Abstract

Objectives: Despite recent shifts in regulation and recognition of the role that naturopathy plays in health care delivery in Canada, comparatively little research has been conducted regarding individuals who conduct naturopathy-related research. A survey was undertaken to better understand the needs and capacity of these individuals to conduct more research.

Design, Setting, and Subjects: The Naturopathy Special Interest Group (N-SIG) of the Interdisciplinary Network of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (INCAM) Researchers created and distributed a survey of individuals interested in naturopathy-related research to assess gaps between current and desired research activity and needs for further participation.

Outcome measures: Results from a previous pilot study (2014; n = 58) were used to inform the design and distribution. This study received approval and oversight from the Research Ethics Board of the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine.

Results: The survey was completed by 201 individuals (∼5%–10% of all naturopathic doctors and naturopathy researchers in Canada). The majority (70%) had no peer-reviewed publication experience; however, 63% reported having published in a nonpeer-reviewed medium. Respondents reported differing levels of confidence in completing various components of a research project. Frequently selected obstacles included lack of time due to professional and personal obligations, as well as insufficient training, funding, and mentorship. The greatest identified needs for participation in research were mentorship/support, access to a wider degree of scientific journals, and targeted funding opportunities for CAM research. Overall, the results of this survey suggest that there is interest in further conducting naturopathy-related research in Canada. There are individuals who are already involved and have expressed skills in the area of evidence-based medicine. Mentorship, research training, resources, and critical appraisal and writing skills may be important leverage points.

Conclusion: Findings from this investigation will be used to inform an agenda for naturopathy-related research and activities of the N-SIG with respect to enhancing research capacity. Other CAM groups or geographic regions could consider using similar methodology to assess capacity and needs for research participation.

Keywords: naturopathy, naturopathic medicine, research, needs assessment, capacity

Introduction

Since its inception in 2004, the Interdisciplinary Network of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (INCAM) Research—now a Canadian chapter of the International Society for Complementary Medicine Research (ISCMR)—has been instrumental in defining, developing, and supporting a CAM research community in Canada. INCAM is a collaborative and interdisciplinary research network for Canadian researchers, educators, and practitioners interested in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research. One of INCAM's core values is that the body of knowledge on CAM needs to be informed by a range of perspectives, expertise, and insights.1 INCAM hosts several “Special Interest Groups” to facilitate collaboration on common research topics in areas such as massage therapy, osteopathy, and homeopathy.2 In 2014, a small group of INCAM members acknowledged a need for a more formal network to conduct research related to naturopathy in Canada and founded the INCAM Naturopathy Special Interest Group (N-SIG).

In Canada, naturopathy is regulated in six provinces, including British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Nova Scotia.3 The professional titles “Naturopath” and “Naturopathic Doctor” are restricted in these provinces. To become qualified as a naturopath, individuals must complete an undergraduate degree, be graduate from an accredited 4-year, full-time naturopathic medical program, and complete licensing and provincial board examinations. Training includes basic and diagnostic sciences as well as conventional and naturopathic approaches to treatment. The modalities used by NDs include clinical nutrition, acupuncture, botanical medicine, physical medicine, homeopathy, and lifestyle counseling.

Training at the naturopathic colleges includes a course on research methodology and evidence-based medicine (EBM).4 Some NDs pursue further research training. Studies have been undertaken to assess attitudes and perceptions of research among NDs, although to date they have been conducted in the United States rather than Canada. While attitudes were typically found to be favorable, a spectrum of attitudes ranging from “hesitancy” to “cautious embrace” is reported to exist.4

The objective of the N-SIG was to establish a national network for researchers and practitioners interested in conducting research. Having research experience or being directly involved in research were not requirements—the aim of the group was to create a community whereby members could share resources, collaborate, build research capacity, and ultimately conduct research activities in any area (clinical or nonclinical) relevant to naturopathy. With the goal to best represent the interests of the field of naturopathy research and its N-SIG members and support its members in increased participation in research, the authors acknowledged the need to first, learn about the interest level and capacity for naturopathic research in Canada, and second, develop an agenda to facilitate targeted group efforts. Capacity in this work is operationally defined to include the broad array of elements related to capacity from a systems point of view, including performance (e.g., tools, money, and equipment), person (e.g., skills and confidence), workload (e.g., staff and job tasks), supervision (e.g., reporting and monitoring systems), facilities (e.g., training centers and clinics), support service (e.g., laboratories and administrative staff), systems (e.g., communication among stakeholders and flows of information), structures (e.g., decision-making forums), and roles (e.g., authority and responsibility of individuals and teams).5 Therefore, the needs to enhance the capacity of naturopathy-related research may relate to structures, systems, and roles, staff and facilities, skills, or tools.5

Networks have been shown to be an important means for sharing information among practitioners, academicians, and researchers. While several different types of networks exist, networks generally involve groups of people who share a concern or interest and who deepen their knowledge and experience through interaction with others.6 Networks come in a variety of sizes (<10 to 100+), formats (in person and/or online), and functions. They have multiple potential purposes, including building relationships, fostering collaboration, and sharing knowledge.7–9

While the structure, design, and overall aims of a network may be predetermined in an organized manner, the interactions between the people in the network may be formal or informal. For example, knowledge sharing and exchange may involve organized discussions about a particular research study combined with informal discussion about how one can become involved in the study or how the findings of the research can be applied in practice. In an effort to develop a network that will be useful for the field of naturopathy, it was prudent to perform a more formal needs assessment survey,10 which would help identify perceived gaps from interested members in conducting more naturopathy-related research.

Overview of currently existing naturopathic research networks

Currently there are few, if any, active formalized research networks oriented specifically to the naturopathic profession. The Naturopathic Physicians Research Institute (NPRI) established the Naturopathic Physicians Research Network (NPRN)11 in 2010 with the following mandate: “To conduct research for the systematic exploration of clinical experience in naturopathic medicine in order to improve practice and the health of our patients and communities.” The Institute and Network receive no formal resources or support from academic institutions, or associations, and since its inception, activity has dwindled significantly. Very recently (June 2017), the International Research Consortium of Naturopathic Academic Clinics has been formed consisting of six founding academic institutions, represented by five teaching clinics in Australia, two in New Zealand, one in Canada, and one in the United States, and is looking to expand and affiliate alongside the World Naturopathic Federation in accordance with its international mission and lens.12 The degree to which informal research networks for naturopathic doctors exist within Canada is unknown. History suggests that there are collaborative research projects occurring in naturopathy, ultimately between individuals or groups of individuals.

Aim

To our knowledge, no other formal needs assessment has been conducted in this population to target efforts for promoting the conduct of more naturopathy-related research, a goal of the N-SIG. We conducted a survey to complete a formal assessment of needs among clinicians, researchers, educators, and administrators involved in or interested in naturopathy research in Canada. The goal was to identify potential gaps between current and desired research activity so that certain gaps could be selected and addressed. The approach included surveying clinicians, researchers, educators, and individuals about their interest in naturopathy-related research and current participation in different types of research, research training, publication, research resources, and mentorship. Additional information on demographics and desired N-SIG activities was collected.

Materials and Methods

An early version of the survey was completed in 2014 (herein referred to as “2014 survey”), receiving 58 responses primarily from Ontario NDs (90%), and more specifically, employees of the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (66%). The results of the 2014 survey were presented at the Canadian Association of Naturopathic Doctors conference, and at the INCAM Research Symposium. The limitations of small sample size, lack of respondent diversity, and lack of generalizability were acknowledged, as was the fact that this was the first attempt to collect such information from the Canadian field of naturopathy. It was decided that the survey would be refined and redistributed to reach a wider audience. Together, the 2014 survey and subsequent workshop discussion acted as important aspects of stakeholder consultation and survey development consistent with recommendations in survey research methods.13

The survey employed a questionnaire that was developed for this purpose. It was developed with input from a team of researchers with experience in survey methodology. The survey consisted of 22 questions in multiple choice and open-text field format. The survey asked about demographic information and then asked if respondents were currently participating in research or interested in participating in research. If individuals indicated that they were not participating and not interested in participating, they were asked about obstacles to participation and their beliefs about the role of research in CAM only. The questions related to belief regarding the value of EBM were obtained from a survey of Traditional Chinese Medicine school faculty members.14 The remaining questions, constituting the full survey, related to needs, resources, publication, and training history, were only completed by individuals who indicated that they were currently participating in, or interested in participating in, research related to naturopathy.

The survey was created on Surveymonkey.com and circulated through the INCAM Newsflash (the monthly e-mail correspondence to all INCAM members), naturopathic provincial association correspondence in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, and through educational institutions (Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine and Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine). The remaining provincial associations were contacted, but did not participate in dissemination of the survey. The Ontario Association of Naturopathic Doctors distributed postcards advertising the survey at their annual conference. In addition, it was shared through the Facebook and Twitter accounts for CCNM Research and in a large closed naturopathy practitioner Facebook group. Distribution took place from October 2017 to January 2018. The efforts to engage responses were primarily web-based due to resource limitations.

Participants were informed that their data would be stored confidentially and only reported anonymously in aggregate form. The study received approval and oversight from the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine Research Ethics Board.

Results

Response

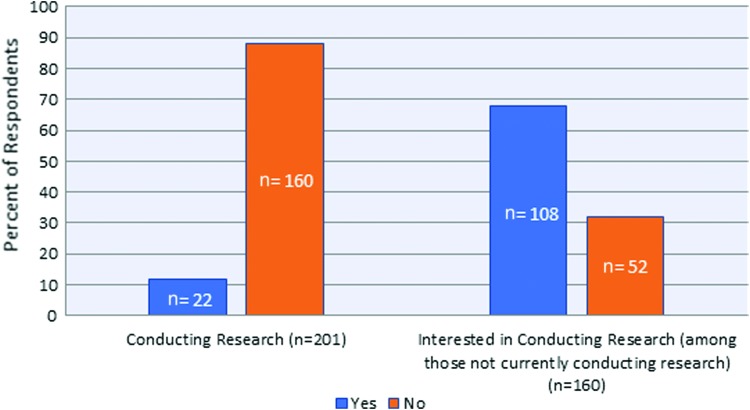

The survey was completed by 201 individuals, of which, 7 reported current membership in the N-SIG. Fifty-two individuals indicated that they were not currently involved and not interested in becoming involved in research and completed the shortened version of the survey. The completion rate was 68% with an average completion time of 10 min. This average incorporates those who completed both the complete and shortened versions. Table 1 presents demographic information about the survey respondents. Figure 1 displays the number of respondents currently conducting naturopathy-related research or interested in conducting research, and Figure 2 displays the specific type of research methodology. The majority of respondents (88%) reported not currently conducting research. Of those conducting research, 60% reported 5+ years of research experience, while a smaller proportion (20% each) had 2–4 years, or shorter than 1 year of research experience.

Table 1.

Demographic Information

| INCAM Member (%) | |

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 76 |

| Unsure | 17 |

| Role (%) | |

| Naturopathic doctor | 97 |

| Educator | 22 |

| Researcher/research staff | 10 |

| Administrator | 2 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 77 |

| Male | 21 |

| Age (%) | |

| 20–29 | 15 |

| 30–39 | 51 |

| 40–49 | 22 |

| 50–59 | 8 |

| 60+ | 6 |

| Province (%) | |

| Ontario | 61 |

| British Columbia | 11 |

| Alberta | 10 |

| Nova Scotia | 5 |

| Manitoba | 5 |

| New Brunswick | 4 |

| Quebec | 2 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 |

| North West Territories | 1 |

| Heard about survey (%) | |

| CCNM email | 54 |

| Private/closed Facebook group | 21 |

| Social media post | 14 |

| CAND e-mail | 9 |

| IN-CAM newsflash e-mail | 4 |

| BINM e-mail | 3 |

| ISCMR newsletter | 1 |

| Research-related training (includes those in progress) (%) | |

| Professional designation | 98 |

| Bachelor's degree | 90 |

| Continuing professional education | 70 |

| Master's degree | 12 |

| Doctor of philosophy | 2 |

| Clinical research coordinator/associate certification (SoCRA CCRP/CRA, etc.) | 3 |

| On-the-job training | 2 |

| Other (including Cochrane training, Residency program, and other programs) | 2 |

INCAM, Interdisciplinary Network of Complementary and Alternative Medicine; ISCMR, International Society for Complementary Medicine Research.

FIG. 1.

Current research participation and interest in participation. Color images are available online.

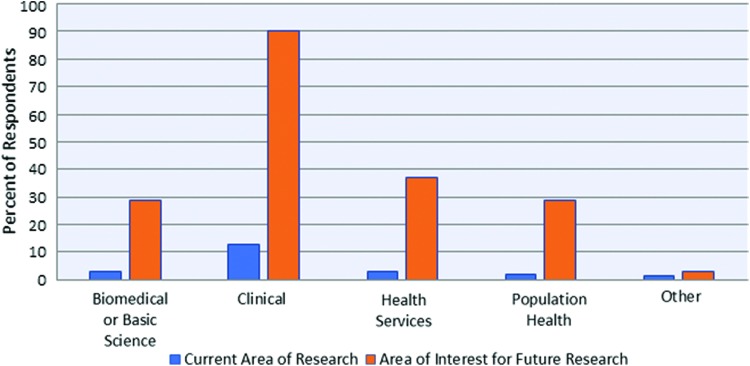

FIG. 2.

Areas of current research and areas of interest for future research among those currently participating in research or interested in participating in research (n = 130). Color images are available online.

Participants were queried about their publication history. Table 2 presents the number of respondents who had completed different types of publications as well as the median number of publications within each type. In addition, we asked about nonpeer-reviewed publications and 63% reported some form of published work with a high number of articles for the general public (47%) and professional journals or magazines (34%).

Table 2.

Peer-Reviewed Publication History

| Type of peer-reviewed publication | Percent of respondents who have published (n = 97) | Median number of publications (25th and 75th percentile) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 70 | |

| Basic science research | 8 | 1.5 (1, 2.5) |

| Practice guidelines | 4 | 1 (1, 1.5) |

| Systematic review or meta-analysis | 8 | 2 (1, 4.75) |

| Randomized controlled trial or observational study | 8 | 1 (1, 1.25) |

| Case report | 8 | 1 (1, 2) |

| Review article | 18 | 2 (1, 3) |

Of those interested in research, 79% were interested in pursuing additional research training. Continuing professional education and self-taught study was ranked highest for the types of training (84% and 76% respectively), with 28% interested in a master's degree, 18% in a clinical research coordinator or associate certificate, and 9% in a doctor of philosophy degree.

Research literacy, skills, and the importance of evidence

With respect to motivation to participate in research, “advancement of clinical efficacy knowledge” and “advancement of public and interprofessional perception of naturopathy” rated highest at 92% and 82%, respectively.

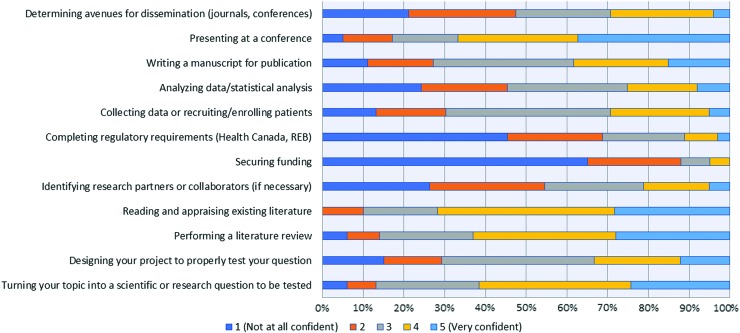

Participants were queried about confidence in their abilities to complete various stages of the research process. The responses are displayed in Figure 3. Confidence was highest in presenting research, performing a literature search, and appraising existing literature; and lowest in securing funding and completing regulatory requirements.

FIG. 3.

Confidence in abilities to perform various components of research. Color images are available online.

When asked about their beliefs related to the value of EBM, the responses indicated a very high value of evidence. Between 84% and 100% of participants agreed to all statements indicating agreement of the importance of critical evaluation of methodology and outcomes, to the importance of defining and assessing successful outcomes, and that using evidence from clinical trials improves clinical care. When comparing the responses of those interested in participating in naturopathy research and those not interested, the results were highly similar.

We also employed questions from the same previously conducted survey related to confidence in different research skills.14 Both, those interested and those not interested in conducting research, reported high confidence in searching the web for relevant literature. Those interested were more confident in critically appraising literature and reported reading journal articles on a weekly basis (both 75%) compared to those not interested (both 57%).

Resources and limitations to participation

Common limitations for involvement in research included perceived lack of time due to professional or personal obligations, as well as concerns related to lack of education/training/skills, lack of confidence, interest, funding, resources, and mentorship. Those that indicated that they were not interested in naturopathy-related research also indicated a lack of time and highly ranked lack of funding, support/mentorship, and resources.

With respect to resources available to facilitate research activities, overall participants rated online and print resources, databases, clinical notes and records, and office or laboratory space as being adequate, and subscriptions, applications, software, research personnel, expertise, and equipment as being inadequate.

Participants were given the opportunity to list their needs for research through open text. The majority of responses related to funding, mentorship and support, training and education, and time, with smaller proportions reporting a lack of collaborative opportunities, access to journal articles, confidence, and interest. A small number reported concerns such as access to a research ethics board, affiliation and credential status, leadership, uncertainty about the ability to achieve a meaningful outcome, and trustworthiness of funding sources and information obtained.

When asked about the resources that participants would be interested in to facilitate involvement in research activities, all possible options were selected to a high degree (between 68% and 82%). These included education and training, availability of funding, collaborative opportunities, access to tools, and mentorship.

N-SIG activities

Participants reported their interest in activities and avenues for the N-SIG to support its members in research activities. The activities that were rated highest in importance included supporting educational or training opportunities, participating in the biannual INCAM research symposium, and maintaining the INCAM webpages highlighting SIG activities.

In terms of the cost of membership in N-SIG, respondents were most likely to indicate a willingness to pay an annual membership of $0–50 or $50–100 Canadian Dollars, although many also selected the option of paying individually for activities to reduce fees.

When asked about the preferred format of learning opportunities, self-guided study, teleconferences/webinar, and small group sessions were rated highest.

Mentorship

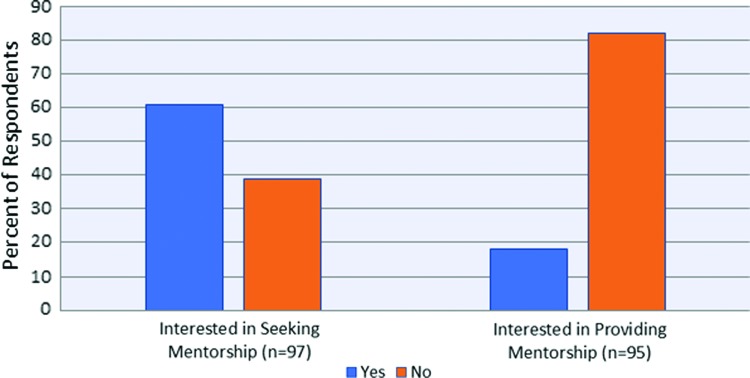

A high level of interest was expressed with respect to seeking mentorship (61% of those interested in research). A smaller percentage (18%) was interested in providing mentorship (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Percentage of participants interested in seeking and providing mentorship. Color images are available online.

Discussion

Overall, the results of this survey suggest that there is interest for participation in naturopathy-related research, and that gaps exist between the current and desired levels of involvement. There are individuals who are already involved, have completed training, and have published research. There are also a significant number of individuals who are not currently, but are interested in, getting involved in research. There is interest in receiving additional training and support as well as mentorship. There are also many identified obstacles and needs that have been highlighted in this survey, which can serve as opportunities for the N-SIG to facilitate further participation.15 Resources allocated to supporting access to scientific literature, as well as critical appraisal and writing skills, may be important leverage points for supporting the needs of this field of research, as well as access to funding opportunities and support in accessing existing funding.

There is significant importance placed on evidence as well as confidence and skill in tenants of EBM, consistent with other professions surveyed using similar questions.14,16 It is possible that attitudes and perceptions about EBM may be involved in the low survey response rate. While there was a very high level of agreement about the importance of CAM research between those who were interested in participating in naturopathy-related research and those who were not, it is not possible to compare the views of those who declined participation in the survey. While some NDs value and warmly welcome scientific inquiry, it is known that some express concerns about a limited definition of EBM, possibly related to its use in dismissing naturopathic therapies as being ineffective or its use in the opposition of recognition, licensing, scope of practice, and insurance reimbursement. There is concern that the use of EBM may take away from the profession's philosophy-driven approach, that the current methodologies used to study individual therapeutic agents may be not appropriate for the study of complex, multimodal therapeutic approaches used by NDs, and that other forms of evidence may be discounted4,17 as a result of greater focus on EBM. The impact of culture change on the participation rate and results of this study is unclear and a limitation.

Mentorship has been cited as a success strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research, and practice, resulting in improvements in knowledge, skills, and behavior.18 Factors that foster successful implementation of mentorship programs include leadership, infrastructure, and culture change incentives.19 Development of research mentorship programs within the N-SIG and INCAM could provide a template for larger-scale mentorship implementation in educational institutions and professional associations.

This survey was more successful than the initial iteration (the 2014 survey) at capturing participants from across Canada, although there was still a strong response from Ontario. Some limitations of this survey include a relatively low response rate. There are ∼2000 naturopathic doctors in Canada, thus the sample of 201 makes up about 10%. However, this is based on the assumption that all NDs in Canada received the invitation to participate, which is highly unlikely. As a result, the response rate is likely to be a significant underestimate. Calculation of the margin of error yields a result of 6.9%, which is acceptable. Because the results of interest are primarily qualitative and this is the first attempt to collect such information, the results are relevant.

Distribution of the study was limited by a lack of funding and relied on free web-based methods. As with any survey, response rate depends greatly on participation of members and buy-in from key stakeholders. Improved stakeholder engagement would be paramount to the success for future surveys. In addition, our distribution strategies were targeted at those most likely to be interested in naturopathy-related research, primarily naturopathic doctors and educators. Individuals from other professions, such as medical doctors and chiropractors, while not practitioners of naturopathy, may use or study modalities that overlap with naturopathy such as nutrition and dietary counseling, botanical medicine, and physical medicine. Those interested in a similar field of study may not have been aware of the opportunity to participate. Their differing training, institutional affiliation, and resource availability may have resulted in different responses that were not captured. In addition, there may be a bias in the respondents with those interested in research more likely to participate in the survey. As a result, generalizability of the findings within both the Canadian and global context may be limited. However, the similarities in responses between those interested in research and those who are not, suggest that these findings might be representative on a larger national scale.

With respect to future research, further refinement on how to enhance capacity at various levels could be undertaken. This may involve conducting more in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and leaders in the area of naturopathy-related research, as well as further identification of barriers and facilitators to participation. These may be a useful way to explore attitudes and perspectives related to evidence and research, provide insight for further study design to capture attitudes and perspectives, and provide valuable information about how to implement cultural change.

Other groups of CAM practitioners could use a similar process to investigate the needs of individuals to facilitate participation in research as well as learn from some of the obstacles encountered in the conduct of this survey.

Conclusions

The results of this survey demonstrate a clear set of needs and provide significant guidance on how the N-SIG can support individuals interested in participating in naturopathy-related research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Jacka Foundation of Natural Therapies, Blackmores Institute, and Blackmore Foundation for their generous support of Kieran Cooley as a competitively appointed Fellows on the UTS:ARCCIM International Naturopathy Research Leadership Program, to the Canadian INCAM Researchers for their support of the N-SIG, and to each of the provincial Naturopathic associations who helped to disseminate the survey. The work presented here is the sole responsibility of the named authors and the partners listed above have had no influence upon any aspect of the research outlined in this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. About INCAM, ISCMR Website. Online document at: www.iscmr.org/content/incam/about-incam, accessed August8, 2018

- 2. International Society for Complementary Medicine Research (ICSMR). ISCMR's Special Interest Groups (SIGs). 2016. Online document at: www.iscmr.org/content/public-iscmrs-special-interest-groups, accessed April3, 2017

- 3. About Naturopathic Medicine, CAND Website. Online document at: www.cand.ca/naturopathic-medicine-today, accessed August8, 2018

- 4. Goldenberg JZ, Burlingham BS, Guiltinan J, Oberg EB. Shifting attitudes towards research and evidence-based medicine within the naturopathic medical community: The power of people, money and acceptance. Adv Integr Med 2017;4:49–55 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: A hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wenger E, McDermott R, Snyder W. Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palmer D, Kramlich D. An introduction to the multisystem model of knowledge integration and translation. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2011;34:29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kislov R, Harvey G, Walshe K. Collaborations for leadership in applied health research and care: Lessons from the theory of communities of practice. Implement Sci 2011;6:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bate P, Robert G. Knowledge management and communities of practice in the private sector: Lessons for modernizing the National Health Service in England and Wales. Public Adm 2002. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9299.00322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaufman R, English F. Needs Assessment: Concept and Application. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications, Inc., 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steel A, Sibbritt D, Schloss J, et al. . An overview of the Practitioner Research and Collaboration Initiative (PRACI): A practice-based research network for complementary medicine. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steel A, Goldenberg J, Cooley K. Establishing an international research collaborative for naturopathy: The International Research Consortium of Naturopathic Academic Clinics (IRCNAC). Adv Integr Med 2017;4:93–97 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA, Nyandieka L, Wanjau J. Methods for pre-testing and piloting survey questions: Illustrations from the KENQOL survey of health-related quality of life. Health Policy Plan 2002;17:322–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson BJ, Kligler B, Taylor B, Cohen HW, et al. . Faculty survey to assess research literacy and evidence-informed practice interest and support at Pacific College of Oriental Medicine. J Altern Complement Med 2014;20:705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veziari Y, Leach MJ, Kumar S. Barriers to the conduct and application of research in complementary and alternative medicine: A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allen ES, Connelly EN, Morris CD, Elmer PJ, et al. . A train the trainer model for integrating evidence-based medicine into a complementary and alternative medicine training program. Explore 2011;7:88–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jane Guiltinan ND, Goldenberg JZ, McCarty RL. The role of evidence-based medicine in naturopathy. Adv Integr Med 2017;4:47–48 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Perrier L, Bell M, et al. . Exploring mentorship as a strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research and practice: A scoping systematic review. Implement Sci 2014;9:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gagliardi AR, Webster F, Straus SE. Designing a knowledge translation mentorship program to support the implementation of evidence-based innovations. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]