Abstract

Background

Eight percent of the human genome consists of human endogenous retroviruses (HERV). These genetic elements are remnants of ancient retroviral germ-line infections. Altered HERV expression is associated with several chronic inflammatory diseases. A physiological role of the HERV-derived proteins syncytin-1 and -2 has been described for the integrity of the human placental cell layer in terms of maintaining feto-maternal tolerance. The aim of this project was to investigate HERV expression in Crohn's disease (CD) with a further focus on syncytins in the gut.

Material and Methods

Seventy-four ileal and colonic tissue samples of CD patients and healthy controls have been investigated for mRNA expression of major HERV groups by a comprehensive microarray screening. The most prominent differences have been validated by qRT-PCR. Immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western Blot (WB) and qRT-PCR were performed for syncytin-1 and -2.

Results

HERV microarray screening revealed a distinct expression profile in ileal and colonic tissue, as well as differential expression in CD compared to healthy controls. qRT-PCR validated differential expression of at least 3 HERV-groups in CD. qRT-PCR, IHC and WB showed a tissue-dependent diminished epithelial expression of syncytins in inflamed CD.

Conclusion

For the first time, HERV expression has been comprehensively studied in the gut. Between CD and healthy controls we could show a tissue dependent differential HERV expression profile. Notably, we could show that syncytin-1 and -2 are expressed in the epithelial layer in ileal and colonic tissue samples, whereas their diminished tissue-dependent expression in inflamed CD might modulate inflammatory processes at the gut barrier.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, Human endogenous retroviruses, Envelope protein, Syncytin-1, Syncytin-2

Introduction

Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) are remnants of ancient exogenous retroviral germ line infections during evolution. With 8–9%, they represent a substantial group of repetitive elements of the human genome [1, 2, 3, 4]. They consist, for example, of regulatory (promotor/enhancer elements) long terminal repeats (LTRs), pol (viral polymerase) and env sequences encoding for envelope proteins [5]. The classification of HERVs is based on homolog sequences of the polymerase (pol)-gene, thereby dividing them into 3 major classes with several defined groups (e.g., see Fig. 1) [6]. Even though HERVs are not infectious [7], LTRs are still regulatory active and can influence neighbouring genes, connecting HERVs to many malignant and inflammatory diseases. In these lines, HERVs have been proposed as modulators of pathological gene transcription or molecular mimicry on the protein level, involving them in physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms [5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15].

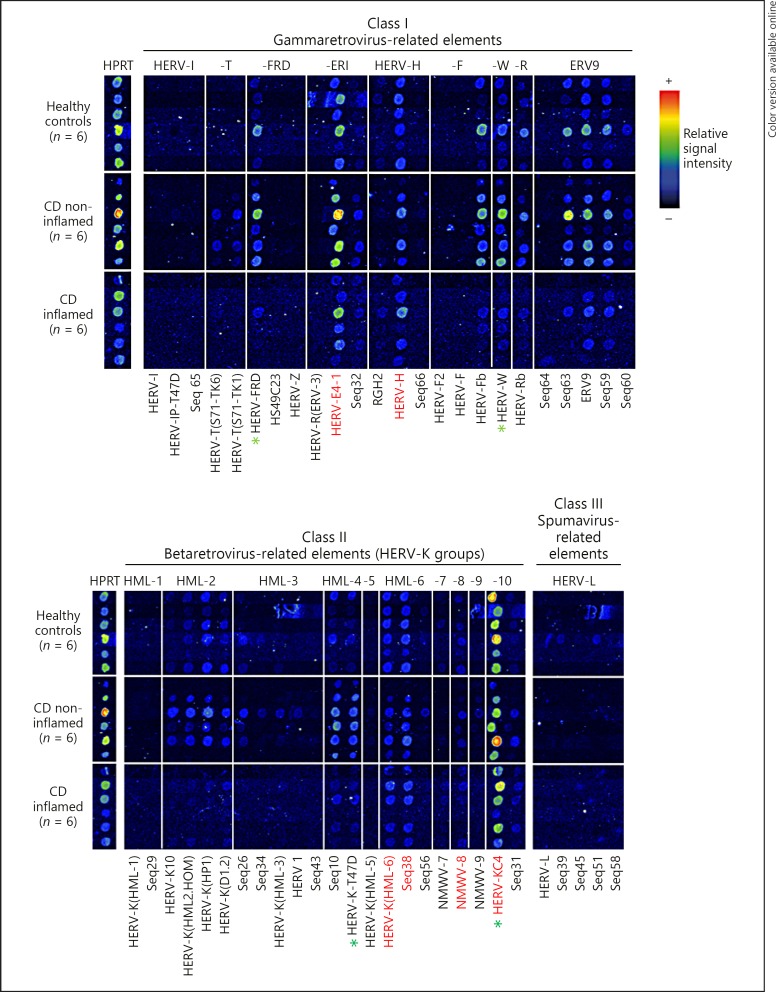

Fig. 1.

RetroArray analysis of HERV expression patterns in colonic tissue. The digitally aligned HERV activity profiles represent samples of 6 different individuals per investigated group (healthy controls; inflamed Crohn's disease [CD]; non-inflamed CD). HERV subgroups defining the colonic core signature (irrespective of disease or inflammation state) are emphasized with red letters. HPRT served as housekeeping gene for internal control. Although false colour mapping was used for improved image visualization, weak signals may be unrecognizable in the figure. Core transcription pattern was therefore confirmed by densitometry (data not shown). Green asterisks highlight HERV subgroups showing the most prominent differences between healthy controls and CD (qualitatively and in densitometry [also see Fig. 3]).

The most important physiological role of HERVs described so far, is their involvement in human placentation. The HERV-Wenv and HERV-FRDenv derived proteins syncytin-1 and -2 are due to their fusogenic properties necessary for the fusion of trophoblasts to syncytiotrophoblasts as core elements of the human placenta [16]. Furthermore, HERV envelope proteins like syncytin-2 have a highly conserved region called the immunosuppressive domain (ISD), which seems to be important for materno-fetal immune tolerance at the fetal sited cell layer of the placenta [17]. Additionally, the ISD peptide has immunosuppressive properties on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and, for example, in mouse models of skin or peritoneal inflammation [18, 19, 20]. A diminished expression of syncytins is related to preeclampsia [21].

Most striking environmental influences, for example, smoking, viruses or bacteria as well as inflammatory transcription factors have influence on HERV expression [14, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. In Crohn's disease (CD), the disruption of the intestinal barrier and environmental contact to millions of gut bacteria/viruses as well as nutrition factors is in the centre stage of the disease. CD is shaped by genetic as well as environmental conditions [28, 29]. Therefore, one could hypothesize that these interrelations can contribute to different HERV expression profiles, which in turn influence the phenotypic appearance of CD.

To study the possible role of HERVs in CD, we investigated HERV expression in CD patients and healthy controls. We used a retrovirus-specific microarray chip (RetroArray), which allows an expression screening for all major HERV groups [30, 31]. With this approach, we established for the first time a tissue-specific HERV transcription profile in CD. The most striking differences were additionally analysed by subgroup specific qRT-PCR-assays. Furthermore, investigating syncytin-1 and -2 on the mRNA and protein level in the gut, we could demonstrate a tissue-specific reduction of their expression in acute inflamed CD.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The diagnosis of CD was based on clinical, radiological and endoscopic findings according to the European guidelines [32]. All patients gave their written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Tübingen (Germany). A total of 74 tissue samples (ileal/colonic controls and inflamed/non-inflamed CD) were used for qRT-PCR (n = 74) and RetroArray (n = 35/74) studies. For patient characteristics, see Table 1. All colonic biopsies were from the sigmoid colon and all ileal samples from the terminal ileum. After endoscopy, biopsies were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and further prepared as described below. All samples were collected at the Robert-Bosch-Hospital, Stuttgart, Germany. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Western Blot (WB), additional 30 biopsies were used (ileal/colonic controls and inflamed/non-inflamed CD; 5 biopsies per group).

Table 1.

mRNA analysis – patient characteristics

| Controls | CD remission | CD active | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 24 | 30 | 20 |

| Age, years, mean (range) | 42 (19) | 39 (13) | 33 (14) |

| CRP, mg/L, mean (range) | 9 (19) | 9 (11) | 25 (22) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 | 17 | 8 |

| Female | 16 | 13 | 12 |

| Age at CD diagnosis | |||

| <40 years | 24 | 15 | |

| »40 years | 6 | 5 | |

| Localization (Montreal-Classification) | |||

| L1 (ileal) | 6 | 3 | |

| L2 (colonic) | 4 | 2 | |

| L3 (ileocolonic) | 20 | 15 | |

| L4 (+ upper GI) | 1 | 1 | |

| Behavior | |||

| Nonstricturing/penetrating | 10 | 10 | |

| Stricturing | 13 | 8 | |

| Penetrating | 7 | 2 | |

| Perianal disease | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical treatment for CD at time-point of endoscopy* | |||

| No therapy | 10 | 4 | |

| Oral 5-ASA | 6 | 4 | |

| Systemic steroids | 11 | 12 | |

| Oral budesonide | 6 | 3 | |

| Thiopurines | 9 | 7 | |

| Methotrexate | 2 | 1 | |

| Tacrolimus | 1 | 1 | |

| Anti-TNF-α | 4 | 1 | |

CRP, C-reactive protein; CD, Crohn's disease; GI, gastrointestinal; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α.

Some patients received more than one drug at the time-point of endoscopy.

RNA Preparation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturers' protocol. RNA quality was checked with the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For removal of genomic DNA, all mRNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase (Promega, Mannheim). Afterwards, 25 ng of each mRNA probe was tested by PCR with mixed oligo primers (MOP) [31] omitting the reverse transcription step. Only mRNA probes negative for amplification products were used for reverse transcription and MOP multiplex PCR as well as all following RetroArray and qRT-PCR experiments. cDNA synthesis of mRNA (2 µg) was performed with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers' protocol.

Retrovirus-Specific Microarray Experiments (RetroArray)

In the RetroArray workflow, in terms of amplification and labelling of hybridization probes by MOP PCR, all steps of microarray preparation, hybridization and post-processing were performed as described previously [30, 33]. The used microarray consists of 50 HERV-derived sequences representing the 20 major HERV groups [34]. The hybridized arrays consist of triplicates of the same array on the same chip. Only arrays with reproducible hybridization patterns within the triplicates were further evaluated. At the end of all steps, hybridized RetroArrays were scanned using an Affymetrix GMS-418 scanner (laser power setting, 100%; gain 50%) and the resulting 16-bit TIFF (tagged image file format) files were qualitatively and semi-quantitatively (densitometry) analysed using ImaGene 4.0 software (BioDiscovery, Inc., USA). As described previously, the discrimination between positive and negative signals was made based on an arbitrary cut-off value corresponding to greater than twofold background intensity (signal cut-off calculation) [33]. An HERV group is considered active, if at least one subgroup sequence is positive. In semi-quantitative densitometry, HERV signals were normalized to HPRT as a housekeeping gene, showing the most consistent transcript levels in the investigated probes. Notably, each positive RetroArray signal might represent multiple genomic HERV loci, assigned to multi-copy HERV elements spread over the human genome.

Quantification of HERV Transcripts by qRT-PCR

For mRNA quantification, real-time PCR was performed in an SYBR Green fluorescence temperature cycler (LightCycler, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). As template, 1 µL of cDNA (25 ng RNA equivalent) was used. For amplification of pol sequences, HERV subgroup specific pol primers were used as described in Table 2. In general, HERV subgroup-specific qRT-PCR primers were designed in such a way that for each HERV one primer matched the RetroArray capture probe sequence, whereas the second primer was located to a region that exhibits only marginal similarity among different HERV-taxa [30, 34]. Primers for HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) and HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) were chosen according to de Parseval et al. [35]. For HERV-FRD (group HERV-FRD), HERV-K-T47D (group HERV-K [HML-4]), HERV-KC4 (group HERV-K [HML-10]), HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) and HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) specific plasmids were used as controls and to quantify transcripts by standard curve analysis (serial dilution of plasmids). For all experiments, normalization was performed using β-actin as internal standard. Plasmids for each product were generated with the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the supplier's protocol. PCR-amplified DNA fragments were confirmed by sequencing, in terms of specificity to the sequence of interest using BLAST (basic local alignment search tool from the national center for biotechnology information [USA]). β-Actin and interleukin-8 (IL-8) transcripts were amplified and measured with gene-specific plasmids as described previously [36]. For HERV-W (group HERV-W), no specific plasmid could be found because of a high number of mutations. We quantified HERV-W transcription by the ddCT method, with normalization to β-actin and relative to transcription to defined healthy controls (colon/ileum) [37]. To confirm that specific products were amplified, the PCRs were further analysed by melting curve analysis and by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primer pairs used for qRT-PCR

| Product | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | GCCAACCGCGAGAAGATGA | CATCACGATGCCAGTGGTA |

| IL-8 | ATGACTTCCAAGCTGGCCGTGGC | TCTCAGCCCTCTTCAAAAACTTC |

| HERV-KC4 (HML-10) | GAATCTCTTCTAATTTGAACCTTTTGAGG | CCCACAGTTTGTCAAACTTTTGTAGGC |

| HERV-W | TGAGTCAATTCTCATACCTG | AGTTAAGAGTTCTTGGGTGG |

| HERV-FRD | AAAAAGGAAGAAGTTAACAGC | ATATAAAGACTTAGGTCCTGC |

| HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) | GTCGCTCAGGCTACATGC | AGTGAACGATGTAACATCGG |

| HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) | CCCCATCGTATAGGAGTCTT | CCCCATCAGACATACCAGTT |

| HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) | GCCTGCAAATAGTCTTCTTT | ATAGGGGCTATTCCCATTAG |

Primer pairs for syncytin-1 and syncytin-2 were chosen according to [35]. Primer pairs for β-actin and IL-8 were chosen according to [36]. Primer pairs for HERV-W and HERV-FRD were chosen according to [30]. Primer pairs for HERV-K-T47D were chosen according to [41]. Primer pairs for HERV-KC4 (HML-10) were chosen according to [55].

IHC and WB

A monoclonal mouse antibody directed against HERV-Wenv protein (GN-mAb_03) was generously provided by Dr. Hervé Perron (GeNeuro, Geneva, Switzerland). A rabbit polyclonal antibody targeting HERV-FRDenv, validated by the Human Protein Atlas project (www.proteinatlas.org), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the EnVisionTM Kit from Dako (Denmark) according to the manufacturer instructions.

As an antigen retrieval method, slides were steamed for 30 min in target retrieval solution, (Tris/EDTA buffer, pH 9, for HERV-Wenv, or citrate buffer, pH 6.1, for HERV-FRDenv [Dako, Denmark]). The primary antibody was incubated at 4°C overnight (antibody dilution HERV-Wenv 1: 10,000; HERV-FRDenv 1: 20). Hematoxylin counterstaining was performed on both sections.

For WB whole protein was isolated from ileal and colonic biopsies using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% TritonX-100) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein was dissolved in Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 min at 95°C. For electrophoresis, 30 µg protein was applied onto gels (Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free Protein Gels, Bio Rad) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in TBS (tris-buffered saline)-Tween and incubated in 1% nonfat milk at 4°C overnight with the primary antibodies GN-mAb-03 (1: 20,000) or ERVFRD-1 (1: 1,000). Blots were incubated with the HRP (horse-radish peroxidase)-conjugated secondary antibodies using goat anti-mouse antibody or goat anti-rabbit (both Thermo Fisher, 1: 5,000). The signals were detected by chemiluminescense (Bio Rad or Thermo Fisher).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA, version 5.04). Differences between sample groups were calculated by the Mann-Whitney test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of HERV Transcription Profiles in CD Patients and Healthy Controls

In a first step, we performed a RetroArray screening to establish HERV expression profiles in colonic/ileal tissue in health and inflamed as well as non-inflamed CD. Inflammatory or non-inflammatory state was defined by the endoscopic/histologic appearance and the levels of IL-8 mRNA expression normalised to β-actin in all analysed tissue samples. IL-8 mRNA expression was significantly elevated in inflamed CD samples versus healthy controls and non-inflamed CD samples (applies for all investigated ileal and colonic samples; data not shown).

The digital processed compilation of RetroArray results of colonic tissue is shown in Figure 1. Semi-quantitative densitometric analysis (for example see Fig. 3; data not shown for all HERV subgroups) and qualitative signal cut-off calculation revealed a colonic HERV core signature. One HERV group was considered to be active, if at least one subgroup was expressed in at least 5 of 6 tissue samples (per group), irrespective of disease or inflammation state. The detected core transcription pattern is composed of 5 HERV groups: HML-6, HML-8, HML-10, HERV-ERI and HERV-H (Fig. 1). No expression could be detected for groups HML-1, HML-5 and HERV-I. In addition, a variety of individually expressed HERV groups (in < 5 out of 6 samples, per sample group) like HML-3, HML-7, HERV-L and ERV9 could be found. In order to search for CD related HERV activity, we found some HERV groups exclusively expressed in non-inflamed CD like HML-9 and HERV-T. Furthermore, HML-2, HML-4, HERV-FRD, HERV-F, HERV-W and HERV-R groups are constitutively expressed in healthy controls and non-inflamed CD, but less intensive in inflamed CD (Fig. 1).

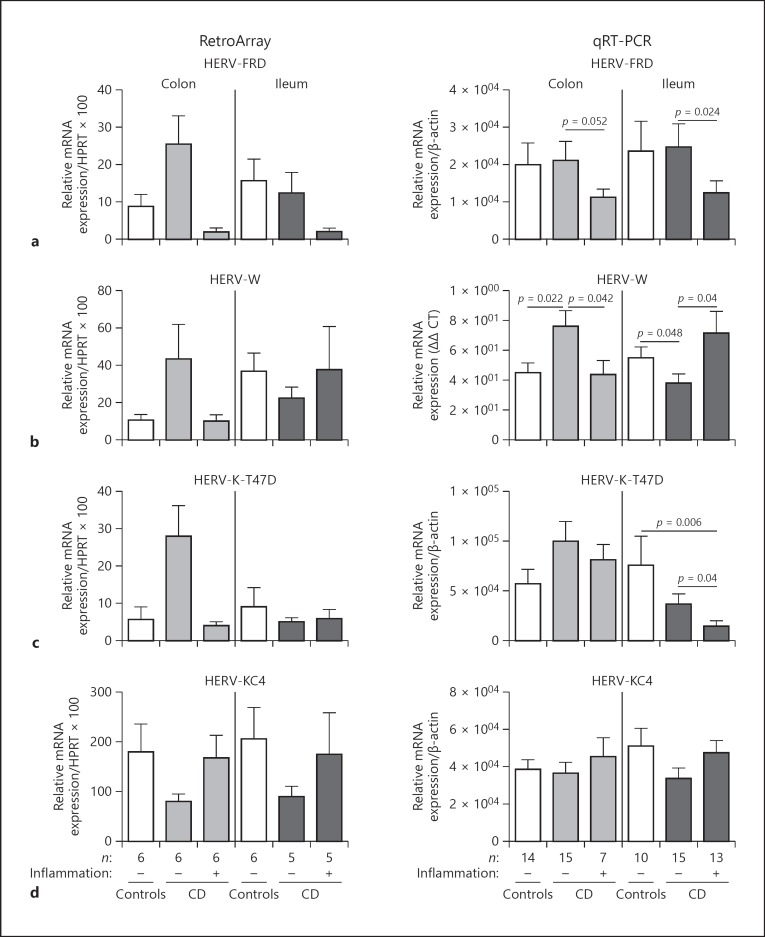

Fig. 3.

Quantification of subgroup-specific HERV transcript levels. HERV-FRD (a), HERV-W (b), HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) (c) and HERV-KC4 (HML-10) (d) subgroup sequence (mRNA) expression was analysed in controls and CD biopsies (ileum/colon) by qRT-PCR (right panel). All qRT-PCR values were normalized to β-actin levels. p values were calculated by Mann-Whitney test. A p value of < 0.05 is considered significant. On the left panel, the respective RetroArray data are depicted (normalized to HPRT). For RetroArray data no significance testing was performed because of their semi-quantitative nature.

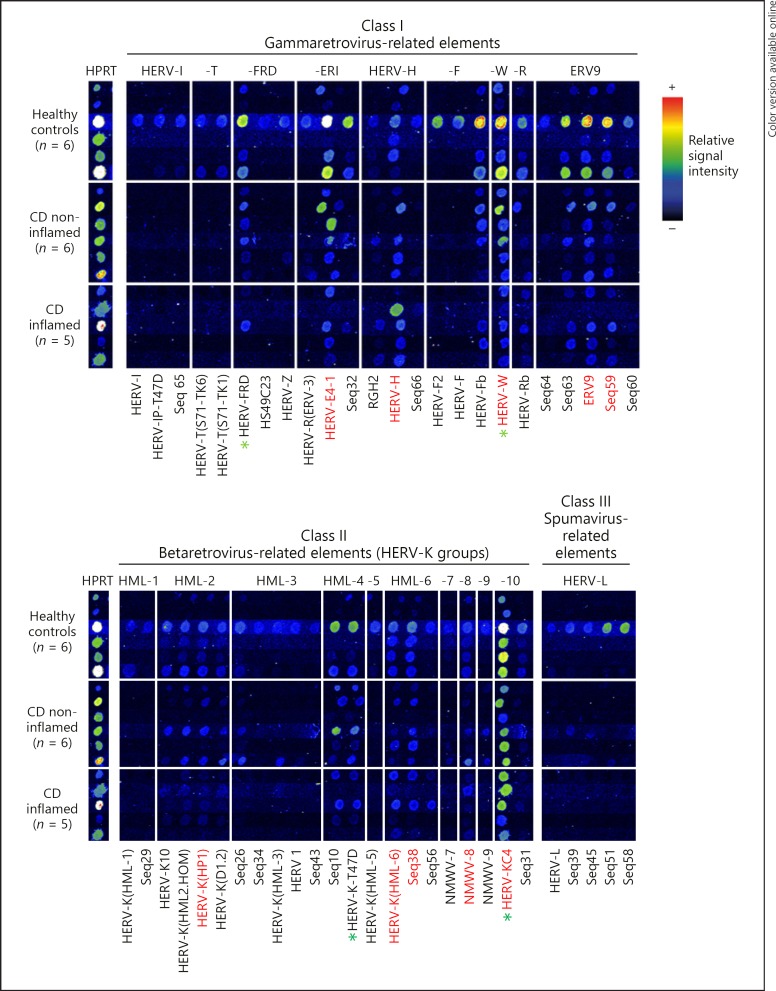

RetroArray results for ileal samples are shown in Figure 2. An ileal HERV transcription pattern (positive signals in at least 5/6 or 4/5 per sample group; irrespective of disease or inflammation state) could be detected, consisting of the HERV groups HML-2, HML-6, HML-8, HML-10, HERV-ERI, HERV-H, HERV-W, and ERV9. No significant expression could be detected for HERV group HML-7. Individually expressed HERV groups (in < 5/6 or < 4/5 samples per group) are HML-1, HML-3, HML-4, HML-5, HML-9, HERV-I, HERV-T, HERV-F, HERV-R, HERV-L. Remarkably, for the HERV group HERV-FRD, there is a constitutive expression in healthy controls and non-inflamed CD but not in inflamed CD samples (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

RetroArray analysis of HERV expression patterns in ileal tissue. Digitally aligned HERV activity patterns represent samples of 5–6 different individuals per investigated group (healthy controls; CD inflamed; CD non-inflamed). HERV subgroups defining the ileal core signature (irrespective of disease or inflammation state) are emphasized with red letters. HPRT served as housekeeping gene for internal control. Although false colour mapping was used for improved image visualization, weak signals may be unrecognizable in the figure. Core transcription pattern was therefore confirmed by densitometry (data not shown). Green asterisks highlight HERV subgroups showing the most prominent differences between healthy controls and CD (qualitatively and in densitometry [also see Fig. 3]).

These RetroArray data show that there are some differences between ileal and colonic HERV expression as well as between CD and healthy controls in the respective tissue. As the aim of our study was to investigate possible CD-specific HERV expression, we chose the most interesting candidate groups for further studies.

We identified HERV groups where the most consistent expression or the most prominent differences (qualitatively from RetroArray cut off calculation and semi-quantitatively [densitometric analysis of RetroArray]) could be found between healthy controls and CD. Densitometric subgroup analysis of HERV-FRD, HERV-W, HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) and HERV-KC4 (HML-10) revealed differences between healthy controls and CD patients (Fig. 3; further discussion see below). In a next step, qRT-PCR measurements regarding the respective HERV subgroups were performed.

Quantitative qRT-PCR Confirms Tissue-Specific Differential Expression of HERVs in CD Patients and Healthy Controls

The results of qRT-PCR measurements of HERV subgroups HERV-FRD, HERV-W, HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) and HERV-KC4 (HML-10) are shown in Figure 3. Primer, specifically binding to the pol region of selected HERVs, was chosen as described above. Additional to the samples used in the RetroArray experiments (n = 35/74), further samples were measured by qRT-PCR (n = 74/74). Accordance between RetroArray experiments and qRT-PCR experiments was all-over good, but method related not complete [30].

Transcript levels of HERV subgroup HERV-FRD were significantly decreased in inflamed ileal CD compared to non-inflamed CD (p = 0.024). In the colon, at least a comparable tendency could be observed between inflamed and non-inflamed CD (p = 0.052). No differences could be detected between healthy controls and non-inflamed CD. qRT-PCR measurements are widely in agreement with the respective RetroArray data (Fig. 3a).

HERV-W showed different expression in colonic and ileal tissue. In non-inflamed colonic CD, HERV-W was up-regulated (compared to healthy controls, p = 0.022) and down-regulated in inflamed CD (compared to non-inflamed CD, p = 0.042; Fig. 3b). In ileal tissue, we made the contrary observation. There is a significant down-regulation in non-inflamed CD compared to healthy controls (p = 0.048) and an up-regulation in inflamed ileal disease (compared to non-inflamed CD, p = 0.04). Again these data are confirmed by the respective RetroArray data (Fig. 3b).

The analysis of HERV-K-T47D revealed differences between ileal and colonic tissue too. While in non-inflamed ileal CD, HERV-K-T47D is down-regulated and even more pronounced in inflamed CD compared to controls, the colonic samples showed no significant expression disparities (Fig. 3c).

For HERV-KC4, no differences between any sample groups could be observed in the qRT-PCR measurements, even though RetroArray showed some differences (Fig. 3d). However, due to the semi-quantitative nature of RetroArray data, qRT-PCR data are more valid.

In summary, these data compiled by 2 diverse methods revealed that there are different HERV expression patterns for HERV-W, -FRD and -K-T47D in CD. These differences depend on tissue background and are related to the presence or absence of inflammation in CD.

HERV-Derived Envelope Proteins Syncytin-1 and -2 Are Expressed in the Human Gut and Down-Regulated in Acute CD Inflammation

CD is a barrier disease, where epithelial integrity is destroyed followed by several immunological perturbances [38]. As syncytin-1 and -2 are involved in placental integrity and their reduced expression has pathogenic implementations in gestation related diseases [17, 39, 40], we were interested in their expression in the healthy gut and in CD. To this end, qRT-PCR measurements for syncytin-1 and -2 were performed. We found that syncytin-1 is constitutively expressed in the human gut with mRNA (25 ng template) copy numbers about 20,000 (average healthy colon) to 50,000 (average healthy ileum; data not shown).

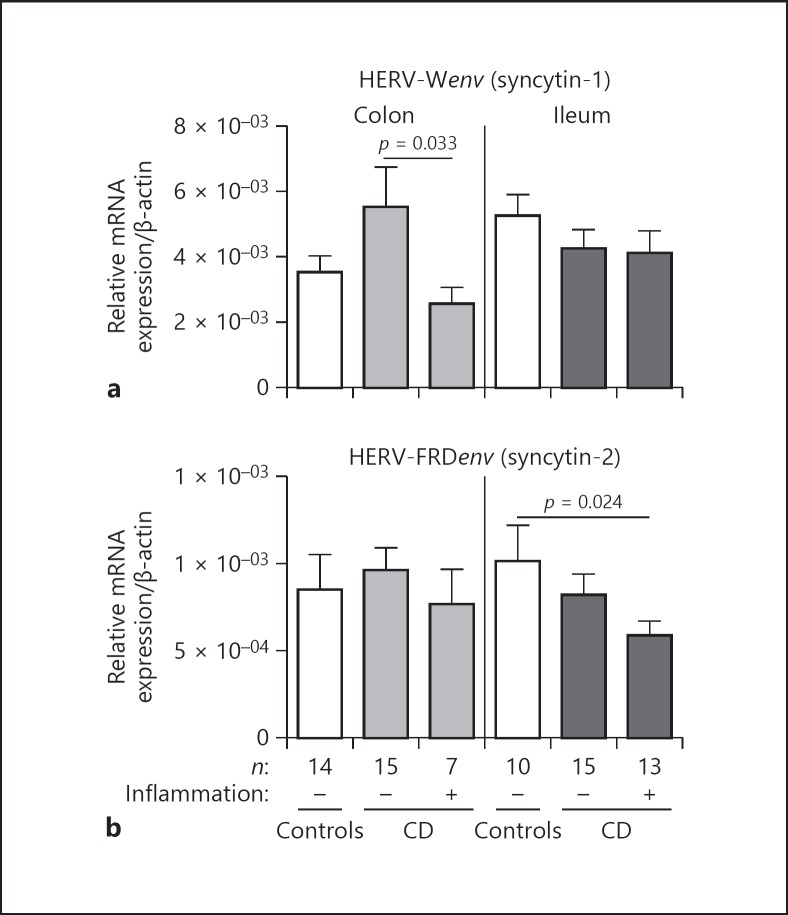

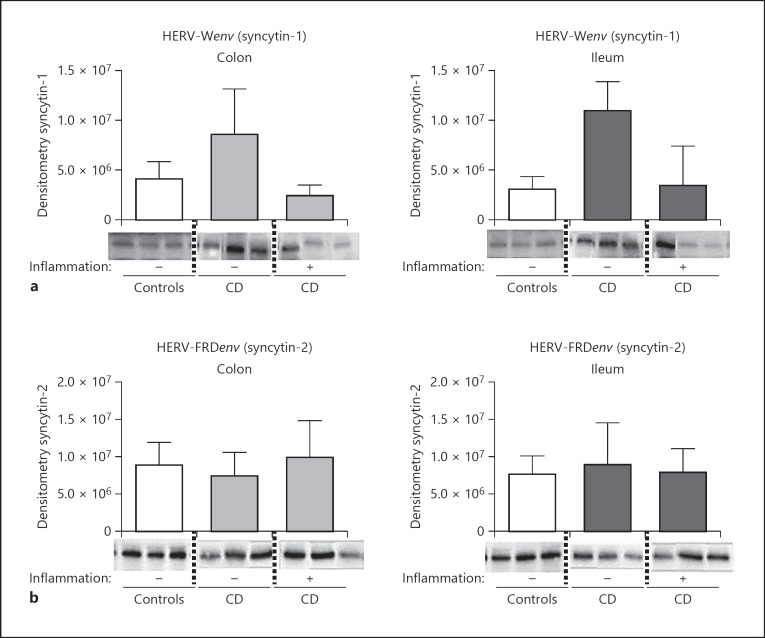

Colonic syncytin-1 expression is pronounced in non-inflamed CD compared to healthy controls, even though not statistically significant (Fig. 4a). In inflamed colonic CD, syncytin-1 is significantly down-regulated compared to non-inflamed CD (p = 0.033). No different expression patterns could be observed for ileal samples (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR transcript quantification of HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) and HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2). HERV-Wenv and HERV-FRDenv mRNA expression was analyzed in controls and CD (ileum/colon) by qRT-PCR (normalized to β-actin). p values were calculated by Mann-Whitney test. A p value of < 0.05 is considered significant. (a) HERV-Wenv transcripts are significantly decreased in inflamed vs. non-inflamed colonic CD, an effect not seen in the ileal mucosa. (b) HERV-FRDenv mRNA is significantly down-regulated in inflamed ileal CD compared to controls. In the colonic tissue, no differences could be detected.

Also, syncytin-2 is constitutively expressed in the human gut with mRNA (25 ng template) copy numbers about 6,000 (average healthy colon) to 8,000 (average healthy ileum; data not shown). The results of syncytin-2 mRNA measurements are depicted in Figure 4b. Between colonic sample groups, no differences could be detected. However, in the ileum, there is a significant diminished expression of syncytin-2 in inflamed CD (p = 0.024). Again, this gives a hint for a loss of possible functions of HERV-derived proteins during CD inflammation.

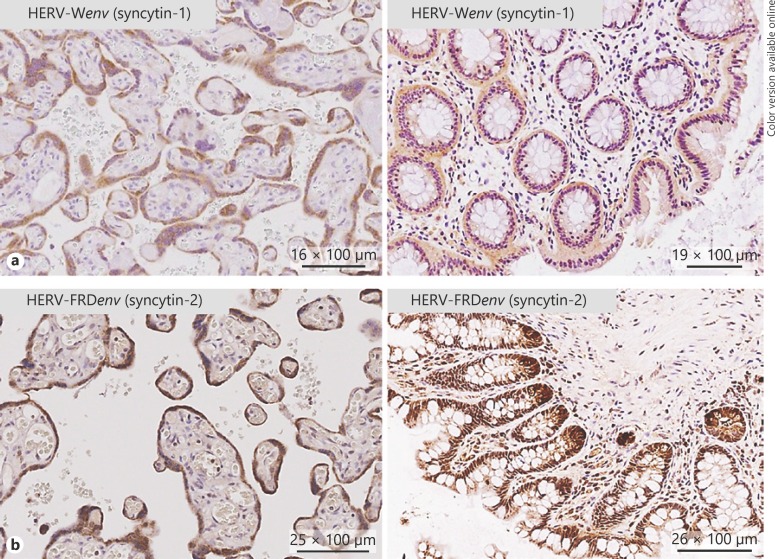

As syncytin-1 and -2 transcripts are expressed in the human gut, we next investigated the expression of the encoded proteins by IHC. Five biopsies per sample group (as sample groups above) were investigated. Placental tissue deserved as positive/negative control and showed specific antibody binding. IHC revealed the expression of syncytin-1 and -2 in the epithelium of all ileal and colonic samples studied (Fig. 5). Furthermore, in some samples, a pronounced expression could be found at the ileal and colonic crypt base, especially for syncytin-2. No significant differences could be observed between any sample groups. Investigating syncytin-1 and -2 protein expression by WB, we could confirm a stable expression of both proteins in ileal and colonic biopsies (Fig. 6a, b). In inflamed tissue, individual specimens showed diminished expression especially of syncytin-1.

Fig. 5.

HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) and HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) are expressed in the gut epithelium (IHC). a On the right panel, a representative colonic tissue (CD patient in remission) staining for syncytin-1 is depicted. A consistent positive staining can be found in the epithelium. On the left panel, human placental tissue is depicted (positive control). Syncytin-1 is expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast cell layer. b Right panel: representative staining of a healthy human ileal tissue specimen with an antibody against syncytin-2. Consistent staining can be found in the epithelial cell layer, with accentuation on the crypt basis. Left panel: human placental tissue deserved as positive control with specific staining of the syncytiotrophoblast cell layer.

Fig. 6.

HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) and HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) proteins are expressed in the gut epithelium (WB). a On the upper panel, 3 (out of 5) representative Western Blot results (60 kDa) including semiquantitative densitometric analysis (bars; n = 5) for syncytin-1 are depicted (colonic and ileal tissue specimens of different CD patients and healthy controls). A consistent positive syncytin-1 expression can be found, with diminished expression in specimens of inflamed CD. b Three (out of 5) representative WB results including semiquantitative densitometric analysis (bars; n = 5) for syncytin-2 are depicted (colonic and ileal tissue of different CD patients and healthy controls). A consistent positive syncytin-2 expression can be found.

Discussion

Characterization of HERV Expression Profiles in CD and the Healthy Gut

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating HERV expression in CD and the healthy gut using a comprehensive RetroArray. However, there are data in the literature, for example, derived from metagenomic analysis of the virome in colonic IBD biopsies, showing differences in the microbiome, virome and HERV expression. Most interestingly, in patients with herpesviridae in the colon, there is an increased expression of HERVs connected with differences in the diversity of the microbiome [41]. In these lines, Norman et al. [42], also found disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome of IBD patients and most importantly, these changes were not secondary to changes in the microbiome, supporting the hypothesis that changes in the virome may contribute to intestinal inflammation and bacterial dysbiosis.

With our approach, we were able to detect an HERV expression pattern for colonic and ileal tissue, showing HERV groups HML-6, HML-8, HML-10, HERV-ERI and HERV-H being constitutively expressed in both tissues, whereas HML-2, HERV-W and ERV9 are constitutively expressed in ileal tissue but not in the colon. This is in line with the fact that HERV elements are expressed in a tissue-specific manner [30, 33, 43, 44]. In addition to this expression pattern, we identified several HERVs being active with an inter-individual variability, differences attributed to an individual epigenetic background regarding HERV expression [33, 43, 44, 45]. Since CD is a trans-mural gut tissue overarching disease [46], HERV expression screening was obtained by studying tissue biopsies. Certainly, as a consequence of this approach, no statement with respect to the cell type expressing HERVs is possible with our data.

We were able to identify several HERV groups with differential expression in CD versus healthy controls, namely, HERV-T, HML-2, HML-4, HML-9, HERV-FRD, HERV-F, HERV-W and HERV-R for colonic tissue and, for example, HERV-FRD for ileal tissue. For at least 3 HERV subgroups (HERV-FRD, HERV-W and HERV-K-T47D [HML-4]) these differences could be confirmed by qRT-PCR.

Different regulation of HERV expression has been associated with many inflammatory diseases like systemic lupus erythematosis, rheumatoid arthritis and so on [47, 48, 49, 50, 51]. However, it is questionable if HERVs are only harmless bystanders or core elements of the respective diseases. But nevertheless, it is assumable that they contribute to the course of diseases [51].

HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) LTRs, for example, are dispersed over the whole human genome [52]. In our study, HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) showed a down-regulation in acute CD of the ileum. HERV-K-T47D (HML-4) LTRs have been shown to modulate the expression of experimental reporter genes and exert biological function by mediating polyadenylation of cellular sequences [53, 54]. Therefore, the diminished expression of these elements in CD associated ileal inflammation might modulate gene expression in CD.

HERV-W and -FRD Groups Are Differentially Expressed in CD versus the Healthy Gut: Loss of Immune-Modulatory Properties of Syncytin-1 and -2 in Inflamed CD

One of the main findings of our study is the differential expression of HERV groups HERV-FRD and HERV-W in a tissue-specific manner. Both HERV groups are encoding for envelope proteins named HERV-FRDenv (syncytin-2) and HERV-Wenv (syncytin-1) with a well-known immune modulatory function [17, 18, 19, 20]. In our study, the HERV-FRD group, for example, is significantly less expressed in inflamed ileal CD and with the same tendency in inflamed colonic CD, corresponding with the respective expression data of syncytin-2. Also syncytin-1 is significantly less expressed in acute CD of the colon compared to non-inflamed colonic CD.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating perpetuated expression of syncytin-1 and -2 in diseased ileal and colonic tissue. Based on these mRNA expression data, we additionally detected expression of these HERV-derived proteins in ileal and colonic epithelial cells by IHC and WB analysis.

Based on the available literature, there are 2 hypotheses on how syncytin-1 and -2 might influence the phenotypic appearance of CD. As already outlined, both proteins are involved in the fusion of placental syncytiotrophoblast cell layer as core element of placental surface integrity [16]. Maybe these proteins perform similar functions in the gut in terms of regulation of tissue integrity in health and inflammation, a function not investigated so far. In these lines, the fusogenic properties of HERV proteins are not exclusively restricted to placental tissue context. They are also involved in osteoclast fusions in bone tissue and breast cancer-endothelial cell fusions [55, 56]. Furthermore, both proteins possess an ISD that modulates inflammatory processes [17, 18, 19, 20]. Cianciolo et al. [20] showed that an octadecapeptide derived from the ISD can inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines and induces the expression of anti-inflammatory IL-10 in a murine model of peritonitis. Most recently, Tolstrup et al. [19] performed a similar study, investigating the effects of a synthetic retroviral ISD peptide in 2 murine skin inflammation models. Topical application of cream containing this ISD peptide resulted in a reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha and IL-6. One can imagine that the loss of this immune-modulatory activity of HERV-derived ISD peptides in inflammation might modulate active CD.

Summary and Conclusions

With this study we established a distinct HERV expression profile of healthy colonic and ileal tissue (RetroArray) and identified differential expression of several HERV groups in CD. Selected HERV groups were studied by qRT-PCR and revealed tissue-specific perturbation of HERV-W, HERV-FRD and HERV-K-T47D (HML-4).

Most prominently, this is the first report quantitatively characterizing HERV-Wenv and HERV-FRDenv mRNA expression in the gut, with tissue-specific diminished expression in inflamed CD. This might result in the loss of their immune-modulatory function (ISD-related function), possibly influencing the phenotypic appearance of CD.

Disclosure Statement

All authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Funding Source

The whole work was supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation (T.K.), Stuttgart, Germany, and by the European Research Council. J.W. is a European Starting grantee.

Author Contributions

(1) Study concept and design; (2) acquisition of data; (3) analysis and interpretation of data; (4) drafting of the manuscript; (5) critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; (6) statistical analysis; (7) obtained funding; (8) technical, or material support; (9) study supervision. T.K.: 1–7; L.C.: 2, 3, 5; M.J.O.: 2, 3, 5; G.O.: 2, 3; E.F.S.: 1, 3–5, 9; N.P.M.: 5, 8, 9; W.S.: 1–9; J.W.: 1, 3–5, 7–9. All authors approved of the final draft submitted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jutta Bader, Marion Strauss (Tübingen, Germany) and Helga Kleiner (Mannheim, Germany) for expert technical assistance. We are also grateful to Dr. Hervé Perron (GeNeuro, Geneva, Switzerland), who generously provided the GN-mAb_03 anti-HERV-Wenv antibody for the IHC/WB-based studies.

verified

References

- 1.Voisset C, Weiss RA, Griffiths DJ. Human RNA “rumor” viruses: the search for novel human retroviruses in chronic disease. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008 Mar;72((1)):157–96. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00033-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li WH, Gu Z, Wang H, Nekrutenko A. Evolutionary analyses of the human genome. Nature. 2001 Feb;409((6822)):847–9. doi: 10.1038/35057039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belshaw R, Katzourakis A, Paces J, Burt A, Tristem M. High copy number in human endogenous retrovirus families is associated with copying mechanisms in addition to reinfection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005 Apr;22((4)):814–7. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belshaw R, Pereira V, Katzourakis A, Talbot G, Paces J, Burt A, et al. Long-term reinfection of the human genome by endogenous retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004 Apr;101((14)):4894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307800101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths DJ. Endogenous retroviruses in the human genome sequence. Genome Biol. 2001;2((6)):S1017. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mager D, Medstrand P., Retroviral repeat sequences . Editied by Cooper D. London, United Kingdom: Nature Publishing group; 2003. Nature encyclopedia of the human genome; pp. P. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee YN, Bieniasz PD. Reconstitution of an infectious human endogenous retrovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2007 Jan;3((1)):e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isbel L, Whitelaw E. Endogenous retroviruses in mammals: an emerging picture of how ERVs modify expression of adjacent genes. BioEssays. 2012 Sep;34((9)):734–8. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solyom S, Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements in the human genome: implications for disease. Genome Med. 2012 Feb;4((2)):12. doi: 10.1186/gm311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamprecht B, Walter K, Kreher S, Kumar R, Hummel M, Lenze D, et al. Derepression of an endogenous long terminal repeat activates the CSF1R proto-oncogene in human lymphoma. Nat Med. 2010 May;16((5)):571–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebollo R, Romanish MT, Mager DL. Transposable elements: an abundant and natural source of regulatory sequences for host genes. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46((1)):21–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan IK, Rogozin IB, Glazko GV, Koonin EV. Origin of a substantial fraction of human regulatory sequences from transposable elements. Trends Genet. 2003 Feb;19((2)):68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitelaw E, Martin DI. Retrotransposons as epigenetic mediators of phenotypic variation in mammals. Nat Genet. 2001 Apr;27((4)):361–5. doi: 10.1038/86850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson PN, Hooley P, Roden D, Davari Ejtehadi H, Rylance P, Warren P, et al. Molecular Immunology Research Group Human endogenous retroviruses: transposable elements with potential? Clin Exp Immunol. 2004 Oct;138((1)):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balada E, Ordi-Ros J, Vilardell-Tarrés M. Molecular mechanisms mediated by human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) in autoimmunity. Rev Med Virol. 2009 Sep;19((5)):273–86. doi: 10.1002/rmv.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupressoir A, Lavialle C, Heidmann T. From ancestral infectious retroviruses to bona fide cellular genes: role of the captured syncytins in placentation. Placenta. 2012 Sep;33((9)):663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangeney M, Renard M, Schlecht-Louf G, Bouallaga I, Heidmann O, Letzelter C, et al. Placental syncytins: genetic disjunction between the fusogenic and immunosuppressive activity of retroviral envelope proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 Dec;104((51)):20534–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707873105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haraguchi S, Good RA, Cianciolo GJ, Day NK. A synthetic peptide homologous to retroviral envelope protein down-regulates TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma mRNA expression. J Leukoc Biol. 1992 Oct;52((4)):469–72. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolstrup M, Johansen C, Toft L, Pedersen FS, Funding A, Bahrami S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of a retrovirus-derived immunosuppressive peptide in mouse models. BMC Immunol. 2013 Nov;14((1)):51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-14-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cianciolo GJ, Pizzo SV. Anti-inflammatory and vasoprotective activity of a retroviral-derived peptide, homologous to human endogenous retroviruses: endothelial cell effects. PLoS One. 2012;7((12)):e52693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vargas A, Toufaily C, LeBellego F, Rassart É, Lafond J, Barbeau B. Reduced expression of both syncytin 1 and syncytin 2 correlates with severity of preeclampsia. Reprod Sci. 2011 Nov;18((11)):1085–91. doi: 10.1177/1933719111404608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabriel U, Steidler A, Trojan L, Michel MS, Seifarth W, Fabarius A. Smoking increases transcription of human endogenous retroviruses in a newly established in vitro cell model and in normal urothelium. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 Aug;26((8)):883–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manghera M, Douville RN. Endogenous retrovirus-K promoter: a landing strip for inflammatory transcription factors? Retrovirology. 2013 Feb;10((1)):16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank O, Jones-Brando L, Leib-Mosch C, Yolken R, Seifarth W. Altered transcriptional activity of human endogenous retroviruses in neuroepithelial cells after infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Infect Dis. 2006 Nov;194((10)):1447–9. doi: 10.1086/508496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutkowski N, Conrad B, Thorley-Lawson DA, Huber BT. Epstein-Barr virus transactivates the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K18 that encodes a superantigen. Immunity. 2001 Oct;15((4)):579–89. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tai AK, Luka J, Ablashi D, Huber BT. HHV-6A infection induces expression of HERV-K18-encoded superantigen. J Clin Virol. 2009 Sep;46((1)):47–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assinger A, Yaiw KC, Göttesdorfer I, Leib-Mösch C, Söderberg-Nauclér C. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) induces human endogenous retrovirus (HERV) transcription. Retrovirology. 2013 Nov;10((1)):132. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klag T, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Defective antibacterial barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2013;31((3-4)):310–6. doi: 10.1159/000354858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostaff MJ, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Antimicrobial peptides and gut microbiota in homeostasis and pathology. EMBO Mol Med. 2013 Oct;5((10)):1465–83. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seifarth W, Frank O, Zeilfelder U, Spiess B, Greenwood AD, Hehlmann R, et al. Comprehensive analysis of human endogenous retrovirus transcriptional activity in human tissues with a retrovirus-specific microarray. J Virol. 2005 Jan;79((1)):341–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.341-352.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seifarth W, Spiess B, Zeilfelder U, Speth C, Hehlmann R, Leib-Mösch C. Assessment of retroviral activity using a universal retrovirus chip. J Virol Methods. 2003 Sep;112((1-2)):79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(03)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, Allez M, et al. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohn's Colitis. 2010 Feb;4((1)):7–27. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank O, Giehl M, Zheng C, Hehlmann R, Leib-Mösch C, Seifarth W. Human endogenous retrovirus expression profiles in samples from brains of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. J Virol. 2005 Sep;79((17)):10890–901. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.10890-10901.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifarth W, Frank O, Schreml J, Leib-Mösch C. Encyclopedia of DNA Research. Hauppauge (NY): Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2011. RetroArray - a comprehensive diagnostic DNA chip for rapid detection and identification of retroviruses, retroviral contaminants and mistaken identity of cell lines. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Parseval N, Lazar V, Casella JF, Benit L, Heidmann T. Survey of human genes of retroviral origin: identification and transcriptome of the genes with coding capacity for complete envelope proteins. J Virol. 2003 Oct;77((19)):10414–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10414-10422.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaeger SU, Schroeder BO, Meyer-Hoffert U, Courth L, Fehr SN, Gersemann M, et al. Cell-mediated reduction of human β-defensin 1: a major role for mucosal thioredoxin. Mucosal Immunol. 2013 Nov;6((6)):1179–90. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25((4)):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009 Nov;361((21)):2066–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knerr I, Huppertz B, Weigel C, Dötsch J, Wich C, Schild RL, et al. Endogenous retroviral syncytin: compilation of experimental research on syncytin and its possible role in normal and disturbed human placentogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004 Aug;10((8)):581–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frendo JL, Olivier D, Cheynet V, Blond JL, Bouton O, Vidaud M, et al. Direct involvement of HERV-W Env glycoprotein in human trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 May;23((10)):3566–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3566-3574.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Jovel J, Halloran B, Wine E, Patterson J, Ford G, et al. Metagenomic analysis of microbiome in colon tissue from subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases reveals interplay of viruses and bacteria. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Jun;21((6)):1419–27. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, Droit L, Liu CY, Keller BC, et al. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2015 Jan;160((3)):447–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank O, Verbeke C, Schwarz N, Mayer J, Fabarius A, Hehlmann R, et al. Variable transcriptional activity of endogenous retroviruses in human breast cancer. J Virol. 2008 Feb;82((4)):1808–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02115-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haupt S, Tisdale M, Vincendeau M, Clements MA, Gauthier DT, Lance R, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus transcription profiles of the kidney and kidney-derived cell lines. J Gen Virol. 2011 Oct;92((Pt 10)):2356–66. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gosenca D, Gabriel U, Steidler A, Mayer J, Diem O, Erben P, et al. HERV-E-mediated modulation of PLA2G4A transcription in urothelial carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7((11)):e49341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan;20((1)):91–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tugnet N, Rylance P, Roden D, Trela M, Nelson P. Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVs) and Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease: Is There a Link? Open Rheumatol J. 2013 Mar;7:13–21. doi: 10.2174/1874312901307010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Douville R, Liu J, Rothstein J, Nath A. Identification of active loci of a human endogenous retrovirus in neurons of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011 Jan;69((1)):141–51. doi: 10.1002/ana.22149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perron H, Lang A. The human endogenous retrovirus link between genes and environment in multiple sclerosis and in multifactorial diseases associating neuroinflammation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010 Aug;39((1)):51–61. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryan FP. An alternative approach to medical genetics based on modern evolutionary biology. Part 3: HERVs in diseases. J R Soc Med. 2009 Oct;102((10)):415–24. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Portis JL. Perspectives on the role of endogenous human retroviruses in autoimmune diseases. Virology. 2002 Apr;296((1)):1–5. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seifarth W, Baust C, Murr A, Skladny H, Krieg-Schneider F, Blusch J, et al. Proviral structure, chromosomal location, and expression of HERV-K-T47D, a novel human endogenous retrovirus derived from T47D particles. J Virol. 1998 Oct;72((10)):8384–91. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8384-8391.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baust C, Seifarth W, Schön U, Hehlmann R, Leib-Mösch C. Functional activity of HERV-K-T47D-related long terminal repeats. Virology. 2001 May;283((2)):262–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baust C, Seifarth W, Germaier H, Hehlmann R, Leib-Mösch C. HERV-K-T47D-Related long terminal repeats mediate polyadenylation of cellular transcripts. Genomics. 2000 May;66((1)):98–103. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Søe K, Andersen TL, Hobolt-Pedersen AS, Bjerregaard B, Larsson LI, Delaissé JM. Involvement of human endogenous retroviral syncytin-1 in human osteoclast fusion. Bone. 2011 Apr;48((4)):837–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bjerregaard B, Holck S, Christensen IJ, Larsson LI. Syncytin is involved in breast cancer-endothelial cell fusions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006 Aug;63((16)):1906–11. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6201-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]