Abstract

Spinal-bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), is an X-linked motor neuron disease caused by a CAG-repeat expansion in the first exon of the androgen receptor gene (AR) on chromosome X. In SBMA, non-neural clinical phenotype includes disorders of glucose and lipid metabolism. We investigated the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS), insulin resistance (IR) and non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in a group of SBMA patients. Forty-seven consecutive patients genetically diagnosed with SBMA underwent biochemical analyses. In 24 patients abdominal sonography examination was performed. Twenty-three (49%) patients had fasting glucose above reference values and 31 (66%) patients had a homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR) ≥ 2.6. High levels of total cholesterol were found in 24 (51%) patients, of LDL-cholesterol in 18 (38%) and of triglycerides in 18 (38%). HDL-cholesterol was decreased in 36 (77%) patients. Twenty-four (55%) subjects had 3 or more criteria of MS. A positive correlation (r = 0.52; p < 0.01) was observed between HOMA-IR and AR-CAG repeat length. AST and ALT were above the reference values respectively in 29 (62%) and 18 (38%) patients. At ultrasound examination increased liver echogenicity was found in 22 patients (92 %). In one patient liver cirrhosis was diagnosed. Liver/kidney ratio of grey-scale intensity, a semi-quantitative parameter of severity of steatosis, strongly correlated with BMI (r = 0.68; p < 0.005). Our study shows a high prevalence of IR, MS and NAFLD in SBMA patients, conditions that increase the cardiovascular risk and can lead to serious liver damage, warranting pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment.

Key words: muscular atrophy, spinal-bulbar muscular atrophy, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, non alcoholic fatty liver disease

Introduction

Kennedy’s disease, also known as spinal-bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), is a rare, late-onset, X-linked motor neuron disease. It is caused by a CAG trinucleotide-repeat expansion in the first exon of the androgen receptor gene (AR) on chromosome X. The CAG sequence encodes a polyglutamine tract (polyQ), with more than 38 repeats considered to be pathogenetic (1).

SBMA affects adult males with onset usually between 30 and 50 years, and is characterized by selective motor neuron degeneration occurring in brainstem and spinal cord, leading to progressive bulbar and limb muscle weakness and atrophy (2). Besides the well-known neurological phenotype, non-neurological symptoms are common in SBMA. These include features belonging to the cluster of metabolic syndrome (MS), a condition of increased cardiovascular risk characterized by insulin resistance (IR), abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia and glucose intolerance (3). In man, hypogonadism is associated with MS, which seems to be improved by treatment with testosterone (4). Several molecular mechanisms mediated by AR signaling can lead to the development of MS (5). IR is a key pathogenic factor in both MS and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a clinicopathologic entity that includes a spectrum of liver damage ranging from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (6). As MS and NAFLD may lead to worse outcomes in patients with chronic diseases and benefit from pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment, we investigated the prevalence of MS, IR and NAFLD in a group of SBMA subjects.

Patients and methods

Forty-seven consecutive patients genetically diagnosed with Kennedy’s disease, undergoing no specific treatment for SBMA, were recruited after obtaining written informed consent. They were all Italian and followed-up in the Department of Neurosciences, University of Padua. No patients was under statin or metabolic treatment at the time of evaluation. One hundred twenty-three age-matched healthy males served as controls. For all participants, anthropometric parameters, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and laboratory data were collected. Body weight was assessed with a calibrated standard beam balance, height was measured by a standard height bar, and Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Waist circumference was measured at the midway between lower rib and crista iliaca, according to WHO recommendations (7).

Blood pressure was measured using the method recommended by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (8). Laboratory tests, measured after an overnight fast, included: fasting plasma glucose, immuno-reactive insulin, serum triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), alanine aminotranferase (ALT), aspartate aminotranferase (AST), and total serum testosterone.

To evaluate IR, homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the formula: HOMA-IR = [glucose (mmol/L) * insulin (μU/mL)/22.5], using fasting values (9). IR was defined as HOMA-IR ≥ 2.5. According to NHLBI/AHA criteria (10), MS was diagnosed when three or more of the following risk factors were present: abdominal obesity (waist circumference > 102 cm), hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 130/ ≥ 85 mmHg) or specific medication, level of triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dl (1.7 mmol/L) or specific medication, low HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dl (1.03 mmol/L) or specific medication, and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl (5.6 mmol/L) or history of diabetes mellitus or taking antidiabetic medications.

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes using the standard salting out procedure. CAG repeats were amplified by PCR as previously described (11) and repeats fragment sizing was performed on an ABI PRISM 3,700 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The specific length of CAG repeats was further verified via Sanger sequencing.

We assessed motor functions using the revised version of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R). Although this scale was not developed for SBMA, all items in this rating scale are applicable to the disease (12).

Abdominal sonography was performed in 24 subjects with SBMA, randomly chosen within the group. The exam was performed by a single skilled operator with an Hitachi HI VISION Ascendus equipment (Hitachi Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and a convex phased array transducer (5-1 MHz) after at least an 8-hours fast. All images were obtained with the same presetting of the sonographic equipment that is, imaging probe, gain, focus, and depth range. Liver steatosis was graded as follows (13):

grade I (mild): slightly increased liver brightness relative to that of the kidney with normal visualization of the diaphragm and intrahepatic vessel borders;

grade II (moderate): increased liver brightness relative to that of the kidney with slightly impaired visualization of the intrahepatic vessels and diaphragm;

grade III (severe): markedly increased liver brightness relative to that of the kidney with poor or no visualization of the intrahepatic vessel borders, diaphragm and posterior portion of the right lobe of the liver.

A semiquantitative estimate of steatosis was also obtained based on comparative analysis of digital sonographic images of the liver and right kidney (14). Briefly, US images of both organs were acquired and the grey-scale intensity of selected regions of interest was measured, and a liver/kidney (L/K) ratio was calculated, which has been shown to display direct correlation with the degree of steatosis measured by histology.

The diagnosis of NAFLD was established by ultrasonography followed by the exclusion of the secondary causes of hepatic steatosis: alcohol intake of 30 g/day or more, ingestion of drugs known to produce hepatic steatosis, a positive serology for hepatitis B or C virus, a history of another known liver disease.

Continuous variables were described as means plus or minus one standard deviation. Student’s t test was used to measure the statistical significance of the mean differences, and the relationship between two continuous variables was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The baseline characteristics, anthropometric and biochemical parameters of the SBMA patients and the healthy control subjects are summarized in Table I. Mean SBMA duration since its onset was 14.9 ± 7.0 years (range 4-30). The SBMA patients had higher waist circumference, SBP, DBP, glycate haemoglobin, IRI, HOMA-IR, AST and ALT than the controls. Twenty-four (55%) patients with SBMA had 3 or more criteria of MS.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and biochemical profile of patients with SBMA and control subjects.

| SBMA (n. 47) |

Control (n. 124) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.7 ± 7.0 | 55.3 ± 8.4 | n.s. |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5 ± 3.7 | 24.8 ± 3.4 | n.s. |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101 ± 7.5 | 98 ± 8.1 | < 0.05 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 138 ± 18 | 129 ± 13 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 90 ± 10 | 86 ± 9 | < 0.01 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 115 ± 34 | 108 ± 21 | n.s. |

| Glycate haemoglobin (mmol/mol) | 41 ± 13 | 37 ± 11 | < 0.05 |

| IRI (μU/ml) | 15.0 ± 10.7 | 8.8 ± 7.2 | < 0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.1 ± 2.5 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.36 ± 0.84 | 5.21 ± 0.76 | n.s |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.38 ± 0.42 | 1.43 ± 0.39 | n.s. |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.98 ± 1.26 | 1.72 ± 1.11 | n.s. |

| AST (U/L) | 47 ± 21 | 25 ± 11 | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 57 ± 27 | 27 ± 15 | < 0.001 |

BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; IRI: immuno-reactive insulin; HOMA-IR: insulin resistance homeostatic model assessment; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase.

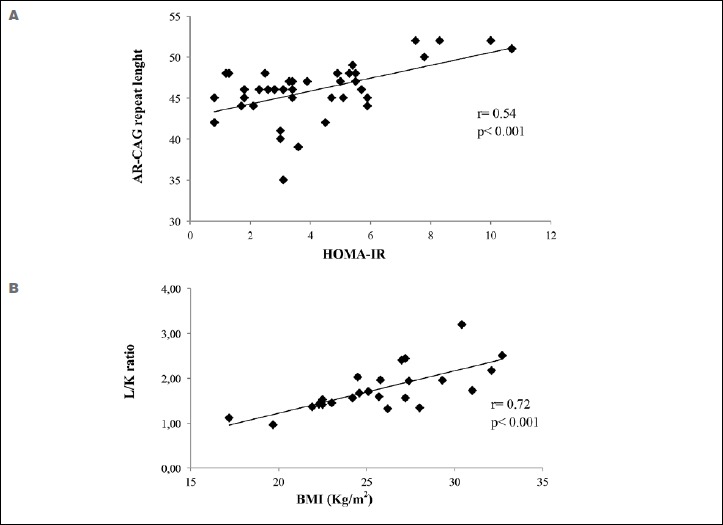

In SBMA patients a positive correlation was observed between HOMA-IR and AR-CAG repeat length (Fig. 1A). No correlation was observed between HOMA-IR and BMI, between HOMA-IR and disease duration and between HOMA-IR and ALSFRS-R. No difference in BMI was found between patients with normal and high HOMA-IR.

Figure 1.

Correlations between AR-CAG repeat length and HOMA-IR (A) and between L/K ratio and BMI (B).

AR: androgen receptor; BMI: body mass index; HOMA-IR: homeostatic model of assessment insulin resistance

AST and ALT were above the references values respectively in 29 (62%) and 18 (38%) cases. Twenty-six patients with hypertransaminasemia had an AST/ALT ratio < 1. Total serum testosterone was elevated in five patients (10%) and decreased in three (6%).

At ultrasound examination increased liver echogenicity was found in 22/24 SBMA patients. Eleven patients showed grade I, 7 patients grade II and 4 patients grade III steatosis (Table 2). One patient was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. L/K ratio strongly correlated with BMI (Fig. 1B). AR-CAG repeat length and disease duration did not correlate with L/K ratio All patients with grade III steatosis and the subject with liver cirrhosis were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Dividing patients based on the steatosis grading, the group with higher degree had a BMI significantly greater than those with a lower degree. On the contrary, no differences were observed in the AR-CAG repeat length and in the disease duration (Table 2). No significant correlation was found between total serum testosterone and other parameters.

Table 2.

BMI and AR-CAG repeat length in patients with spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy sorted by sonographic echogenicity.

| Grade of liver echogenicity: 0-1 |

Grade of liver echogenicity: > 1 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. | 12 | 12 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.5 | 28.3 ± 3.5 | < 0.01 |

| AR-CAG repeat lenght | 46 ± 4 | 49 ± 7 | n.s. |

| Disease duration (years) | 12.8 ± 3.3 | 12.6 ± 3.5 | n.s. |

BMI: body mass index; AR: androgen receptor.

Discussion

This study evidenced that SBMA patients had higher prevalence of MS criteria, IR and hypertransaminasemia than the controls. Many mechanisms related to IR and MS, such as hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure and inflammation, can accelerate atherosclerosis and increase the risk of vascular complications (15).

Recently, a high prevalence of IR in SBMA patients was reported by Nakatsuji et al. (16). The authors described a correlation between motor function, evaluated with ALSFRS-R, and HOMA-IR that in our patients was not found. This discrepancy can be partly due to ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity observed between Caucasian and Asian peoples (17).

Hypertransaminasemia was frequently observed in our SBMA patients. Both AST and ALT are present in skeletal muscle, with ALT being more specific to the liver (18). These data suggest a liver involvement in SBMA patients. To characterize this, NAFLD was found in 92% of SBMA patients undergoing abdominal sonography. NAFLD is strictly related to IR, and linked to MS. Its global prevalence is 25% (19). Even if NAFLD is frequently a benign condition, it can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (20). Although most of studied subjects had a mild or moderate steatosis, 4 patients had a severe fatty liver and in one patient hepatic involvement had evolved to micronodular cirrhosis. In this patient, MS and liver abnormalities were diagnosed several years before the onset of Kennedy’s disease. In SBMA, as well as in the general population (21), obesity seems to worsen the severity of NAFLD, which can occur also in lean subjects. On the contrary, the severity of NAFLD does not appear to be related to the disease duration.

An evidence of NAFLD was recently reported by Gruber et al. (22) in nearly all SBMA patients evaluated with magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

IR is a key pathogenic factor in both NAFLD and MS. Increased adipose tissue results in increased FFA flux to tissues, including the liver, triglyceride storage and IR (23). In fatty liver, glucose uptake and insulin-mediated suppression of glucose production are impaired, exacerbating the IR.

Testosterone and androgen receptors play a pivotal role in the regulation of insulin signaling and in several aspect of MS. Epidemiological studies demonstrate an association between low levels of testosterone in men and obesity, MS and type 2 diabetes mellitus (24). In prostate cancer, androgen-deprivation therapy improves survival but it leads to severe hypogonadism with different adverse effects, including increase of fat mass and circulating insulin levels (25). Clinical studies showed that testosterone replacement can improve insulin sensitivity in hypogonadal men (26) and reduce markers of MS and inflammation in hypogonadal men with MS (27).

The CAG repeat polymorphism within the AR gene can also play a role in development of MS (28). The polymorphism of AR-CAG repeats influences insulin sensitivity and the components of MS in men (29). Evidence suggests that CAG number is inversely correlated to the transcriptional activity of AR (30). According to these data, in SBMA patients IR, evaluated by HOMA-IR, positively correlated with AR-CAG repeat length.

The mechanisms through which testosterone acts on metabolism control in man are complex. An increasing body of evidence shows that testosterone modulates the expression of important regulatory proteins involved in glycolysis, glycogen synthesis and lipid metabolism in liver, muscle and adipose tissues. The molecular basis of deficiency in AR signaling has been investigated using animal models. Male mice with global deletion of AR (GARKO) show central obesity, fasting hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, and IR (31). In the GARKO mouse model, the ability of insulin to activate the phosphatidylinositide-3 kinase, was reduced by 60% in skeletal muscle and liver, resulting in impairment of insulin signaling (32). In the selective hepatocyte deleted AR mouse (LARKO), a high-fat diet induced development of obesity, hepatic steatosis, fasting hyperglycemia and insulin resistance (32). Reduced insulin sensitivity in fat-fed LARKO mice was associated with decreased phosphoinositide-3 kinase activity and increased phosphenolpyruvate carboxykinase expression, features which can explain the impaired insulin signaling and increased hepatic glucose production (31). In testicular feminized mice, which have a non-functional AR, an elevated expression of key regulatory enzymes of fatty acid synthesis, acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha (ACACA) and fatty acid synthase, was found, explaining the increased hepatic lipid deposition compared to controls (32). Taken together, IR and elevated lipid synthesis observed in the liver of animal models with AR defect can explain the very high prevalence of NAFLD in SBMA subjects. NAFLD severity was correlated with BMI, but not with AR-CAG repeat length, suggesting that, although AR deficiency can lead to NAFLD, its severity, and, maybe, progression, is related to obesity, warranting pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. An attenuation of expression of insulin receptors in the skeletal muscle of SBMA patients has been recently reported by Nakatsuji et al., providing another possible pathomechanism of metabolic alterations (16). Instead, this study failed to find a valid association between HOMA-IR and androgen insensitivity in SBMA patients. In contrast, Guber et al. reported an increased retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4) expression in their SBMA patients, consistent with a loss of androgen stimulation (22). The increase of RBP4 plasma levels contributes to insulin-resistance and its expression is significantly increased in AR knock-out mice (33). In conclusion, this study confirm both metabolic and hepatic involvement in the SBMA patients. These alterations can be explained mainly by the reduction of testosterone activity because of polyQ expansion in AR gene and must be considered as a main characteristic of Kennedy disease. Metabolic alterations in SBMA are a suggestive model of androgen deprivation in male and require a multidisciplinary approach to disease. However, considering the conflicting data on the role of androgen stimulation in the metabolic involvement, further studies are needed to understand the pathogenesis of NAFLD and IR in SBMA patients and the possible detrimental consequences of anti-androgen approaches to disease.

References

- 1.La Spada AR, Wilson EM, Lubahn DB, et al. Androgen receptor gene mutations in X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Nature 1991;352:77-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsuno M, Tanaka F, Adachi H, et al. Pathogenesis and therapy of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA). Prog Neurobiol 2012;99:246-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Querin G, Bertolin C, Da Re E, et al. Non-neural phenotype of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: results from a large cohort of Italian patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:810-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wespes E. Metabolic syndrome and hypogonadism. Eur Urol Suppl 2013;12:2-6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu IC, Lin HY, Sparks JD, et al. Androgen receptor roles in insulin resistance and obesity in males: the linkage of androgen-deprivation therapy to metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2014;63:3180-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: WHO; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure, national heart and blood institute; national high blood pressure education program coordinating committee: seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985;28:412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American heart association/national heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fratta P, Nirmalananthan N, Masset L, et al. Correlation of clinical and molecular features in spinal bulbar muscular atrophy. Neurology 2014;82:2077-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashizume A, Katsuno M, Banno H, et al. Longitudinal changes of outcome measures in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Brain 2012;135(Pt 9):2838-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerstenmaier IF, Gibson RN. Ultrasound in chronic liver disease. Insights Imaging 2014;5:441-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaiani S, Avogaro A, Bombonato GC, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in nonobese patients with diabetes: prevalence and relationships with hemodynamic alterations detected with doppler sonography. J Ultrasound 2009;12:1-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mottillo S, Filio KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56:1113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakatsuji H, Araki A, Hashizume A, et al. Correlation of insulin resistance and motor function in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. J Neurol 2017;264:839-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodama K, Tojjar D, Yamada S, et al. Ethnic differences in the relationship between insulin sensitivity and insulin response. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1789-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weibrecht K, Dayno M, Darling C, et al. Liver aminotransferases are elevated with rhabdomyolysis in the absence of significant liver injury. J Med Toxicol 2010;6:294-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005;129:113-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomonaco R, Bril F, Portillo-Sanchez P, et al. Metabolic impact of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2016;39:632-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guber RD, Takyar V, Kokkinis A, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2017;89:2481-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome update. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2016;26:364-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allan CA, McLachlan RI. Androgens and obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2010;17:224-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith JC, Bennett S, Evans LM, et al. The effects of induced hypogonadism on arterial stiffness, body composition, and metabolic parameters in males with prostate cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:4261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C, Jackson G, Jones TH, et al. Low testosterone associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome contributes to sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular disease risk in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1669-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalinchenko SY, Tishova YA, Mskhalaya GJ, et al. Effects of testosterone supplementation on markers of the metabolic syndrome and inflammation in hypogonadal men with the metabolic syndrome: the double-blinded placebo-controlled Moscow study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73:602-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zitzmann M, Gromoll J, von Eckardstein A, et al. The CAG repeat polymorphism in the androgen receptor gene modulates body fat mass and serum concentrations of leptin and insulin in men. Diabetologia 2003;46:31-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Möhlig M, Arafat AM, Osterhoff MA, et al. Androgen receptor CAG repeat length polymorphism modifies the impact of testosterone on insulin sensitivity in men. Eur J Endocrinol 2011;164:1013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin HY, Xu Q, Yeh S, et al. Insulin and leptin resistance with hyperleptinemia in mice lacking androgen receptor. Diabetes 2005;54:1717-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HY, Yu IC, Wang RS, et al. Increased hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in mice lacking hepatic androgen receptor. Hepatology 2008;47:1924-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly DM, Nettleship JE, Akhtar S, et al. Testosterone suppresses the expression of regulatory enzymes of fatty acid synthesis and protects against hepatic steatosis in cholesterol-fed androgen deficient mice. Life Sci 2014;109:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McInnes KJ, Smiths LB, Hunger NI, et al. Deletion of the androgen receptor in adipose tissue in male mice elevates retinol binding protein 4 and reveals independent effects on visceral fat mass and on glucose omeostasis. Diabetes 2012;61:1072-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]