Abstract

Autosomal dominant LGMD1D has been described in multiple families in Asia, Europe, and USA. However, to the best of our knowledge, no cases of LGMD1D have been reported among native Bedouin Saudi families. Fifty Saudi families with LGMD were analyzed and the causative underlying genes were studied utilizing genome wide linkage, homozygosity mapping, and neurological gene panel. We identified one family of a Bedouin origin with LGMD1D. Two patients had progressive proximal and distal weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory symptoms. Creatinine kinase was normal. Muscle biopsy showed marked variation in myofibers size with scattered angular atrophic fiber, necrotic fibers, and myophagocytosis, with red-rimmed vacuoles depicting a sarcoplasmic body. Heterozygous c.C287T (p.P96L) variant in exon 5 of DNAJB6 (NM_005494) gene was found. This change is localized within glycine and phenylalanine rich domain and alter an amino acid residue. Our findings will expand on the existing genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of this disorder and aid in elucidating hidden mechanisms implicated in LGMD1D.

Key words: DNAJB6, LGMD1D, LGMD, Saudi Arabia, cytoplasmic inclusion, muscular dystrophy

Introduction

Limb girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMD) are not commonly encountered in clinical practice. Only scarce reports of LGMD originated from the Middle East or Arabic countries have been described in the literature (1, 2). LGMD has been classified to different subtypes based on the genetic mutations responsible for the disease, encompassing a genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous group of disorders. Autosomal dominant LGMD1D is relatively rare, accounting for only 5-10% of all LGMD cases (3). Recently, mutations in the DnaJ homolog, subfamily B, member 6 (DNAJB6) gene have been described in patients with LGMD1D (OMIM 603511) (4-15). Patients with LGMD1D typically present with progressive proximal muscle weakness manifesting as slow exercise pace and capacity in late teens. A few patients may have additional features of distal weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory weakness (8, 10, 12-15).

Autosomal dominant LGMD1D has been described in multiple families in Asia, Europe, and USA (4-15). However, to the best of our knowledge, no cases of LGMD1D have been reported among native Bedouin Saudi families. Utilization of next generation sequencing technology might lead to an accurate estimation of the true prevalence of this disease in Saudi Arabia by potentially classifying more cases of undiagnosed muscular dystrophies (2). Herein, we report the first identified native Saudi Bedouin family with LGMD1D due to heterozygous mutation in DNAJB6 gene (NM_005494:c.C287T;p.P96L).

Materials and methods

Patients inclusion

The Institutional Review Board granted approval of this study and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by Hospital Research Advisory Council and Ethical Committee. A cohort of 50 Saudi Arabian families with LGMD were enrolled for this study under an IRB-approved protocol (RAC# 2070005). All patients were examined at the Neuromuscular Clinic in the Department of Neurosciences, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSH&RC) over a period of 12 years and recruited for this study to identify the causative underlying genes utilizing a genome wide linkage, homozygosity mapping, and neurological gene panel. We performed a retrospective review of the electronic medical records and charts of this Arabian family and obtained patient demographic and clinical data from the medical records for the entire family. History was taken, and clinical examination was performed on the affected cases and their family members. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained for the affected patients.

Neurological gene panel sequencing & analysis

Ten nanograms of DNA sample was treated to obtain the Ion Proton AmpliSeq library. DNA amplification required two pools of primers to cover all 768 known OMIM genes associated with neurological disorders. The library was further used in a batch of 24 normalized to 100pM samples which were pooled in equal ratios for emulsion PCR (ePCR) on Ion OneTouch™ System followed by the enrichment process using the Ion OneTouch™ ES, both procedures following the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The template-positive Ion PI Ion Sphere particles were processed for sequencing on the Ion Proton instrument (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reads were mapped to UCSC hg19 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and variants identified using the Ion Torrent pipeline (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The resultant variant caller file (vcf) was filtered using the Saudi Human Genome Program pipeline (16). Causative variant was validated by Sanger sequencing and further vetted for familial segregation based upon autosomal dominant inheritance.

Results

Clinical data

The family reported in this paper is a native Bedouin Arab originated from Northern Province of Saudi Arabia. The parents were first cousins and the sibships consisted only of 1 male.

Case 1: The proband is a 25-year-old male with a history of exertional dyspnea and proximal muscle weakness was referred to our service for further investigation and management. The patient noted that he was a slow runner in his teens, which progressed to difficulty climbing stairs at the age 20. This was also associated with difficulty getting up from a sitting position with complete Gower maneuver at age 23. He also complained of dysphagia to both solids and liquids with frequent chocking episodes and a nasal speech character. His symptoms were slowly progressive initially; however, they progressed more rapidly during the past 2 years, mainly with worsening lower limb weakness and noticeable involvement of the distal upper limbs and atrophy of the hands and forearms. Currently the patient is ambulating without assistance and able to perform activities of daily living independently.

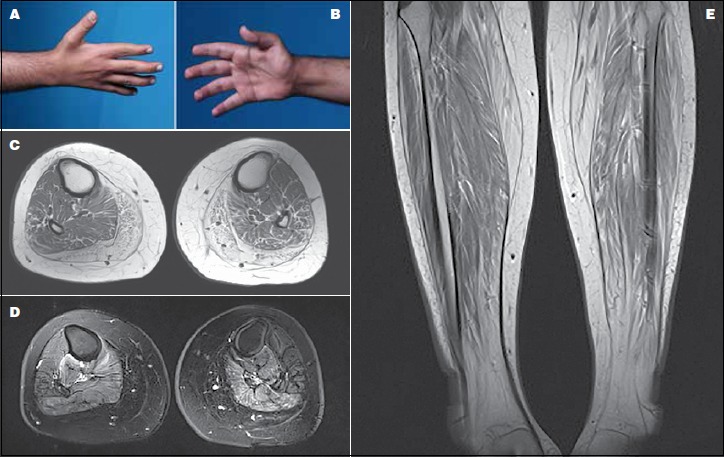

Hypernasality was noticed on examination. Upper limb examination demonstrated wasting of the small muscles of the hands (i.e. the dorsal interossei and the thenar and hypothenar muscles) (Figs. 1A-B). Motor examination revealed bilateral proximal muscle power of 4/5 and distal power of 3/5 in the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. No significant atrophy was present in the lower limbs. His lower limbs’ proximal power was 4/5 and distal power was 3/5. Notably, the patient had difficulty squatting. The patient was unable to walk on his heels or his toes; however, he was able to bear weight during these positions. The rest of his examination was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

(A-B) A photograph of the proband’s hand showing atrophy in the interossei (left) and thenar (right) muscle groups. (C) Axial T1-weighted MRI of the proximal leg showing selective involvement of the medial and posterior muscle groups with fatty infiltration. (D) Axial T2-weighted MRI of the mid-thigh depicting fiber changes in the posterior and medial muscle compartment. (E) Coronal STIR MRI of the proximal thighs demonstrating marked bilateral symmetrical increase signal intensity in the lateral compartment of the thigh consistent with fatty changes.

Creatinine kinase (CK) level was up to 195 IU and pulmonary function test was within normal limits. Electrophysiologic studies including nerve conduction study (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) showed clear myopathic features of motor units. T1-weighted MRI of the lower extremities depicted chronic atrophic changes in the gastrocnemius and peroneous muscles. T2-weighted images with fat saturation demonstrated symmetrical involvement of the posterior compartment (i.e. soleus, tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor Hallusis longus muscles) with high signal intensity. Right-sided tibialis anterior showed myoedema and was characteristically more involved than its left-sided counterpart (Figs. 1C-D-E).

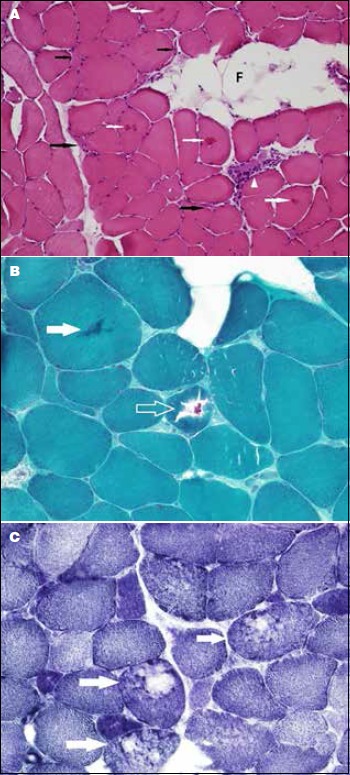

A muscle biopsy showed moderate to marked variation in myofiber size with scattered atrophic fibers having elongated and angular contours (Fig. 2A). There was also a rare necrotic fiber, mild endomysial (interstitial) fibrosis, and fatty infiltration. Scattered fibers with eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions and rimmed vacuoles were noted. These vacuoles stained negatively with acid phosphatase and congo red stains. The vacuoles were rimmed with the modified Gomori trichrome stain (Fig. 2B). The NADH-TR reaction revealed a disorganized intermyofibrillar network resulting in a “moth-eaten” appearance (Fig. 2C). Immunohistochemical staining for the slow and fast myosin heavy chains isoforms revealed predominance of slow (type 1) myofibers. No selective myofiber type atrophy was noted.

Figure 2.

(A) Cross-section of a freshly frozen skeletal muscle showing moderate to marked variation in myofiber size with scattered elongated and angular atrophic fibers (black arrows). A necrotic fiber with myophagocytosis (arrowhead) and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions (white arrows) are seen. Note the focal fatty infiltration (F). (B) Magnification of a trichrome-stained section depicting a cytoplasmic inclusions (solid arrow and open arrow). Note the atrophic fibers and the interstitial fibrosis. (C) A cryostat section stained with NADH-TR reaction showing several fibers (arrows) with disruption of the intermyofibrillar network giving a “moth-eaten” appearance.

Case 2: The proband’s father, a 58-year-old male who developed difficulty walking at age 18 with slow running pace and capacity. He noted that he walked on the medial aspect of his heels to support his weight; however, he had frequent falls, developed difficulty getting up from sitting position, and complete Gower at age 30. His symptoms progressed and needed a cane for ambulation at age 32 and became wheelchair bound at age 35. At the age 38, he had difficulty changing positions while seated, developed head drop, and later could not turn while in bed rendering him to sleep in a sitting position. At age 48, the patient developed recurrent chest infections and dysphagia to solids. He had a prolonged hospitalization course that ended up with respiratory failure, CO2 narcosis, and eventually a coma for 2 weeks. Subsequently, the patient underwent tracheostomy and was put on a ventilator due to respiratory weakness, as well as a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for feeding. Currently, the patient is bedbound and ventilator dependent with tube feeding. He can communicate via a speaking valve and has normal cognition.

Neurological examination showed normal cranial nerves except for a weak tongue and a gag reflex. There was a moderate degree of atrophy in the small muscles of the hand. Neck flexion power was 3/5 and 4/5 for neck dorsiflexion. His power was 1/5 in deltoids, 0/5 in biceps and triceps, 2/5 in wrist flexion, and 2/5 in wrist extension and finger flexion bilaterally. His ankle dorsiflexion power was 2/5 bilaterally. The remainder of his lower limb muscle power was 0/5. The patient also had scoliosis to the right side with winging of the scapulae. The power in the subscapularis and infrascapularis muscles was 1/5, and pectoralis muscle power was 2/5. Reflexes were depressed except for normal planter reflexes. The rest of his examination was unremarkable. CK level was normal, while NSC and EMG showed severe myopathic changes. His muscle and biopsy and MRI findings were similar to the proband.

Genetic analysis

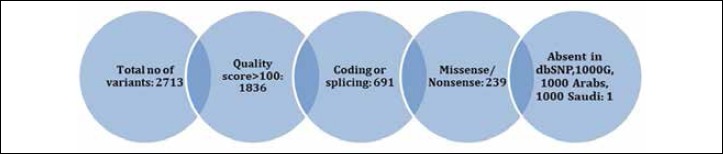

Neurological gene pane in the index case identified 2714 variants relative to the UCSC hg19 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) reference sequence. Variants were annotated using in-house programs that extend the public Annovar package with other commercial datasets such as HGMD, and in-house databases made up of a collection of disease-causing and polymorphic variants observed in individuals of Arab ethnicity. These were further filtered to exclude previously reported variants (present in dbSNP, 1000 genomes and 2000 Arab exomes), the list was narrowed to 59. Non-relevant variants were filtered out based on their quality, 5 variants survived. By only focusing on exonic and splice site variants we decreased the number to 1. (Fig. 3). It was a heterozygous variant in exon 5 of DNAJB6 (NM_005494:c.C287T;p.P96L). The gene has been associated with muscular dystrophy, limb-girdle, type 1D. This mutation localizes within glycine and phenylalanine rich domain and alter an amino acid residue. This heterozygous change was confirmed by Sanger sequencing, and the mutation segregated dominantly with disease in the family studied

Figure 3.

Filtration process of neurological gene panel results.

Discussion

There is an existing confusion in the LGMD1D nomenclature. The 7q36 locus has been designated as the site of gene defect for LGMD1E initially or LGMD1D/1E (5,17). However, according to the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee, the current nomenclature for LGMD associated with DNAJB6 mutations is LGMD1D. The first identification of a pathogenic locus on chromosome 7 linked to LGMD1 was in 1995 by Speer et al. (18) in 2 American families. The disease was further described in a Finnish family where it was further localized to a possible genetic mutation on the same locus (4). Subsequently, Harms et al. (5) identified mutations within the G/F domain of the DNAJB6 gene, of the LGMD1 locus on chromosome 7q36, thereby classifying DNAJB6 dystrophy as a novel cause of autosomal dominant inherited myopathy (1-3, 5, 6).

Further studies described American, Canadian, Italian, French, Finnish, Japanese, and Taiwanese families with LGMD1D have also identified the causative gene to be DNAJB6 (4-15). Missense mutations and deletions have been identified in this gene, including p.Phe89Ile, p.Phe93Leu, p.Asn95Ile, p.Phe96Arg, p.Phe96Ile, p.Phe96Leu, and p.Asp98del (4-15). It appears that the loss of phenylalanine form the protein domain is more important in the pathophysiology of the disease than the type of amino acid substitution (6). Given that most of the reported mutations occur in or in a close proximity to the p.Phe93Leu region, this suggests that this area could be a mutational hot spot within the DNAJB6 gene (6, 7, 10). Both of our patients harbored a P96L mutation in the DNAJ6B gene with additional phenotypic features expanding the previously described phenotypes. This P96L mutation has been previously described in a Taiwanese family (14). Tentative genotype-phenotype correlation indicate that p.Phe91 mutations in G/F domain are associated with a severe disease, while p.Phe89, p.Pro96, and p.Phe100 mutations were linked to an intermediate severity. Interestingly, p.Phe93 mutations were associated with the least severe phenotype (6, 10, 12, 13).

The DNAJB6 protein (encoded by the DNAJB6 gene) is a member of the heat shock protein family (heat shock protein 40) a class of co-chaperones that is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, with a higher expression rate in the brain than other tissues (19). The protein has a multitude of functions including suppressing protein aggregation and toxicity of polyglutamine proteins (19-21). The DNAJB6 protein has three domains: an N-terminal J domain, a variable C-terminal domain, and a G/F domain (13, 22). All the described LGMD1D mutations lead to amino acid substitutions or deletion in the G/F domain (4-15). The DNAJB6 protein has two isoforms a and b, which are produced by alternative splicing of its mRNA. DNAJB6a is located in the nucleus, while DNAJB6b is located in the cytosol (13, 22). Mutations in the isoform b are responsible for LGMD1D.

The mechanism by which mutant DNAJB6b causes muscular dystrophy is complex and not fully understood. In vitro studies suggest defective anti-aggregation properties by mutant DNAJB6b leading to toxic protein accumulation, interaction with the CASA complex, and BAG3 co-chaperones, which collectively cause altered protein degradation system and defective protein quality control (6, 19-21, 23). Pathologically, LGMD1D is characterized by the presence of rimmed vacuoles, cytoplasmic inclusions, and disintegrated myofibrils as shown in Figure 2 (5, 12). EMG and NC neurophysiological studies generally show myopathic changes and CK levels are typically normal or moderately elevated (4-15). All of these findings were also observed in our patients.

The MRI findings of LGMD1D have been studied by Sandell et al. (24) The authors found a typical pattern of involvement, showing fatty degeneration of multiple muscles across the course of the disease. The MRI findings in our patients were also similar to what Sandell et al. (24) observed in their cohort along with chronic atrophic changes in the gastrocnemius and peroneous muscles.

As the number of reports continues to increase, there has been phenotypic expansion in LGMD1D clinical presentation. The age of onset varies from teenage to middle age years, with the youngest reported case in a 14-year-old (11). The initial symptoms are those related to proximal myopathy, involving predominantly the lower extremities presenting as difficulty running, climbing stairs, or rising up from a sitting position. Some patients have a concurrent distal muscle weakness and may present with muscle atrophy either proximally or distally (4-15). Other uncommonly encountered symptoms include dysphagia, dysarthria, myalgia, conduction defects in the heart, and respiratory symptoms (8, 10, 12-15). Interestingly, both of our patients had distal muscle weakness, dysphagia, and respiratory symptoms.

The natural history of LGMD1D is variable. The majority of patients have a slowly progressive disease and remain ambulatory till their early 50’s. However, a relentlessly aggressive form may occur, particularly among patients with a young onset (6, 11-13). Unfortunately, one of our patients was rendered wheelchair bound in his 30’s. Our two cases lie within the phenotypic spectrum of previously reported LGMD1D phenotypes. Additionally, our native Saudi Bedouin patients harbored a mutation c.C287T (p.P96L) in the DNAJB6 gene. Exome-sequencing technology had aided us to discover this LGMD1D family among 50 other LGMD Saudi families (16). Utilization of this technology may further help us unleash more families with LGMD1D and provide a more accurate estimate of the true prevalence of this rare entity by classifying more cases of undiagnosed muscular dystrophies. Our study will therefore expand on the existing genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of this disorder and aid in elucidating hidden mechanisms implicated in LGMD1D.

References

- 1.Boyden SE, Salih MA, Duncan AR, et al. Efficient identification of novel mutations in patients with limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Neurogenetics 2010;11:449-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monies D, Alhindi HN, Almuhaizea MA, et al. A first-line diagnostic assay for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy and other myopathies. Hum Genomics 2016;10:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straub V, Murphy A. Udd B. 229th ENMC international workshop: Limb girdle muscular dystrophies – Nomenclature and reformed classification Naarden, the Netherlands, 17-19 March 2017. Neuromuscul Disord 2018;28:702-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackman P, Sandell S, Sarparanta J, et al. Four new Finnish families with LGMD1D; refinement of the clinical phenotype and the linked 7q36 locus. Neuromuscul Disord 2011;21:338-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harms MB, Sommerville RB, Allred P, et al. Exome sequencing reveals DNAJB6 mutations in dominantly-inherited myopathy. Ann Neurol 2012;71:407-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarparanta J, Jonson PH, Golzio C, et al. Mutations affecting the cytoplasmic functions of the co-chaperone DNAJB6 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet 2012;44:450-5, S1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato T, Hayashi YK, Oya Y, et al. DNAJB6 myopathy in an Asian cohort and cytoplasmic/nuclear inclusions. Neuromuscul Disord 2013;23:269-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couthouis J, Raphael AR, Siskind C, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a DNAJB6 mutation in a family with dominantly-inherited limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:431-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam TS, Li W, Heo SH, et al. A novel mutation in DNAJB6, p.(Phe91Leu), in childhood-onset LGMD1D with a severe phenotype. Neuromuscul Disord 2015;25:843-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggieri A, Brancati F, Zanotti S, et al. Complete loss of the DNAJB6 G/F domain and novel missense mutations cause distal-onset DNAJB6 myopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2015;3:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmio J, Jonson PH, Evilä A, et al. Novel mutations in DNAJB6 gene cause a very severe early-onset limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 1D disease. Neuromuscul Disord 2015;25:835-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandell S, Huovinen S, Palmio J, et al. Diagnostically important muscle pathology in DNAJB6 mutated LGMD1D. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2016;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruggieri A, Saredi S, Zanotti S, et al. DNAJB6 myopathies: focused review on an Emerging and Expanding Group of Myopathies. Front Mol Biosci 2016;3:63 eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai PC, Tsai YS, Soong BW, et al. A novel DNAJB6 mutation causes dominantly inherited distal-onset myopathy and compromises DNAJB6 function. Clin Genet 2017;92:150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonson PH, Palmio J, Johari M, et al. Novel mutations in DNAJB6 cause LGMD1D and distal myopathy in French families. Eur J Neurol 2018;25:790-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monies D, Abouelhoda M, AlSayed M, et al. The landscape of genetic diseases in Saudi Arabia based on the first 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes. Hum Genet 2017;136:921-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandell S, Huovinen S, Sarparanta J, et al. The enigma of 7q36 linked autosomal dominant limb girdle muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speer MC, Gilchrist JM, Chutkow JG, et al. Evidence for locus heterogeneity in autosomal dominant limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 1995;57:1371-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hishiya A, Salman MN, Carra S, et al. BAG3 directly interacts with mutated alphaB-crystallin to suppress its aggregation and toxicity. PLoS One 2011;6:e16828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arai H, Atomi Y. Chaperone activity of alpha B-crystallin suppresses tubulin aggregation through complex formation. Cell Struct Funct 1997;22:539-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arndt V, Dick N, Tawo R, et al. Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy is essential for muscle maintenance. Curr Biol 2010;20:143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan CY, Lee S, Cyr DM. Mechanisms for regulation of Hsp70 function by Hsp40. Cell Stress Chaperones 2003;8:309-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding Y, Long PA, Bos JM, et al. A modifier screen identifies DNAJB6 as a cardiomyopathy susceptibility gene. JCI Insight 2017;2pii: 94086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandell SM, Mahjneh I, Palmio J, et al. Udd BA. ‘Pathognomonic’ muscle imaging findings in DNAJB6 mutated LGMD1D. Eur J Neurol 2013;20:1553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]