Abstract

Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) is a progenitor type of leukemia with ambiguous expression of lineage markers. The diagnosis of MPAL is based on flow cytometric analysis of immunophenotype, which commonly identifies myeloid lineage markers as well as B- or T-lymphoid lineage markers on leukemic blasts. Due to the rare occurrence of this disease, few studies have delineated the molecular bases of MPAL. Combining conventional karyotyping with whole genomic sequencing (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we report here our identification and characterization of chromosome translocations, gene mutations and gene expression profile in four patients with T/Myeloid MPAL, including two t(6;14)(q25;q32) one t(8;14) (q24.2;q32) and one t(7;8)(p14;q24.2). Notably, seven of the eight translocation breakpoints reside in the non-coding regions and their locations appear to be shared by two or more patients. Gene expression analysis of matched diagnostic vs. remission samples provided evidence of transcriptomes alteration involving nucleosome organization and chromatin assembly.

Keywords: Leukemic progenitor cells, cytogenetics, molecular genetics

Introduction

Recent genome-wide studies of clinical samples have advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of acute leukemia. Microarray analysis and next-generation sequencing (NGS) have demonstrated that subtypes of myeloid and lymphoid leukemia can be characterized by chromosome rearrangements, sub-microscopic DNA copy number aberrations and gene mutations. Such genetic alterations have guided risk stratification and targeted therapies in clinical practice [1,2]. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL), on the other hand, is a rare subtype of leukemia comprising less than 3% of all acute leukemias [3]. The diagnosis is based on flow cytometric analysis of immunophenotype, which commonly identifies myeloid lineage markers as well as B- or T-lymphoid lineage markers on leukemic blasts [4]. While World Health Organization (WHO) classification has defined diagnostic criteria for B/Myeloid and T/Myeloid MPAL, few studies have delineated the molecular bases of MPAL. Current understanding of MPAL pathogenesis is limited. Many MPAL patients are resistant to induction chemotherapy and those that enter remission have a high risk of relapse. There is no agreement on how the disease should be treated [3,5].

In the diagnostic setting, conventional karyotyping remains a standard method for the detection of chromosome abnormalities in acute leukemia. During our diagnostic work in the past 10 years, we performed karyotype analysis for 10 patients with MPAL. While BCR/ABL fusion, MLL rearrangement and a complex karyotype were detected in three of the four patients with B/Myeloid MPAL, previously uncharacterized translocations were revealed in four of the six patients with T/Myeloid MPAL. Considering that characterization of chromosome translocations, especially in hematological malignancies, has been one of the most efficient approaches to discover novel genes and pathways with important biological functions [6], we took a genome-wide approach by performing whole genomic sequencing (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to characterize translocation breakpoints at the molecular level and to examine gene expression profile for the four patients with T/Myeloid MPAL.

Methods

Patient samples

Diagnostic bone marrow samples from four patients with T/Myeloid leukemia and two matched remission samples were received in our laboratory for diagnostic purpose. Standard procedures for evaluating hematologic malignancies were performed, including morphology examination, flow cytometry analysis and karyotype analysis. Two normal control samples used for gene expression analysis were flow-sorted CD34 + cells from two bone marrow transplantation donors. All of the samples used in this study were preexisting clinical samples and processed in accordance with IRB approved protocols.

Karyotype and FISH analysis

Conventional karyotype analysis was performed on the four diagnostic samples and two remission samples to detect chromosome abnormalities. Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone-derived fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probes targeting chromosome 6q25 (RP11–446N2) and chromosome 14q32 (RP11–49D24 and RP11–1127D7) (BACPAC Resources, Oakland, CA) were applied to FISH experiment on the sample from patient 3, who initially showed an apparently normal karyotype. These probes and their use in FISH experiments have been described in a previous study [7].

NGS-based WGS to identify translocation breakpoints

Genomic DNA was extracted from bone marrow samples using a Gentra Puregene Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). WGS experiments were performed at Macrogen (Rockville, MD) by using the Illumina TruSeq DNA sample preparation guide and the HiSeq X sequencing platform. Macrogen provided the raw data (fastq), mapped data (bam) and called data (VCF) for subsequent analysis. Since we have the karyotype knowledge of the chromosome bands involved in the translocations, sequence analysis was assisted with visual examination using the Integrative Genome Viewer (IGV, Broad Institute, version 2.3.36) [8]. Flanking sequences from the putative breakpoints for each patient were used to design PCR primers. Subsequent PCR crossing each translocation junction was performed on patient DNA and the PCR products from each patient was subject to Sanger sequencing for breakpoint confirmation. The resulting DNA sequences were aligned to the human genome reference assembly GRCh37/hg19 with the BLAT tool.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from diagnostic and remission bone marrow samples and also from flow-sorted CD34 + cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), followed by DNase treatment. Illumina TruSeq Prep Kit was used to prepare RNA libraries. Sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer for 2×100 bp sequencing. The resulting data from each sample was analyzed at AccuraScience (Johnston, IA). Quality control (QC) was performed on the raw data using FastQC at http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Low quality bases were trimmed using Trimmomatic [9] (LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:25). The trimmed reads were aligned to the human reference genome hg19, using TopHat [10] (–read-mismatches 2–read-gap-length 2–max-insertion-length 3–max-deletion-length 3). Transcriptome assembly and gene expression quantification were performed using Cufflinks [11] -g hg19.gtf–min-isoform-fraction 0.1–min-frags-per-transfrag 10).

Differential expression analysis

Cuffdiff [11] was invoked to perform differential expression analysis for comparisons A and B and different cutoffs were used to select significant up- and down-regulated genes.

Pathway enrichment analysis

DAVID(database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery) [12] was used for pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological pathways (denoted as Gene Ontology terms) enriched among up- and down-regulated genes. FDR cutoff of 0.2 was adopted in selecting significant pathways.

GSEA analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [13] was performed using the MSigDB Gene Sets provided at http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp.

Mutation analysis

Demultiplexed fastq files generated by the sequencing platform were used to map to hg19 reference genome using BWA aligner [14] (v0.7.10). PCR duplicate removal and read pair insert size estimation is performed using Picard Tools at http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard (v1.125). Resulting alignment files in bam format are scanned for variant calls using Samtools [15] mpileup (v1.1). Variant calls are then filtered with at least 5% mutant allele frequency and an average base quality score of 25. Resulting filtered variant calls are used to annotate further with genomic information using ANNOVAR [16] (last accessed 2013-06-21). Variant calls that have been identified as common amongst populations by dbSNP at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/ were filtered out. Variant calls from WGS and RNA-seq datasets that have COSMIC [17] references were considered with likely somatic origin. Frame shift mutations in RNA-seq dataset only (not confirmed in WGS dataset) were filtered out.

Results

Detection of chromosome translocations

We routinely use conventional karyotype and FISH to provide cytogenetic diagnosis. During our diagnostic work, we detected chromosome translocations in four patients with T/Myeloid leukemia. The diagnoses were established following morphologic evaluation and immunophenotyping of bone marrow specimen from each patient (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with T/Myeloid leukemia.

| Patient ID | Sex | Age at diagnosis(years) | Immunophenotype (positive) | Karyotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 18 | CD2, cCD3, CD7, CD38, HLA-DR, CD13, CD117, MPO+/− | 46,XY,t(6;14)(q25;q32)[12]/46,XY[8] |

| 2 | M | 11 | CD2, cCD3, CD7, CD34, CD58, HLA-DR, TdT, CD13, CD117, MPO+/− | 46,XY,t(6;14)(q25;q32)[20] |

| 3 | M | 48 | CD2, cCD3, CD7, CD34, CD99, TdT, CD13, CD15, CD117, MPO+ | 46,XY,t(8;14)(q24.2;q32)[20] |

| 4 | M | 20 | CD2, cCD3, CD7, HLA-DR, CD11b, CD13, CD33, MPO+ | 46,XY,t(7;8)(p14;q24.2)[12]/46,XY[8] |

MPO: myeloperoxidase staining was weak positive for patients 1 and 2 at the beginning, but became strong positive two weeks later.

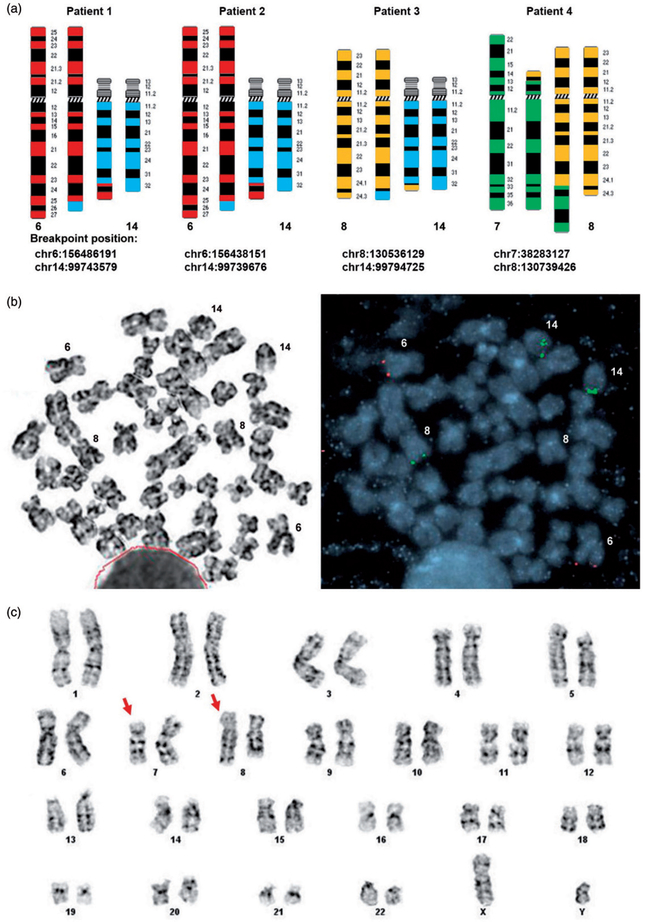

Karyotype and FISH analysis led to the identification of a translocation in each of the four patients (Figure 1(a)). The t(6;14) in patients 1 and 2 showed similar breakpoints at 6q25 and 14q32. This translocation has been documented in three additional T/Myeloid leukemia patients, although not at the molecular level [18,19]. Initial G-banding based karyotyping for patient 3 did not detect any visible translocation. Since t(6;14) is known to be recurrent in T/Myeloid leukemia and can be difficult to detect by karyotyping, we applied FISH probes targeting 6q25 and 14q32 to the third patient to evaluate the possibility of a cryptic translocation. While t(6;14) was not evident, we revealed a cryptic t(8;14), serendipitously. FISH probe targeting 14q32 showed positive hybridization signal on a third chromosome, which was determined to be chromosome 8 when FISH and G-banding were performed on the same metaphase cell (Figure 1(b)). These findings demonstrated that the 14q32 breakpoint in t(6;14) was shared by patient 3 with t(8;14). Patient 4 had a t(7;8), detected by karyotyping (Figure 1(c)). Interestingly, the breakpoint at 8q24.2 appeared to be shared by patient 3 with t(8;14) and patient 4 with t(7;8) (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Translocations in patients with T/Myeloid leukemia. (a) Schematic diagrams of translocations in four patients, with chromosome band and breakpoint indicated for each chromosome involved in the translocation. (b) FISH was performed on the same G-banded metaphase cell. FISH probes targeting 6q25 (red) and 14q32 (green) showed an extra green signal on chromosome 8, indicating a cryptic t(8;14) in patient 3. (c) Karyotype analysis detected a t(7;8)(p14;q24.2) in patient 4.

The translocation breakpoint regions of 8q24.2 and 14q32, shared by two or more of our four patients, are known to include oncogene MYC and immunoglobulin gene IgH, respectively. Using gene-specific FISH probe, we ruled out the involvement of these two genes in the four translocations.

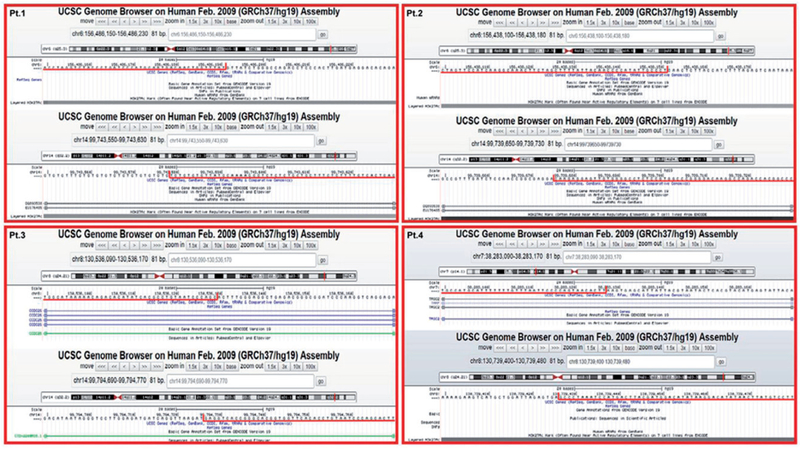

Following cytogenetic studies, we performed NGS-based WGS for each patient to determine the precise translocation breakpoints. All of the breakpoints were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing, resulting in perfect match to the genome sequences shown in Figure 2. Among the eight translocation breakpoints, one was within the T-cell receptor gamma 2 chain C (TRGC2) gene. The other seven breakpoints were all in the non-coding regions of chromosomes 6q25, 8q24.2 and 14q32. Their surrounding sequences are indicated in Figure 2 and the nearby genes can be assessed through UCSC genome browser.

Figure 2.

Genomic landscape and breakpoint sequences of four translocations. Sanger sequencing-confirmed translocation junctions are in perfect match to hg19 assembly, with sequences underlined in red on each corresponding chromosome. Patient 1 (Pt.1) had t(6;14). Patient 2 (Pt.2) also had t(6;14). Breakpoints at 14q32 in both patients were within transcript EU176485, a synthetic construct. Patient 3 (Pt.3) had t(8;14). Breakpoint at 8q24.2 was within a long non-coding RNA CCDC26 and breakpoint at 14q32 was within a long non-coding RNA CTD-2200A16.1. Patient 4 (Pt.4) had t(7;8). The breakpoint at 7p14 was within TRGC2 gene.

Detection of gene mutations

With increasing application of NGS-based sequencing in diagnostic laboratories, the list of frequently mutated genes in acute leukemia is expanding rapidly [20,21]. In order to evaluate common mutations in clinical samples from myeloid and lymphoid leukemia, our molecular diagnostic laboratory has established a mutation panel of 70 genes. With the sequencing data from WGS and RNA-seq, we analyzed mutations in these 70 genes. The names of these genes in the panel are listed in Supplementary Table 1. As summarized in Table 2, a mutation in ATRX was found in patient 1. Mutations in NRAS and WT1 were found in patient 2 and mutations in GATA3 and NOTCH1 were found in patient 4. The mutant allele frequencies were consistent with the high percentage of abnormal cells in these patients. The ATRX gene is on X chromosome and patient 1 was a male. The 100% variant allele frequency of ATRX in this patient was likely resulted from his high level of leukemic cells.

Table 2.

Mutations detected in patients with T/Myeloid leukemia.

| Patient ID | Chr: position | Gene | Base change | AA change | % VAF | Reference database ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | chrX:76856021 | ATRX | T>C | p.N1860S | 100 | COSM5001990 |

| 2 | chr1:115258745 | NRAS | C>A | p.G13C | 39.66 | COSM570 |

| 2 | chr11:32413565 | WT1 | C>G | p.R250P | 38.53 | COSM27291 |

| 4 | chr10:8106004 | GATA3 | G>A | p.R275Q | 46.15 | COSM294402 |

| 4 | chr9:139390543 | NOTCH1 | T>C | p.I2550V | 49.71 | COSM308628 |

| 4 | chr9:139391020 | NOTCH1 | G>A | p.Q2391* | 45.13 | COSM28650 |

VAF: variant allele frequency; COSM: Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database.

A nonsense mutation.

Gene expression and pathway analysis

In an attempt to identify differentially expressed genes in patients with translocations, we performed RNA-seq and analyzed gene expression profile. For the two patients with t(6;14), we had matched remission bone marrow samples, in which t(6;14) was not detectable following treatment. Therefore, gene expression levels were compared using the diagnostic samples with t(6;14) against the remission samples without t(6;14). Comparisons A (for patient 1) and B (for patient 2) are thus defined in Supplementary Table 2. When considering remission samples as a baseline, ‘up-regulated’ (or ‘down-regulated’) genes refer to the genes that were more highly (or lowly) expressed in diagnostic samples. Comparisons A and B were evaluated at multiple significance levels: at FDR cutoff of 0.05 and 0.2, and at (unadjusted) p value cutoff of.01 and.05, respectively. The number of genes with shared change of expression at each cutoff are summarized in Supplementary Figure 1. Due to the limited number of available samples, we loosened the stringency and selected genes at p value cutoff of .05 for subsequent pathway enrichment analysis.

For patients with t(8;14) and t(7;8), only diagnostic samples were available. CD34 + cells from two normal bone marrow transplantation donors were then used as baseline control for differential expression analysis. According to the genomic coordinates of the translocation breakpoints (Figure 1(a) and Figure 2), the t(7;8) placed 5’ side of TRGC2 from chromosome 7 upstream of chr8:130739426. In addition, a similar breakpoint at chr8:130536129 was found in t(8;14). These observations prompted us to test the hypothesis that promotor/enhancer of TRGC2 and/or a transcription regulator at 14q32 may have activated oncogene(s) downstream (proximal) of the chromosome 8 breakpoint. We focused our analysis on the expression of genes proximal to the 8q24.2 breakpoint. Considering that TRGC2 expression is on the reverse strand, we looked at 20 transcripts, placed downstream of TRGC2 with expression on the reverse strand. These 20 transcripts expand more than 3 Mb on the genome. Notably, an uncharacterized gene FAM49B appeared to have elevated expression in the patient with t(7;8) (Table 3). This change of expression may be associated with t(7;8), when 5’ side of the TRGC2 was placed upstream of FAM49B in the same transcription orientation.

Table 3.

Expression level of genes proximal to chromosome 8 breakpoint in t(8;14) and t(7;8).

| Gene symbol | Position of genes on chromosome 8 | CD34 donori FPKM | CD34 donor2 FPKM | t(7;8) FPKM | t(8;14) FPKM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASC19 | chr8:128,200,031–128,209,872 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CCAT1 | chr8:128,219,629–128,231,333 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.04 |

| CASC8 | chr8:128,455,595–128,494,384 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

| CASC11 | chr8:128,712,853–128,746,213 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0 |

| TMEM75 | chr8:128,958,805–128,960,969 | 0.06 | 0.34 | 0.1 | 0.15 |

| RNU4–25P | chr8:129,022,628–129,022,857 | 0 | 1.51 | 0 | 0.43 |

| LINC00977 | chr8:130,228,713–130,253,486 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0 |

| CCDC26 | chr8:130,363,940–130,365,228 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.26 |

| MIR3686 | chr8:130,496,303–130,496,388 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RP11–419K12.1 | chr8:130,691,381–130,695,925 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.26 |

| GSDMC | chr8:130,760,442–130,799,134 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 |

| FAM49B | chr8:130,851,839–130,952,118 | 51 | 46.93 | 110.26 | 56.83 |

| SNORA25 | chr8:130,880,836–130,880,962 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RNU7–181P | chr8:131,016,774–131,016,847 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MIR5194 | chr8:131,020,580–131,020,699 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ASAP1 | chr8:131,307,601–131,308,779 | 3.5 | 10.3 | 8.8 | 14.41 |

| RNU6–1255P | chr8:131,578,849–131,639,262 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KB-1568E2.1 | chr8:131,607,545–131,667,958 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

FPKM: fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

Identification of differentially expressed genes in two t(6;14) patients with matched diagnostic and remission samples has allowed enriched pathway analysis. FDR cutoff of 0.2 was used to select significant pathways. Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the results of differentially expressed genes and significantly enriched pathways. The top 10 enriched pathways are shown in Table 4 for up-regulated genes, and in Supplementary Table 3 for down-regulated genes. These results suggest that up-regulated genes in both patients with t(6;14) are associated with pathways involving nucleosome assembly, chromatin assembly, nucleosome organization, DNA packaging and chromatin assembly or disassembly (Table 4). These findings have been supported by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [13], which is independent on the number of input genes. Two top ranked gene sets up-regulated in the diagnostics samples appear to be associated nucleotide and ribonucleotide bindings (Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 4.

Gene ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of diagnostic vs. remission samples.

| GO categories/KEGG pathways | p value | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes in diagnostic sample of patient 1 | |||

| GO:0000786~nucleosome | 7.83E-23 | 1.00E-19 | |

| GO:0006334~nucleosome assembly | 7.46E-21 | 1.23E-17 | |

| GO:0031497~chromatin assembly | 1.66E-20 | 2.75E-17 | |

| GO:0065004~protein-DNA complex assembly | 4.60E-20 | 7.61E-17 | |

| GO:0034728~nucleosome organization | 7.51 E-20 | 1.24E-16 | |

| GO:0032993~protein-DNA complex | 1.17E-19 | 1.50E-16 | |

| GO:0006323~DNA packaging | 6.59E-19 | 1.09E-15 | |

| GO:0006333~chromatin assembly or disassembly | 4.21 E-18 | 6.95E-15 | |

| hsa05322:Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3.05E-14 | 3.27E-11 | |

| GO:0000785~chromatin | 7.28E-13 | 9.30E-10 | |

| Up-regulated genes in diagnostic sample of patient 2 | |||

| GO:0000786~nucleosome | 4.70E-20 | 6.19E-17 | |

| GO:0032993~protein-DNA complex | 2.32E-18 | 3.05E-15 | |

| GO:0006334~nucleosome assembly | 2.22E-17 | 3.67E-14 | |

| GO:0031497~chromatin assembly | 4.67E-17 | 7.71 E-14 | |

| GO:0065004~protein-DNA complex assembly | 1.20E-16 | 1.89E-13 | |

| GO:0034728~nucleosome organization | 1.89E-16 | 3.66E-13 | |

| GO:0006323~DNA packaging | 1.69E-15 | 2.75E-12 | |

| GO:0006333~chromatin assembly or disassembly | 9.55E-15 | 1.58E-11 | |

| hsa05322:Systemic lupus erythematosus | 8.72E-11 | 9.51 E-08 | |

| GO:0000785~chromatin | 9.41E-11 | 1.24E-07 | |

Discussion

MPAL is a high risk and difficult-to-treat leukemia. Due to the rarity of the disease, current understanding of MPAL is limited and treatment remains challenging [3,5]. Recent NGS-based WGS has led to the identification of fusion genes in a large number of acute lymphoid leukemia patients with translocations [22,23]. Other translocations have also been found in non-coding regions with regulatory function leading to altered gene expression [24]. In our four patients with T/Myeloid leukemia, none of the translocations created a fusion gene. Seven of the eight translocation breakpoints were in the non-coding regions. However, their genomic positions appear to be nonrandom. The breakpoint at 8q24.2 was shared by two and the breakpoint at 14q32 was shared by three of our four patients. Genomic amplification and altered expression of a few long non-coding RNA at 8q24.2 have been reported in hematologic and other malignancies [25–27]. The 14q32 breakpoint region is in the vicinity of BCL11B, which is a T-cell specific gene in hematopoiesis [28,29]. Rearrangements involving 14q32 have been documented in both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia [30,31]. Our expression analysis of genes surrounding the translocation breakpoints, including MYC and BCL11B, did not show consistent expression change in diagnostic samples, although we had only four samples in this study. It is worth noting that the 14q32 rearrangement could also exist as part of a complex karyotype, such as an insertional rearrangement with cryptic abnormality involving 14q32 in a patient with T/Myeloid leukemia [32].

Due to the lack of matched normal cells from our patients, we focused mutation analysis on the gene panel that is currently in use in our diagnostic laboratory to evaluate common mutations in myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. Mutations were detected in three of the four patients, including ATRX in patient 1, NRAS and WT1 in patient 2andGATA3 and NOTCH1 in patient 4. These mutations likely represent pathogenic somatic mutations, because the same mutations have been documented in Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database [17].

Two patients had translocation t(6;14), which is a recurrent translocation in T/myeloid leukemia [18,19]. We had matched diagnostic and remission samples from these two patients, so we attempted gene expression analysis on these matched samples. Although the sample size is not optimal, we observed up-regulation of genes involving nucleosome organization and chromatin assembly in the diagnostic samples, suggesting that t(6;14) may have global impact on the genome contributing to the development of T/Myeloid leukemia. In contrast to the recurrent t(6;14), neither t(8;14) nor t(7;8) reported here has been previously documented in any leukemia. In the patient with t(7;8), breakpoint at 7p14 disrupted T-cell receptor gamma 2 chain C, contributing to the T-ALL phenotype. Interestingly, rearrangement disrupting T-cell receptor delta has been reported for a patient with T/Myeloid leukemia, leading to overexpression of ADAMTS2 [32]. We provided evidence that the 5’ side of the TCRG2 may have activated an uncharacterized gene FAM49B due to the translocation. Functional study of this gene will help to clarify its significance. In addition, two mutations in NOTCH1 were detected in this patient with t(7;8). In a previous study by Eckstein et al., mutations in NOTCH1 were identified in four patients with T/Myeloid leukemia [33].

In summary, we detected translocations in four T/Myeloid leukemia patients, with two t(6;14)(q25;q32), one t(8;14)(q24.2;q32) and one t(7;8)(p14;q24.2). While t(6;14) is recurrent in T/Myeloid leukemia, the other two are reported here for the first time. None of these translocations created a fusion gene. The 14q32 region, with breakpoints shared by three of our four patients, likely contains important regulatory elements involving the development of T/myeloid leukemia. Interestingly, a far downstream enhancer for murine BCL11b has been found to control T-cell specific expression [29]. In addition, the finding of increased expression of genes involving nucleosome organization and chromatin assembly in diagnostic samples indicate that translocations in the non-coding region may have global impact on the genome. Studies of additional patient samples will lead to better understanding of the pathogenesis of T/Myeloid leukemia and also improve clinical management of this high risk leukemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Johns Hopkins Sequencing Core for performing RNA-sequencing.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, USA [P30CA006973].

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Potential conflict of interest: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2017.1372577.

References

- [1].Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Roberts KG, Mullighan CG. Genomics in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: insights and treatment implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:344–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim HJ. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) and beyond. Blood Res. 2016;51:215–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Porwit A, Béné MC. Acute leukemias of ambiguous origin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:361–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wolach O, Stone RM. How I treat mixed-phenotype acute leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:2477–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rowley JD. Chromosomal translocations: revisited yet again. Blood. 2008;112:2183–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yu L, Reader JC, Chen C, et al. Activation of a novel palmitoyltransferase ZDHHC14 in acute biphenotypic leukemia and subsets of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world’s knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D805–D811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Batanian JR, Dunphy CH, Gale G, et al. Is t(6;14) a non-random translocation in childhood acute mixed lineage leukemia? Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;90: 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Georgy M, Yonescu R, Griffin CA, et al. Acute mixed lineage leukemia and a t(6;14)(q25;q32) in two adults. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;185:28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Neumann M, Vosberg S, Schlee C, et al. Mutational spectrum of adult T-ALL. Oncotarget. 2015;6: 2754–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gu Z, Churchman M, Roberts K, et al. Genomic analyses identify recurrent MEF2D fusions in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Comms. 2016;7:13331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nagel S, Scherr M, Kel A, et al. Activation of TLX3 and NKX2–5 in t(5;14)(q35;q32) T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia by remote 3’-BCL11B enhancers and coregulation by PU.1 and HMGA1. Cancer Res. 2007;67: 1461–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Huppi K, Pitt JJ, Wahlberg BM, et al. The 8q24 gene desert: an oasis of non-coding transcriptional activity. Front Gene. 2012;3:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chinen Y, Sakamoto N, Nagoshi H, et al. 8q24 amplified segments involve novel fusion genes between NSMCE2 and long noncoding RNAs in acute myelogenous leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hirano T, Yoshikawa R, Harada H, et al. Long noncoding RNA, CCDC26, controls myeloid leukemia cell growth through regulation of KIT expression. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Liu P, Li P, Burke S. Critical roles of Bcl11b in T-cell development and maintenance of T-cell identity. Immunol Rev. 2010;238:138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li L, Zhang JA, Dose M, et al. A far downstream enhancer for murine Bcl11b controls its T-cell specific expression. Blood. 2013;122:902–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Su XY, Della-Valle V, Andre-Schmutz I, et al. HOX11L2/TLX3 is transcriptionally activated through T-cell regulatory elements downstream of BCL11B as a result of the t(5;14)(q35;q32). Blood. 2006;108:4198–4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Abbas S, Sanders MA, Zeilemaker A, et al. Integrated genome-wide genotyping and gene expression profiling reveals BCL11B as a putative oncogene in acute myeloid leukemia with 14q32 aberrations. Haematologica. 2014;99:848–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tota G, Coccaro N, Zagaria A, et al. ADAMTS2 gene dysregulation in T/myeloid mixed phenotype acute leukemia. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Eckstein OS, Wang L, Punia JN, et al. Mixed-phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) exhibits frequent mutations in DNMT3A and activated signaling genes. Exp Hematol. 2016;44:740–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.