Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic, incurable diseases which are often characterized by unpredictable flares and troubling symptoms which can interfere with a patient's ability to work. Accommodations in the workplace can help persons with IBD to cope with their illness and work effectively. We systematically reviewed all studies regarding workplace disability in IBD patients.

Summary

Systematic searches were undertaken on February 5 and March 5, 2018, for the following databases: PubMed, MEDLINE (Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL, for studies that addressed workplace needs, accommodations and adaptations using survey tools. Of 430 studies screened, 54 met initial eligibility criteria and then 6 studies were ultimately included, with a total of 7,700 participants. Five studies were quantitative, and 1 study was qualitative. Common themes were the importance of reasonable adjustments and accommodations in the workplace, mixed with the finding that a significant proportion reported that they had some difficulty arranging accommodations. Adaptations most required were access to a toilet or toilet breaks and time to go to medical appointments.

Key Messages

People with IBD often need accommodations, but many do not ask or have difficulty arranging it. Better resources are needed to inform people with IBD about the possibilities for workplace accommodations and practical strategies to request them.

Keywords: Accommodations, Crohn's disease, Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Workplace disability

Introduction

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, collectively called inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are chronic, incurable diseases that cause inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. IBD is characterized by unpredictable flares and troubling symptoms which can interfere with a patient's ability to work [1]. Because many patients develop IBD in their late teens or early 20s, this chronic disease can have a considerable impact on employment outcomes [2]. The incidence of IBD is stabilized in the western world, while the prevalence remains high. On the other hand, newly industrialized countries are facing a rising incidence and therefore the global burden of IBD keeps growing [3].

Much research has been undertaken on the impact of IBD on work-related outcomes, and most studies report that persons with IBD experience a high burden in work-related outcomes because of an increased frequency of sick leave, disability pension, and unemployment [4, 5, 6]. To measure health-related work productivity loss among patients, many studies use the Work Productivity Activity Impairment Questionnaire. This validated instrument assesses absenteeism and presenteeism and quantifies the amount of the limitation and its effect on work productivity [1, 7]. In addition to describing this impairment in terms of indirect costs and employment numbers, it is important to focus on work experiences of persons with IBD.

In a recent study of persons with IBD in the Netherlands, almost half of those who were working experienced hindrance related to their health problems in the previous 2 weeks. They reported difficulties such as concentration problems (72%), having to work at a slower pace than normal (78%), and having to seclude themselves from their colleagues (54%) [8]. A large survey from Japan demonstrated that the percentage of patients who had experienced at least one difficulty at work because of their IBD was 98.3% for ulcerative colitis and 98.8% for Crohn's disease [9].

Modifications at work can help people to cope with their illness and work effectively [10]. This has been shown in other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [11, 12]. The aim of the present study is to systematically review the literature regarding overcoming workplace disability in persons with IBD. This review aims to describe the accommodations and adaptations that persons with IBD request and how difficult it is to make these arrangements with their workplace. By investigating these workplace needs and accommodations, we hope to gain valuable information about the magnitude of the problem and how to overcome workplace disability, and thereby ultimately offer helpful information to IBD patients who are working or about to enter the workforce. An improved awareness of the strategies to help with the obstacles associated with IBD in the workplace can consequently improve employment and participation.

Method

Selection Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they (a) involved persons who were diagnosed with IBD and (b) participants were working or had been working adults; (c) assessed ways to overcome workplace disability by asking about accommodations and adaptations, (d) using a questionnaire or interview.

Exclusion Criteria

Database studies, studies that did not include information on addressing workplace difficulties, and studies only about number of sick days or costs.

Search Strategies

Systematic searches were undertaken on February 5 and March 5, 2018, for the following databases: PubMed, MEDLINE (Ovid) (online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000495293), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL. The search terms used for each of these databases are shown below. Manual searches using the reference list were also undertaken.

PubMed

(Inflammatory bowel disease OR ulcerative colitis OR Crohn's disease) AND (work[place] [dis]ability OR employment OR work participation OR sick leave OR absenteeism).

MEDLINE/Ovid

(Inflammatory bowel disease OR ulcerative colitis OR Crohn's disease) AND (work[place] OR [un]employment OR job satisfaction OR presenteeism OR absenteeism).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

(Inflammatory bowel disease OR ulcerative colitis OR Crohn's disease) AND (work[place] OR [un]employment OR job satisfaction OR presenteeism OR absenteeism).

CINAHL

(Inflammatory bowel disease OR ulcerative colitis OR Crohn's disease) AND (work[place] OR [un]employment OR job accommodation OR absenteeism OR presenteeism OR sick leave OR job satisfaction).

Results

Study Selection

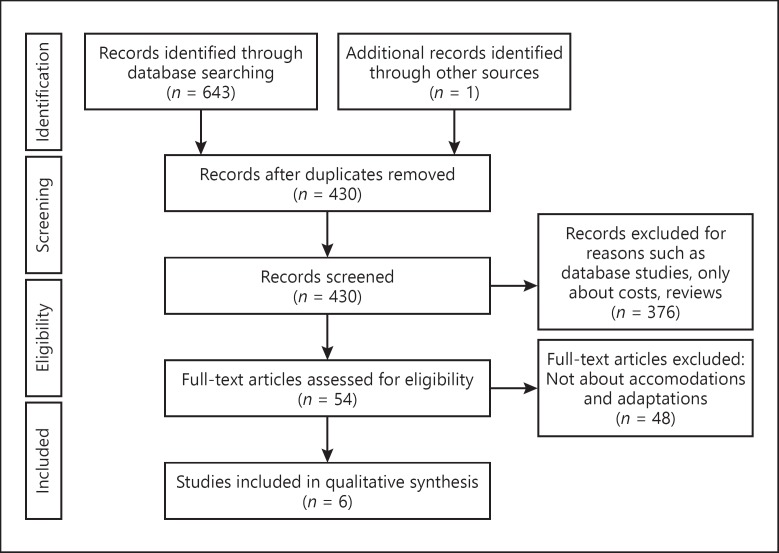

Figure 1 shows the study selection method. There were 309 results produced from PubMed, 195 from MEDLINE, 119 from CINAHL, and 20 from Cochrane Library. Duplicates were removed and articles' titles and abstracts were analyzed: studies outside the criteria (described above) were excluded. Many papers from the databases were analyzed before some were excluded for reasons specified in Figure 1. The reference lists of all articles were searched. In total, 6 studies were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Summary of Research Outcomes

Summary of the Research Methods

Table 1 shows the 6 included papers and their outcomes. Three studies reported on the ability to work from home/telecommuting [13, 14, 15]; 4 studies reported on working flexible hours or have a flexible starting time [13, 14, 15, 16]; 2 studies reported on the chance to take a break to rest or go to the toilet [13, 16], and 1 about easy access to a toilet [16]; 3 studies reported on the ability attend a medical appointment during work [13, 16, 17]; and 3 studies reported on the ability to work fewer days each week or part-time [14, 15, 16]. A qualitative study [18] reported on the need for different aspects of flexibility and adaptations in the physical environment. Three studies were performed in Europe [13, 14, 17], 2 in Canada [16, 18], and 1 in the USA [15]. Two studies reported a response rate [16, 17]. Three studies included persons in the analyses who were currently employed or had been employed [13, 15, 17, 18], 1 study included patients who had symptoms while working [16], and 1 study did not define their IBD patient population [14]. Sample size ranged from 45 to 4,670 participants.

Table 1.

Studies describing accommodations and adaptations to overcome workplace disability in IBD patients

| First author, year, country | Patients, n | Details, n | Response rate (study total) | Method | Outcomes reported quantitatively |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| working from home/telecommuting | flexible hours (or start time) | chance to take a break (rest or toilet) | easy access to toilet | time for medical appointment | reduced work days each week/part-time | |||||

| Gay [13], 2011, UK | 1,304/1,906 | currently employed | − | questionnaire | × | × | × | × | ||

| Chhibba [16], 2017, Canada | 881/1,143 | experienced symptoms at some time while working | 46% | questionnaire | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Lonnfors [14], 2014, Europe (25 countries) | 4,670 | undefined | − | questionnaire | × | × | × | |||

| Zand [15], 2015, US | 152/440 | currently employed | − | questionnaire | × | × | × | |||

| Mayberry [17], 1992, UK | 46 | currently employed | 70% | questionnaire | × | |||||

| Restall [18], 2016, Canadaa | 45 | employed/previously employed | individual interviews | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

Qualitative, so no listed outcomes reported.

Summary of the Research Results

In a large study by Gay et al. [13], members of Crohn's and Colitis UK were approached via online and postal questionnaires. The questionnaire consisted of different sections for patients who were employed, not working, or who had not yet entered the workforce. Of 1,906 participants 1,314 were employed. The survey asked the employed respondents about how much their employers supported them in carrying out their job while having IBD.

Another large mailed survey was performed by Chhibba et al. [16], where participants were recruited from the population-based University of Manitoba Research Registry in Canada. Of persons who completed the questionnaire (n = 1,143), 881 stated that they had experienced IBD symptoms while working at paid employment and these were included in the analyses. Respondents were asked about the accommodations that were needed in the workplace and how these were managed. More than 90% needed workplace accommodations.

Lönnfors et al. [14] reported on the impact of IBD in the workplace for respondents from 25 European countries, using an online questionnaire from the website of the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Association (EFCCA). A total of 4,670 respondents were included.

Zand et al. [15] described the experiences of 152 employed persons from an outpatient clinic in a tertiary IBD center in the USA. Only 34% were able to make work adjustments to avoid taking time off due to their IBD; 59% had not made any such adjustments and 23% did not have the possibility to make such adjustments. A smaller study from the UK in 1992 (n = 46) from Mayberry et al. [17] reported only on the possibility for IBD patients to attend outpatient appointments during work time.

Working from Home. Three studies investigated the ability to work from home. In one of them, 41% of the employed respondents indicated that this was important to them, but only 1 in 5 employed respondents (21%) cited working from home as an option [13]. In another study 10% of the respondents changed their working life to work from home [14]. Sixteen percent of employed participants made the adjustment to work from home [15].

Flexible Hours (or Start Time). Four studies reported on working flexible hours. In a large study, the biggest gap between the need for an adjustment and the availability of it was the ability to work flexible hours, which was said to be important to 65% of the employed respondents, but only 41% of the employers provided this [13]. Flexible or reduced hours of the workday were necessary for 47% and were available for 25% of those needing them. For 30% who needed flexible or reduced hours it was somewhat or very difficult to arrange. Flexibility in start time and work hours was needed by 44% and of those who asked for it, it was available to 26% but difficult to arrange in 30% [16]. Of another study's respondents, 15% worked flexible hours [14], and in a smaller study 25% of the participants worked flexible hours [15].

Chance to Take a Break (Rest or Toilet). Two large studies reported on the ability to take a break to rest or to go to the toilet. Eighty-three percent of the employed respondents said that they needed frequent toilet breaks, but nearly one third of the workers reported their employers did not provide this (29%) [13]. Fifty-four percent of those included stated that they needed the chance to take a break (30–60 min) when not feeling well and this was available to 26% when asked for it [16].

Easy Access to Toilet. One study described the importance of easy access to a suitable toilet. This was needed by 71% of the respondents but was available to just 43%. This accommodation was not very difficult to arrange, with 22% of the participants who needed it answering that it was somewhat or very difficult to arrange when asked [16].

Time for Medical Appointment. Three studies reported on the ability to take time off for medical appointments. For the two largest studies this was the most important adjustment [13, 16]. It was important to 88% but available to 69% of the employed participants in the study by Gay et al. [13]. In the survey by Chhibba et al. [16], it was needed by 81%, available for 72% when they asked for it, and was the least difficult to arrange. Only 11% of those who needed time off to attend a medical appointment responded that it was somewhat or very difficult to arrange. In a small study, 78% of the employers of persons with IBD allowed patients to attend outpatient appointments during work time [17].

Reduced Workdays Each Week/Part-Time. Three studies investigated how much accommodation for reduced workdays each week was required. In the first study, this was required by 35% of the participants, available when asked for by only 17%, and difficult to arrange in 35% of the patients who needed this accommodation [16]. In the other studies, 15% [14] and 11% [15] worked part-time.

In the only qualitative study included from Restall et al. [18], 45 patients who were employed or previously employed were studied. Participants had undergone an individual face-to-face interview to obtain an in-depth understanding of personal experiences, strategies, and environmental support with regard to workplace issues. Regarding the need for accommodations, they stated that modifications in flexibility were found to be important, including flexible work hours, reduced work hours, and self-directed timing of breaks if needed. Also, adaptations in the physical environment like access to the toilet, light duties option, flexibility in body positioning while working, flexibility in workplace, and a quiet room for rest periods were believed to facilitate their work participation. They especially identified the importance of the proximity of a toilet.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review describing how persons with IBD overcome workplace disability by arranging workplace accommodations and adaptations when needed. Common themes across the studies were the importance of reasonable adjustments and accommodations in the workplace for people with IBD, mixed with the finding that a significant proportion of participants reported that they had some difficulty arranging accommodations. For example, a study reported that 90% of persons with IBD who had symptoms at some time during their working life required accommodations. However, many found workplace accommodations difficult to arrange or did not ask for it, while half found it relatively easy to arrange [16]. Two studies reported that only 34% [15] and 40% [14], respectively, were able to make work adjustments to avoid taking time off due to their IBD. Two studies reported that the adaptations most required were access to a toilet or toilet breaks and time off to attend medical appointments [13, 16].

Persons with IBD are more likely to be unemployed compared to the general population [4]. This could in part be explained by a lack of workplace coping strategies available to those with IBD and a lack of understanding of employers. Gay et al. [13] reported that one third of the respondents worried about their employer not being flexible to their needs, and nearly two thirds did not feel fully supported by their employer to carry out their job with IBD (64%). Whilst the included studies were heterogeneous, it is reasonable to infer that there are many persons with IBD who do not get the workplace accommodations they need. The importance of rights and work policies, the relationship between an employee and supervisor, and workplace culture in seeking for and the granting of accommodations were described: “Participants noted the importance of a workplace that promoted acceptance, and of supervisors and managers who were aware of accommodation processes and options” [18]. Because IBD can be an invisible disease which is not always understood by an employer, raised awareness of IBD among employers and the subsequent availability of accommodations is important to keep affected persons at work, enhancing their well-being and incomes and facilitating their contribution to society. Better workplace accommodations could help more people with IBD return to work when off and stay in work.

To further enhance integration of persons with IBD in the workforce, job characteristics of importance for participants who had not yet entered the workforce were investigated [13]. Pre-employed persons considered the ability to take time off for medical appointments and frequent toilet breaks to be most important in their future job, which is in line with our results. IBD often affects young people who are already employed or who may be seeking employment. Therefore, young persons with IBD need support when entering the workplace in order to maximize their participation and contribution to society. Whilst all people, including those with IBD, should be encouraged to have high career aspirations, it is also important to be cognizant and realistic about their needs and the flexibility they need, especially if their IBD is poorly controlled. Relatedly, a significantly greater need for two or more accommodations for people working away from home was reported, compared to those who were self-employed or working from home (OR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.26–3.35) [16].

To compare IBD to other chronic diseases, we looked at a study concerning the availability, need, and use of workplace adaptations of workers with osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis [11]. The accommodation most reported was special equipment and adaptations of the workplace, with most respondents receiving some form of accommodation. This in comparison to frequent toilet breaks and the possibility of attending a medical appointment during work in patients with IBD. More than half of the participants with osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis needed flexible working hours, which was overall almost the same in the IBD patients. Over 60% of respondents stated they did not need the work at home arrangements (64.8%), which was also equal to the IBD patients included in this study. Among the osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis patients needing benefits or accommodations, many participants were able to use them, but overall this was more difficult in the accommodations requested by patients with IBD in this systematic review [11].

Limitations and Implications

This systematic review has a number of limitations. Firstly, only 6 studies were eligible for inclusion. However, 7,700 participants were included with only 2 studies having a small sample size [17, 18]. Two studies included participants from a patient support group [13, 14], which leads to an inherent bias in that people who join a support group may be different from those who do not. One study [15] recruited participants from an outpatient clinic in a tertiary IBD center, and hence may have included persons with more severe IBD who require more accommodations and adaptations at work. One study [14] used a questionnaire only accessible via a website, and may have excluded patients without internet access. Finally, the response rate was only reported in 2 studies [16, 17].

It is difficult to compare results due to heterogeneity between studies. Three studies only included persons who were currently employed [13, 15, 17], 1 study included persons who had ever been employed including past employment [18], and 1 included only those who had symptoms while working [16]. One study did not define their population [14]. Workplace accommodations were evaluated using different questions in each study, for example, the need for accommodations, their availability, the difficulty in arranging them, or the adjustments actually made were asked in different ways. The studies were performed in different countries, and therefore different workplace cultures and laws apply to each study. Study participants were from Canada, USA, and 25 countries in Europe. Therefore, it is unknown as to the needs for workplace accommodations and their availability from other jurisdictions, especially as the incidence of IBD is rising throughout the world [3]. More research is needed on workplace disability in different countries to allow comparisons and assist in developing a broad understanding of the need for and the availability of workplace accommodations and adaptions for persons with IBD globally.

To improve the current situation for the community, better education and more awareness is required. Booklets available for both employers and employees can provide them with more information concerning IBD and instructions regarding legislation and laws. These employment guides produced by patient groups are already used in the UK and need to become available in more jurisdictions [19, 20].

Conclusion

Persons with IBD often need workplace accommodations to allow them to participate in the workforce, but many do not ask for them or have difficulty arranging them. Improved resources are needed to inform people with IBD about the possibilities for workplace accommodations and practical strategies to request them. Information about employer and employee responsibilities regarding accommodations are also needed to allow employers to understand the needs of their employees and the ways in which they can be effective in the workplace. Accommodations such as easy access to toilets or time for medical appointments could make a significant difference to those either working or looking for work. Persons with IBD may need to consider career paths that fit their needs in terms of accommodations (e.g., self-employment) as well as employers who have a sufficient understanding of IBD where possible.

Disclosure Statement

No funding was received for this study. Dr. Bernstein is supported in part by the Bingham Chair in Gastroenterology. He serves on advisory boards for Abbvie Canada, Janssen Canada, Shire Canada, Takeda Canada, Pfizer, and Ferring Canada, and has consulted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals and 4-D Pharma. He has received educational grants from Abbvie Canada, Pfizer Canada, Shire Canada, Takeda Canada, and Janssen Canada, and is on the speaker's panel for Ferring Canada and Shire Canada. For the remaining authors no conflict of interest exists.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Reilly MC, Gerlier L, Brabant Y, Brown M. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in Crohn's disease. Clin Ther. 2008 Feb;30((2)):393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Matary W, Dufault B, Moroz SP, Schellenberg J, Bernstein CN. Education, Employment, Income, and Marital Status Among Adults Diagnosed With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases During Childhood or Adolescence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Apr;15((4)):518–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390((10114)):2769–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Büsch K, da Silva SA, Holton M, Rabacow FM, Khalili H, Ludvigsson JF. Sick leave and disability pension in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014 Nov;8((11)):1362–77. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spekhorst LM, Oldenburg B, van Bodegraven AA, de Jong DJ, Imhann F, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, et al. Parelsnoer Institute and the Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis Prevalence of- and risk factors for work disability in Dutch patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;23((46)):8182–92. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i46.8182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marri SR, Buchman AL. The education and employment status of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Feb;11((2)):171–7. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993 Nov;4((5)):353–65. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Boer AG, Bennebroek Evertsz' F, Stokkers PC, Bockting CL, Sanderman R, Hommes DW, et al. Employment status, difficulties at work and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Oct;28((10)):1130–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito M, Togari T, Park MJ, Yamazaki Y. Difficulties at work experienced by patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and factors relevant to work motivation and depression. Japanese Journal of Health and Human Ecology. 2008;74((6)):290–310. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundar V. Operationalizing workplace accommodations for individuals with disabilities: A scoping review. Work. 2017;56((1)):135–55. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gignac MA, Cao X, McAlpine J. Availability, need for, and use of work accommodations and benefits: are they related to employment outcomes in people with arthritis? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015 May;67((6)):855–64. doi: 10.1002/acr.22508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gignac MA, Ibrahim S, Smith PM, Kristman V, Beaton DE, Mustard CA. The Role of Sex, Gender, Health Factors, and Job Context in Workplace Accommodation Use Among Men and Women with Arthritis. Ann Work Expo Health. 2018 Apr;62((4)):490–504. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxx115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay Mea . Crohn's and Colitis UK. 2011. Crohn's, Colitis and Employment- from Career Aspirations to Reality. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, Avedano L. IBD and health-related quality of life— discovering the true impact. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014 Oct;8((10)):1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zand A, van Deen WK, Inserra EK, Hall L, Kane E, Centeno A, et al. Presenteeism in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Hidden Problem with Significant Economic Impact. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Jul;21((7)):1623–30. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chhibba T, Walker JR, Sexton K, Restall G, Ivekovic M, Shafer LA, et al. Workplace Accommodation for Persons With IBD: What Is Needed and What Is Accessed. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Oct;15((10)):1589–1595.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayberry MK, Probert C, Srivastava E, Rhodes J, Mayberry JF. Perceived discrimination in education and employment by people with Crohn's disease: a case control study of educational achievement and employment. Gut. 1992 Mar;33((3)):312–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Restall GJ, Simms AM, Walker JR, Graff LA, Sexton KA, Rogala L, et al. Understanding Work Experiences of People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Jul;22((7)):1688–97. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crohn's & Colitis UK Employment and IBD: A Guide for Employees - Edition 6. 2017 Available from: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-inflammatory-bowel-disease/publications/employment-ibd-a-guide-for-employees. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crohn's & Colitis UK Employment and IBD: A Guide for Employers - Edition 4. 2017 Available from: https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-inflammatory-bowel-disease/publications/employment-ibd-a-guide-for-employers. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data