Abstract

Background

Fatigue is a common, distressing, and persistent symptom for patients with malignant tumor including colorectal cancer (CRC). Although studies of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) have sprung out in recent years, the pathophysiological mechanisms that induce CRF remain unclear, and effective therapeutic interventions have yet to be established.

Methods

To investigate the effect of the traditional Chinese medicine YangZheng XiaoJi (YZXJ) on CRF, we constructed orthotopic colon cancer mice, randomly divided into YZXJ group and control (NS) group. Physical or mental fatigue was respectively assessed by swimming exhaustion time or suspension tail resting time. At the end of the experiment, serum was collected to measure the expression level of inflammatory factors by ELISA and feces to microbiota changes by 16s rDNA, and hepatic glycogen content was detected via the anthrone method.

Result

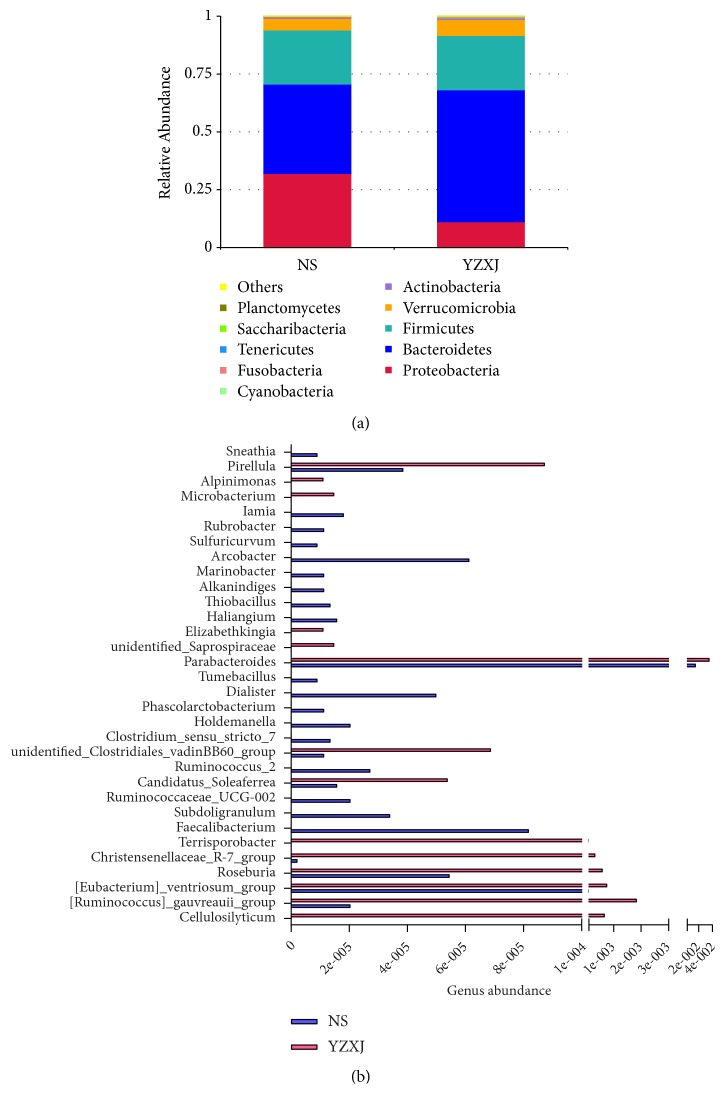

The nutritional status of the YZXJ group was better than that of the control group, and there was no statistical difference in tumor weight. The swimming exhaustion times of YZXJ group and control group were (162.80 ± 14.67) s and (117.60 ± 13.42, P < 0.05) s, respectively; the suspension tail resting time of YZXJ group was shorter than that of the control group (49.85 ± 4.56) s and (68.83 ± 7.26) s, P < 0.05)). Serum levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in YZXJ group were significantly lower than the control group (P < 0.05). Liver glycogen in YZXJ group was (5.18 ± 3.11) mg/g liver tissue, which was significantly higher than that in control group (2.95 ± 2.06) mg/g liver tissue (P < 0.05). At phylum level, increased abundance of Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria and decreased Proteobacteria in YZXJ group emerged as the top differences between the two groups, and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was decreased in YZXJ group compared to the control group. At genus level, the abundance of Parabacteroides, unidentified Saprospiraceae, and Elizabethkingia which all belong to phylum Bacteroidetes were increased, while Arcobacter, Marinobacter, Alkanindiges, Sulfuricurvum, Haliangium, and Thiobacillus in phylum Proteobacteria were decreased after YZXJ intervention. YZXJ can also increase Pirellula, Microbacterium, and Alpinimonas and decrease Rubrobacter and Iamia.

Conclusion

YZXJ may reduce the physical and mental fatigue caused by colorectal cancer by inhibiting inflammatory reaction, promoting hepatic glycogen synthesis, and changing the composition of intestinal microbiota.

1. Introduction

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the common, suffering and persistent symptoms of cancer patients, often accompanied by the entire course of malignancy. The prevalence of CRF may vary with an estimate of 60%–96% in malignant tumor patients who are undergoing treatment and experiencing fatigue [1, 2]. Unlike the transient fatigue of normal healthy people, the incidence of CRF is sudden, with the subjective sense of tiredness or exhaustion which is not proportional to recent physical activity and interferes with usual functioning; rest or sleep cannot alleviate it [3]. Due to the diversity of clinical manifestations of malignant tumors, CRF often appears as part of a symptom cluster (including cachexia and neuropsychological disorders) [4]. CRF, including physical and mental fatigue, directly or indirectly affects the physical and mental state of cancer patients, reducing quality of life and compliance with treatment, which is an important issue that cannot be ignored in the treatment of cancer.

Although the exact mechanisms have not yet been clearly elucidated, what can be confirmed is that multiple factors interact to cause the incidence of CRF, both central and peripheral factors. The former includes cytokine dysregulation, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis disruption, circadian rhythm, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), vagal afferent nerve function, while peripheral factors mainly refer to energy metabolism abnormalities, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) deficiency and muscle acidosis [5–7]. In colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, the severity of CRF is closely related to nutrition status, especially white blood cells and serum calcium levels [8]. A growing body of evidence suggests that the tumor itself, the patient's mental stress, or chemoradiotherapy mediates a low-grade inflammatory response that is inextricably linked to the development of CRF. Recent studies also indicate that interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type II (sTNF type II), and C-reactive protein (CRP) have played a significant contribution [9]. These inflammatory factors can both act directly on the central nervous system and affect the HPA axis [10, 11]. Some scholars also have found that elevated levels of IL-1β in peripheral blood activate the vagus nerve, which in turn leads to fatigue [12].

Metabolic abnormalities play an important role in peripheral causal factors, including immune dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation, and skeletal muscle cell acidosis, which may cause different degrees of insufficient energy synthesis [13, 14]. Hepatic glycogen is a form of energy storage in the body. During vigorous exercise or pathological conditions, energy consumption increases, and hepatic glycogen is decomposed into glucose, which provides energy for muscles and helps to maintain endurance. Data showed that liver glycogen in fatigue patients was generally reduced, while appropriate supplementation could alleviate fatigue [15]. Chronic inflammation, as well as chemoradiotherapy and many other factors, can cause metabolic abnormalities. For example, chronic inflammation induces insulin resistance, as a consequence of a decrease in carbohydrate synthesis glycogen and also increases energy expenditure by about 10% [16, 17]. Yet it is true that mitochondria are usually inevitably damaged in routine clinical practice, which also causes insufficient energy supply [18].

In recent years, the relationship between intestinal microbiota imbalance and host health has attracted more attention, including fatigue syndrome, suggesting that the brain-gut axis may play an important role in the occurrence of mental fatigue. Researchers have found that in the intestines of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), the abundances of Alistipes, Lactonifactor, Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Prevotella spp., etc., are increased; however, some probiotics such as Bifidobacteria are reduced [19, 20]. It is particularly noteworthy that intestinal microecological disorders are closely related to the occurrence and development of CRC. Due to the special positional relationship, the intestinal microbiota is actually an important part of the CRC microenvironment. Therefore, CRF in patients with CRC may have a special mechanism different from that of other solid tumors; that is, in addition to inflammatory reactions and metabolic abnormalities, there may exist such mechanism as intestinal microbiota imbalance. Increased abundances of Streptococcus gallolyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacteroides fragilis, Prevotella, Helicobacter, and Fusobacterium nucleatum and decreased probiotics like Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are detected in CRC patients by previous reporting [21, 22]. Likewise, fatigue is considered to have an association with increased bacterial growth as Enterococcus and Prevotella or decreased abundance of probiotics [23, 24].

Such a complex pathogenesis of CRF means that the treatment cannot be unique or single. Although guidelines have been issued, lots of clinical obstacles need to be overcome. Current treatment strategies for CRF include nondrug and drug therapy. Nondrug therapies contain physical exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychosocial intervention [25]. The study suggested that aerobic combination exercise was the first recommendation rather than simple resistance training; moreover, light to moderate physical activity is beneficial, and otherwise strenuous activities can be counterproductive [26]. For drug therapy, a meta-analysis showed that there is no specific drug for the treatment of CRF, and some studies have shown a preference for modafinil and methylphenidate. As for Erythropoietin, Dexamethasone, acetylsalicylic acid, methylprednisolone, armodafinil, amantadine, and L-carnitine, the efficacy remains to be further observed. Meanwhile, toxic side effects of these preparations also limit the widespread and long-term clinical use [27, 28].

Thus, seeking an integrative treatment program is the future direction [29]. Chinese traditional medicine has its unique advantages in this respect. For example, except for the well-known Ginseng, some Chinese herbal formulas also have good antifatigue effects [30–33]. Acupuncture is considered a beneficial alternative treatment to CRF in patients with breast cancer or undergoing anticancer therapy [34]. However, it should be noticed that most of these methods do not treat tumors, and even some of them may be contraindicated. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a new prescription to treat CRF. YangZheng XiaoJi (YZXJ) is recently developed, consisting of 16 traditional Chinese medicines named Astragalus membranaceus, Fructus ligustri lucidi, Ginseng, Rhizoma curcumae, Ganoderma, Gynostemma pentaphyllum, Atractylodes macrocephala, Scutellaria barbata, Hedyotis diffusa, Poria cocos, Eupolyphaga seu steleophaga, Endothelium corneum gigeriae galli, Mock strawberry herb, Bittersweet herb, Herba artemisiae scopariae, and Cynanchum paniculatum. Chromatographic analysis showed that the main components were oleanolic acid and ursolic acid. Jiang et al. found that YZXJ inhibits tumor growth by antagonizing HGF/c-Met and inhibiting angiogenesis [35, 36]. At present, a large randomized controlled clinical trial of YZXJ for CRF was conducted in several Chinese hospitals (Registration number: NCT02195453). The primary end point of the trial was the effect of YZXJ on the fatigue of patients with advanced lung cancer, which results will be announced soon and are worth looking forward to. The mechanism of YZXJ anti-CRF also needs to be clarified.

In this study, we established the orthotopic implantation model of CT26 cells in Balb/c mouse to explore the efficacy of YZXJ in the treatment of CRF caused by CRC, and the related mechanism, aiming to provide experimental basis for finding a new method for treating CRF in patients with CRC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cancer Cell Line

CT26 cell line used for these experiments was purchased from the Shanghai Cell Collection Committee, maintained in tissue culture flasks (5% CO2, air at 37°C) containing RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) with 10% newborn calf serum (Invitrogen). Trypsinization and inheritance were carried out with EDTA/pancreatin mixture (Gibco). When reaching the logarithmic growth phase, CT26 cells were prepared as single cell suspension at a concentration of 2×107/ml.

2.2. Orthotopic Mouse Model

Forty-two SPF raised 6- to 7-week-old BALB/c mice (male) were obtained from the Animal Center of Hebei Medical University, weighing about 18~22 g, raised in the SPF-level laboratory of the Animal Experimental Center of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, room temperature 25°C ± 1°C. All operations were carried out according to the Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University.

After a 7d acclimatization period, tumors were started by injecting CT26 cell suspension at a dose of 0.1ml/mouse to the right flank of two mice. Two weeks later, the subcutaneous tumors which grown to a diameter of about 1 cm were isolated and cut into 2 mm × 2 mm × 1 mm size and reserved in normal saline. The other mice were also anesthetized with 3% pentobarbital sodium 40~45 mg/kg, routinely disinfected the skin then opened the abdominal cavity, gently scraped off the serosal surface on the opposite side of mesentery at the colon of about 1cm from the ileocecal junction. The prepared fresh tumor mass was placed in the formed “diverticulum” with squeezing a medical drop to seal the tumor nest and close the abdomen after returning cecum.

2.3. Experimental Design

Mice were randomized to experimental (YZXJ) group and control (NS) group (n = 40). On the 2nd day after building model, the experimental group was administered with YZXJ suspension (Yiling pharmaceutical, Shijiazhuang, China) at a dose of 1.6 g/kg/d for 21 days, and the control group was given a corresponding volume of normal saline. Mice were sacrificed under anesthesia with removing and weighing the abdominal colorectal tumors on the 21st day.

2.3.1. Observation of the Fatigue State

(1) Recording the General Condition. Changes in hair appearance, mental state, activity, food intake (weighed every 4d), and body weight (every 1w) of the mice in each group were observed and recorded.

(2) Determination of Physical Fatigue. Physical exhaustion was used to assess somatic fatigue. Three days before modeling, all mice were placed in a swimming box (water temperature 25°C ± 1°C) for adaptive training, 5 min/d. On the 10th day after administration, exhaustive swimming time was recorded by dropping 7% body weight of lead on the tail, which standard is the nose tip sinking into the water for 6 s.

(3) Determination of Mental Fatigue. On the 14th day, we fixed the tail on a tail suspension tester with a tape in a dark room and kept mouse head 5 cm away from the bottom of tester. After 2 min of adaptive suspension, the mice resting times were recorded in the last 4 min.

2.3.2. Detection of Inflammatory Factors in Serum

Blood samples were taken from eyeball at the end of the experiment. After standing for 30 min, it was centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 10 min, and the supernatant was stored in a -80°C refrigerator until further analysis for detecting cytokine levels of plasma IL-1α/β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ according to ELISA kit (MultiSciences).

2.3.3. Comparison of Hepatic Glycogen

The liver tissue was weighed 100 mg, boiling with 300 μl concentrated alkaline for 20 min to destroy other components except liver glycogen. Then, we mixed 1% hepatic glycogen detection solution prepared by double distilled water and 2 ml anthrone developer dissolved in 95% concentrated sulfuric acid (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) and continued boiling for 5 min; the absorbance of each measuring tube and standard glycogen detection solution (0.001 mg) was measured at a wavelength of 620 nm after natural cooling, and zero was adjusted with a blank tube. The content of hepatic glycogen was calculated by the following formula.

| (1) |

2.3.4. Determination of Intestinal Microbiota

After administering for 21 days, the feces (about 1 g/mouse) were collected using a sterile eppendorf tube and frozen at -80°C. The effect of YZXJ on the intestinal microbiota of orthotopic colon cancer mice was detected by 16S rDNA; a small fragment library was constructed for single-end sequencing based on the IonS5TM XL platform, which revels the species composition of samples through the cut filtering of reads, OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Units) clustering, species annotation and abundance analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Data were expressed as mean ± SD analyzed by t test, and those who did not meet the positive distribution were tested by rank sum test. All the Clean Reads of samples were clustered by Uparse software, and the sequence was clustered into OTUs with 97% identity. Meanwhile, the sequence with the highest frequency in OTUs was used as the representative sequence. Through specimen annotation of OTUs representative sequences using the Mothur method and SSUrRNA database (set threshold value as 0.8~1), taxonomic information can be obtained to calculate out community composition of each sample in kingdom, phylum, and class, order, family, genus, respectively. Fast multisequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE software (Version 3.8.31) to obtain a systematic relationship of all OTUs representative sequences. The Qiime software (Version 1.9.1) was used to calculate the Chao1, Simpson index and Unifrac distance, and the R software (Version 2.15.3) was used to analyze the difference between α and β diversity index groups. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 21.0). All results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

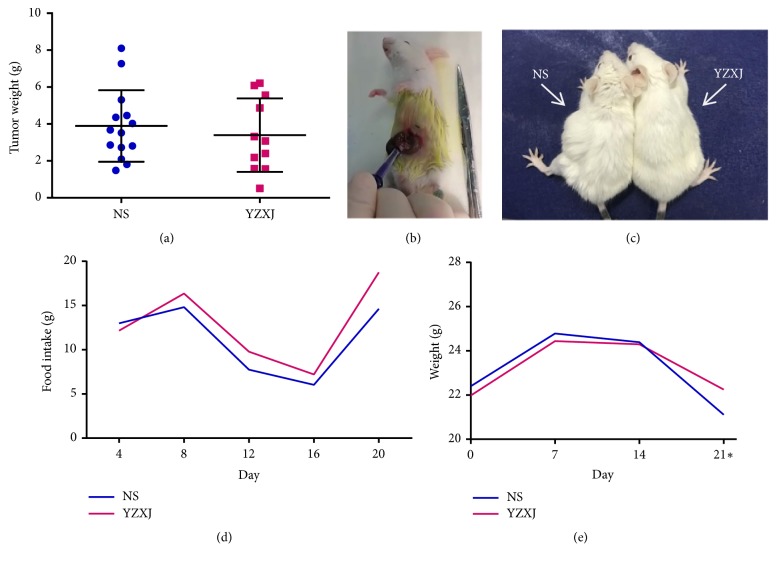

Totally 40 mice underwent surgical operation. Finally, 14 of NS group and 11 of YZXJ group were successfully modeled. In the end, the orthotopic tumor mass of NS group was (3.90 ± 0.52) g, and YZXJ group was (3.40 ± 0.60) g, which was not statistically significant (t = 0.63, P = 0.53, Figures 1(a) and 1(b)).

Figure 1.

General condition of the two groups. (a) Tumor weight comparison of NS and YZXJ groups. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups. (b) Colon cancer orthotopic transplantation in BALB/c mice. (c) Appearance and activity. NS group had rougher, lusterless hair, more apathetic condition, and lower movement than YZXJ group. (d) Average daily food intake of each mouse weighted every 4 days. (e) Average weight of each mouse weighted every week. ∗ Weight without in situ tumor.

3.1. Impact on the General Condition

3.1.1. Appearance

Before administration, there were no differences between the two groups in mental state and activity. During experiment, mice in both groups gradually showed different degrees of poor gloss in hair, slowness of movement, and reduced food intake. Until the end of observation, mice in NS group had rougher hair and less lusters than YZXJ group, as well as apathetic and slow action, while mice in YZXJ group appeared more flexible (Figure 1(c)).

3.1.2. Food Intake

The average food intake of mice was evaluated every 4 days. As depicted in Figure 1(d), YZXJ group had more food intake than NS group and also presented an increasing food intake with the prolonged administration time, but the difference did not show statistical significance.

3.1.3. Body Weight

Body weight was measured every week, and tumor weight was subtracted from it in the last time. Although the difference in body weight between the two groups did not reach statistical significance, by the end of experiment, the weight loss trend of YZXJ group was slower than that of NS group (Figure 1(e)).

3.2. Impact on Fatigue

3.2.1. Physical Fatigue

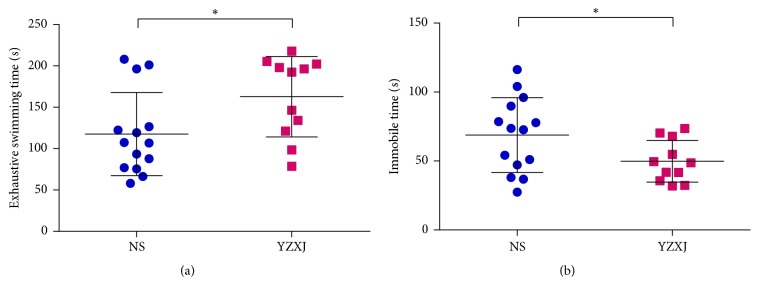

Exhaustive swimming time is shown in Figure 2(a). The swimming time of each mouse was close before modeling, but on the 10th day after intervention, exhaustive swimming time of YZXJ group was (162.80 ± 14.67) s, longer than that of NS group (117.60 ± 13.42) s, (t = 2.27, P = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Comparison of fatigue state. (a) Physical fatigue exhaustive swimming time of NS and YZXJ group tested after 10-day intervention. (b) Immobile time in tail suspension test of NS and YZXJ group tested after 14-day intervention. ∗ P<0.05.

3.2.2. Mental Fatigue

Figure 2(b) is the result of suspension tail experiment. It can be seen that the tail suspension resting time in YZXJ group was shorter than that in NS group [(49.85 ± 4.56) s vs. (68.83 ± 7.26) s, t = 2.22, P = 0.04]. This suggested that the energy and mental state of mice with orthotopic colon cancer were better in those taking YZXJ.

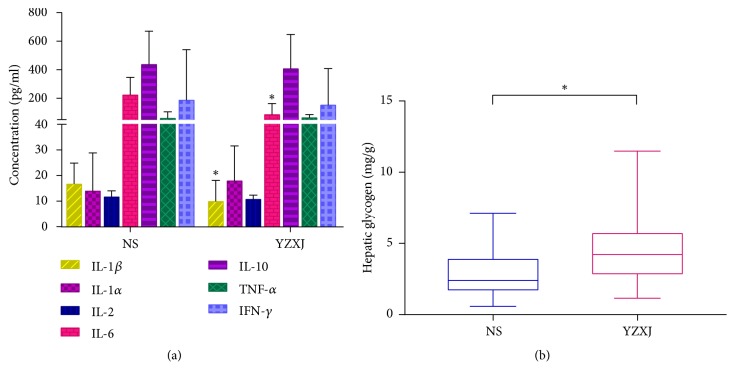

3.3. Impact on Serum Inflammatory Factors

To determine the possible factors of improving the fatigue performance, inflammatory factors levels associated with fatigue which once have been reported were tested in mice serum, including IL-1α/β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, IFN-γ. In expectation, fatigue-related inflammatory factors in YZXJ group were generally lower than NS group, particularly IL-1β and IL-6. The level of IL-1β in YZXJ group was significantly lower than NS group [(10.29 ± 7.86) pg/ml vs. (17.07 ± 7.84) pg/ml, P = 0.04]. The IL-6 level in YZXJ group was (92.40 ± 71.43) pg/ml, and NS group was (229.44 ± 117.54) pg/ml (P = 0.002) (Figure 3(a), Table 1).

Figure 3.

Concentration of inflammatory factors and hepatic glycogen. (a) Fatigue-related inflammatory factors in YZXJ group were generally lower than NS group, particularly for IL-1β and IL-6. (b) The level of liver glycogen in the two groups, reflexing the advantage energy reserve capacity in YZXJ treated mice. ∗ P<0.05.

Table 1.

Concentration of IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and INF-γ in NS and YZXJ groups. ∗P<0.05.

| Immune factors | NS | YZXJ | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β∗ | 17.07±7.84 | 10.29±7.86 | 2.15 | 0.04 |

| IL-1α | 14.34±14.55 | 18.32±13.33 | 0.70 | 0.49 |

| IL-2 | 12.01±2.07 | 11.08±1.33 | 1.29 | 0.21 |

| IL-6∗ | 229.44±117.54 | 92.40±71.43 | 3.40 | 0.002 |

| IL-10 | 443.61±227.34 | 413.29±234.43 | 0.33 | 0.75 |

| TNF-α | 65.56±40.45 | 69.84±17.07 | 0.33 | 0.75 |

| INF-γ | 193.16±348.26 | 158.33±250.25 | 0.28 | 0.78 |

3.4. Determination of Hepatic Glycogen

To investigate the effect of YZXJ on hepatic glucose metabolism, we detected liver glycogen. The results showed that the level of hepatic glycogen in NS group was (2.95 ± 2.06) mg/g, which increased to (5.18 ± 3.11) mg/g in YZXJ group (P = 0.04, Figure 3(b)), indicating YZXJ treatment was advantageous to promote reserve capacity of tumor-bearing mice.

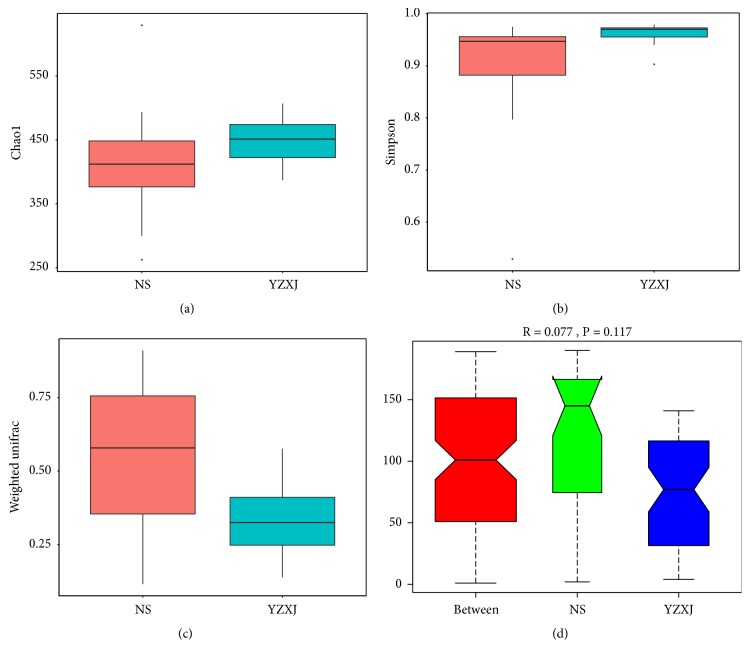

3.5. Changes in Intestinal Microbiota

To explore the influence of YZXJ on intestinal microbiota, 16s rDNA was used to detect the changes of intestinal microbiota in mice. The result displayed that comparison of α diversity including Chao 1 and Simpson index of YZXJ group were higher than NS group, which represent the bacteria abundance and diversity, respectively (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). However comparison in β diversity indicated that microbial community composition of YZXJ group was lower than NS group. ANOSIM analysis showed that the community structure difference between groups was greater than that within the group, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.117, Figures 4(c) and 4(d)).

Figure 4.

Comparison of α and β diversity. (a, b) Two indicators of α diversity detected in NS and YZXJ group. Chao 1 is represented as the bacteria abundance, and Simpson index reflects the bacteria diversity. (c) Unifrac distance of β diversity is used to calculate the distance between samples by using the evolutionary information and further constructing weighted Unifrac distance through OTUs abundance information. (d) Intergroups difference was greater than intragroup difference, but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.117).

In order to study the species with significant differences between groups, MetaStat method was used to test the species abundance at different levels. Results showed that at phylum level, increased abundance of Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria and decreased Proteobacteria in YZXJ group emerged as the top differences between two groups (Figure 5(a)). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios were 0.61 and 0.41 in NS and YZXJ group, respectively. At genus level, the abundance of Parabacteroides, unidentified Saprospiraceae, and Elizabethkingia which all belong to phylum Bacteroidetes were increased, while Arcobacter, Marinobacter, Alkanindiges, Sulfuricurvum, Haliangium, Thiobacillus in phylum Proteobacteria were decreased after YZXJ intervention, which also increased Pirellula, Microbacterium, and Alpinimonas and decreased Rubrobacter and Iamia (Figure 5(b), Table 2).

Figure 5.

Alteration of fecal microbiota due to the intervention of YZXJ. (a) Cumulative column chart of relative species abundance in phylum level. (b) Top differences of fecal microbiota shifts in genus level.

Table 2.

Differential fecal microbiota on genus level between NS and YZXJ groups.

| Differential cecal microbiota | Mean | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NS | YZXJ | ||

| Increased in the YZXJ group | |||

| Cellulosilyticum | 0 | 6.83 E-04 | 0.000999 |

| [Ruminococcus]_gauvreauii_group | 2.05E-05 | 1.85 E-03 | 0.008991 |

| [Eubacterium]_ventriosum_group | 1.05 E-04 | 7.68 E-04 | 0.02997 |

| Roseburia | 5.46E-05 | 6.03 E-04 | 0.032967 |

| Christensenellaceae_R-7_group | 2.27E-06 | 3.35 E-04 | 0.045954 |

| Terrisporobacter | 0 | 1.06 E-04 | 0.012987 |

| Candidatus_Soleaferrea | 1.59E-05 | 5.40E-05 | 0.013986 |

| unidentified_Clostridiales_vadinBB60_group | 1.14E-05 | 6.88E-05 | 0.02997 |

| Parabacteroides | 1.58 E-02 | 3.58 E-02 | 0.038961 |

| unidentified_Saprospiraceae | 0 | 1.49E-05 | 0.010055 |

| Elizabethkingia | 0 | 1.12E-05 | 0.035984 |

| Microbacterium | 0 | 1.49E-05 | 0.010055 |

| Alpinimonas | 0 | 1.12E-05 | 0.035984 |

| Pirellula | 3.87E-05 | 8.74E-05 | 0.030969 |

|

| |||

| Decreased in the YZXJ group | |||

| Faecalibacterium | 8.19E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Subdoligranulum | 3.41E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Ruminococcaceae_UCG-002 | 2.05E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Ruminococcus_2 | 2.73E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Clostridium_sensu_stricto_7 | 1.36E-05 | 0 | 0.008304 |

| Holdemanella | 2.05E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Phascolarctobacterium | 1.14E-05 | 0 | 0.018453 |

| Dialister | 5.00E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Tumebacillus | 9.10E-06 | 0 | 0.041006 |

| Haliangium | 1.59E-05 | 0 | 0.003737 |

| Thiobacillus | 1.36E-05 | 0 | 0.008304 |

| Alkanindiges | 1.14E-05 | 0 | 0.018453 |

| Marinobacter | 1.14E-05 | 0 | 0.018453 |

| Arcobacter | 6.14E-05 | 0 | 0.000999 |

| Sulfuricurvum | 9.10E-06 | 0 | 0.041006 |

| Rubrobacter | 1.14E-05 | 0 | 0.018453 |

| Iamia | 1.82E-05 | 0 | 0.001681 |

| Sneathia | 9.10E-06 | 0 | 0.041006 |

4. Discussion

CRF, a serious concomitant symptom of most cancer patients, is one of the problems that plague clinicians for its indefinite therapeutic strategy due to the ambiguous pathogenesis. In this study, we found that the traditional Chinese medicine prescription of YZXJ can significantly alleviate physical and mental fatigue of mice with orthotopic colon cancer and not promote tumor growth. Further studies revealed that YZXJ can reduce the serum inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-6, increase hepatic glycogen content, affect the composition of intestinal microbiota, mainly increase the abundance of Bacteroides, and also decrease the abundance of Proteobacteria and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. This study aimed to provide a basis for clinical search for a new method of CRF treatment and partially elucidate the mechanism of Chinese medicine in treating CRF.

At present, the most accepted view on the pathogenesis of CRF is inflammatory response. We found that YZXJ can reduce various inflammatory factors in mice blood, with the most significant decrease in IL-1β and IL-6. It is well known that tumor cells or mesenchymal cells in surrounding microenvironment can release a variety of inflammatory factors, so will the conventional anticancer treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Such chronic inflammation can induce fatigue syndrome through the following mechanisms: (1) triggering metabolic disorders, as a result of insufficient energy supply to cells; (2) increasing energy consumption of immune system, resulting in impaired immune function; and (3) causing neuroendocrine dysfunction, neurotransmitter metabolism disorder, or abnormal neuronal formation [37, 38]. Studies have shown that anti-inflammatory treatment can relieve fatigue; for example, selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors exhibit the most beneficial effects in restraining the inflammation markers in patients with depression [39]. Certain anti-inflammatory preparations can also attenuate fatigue symptoms [40, 41]. However, in the process of theoretical research towards clinical application, there still exist many problems waiting to be solved, such as safety, and there are no commercially available preparations to choose from as well.

YZXJ contains ingredients with heat-clearing and detoxifying properties such as Scutellaria barbata, Bittersweet herb, and Herba artemisiae scopariae. Scutellaria barbata, a traditional anticancer Chinese medicine, has been found to have the additional effect of anti-inflammation and anti-infection in recent years. Diterpenoid alkaloids and 6-methoxynaringenin in the Scutellaria barbata extracts had the strongest effect on downregulating the secretion of NO, PE2, IL-6, IL-1β induced by LPS and P-JNK signaling pathway activation [42–44]. Moreover, the water extracts of Bittersweet herb and Herba artemisiae scopariae can alleviate inflammation by inhibition of NF-κB pathway that reduces the generation of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and IL-6 [45–47]. Other components in YAXJ such as Astragalus membranaceus have the effects of invigorating Qi, generating Yang, strengthening exterior, and stopping sweating, often used for the rehabilitation of patients with weak constitution. However, recent studies have found that the extract Astragalus polysaccharide can inhibit the production of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α or IL-1β through NF-κB, ERK, JNK, and other pathways to regulate immune function and reduce intestinal inflammation [48, 49]. In addition, Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide extracted from Ganoderma, one of the components of YZXJ, have beneficial effects on improving CRF in breast cancer patients without any significant adverse effect [50]. Further animal experiments suggested that, in addition to slowing down the growth of tumors, Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides can also prolong exhausting swimming time of tumor-bearing mice through decreasing the level of TNF-a or IL-6 induced by cisplatin and upregulating the SOD activity in the muscle [51].

Except for the inflammation, oxidative stress, energy metabolism, and abnormal hormone levels are also important mechanisms for the development of CRF, especially physical fatigue. Emerging evidence demonstrated that persistent fatigue occurs when the body kinetic energy consumption exceeds the cells energy supply capacity. Physical fatigue is almost accompanied by metabolic disorders, mainly liver glycogen and muscle glycogen metabolism [52]. In fact, behind the metabolic disorders we can still see the “shadow” of inflammatory responses, which affect the host metabolism and neuroendocrine reactions and induce or promote fatigue symptoms [53]. The tumor itself, as an inflammatory response, often appears simultaneously with a reduction in hepatic glycogen [54, 55]. Therefore, we examined the effect of YZXJ on hepatic glycogen levels. As expected, YZXJ can increase the reserve of liver glycogen, which is consistent with the literature. A number of studies have confirmed that increasing glycogen levels may alleviate fatigue; for example, hydrogen water drinking relieves fatigue by lowering blood sugar, lactic acid, BUN, and increasing liver glycogen [56]. In the mouse swimming experiment, acute valine supplementation helps maintain liver glycogen and blood sugar levels and increases spontaneous activity, which could contribute to relieving postexercise fatigue [57]. For a long time, people have tried to adopt traditional Chinese medicine methods such as Ginseng and fungus to treat fatigue and achieved good results. Basic research found that most of these methods increase glycogen content in liver and muscles [58–60]. In addition to ingredients that add supplemental energy such as Ginseng and ingredients like Eupolyphaga seu steleophaga that reduce tissue oxygen consumption, YZXJ relieves fatigue from both entry and exit.

Flora imbalance is involved in the development of CRC by affecting inflammatory response or immune status; on the other hand, it can induce fatigue through the inflammatory or metabolic pathways. Among the numerous bacteria associated with CRC, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis (Prevotella), Shigella, Helicobacter, etc. can promote inflammation, conversely, Clostridium, especially Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, can inhibit the inflammatory response. Meanwhile, the proinflammatory intestinal flora mentioned above can cause fatigue, whereas Clostridium, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium can alleviate fatigue. In view of these above, people are trying to treat CRF from the perspective of regulating intestinal microbiota.

In order to study the effect of YZXJ on intestinal microbiota, we used a method of colon cancer orthotopic transplantation in BALB/c mice to restore the growth environment of colon cancer as much as possible. We found that the YZXJ group had a decrease in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, which was identical with those reported in literature. Studies have shown that the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes is related to fatigue, and the higher the ratio, the severer the fatigue, and vice versa [61–63]. At genus level, the abundance of Parabacteroides, unidentified Saprospiraceae, and Elizabethkingia in Bacteroidetes were increased and Arcobacter, Marinobacter, Alkanindiges, Sulfuricurvum, Haliangium, and Thiobacillus belonging to Proteobacteria were decreased in YZXJ group. A large amount of data confirmed that Bacteroides can promote the metabolism of ginsenoside that indirectly improves the state of physical fatigue [64, 65]. Proteobacteria mainly include Helicobacter and Shigella, both of them can promote the occurrence of CRC by inducing inflammatory reaction and also play an important role in causing CRF [66–68]. According to a research, Proteobacteria can affect the deglycosylated metabolism of panax notoginseng saponins via regulating the activities of glycosidases, while upregulation of Bacteroidetes may promote the redox metabolism of this drug through improving related enzymes activities in intestine [69].

There is still lack of systematic study in depth on the elevated effects of YZXJ on certain beneficial intestinal bacteria. However, it can be seen that some components of YZXJ have an antimicrobial effect. Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid, the main components of YZXJ, extracted from Fructus ligustri lucidi, can inhibit the transcription of genes related to peptidoglycan biosynthesis, thereby preventing bacterial growth which manifested a strong lethality on Streptococcus [70]. Other ingredients, such as Mock strawberry herb, can directly inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumor cells and can also eliminate pathogenic bacteria like Streptococcus [71]. The active ingredient of Scutellaria barbata is essential oil, which has an elimination effect on a variety of bacteria, especially gram-positive bacteria including methicillin-resistant Staphlococcus aureus [72]. Changes in the intestinal microbiota initiate both inflammatory reactions and metabolism disorders, glucose metabolism in especial, which ultimately induce CRF.

This study did not perform metabolomics analysis and in vitro experiments that could not fully elucidate the exact mechanism of YZXJ on alleviating CRF. Nevertheless, this study has clarified that YZXJ was obviously effective in improving physical and mental fatigue in mice with orthotopic colorectal cancer, from which we almost can speculate that this effect is exerted by altering intestinal microbiota, reducing inflammation, and improving metabolism, which hence shows good prospects for application.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by Hebei Provincial Administration of traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project (Project number: 2018082). We are thankful to Yong Gao and Yiling Wu who provided expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Stasi R., Abriani L., Beccaglia P., Terzoli E., Amadori S. Cancer-related fatigue: evolving concepts in evaluation and treatment. Cancer. 2003;98(9):1786–1801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banipal R. P. S., Singh H., Singh B. Assessment of cancer-related fatigue among cancer patients receiving various therapies: A cross-sectional observational study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care. 2017;23(2):207–211. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_135_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger A. M., Mooney K., Alvarez-Perez A., et al. Cancer-related fatigue, version 2.2015. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2015;13(8):1012–1039. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnio S., Di Stefano R. F., Novello S. Fatigue in lung cancer patients: Symptom burden and management of challenges. Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy. 2016;7:73–82. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S85334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan J. L., Carroll J. K., Ryan E. P., Mustian K. M., Fiscella K., Morrow G. R. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. The Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortimer J. E., Waliany S., Dieli-Conwright C. M., et al. Objective physical and mental markers of self-reported fatigue in women undergoing (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(10):1810–1816. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Higgins C. M., Brady B., O’Connor B., Walsh D., Reilly R. B. The pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue: current controversies. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26(10):3353–3364. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei J. N., Li S. X. The relationship between nutritional risks and cancer-related fatigue in patients with colorectal cancer fast-track surgery. Cancer Nursing. 2017;41(6):E41–E47. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolak A., Kamińska M., Wysokińska E., et al. The problem of fatigue in patients suffering from neoplastic disease. Contemporary Oncology. 2017;21(2):131–135. doi: 10.5114/wo.2017.68621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neefjes E. C. W., van der Vorst M. J. D. L., Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S., Verheul H. M. W. Aiming for a better understanding and management of cancer-related fatigue. The Oncologist. 2013;18(10):1135–1143. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaVoy E. C., Fagundes C. P., Dantzer R. Exercise, inflammation, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Exercise Immunology Review. 2016;22:82–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanken K., Sander C., Qaiser L., et al. Salivary IL-1ß as an objective measure for fatigue in multiple sclerosis? Frontiers in Neurology. 2018;9:p. 574. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fluge Ø., Mella O., Bruland O., et al. Metabolic profiling indicates impaired pyruvate dehydrogenase function in myalgic encephalopathy/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. 2016;1(21) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89376.e89376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomas C., Newton J. Metabolic abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a mini-review. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2018;46(3):547–553. doi: 10.1042/BST20170503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu C., Lv J., Lo Y. M., Cui S. W., Hu X., Fan M. Effects of oat β-glucan on endurance exercise and its anti-fatigue properties in trained rats. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;92(2):1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straub R. H. The brain and immune system prompt energy shortage in chronic inflammation and ageing. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2017;13(12):743–751. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacourt T. E., Vichaya E. G., Chiu G. S., Dantzer R., Heijnen C. J. The high costs of low-grade inflammation: Persistent fatigue as a consequence of reduced cellular-energy availability and non-adaptive energy expenditure. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2018;12:p. 78. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lleonart M. E., Grodzicki R., Graifer D. M., Lyakhovich A. Mitochondrial dysfunction and potential anticancer therapy. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2017;37(6):1275–1298. doi: 10.1002/med.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan Å., Nord C. E., Evengård B. Effect of supplement with lactic-acid producing bacteria on fatigue and physical activity in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Nutrition Journal. 2009;8(1):p. 4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris G., Berk M., Carvalho A. F., Caso J. R., Sanz Y., Maes M. The role of microbiota and intestinal permeability in the pathophysiology of autoimmune and neuroimmune processes with an emphasis on inflammatory bowel disease type 1 diabetes and chronic fatigue syndrome. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2016;22(40):6058–6075. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160914182822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J., Kato I. Gut microbiota, inflammation and colorectal cancer. Genes and Diseases. 2016;3(2):130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong T. N. Y., Wang X., Nakatsu G., et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):383–390.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paulsen J. A., Ptacek T. S., Carter S. J., et al. Gut microbiota composition associated with alterations in cardiorespiratory fitness and psychosocial outcomes among breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017;25(5):1563–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang H., Kwon M., Chang Y., et al. Fecal microbiota differences according to the risk of advanced colorectal neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2018 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustian K. M., Alfano C. M., Heckler C., et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue: A meta-analysis. JAMA Oncology. 2017;3(7):961–968. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessels E., Husson O., van der Feltz-Cornelis C. M. The effect of exercise on cancer-related fatigue in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2018;14:479–494. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S150464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mücke M., Mochamat ., Cuhls H., et al. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue associated with palliative care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(5) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006788.pub3.CD006788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomlinson D., Robinson P. D., Oberoi S., et al. Pharmacologic interventions for fatigue in cancer and transplantation: a meta-analysis. Current Oncology. 2018;25(2):e152–e167. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Arye E., Dahan O., Shalom-Sharabi I., Samuels N. Inverse relationship between reduced fatigue and severity of anemia in oncology patients treated with integrative medicine: understanding the paradox. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26(12):4039–4048. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S., Jiang J. Anti-fatigue effects of active ingredients from traditional Chinese medicine: a review. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2017;24 doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170414164607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arring N. M., Millstine D., Marks L. A., Nail L. M. Ginseng as a treatment for fatigue: A systematic review. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2018;24(7):624–633. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao X., Xiao B., Shui S., Yang J., Huang R., Dong J. Metabolomics analysis of serum reveals the effect of Danggui Buxue Tang on fatigued mice induced by exhausting physical exercise. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2018;151:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shui S., Cai X., Huang R., Xiao B., Yang J. Metabonomic analysis of serum reveals antifatigue effects of Yi Guan Jian on fatigue mice using gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Biomedical Chromatography. 2018;32(2) doi: 10.1002/bmc.4085.e4085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y., Lin L., Li H., Hu Y., Tian L. Effects of acupuncture on cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26(2):415–425. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang W. G., Ye L., Ji K., et al. Antitumour effects of Yangzheng Xiaoji in human osteosarcoma: The pivotal role of focal adhesion kinase signalling. Oncology Reports. 2013;30(3):1405–1413. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W. G., Ye L., Ruge F., et al. YangZheng XiaoJi exerts anti-tumour growth effects by antagonising the effects of HGF and its receptor, cMET, in human lung cancer cells. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2015;13:p. 280. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0639-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bårdsen K., Nilsen M. M., Kvaløy J. T., Norheim K. B., Jonsson G., Omdal R. Heat shock proteins and chronic fatigue in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2016;22(3):162–167. doi: 10.1177/1753425916633236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milrad S. F., Hall D. L., Jutagir D. R., et al. Poor sleep quality is associated with greater circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and severity and frequency of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) symptoms in women. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2017;303:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adzic M., Brkic Z., Mitic M., et al. Therapeutic strategies for treatment of inflammation-related depression. Current Neuropharmacology. 2018;16(2):176–209. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170828163048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nam S., Kim H., Jeong H. Anti-fatigue effect by active dipeptides of fermented porcine placenta through inhibiting the inflammatory and oxidative reactions. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2016;84:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park S. H., Jang S., Son E., et al. Polygonum aviculare L. extract reduces fatigue by inhibiting neuroinflammation in restraint-stressed mice. Phytomedicine. 2018;42:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai C., Lin C., Hsu C., et al. Using the Chinese herb Scutellaria barbata against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: in vitro and in vivo studies. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1):p. 96. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2151-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H.-L., Kao T.-H., Shiau C.-Y., Chen B.-H. Functional components in Scutellaria barbata D. Don with anti-inflammatory activity on RAW 264.7 cells. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2018;26(1):31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee S. R., Kim M.-S., Kim S., Hwang K. W., Park S.-Y. Constituents from scutellaria barbata inhibiting nitric oxide production in LPS-stimulated microglial cells. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2017;14(11) doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201700231.e1700231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu J.-Y., Lin H.-H., Hsu C.-C., Chen B.-C., Chen J.-H. Aqueous extract of pepino (Solanum muriactum ait) leaves ameliorate lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(7) doi: 10.3390/nu10070931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeo D., Hwang S. J., Kim W. J., Youn H., Lee H. The aqueous extract from Artemisia capillaris inhibits acute gastric mucosal injury by inhibition of ROS and NF-kB. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;99:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jang M., Jeong S. W., Kim B. K., et al. Extraction optimization for obtaining Artemisia capillaris Extract with high anti-inflammatory activity in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/872718.872718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan Y., Sun M., Li K. Astragalus mongholicus polysaccharide inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced production of TNF-α and interleukin-8. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;15(29):3676–3680. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He X., Shu J., Xu L., Lu C., Lu A. Inhibitory effect of Astragalus polysaccharides on lipopolysaccharide- induced TNF-α and IL-1β production in THP-1 cells. Molecules. 2012;17(3):3155–3164. doi: 10.3390/molecules17033155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao H., Zhang Q., Zhao L., Huang X., Wang J., Kang X. Spore powder of ganoderma lucidum improves cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients undergoing endocrine therapy: a pilot clinical trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:8. doi: 10.1155/2012/809614.809614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouyang M.-Z., Lin L.-Z., Lv W.-J., et al. Effects of the polysaccharides extracted from Ganoderma lucidum on chemotherapy-related fatigue in mice. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016;91:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang G., Shirai N., Suzuki H. Relationship between the effect of dietary fat on swimming endurance and energy metabolism in aged mice. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2011;58(4):282–289. doi: 10.1159/000331213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lasselin J., Capuron L. Chronic low-grade inflammation in metabolic disorders: relevance for behavioral symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(2-3):95–101. doi: 10.1159/000356535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirai K., Ishiko O., Tisdale M. Mechanism of depletion of liver glycogen in cancer cachexia. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;241(1):49–52. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Narsale A. A., Enos R. T., Puppa M. J., et al. Liver inflammation and metabolic signaling in apcmin/+ mice: the role of cachexia progression. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119888.e0119888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ara J., Fadriquela A., Ahmed M. F., et al. Hydrogen water drinking exerts antifatigue effects in chronic forced swimming mice via antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities. BioMed Research International. 2018;2018:9. doi: 10.1155/2018/2571269.2571269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuda Y., Iwasawa K., Yamaguchi M. Acute supplementation of valine reduces fatigue during swimming exercise in rats. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2018;82(5):1–6. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2018.1438168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li D., Ren J.-W., Zhang T., et al. Anti-fatigue effects of small-molecule oligopeptides isolated from Panax quinquefolium L. in mice. Food & Function. 2018;9(8):4266–4273. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01658A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang X., Chu Q., Li L., et al. The anti-fatigue activities of Tuber melanosporum in a mouse model. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2018;15(3):3066–3073. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osman W. N. W., Mohamed S. Standardized Morinda citrifolia L. and Morinda elliptica L. leaf extracts alleviated fatigue by improving glycogen storage and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Phytotherapy Research. 2018;32(10):2078–2085. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Libertucci J., Dutta U., Kaur S., et al. Inflammation-related differences in mucosa-associated microbiota and intestinal barrier function in colonic Crohn’s disease. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2018;315(3):G420–G431. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00411.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishino K., Nishida A., Inoue R., et al. Analysis of endoscopic brush samples identified mucosa-associated dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;53(1):95–106. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pahwa R., Balderas M., Jialal I., Chen X., Luna R. A., Devaraj S. Gut microbiome and inflammation: a study of diabetic inflammasome-knockout mice. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2017;2017:5. doi: 10.1155/2017/6519785.6519785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang L., Li F., Qin W., Fu C., Zhang X. Changes in intestinal microbiota affect metabolism of ginsenoside Re. Biomedical Chromatography. 2018;32(10):p. e4284. doi: 10.1002/bmc.4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou S., Xu J., Zhu H., et al. Gut microbiota-involved mechanisms in enhancing systemic exposure of ginsenosides by coexisting polysaccharides in ginseng decoction. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep22474.22474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Almeida C. V., Taddei A., Amedei A. The controversial role of Enterococcus faecalis in colorectal cancer. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2018;11 doi: 10.1177/1756284818783606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y., Wang X., Zhou M., et al. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and Sirtuin-3 in colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2018;50(4):p. 21. doi: 10.1038/s12276-017-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stecher B. The roles of inflammation, nutrient availability and the commensal microbiota in enteric pathogen infection. Microbiology Spectrum. 2015;3(3) doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0008-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiao J., Chen H., Kang D., et al. Qualitatively and quantitatively investigating the regulation of intestinal microbiota on the metabolism of panax notoginseng saponins. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;194:324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park S. N., Lim Y. K., Choi M. H., et al. Antimicrobial mechanism of oleanolic and ursolic acids on streptococcus mutans UA159. Current Microbiology. 2018;75(1):11–19. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seleshe S., Lee J. S., Lee S., et al. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of ethanol extracts of three kinds of strawberries. Preventive Nutrition and Food Science. 2017;22(3):203–210. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2017.22.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu J., Lei J., Yu H., Cai X., Zou G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Scutellaria barbata. Phytochemistry. 2004;65(7):881–884. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.