Abstract

Quercetin and its metabolite isorhamnetin elicit various beneficial effects on human health. However, their bioavailability is low. In this study, we investigated whether low concentrations in the physiological range could promote glucose uptake in L6 myotubes, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms. We found that 0.1 nM and 1 nM quercetin or 1 nM isorhamnetin significantly increased glucose uptake via translocation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane of L6 myotubes. Quercetin principally activated the CaMKKβ/AMPK signalling pathway at these concentrations, but also activated IRS1/PI3K/Akt signalling at 10 nM. In contrast, 1 nM and 10 nM isorhamnetin principally activated the JAK/STAT pathway. Treatment with siAMPKα and siJAK2 abolished quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation, respectively. However, treatment with siJAK3 did not affect isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation, indicating that isorhamnetin induced GLUT4 translocation mainly through JAK2, but not JAK3, signalling. Thus, quercetin preferably activated the AMPK pathway and, accordingly, stimulated IRS1/PI3K/Akt signalling, while isorhamnetin activated the JAK2/STAT pathway. Furthermore, after oral administration of quercetin glycoside at 10 and 100 mg/kg body weight significantly induced GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane of skeletal muscles in mice. In the same animals, plasma concentrations of quercetin aglycone form were 4.95 and 6.80 nM, respectively. In conclusion, at low-concentration ranges, quercetin and isorhamnetin promote glucose uptake by increasing GLUT4 translocation via different signalling pathways in skeletal muscle cells; thus, these compounds may possess beneficial functions for maintaining glucose homeostasis by preventing hyperglycaemia at physiological concentrations.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), an epidemic metabolic disorder, is characterized by hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia resulting from not only impaired insulin secretion, but also insulin resistance. The prevalence of diabetes is growing considerably: the current number of diabetic patients (285 million) is expected to double by 20351. The disease tends to affect younger individuals as a result of diet, behaviour, and obesity2. Chronic diabetes is usually accompanied by serious diabetic complications, such as cardiac dysfunction and paropsia disease3,4. Therefore, distinguishing novel way to improve insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity is a priority target for treatment or prevention of DM.

Skeletal muscle exerts profound effects on whole-body glucose homeostasis, especially with regard to regulation of hyperglycaemia in the postprandial state. Glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4), which is specifically expressed in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue5,6, is a determinant of glucose transporter for these tissues. Upon insulin stimulus, GLUT4 rapidly translocates to the cell surface from intracellular storage vesicles, which is involved in the activating various protein kinases, including insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and Akt7,8. Notably, exercise and energy depletion activate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its upstream kinases, such as Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase (CaMKK) and liver kinase B1 (LKB1), to promote GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake9,10. In the last two decades, Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) have attracted considerable interest in the context of energy metabolism11. Activated JAK2 and JAK3 alter intracellular signalling to result in the activation of signal transducers and transcriptional activators, such as STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5, that participate in multiple biological responses, including tissue homoeostasis, apoptosis, and oncogenesis12,13. In addition, activation of the JAK3/STAT3 signalling pathway is involved in glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells11.

Numerous studies have asserted that flavonoids promote translocation of GLUT4 by different signalling pathways in various tissues and cells. For example, flavonoids from propolis extract improve glucose uptake by promoting GLUT4 translocation through both PI3K- and AMPK-dependent pathways in skeletal muscle14; whereas, epigallocatechin gallate induces GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle through insulin signalling pathways15, and procyanidin promotes translocation of GLUT4 in muscle of mice through activation of insulin and AMPK signalling pathways16. Quercetin (3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxy flavone) and isorhamnetin (3′-O-methyl quercetin) are considered potential therapeutic agents for various diseases, such as obesity and cancer, as they modulate metabolism, regulate DNA transcription, and activate apoptosis17–20. In a previous study, quercetin at 50 mg/kg body weight ameliorated oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic male rats21. However, it is important to note that quercetin is poorly absorbed from the intestine. Hence, extensive knowledge of physiological concentrations of quercetin and isorhamnetin are essential for establishing their effects. The absorption rate of quercetin is reportedly 9–20% in humans22–24, and basal concentrations of quercetin in the blood range from 300 to 750 nM after consumption of 80–100 mg of quercetin equivalent in humans24–26. Furthermore, physiological concentrations of quercetin in tissues are much more important than their plasma concentrations. In rats and mice, physiological concentrations of quercetin in muscle ranged from 0.1 nM to 163 nM24,25. In Caco-2 cells, absorption of quercetin was reported to be at the nM level27. It is, therefore, necessary to clarify the functions of quercetin and its metabolite isorhamnetin and their underlying mechanism within a physiological concentration range.

In the present study, we investigated whether the mechanism underlying the antidiabetic properties of quercetin and isorhamnetin at a physiological concentration range (nM level) involved promotion of glucose uptake in differentiated L6 myotube cells. We found that 0.1 nM and 1 nM quercetin or 1 nM isorhamnetin significantly enhanced glucose uptake and was accompanied by increased GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane of L6 cells by different signalling pathways. Furthermore, we confirmed that after oral administration of quercetin glycoside significant induced GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane of skeletal muscles in ICR mice.

Results

Quercetin and isorhamnetin promoted glucose uptake in L6 myotubes

We first investigated whether quercetin or isorhamnetin (chemical structures are shown in Fig. 1) could promote glucose uptake at 0.01–104 nM in L6 myotubes. The results showed that quercetin and isorhamnetin increased glucose uptake in a dose-dependent manner from 0.01 nM to 1 nM (Fig. 2), compared with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) treatment. A significant increase was observed at 0.1 nM and 1 nM quercetin, and 1 nM isorhamnetin. At 10 nM, both compounds decreased glucose uptake. However, they again increased glucose uptake at a higher concentration range in a dose-dependent manner. At 1 μM and 10 μM, both compounds elicited a significant increase. From these results, quercetin and isorhamnetin facilitated a biphasic increase in glucose uptake in L6 myotubes.

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of quercetin and isorhamnetin.

Figure 2.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin (A) and isorhamnetin (B) at the indicated concentrations for 4 h. Glucose uptake was determined using an enzymatic 2DG uptake assay. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). * and ** indicate significant differences from control cells by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively).

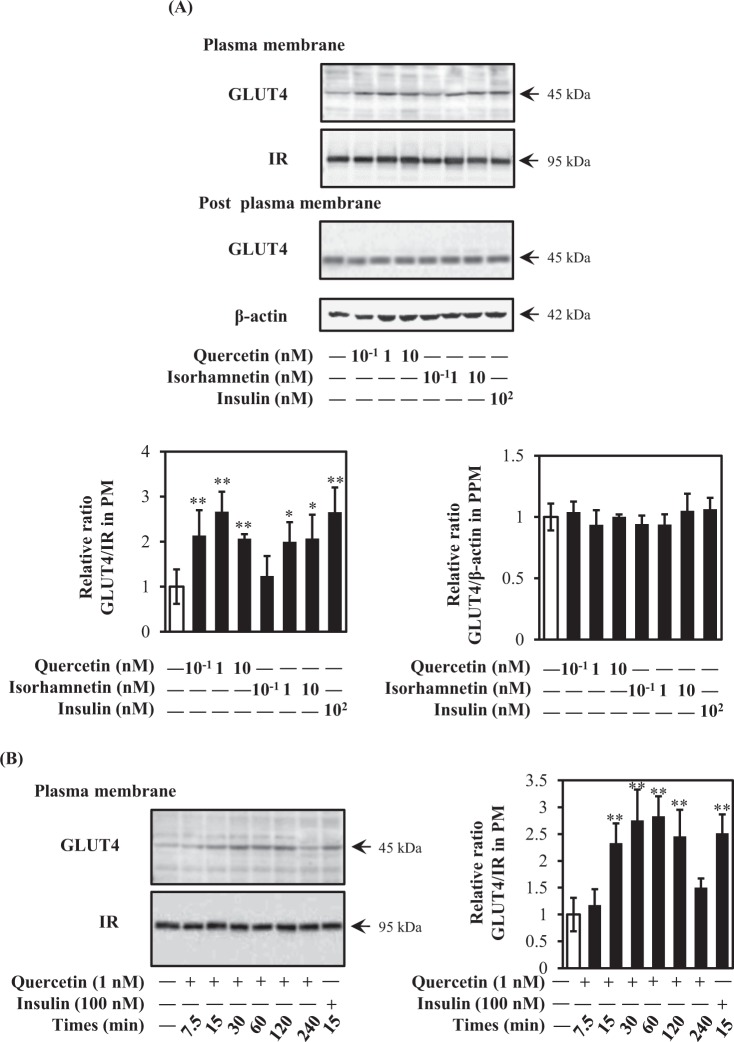

Quercetin and isorhamnetin promote GLUT4 translocation

Because GLUT4 incorporates glucose into skeletal muscle cells after translocation from intracellular storage sites to the plasma membrane, we next investigated GLUT4 translocation after treatment of L6 myotubes with quercetin or isorhamnetin at 0.1–10 nM for 15 min. With the exception of 0.1 nM isorhamnetin, both compounds significantly increased GLUT4 translocation to almost the same extent as the 100-nM insulin positive control (Fig. 3A). However, the expression level of GLUT4 remained unchanged (Fig. 3A). When time-dependent changes in GLUT4 translocation were monitored for 240 min, quercetin-induced translocation exhibited a bell-shaped curve: a significant increase appeared at 15 min and then the translocation level plateaued from 30 to 60 min, decreased from 60 min, and was restored by 240 min (Fig. 3B). From these results, quercetin and isorhamnetin at a physiological concentration range increased glucose uptake by promoting GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane without altering GLUT4 expression levels in L6 myotubes.

Figure 3.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on GLUT4 translocation in L6 myotubes. (A) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. Plasma membrane fractions were prepared and subjected to analysis of GLUT4 translocation by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of GLUT4 to IRβ. (B) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with 1 nM quercetin for the indicated times (0–240 min). Plasma membrane fractions were prepared and subjected to analysis of GLUT4 translocation by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of GLUT4 to IRβ. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). * and ** indicate significant differences from control cells by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively).

Quercetin activated both insulin- and AMPK-dependent pathways in L6 myotubes

Translocation of GLUT4 is mainly regulated by insulin- and AMPK-dependent pathways. To explore molecular mechanisms of quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation, involvement of these pathways was examined. Both quercetin and isorhamnetin failed to activate phosphorylation of insulin receptors (IRs) at all concentrations tested (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, quercetin, but not isorhamnetin, dose-dependently promoted phosphorylation of IRS1, a downstream target of IR. In addition, quercetin significantly increased phosphorylation of PI3K, which is downstream of IRS1 (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, 0.1 nM isorhamnetin also increased PI3K phosphorylation without affecting IRS1 phosphorylation. Regarding Akt, 10 nM quercetin increased Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 as the same extent as insulin, while isorhamnetin did not affect Akt phosphorylation. However, quercetin and isorhamnetin did not affect expression level of these proteins. At higher concentrations, quercetin and isorhamnetin significantly increased Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 4.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on the insulin signalling pathway in L6 myotubes. Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to analysis of phosphorylation and expression of proteins in the insulin signalling pathway by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. (A) Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-IR to IR or p-IRS1 to IRS1. (B) Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-PI3K to PI3K or p-Akt to Akt. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). * and ** indicate significant differences from control cells by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively).

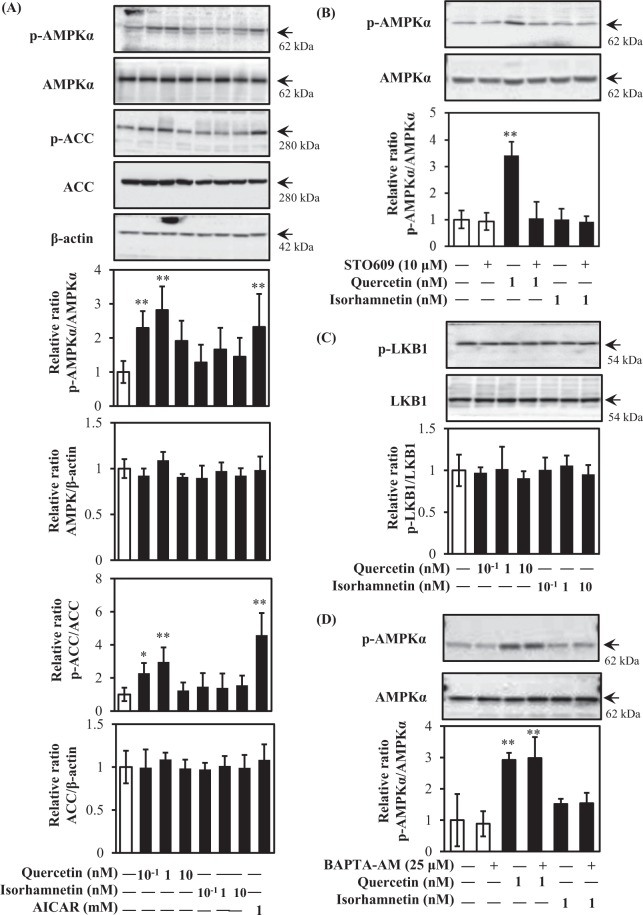

AMPK is recognized as a metabolic sensor for the prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes6,9. GLUT4 translocation is triggered by the activation of AMPK as an insulin-independent mechanism10. As shown in Fig. 5, 0.1 nM and 1 nM quercetin, but not isorhamnetin, promoted AMPK phosphorylation similar to the positive control 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxyamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) (Fig. 5A). At higher concentrations (1 μM and 10 μM), both compounds induced phosphorylation of AMPK (Supplementary Fig. 2). Phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), a downstream target of AMPK, also showed the same trend as phosphorylation of AMPK, i.e., phosphorylation was increased by treatment with 0.1 nM or 1 nM quercetin. To obtain further information about factors upstream of AMPK, we examined the involvement of LKB1, CaMKKβ, and intracellular-free calcium (Ca2+). As shown in Fig. 5B, the CaMKKβ inhibitor STO-609 abolished quercetin-induced AMPK phosphorylation. In contrast, neither quercetin nor isorhamnetin increased LKB1 phosphorylation (Fig. 5C). The intracellular Ca2+ chelator 1,2-Bis (2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetrakis (acetoxymethyl ester) (BAPTA-AM) did not affect quercetin-induced AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 5D). These results indicated that quercetin principally activated the CaMKKβ/AMPK signalling pathway at 0.1 and 1 nM, and activated the IRS1/PI3K/Akt signalling pathway at 10 nM to induce GLUT4 translocation in L6 cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on the AMPK signalling pathway in L6 myotubes. Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min in the absence or presence of STO-609 or BADPA-AM, respectively. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to analysis of phosphorylation and expression of proteins in the AMPK signalling pathway by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. (A) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-AMPK to AMPK, or p-ACC to ACC. (B) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min in the presence of STO-609. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-AMPK to AMPK. (C) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-LKB1 to LKB1. (D) Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min in the presence of BADPA-AM. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of p-AMPK to AMPK. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). * and ** indicate significant differences from control cells by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively).

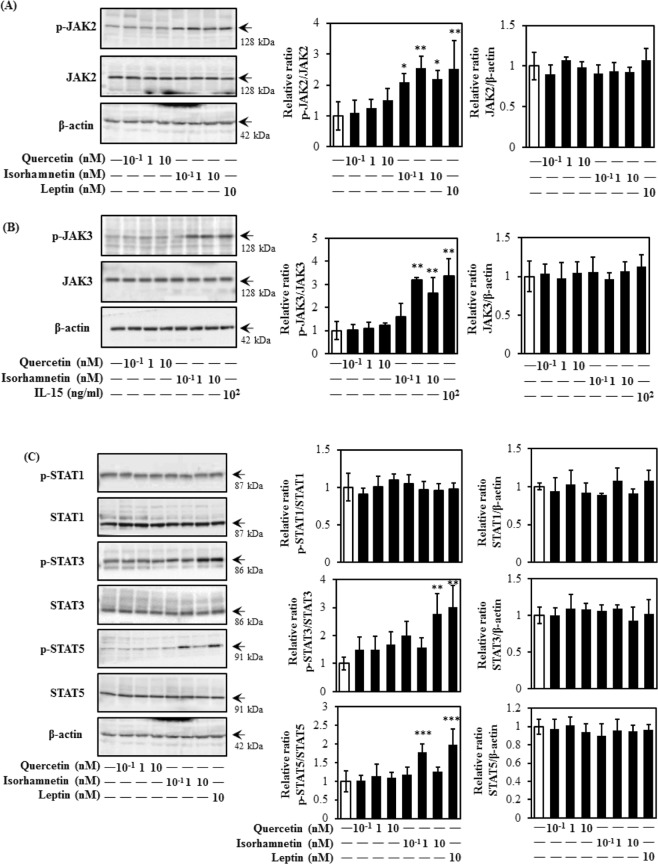

Isorhamnetin activated a JAK/STAT-dependent pathway in L6 myotubes

The JAK/STAT-pathway is associated with maintaining glucose homeostasis and inducing translocation of GLUT411. As shown in Fig. 6, isorhamnetin, but not quercetin, effectively promoted JAK2 and JAK3 phosphorylation at a physiological concentration range (Fig. 6A,B). Concurrently, phosphorylation of downstream targets STAT3 and STAT5, but not STAT1, were increased by isorhamnetin at 10 nM and 1 nM, respectively (Fig. 6C). As shown in Supplemental Fig. 3, both isorhamnetin and quercetin induced phosphorylation of JAK2 at higher concentrations (1 μM and 10 μM). From these results, isorhamnetin at physiological concentrations induced translocation of GLUT4 through the JAK/STAT pathway.

Figure 6.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on the JAK/STAT signalling pathway in L6 myotubes. Differentiated L6 myotubes were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to analysis of phosphorylation and expression of proteins in the JAK/STAT signalling pathway by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of (A) p-JAK2 to JAK2, (B) p-JAK3 to JAK3, or (C) p-STAT1 to STAT1, p-STAT3 to STAT3, or p-STAT5 to STAT5. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). *, **, and *** indicate significant differences from control cells by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001, respectively).

To further confirm the roles of AMPKα, JAK2, and JAK3 in quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation, siRNA was introduced. As shown in Fig. 7A, siRNA for AMPK almost completely abolished quercetin- and AICAR-induced GLUT4 translocation to the control level, but failed to suppress isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation. In contrast, siRNA for JAK2 abolished isorhamnetin- and leptin-induced GLUT4 translocation without affecting quercetin-induced GLUT4 translocation (Fig. 7B). Isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation was slightly decreased after treatment with siRNA for JAK3, although this was not significant (Fig. 7C). From these results, we confirmed that quercetin-induced GLUT4 translocation to the cell surface is primarily dependent on the AMPK pathway, while isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation is mainly due to JAK2, but not JAK3, signalling. These results indicated that AMPKα and JAK2 contributed to the GLUT4-mediated glucose uptake induced in muscle cells by quercetin and isorhamnetin, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect of quercetin and isorhamnetin on GLUT4 translocation via AMPK- and JAK/STAT-dependent pathways. Differentiated L6 myotubes were transfected with siRNAs targeting (A) AMPKα, (B) JAK2, (C) JAK3, or control siRNA and treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. The plasma membrane fraction was prepared and subjected to analysis of GLUT4 translocation by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Representative data are shown from independent triplicate analyses. Band density was measured and represented as the ratio of GLUT4 to IRβ. Data shown represent mean ± SD (n = 3). * and ** indicate significant differences from control cells by student’s t-test (*p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 respectively). Values with the same letters are not significantly different by Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test (p < 0.05).

Enzymatically modified isoquercitrin (EMIQ) promote GLUT4 translocation in vivo

Quercetin mainly exists in plant and plant-derived foods as its glycoside forms, such as rutin (quercetin-3-O-β-rutinoside) and isoquercitrin (quercetin-3-O-β-glucoside)28. Enzymatically modified isoquercitrin (EMIQ, chemical structure is shown in Fig. 8A) is a quercetin derivatives having 1–8 linear glucose moiety at C-3 position of quercetin structure29. It was reported that the bioavailability of EMIQ is 17-fold higher than that of quercetin29. Thus, EMIQ was orally given to ICR mice at 10, 100 and 1000 mg/kg body weight, and GLUT4 translocation in muscle of mice was determined. As a result, EMIQ at 10 and 100 mg/kg body weight significantly induced GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane in skeletal muscles of mice (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Effect of EMIQ on GLUT4 translocation in mice. (A) The chemical structures of EMIQ. (B) GLUT4 translocation in mice muscle 90 min after oral administration of EMIQ. Plasma membrane fraction was prepared and subjected to analysis of GLUT4 translocation by western blotting. Arrow showed the target protein bands. Original blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Each bar graph shows typical result from five animals. The band density was measured and represented as the ratio of GLUT4/IRβ in the plasma membrane fraction or the ratio of GLUT4/β-actin in tissue lysate. Data were shown as the mean ± SE (n = 5). * and ** indicate significant difference from the control group by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01).

Furthermore, we quantified the plasma concentration of quercetin and isorhamnetin after administration of EMIQ by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). As shown in Table 1, the concentrations of quercetin aglycone in the plasma were 4.95 ± 0.82 nM, 6.80 ± 2.00 nM, and 138.43 ± 45.14 nM, 90 min after oral administration of EMIQ at 10, 100, and 1000 mg/kg body weight, respectively. Meantime, the total (aglycone plus conjugated forms) concentrations of quercetin were 11.69 ± 3.99 nM, 54.89 ± 27.44 nM, and 571.60 ± 225.41 nM. After administration of EMIQ at 1000 mg/kg body weight, isorhamnetin aglycone was detected at 130.74 ± 51.52 nM, though it was not detected in the plasma after administration of EMIQ at 10, and 100 mg/kg body weight. The total concentrations of isorhamnetin were 2.75 ± 2.77 nM, 14.62 ± 4.62 nM, and 351.83 ± 139.88 nM, after administration of EMIQ at 10, 100, and 1000 mg/kg body weight. These results suggested that quercetin at a physiological concentration range induced GLUT4 translocation in vivo.

Table 1.

Concentrations of quercetin and isorhamnetin in plasma of mice after orally administration of EMIQ.

| Compounds | EMIQ 10 mg/kg body weight | EMIQ 100 mg/kg body weight | EMIQ 1000 mg/kg body weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Aglycone form | 4.95 ± 0.82 | 6.80 ± 2.00 | 138.43 ± 45.14 |

| Conjugated form | 11.69 ± 3.99 | 54.89 ± 27.44 | 571.60 ± 225.41 | |

| Isorhamnetin | Aglycone form | N.D. | N.D. | 130.74 ± 51.52 |

| Conjugated form | 2.75 ± 2.77 | 14.62 ± 4.62 | 351.83 ± 139.88 | |

ICR mice were orally administrated EMIQ at 10, 100, or 1000 mg/kg body weight, or water as a vehicle control after 18 h fasting. Blood was collected from a cardiac puncture 90 min after the administration. Plasma was prepared and used for measurement of quercetin and isorhamnetin by HPLC with or without deconjugation.

Discussion

Prevention of hyperglycaemia is important to reduce the onset of diabetes mellitus. As a result of the drug resistance and toxic side effects associated with current chemotherapy, scientists have recently paid greater attention to food components, especially polyphenols and polyphenol-rich food materials. For example, procyanidin-rich cacao liquor procyanidin extract5, glabridin6, and epigallocatechin gallate15 have been reported to prevent hyperglycaemia. Quercetin is one of the most abundant dietary flavonoids and its average daily consumption is 25–50 mg per day30. Quercetin metabolism mainly occurs in the small intestine and liver, where quercetin is biotransformed to isorhamnetin and tamarixetin31,32. Quercetin and isorhamnetin have positive impacts on many health functions, including reduced risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and obesity18–21. Nonetheless, their poor bioavailability22–24,33 limits their clinical applications. Considering these concerns, it is imperative to clarify if their beneficial functions occur within a physiological concentration range which can be achieved by dietary intake. In this study, we first observed that physiological concentrations of both quercetin and isorhamnetin promoted glucose uptake and induced GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane in rat L6 skeletal muscle cells.

Quercetin and isorhamnetin elicited a biphasic increase in glucose uptake in L6 myotubes. They increased glucose uptake in a dose-dependent manner from 0.01 nM to 1 nM and decreased glucose uptake at 10 nM and 100 nM (Fig. 2). However, they again increased glucose uptake at 1 μM and 10 μM in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). This intriguing complicated biphasic increase in glucose uptake is speculated to involve migration and various non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic interactions in the solvent34. These interactions are involved in complexation of quercetin and isorhamnetin with macromolecules, which affects the solubility and absorption rate of quercetin and isorhamnetin in target tissues35. Another possible explanation is that serotonylation of Rab and/or Rho proteins are involved in the underlying mechanism of quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced glucose uptake. Serotonin reportedly shows a similar biphasic increase trend of glucose uptake by serotonylation of the small GTPase Rab4 in L6 cells36. These results may explain, at least in part, the biphasic action of quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced glucose uptake observed in this study, although further experiments are needed to clarify this unique action.

Although isorhamnetin is a metabolite of quercetin, they have different physiological properties in terms of radical scavenging, enzymatic, and vasodilator activities32. In this study, physiological concentrations of quercetin and isorhamnetin promoted GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane in L6 myotubes through different mechanisms without altering GLUT4 expression. Quercetin principally activated CaMKKβ/AMPK/ACC signalling at 0.1 nM and 1 nM (Fig. 5). Quercetin- and AICAR-induced glucose uptake (data not shown) and GLUT4 translocation were significantly suppressed by siRNA for AMPK. CaMKKβ belongs to the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase family and plays a role in the calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase cascade. In this study, quercetin activated CaMKKβ phosphorylation without affecting the intracellular calcium concentration, although CaMKKβ is closely linked to Ca2+/calmodulin. Notably, calcium increases glucose uptake by muscle cells via both CaMKKβ/AMPK-dependent and -independent mechanisms37. Moreover, androgen, ghrelin, and AMP/ATP are also involved in CaMKKβ phsophorylation38,39. Because we did not address the mechanism by which quercetin activated CaMKKβ, further study is needed to clarify this issue.

Isorhamnetin at 1 nM and 10 nM principally activated the JAK/STAT pathway to induce GLUT4 translocation (Fig. 6). The JAK/STAT-pathway is important during carcinogenesis, in particular metastasis11,12. Our finding is the first report demonstrating the involvement of JAK2 and STAT3/5 phosphorylation in the promotion of GLUT4 translocation induced by isorhamnetin in skeletal muscle cells (Fig. 7C). This result is at least partially consistent with a previous report showing that IL-15 increased glucose uptake and induced GLUT4 translocation through JAK3/STAT3 signalling11. Isorhamnetin at 0.1 nM–10 nM induced JAK2 phosphorylation, while its downstream factors STAT3 and STAT5 were phosphorylated by isorhamnetin at 10 nM and 1 nM, respectively (Fig. 6C). One conceivable reason for this observation is that JAK2 regulates STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 by different mechanisms, as leptin repressed the JAK2-STAT3/PI3K pathway in a rat model, while growth hormone regulated the phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT5 in flounder40,41. Notably, 0.1 nM isorhamnetin also induced PI3K phosphorylation, but this was not reflected in its downstream targets, such as Akt and GLUT4 translocation (Fig. 4B). One possible explanation involves the SH2B domain, which connects the JAK/STAT and insulin signalling pathways40,42,43. Indeed, the SH2B domain is reportedly involved in phosphorylation of JAK2, IRS1, IRS2, and PI3K in response to leptin41. In addition, PTP1B, a negative regulator of insulin and JAK/STAT signalling pathways, also has the potential to cause this condition44. Fudan-Yueyang Ganoderma lucidum extract has been reported to decrease blood glucose level and ameliorate insulin resistance by decreasing PTP1B expression and increasing PI3K phosphorylation44.

Furthermore, 10 nM quercetin activated phosphorylation of IRS1, PI3K, and two amino acid residues on Akt (Thr308 and Ser473), suggesting that quercetin acted in the same manner as insulin by completely activating the function of Akt to regulate glucose levels (Fig. 4). IR was not involved in quercetin- and isorhamnetin-induced GLUT4 translocation, although IRS1, PI3K, and Akt phosphorylation were activated by 10 nM quercetin in L6 myotubes (Fig. 4A). A similar result was reported for adenosine, which increased glucose uptake via its A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR), instead of IR, in skeletal muscle cells45. The possible mechanism may involve a G protein-coupled receptor, which can participate in several processes and contribute to the activation of several response element-binding proteins and transcription factors, such as activation of PI3K/Akt signalling46,47. Indeed, a quercetin- and oleic acid-responsive G-protein-coupled receptor capable of modulating insulin secretion has been reported48. In addition, differential sensitivity of factors is likely to underlie why 1 nM quercetin activated PI3K phosphorylation without activating IRS1 and Akt phosphorylation49. This condition was similar to our previous research showing that propolis extract at 10–103 ng/mL induced PI3K phosphorylation rather than aPKC phosphorylation, which is a downstream factor of PI3K14. Furthermore, PKCζ/λ was also phosphorylated by 10 nM quercetin (data not shown). Meanwhile, quercetin at a high concentration range (1 μM and 10 μM) also induced AMPK phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 2), consistent with previous results38.

In this study, quercetin at 0.1, 1, and 10 nM induced GLUT4 translocation in myotubes (Fig. 3A); nevertheless, only 0.1 nM and 1 nM quercetin increased glucose uptake (Fig. 2), indicating that GLUT4 translocation does not completely correlate with increased glucose uptake. Although GLUT4 is an essential factor for regulating glucose homeostasis, phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is required for function of GLUT4 after translocation to the plasma membrane to promote glucose uptake50. Indeed, inactivation of p38 MAPK decreased glucose uptake without affecting GLUT4 translocation51. Quercetin at 10 nM is likely to inactivate p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Furthermore, intracellular delivery of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate is another possible factor, as previous research has demonstrated that PI(3,4,5)P3 ameliorates GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane without increasing glucose uptake52. Moreover, SOCS3, SHP1, SHP2, and IRS2 also reportedly promote GLUT4 translocation without increasing glucose uptake53–55. Therefore, some discrepancies between GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake exist.

Our in vivo results revealed that quercetin at the physiological concentration range promoted GLUT4 translocation without altering the expression level of GLUT4 in muscle of mice 90 min after a single oral administration of EMIQ at 10 and 100 mg/kg body weight (Fig. 8B). Although EMIQ, which derives from rutin via enzymatic hydrolysis and contains a water soluble glucoside56, is not a natural product, it has recognized to be safe (Generally Recognized as Safe: GRAS) by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S.FDA). It is reported that EMIQ was administrated up to 2.5% in diet (approximately 1600 mg/kg body weight/day) in 13-week repeated oral toxicity study in rats57. This result supported that the maximum dose of EMIQ used in this study is non-toxic. In addition, bioavailability of EMIQ is higher than that of natural quercetin glycosides29,58. Thus, we used this compound in this study. After intake quercetin glycosides, the intestinal mucosa is the mainly tissue to hydrolyze glycoside moiety and liberate aglycone form (quercetin)28. Formed quercetin is absorbed in small intestine and receive conjugation with glucuronate and/or sulfate or methylation. Isorhamnetin is one of mathylated form of quercetin. EMIQ is absorbed in mice and human as the same as quercetin glycosides from natural sources29,59. It has been reported that the plasma concentration of conjugated metabolites was increased and reached a maximal level at 90 min after intake of EMIQ in human29. Our results showed that a single oral administration of EMIQ at 10 and 100 mg/kg body weight promoted GLUT4 translocation and the concentrations of quercetin aglycone in the plasma were 4.95 ± 0.82 nM and 6.80 ± 2.00 nM, respectively. These results were fully consistent with our in vitro data using L6 myotubes, i.e., quercetin at 0.1–10 nM significantly promoted GLUT4 translocation (Fig. 3A). We could not detect isorhamnetin after administration of EMIQ at 10 and 100 mg/kg body weight, though conjugation form of isorhamnetin (Table 1). On the other hand, quercetin and its conjugated form were detected under the same conditions. Conjugation of quercetin is higher than that of isorhamnetin. These results suggest that methylation of quercetin in mice is slower than conjugation and formed isorhamnetin is rapidly received conjugation process in mice body.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the protective effects of quercetin and isorhamnetin at a physiological concentration range on glucose uptake in muscle cells. In addition, the mechanisms by which quercetin- and isorhamnetin-increased glucose uptake are different: quercetin principally activated CaMKKβ/AMPK and insulin signalling pathways, whereas isorhamnetin mainly activated the JAK/STAT pathway. Our findings reveal molecular mechanisms that support the use of quercetin and isorhamnetin as a novel therapeutic strategy for prevention and treatment of hyperglycaemia and associated disorders.

Methods

Materials

Quercetin, DMSO, acetonitrile, formic acid, and methanol were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan) and isorhamnetin was from Extrasynthese (Genay, France). AICAR, leptin, BAPTA-AM, resazurin, 2-deoxyglucose (2DG), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), sulfatase from abalone entrailsand (Type VIII), and β-glucuronidase from Escherichia coli (Type IX-A) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Diaphorase and ß-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (ß-NADP+) were from Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Blocking-One and Blocking One-P solutions were from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was from GE Healthcare (Fairfield, WA, USA). Minimum essential medium (MEM) was from Nissui Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan). Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Tokyo, Japan). Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Reduced serum medium (Opti-MEM) and STO-609 were procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA. For western blotting analysis, anti-GLUT4 mouse IgG, anti-Akt rabbit IgG, anti-phospho-AMPKα (Thr 172) rabbit IgG, anti-AMPKα rabbit IgG, anti-JAK2 rabbit IgG, anti-phospho-JAK2 rabbit IgG, anti-STAT3 mouse IgG, anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr 705) rabbit mAb, anti-mouse IgG, and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-STAT1, anti-STAT1 (phospho Y701), anti-STAT5a, and anti-STAT5a (phospho Y694) antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-IRS1 rabbit IgG antibody was from Upstate Cell Signaling Solution (Lake Placid, NY). Anti-phospho-IRS1 (phospho Y896) and anti-phospho-tyrosine mouse mAb antibodies were from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Diego, CA). Anti-IR rabbit IgG, anti-ß-actin rabbit IgG, anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308) rabbit IgG and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) rabbit IgG were from sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). For AMPKα, JAK2, and JAK3 knockdown assay, the following siRNAs were used: 5′-GCA UAU GCU GCA GGU AGA-3′ and 5′-UCU ACC UGC AGC AUA UGC-3′ for AMPKα1 and AMPKα2, respectively; 5′-CCA CCC AAU CAU GUC UUC CAC AUA G-3′ and 5′-CUA UGU GGA AGA CAU GAU UGG GUG G-3′ for JAK2; 5′-GCU GGC AUU CUG GAC UGC AAG UAG A-3′ and 5′-UCU ACU UGC AGU CCA GAA UGC CAG C-3′ for JAK3 and 5′-AUU CUA UCA CUA GCG UGA CUU-3′ for the control.

Cell culture and treatment

In vitro cultured cell experiments were conducted according to a previously described protocol6,14. Briefly, L6 myoblasts derived from rat skeletal muscle and of less than 40 passages were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere condition of 5% CO2 and 95% air. In each experiment, cells (2.2 × 104 cells/ml) were seeded into 96-well plates or 60-mm dishes for induction of differentiation into mature myotubes. After reaching confluence, cells were supplemented with differentiation medium containing 2% FBS and the same antibiotics for 7 days. Cells were used for each experiment after morphological analysis of differentiation status using phase-contrast microscopy. To explore the contribution of CaMKKβ or intracellular-free calcium ions in quercetin- and isorhamnetin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation, L6 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 μM STO-609 and 25 μM BADPA-AM, respectively, for 30 min prior to treatment with either quercetin or isorhamnetin.

Animal treatment

All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines for animal experiments at Kobe University Animal Experimentation Regulation and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committed of Kobe University (Permission 29-05-02). Male ICR mice (5 weeks old, n = 20) were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and maintained at constant temperature (23 ± 2 °C) with a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 8:00 am). Mice were subsequently randomly divided into four groups of five each, and acclimatized for 1 week with free access to tap water and a laboratory-purified diet (3.850 kcal/g diet) consisting of 76% carbohydrate, 15% protein and 9% fat) (Research Diets, Tokyo, Japan). For analysis of concentrations of quercetin and isorhamnetin in the plasma and GLUT4 translocation in the muscle, mice were orally administrated EMIQ at 10, 100, or 1000 mg/kg body weight, or water as a vehicle control after 18 h fasting. The mice were sacrificed 90 min after the administration under anesthesia using sodium pentobarbital and seroflurane, and euthanized by exsanguination from cardiac puncture. Plasma and soleus muscle were collected, and kept at -80 °C until use.

Measurement of quercetin and isorhamnetin in the plasma of mice orally administrated EMIQ

To determine the levels of quercetin and isorhamnetin after administration of EMIQ, the obtained plasma were analyzed using HPLC (UV 370 nm) with or without deconjugation treatment using glucuronidase/sulfatase16. Briefly, an aliquot of 250 μl of plasma was mixed with 50 μl of 20% (w/v) ascorbic acid and incubated with 125 μl of 75 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) with or without 500 U/sample β-glucronidase and 125 μl of 200 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) with or without 10 U/sample sulfatase for 2 h at 37 °C after adding 2 μl of 1 mM nobiletin as an internal standard. To separate quercetin and isorhamnetin, mixture was applied on a Sep-Pak C18 1 cc Vac Cartridge and eluted with 2 ml 95% (v/v) methanol. After eluate was dried by evaporation, dried material was dissolved in 50 μl of 50% (v/v) methanol and applied to HPLC. HPLC was performed using a SHIMADZU LabSolutions system (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) with SPD-M20A diode array detector. HPLC separation was done with a gradient system using 0.02% aqueous phosphoric acid as mobile phase A and acetonitrile as mobile phase B with a Cadenza CL-C18 column (φ 4.6 mm × 250 mm, Kyoto, Japan) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The gradient program was 0–13 min, 20% B, 13–33 min, 50–80% B, 33–43 min, 100% B, 43–60 min, 20% B.

Glucose uptake assay

After serum starvation by incubating L6 myotubes in MEM with 0.2% BSA for 18 h, cells were treated with quercetin and isorhamnetin at the specified concentration (0.01 nM–10 μM) for 4 h in 0.2% BSA-containing medium. DMSO and insulin (100 nM) were used as a vehicle control and positive control, respectively. Glucose uptake was measured by an enzymatic 2DG uptake assay using myotubes on a 96-well plate as previously described60.

Preparation of whole protein and plasma membrane fractions

For in vitro cell culture experiments, after serum starvation for 18 h, myotubes were treated with various concentrations of quercetin or isorhamnetin (0.1–10 nM) for 15 min; DMSO (final 0.1%) was used as a vehicle control. As positive controls, 100 nM insulin, 1 mM AICAR, 10 nM leptin, or 100 ng/mL IL-15 were used for insulin, AMPK, JAK2/STAT, or JAK3/STAT signalling pathways, respectively. Cells were treated with insulin or AICAR for 15 min, leptin for 60 min, or IL-15 for 24 h. Whole protein and plasma membrane fractions were prepared from myotubes, as previously described61. For in vivo experiment, plasma membrane fraction and tissue lysate of soleus muscle were prepared61.

Western blot analysis

Translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane, as well as expression and phosphorylation levels of GLUT4-related regulators were estimated by western blot analysis. Briefly, equal amounts of proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Separated proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and nonspecific binding sites were blocked using either Blocking One (to detect unphosphorylated proteins) or Blocking One-P (to detect phosphoproteins). The membrane was incubated overnight with an appropriate primary antibody for GLUT4 (1:5000), IR (1:10000), p-IRS1 (1:5000), IRS1 (1:5000), p-PI3K (1:5000), PI3K (1:10000), p-Akt (1:5000), Akt (1:10000), p-AMPKα (1:5000), AMPKα (1:10000), p-ACC (1:5000), ACC (1:10000), p-LKB1 (1:5000), LKB1 (1:10000), p-JAK2 (1:5000), JAK2 (1:5000), p-JAK3 (1:5000), JAK3 (1:10000), p-STAT1 (1:5000), STAT1 (1:10000), p-STAT3 (1:5000), STAT3 (1:10000), p-STAT5 (1:5000), STAT5 (1:10000), or β-actin (1:20000), and subsequently treated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:50000) for 1 h. Specific immune complexes were developed using ImmunoStar® LD and detected with an ATTO Light-Capture II Western Blotting Detection System. Individual band density was calculated by ImageJ and normalized to the control.

Immunoprecipitation

Aliquots of whole protein fractions (100 μg protein) were incubated with anti-IR antibody (1:100) in a rotator for 2 h at 4 °C. Next, 10 μl of protein A/G plus-agarose beads were added to the reaction mixture and incubated with rotation overnight at 4 °C. The pellet, which was combined with cell lysate, specific antibody, and agarose resin, was used for SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis.

siRNA transfections

Mature myotubes were cultured in antibiotic-free medium and transfected with siRNA at a final concentration of 50 nM using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, mature myotubes were transfected with siRNA in Opti-MEM for 48 h. Subsequently, the medium was changed to fresh Opti-MEM and cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of quercetin or isorhamnetin.

Statistical analysis

Data represent mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Dunnett, Student’s t or Tukey–Kramer multiple-comparison tests. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05 using JMP 11.2.0.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17H00818 (H.A., and Y.Y.) and Creation of Innovative Centres for Research Areas (Innovative Bioproduction Kobe) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author Contributions

H.A., Y.Y., K.C. and H.J. conceived and designed the experiments; H.J. and A.N. performed the experiments; H.J. and H.A. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-38711-7.

References

- 1.Ali R, et al. Are we telling the diabetic patients adequately about foot care? J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2016;28:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhalima K, et al. Type 2 diabetes in younger adults: clinical characteristics, diabetes-related complications and management of risk factors. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Bassossy HM, et al. Geraniol alleviates diabetic cardiac complications: effect on cardiac ischemia and oxidative stress. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao L, et al. Amelioration of intracellular stress and reduction of neural tube defects in embryos of diabetic mice by phytochemical quercetin. Sci Rep. 2016;6:e21491. doi: 10.1038/srep21491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashita Y, Okabe M, Natsume M, Ashida H. Cacao liquor procyanidin extract improves glucose tolerance by enhancing GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Nutr Sci. 2012;1:e2. doi: 10.1017/jns.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawada K, Yamashita Y, Zhang T, Nakagawa K, Ashida H. Glabridin induces glucose uptake via the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway in muscle cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;5:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharya S, Dey D, Roy SS. Molecular mechanism of insulin resistance. J Biosci. 2007;32:405–413. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu W, et al. Biphasic effects of chronic ethanol exposure on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in primary cultured rat skeletal muscle cells: role of the Akt pathway and GLUT4. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:47–53. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojuka EO, Goyaram V, Smith JA. The role of CaMKII in regulating GLUT4 expression in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:322–331. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00091.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockl KSC, et al. Skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise training-AMP activated protein kinase mediates muscle fiber type shift. Diabetes. 2007;56:2062–2069. doi: 10.2337/db07-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krolopp JE, Thornton SM, Abbott MJ. IL-15 activates the JAK3/STAT3 signaling pathway to mediate glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells. Front Physiol. 2016;7:e00626. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amoyel M, Anderson AM, Bach EA. JAK/STAT pathway dysregulation in tumors: a drosophila perspective. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;28:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin L, et al. STAT3 signaling pathway is necessary for cell survival and tumorsphere forming capacity in ALDH+/CD133+ stem cell-like human colon cancar cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;416:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda M, Hayashibara K, Ashida H. Propolis extract promotes translocation of glucase transporter 4 and glucose uptake through both PI3K- and AMPK-dependent pathways in skeletal muscle. Biofactors. 2013;39:457–466. doi: 10.1002/biof.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda M, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate promotes GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:286–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamashita, Y. et al. Procyanidin promotes translocation of glucose transporter 4 in muscle of mice through activation of insulin and AMPK signaling pathways. PLoS One. 0161704 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Arias N, et al. A combination of resveratrol and quercetin induces browning in white adipose tissue of rats fed an obesogenic diet. Obesity. 2017;25:111–121. doi: 10.1002/oby.21706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, et al. Quercetin induces protective autophagy and apoptosis through ER stress via the p-STAT3/Bcl-2 axis in ovarian cancer. Apoptosis. 2017;22:544–557. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu S, et al. Isorhamnetin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in breast cancer via Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase signaling pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:6745–6751. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruan Y, Hu K, Chen H. Autophagy inhibition enhances isorhamnetin-induced mitochondria-dependent a poptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5796–5806. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roslan J, Giribabu N, Karim K, Salleh N. Quercetin ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in the heart of streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced adult male diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;86:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burak C, et al. High plasma quercetin levels following oral administration of an onion skin extract compared with pure quercetin dihydrate in humans. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:343–353. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khor CM, Nq WK, Chan KP, Dong Y. Preparation and characterization of quercetin/dietary fiber nanoformulations. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;161:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, et al. Phytic acid enhances the oral absorption of isorhamnetin, quercetin, and kaempferol in total flavones of Hippophae rhamnoides L. Fitoterapia. 2014;93:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiménez L, et al. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailavility. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao G, et al. Effects of solid dispersion and self-emulsifying formulations on the solubility, dissolution, permeability and pharmacokinetics of isorhamnetin, quercetin and kaempferol in total flavones of Hippophae rhamnoides L. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2013;39:1037–1045. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2012.699066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyer J, Brown D, Liu R. In vitro digestion and lactase treatment influence uptake of quercetin and quercetin glucoside by the Caco-2 cell monolayer. Nutr J. 2005;4:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arts IC, Sesink AL, Faassen-Peters M, Hollman PC. The type of sugar moiety is a major determinant of the small intestinal uptake and subsequent biliary excretion of dietary quercetin glycosides. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:841–847. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murota K, et al. alpha-Oligoglucosylation of a sugar moiety enhances the bioavailability of quercetin glucosides in humans. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Formica JV, Regelson W. Review of the biology of quercetin and related bioflavonoids. Food Chem Toxicol. 1995;12:1061–1080. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer JP, et al. The small intestine can both absorb and glucuronidate luminal flavonoids. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:224–230. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Leary KA, et al. Metabolism of quercetin-7-and quercetine-3-glucuronides by an in vitro hepatic model:the role of human β-glucuronidase, sulfotransferase, catechol-O-methyltransferase and multiresistant protein 2 (MRP2) in flavonoid metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:479–491. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon YJ, Wang L, DiCenzo R, Morris ME. Quercetin pharmacokinetics in humans. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2008;29:205–217. doi: 10.1002/bdd.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park KH, et al. Enhancement of solubility and bioavailability of quercetin by inclusion complexation with the cavity of mono-6-deoxy-6-aminoethylamino-β-cyclodextrin. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2017;38:880–889. doi: 10.1002/bkcs.11192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loftssona T, Duchêne D. Cyclodextrins and their pharmaceutical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2007;32:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ai-zoairy R, et al. Serotonin improves glucose metabolism by serotonylation of the small GTPase Rab4 in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13098-016-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Öberg A, et al. Shikonin increases glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells and improves plasma glucose levels in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhanya R, Arya AD, Nisha P, Jayamurthy P. Quercetin, a lead compound against type 2 diabetes ameliorates glucose uptake via AMPK pathway in skeletal muscle cell line. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:e00336. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karacosta LG, et al. A regulatory feedback loop between Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2) and the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:24832–24843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.370783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvalheira JB, Ribeiro EB, Folli F, Velloso LA, Saad MJ. Interaction between leptin and insulin signaling pathways differentially affects JAK-STAT and PI-3-kinase-mediated signaling in rat liver. Biol Chem. 2003;384:151–159. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuentes EN, et al. Inherent growth hormone resistance in the skeletal muscle of the fine flounder is modulated by nutritional status and is characterized by high contents of truncated GHR, impairment in the JAK2/STAT5 signaling pathway, and low IGF-I expression. Endocrinology. 2012;153:283–294. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan C, Li M, Rui L. SH2-B promotes insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1)- and IRS2-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in response to leptin. Biol Chem. 2004;42:43684–43691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408495200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, et al. Intramuscular injection of exogenous leptin induces adiposity, glucose intolerance and fatty liver by repressing the JAK2-STAT3/PI3K pathway in a rat model. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2017;252:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z, et al. A novel PTP1B inhibitor extracted from Ganoderma lucidum ameliorates insulin resistance by regulating IRS1-GLUT4 cascades in the insulin signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2018;9:397–406. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01489A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshioka Y, et al. Adenosine isolated from grifola gargal promotes glucose uptake via PI3K and AMPK signaling pathways in skeletal muscle cells. J Funct Foods. 2017;33:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.03.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz K, Linden J. International unin of pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacological Review. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Müller CE. International unin of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors – an update. Pharmacological Review. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badolato M, et al. Quercetin/oleic acid-based G-protein-coupled receptor 40 ligands as new insulin secretion modulators. Future Med Chem. 2017;16:1873–1885. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Alessandris C, Lauro R, Presta I, Sesti G. C-reactive protein induces phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on Ser307 and Ser 612 in L6 myocytes, thereby impairing the insulin signalling pathway that promotes glucose transport. Diabetologia. 2007;50:840–849. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0522-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niu W, et al. Maturation of the regulation of GLUT4 activity by p38 MAPK during L6 cell myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17953–17962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sweeney G, et al. An inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase prevents insulin-stimulated glucose transport but not glucose transporter translocatin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and L6 myotubes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10071–10078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shisheva A. Regulating Glut4 vesicle dynamics by phosphoinositide kinases and phosphoinositide phosphatases. Front Biosci. 2003;8:945–967. doi: 10.2741/1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartoe JL, Nathanson NM. Independent roles of SOCS-3 and SHP-2 in the regulation of neuronal gene expression by leukemia inhibitory factor. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;107:108–119. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00452-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ijuin T, Takenawa T. SKIP negatively regulates insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation and membrane ruffle formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1209–1220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1209-1220.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sasaki-Suzuki N, et al. Growth hormone inhibition of glucose uptake in adipocytes occurs without affecting GLUT4 translocation through an insulin receptor substrate-2-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6061–6070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808282200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohara A, et al. Enzymatically modified isoquercitrin supplementation intensifies plantaris muscle fiber hypertrophy in functionally overloaded mice. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14:32–39. doi: 10.1186/s12970-017-0190-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tamano S, et al. 13-Week oral toxicity and 4-week recovery study of enzymatically modified isoquercitrin in F344/DuCrj rats. Jpn. J. Food Chem. 2001;8:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makino T, et al. Enzymatically modified isoqquercitrin, α-Oligoglucosyl quercetin 3-O-glucoside, is absorbed more easily than other quercetin glycosides or aglycone after oral administration in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009;32:2034–2040. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Németh K, et al. Deglycosylation by small intestinal epithelial cell beta-glucosidases is a critical step in the absorption and metabolism of dietary flavonoid glycosides in humans. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00394-003-0397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamamoto N, Kawasaki K, Kawabata K, Ashida H. An enzymatic fluorimetric assay to quantitate 2-deoxyglucose and 2-deoxyglucose-6-phaophate for in vitro and in vivo use. Anal biochem. 2010;404:238–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishiumi S, Ashida H. Rapid preparation of a plasma membrane fraction from adipocytes and muscle cells: application to detection of translocated glucose transporter 4 on the plasma membrane. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:2343–2346. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.