Abstract

Background

Absence of interlobar collateral ventilation using the Chartis measurement is the key predictor for successful endobronchial valve treatment in severe emphysema. Chartis was originally validated in spontaneous breathing patients under conscious sedation (CS); however, this can be challenging due to cough, mucus secretion, mucosal swelling, and bronchoconstriction. Performing Chartis under general anesthesia (GA) avoids these problems and may result in an easier procedure with a higher success rate. However, using Chartis under GA with positive pressure ventilation has not been validated.

Objectives

In this study we investigated the impact of anesthesia technique, CS versus GA, on the feasibility and outcomes of Chartis measurement.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed all Chartis measurements performed at our hospital from October 2010 until December 2017.

Results

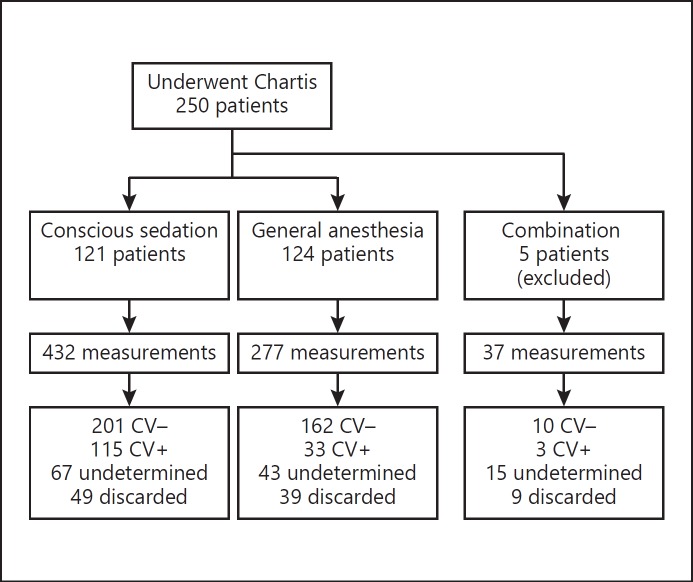

We analyzed 250 emphysema patients (median forced expiratory volume in 1 s 26%, range 12–52% predicted). In 121 patients (48%) the measurement was performed using CS, in 124 (50%) using GA, and in 5 (2%) both anesthesia techniques were used. In total, 746 Chartis readings were analyzed (432 CS, 277 GA, and 37 combination). Testing under CS took significantly longer than GA (median 19 min [range 5—65] vs. 11 min [3–35], p < 0.001) and required more measurements (3 [1–13] vs. 2 [1–6], p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in target lobe volume reduction after treatment (-1,123 mL [–3,604 to 332] in CS vs. −1,251 mL [-3,333 to −1] in GA, p = 0.35).

Conclusions

In conclusion, Chartis measurement under CS took significantly longer and required more measurements than under GA, without a difference in treatment outcome. We recommend a prospective trial comparing both techniques within the same patients to validate this approach.

Key Words: Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction, Chartis measurement, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Collateral ventilation, Conscious sedation, General anesthesia

Introduction

Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction using endobronchial one-way valves (EBV) has been shown to be clinically effective and to have an acceptable safety profile in selected patients with severe emphysema [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Maximal clinical improvement after EBV treatment is associated with complete lobar atelectasis [1, 2, 6, 7, 8]. However, lobar atelectasis will not be achieved in the presence of interlobar collateral ventilation due to an incomplete interlobar fissure. In approximately 60% of the patients with severe emphysema, the interlobar fissure is not complete [9]. Interlobar collateral ventilation can be measured using the Chartis System® (Pulmonx Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA).

The Chartis system was originally validated in patients using conscious sedation [8, 10]. However, in clinical practice the Chartis measurement is also often performed using general anesthesia for practical reasons. Under conscious sedation, measurements are often challenging to perform or even fail, due to increased coughing, mucus secretion, bronchoconstriction, swelling of mucosa, and difficulty to maintain an optimal level of sedation. Therefore, general anesthesia was recently suggested to be the preferred and recommended technique for both the Chartis measurement and the subsequent EBV placement due to the ease of airway and patient management [11].

To our knowledge, effects of conscious sedation and general anesthesia on the Chartis measurement have never been compared in the literature. The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of anesthesia technique, conscious sedation versus general anesthesia, on both the feasibility of the Chartis measurement and the outcome of subsequent EBV placement.

Methods

Study Design and Population

Retrospectively, we analyzed data of all patients who underwent a Chartis measurement at the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. From October 2010 until December 2017, we performed Chartis measurements in 250 patients in different trials (“Chartis trial” [8], “STELVIO trial” [1], “IMPACT trial” [4], “TRANSFORM trial” [5], “BREATHE-NL registry” [NCT02815683]) and in patients treated in a compassionate use setting (Table 1). All trials had prior approval from the local ethics committee and all patients provided informed consent.

Table 1.

Patients per anesthesia technique per study

| Conscious sedation | General anesthesia | Combination | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chartis [8], 2013 | 29 (24) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| STELVIO [1], 2015 | 80 (66) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) |

| IMPACT [4], 2016 | 5 (4) | 20 (16) | 1 (20) |

| TRANSFORM [5], 2017 | 0 (0) | 15 (12) | 0 |

| BREATHE-NL | 0 (0) | 75 (60) | 0 |

| Compassionate use | 7 (6) | 13 (11) | 0 |

| Total | 121 (100) | 124 (100) | 5 (100) |

Data is presented as number of cases (percentage of total cases).

Anesthesia Technique

Conscious sedation is a drug-induced state of reduced consciousness during which patients are able to purposefully respond to verbal commands or light tactile stimuli and are able to maintain oxygenation and airway control without intervention [12]. Conscious sedation was induced with intravenous propofol and remifentanil. Medication dosage was titrated up to a level where patients were adequately sedated but still arousable and breathing spontaneously. In addition, a 1% w/v lidocaine spray was applied locally to the upper and lower airways.

General anesthesia is a drug-induced loss of consciousness during which patients are not arousable, even by painful stimulation, spontaneous ventilation cannot be maintained, and an artificial maintenance of open airway is necessary [12]. General anesthesia was induced through administration of intravenous propofol and remifentanil and muscle relaxation was achieved with rocuronium bromide. Patients were intubated with a flexible 9-mm endotracheal tube and positive pressure ventilation was applied with target settings of low ventilation frequency (8–10×/min), long expiratory settings (inspiratory/expiratory ratio of 1: 3), and positive end-expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O [11].

Chartis Measurement

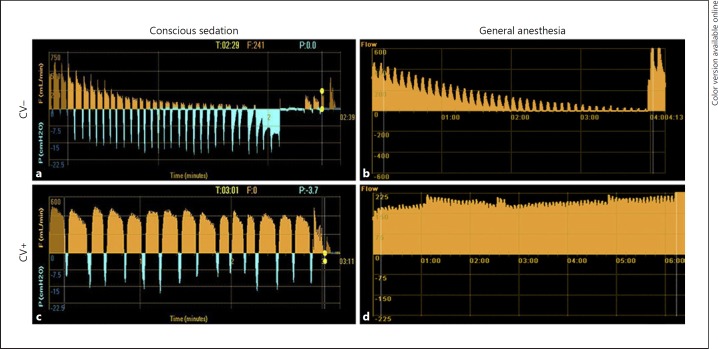

Collateral ventilation measurements were performed using the Chartis System® (Pulmonx Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA). The Chartis system consists of a catheter, with an inflatable balloon at the tip, which can be advanced through the 2.8-mm or larger working channel of a bronchoscope (Fig. 1). Inflation of the balloon allows for temporary occlusion of the airway, during which airflow coming from the occluded lobe can be assessed [13]. Expired airflow volume, pressure, and resistance measurements are analyzed and visualized by the Chartis console. Distinctive airflow patterns allow for assessment of collateral ventilation status (Fig. 2) [9].

Fig. 1.

Chartis system® (Pulmonx Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA). a Console with catheter. b Catheter with inflated balloon at tip. c Bronchoscopic view of inflated balloon at catheter tip in airway. d Bronchoscopic view through inflated balloon at catheter tip in airway.

Fig. 2.

Chartis measurement reports for the 4 different categories. a Negative collateral ventilation (CV) under conscious sedation. b Negative CV under general anesthesia. c Positive CV under conscious sedation. d Positive CV under general anesthesia.

Outcome Variables

We analyzed the Chartis measurements that were performed in the predetermined treatment target and ipsilateral lobes. Our primary outcome was the total duration of Chartis measurement, defined as the total duration of all measurement attempts combined. Secondary outcomes were the number of Chartis measurements performed per patient, number of measurements per lobe, number of lobes measured, expired airflow volume measured with Chartis, target lobe volume reduction (TLVR) after treatment, and Chartis outcome category. The Chartis outcome was categorized by the treating physician in 4 different categories: (1) negative collateral ventilation, (2) positive collateral ventilation, (3) undetermined measurement (signal output but not possible to determine collateral ventilation status, caused for example by touching of the bronchial wall by the Chartis catheter tip, secretion occlusion of the catheter leading to low/no flow, or measurement distortion by coughing and patient exhaling during exertion), and (4) discarded measurement (not possible to obtain valid signal output due to loss of balloon seal and total catheter blockage due to excessive mucus).

TLVR was calculated using different quantitative high-resolution computed tomography software per study protocol. Scans were analyzed using Thirona LungQ (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) (STELVIO, BREATHE-NL registry, and compassionate use), VIDA Diagnostics software (Coralville, IA, USA) (TRANSFORM and IMPACT), or MedQia software (Los Angeles, CA, USA) (CHARTIS).

Statistical Analysis

To compare differences in patient characteristics, measurements duration, number of Chartis measurements, number of measurements per lobe, number of lobes measured, expired airflow volume, and TLVR between conscious sedation and general anesthesia, an independent-samples t test was performed in case of normal distribution of data and a Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-normal distribution. p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, New York, NY, USA).

Results

Of the 250 included patients, 121 patients (48%) underwent conscious sedation and 124 patients (50%) underwent general anesthesia. Five patients (2%) received both anesthesia techniques after conversion from conscious sedation to general anesthesia; these were not used in the analyses (see Fig. 3 for patient flowchart; patient characteristics are shown in Table 2). No direct anesthesia-related complications were observed in either group.

Fig. 3.

Patient flowchart. Patients who received both conscious sedation and general anesthesia were not included in the analysis. CV–, negative collateral ventilation; CV+, positive collateral ventilation.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | Conscious sedation | General anesthesia | Combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 121 | 124 | 5 |

| Female/male, % | 60/40 | 68/32 | 80/20 |

| Age, years | 60 (36–78) | 62 (42–78) | 54 (47–68) |

| BMI | 23.8 (17–37) | 23.2 (16–35) | 22.6 (20–26) |

| Pack-years, years* | 35 (0–110) | 39 (8–148) | 35 (18–60) |

| FEV1, % predicted* | 27.0 (12–52) | 25.8 (12–48) | 26.0 (23–32) |

| RV, % predicted* | 216.0 (120–361) | 232.5 (130–484) | 245.0 (182–263) |

| 6MWD, m* | 361.3±95.4 | 316.6±100.3 | 411.8±72.7 |

| SGRQ total score, units | 60.3±12.8 | 60.0±11.3 | 56.1±8.1 |

| Target lobe volume, mL | 1,747 (780–4,666) | 1,632 (956–3,755) | 2,146 (1,067–2,746) |

Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation in case of normal distribution of data and as median (range) in case of non-normal distribution. BMI, Body mass index; FEV, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; RV, residual volume; 6MWD, 6-minute walking distance; SGRQ, St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Difference between conscious sedation and general anesthesia was analyzed with an independent-samples t test in case of normal distribution of data and a Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-normal distribution.

p < 0.05 between conscious sedation and general anesthesia.

The Chartis measurement outcomes per anesthesia technique are provided in Table 3. Chartis measurement under conscious sedation took significantly (p < 0.001) longer than under general anesthesia (median 19 min [range 5–65] vs. 11 min [3–35]), required a significantly (p < 0.001) higher number of measurements (3 [1–13] vs. 2 [1–6]), and required a significantly (p < 0.001) higher number of measurements per lobe (2 [1–7] vs. 1 [1–3]). The proportions of undetermined and discarded measurements and the number of lobes measured per patient were not significantly different between the groups (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Chartis measurement outcomes under conscious sedation and general anesthesia

| Conscious sedation | General anesthesia | Median difference | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement length | ||||

| Duration of total Chartis procedure per patient, s | –1,140 (300 to 3,900) | 656 (180 to 2,100) | 484 | <0.001 |

| Sum of measurement duration per patient, excluding discarded measurements, s | 668 (103 to 2,109) | 398 (61 to 1,211) | 270 | <0.001 |

| Sum of measurement duration per patient, in measurements with CV-negative outcome, s | 356 (95 to 1,469) | 308 (65 to 875) | 48 | 0.02 |

| Number of measurements | ||||

| Number of measurements per patient | 3 (1 to 13) | 2 (1 to 6) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Number of measurements per patient, excluding discarded and undetermined measurements | 2 (0 to 13) | 1 (0 to 4) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Number of discarded measurements, total number in group (percentage of total measurements) | 49 (11%) | 39 (14%) | NA | 0.97 |

| Number of undetermined measurements, total number in group (percentage of total measurements) | 67 (16%) | 43 (16%) | NA | 0.22 |

| Measurements per lobe, including discarded and undetermined measurements | 2 (1 to 7) | 1 (1 to 3) | 1 | <0.001 |

| Measured lobes per patient, including discarded and undetermined measurements | 2 (1 to 4) | 2 (1 to 4) | 0 | 0.32 |

| Analyzed airflow volume | ||||

| Expired airflow volume per patient, mL | 903 (19 to 6,719) | 462 (34 to 7,639) | 441 | <0.001 |

| Expired airflow volume per patient in measurements with CV-negative outcome, mL | 490 (6 to 2,504) | 390 (34 to 1,561) | 100 | 0.015 |

| Target lobe volume reduction | ||||

| Target lobe volume reduction per patient, mL | –1,123 (–3,604 to 332) | –1,251 (–3,333 to –1) | 128 | 0.35 |

| Target lobe volume reduction per patient, % | 72 (100 to 24) | 77 (100 to 0) | 5 | 0.27 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation in case of normal distribution of data and as median (range) in case of non-normal distribution. In case of categorical variables, data is presented as n (%). Difference between conscious sedation and general anesthesia was analyzed with an independent-samples t test in case of normal distribution of data and a Mann-Whitney U test in case of non-normal distribution. CV, collateral ventilation.

Median TLVR in the conscious sedation group was −1,123 mL (–3,604 to 332) (relative TLVR 72%) compared to −1,251 mL (–3,333 to −1) (relative TLVR 77%) in the general anesthesia group. Differences in both absolute as well as relative TLVR were not significant between anesthesia techniques.

In total, 746 Chartis measurements (432 conscious sedation, 277 general anesthesia, and 37 combination) were performed in the predetermined target or ipsilateral lobes, of which 373 were categorized as negative collateral ventilation, 151 positive collateral ventilation, 125 were undetermined, and 97 were discarded measurements. Under conscious sedation, the Chartis catheter balloon ruptured 3 times compared to once under general anesthesia.

In patients with absence of collateral ventilation, the expired airflow volume was significantly (p = 0.015) higher under conscious sedation than under general anesthesia (490 mL [range: 6–2,504] vs. 390 mL [range: 34–1,561]).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing conscious sedation and general anesthesia during bronchoscopic evaluation of interlobar collateral ventilation with Chartis in patients with severe emphysema. The Chartis testing under conscious sedation took significantly longer and required a higher number of measurements in total and per lobe than general anesthesia, indicating the ease of use of Chartis under general anesthesia. In the EBV-treated patients, after a collateral ventilation-negative Chartis measurement, no significant differences in TLVR were found between the conscious sedation and general anesthesia groups, suggesting no inferiority of the diagnostic value of Chartis under general anesthesia.

The observed differences in duration and number of measurements could be the result of more frequent presence of mucus, coughing, bronchus constriction, airway wall edema, and sedation problems, causing catheter obstruction in the conscious sedation group, leading to more complex procedures and more difficult interpretation of Chartis results.

There are no studies reported that compared various techniques of anesthesia with respect to feasibility. A study by Gesierich et al. [14] compared airway collapse during Chartis measurement under spontaneous breathing and jet ventilation and recommended to use spontaneous breathing to prevent airway collapse. In the patients who received general anesthesia in our study, positive pressure ventilation via an endotracheal tube was applied.

Recently, a best practice recommendations panel on endoscopic lung volume reduction favored the use of general anesthesia for Chartis measurement and the subsequent EBV placement due to the ease of use and airway and patient management [11].

Five patients received both conscious sedation as well as general anesthesia. These patients were converted from conscious sedation to general anesthesia because the treating physician was unable to perform a valid measurement under conscious sedation, due to mucus presence, patient unrest, coughing, and low flow. The fact that in some patients, measurement was only possible in a general anesthesia setting might already indicate the better feasibility of this approach.

Arguments against the use of general anesthesia for Chartis measurement could be the higher dosage of medication received, compared to conscious sedation, as well as the intubation and ventilation of severe emphysema patients. Higher cost of the application of general anesthesia should be considered, especially in limited resource settings. On the other hand, the EBV procedure is much easier and faster to perform under general anesthesia. Furthermore, at our hospital, patients are always scheduled for a combined Chartis measurement with a subsequent EBV procedure (and never for a diagnostic Chartis procedure alone to avoid an unnecessary additional bronchoscopy), making the use of general anesthesia for the Chartis procedure more practical. In addition, no anesthesia-related adverse events were reported in our patients. The use of both conscious sedation as well as general anesthesia is deemed safe in interventional pulmonology [15].

No significant differences in TLVR after treatment between the conscious sedation and general anesthesia groups were found. This is an important finding since the Chartis measurement was not yet validated under general anesthesia. The absence of collateral ventilation in combination with successful EBV placement, resulting in sufficient TLVR, is the driver for treatment success as TLVR is a predictor for clinically meaningful change after treatment [16, 17].

A higher percentage of positive collateral ventilation measurements was found in the conscious sedation technique. One explanation could be the improved patient selection over time by quantitative high-resolution computed tomography (fissure) analysis, which decreased the number of patients with positive collateral ventilation outcomes in Chartis measurement in the trials. In addition, the objective of the CHARTIS study, in which almost all patients underwent conscious sedation, was to determine whether Chartis assessment of collateral ventilation could predict significant TLVR after EBV placement, actively including patients with both negative as well as positive collateral ventilation status [8].

Baseline characteristics were significantly different for forced expiratory volume in 1 s, residual volume, and 6-minute walking distance, with the more severe patients being in the general anesthesia group. This difference can be explained by the fact that general anesthesia was more frequently applied in later trials, which were open to inclusion of patients with more severe disease. We do not believe that the severity of emphysema influenced Chartis measurement outcomes, especially because (non-)intact fissures are probably not caused by emphysematous disease, but rather reflect an inherited trait [18].

The expired total airflow volume in patients with negative collateral ventilation was significantly higher under conscious sedation than under general anesthesia. This is an interesting finding, since we assumed that patients under conscious sedation with spontaneous breathing would rely on the elasticity of the lobe to exhale through the catheter, while patients under general anesthesia would have both elasticity as well as driving force from positive pressure in the adjacent lobe(s). Another possible explanation could be that due to an easier procedure under general anesthesia, the sampling time was shorter leading to a lower amount of analyzed airflow volume. The observed difference did not lead to a difference in diagnostic outcome.

A limitation of our trial is that most Chartis measurements under conscious sedation were carried out in the earlier studies, while at that point, Chartis measurement performance experience was limited, possibly leading to a learning curve bias. A study by Herzog et al. [19], for example, described a 12% reduction of inconclusive Chartis measurements, due to increasing experience of the bronchoscopists, in a 5-year period. Another limitation of our study is that patients were retrospectively included from several trials, introducing a possible selection bias. On the other hand, we sequentially included all patients who underwent Chartis measurement at our center during the given timeframe and did not leave patients out of the analysis. In addition, we were able to include a large number of measurements compared to other retrospective studies investigating Chartis [14, 19]. Furthermore, all measurements were performed in one specialized treatment center with only two physicians performing the measurements, leading to a high level of standardization.

In conclusion, in this retrospective study we observed a significantly longer duration of the Chartis measurement as well as a higher number of attempts needed under conscious sedation compared to general anesthesia. This could indicate that the feasibility of the Chartis measurement is better under general anesthesia. The results of this study suggest advantages of performing Chartis measurement under general anesthesia, without losing diagnostic power. We recommend performing a prospective trial comparing both techniques within the same patients to validate this approach.

Disclosure Statement

J.-P.C. and E.M.v.R. developed QCT software for Pulmonx Inc USA. D.-J.S. is an advisor and investigator for Pulmonx Inc USA. J.B.A.W., J.E.H., N.H.T.t.H., I.F., H.A.M.K., and K.K. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

University of Groningen, Junior Scientific Masterclass provided financial support for the research position of J.B.A.W. This analysis was part of the SOLVE project, funded by The Dutch Lung Foundation (Longfonds) (No. 5.1.17.171).

References

- 1.Klooster K, ten Hacken NH, Hartman JE, Kerstjens HA, van Rikxoort EM, Slebos DJ. Endobronchial valves for emphysema without interlobar collateral ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2325–2335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah PL, Herth FJ. Current status of bronchoscopic lung volume reduction with endobronchial valves. Thorax. 2014;69:280–286. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey C, Zoumot Z, Jordan S, McNulty WH, Carr DH, Hind MD, Hansell DM, Rubens MB, Banya W, Polkey MI, Shah PL, Hopkinson NS. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction with endobronchial valves for patients with heterogeneous emphysema and intact interlobar fissures (the BeLieVeR-HIFi study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valipour A, Slebos DJ, Herth F, Darwiche K, Wagner M, Ficker JH, Petermann C, Hubner RH, Stanzel F, Eberhardt R, IMPACT Study., Team Endobronchial valve therapy in patients with homogeneous emphysema. Results from the IMPACT Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1073–1082. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1383OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemp SV, Slebos DJ, Kirk A, Kornaszewska M, Carron K, Ek L, Broman G, Hillerdal G, Mal H, Pison C, Briault A, Downer N, Darwiche K, Rao J, Hubner RH, Ruwwe-Glosenkamp C, Trosini-Desert V, Eberhardt R, Herth FJ, Derom E, Malfait T, Shah PL, Garner JL, Ten Hacken NH, Fallouh H, Leroy S, Marquette CH, TRANSFORM Study., Team A Multicenter RCT of Zephyr® Endobronchial Valve Treatment in Heterogeneous Emphysema (TRANSFORM) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1535–1543. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1327OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sciurba FC, Ernst A, Herth FJ, Strange C, Criner GJ, Marquette CH, Kovitz KL, Chiacchierini RP, Goldin J, McLennan G, VENT Study., Research Group A randomized study of endobronchial valves for advanced emphysema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1233–1244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberhardt R, Gompelmann D, Schuhmann M, Reinhardt H, Ernst A, Heussel CP, Herth FJF. Complete unilateral vs partial bilateral endoscopic lung volume reduction in patients with bilateral lung emphysema. Chest. 2012;142:900–908. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Gompelmann D, Ficker JH, Wagner M, Ek L, Schmidt B, Slebos DJ. Radiological and clinical outcomes of using Chartis to plan endobronchial valve treatment. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:302–308. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koster TD, Slebos DJ. The fissure: interlobar collateral ventilation and implications for endoscopic therapy in emphysema. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:765–773. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S103807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gompelmann D, Eberhardt R, Michaud G, Ernst A, Herth FJ. Predicting atelectasis by assessment of collateral ventilation prior to endobronchial lung volume reduction: a feasibility study. Respiration. 2010;80:419–425. doi: 10.1159/000319441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slebos DJ, Shah PL, Herth FJ, Valipour A. Endobronchial valves for endoscopic lung volume reduction: best practice recommendations from expert panel on endoscopic lung volume reduction. Respiration. 2017;93:138–150. doi: 10.1159/000453588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society., of Anesthesiologists Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia. ASA. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantri S, Macaraeg C, Shetty S, Aljuri N, Freitag L, Herth F, Eberhardt R, Ernst A. Technical advances: measurement of collateral flow in the lung with a dedicated endobronchial catheter system. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2009;16:141–144. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e3181a40a3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gesierich W, Samitas K, Reichenberger F, Behr J. Collapse phenomenon during Chartis collateral ventilation assessment. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1657–1667. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01973-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkiss M. Anesthesia for bronchoscopy and interventional pulmonology: from moderate sedation to jet ventilation. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:274–278. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283471227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welling JBA, Hartman JE, van Rikxoort EM, Ten Hacken NHT, Kerstjens HAM, Klooster K, Slebos DJ. Minimal important difference of target lobar volume reduction after endobronchial valve treatment for emphysema. Respirology. 2018;23:306–310. doi: 10.1111/resp.13178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valipour A, Herth FJ, Burghuber OC, Criner G, Vergnon JM, Goldin J, Sciurba F, Ernst A, VENT Study., Group Target lobe volume reduction and COPD outcome measures after endobronchial valve therapy. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:387–396. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00133012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster TD, Slebos DJ. The fissure: interlobar collateral ventilation and implications for endoscopic therapy in emphysema. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:765–773. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S103807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog D, Thomsen C, Poellinger A, Doellinger F, Schreiter N, Froeling V, Schuermann D, Temmesfeld-Wollbruck B, Hippenstiel S, Suttorp N, Huebner RH. Outcomes of endobronchial valve treatment based on the precise criteria of an endobronchial catheter for detection of collateral ventilation under spontaneous breathing. Respiration. 2016;91:69–78. doi: 10.1159/000442886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]