORATORY VALUES |

|||

| HbA1c (%) | 9.5 ± 1.2 | 9.5 ± 0.9 | 0.97 |

| Circulating FABP4 (ng/ml) | 38 ± 17 | 38 ± 22 | 0.92 |

| C peptide, 90-minute (ng/ml) | 5.1 ± 2.6 | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 0.13 |

| Glucose, fasting (mg/dL) | 215 ± 58 | 224 ± 65 | 0.48 |

| Glucose, 90-minute (mg/dL) | 273 ± 64 | 284 ± 55 | 0.47 |

| Insulin, fasting (mU/L) | 22 ± 19 | 27 ± 30 | 0.46 |

| HOMA-IR | 11.5 ± 12.1 | 13.7 ± 13.5 | 0.50 |

| Matsuda Index | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 2.5 ± 2.5 | 0.63 |

| TAKING MEDICATION (YES/NO) |

|||

| Insulin | 15 (52%) | 26 | 0.11 |

| Oral Anti-Hyperglycemic | 28 (97%) | 28 (80%) | 0.06 |

| Any Anti-hyperglycemic | 29 (100%) | 34 (100%) | 1.00 |

| Statin | 19 (66%) | 24 (69%) | 1.00 |

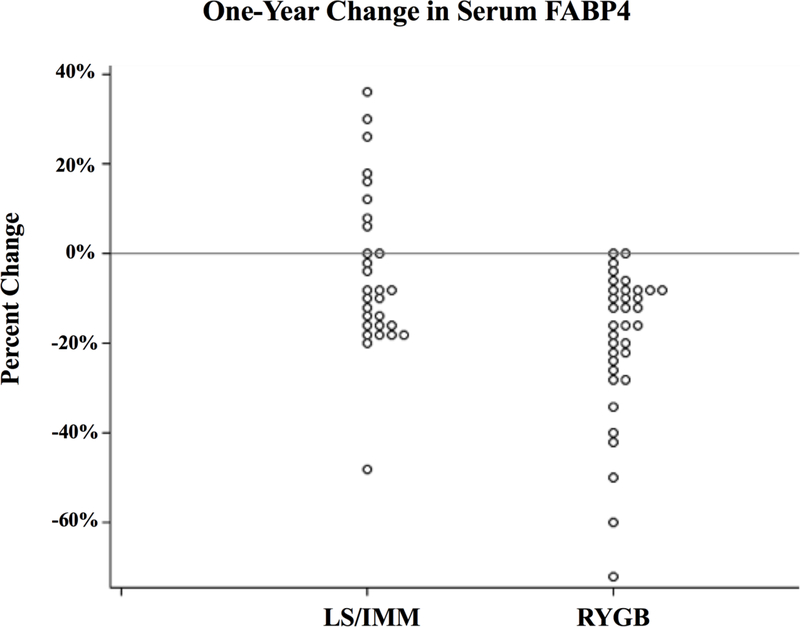

One-year outcomes are consistent with previous DSS analyses 2,8,3,6. Compared to LS/IMM, RYGB subjects had significantly greater weight loss and improved glycemic control despite less medication. (Table 2). At one year, circulating FABP4 was 19 ng/ml (95% CI 15 to 23) in RYGB subjects versus 33 ng/ml (26 to 40) in LS/IMM subjects (42% lower; p=0.002). Mean FABP4 dropped 50% in the surgery group, with a proportionate reduction in variability. FABP4 decreased in all but two RYGB subjects, whose concentration did not change. In contrast, in the LS/IMM group, mean FABP4 decreased 13% but was accompanied by an 11% increase in variability; 10 of 29 (34%) of LS/IMM subjects exhibited either increased concentrations or no change (Figure 2). In the LS/IMM cohort, no factors (BMI, HbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin) differed significantly between subjects who had increased serum FABP4 concentrations compared to those who had decreased concentrations.

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects one year after the intervention began. Values are reported as mean (95% CI) or n (%).

| LS/IMM (n=29) | RYGB (n=34) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.2 (30.6,33.7) | 25.8 (24.6,26.9) | <.00001 |

| Weight Change > (Percent of baseline) | -10 (-13, -7%) | -29 (-31, -26) | <.00001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.1 (6.7, 7.6) | 6.3 (6.0, 6.7) | 0.01 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 14 (48%) | 25 (74%) | 0.07 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% with no medication | 0 (0%) | 19 (56%) | <.00001 |

| Circulating FABP4 (ng/mL) | 33 (26, 40) | 19 (15, 23) | 0.002 |

| C peptide, 90-minute (ng/ml) | 5.9 (4.8, 7.0) | 3.9 (3.3, 4.4) | 0.002 |

| Glucose, fasting (mg/dL) | 139 (123, 156) | 108 (99, 118) | 0.003 |

| Glucose, 90-minute (mg/dL) | 180 (156, 205) | 129 (116, 142) | 0.001 |

| Insulin, fasting (mU/L) | 16 (10, 21) | 7 (3, 10) | 0.01 |

| HOMA-IR | 5.8 (3.2, 8.4) | 1.9 (0.8, 3.0) | 0.01 |

| Matsuda Index | 6.0 (3.8, 8.1) | 9.3 (7.1,11.4) | 0.04 |

| TAKING MEDICATION (YES/NO) |

|||

| Insulin | 13 (45%) | 8 (24%) | 0.11 |

| Oral | 29 (100%) | 13 (38%) | <.00001 |

| Antihyperglycemic Any | 29 (100%) | 14 (41%) | <.00001 |

| Antihyperglycemic Statin | 21 (72%) | 17 (50%) | 0.08 |

Figure 2.

One year percent change in serum FABP4 concentrations in subjects following

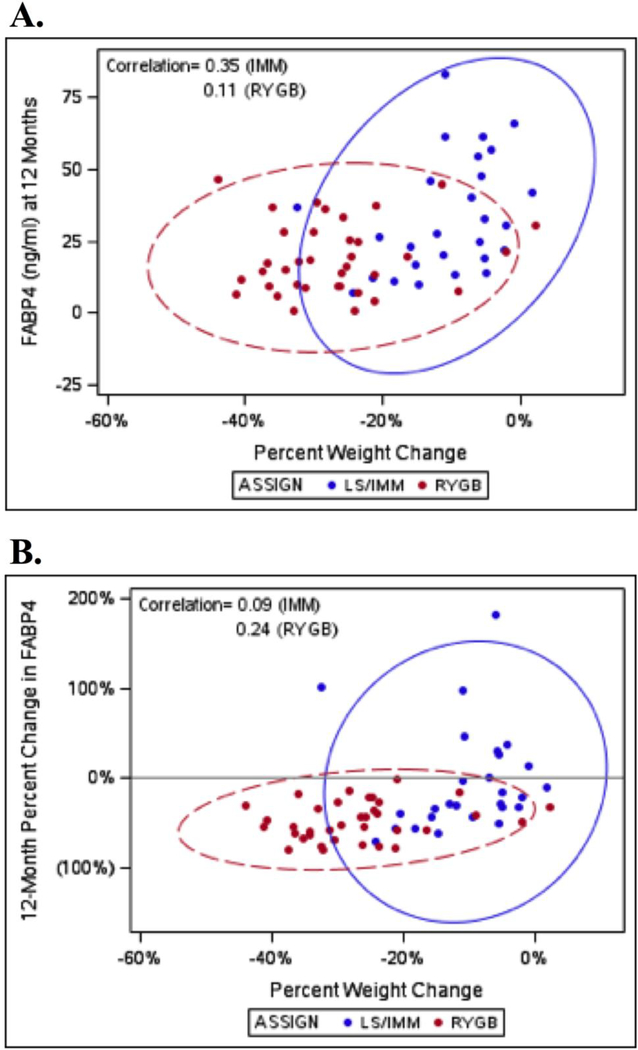

Within treatment arm, percent weight change and 12-month FABP4 were weakly associated in LS/IMM (correlation 0.35; p=0.07), but not in RYGB (correlation 0.11; p=0.52) (Figure 3). After adjustment for baseline FABP4, percent weight change was not a significant predictor of 12-month FABP4 in either arm. In the IMM arm, a 10% greater weight loss corresponded to 5.20 ng/ml lower FABP4 in the IMM group (95% CI -3.96 to 14.36; p-value = 0.25; R2 = 0.34). In the surgical arm, a 10% greater weight loss was associated with 2.12 ng/ml lower FAPB4 (95% CI -1.12 to 5.37; p=0.19; R2=0.44). Both cohorts include patients with 0– 20% weight loss; while everyone lost weight following RYGB, not everyone lost weight in the IMM cohort. FABP4 is much more variable for the IMM patients in this range than for the RYGB patients.

Figure 3.

Predictive ellipses of serum FABP4 versus percent weight change. (A) Crosssectional 12-month FABP4. (B) 12-month percent change in FABP4.

In further exploratory analyses, we examined 15 baseline characteristics as potential univariate predictors of baseline FABP4 (Table 3). Significant associations included age (7.4 ng/ml higher FABP4 per 10-year greater age; 95% CI 1.5 to 13.2), female sex (13.4 ng/ml higher FABP4; 95% CI 3.9 to 22.8), fasting glucose (1.1 lower ng/ml FABP4 per 10 mg/dl higher fasting glucose; 95% CI 0.3 to 1.9), and 90-minute post-challenge glucose (0.8 ng/ml lower FABP4 per 10 mg/ml higher glucose; 95% CI 0 to 1.6; p = 0.05).

Table 3.

Baseline variables as univariate predictors of a 1 ng/ml increase baseline FAPB4. (Analysis based on all study subjects).

| Estimate (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Age (per 10 years) | 7.4 (1.5, 13.2) | 0.01 |

| Female | 13.36 (3.91, 22.80) | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity GENERAL MEDICAL | 0.18 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | -0.41 (-2. 14, 1.31) | 0.63 |

| Years Since Diabetes Diagnosis LABORATORY VALUES | 0.00 (-0.82, 0.82) | 1.00 |

| HbA1c (%) | -1.68 (-6. 59, 3.24) | 0.50 |

| C peptide, 90-minute (ng/ml) | -0.79 (-3.04, 1.46) | 0.48 |

| Glucose, fasting (per 10 mg/dL) | -1.1 (-1.9, -0.3) | 0.01 |

| Glucose, 90-minute (per 10 mg/dL) | -0.8 (-1.6, 0.00) | 0.05 |

| Insulin, fasting (mU/L) | -0.08 (-0.28, 0.12) | 0.42 |

| HOMA-IR Matsuda Index | -0.27 (-0.66, 0.12) | 0.17 |

| TAKING MEDICATION (YES/NO) | 0.78 (-1.54, 3.09) | 0.50 |

| Insulin | 2.56 (-7.79, 12.90) | 0.62 |

| Oral Anti-hyperglycemic | -0.16 (-15.2, 14.84) | 0.98 |

| Any Anti-hyperglycemic | -- | -- |

| Statin | 2.91 (-7.65, 13.47) | 0.58 |

Similarly, individual patient characteristics (including baseline, 12-month, and 12-month change, where appropriate) were examined individually as predictors of 12-month FABP4 (Table 4). Regressions were conducted separately by treatment arm and adjusted for baseline FABP4. At 12 months, percent weight change dominated treatment arm as a predictor of HbA1c, as previously reported 2 However, percent weight change was not a significant predictor of 12-month FABP4 within either treatment arm, either after adjustment for baseline FABP4 or in potential multivariate models. Similarly, no other baseline value was predictive of 12-month FABP4 after adjustment for baseline FABP4. In the LS/IMM group, the optimal multivariate model for 12-month FABP4 included baseline FABP4, change in fasting insulin, and change in post-challenge C-peptide. In the RYGB group, the optimal model included only baseline FABP4. R2, the proportion of variability explained by the model, was 0.50 in the optimal LS/IMM model and 0.41 in the optimal RYGB model.

Table 4.

Predictors of 1 ng/ml greater FABP4 at 12 months by treatment arm.

| Predictors of FABP4 at 12 Months By Treatment Arm* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMM | RYGB | |||

| Estimate (95% CI) | P- value | Estimate (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Baseline FABP4, as a univariate predictor Individual Predictors adjusted for baseline FABP4: | 0.63 (0.24, 1.03) | 0.003 | 0.37 (0.22, 0.53) | <.0001 |

| At 12 months: | ||||

| HbA1c (%) | 3.36 (-2.08, 8.8) | 0.24 | 3 (-0.31, 6.31) | 0.09 |

| Glucose, fasting (mg/ml) | -0.01 (-0.16, 0.13) | 0.88 | 0.12 (0.01, 0.24) | 0.04 |

| Insulin, fasting (mU/L) | 0.37 (-0.06, 0.8) | 0.10 | 0.1 (-0.2, 0.41) | 0.51 |

| Change from baseline to 12 months: | ||||

| Percent Weight Change (per 10%) | 51.98 (-35, 138.95) | 0.25 | 21.25 (-10, 52.5) | 0.19 |

| HbA1c (%) | 2.78 (-1.75, 7.31) | 0.24 | 2.14 (-0.43, 4.71) | 0.11 |

| C peptide, 90-minute (ng/ml) | -2.88 (-6.5, 0.74) | 0.13 | 0.5 (-1.16, 2.17) | 0.56 |

| Glucose, fasting (per 10 mg/dL) | 0.1 (-1.1, 1.3) | 0.87 | 0.4 (-0.1, 0.9) | 0.11 |

| Glucose, 90-minute (per 10 mg/dL) | 0.0 (-1.0, 1.1) | 0.94 | 0.4 (-0.1, 0.8) | 0.11 |

| Insulin, fasting (mU/L) | 0.32 (0.01, 0.63) | 0.05 | -0.01 (-0.13, 0.11) | 0.87 |

| Optimal multivariate model:** | ||||

| FABP4 at baseline (ng/ml) | 0.44 (0.06, 0.82) | 0.03 | 0.37 (0.22, 0.53) | <.0001 |

| Change in fasting insulin (mU/L) | 0.36 (0.05, 0.67) | 0.02 | ||

| Change in 90-minute C-peptide (ng/ml) | -3.4 (-6.92, 0.11) | 0.06 | ||

The following potential predictors were also considered: age, gender, years since diabetes diagnosis, BMI, use of insulin, other anti-hypoglycemic medications or statins, and BMI. Only percent weight change and predictors with p<0.15 after adjustment for baseline FABP4 are shown above.

R2 for the optimal multivariate models was 0.50 (IMM) and 0.41 (RYGB).

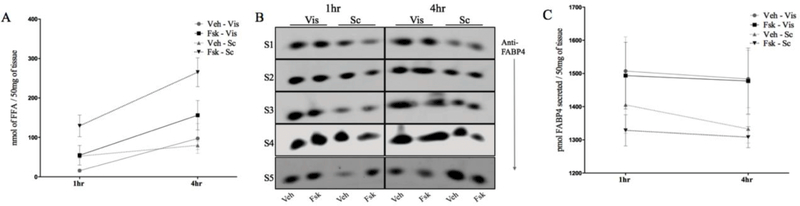

Next, we utilized visceral and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue explants obtained from obese human subjects undergoing bariatric surgery to identify the relative contributions of these depots to the secretion of FABP4 (Supplemental Table 1). The ex-vivo tissue explants effluxed non-esterified free fatty acids and responded to lipolytic stimuli (Figure 4A), indicating that the tissues were metabolically active. To analyze the secretory capacity of visceral and abdominal subcutaneous depots, we measured the FABP4 secreted from excised samples. The two types of adipose samples secreted similar amounts of FABP4 (p=0.47 and p=0.17, 1 and 4 hours following DMSO treatment, respectively; Figure 4B, C). Intriguingly, the secretion of FABP4 was not stimulated in response to lipolytic signal from human tissue (p= 0.19 and p=0.17, 1 hour and 4 hours following FSK treatment, respectively). To confirm that the FABP4 in the supernatant was secreted and not present in media due to tissue cellular lysis, we evaluated the expression of β-actin in both intracellular and extracellular material. The presence of actin in the cellular lysate but not in the cell culture supernatant fraction is an indicator of intact cells and implies that FABP4 found is the secreted fraction resulting from regulated release rather than lytic release.

Figure 4.

FABP4 is secreted from both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues. (A) Adipose tissue explants from either the visceral (Vis) or subcutaneous (Sc) depot were treated with DMSO or forskolin (FSK) for 1 to 4 hours and non-esterified free fatty acids (FFA) released into the incubation medium determined. (B) Immunoblot of FABP4 secreted from tissue explants from human subjects (S1-S5) in response to DMSO or FSK treatment. (C) Quantitation of FABP4 secreted into the incubating media. (D) Immunoblot of ßactin from tissue lysates and incubation media of DMSO and FSK-treated tissue explants.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed serum FABP4 concentrations in a diabetic population one year after randomization to LS/IMM with or without RYGB. Mean serum FAPB4 decreased 50% in the year following surgery, versus a one-year decrease of just 13% in LS/IMM. Furthermore, no statistically significant correlation was identified between weight loss and 12-month FABP4 levels in either arm. In evaluating the relative contribution of the secretion of FABP4 from visceral and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue, both depots secrete approximately similar amounts of FABP4/mg tissue suggesting that the majority of serum FABP4 is attributable to subcutaneous adipose tissue given its larger volume.

Our observations are consistent with findings from others showing reductions in serum FABP4 concentrations at 6 and 12 months following RYGB 30,31. However, this current study describes subjects with severe T2DM, whereas the previous cohorts were predominantly non-diabetic. It thus appears that RYGB is associated with significant one-year reductions in serum FABP4, regardless of diabetic status. The reduction of serum concentration of FABP4 may contribute to improved metabolism following RYGB. Numerous animal studies and evaluations of human polymorphisms link FABP4 to insulin resistance, increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increased reactive oxygen species 10,24,12,38. Higher serum FABP4 is associated with higher BMI and worsened dyslipidemia 22,39. Elevated FABP4 is also linked to hepatic insulin resistance and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis. Furthermore, a genetic polymorphism that decreases FABP4 expression appears to have a protective effect against T2DM and atherosclerosis when controlled for BMI 24. While causal pathways have yet to be determined, clinical treatments that reduce serum FABP4 might be beneficial for patients with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes. Animal studies targeting the reduction of FABP4 using monoclonal antibodies have been promising 40 RYGB is currently the only known treatment that reliably significantly decreases this adipokine, although angiotensin II receptor blockers, atorvastatin and omega-3 fatty acids have shown modest reductions 41–43.

While others have observed a positive correlation between FABP4 concentrations and HOMAIR following RYGB 30, in our exploratory analysis we did not observe the same association. We did, however, observe a weak negative association between fasting glucose levels and serum FABP4 concentrations at baseline. In the LS/IMM cohort, change in fasting insulin was included in the optimal multivariate model predicting 12-month FABP4. Reasons for these differences are unclear, but may be related to medication use, extent of weight loss, and diabetic status. Further in-depth metabolic studies are needed to elucidate these relationships. Greater age and female gender were both also associated with higher baseline FABP4. Factors accounting for gender differences include androgen hormone production and body composition 44.

It is not clear how FABP4 concentrations decline following RYGB. A gene target of the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, FABP4 is the major lipid chaperone in adipocytes, facilitates lipolysis, and is secreted into serum by unconventional means 45,46. Sustained reductions in serum FABP4 at one year following RYGB may be due to alterations in adipose tissue metabolism that are specific to RYGB. This reduction may be mediated by the effect of RYGB on other serum factors, like GLP-1 which is increased after RYGB 89.

Sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor that increases GLP-1, results in mild reductions of FABP4 concentrations in patients with T2DM 47. It is possible that RYGB with significant weight loss itself contributes to reductions in FABP4 in the long-term, but how this may occur is also unclear. Long-term studies of FABP4 in medically managed weight loss cohorts after two years of treatment have shown reductions in FABP4 48. Baseline FABP4 has even been proposed as a prognostic factor for maintenance of weight loss after a calorically restricted medical intervention 28. However, these assessments were made in insulin sensitive populations. FABP4 lacks a conventional secretion signal sequence, and thus utilizes an unconventional secretion mechanism. Molecular details describing this secretion have been limited.

Importantly, the underlying concept of how different adipose depots contribute to circulating FABP4 is yet unexplored. Analyzing the relative contribution of FABP4 secretion from visceral and abdominal subcutaneous depots provides an insight to the relationship of body composition to whole-body FABP4 secretion. Our findings here indicate that both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues secrete FABP4. An intriguing finding however, is that FABP4 secretion was not potentiated in response to lipolytic stimuli, in contrast with studies in mice wherein beta adrenergic signaling stimulated FABP4 secretion (37). This observation suggests that the subcutaneous depot may be the major contributor to serum concentrations of FABP4 because of its significantly larger volume. Likewise, a substantial loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue following surgery is likely to contribute to reductions in FAPB4 concentrations. However, more studies are needed to confirm our initial observations.

There are limitations of this study that should be highlighted. RYGB subjects had greater weight loss than medical management (mean=29% versus 10% in LS/IMM); the study would be strengthened by weight loss-matched cohorts. Effects of recent weight loss may confound the relationship between adipose tissue and serum FABP4. If the apparent differences in FABP4 metabolism are related to RYGB per se, RYGB subjects may be compared with another form of bariatric surgery (for instance banding or sleeve gastrectomy). Other potential confounders include medication use at baseline and differences in medication use at 12 months as well possible changes in dietary fat intake, which has been shown to alter the expression of FABP4 in adipose tissue 49 This study is also limited by the variability in the changes in FABP4 concentrations following each intervention, and could be strengthened by a larger sample size. In contrast to the DSS patients providing longitudinal lab data, patients providing adipose tissue samples were insulin sensitive and were not taking any antidiabetic medications. The contrast weakens the study, but on the other hand lack of medication use in the patients providing tissue samples may limit confounding. This study would also be strengthened by the evaluation of visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots at additional sites, as well as in a larger study population. Future studies would include evaluating changes in patients who are prediabetic or diabetic off medications, as well as measurements of FABP4 in shorter time intervals following surgical or medical intervention to elucidate potential relationships with weight change. Another cohort of patients to study would be those undergoing abdominoplasty, which would provide further insight into the relative contribution of subcutaneous adipose tissue to serum concentrations of FABP4. An important strength of this study is its reliance on data from a randomized clinical trial, eliminating confounding due to self-selection.

In conclusion, in a randomized cohort of subjects with BMI 30.0–39.9 and severe T2DM, FABP4 levels decreased markedly 12 months after RYGB. No statistically significant reduction in FABP4 was observed 12 months exposure to an intensive lifestyle and medical management protocol. This study also failed to demonstrate a relationship between weight loss and reductions in FABP4. Further in-depth metabolic studies are required to characterize the relationship between serum FABP4 concentrations and tissue specific insulin resistance, and to understand how RYGB contributes to the marked decline in FAPB4.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank study coordinators Joyce Schone, RD and Nyra Wimmergren, RN, at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN), and Heather Bainbridge, RD, CDN, at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY. We would also like to thank members of the Bernlohr lab for their technical support and contributions to the manuscript. This work was funded in part by Covidien/Medtronic and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001873.

Funding

The Diabetes Surgery Study (DSS) was supported by Covidien, Mansfield, MA. This study was also supported in part by an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award through its Center for Advancing Translations Sciences, Grant No. UL1 TR001873 NIH DK053189.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CLL, Carroll MDD, Kit BKK, Flegal KMM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Jama. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee W- J, et al. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass versus Intensive Medical Management for the Control of Type 2 Diabetes, Hypertension and Hyperlipidemia: An International, Multicenter, Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2012;309(21):2240–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.07.002.Identification. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric Surgery versus Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes - 3-Year Outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westerveld D, Yang D. Through Thick and Thin: Identifying Barriers to Bariatric Surgery, Weight Loss Maintenance, and Tailoring Obesity Treatment for the Future. Surg Res Pract 2016;2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/8616581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitzul KB, Jackson T, Crawford S, et al. Understanding disposition after referral for bariatric surgery: When and why patients referred do not undergo surgery. Obes Surg 2014;24(1):134– 140. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jahansouz C, Xu H, Hertzel A, et al. Bile Acids Increase Independently From Hypocaloric Restriction After Bariatric Surgery. Ann Surg 2016;264(6):1022–1028. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liou AP, Paziuk M, Luevano J- M, Machineni S, Turnbaugh PJ, Kaplan LM. Conserved shifts in the gut microbiota due to gastric bypass reduce host weight and adiposity. Sci Transl Med 2013;5(178):178ra41. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen KT, Billington CJ, Vella A, et al. Preserved Insulin Secretory Capacity and Weight Loss Are the Predominant Predictors of Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Randomized to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Diabetes. 2015;64(April):3104–3110. doi: 10.2337/db14-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachdev S, Wang Q, Billington C, et al. FGF 19 and Bile Acids Increase Following Roux-en- Y Gastric Bypass but Not After Medical Management in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Obes Surg. 2016;26(5):957–965. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1834-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotamisligil GS, Bernlohr DA. Metabolic functions of FABPs—mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(10):592–605. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuhashi M HG. Fatty acid-binding proteins: role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010;7(6):489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrd2589.Fatty. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hotamisligil GS, Johnson RS, Distel RJ, Ellis R, Papaioannou E, Spiegelman BM. Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science (80-). 1996;274(5291):1377–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbay E, Babaev VR, Mayers JR, et al. Reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress through a macrophage lipid chaperone alleviates atherosclerosis. 2010;15(12):1383–1391. doi: 10.1038/nm.2067.Reducing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahansouz C, Xu H, Hertzel AV, et al. Partitioning of adipose lipid metabolism by altered expression and function of PPAR isoforms after bariatric surgery. Int J Obes. 2018;42(2). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein S The case of visceral fat: argument for the defense. J Clin Invest 2004;113(11):1530–1532. doi: 10.1172/JCI200420665.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sam S, Haffner S, Davidson MH, et al. Relationship of Abdominal Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue With Lipoprotein Particle Number and Size in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:2022–2027. doi: 10.2337/db08-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Simoneau JA, Kelley DE. Subcutaneous abdominal fat and thigh muscle composition predict insulin sensitivity independently of visceral fat. Diabetes. 1997;46(10):1579–1585. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen E, Spiegelman BM. What We Talk About When We Talk About Fat. Cell. 2015;156(0):20–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012.What. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parra S, Cabré A, Marimon F, et al. Circulating FABP4 is a marker of metabolic and cardiovascular risk in SLE patients. Lupus. 2014;23(3):245–254. doi: 10.1177/0961203313517405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabré A, Lázaro I, Girona J, et al. Fatty acid binding protein 4 is increased in metabolic syndrome and with thiazolidinedione treatment in diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(1). doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishimura S, Furuhashi M, Watanabe Y, et al. Circulating levels of fatty acid-binding protein family and metabolic phenotype in the general population. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaess BM, Enserro DM, McManus DD, et al. Cardiometabolic correlates and heritability of fetuin-A, retinol-binding protein 4, and fatty-acid binding protein 4 in the framingham heart study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97(10). doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu A, Wang Y, Xu JY, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein is a plasma biomarker closely associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Clin Chem 2006;52(3):405–413. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.062463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuncman G, Erbay E, Hom X, et al. A genetic variant at the fatty acid-binding protein aP2 locus reduces the risk for hypertriglyceridemia, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(18):6970–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602178103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guaita-Esteruelas S, Bosquet A, Saavedra P, et al. Exogenous FABP4 increases breast cancer cell proliferation and activates the expression of fatty acid transport proteins. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka C V, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med 2011;17(11):1498–1503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uehara H, Takahashi T, Oha M, Ogawa H, Izumi K. Exogenous fatty acid binding protein 4 promotes human prostate cancer cell progression. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(11):2558–2568. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stejskal D, Karpisek M, Bronsky J. Serum adipocyte-fatty acid binding protein discriminates patients with permanent and temporary body weight loss. J Clin Lab Anal 2008;22(5):380–382. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotamisligil GS, Bernlohr DA. Metabolic functions of FABPs-mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(10):592–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303790.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simón I, Escoté X, Vilarrasa N, et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein as a determinant of insulin sensitivity in morbid-obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(6):1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terra X, Quintero Y, Auguet T, et al. FABP 4 is associated with inflammatory markers and metabolic syndrome in morbidly obese women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):539–547. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas AJ, Bainbridge HA, Schone JL, et al. Recruitment and Screening for a Randomized Trial Investigating Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass versus Intensive Medical Management for Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Obes Surg 2014;(24):1875–1880. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wing REA. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes melltitus: four-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;170(17):1566–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.334.Long. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Group DPPR. The Diabetes Prevention Program: Description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schweiger M, Eichmann TO, Taschler U, Zimmermann R, Zechner R, Lass A. Europe PMC Funders Group Measurement of Lipolysis. Methods Enzym. 2014;(538):171–193. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800280-3.00010-4.Measurement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;366(17):1567–1576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engl J, Ciardi C, Tatarczyk T, et al. A-FABP--a biomarker associated with the metabolic syndrome and/or an indicator of weight change? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(8):1838–1842. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu H, Hertzel A V, Steen KA, Wang Q, Suttles J, Bernlohr DA. Uncoupling Lipid Metabolism from Inflammation Through FABP-dependent Expression of UCP2. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(6):MCB.01122–14. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01122-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Djousee L GM. Plasma levels of FABP but not FABP3, are associated with increased risk of diabetes. 2012;47(8):757–762. doi: 10.1007/s11745-012-3689-7.Plasma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burak MF, Inouye KE, White A, et al. Development of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody that targets secreted fatty acid-binding protein aP2 to treat type 2 diabetes. Sci Transl Med 2015;7(319):319ra205-319ra205. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac6336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuhashi M, Hiramitsu S, Mita T, et al. Reduction of circulating FABP4 level by treatment with omega-3 fatty acid ethyl esters. Lipids Health Dis 2016;15(5):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuhashi M, Mita T, Moniwa N, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockers decrease serum concentration of fatty acid-binding protein 4 in patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res 2015;38(4):252–259. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karpisek M, Stejskal D, Kotolova H, et al. Treatment with atorvastatin reduces serum adipocyte-fatty acid binding protein value in patients with hyperlipidaemia. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(8):637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu X, Ma X, Pan X, et al. Association of androgen with gender difference in serum adipocyte fatty acid binding protein levels. Sci Rep 2016;6(1):27762. doi: 10.1038/srep27762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao H, Sekiya M, Ertunc ME, et al. Adipocyte lipid chaperone aP2 Is a secreted adipokine regulating hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ertunc ME, Sikkeland J, Fenaroli F, et al. Secretion of fatty acid binding protein aP2 from adipocytes through a nonclassical pathway in response to adipocyte lipase activity. J Lipid Res 2015;56:423–434. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M055798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furuhashi M, Hiramitsu S, Mita T, et al. Reduction of serum FABP4 level by sitagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Lipid Res 2015;56(12):2372–2380. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corripio R, Gónzalez-Clemente JM, Pérez-Sánchez J, et al. Weight loss in prepubertal obese children is associated with a decrease in adipocyte fatty-acid-binding protein without changes in lipocalin-2: A 2-year longitudinal study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163(6):887–893. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camargo A, Meneses ME, Perez-Martinez P, et al. Dietary fat differentially influences the lipids storage on the adipose tissue in metabolic syndrome patients. Eur J Nutr 2014;53(2):617–626. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.