Abstract

The present study aimed to identify the genes and underlying mechanisms critical to the pathology of spinal cord injury (SCI). Gene expression profiles of spinal cord tissues of trkB.T1 knockout (KO) mice following SCI were accessible from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Compared with trkB.T1 wild type (WT) mice, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in trkB.T1 KO mice following injury at different time points were screened out. The significant DEGs were subjected to function, co-expression and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analyses. A total of 664 DEGs in the sham group and SCI groups at days 1, 3, and 7 following injury were identified. Construction of a Venn diagram revealed the overlap of several DEGs in trkB.T1 KO mice under different conditions. In total, four modules (Magenta, Purple, Brown and Blue) in a co-expression network were found to be significant. Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C (PTPRC), coagulation factor II, thrombin (F2), and plasminogen (PLG) were the most significant nodes in the PPI network. ‘Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis’ and ‘complement and coagulation cascades’ were the significant pathways enriched by genes in the PPI and co-expression networks. The results of the present study identified PTPRC, F2 and PLG as potential targets for SCI treatment, which may further improve the general understanding of SCI pathology.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, differentially expressed genes, weighted correlation network analysis, protein-protein interaction, significant nodes

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a disabling condition with significant morbidity and mortality, that affects ~11,000 individuals annually worldwide (1). The mean age for patients with SCI is 33 years worldwide, and the incidence of SCI is approximately four times higher among males (2). Spinal cord damage may result in pain and paralysis, as well as loss of sensation and physical function. The causes of SCI are varied and include accidents, falls, infections and tumors (3). In addition, patients with SCI may develop spondylosis, a common degenerative change in the cervical spine (4) and its incidence has increased over the past several decades, but management strategies to reduce SCI prevalence have not yet been developed.

The current management strategies for SCI are limited. A better understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying the disease may lead to the identification of novel interventions. A study exploring the mechanisms underlying SCI has reported that overexpression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) promotes neuron regeneration and functional recovery following SCI (5). In addition, connexin 43 (Cx43) expression has been demonstrated to aggravate secondary injury following SCI, leading to researchers proposing connexins as potential targets for SCI treatment (6).

Tropomyosin-related kinase B.T1 (trkB.T1), which is highly expressed in the nervous system of adult mammals, has been identified to accumulate in astrocytes, white matter and ependymal cells following SCI (7,8). Although trkB.T1 lacks a kinase activation domain, it is active in signal transduction (9,10). Wu et al (11) performed whole genome analysis for trkB.T1 knockout (KO) mice and reported that trkB.T1 serves a critical role in SCI pain and progression by regulating pathways associated with the cell cycle (11).

Herein, a bioinformatic approach was used to analyze the microarray data compiled by Wu et al (11), in order to further investigate the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in trkB.T1 KO mice at different time points following SCI. As genes with differential expression may be closely associated with SCI pathogenesis, the functions and interactions of the identified DEGs were explored. In addition, the present study aimed to identify potential target genes and their involvement in the biological functions underlying SCI pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Spinal cord tissues of SCI mice were profiled based on the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array platform (11). Microarray data were provided by Wu et al (11); these data were generated from trkB.T1 KO and trkB.T1 wild type (WT) mice under different conditions, including sham operations, and at days 1, 3, and 7 following SCI. This dataset (GSE47681) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Data preprocessing and DEG analysis

Differences in gene expression between trkB.T1 KO and trkB.T1 WT mice in sham groups (sham KO vs. sham WT) and in SCI groups at days 1, 3, and 7 after injury (day 1 KO vs. day 1 WT; day 3 KO vs. day 3 WT; and day 7 KO vs. day 7 WT) were respectively compared via unpaired t-tests using the R package ‘limma’ (12). Genes for which met the P<0.05 and |log2 fold change (FC)|≥0.4 cutoff points were selected as DEGs, following which gene expression profiles of DEGs were visualized via the ‘gplots’ in R package version 3.0. 1 (13).

Venn diagram analysis

In order to mine the feature genes from different datasets, a Venn diagram analysis was conducted using VennPlex version 1.0.0.2 software (www.irp.nia.nih.gov/bioinformatics/vennplex.html) (14). The DEGs and their respective log2FC values were uploaded to the VennPlex version 1.0.0.2 tool, from which differences in the expression levels of DEGs at several time points were obtained, and the number of upregulated, downregulated and contraregulated genes were calculated.

Co-expression module and functional analysis

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) was used to identify highly correlated genes based on gene expression patterns across the microarray samples (15). DEGs in trkB.T1 KO mice of the sham group and SCI groups at days 1, 3 and 7 following injury were subjected to co-expression analysis using the R package ‘WGCNA’ version 1.19 (15) based on the WGCNA algorithm. Significant gene co-expression modules were screened out using the clustering method. The |correlation coefficient|≥0.65 and P<0.05 were set as the cutoff values.

Gene Ontology (GO) (16) function and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (17) pathway analyses were conducted for the genes in the co-expression modules by the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) online tool (18) with new fuzzy classification algorithms. GO and KEGG terms with counts ≥2 and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Protein-protein interaction network

PPI network analysis was performed to analyze the functional interactions between proteins encoded by DEGs associated with the co-expression network. the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (19) includes an extensive list of protein interacting pairs collected from neighborhood, gene fusion, co-occurrence, co-expression experiments, databases and text mining. Genes from the co-expression network were input into the STRING online tool to identify highly associated gene pairs. The protein pairs with medium confidence (≥0.4) were collected and the PPI network was visualized using the package ‘Cytoscape’ version 3 (20). Significant nodes with high degrees of connectivity were screened out.

Module analysis

PPI networks contain several densely connected network modules, with genes in each module commonly involved in the same biological processes. ClusterONE (21) is a graph-clustering algorithm that incorporates weighted graphs and readily generates overlapping clusters (www.paccanarolab.org/cluster-one/). As such, ClusterONE version 1.0 was used to cluster the PPI network, with P<1×10−4 set as the threshold value. Further KEGG pathway analysis of the module genes was subsequently undertaken to identify the significant pathways (P<0.05).

Results

Differential expression analysis

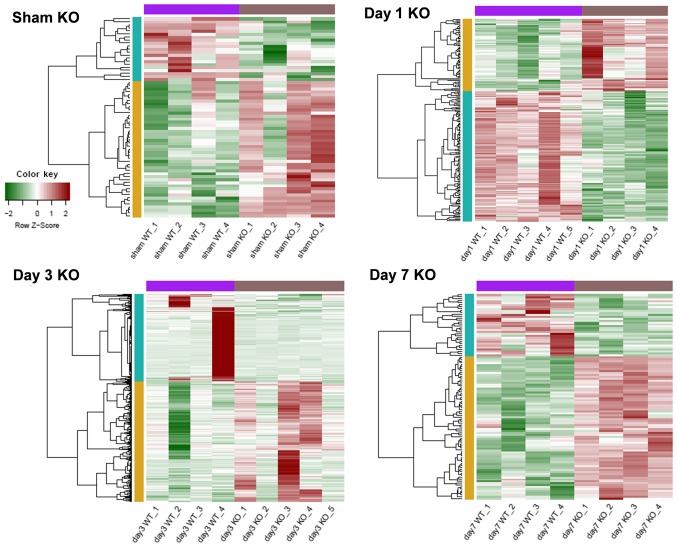

Based on P<0.05 and |log2FC| ≥0.4, DEGs of trkB.T1 KO mice in the sham, day 1, day 3 and day 7 SCI groups were respectively identified. As presented in Table I, the smallest number of DEGs occurred in the sham group, consisting of 45 upregulated and 21 downregulated genes. The day 3 SCI group contained the largest number of differentially expressed genes, consisting of 206 upregulated and 149 downregulated genes. Gene expression profiles of the various DEGs in the different groups are presented in Fig. 1. This analysis suggested that DEG expression levels may be used to distinguish between trkB.T1 KO and WT samples.

Table I.

Differentially expressed genes in the sham and spinal cord injury groups.

| Group | Upregulated gene count | Mean value logFC (up) | Downregulated gene count | Mean value logFC (down) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham KO | 45 | 0.882 | 21 | −0.5569 | 66 |

| Day 1 KO | 73 | 0.7096 | 132 | −0.6407 | 205 |

| Day 3 KO | 206 | 0.6201 | 149 | −0.8843 | 355 |

| Day 7 KO | 74 | 0.54 | 32 | −0.5852 | 106 |

KO, knockout; FC, fold change.

Figure 1.

Heat map of the differentially expressed genes in trkB.T1 KO mice following injury at different time points. Red represents relatively high levels of expression; green represents relatively low levels of expression. Purple and brown bars indicated the trkB.T1 WT samples and trkB.T1 KO samples, respectively; yellow and blue bars indicated that upregulated and downregulated genes respectively in trkB.T1 KO mice following injury. The heat map demonstrated that the samples from trkB.T1 KO were distinct from those from the trkB.T1 WT mice. KO, knockout; WT, wild type.

Venn diagram analysis

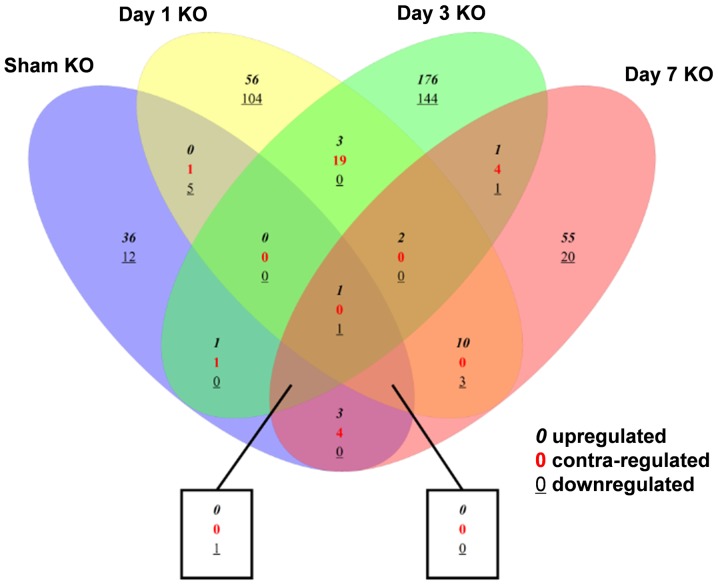

The relationships between the different DEG groups are depicted in Fig. 2. Compared with the sham group, the number of overlapping DEGs of trkB.T1 KO mice at days 1, 3 and 7 after SCI were 7, 5 and 10, respectively. In addition, 26 DEGs overlapped between the day 1 and day 3 SCI groups; 17 overlapped between the day 1 and day 7 SCI groups; and 11 overlapped between the day 3 and day 7 SCI groups.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of the differentially expressed genes among the different groups. KO, knockout.

WGCNA co-expression analysis

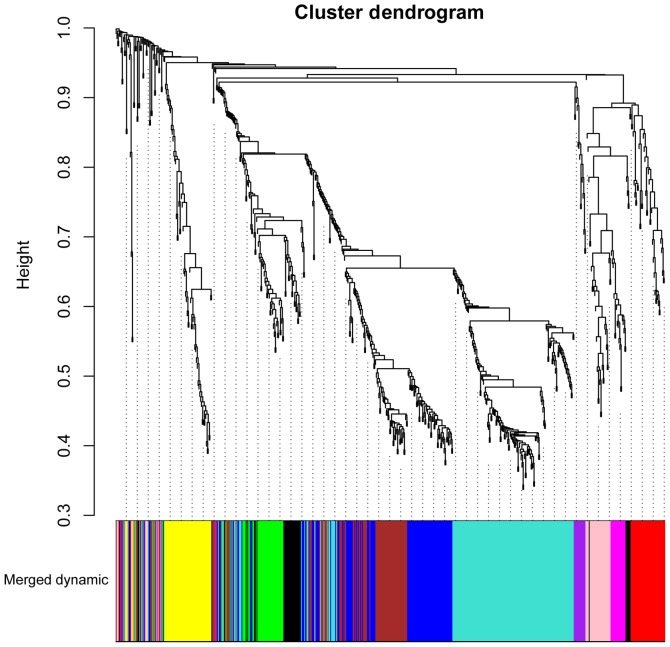

A total of 664 DEGs in the sham group and SCI groups at days 1, 3, and 7 following injury were identified in trkB.T1 KO mice. Subjecting the DEGs to WGCNA analysis revealed that they were clustered into 11 modules (represented by the different colors in Fig. 3). The top four modules-those with the highest correlation coefficients (CC) and lowest P-values-were, in the following order: Magenta (CC=0.66, P=3.67×10−3; gene count, 23), Purple (CC=0.65, P=4.69×10−3; gene count, 15), Brown (CC=0.9, P=7.20×10-7; gene count, 96) and Blue (CC=0.88, P=3.62×10−6; gene count, 110) modules.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering tree for genes with co-expression interactions. The branches of the dendrogram indicate the gene clusters; co-expressed modules are represented by different colors.

Functional analysis revealed that the genes in the Magenta module were significantly enriched in ‘response to virus’, ‘immune response’, and ‘cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway’; genes in the Purple module were strongly associated with ‘extracellular region’ and ‘drug metabolism’; genes in the Blue module were significantly associated with ‘immune response’, ‘Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis’ and ‘complement and coagulation cascades’; and genes in the Brown module were markedly enriched in ‘oxidation reduction’, ‘drug metabolism’ and ‘complement and coagulation cascades’ (Table II).

Table II.

Significant GO and KEGG pathways for genes in co-expression modules.

| Module | Category | Term | Count | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magenta | BP | GO:0009615~response to virus | 5 | 1.85×10−7 |

| GO:0006955~immune response | 6 | 1.07×10−5 | ||

| BP | GO:0006952~defense response | 5 | 2.09×10−4 | |

| CC | GO:0005783~endoplasmic reticulum | 5 | 5.95×10−4 | |

| MF | GO:0032555~purine ribonucleotide binding | 8 | 1.17×10−3 | |

| GO:0032553~ribonucleotide binding | 8 | 1.17×10−3 | ||

| MF | GO:0017076~purine nucleotide binding | 8 | 1.50×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | mmu04623:Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 3 | 1.84×10−3 | |

| mmu04622:RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | 3 | 2.80×10−3 | ||

| Purple | CC | GO:0044421~extracellular region part | 4 | 1.50×10−2 |

| GO:0005576~extracellular region | 5 | 2.34×10−2 | ||

| KEGG_PATHWAY | mmu00983:Drug metabolism | 2 | 4.11×10−2 | |

| Blue | BP | GO:0006955~immune response | 15 | 8.03×10−8 |

| GO:0009611~response to wounding | 11 | 9.24×10−6 | ||

| BP | GO:0001775~cell activation | 9 | 3.32×10−5 | |

| CC | GO:0034358~plasma lipoprotein particle | 4 | 4.65×10−4 | |

| GO:0032994~protein-lipid complex | 4 | 4.65×10−4 | ||

| CC | GO:0005886~plasma membrane | 28 | 3.60×10−3 | |

| MF | GO:0001871~pattern binding | 6 | 4.28×10−4 | |

| GO:0030247~polysaccharide binding | 6 | 4.28×10−4 | ||

| MF | GO:0005539~glycosaminoglycan binding | 5 | 2.46×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | mmu04666:Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis | 6 | 3.71×10−4 | |

| mmu04610:Complement and coagulation cascades | 5 | 1.28×10−3 | ||

| mmu04650:Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 5 | 7.47×10−3 | ||

| Brown | BP | GO:0055114~oxidation reduction | 10 | 2.03×10−3 |

| GO:0002526~acute inflammatory response | 4 | 4.97×10−3 | ||

| BP | GO:0055090~acylglycerol homeostasis | 2 | 8.52×10−3 | |

| CC | GO:0005576~extracellular region | 22 | 7.15×10−5 | |

| GO:0005615~extracellular space | 10 | 1.23×10−3 | ||

| GO:0044421~extracellular region part | 12 | 1.97×10−3 | ||

| MF | GO:0016712~oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen, reduced flavin or flavoprotein as one donor, and incorporation of one atom of oxygen | 4 | 9.68×10−4 | |

| GO:0009055~electron carrier activity | 6 | 1.99×10−3 | ||

| MF | GO:0043176~amine binding | 4 | 2.49×10−3 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | mmu00982:Drug metabolism | 5 | 1.04×10−3 | |

| mmu04610:Complement and coagulation cascades | 4 | 1.04×10−2 | ||

| mmu00591:Linoleic acid metabolism | 3 | 3.16×10−2 |

MF, molecular function; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

PPI construction and module analysis

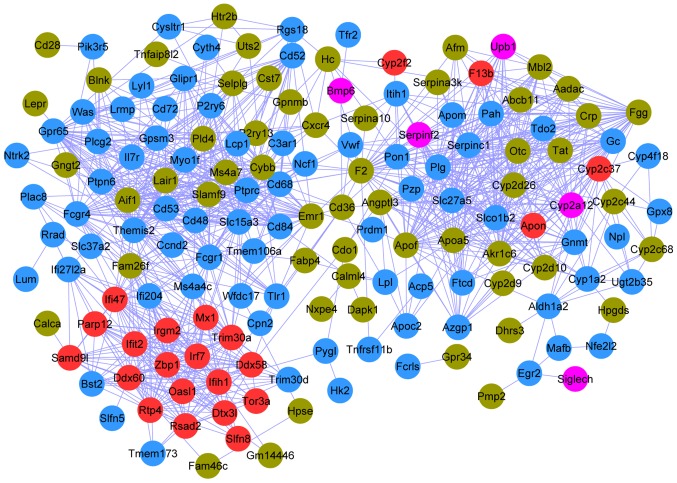

The PPI network connected 161 nodes through 1,051 edges; the color scheme used for the nodes was the same as that used for the modules described in the previous section (Fig. 4). The top 20 nodes (Table III) were determined to have a degree ≥28 in the PPI network, including protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C (PTPRC; degree, 43; Blue), coagulation factor II, thrombin (F2; degree, 41; Brown), plasminogen (PLG; degree, 38; Blue), and thymocyte selection associated family member 2 (Themis2; degree, 37; Blue).

Figure 4.

Protein-protein interaction network of the differentially expressed genes. Gene modules are represented by different colors.

Table III.

Top 20 genes with the highest degree in the PPI network.

| Gene | Module type | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| PTPRC | Blue | 43 |

| F2 | Brown | 41 |

| PLG | Blue | 38 |

| THEMIS2 | Blue | 37 |

| SERPINC1 | Blue | 35 |

| SLC27A5 | Blue | 34 |

| SLC15A3 | Blue | 33 |

| AKR1C6 | Brown | 32 |

| CD53 | Blue | 32 |

| TRIM30A | Magenta | 32 |

| PTPN6 | Blue | 32 |

| GPR65 | Blue | 32 |

| SLCO1B2 | Blue | 32 |

| APOF | Brown | 32 |

| FCGR4 | Blue | 30 |

| AIF1 | Brown | 30 |

| APOA5 | Brown | 28 |

| IFI47 | Magenta | 28 |

| FGG | Brown | 28 |

| FCGR1 | Blue | 28 |

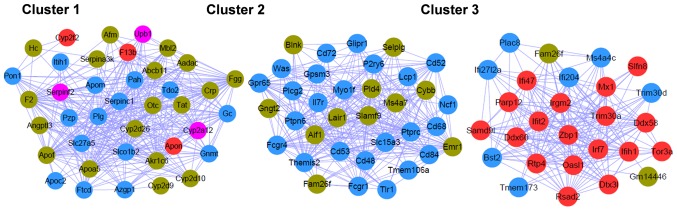

ClusterOne analysis resulted in three significant gene clusters (Fig. 5), and the DAVID online tool, which facilitates classification of functionally associated genes in different KEGG pathways (Table IV), demonstrated that the genes in cluster 1 were closely associated with ‘complement and coagulation cascades’, ‘drug metabolism’, and ‘phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis’; the genes in cluster 2 were significantly involved in ‘Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis’, ‘B cell receptor signaling pathway’ and ‘natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity’; genes in cluster 3 were involved in the ‘cytosolic DNA-sensing’ and ‘RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathways’.

Figure 5.

Significant modules of the protein-protein interaction network. Gene modules are represented by different colors.

Table IV.

Significant pathways for genes in the protein-protein interaction network.

| Cluster | Term | P-value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | mmu04610: Complement and coagulation cascades | 1.02×10−8 | F13B, MBL2, FGG, HC, SERPINF2, F2, SERPINC1, PLG |

| mmu00982: Drug metabolism | 3.15×10−3 | CYP2D9, CYP2A12, CYP2D10, CYP2D26 | |

| mmu00400: Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 1.99×10−2 | PAH, TAT | |

| Cluster 2 | mmu04666: Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis | 1.24×10−4 | PTPRC, NCF1, PLCG2, WAS, FCGR1 |

| mmu04662: B cell receptor signaling pathway | 1.28×10−3 | PTPN6, PLCG2, CD72, BLNK | |

| mmu04650: Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 4.29×10−3 | CD48, PTPN6, PLCG2, FCGR4 | |

| mmu05340: Primary immunodeficiency | 4.35×10−3 | PTPRC, IL7R, BLNK | |

| mmu04670: Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 4.23×10−2 | CYBB, NCF1, PLCG2 | |

| Cluster 3 | mmu04623: Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 8.22×10−6 | DDX58, TMEM173, IRF7, ZBP1 |

| mmu04622: RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway | 1.57×10−5 | DDX58, IFIH1, TMEM173, IRF7 |

Discussion

SCI often results in chronic pain and loss of physical function (22). A previous study demonstrated that TrkB.T1, as a receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor, serves a critical role in neuropathic pain and SCI progression (11). In the present study, the significant DEGs at different time points following SCI were identified and potential targets for SCI therapy were suggested based on the differential expression profiles induced by TrkB.T1 KO.

In total, 664 genes were differentially expressed in the sham group and SCI groups at different time points following injury. Gene expression profiles of the DEGs differed significantly between TrkB.T1 KO and TrkB.T1 WT samples, and construction of a Venn diagram indicated a lower number of overlapping DEGs under the different conditions. Based on these results, it was concluded that the DEGs screened out were significant.

Analysis of the PPI network suggested that PTPRC, F2, and PLG were the most significant nodes, with multiple interactions with other nodes, and PTPRC with a degree of 43 was identified to be the single most significant node in the PPI network. Previous research has shown PTPRC to be a critical DEG in the PPI network following spared nerve injury, and PTPRC might thus represent a potential target for peripheral neuropathic pain intervention (23). Based on the results obtained in the present study, it was speculated that PTPRC may also have a critical role in the pathology of SCI.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase, the receptor type C encoded by PTPRC, is a member of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family. PTPRC, also known as CD45 antigen, is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells in particular and is strongly associated with cellular growth and proliferation. Transplanted hematopoietic stem cells have been demonstrated to persist in SCI lesions and contribute to functional recovery following SCI (24). The expression of CD45 has been revealed to be upregulated in macrophages and microglia during the inflammatory response following SCI (25). The anti-inflammatory activation of macrophages and microglia promotes tissue and function repair following SCI (25).

In addition, PTPRC in cluster 2 was significantly enriched in Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis, a finding consistent with previous results; Jin et al (26) also reported that the genes upregulated post-SCI are significantly enriched in Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis. Furthermore, Ohri et al (27) observed that the Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis pathway is dysregulated in C/EBP-homologous protein 10-null mice following severe SCI. Previous evidence further suggests that superoxide is produced during Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis, and is strongly associated with neuronal death following SCI (28,29). In the present study, co-expression analysis also revealed that PTPRC was clustered in the Blue module, and the genes contained therein are known to be associated with Fc γ R-mediated phagocytosis. Taken together, these results suggested that PTPRC serves a critical role in SCI progression via interactions with other genes.

F2 and PLG were also identified to be critical genes in the PPI network. PPI module analysis suggested that F2 and PLG composed cluster 2, and were both significantly enriched in the complement and coagulation cascades. Co-expression analysis clustered F2 in the Brown module and PLG in the Blue module, and subsequent KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the genes in the Brown and Blue modules were closely associated with the complement and coagulation cascades, which suggested that the findings of the present study were of particular significance.

Coagulation factor II, also known as thrombin, is encoded by F2. Thrombin functions in coagulation-associated reactions and thus in reducing blood loss. Like thrombin, plasmin encoded by PLG is a serine protease present in the blood (27). It has been reported that patients with SCI are often afflicted with coagulation-related disorders, including altered platelet function and coagulation factor concentrations, which may lead to cardiovascular disorders (30,31). Therefore, focused targeting of F2 and PLG expression may aid in the mitigation of cardiovascular disorders associated with SCI.

Due to a lack of clinical materials and funding, the present study was unable to provide experimental validation of these findings, but these results warrant future research involving both cellular and clinical samples.

In conclusion, PTPRC, F2 and PLG were identified as significant nodes in the PPI network, and therefore may have critical function in SCI progression through their involvement in inflammatory responses and coagulation disorders. As such, PTPRC, F2 and PLG may be candidate targets for SCI gene therapy. The findings of the present study may lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of SCI and shed light on the identification of novel therapeutic targets. However, clinical trials on gene therapy are necessary to assess potential genetic strategies for SCI.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee program (no 16411955200) and the Scientific Research and Innovation Team Funding Plan of Shanghai Sanda University.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

LW and FH were responsible for the conception and design of the research, and drafting the manuscript. WZ performed the data acquisition. WC performed the data analysis and interpretation. BY participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Crewe NM, Krause JS. Spinal cord injury. In: Medical, Psychosocial and Vocational Aspects of Disability. In: Brodwin MG, Siu FW, Howard J, Brodwin ER, editors. 3rd. Elliott and Fitzpatrick, Inc.; Athens, GA: 2009. pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyndaele M, Wyndaele JJ. Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: What learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord. 2006;44:523–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y, Tang Y, Vogel LC, DeVivo MJ. Causes of spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2013;19:1–8. doi: 10.1310/sci1901-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah RR, Tisherman SA. Spinal cord injury. J Imaging the ICU Patient. 2014:377–380. doi: 10.1007/978-0-85729-781-5_41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang C, Bradley PM, Jacobi A, Kerschensteiner M, Bareyre FM. STAT3 promotes corticospinal remodelling and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:931–937. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C, Han X, Li X, Lam E, Peng W, Lou N, Torres A, Yang M, Garre JM, Tian GF, et al. Critical role of connexin 43 in secondary expansion of traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3333–3338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1216-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King VR, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB, Priestley JV. Changes in truncated trkB and p75 receptor expression in the rat spinal cord following spinal cord hemisection and spinal cord hemisection plus neurotrophin treatment. Exp Neurol. 2000;165:327–341. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liebl DJ, Huang W, Young W, Parada LF. Regulation of Trk receptors following contusion of the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:15–26. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorsey SG, Renn CL, Carimtodd L, Barrick CA, Bambrick L, Krueger BK, Ward CW, Tessarollo L. In vivo restoration of physiological levels of truncated TrkB.T1 receptor rescues neuronal cell death in a trisomic mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carim-Todd L, Bath KG, Fulgenzi G, Yanpallewar S, Jing D, Barrick CA, Becker J, Buckley H, Dorsey SG, Lee FS, Tessarollo L. Endogenous truncated TrkB.T1 receptor regulates neuronal complexity and TrkB kinase receptor function in vivo. J Neurosci. 2009;29:678–685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5060-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Renn CL, Faden AI, Dorsey SG. TrkB. T1 contributes to neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury through regulation of cell cycle pathways. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12447–12463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0846-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth GK. Limma: Linear models for microarray data. J Bioinform Comput Biol Solut Using R and Bioconductor. 2005:397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warnes GR, Bolker B, Bonebakker L, Gentleman R, Liaw WHA, Lumley T, Maechler M, Magnusson A, Moeller S, Schwartz M, Venables B. gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. R package version 3.0.1. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai H, Chen H, Yi T, Daimon CM, Boyle JP, Peers C, Maudsley S, Martin B. VennPlex-A novel Venn diagram program for comparing and visualizing datasets with differentially regulated datapoints. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos A, Tsafou KP, et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D447–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nepusz T, Yu H, Paccanaro A. Detecting overlapping protein complexes in protein-protein interaction networks. Nat Methods. 2012;9:471–472. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Defrin R, Ohry A, Blumen N, Urca G. Characterization of chronic pain and somatosensory function in spinal cord injury subjects. Pain. 2001;89:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang YK, Lu XB, Wang YH, Yang MM, Jiang DM. Identification crucial genes in peripheral neuropathic pain induced by spared nerve injury. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2152–2159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koda M, Okada S, Nakayama T, Koshizuka S, Kamada T, Nishio Y, Someya Y, Yoshinaga K, Okawa A, Moriya H, Yamazaki M. Hematopoietic stem cell and marrow stromal cell for spinal cord injury in mice. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1763–1767. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000183329.05994.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.David S, Kroner A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:388–399. doi: 10.1038/nrn3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin L, Wu Z, Xu W, Hu X, Zhang J, Xue Z, Cheng L. Identifying gene expression profile of spinal cord injury in rat by bioinformatics strategy. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:3169–3177. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohri SS, Maddie MA, Zhang Y, Shields CB, Hetman M, Whittemore SR. Deletion of the pro-apoptotic endoplasmic reticulum stress response effector CHOP does not result in improved locomotor function after severe contusive spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:579–588. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu W, Chi L, Xu R, Ke Y, Luo C, Cai J, Qiu M, Gozal D, Liu R. Increased production of reactive oxygen species contributes to motor neuron death in a compression mouse model of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:204–213. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueyama T, Lennartz MR, Noda Y, Kobayashi T, Shirai Y, Rikitake K, Yamasaki T, Hayashi S, Sakai N, Seguchi H, et al. Superoxide production at phagosomal cup/phagosome through βI protein kinase C during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in microglia. J Immunol. 2004;173:4582–4589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. Cardiovascular complications after acute spinal cord injury: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E13. doi: 10.3171/FOC.2008.25.11.E13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bravo G, Guízar-Sahagún G, Ibarra A, Centurión D, Villalón CM. Cardiovascular alterations after spinal cord injury: An overview. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2004;2:133–148. doi: 10.2174/1568016043477242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.