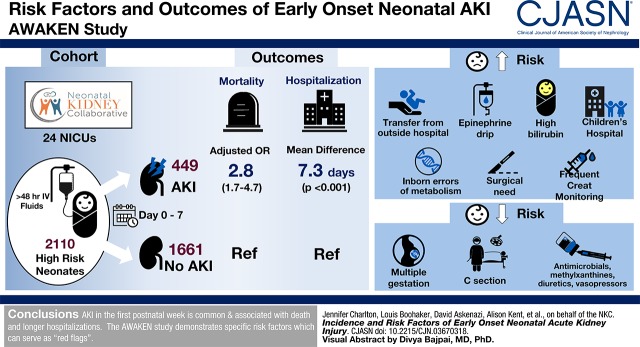

Visual Abstract

Keywords: Children, neonatal kidney collaborative, Infant, Newborn, child, Pregnancy, Incidence, methylxanthine, Gestational Age, creatinine, Intensive Care Units, Neonatal, diuretics, risk factors, Anti-Infective Agents, Retrospective Studies, Mating Factor, Xanthines, Acute Kidney Injury, Vasoconstrictor Agents, Epinephrine, hospitalization, Cesarean Section, Hyperbilirubinemia

Abstract

Background and objectives

Neonatal AKI is associated with poor short- and long-term outcomes. The objective of this study was to describe the risk factors and outcomes of neonatal AKI in the first postnatal week.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The international retrospective observational cohort study, Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates (AWAKEN), included neonates admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit who received at least 48 hours of intravenous fluids. Early AKI was defined by an increase in serum creatinine >0.3 mg/dl or urine output <1 ml/kg per hour on postnatal days 2–7, the neonatal modification of Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria. We assessed risk factors for AKI and associations of AKI with death and duration of hospitalization.

Results

Twenty-one percent (449 of 2110) experienced early AKI. Early AKI was associated with higher risk of death (adjusted odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.7 to 4.7) and longer duration of hospitalization (parameter estimate: 7.3 days 95% confidence interval, 4.7 to 10.0), adjusting for neonatal and maternal factors along with medication exposures. Factors associated with a higher risk of AKI included: outborn delivery; resuscitation with epinephrine; admission diagnosis of hyperbilirubinemia, inborn errors of metabolism, or surgical need; frequent kidney function surveillance; and admission to a children’s hospital. Those factors that were associated with a lower risk included multiple gestations, cesarean section, and exposures to antimicrobials, methylxanthines, diuretics, and vasopressors. Risk factors varied by gestational age strata.

Conclusions

AKI in the first postnatal week is common and associated with death and longer duration of hospitalization. The AWAKEN study demonstrates a number of specific risk factors that should serve as “red flags” for clinicians at the initiation of the neonatal intensive care unit course.

Introduction

Single-center studies suggest that neonatal AKI affects 18%–70% of critically ill neonates and is associated with poor outcomes (1–7). Although these studies have reported the epidemiology and risk factors associated with AKI over the entire neonatal period, none have examined AKI at particular postnatal periods. It may be important to differentiate the epidemiology of neonatal AKI by the timing of the event, because the etiology of AKI could differ during a prolonged hospital stay. Neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) have extended hospital courses with a variety of exposures spanning various stages of kidney development which influence their risk for AKI. The first week after birth is a vulnerable time for the development of neonatal AKI due to antenatal, intrapartum, and early postnatal transition factors. Specifically, during the transition into the extrauterine environment, the normal neonatal kidney physiology (with an inherently low GFR) predisposes this immature kidney to AKI. Because the neonate’s serum creatinine will reflect maternal values at birth which then evolve over the next few postnatal days to find a new “steady state,” the definition of neonatal AKI in the first week may differ from other time points. Additionally, a comprehensive evaluation of the risk factors for AKI during the first week after birth would help clinicians to identify vulnerable neonates and researchers to select at-risk infants for enrollment into future prospective interventional studies designed to reduce the prevalence of AKI shortly after birth.

In 2014, the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative was established and performed the multicenter study Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney injury Epidemiology in Neonates (AWAKEN) (8). AWAKEN was the first multicenter study designed to evaluate neonatal AKI among critically ill neonates. We have recently published data from the AWAKEN study which includes the incidence and outcomes of neonates who experience AKI during their entire neonatal hospitalization (9). Using the AWAKEN database, we hypothesize that the risk for AKI and the factors influencing that risk change according to gestational age and postnatal age. In order to improve the understanding of neonatal AKI during the first week after birth, we performed an analysis to (1) determine whether early AKI was associated with poor short-term outcomes and (2) determine the perinatal risk factors associated with early AKI across the gestational age continuum.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

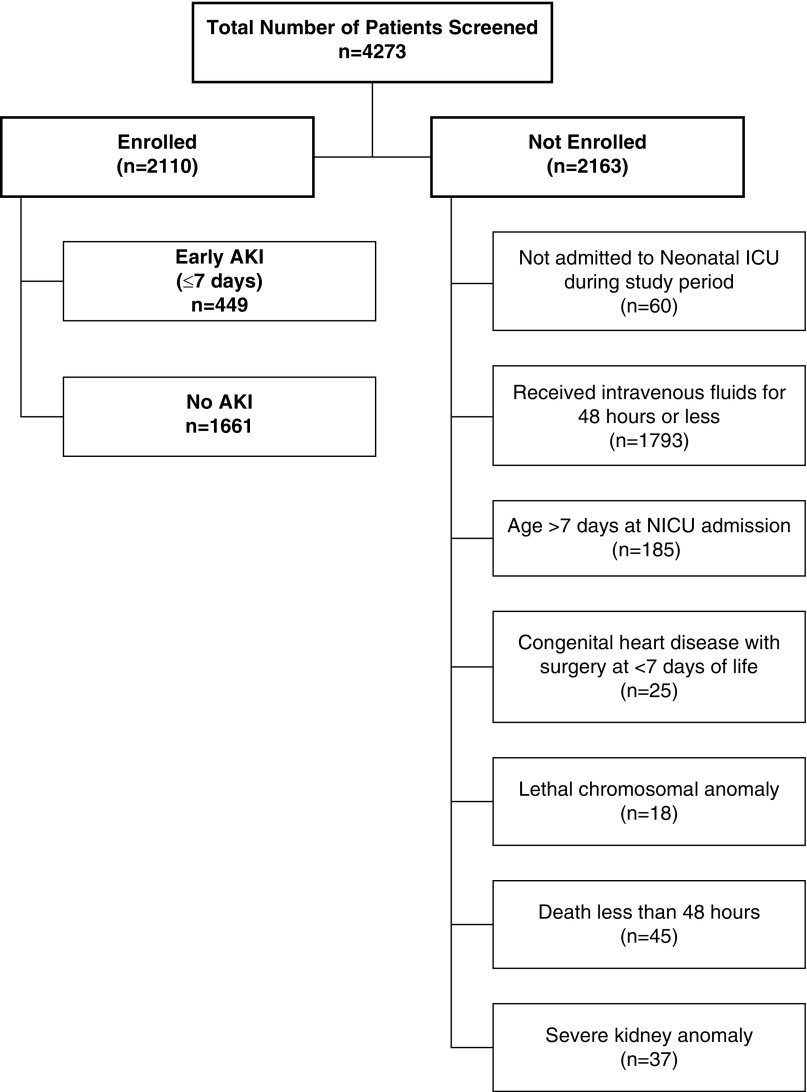

AWAKEN is an international, retrospective, multicenter cohort study of neonates admitted to 24 neonatal ICUs participating in the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative. The centers included in the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative were self-identified; however, each center was required to have an engaged pediatric nephrologist and neonatologist. Each center received approval from their Human Research Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board. A detailed description of the methodology and the included institutions was published (8). Briefly, data were collected from January 1, 2014 to March 31, 2014 on each subject. For inclusion, neonates had to receive >48 hours of intravenous fluids. Exclusion criteria included admission >7 days after birth or death <48 hours after birth, lethal chromosomal or severe congenital kidney anomaly, or congenital heart disease requiring repair <7 days after birth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Enrollment of Patients into the AWAKEN study: screening and enrollment of subjects experiencing early onset AKI. Early AKI was defined as occurring within the first 7 days after birth and is based on changes in serum creatinines from the lowest prior serum creatinine or urine output. Those with insufficient data to define neonatal AKI were included in the no AKI group. Severe kidney anomalies were defined as vesicoureteral reflex grades 4 or 5, moderate or severe hydronephrosis, bilateral hypoplasia, dysplasia, or agenesis, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, or posterior urethral valves. ICU, intensive care unit; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Definition of AKI

Early neonatal AKI was defined by the neonatal modification of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria (10–13) as occurring within the first 7 days after birth. AKI was defined by (1) an increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dl, (2) a risk of serum creatinine >50% more than the previous value, or (3) urine output <1 ml/kg per hour during a 24-hour period from days 2 to 7. Further details of the AKI stages are included in Supplemental Table 1. Of note, there were 140 patients who did not have sufficient serum creatinine or urine output data to determine AKI status. In a prior description of the AWAKEN cohort, a base-case, worst-case sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether a possible selection bias exists among those with inadequate data to classify AKI (9). The results of the sensitivity analysis found no difference in mortality and length of stay outcomes by AKI status, suggesting that there exists no selection bias from the inclusion of the 140 missing AKI statuses.

Outcomes

The outcome of death was assessed over the time period of birth to 30 postnatal days or discharge from the hospital. As outlined in the AWAKEN methods paper (8), data were collected from admission until discharge from the neonatal ICU, death, or 120 days after birth. Duration of hospitalization was defined for neonates who died in the hospital by the number of days in the neonatal ICU.

Risk Factors for AKI

Daily details were collected regarding fluid prescription, electrolytes, vital signs, and medications from days 1–7. The rationale for collecting the exposure variables was on the basis of previous retrospective studies (8,14–19). Admission diagnoses were extracted from the patient’s chart. Case report forms and manual of operations are provided in the supplemental materials of a study by Jetton et al. (8). Data on congenital anomalies were extracted from kidney ultrasound reports and dichotomized into mild-to-moderate and severe congenital kidney anomalies (Supplemental Table 2).

Nephrotoxic medications were categorized as such in accordance with published studies (20) with the exception of cephalosporin use. Other medication exposures relevant to the neonatal ICU included methylxanthines, vasopressors, and diuretics (Supplemental Table 3). Medication exposure was categorized as being given before the AKI event.

We assessed institutional factors including the median number of serum creatinine measurements and the type of assay. Frequency and methodology for laboratory monitoring were center-dependent (Supplemental Table 4). No adjustment was made for the type of creatinine assay because the AKI definition is on the basis of a change from baseline. Each site was categorized as a perinatal center (neonatal ICU providing care for neonates requiring medical care for their indication for admission), perinatal/surgical center (neonatal ICU providing surgical services), or children’s hospital without perinatal services (neonatal ICU providing care for neonates with advanced surgical services including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). All data were stored in a web-based database, MediData Rave, housed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Statistical Analyses

Categoric variables were analyzed by proportional differences with the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. The nonparametric continuous variables were analyzed by Wilcoxon rank sum tests and reported as the median and interquartile ranges. The normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using t tests and reported as means and SD.

To assess the association of early AKI and death within the entire cohort, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Because of the limited number of outcomes, the following variables were selected to be included in the model: early AKI, intubation, gestational age, 1-minute Apgar score, and admission for inborn errors of metabolism or congenital heart disease. To determine the association between early AKI and length of stay in the whole group and the gestational age strata, linear regression was used to calculate crude parameter estimates and 95% CIs. Regression models used a backward procedure with a significance level of 0.2 of stay. To examine the association of AKI severity with mortality and length of stay, time-to-event analysis for survival with Kaplan–Meier analysis of the entire cohort and for each gestational age category was performed, with P<0.05 considered to be significant.

A generalized estimating equation logistic model accounting for clustering by study center was used to estimate ORs and associated 95% CIs for each of the potential risk factors for AKI. Models were created separately for maternal, neonatal, and medication characteristics. Within each analysis, crude ORs were estimated in addition to age, ethnicity, and both Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes–adjusted and then fully adjusted (i.e., for age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and -5 in addition to the other variables of interest). In a supplemental analysis, all of the maternal, neonatal, and medication characteristic variables were considered for inclusion into a single generalized estimating equation logistic regression model; the most parsimonious model was chosen using a stepwise selection process with a model α-level threshold of 0.10 for entry into the model and of 0.10 for remaining in the model. Models were created for the overall study population and then separately for each gestational age group. Finally, Pearson correlation was used to assess the strength of association between median serum creatinine counts and AKI prevalence by institution.

Results

Demographics

Of the 4273 neonates screened, 2110 were included in this analysis (Figure 1). Demographics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the overall cohort of AWAKEN with and without early AKI and stratified into gestational age cohorts (22–28, 29–35, ≥36 wk)

| Characteristic | Overall Cohort (n=2110) | 22–28 wk (n=265) | 29–35 wk (n=936) | ≥36 wk (n=909) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI (n=449) | No AKI (n=1661) | AKI (n=75) | No AKI (n=190) | AKI (n=127) | No AKI (n=809) | AKI (n=247) | No AKI (n=662) | |

| Gestational age, wk | 34.6±5.2 | 34.0±4.2 | 25.0±1.5 | 26.0±1.6 | 32.7±2.0 | 32.5±1.8 | 38.4±1.5 | 38.1±1.5 |

| Birth weight, g | 2479±1085 | 2249±962 | 797±198 | 900±258 | 2047±693 | 1871±562 | 3213±618 | 3101±703 |

| Sex (male) | 269 (60) | 932 (56) | 44 (59) | 105 (55) | 71 (56) | 449 (56) | 154 (62) | 378 (57) |

| Race (White) | 265 (59) | 916 (55) | 38 (51) | 87 (46) | 72 (57) | 457 (57) | 155 (63) | 372 (56) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 43 (10) | 243 (15) | 13 (17) | 14 (7) | 9 (7) | 129 (16) | 21 (9) | 100 (15) |

| Apgar-1 | 6 (3, 8) | 7 (4, 8) | 4 (1, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 7 (4, 8) | 7 (5, 8) | 8 (4, 8) | 8 (5, 9) |

| Apgar-5 | 8 (6, 9) | 8 (7, 9) | 6 (4, 8) | 7 (6, 8) | 8 (7, 9) | 8 (8, 9) | 9 (6, 9) | 9 (7, 9) |

| Antimicrobialsa | 195 (43) | 1258 (76) | 44 (59) | 179 (94) | 58 (46) | 611 (76) | 93 (38) | 468 (71) |

| Methylxanthinesa | 60 (13) | 467 (28) | 36 (48) | 173 (91) | 20 (16) | 270 (33) | 4 (2) | 24 (4) |

| Diureticsa | 15 (3) | 70 (4) | 2 (3) | 16 (8) | 4 (3) | 10 (1) | 9 (4) | 44 (7) |

| Vasopressorsa | 38 (9) | 140 (8) | 17 (23) | 40 (21) | 6 (5) | 35 (4) | 15 (6) | 65 (10) |

| NSAIDsa | 13 (3) | 77 (5) | 13 (17) | 68 (36) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| AKI by creatinine | 224 (50) | 0 | 70 (93) | 0 | 75 (59) | 0 | 79 (32) | 0 |

| AKI by urine output | 282 (62) | 0 | 10 (73) | 0 | 68 (53) | 0 | 204 (83) | 0 |

| Mortality | 37 (8) | 40 (2) | 17 (23) | 20 (11) | 10 (8) | 8 (1) | 10 (4) | 12 (2) |

| Length of stay, d | 33±42 | 30±31 | 80±47 | 81±40 | 33±48.0 | 29±22 | 19±21 | 17±20 |

Data are shown as mean±SD or n (%) and Apgar are median and IQR. Antimicrobial medications: acyclovir, amphotericin B, aminoglycosides, piperacillin-tazobactam, and vancomycin; methylxanthine medications: caffeine and theophylline; diuretic medications: bumetanide, chlorothiazide, furosemide, and spironolactone; vasopressor medications: dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone, norepinephrine, and dopamine; and NSAID medications: indomethacin and ibuprofen. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. AWAKEN, Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates.

All medications were given before the episode of AKI.

Early Neonatal AKI

Early AKI was identified in 449 (21%) of the 2110 enrolled neonates, representing 11% of the entire neonatal ICU population (449 of 4273), assuming that all nonenrolled infants did not have AKI. Of the 449 with AKI, 216 had stage 1 (48%), 105 had stage 2 (23%), and 128 had stage 3 (29%) (Figure 2). Twenty-three neonates received kidney replacement therapy in the first week. The rate of early neonatal AKI varied within the gestational age cohorts: 22–28 weeks (n=75, 28%), 29–35 weeks (n=127, 14%), and ≥36 weeks (n=247, 27%). The mean number of days between birth and the first episode of AKI was 2.8±1.8 days. AKI was diagnosed by serum creatinine in 224 of 449, by urine output in 282 of 449, and by both serum creatinine and urine output criteria in 57 of 449. Of the 449 with early AKI, 79 (18%) had an additional episode within the first 7 days.

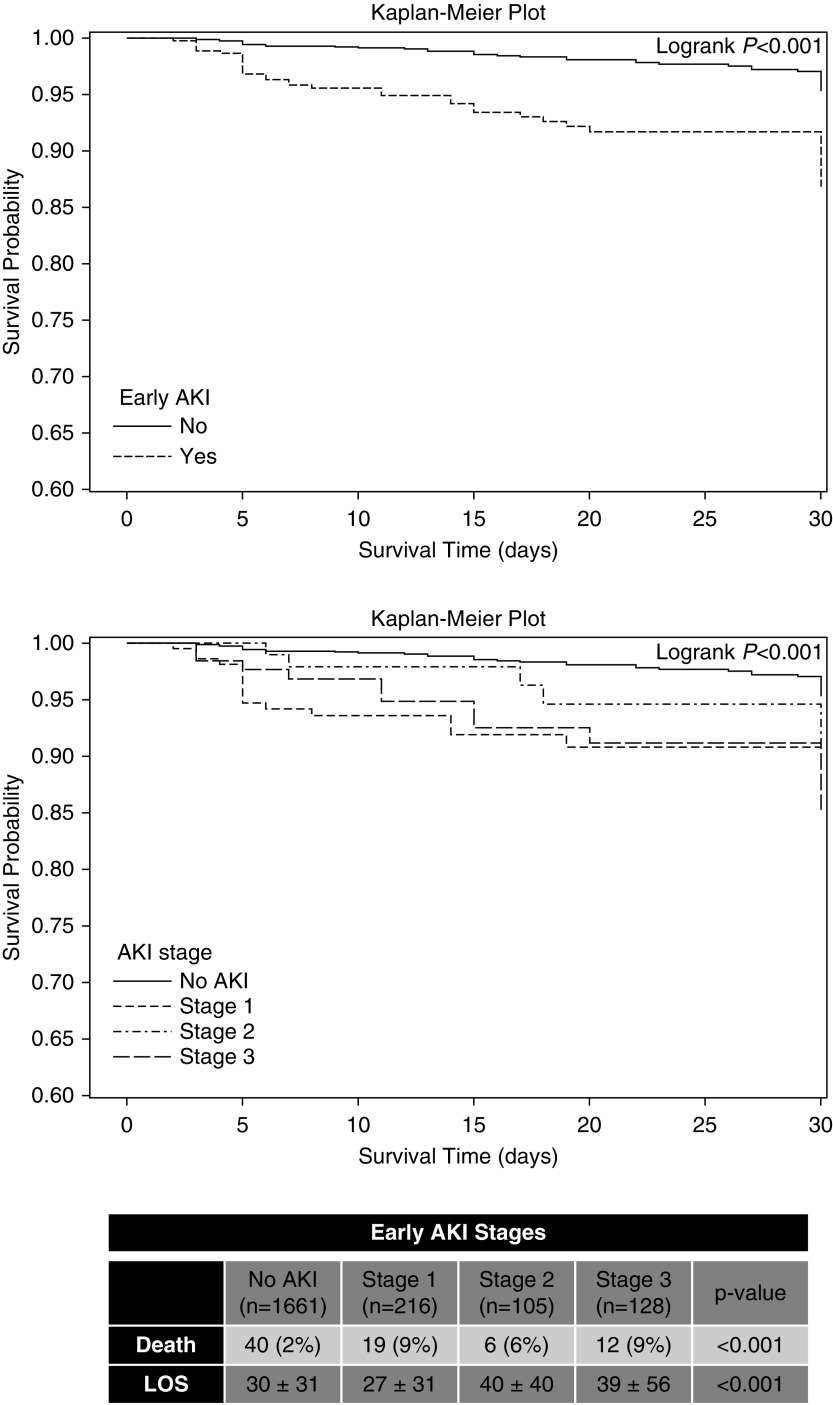

Figure 2.

Early neonatal AKI is independently associated with death and longer hospitalizations. Early AKI survival outcome curves for the entire cohort and for all stages of AKI and early AKI survival outcome curves for stage of AKI. Tabulated data show mortality and length of stay for early AKI by stage of AKI. LOS, length of stay.

Outcomes: Mortality and Length of Stay

In the whole cohort, more deaths occurred in those with early AKI compared with those without AKI (8% [n=37] versus 2% [n=40]). Early AKI was independently associated with a higher mortality in both the crude (OR, 3.6; 2.3 to 5.8; P<0.001) and adjusted models (adjusted OR, 2.8; 1.7 to 4.7; P<0.001; Figure 2). However, because of small numbers in each of the gestational age strata, we did not stratify by each gestational age cohort.

Early AKI exposure was independently associated with longer length of hospitalization stay than those without AKI only in adjusted models for the overall cohort (mean difference 7.3 days, P<0.001) (Table 2). A similar adjusted association was observed for the 22–28-week cohort (mean difference 6.5 days, P=0.04), and an attenuated yet significant association was observed for the ≥36-week cohort (mean difference 4.9 days, P=0.004); there was no significant difference by AKI status in the length of hospitalization for the 29–35-week cohort (mean difference 3.7 days, P=0.08). AKI stages 2 and 3 were associated with approximately 10-day-longer hospitalizations than those without AKI (no AKI: 30±31, AKI stage 2: 40±40, stage 3: 39±56 days; Figure 2).

Table 2.

The association between early AKI and length of stay (d), assessing the overall cohort and by gestational age cohorts (22–28, 29–35, ≥36 wk)

| Variable | Non-AKI (mean±SD) | AKI (mean±SD) | Unadjusted Difference (d) (95% CI) | P Valuea | Adjusted Difference (d) (95% CI) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | 29±29 | 32±33 | 2.4 (−0.8 to 5.5) | 0.14 | 7.3 (4.7 to 10.0) | <0.001 |

| 22–28 wk | 78±35 | 76±41 | −1.9 (−8.2 to 4.5) | 0.56 | 6.5 (0.4 to 12.6) | 0.04 |

| 29–35 wk | 28±22 | 30±24 | 1.2 (−3.2 to 5.6) | 0.59 | 3.7 (−0.5 to 7.9) | 0.08 |

| ≥36 wk | 16±19 | 19±21 | 2.8 (−0.6 to 6.3) | 0.11 | 4.9 (1.6 to 8.2) | 0.004 |

Unadjusted and adjusted differences are shown as parameter estimates.

On the basis of general linear regression.

Linear regression adjusted for early AKI, positive pressure ventilation, intubation, sepsis, seizures/hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, admission for necrotizing enterocolitis, admission for omphalocele, size for gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction, hydramnios, multiple gestation, meconium, steroids for fetal maturation, 1-min Apgar, 5-min Apgar, exposure to nephrotoxins, methylxanthines, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and admission for other reasons.

Risk Factors for Early Neonatal AKI

Among maternal conditions, multiple gestations were associated with 50% lower odds of early AKI and scheduled cesarean section (compared with vaginal birth) was associated with a 30% lower likelihood of early AKI after adjustment for maternal demographics, Apgar-1 and -5, and the other maternal condition characteristics (Table 3). Among neonatal conditions—in the fully adjusted model—higher odds of early AKI were observed for transfer from an outside hospital, resuscitation with epinephrine, and admission diagnoses of hyperbilirubinemia, inborn errors of metabolism, and surgical need (Table 4). For medication-, institution-, and creatinine-related characteristics, higher odds of early AKI were observed in the fully adjusted model for more frequent creatinine monitoring and admission to a children’s hospital, whereas exposure to antimicrobial medications, methylxanthines, diuretics, and vasopressors was associated with lower likelihood of AKI (Table 5). There was a significant correlation between a higher number of serum creatinine measurements and AKI, particularly prominent in the 22–28-week group (Supplemental Figure 1).

Table 3.

Association of maternal conditions and fetal exposures with early AKI in the full AWAKEN cohort

| Variable | Non-AKI (%) | AKI (%) | Partially Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P Value | Fully Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of gestations | ||||||

| Single | 1337 (81) | 404 (90) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Multiple | 324 (20) | 45 (10) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.8) | 0.004 |

| Steroids for fetal maturation | 628 (38) | 117 (26) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | <0.01 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.10 |

| Hypertensive disease during pregnancy | 375 (23) | 74 (17) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 0.05 | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.14 |

| Amniotic fluid | ||||||

| Oligohydramnios | 78 (5) | 21 (5) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.89 | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.84 |

| Normal | 1526 (92) | 407 (91) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Polyhydramnios | 57 (3) | 21 (5) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.28 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.25 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 650 (41) | 215 (51) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Cesarean section, scheduled | 231 (15) | 45 (11) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | <0.001 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.003 |

| Cesarean section, unscheduled | 699 (44) | 159 (38) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.02 | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 0.09 |

| Meconium exposure | 173 (10) | 62 (14) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.7) | 0.50 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) | 0.66 |

AWAKEN, Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, reference; —, not applicable.

Estimated from a generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and -5.

Estimated from a GEE logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and -5 in addition to other variables in the table.

Table 4.

Associations of neonatal conditions and exposures with early AKI in the full AWAKEN cohort

| Variable | Non-AKI (%) | AKI (%) | Partially Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P Value | Fully Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery site | ||||||

| Inborn | 1085 (65) | 172 (38) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Outborn | 576 (35) | 277 (62) | 2.8 (1.7 to 4.5) | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.6 to 4.0) | <0.001 |

| Size | ||||||

| Small for gestational age | 359 (22) | 84 (19) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | 0.45 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 0.76 |

| Normal for gestational age | 1219 (74) | 330 (74) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Large for gestational age | 79 (5) | 33 (7) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.1) | 0.11 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.06 |

| Intubation | 391 (24) | 145 (32) | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.0) | 0.44 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.95 |

| Chest compressions | 48 (3) | 36 (8) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.94 | |

| Epinephrine | 16 (1) | 22 (5) | 2.5 (1.3 to 4.9) | <0.01 | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.1) | 0.03 |

| Saline bolus | 46 (3) | 34 (8) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.0) | 0.09 | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 0.67 |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy/seizures | 104 (6) | 63 (14) | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.2) | 0.15 | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) | 0.50 |

| Hypoglycemia | 197 (12) | 40 (9) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.19 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.14 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 40 (2) | 23 (5) | 2.3 (1.3 to 4.1) | 0.003 | 2.4 (1.4 to 3.9) | <0.001 |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | 10 (0.6) | 9 (2) | 3.9 (1.5 to 9.8) | 0.004 | 3.3 (1.4 to 7.8) | <0.01 |

| Congenital heart disease | 64 (4) | 25 (6) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 0.11 | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.5) | 0.06 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 7 (0.4) | 6 (1) | 2.9 (1.0 to 8.3) | 0.06 | 2.1 (0.8 to 5.7) | 0.14 |

| Surgical need | 55 (3) | 34 (8) | 2.5 (1.4 to 4.3) | 0.001 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.8) | <0.01 |

| Kidney abnormalities | ||||||

| None | 1608 (97) | 433 (97) | ||||

| Mild-to-moderate kidney anomalies | 50 (3) | 15 (3) | 0.9 (0.1 to 10.8) | 0.90 | 1.4 (0.2 to 9.8) | 0.76 |

AWAKEN, Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, XXX; —, XXX.

Estimated from a generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and -5.

Estimated from a GEE logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and -5 in addition to other variables in the table.

Table 5.

Associations of medications and types of institutions with early AKI in the full Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates cohort

| Variable | Non-AKI (%) | AKI (%) | Partially Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P Value | Fully Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial medicationsc | ||||||

| No | 403 (24) | 254 (57) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Yes | 1258 (74) | 195 (43) | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.3) | <0.001 |

| Methylxanthinesc | ||||||

| No | 1194 (72) | 389 (87) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Yes | 467 (28) | 60 (13) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) | <0.001 |

| Diureticsc | ||||||

| No | 1591 (96) | 434 (97) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Yes | 70 (4) | 115 (3) | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.12 | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.0) | 0.04 |

| Vasopressorsc | ||||||

| No | 1521 (92) | 411 (92) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Yes | 140 (8) | 38 (9) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.11 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.01 |

| NSAIDsc | ||||||

| No | 1584 (95) | 436 (97) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Yes | 77 (5) | 13 (3) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.5) | 0.25 | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.2) | 0.62 |

| Mean serum creatinine measurements | 3±3 | 5±4 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | <0.001 |

| Site type | ||||||

| Children’s hospital | 422 (25) | 255 (57) | 3.8 (2.2 to 6.6) | <0.001 | 2.8 (1.6 to 5.0) | 0.001 |

| Perinatal | 307 (19) | 56 (13) | ||||

| Perinatal/surgical | 932 (56) | 138 (31) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Creatinine method | ||||||

| Enzymatic | 1250 (77) | 324 (76) | Ref | — | Ref | — |

| Jaffe | 368 (23) | 105 (25) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.3) | 0.91 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) | >0.99 |

| Sites outside of the USA | 217 (13) | 43 (10) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) | 0.20 | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 0.89 |

Antimicrobial medications: acyclovir, amphotericin B, aminoglycosides, piperacillin-tazobactam, and vancomycin; methylxanthine medications: caffeine and theophylline; diuretic medications: bumetanide, chlorothiazide, furosemide, and spironolactone; vasopressor medications: dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone, NE, and dopamine; and NSAID medications: indomethacin and ibuprofen. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref, XXX; —, XXX; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Estimated from a generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and 5.

Estimated from a GEE logistic model accounting for clustering by study center and adjusted for gestational age, ethnicity, and Apgar-1 and 5 in addition to other variables in the table.

All medications were given before the episode of AKI.

The majority of factors that were associated with neonatal AKI in the 22–28-week group were medication exposures ( Supplemental Figure 2). Antimicrobial agents, methylxanthines, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), hypertensive disease during pregnancy, and hypoglycemia were all associated with lower adjusted odds of developing early AKI. More frequent monitoring was associated with higher adjusted odds of early AKI. In the 29–35-week group, outborn delivery, saline bolus during resuscitation, and more frequent creatinine monitoring were all associated with higher risk for early AKI; however, antimicrobial and methylxanthine exposure were associated with lower adjusted odds of AKI. For the ≥36-week group, outborn status, more frequent monitoring of creatinine, and hyperbilirunemia (unique to this age group) were associated with higher adjusted odds for early AKI. However, antimicrobial, methylxanthine, and vasopressor exposures were associated with lower adjusted odds for early AKI.

Discussion

This study represents the largest evaluation of the epidemiology and risk factors associated with neonatal AKI in the first week after birth using an international, multicenter cohort of >2000 neonates inclusive of all gestational ages. Early neonatal AKI is associated with greater mortality and longer length of stay. These data reinforce known risk factors, highlight new risk factors, and demonstrate the need to standardize kidney function–monitoring practices for the early detection of neonatal AKI. The data presented are relevant to clinicians to inform surveillance guidelines and establish risk stratification strategies for future interventional studies.

High-risk neonates who develop AKI in the first week are at nearly three-times-higher adjusted odds of death than those who did not have AKI. Neonates with stage 1 AKI had a similar risk of death (9%) to those with stage 3, suggesting that some of those with stage 1 AKI might have progressed if they had not died. In the first week, 3.7% of the cohort had a second episode of AKI. Although the events were separated by a new serum creatinine baseline or an increase in urine output, the “second” AKI could represent a continuation of the first event. However, the distinction between more frequent episodes and a longer duration of AKI may have a similar effect on future kidney dysfunction. In a small follow-up study of very-low-birth-weight infants, the duration of AKI (measured by serum creatinine >1.0 mg/dl) and the number of AKI events were both risk factors in the development of kidney dysfunction at the average age of 5 years (21). Further work is needed to determine the significance of “recurrent” AKI in the neonatal ICU.

Several unique risk factors have emerged from AWAKEN. Outborn delivery requiring retrieval of the infant has been recognized as a risk factor for poorer outcomes in many neonatal studies (22); AWAKEN has demonstrated that being born outside of and requiring transfer to a tertiary care center is a risk factor for early AKI. Whether the risk for AKI is secondary to a sicker population of infants who require transfer or due to general resuscitation, there may be physiologic strategies to consider to reduce early AKI for a prospective study. Admission to the NICU for a surgical condition was associated with higher risk of early AKI. The types of surgical interventions were not available in the AWAKEN database, but warrant further study. Lastly, the admission diagnosis of hyperbilirubinemia was found to be associated with early AKI. There are many factors that could influence this association: hemolysis on tubular function (23), phototherapy (24–26), anemia, exchange transfusion therapy, and dehydration. Further investigation of the timing, types of therapeutic interventions, and biases inherent to a population of neonates admitted to the NICU for hyperbilirubinemia is necessary to delineate this pathophysiology.

Several maternal factors, including steroid administration for fetal lung maturity and hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, were associated with lower risk of neonatal AKI before adjustment for center effect. The use of antenatal betamethasone reduces complications related to prematurity: respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, and necrotizing enterocolitis (27). Glucocorticoid therapy increases mean arterial pressure, kidney blood flow, and GFR in preterm lambs, baboons, and human neonates (28–30), indicating induction of kidney maturity. However, this may incur a long-term cost, with animal models showing alterations in the renin-angiotensin system, reduction of nephron number, and long-term hypertension (31–36). Endogenous steroid exposure may also result in accelerated maturity of the fetal kidney. Preeclampsia is associated with decreased activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2, an enzyme critical for cortisol metabolism in the placenta. A reduction of this enzyme in preeclamptic mothers may result in greater steroid exposure to the fetus, again resulting in accelerated kidney maturation. Alternatively, infants whose mothers had preeclampsia may be less likely to develop AKI secondary to bias by indication. It is possible that infants delivered for maternal preeclampsia were “healthier” than premature infants who were delivered for other reasons. Despite studies demonstrating that neonates of preeclamptic mothers have a lower risk for neonatal AKI, it is important to consider the long-term effects on the kidney, including hypertension (37). Further work is necessary to distinguish the factors that influence the development of AKI from those exposures that do not result in AKI, but still disrupt normal nephrogenesis and result in premature CKD.

Within the gestational age cohorts, medication exposures were strongly associated with the development of early AKI. Although nephrotoxic antimicrobial medications represent a common and potentially modifiable risk factor for AKI, surprisingly, the neonates in the AWAKEN study exposed to nephrotoxic antimicrobials had an associated lower incidence of early AKI. This unexpected finding is paradoxic and likely explained by classification bias generated by the definition of the exposure: neonates had to receive the nephrotoxic medication before AKI diagnosis. This exposure definition allowed for patients with a rapidly rising creatinine or early reduction of urine output to fall into the category of “no nephrotoxic exposure.” Another statistical consideration to note is that these medications are ubiquitously used in the neonatal ICU. These medications are given to patients during sepsis evaluations, introducing the risk of confounding by indication. In AWAKEN, 69% of enrolled neonates received a nephrotoxic antimicrobial agent in the first week after birth before an AKI event—the highest exposure in the lowest gestational age group (84%). In the 22–28-week group, aminoglycosides were often administered every 36–48 hours, reducing the total number of days in which the medication was administered for the analysis, but not necessarily the effective exposure, and potentially introducing a misclassification bias (38,39). Despite the contradictory finding between nephrotoxins and early AKI, it is possible that nephrotoxic medications such as aminoglycosides are not the inciting factor for the development of early AKI. Although studies in neonatal humans and animals confirm aminoglycoside-related tubular dysfunction (38,40), it is possible that the burden of nephrotoxins must accumulate to manifest with kidney dysfunction later in the hospital course. This is supported by animal data where prenatal exposure to gentamicin not only reduces total nephron number, but also results in glomerulosclerosis as the animals age (41), suggesting that the effect of aminoglycosides during kidney development may manifest with adulthood CKD.

Other medications examined in the AWAKEN study included diuretics, methylxanthines, vasopressors, and NSAIDs, and each was associated with lower risk within the gestational age strata. Methylxanthines have been known to influence kidney function, increasing urine output and the excretion of sodium and other solutes (42–44), likely as an adenosine receptor antagonist. Our findings suggest that methylxanthines may be protective of the kidneys in all neonates, consistent with a subanalysis of the AWAKEN dataset including only preterm neonates exposed to caffeine (45), in addition to publications by Carmody and Cattarelli (46,47). NSAIDs are vasoconstrictive agents used to prevent intraventricular hemorrhage and treat patent ductus arteriosus. Previous clinical studies have shown an association between NSAID exposure and AKI (48,49) and animal models have shown that NSAIDs given to neonatal rodents reduce nephron number (50). Within the 22–28-week group, 36% received some NSAID in the first week after birth and NSAID exposure was associated with lower odds of AKI. However, we were unable to assess the indication or the dose of the NSAID.

The AWAKEN study included institutional-level practices in the detection of AKI. The method used to measure serum creatinine levels (Jaffe versus enzymatic reactions) did not affect the incidence of early AKI. The incidence of early AKI was significantly higher in neonates in children’s hospitals as compared with perinatal centers with and without surgical capabilities. The study also highlights that AKI is associated with the number of serum creatinine assessments. The diagnosis of AKI was made by serum creatinine more often than by urine output in the 22–28-week group. At many of the sites, creatinine could be included with the panel of electrolytes, allowing for more frequent monitoring without increasing the risk to induce anemia common in this population.

Despite the significant strengths of AWAKEN, the study has several limitations in addition to variable practices in kidney function monitoring. The potential for incomplete acquisition of the outcome of AKI and the small numbers in the gestational age strata influenced the decision not to create a risk cohort for model development and validation. It is important to recognize that the AWAKEN cohort comprises high-risk neonates, not all neonates in the NICU, and we contend that monitoring practices in these high-risk neonates need to be standardized before the development of prediction models. The inclusion of only the high-risk neonates may lead to factors associated with a lower risk of AKI that seem implausible, such as multiple gestations or the paradoxic association with nephrotoxic antimicrobials. Therapies for hyperbilirubinemia and indications for antibiotics were unavailable in the AWAKEN dataset.

Neonatal AKI within the first week after birth is associated with poor short-term outcomes. Prevention, vigilant monitoring, and early detection are the hallmarks of optimal management of AKI (51). AWAKEN demonstrates a number of specific risk factors that should serve as “red flags” for clinicians at the initiation of their NICU course: outborn delivery, resuscitation with epinephrine, surgical need, hyperbilirubinemia, and inborn errors of metabolism, and daily kidney function monitoring is warranted. Future directions in AKI management need to focus on risk stratification of patients.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the outstanding work of the following clinical research personnel and colleagues for their involvement in Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates (AWAKEN): Ariana Aimani, Ana Palijan, Michael Pizzi—Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Julia Wrona—University of Colorado, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado; Melissa Bowman—University of Rochester, Rochester, New York; Teresa Cano, Marta G. Galarza, Wendy Glaberson, Denisse Cristina Pareja Valarezo—Holtz Children’s Hospital, University of Miami, Miami, Florida; Sarah Cashman, Madeleine Stead—University of Iowa Children’s Hospital, Iowa City, Iowa; Jonathan Davis, Julie Nicoletta—Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; Alanna DeMello—British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Lynn Dill, Emma Perez-Costas—University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama; Ellen Guthrie—MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio; Nicholas L. Harris, Susan M. Hieber—C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Katherine Huang, Rosa Waters—University of Virginia Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, Virginia; Judd Jacobs, Tara Terrell—Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Nilima Jawale—Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York; Emily Kane—Australian National University, Canberra, Australia; Patricia Mele—Stony Brook Children’s Hospital, Stony Brook, New York; Charity Njoku, Tennille Paulsen, Sadia Zubair—Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; Emily Pao—University of Washington, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington; Becky Selman, Michele Spear—University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Melissa Vega—The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York; and Leslie Walther—Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Center for Acute Care Nephrology provided funding to create and maintain the AWAKEN Medidata Rave electronic database. The Pediatric and Infant Center for Acute Nephrology (PICAN) provided support for web meetings, for the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative steering committee annual meeting at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), as well as support for some of the AWAKEN investigators at UAB (D.A., L.B., and R.G.). PICAN is part of the Department of Pediatrics at UAB, and is funded by Children’s of Alabama Hospital, the Department of Pediatrics, UAB School of Medicine, and UAB’s Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (National Institutes of Health [NIH] grant UL1TR001417). The AWAKEN study was supported at the University of New Mexico by the Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH grant UL1TR001449).

We provide here an additional list of other author’s commitments and funding sources that are not directly related to this study: J.R.C. is a co-owner of Sindri Technologies, LLC. She receives funding from the NIH National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; R01DK110622, R01DK111861, P50DK096373). D.A. serves on the speaker board for Baxter and the AKI Foundation (Cincinnati, OH); he also receives grant funding for studies not related to this manuscript from Octapharma AG (Switzerland), Otsuka Pharmaceuticals (MD), and the NIH NIDDK (R01 DK103608).

J.R.C. and A.L.K. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, collected data, aided the data analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript. L.B. and R.G. completed the data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to the drafting and revising of the manuscript. D.A. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, aided in data analysis, and contributed to the revising of the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. P.D.B., C.D., M.F., J.G., S.H., S.I., A.M., R.K.O., S.R., C.J.R., M.R., S.S., A.S., and M.S. contributed to the study design, collecting or supervising the collection of data, and revising the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The following Neonatal Kidney Collaborative members are nonauthor contributors and served as collaborators and site investigators for the AWAKEN study and deserve a PubMed citation. They collaborated in protocol development and review, local IRB submission, and data collection and participated in drafting or review of the manuscript: Namasivayam Ambalavanan—Department of Pediatrics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama. David T. Selewski, S.S.—C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Carolyn L Abitbol, Marissa DeFreitas, Shahnaz Duara—Holtz Children’s Hospital, University of Miami, Miami, Florida. Ronnie Guillet, Erin Rademacher—Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester, Rochester, New York. Maroun J. Mhanna, Rupesh Raina, Deepak Kumar—MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. Ayse Akcan Arikan—Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas. Stuart L. Goldstein, Amy T. Nathan—Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio. Juan C. Kupferman, Alok Bhutada—Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York. Elizabeth Bonachea, John Mahan, Arwa Nada—Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio. Jennifer Jetton, Tarah T. Colaizy, Jonathan M. Klein—University of Iowa Children’s Hospital, Iowa City, Iowa. F. Sessions Cole, T. Keefe Davis—Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri. Joshua Dower, Lawrence Milner—Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts. Kimberly Reidy, Frederick J. Kaskel—The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York. Katja M. Gist—University of Colorado, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado. Mina H. Hanna—University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky. Craig S. Wong, Catherine Joseph, Tara DuPont, Amy Staples—University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Surender Khokhar—Apollo Cradle, Gurgaon, Haryana, India. Sofia Perazzo, Patricio E. Ray—Children’s National Medical Center, George Washington University School of Medicine and the Health Sciences, Washington DC. Cherry Mammen, Anne Synnes—British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Pia Wintermark, Michael Zappitelli—Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Sidharth K. Sethi—Kidney and Urology Institute, Medanta, The Medicity, Gurgaon, India. Sanjay Wazir—Neonatology, Cloudnine Hospital, Gurgaon, Haryana, India. Smriti Rohatgi—Medanta, The Medicity, Gurgaon, Haryana, India. Danielle E. Soranno—University of Colorado, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, Colorado. Aftab S. Chishti—University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky. Robert Woroniecki, Shanty Sridhar—Stony Brook School of Medicine, Stony Brook, New York. Jonathan R. Swanson—University of Virginia Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number: Assessment of Worldwide AKI Epidemiology in Neonates (AWAKEN), NCT02443389

A complete list of nonauthor contributors appears at the end of this article.

See related editorial, “Increasing Awareness of Early Risk of AKI in Neonates,” on pages 172–174.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Namasivayam Ambalavanan, David T. Selewski, Jeffery Fletcher, Carolyn L Abitbol, Ronnie Guillet, Marissa DeFreitas, Shahnaz Duara, Erin Rademacher, Maroun J. Mhanna, Rupesh Raina, Deepak Kumar, Ayse Akcan Arikan, Stuart L. Goldstein, Amy T. Nathan, Juan C. Kupferman, Alok Bhutada, Elizabeth Bonachea, John Mahan, Arwa Nada, Jennifer Jetton, Tarah T. Colaizy, Jonathan M. Klein, F. Sessions Cole, T. Keefe Davis, Joshua Dower, Lawrence Milner, Kimberly Reidy, Frederick J. Kaskel, Katja M. Gist, Mina H. Hanna, Craig S. Wong, Catherine Joseph, Tara DuPont, Amy Staples, Surender Khokhar, Sofia Perazzo, Patricio E. Ray, Cherry Mammen, Anne Synnes, Pia Wintermark, Michael Zappitelli, Sidharth K. Sethi, Sanjay Wazir, Smriti Rohatgi, Danielle E. Soranno, Aftab S. Chishti, Robert Woroniecki, Jonathan R. Swanson, and Shanty Sridhar

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.03670318/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1: Definition of AKI by serum creatinine and urine output.

Supplemental Table 2. Classification used to describe congenital kidney anomalies.

Supplemental Table 3. Medications associated with neonatal AKI captured in data collection separated into categories.

Supplemental Table 4. Prevalence of early AKI in the overall cohort and by gestational age cohorts with frequency of creatinine measurements, type, and country of center.

Supplemental Figure 1. Correlation of prevalence of early AKI and frequency of creatinine monitoring by individual site and gestational age cohorts (22–28; 29–35; ≥36 weeks).

Supplemental Figure 2. Factors that are associated with odds of AKI by gestational age group.

References

- 1.Blinder JJ, Asaro LA, Wypij D, Selewski DT, Agus MSD, Gaies M, Ferguson MA: Acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery: A secondary analysis of the safe pediatric euglycemia after cardiac surgery trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 18: 638–646, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadepalli SK, Selewski DT, Drongowski RA, Mychaliska GB: Acute kidney injury in congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal life support: An insidious problem. J Pediatr Surg 46: 630–635, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur S, Jain S, Saha A, Chawla D, Parmar VR, Basu S, Kaur J: Evaluation of glomerular and tubular renal function in neonates with birth asphyxia. Ann Trop Paediatr 31: 129–134, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koralkar R, Ambalavanan N, Levitan EB, McGwin G, Goldstein S, Askenazi D: Acute kidney injury reduces survival in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Res 69: 354–358, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar S, Askenazi DJ, Jordan BK, Bhagat I, Bapuraj JR, Dechert RE, Selewski DT: Relationship between acute kidney injury and brain MRI findings in asphyxiated newborns after therapeutic hypothermia. Pediatr Res 75: 431–435, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selewski DT, Jordan BK, Askenazi DJ, Dechert RE, Sarkar S: Acute kidney injury in asphyxiated newborns treated with therapeutic hypothermia. J Pediatr 162: 725–729.e1, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Rhone ET, Charlton JR: Recognition and reporting of AKI in very low birth weight infants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2036–2043, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jetton JG, Guillet R, Askenazi DJ, Dill L, Jacobs J, Kent AL, Selewski DT, Abitbol CL, Kaskel FJ, Mhanna MJ, Ambalavanan N, Charlton JR; Neonatal Kidney Collaborative : Assessment of worldwide acute kidney injury epidemiology in neonates: Design of a retrospective cohort study. Front Pediatr 4: 68, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jetton JG, Boohaker LJ, Sethi SK, Wazir S, Rohatgi S, Soranno DE, Chishti AS, Woroniecki R, Mammen C, Swanson JR, Sridhar S, Wong CS, Kupferman JC, Griffin RL, Askenazi DJ; Neonatal Kidney Collaborative (NKC) : Incidence and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury (AWAKEN): A multicentre, multinational, observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 1: 184–194, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Askenazi DJ, Koralkar R, Hundley HE, Montesanti A, Patil N, Ambalavanan N: Fluid overload and mortality are associated with acute kidney injury in sick near-term/term neonate. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 661–666, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jetton JG, Askenazi DJ: Acute kidney injury in the neonate. Clin Perinatol 41: 487–502, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG: Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003311, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellum JA, Lameire N; KDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group : Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: A KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 17: 204, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaddourah A, Basu RK, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL; AWARE Investigators : Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill children and young adults. N Engl J Med 376: 11–20, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzzolin L, Fanos V, Pinna B, di Marzio M, Perin M, Tramontozzi P, Tonetto P, Cataldi L: Postnatal renal function in preterm newborns: A role of diseases, drugs and therapeutic interventions. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 931–938, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cataldi L, Leone R, Moretti U, De Mitri B, Fanos V, Ruggeri L, Sabatino G, Torcasio F, Zanardo V, Attardo G, Riccobene F, Martano C, Benini D, Cuzzolin L: Potential risk factors for the development of acute renal failure in preterm newborn infants: A case-control study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 90: F514–F519, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolat F, Comert S, Bolat G, Kucuk O, Can E, Bulbul A, Uslu HS, Nuhoglu A: Acute kidney injury in a single neonatal intensive care unit in Turkey. World J Pediatr 9: 323–329, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathur NB, Agarwal HS, Maria A: Acute renal failure in neonatal sepsis. Indian J Pediatr 73: 499–502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruel A, Rozé JC, Flamant C, Simeoni U, Roussey-Kesler G, Allain-Launay E: Critical serum creatinine values in very preterm newborns. PLoS One 8: e84892, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein SL, Mottes T, Simpson K, Barclay C, Muething S, Haslam DB, Kirkendall ES: A sustained quality improvement program reduces nephrotoxic medication-associated acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 90: 212–221, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harer MW, Pope CF, Conaway MR, Charlton JR: Follow-up of Acute kidney injury in Neonates during Childhood Years (FANCY): A prospective cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 1067–1076, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marlow N, Bennett C, Draper ES, Hennessy EM, Morgan AS, Costeloe KL: Perinatal outcomes for extremely preterm babies in relation to place of birth in England: The EPICure 2 study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 99: F181–F188, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellinger M, Haag K, Burckhardt G, Gerok W, Knauf H: Sulfated bile acids inhibit Na(+)-H+ antiport in human kidney brush-border membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol 258: F986–F991, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benders MJ, van Bel F, van de Bor M: The effect of phototherapy on renal blood flow velocity in preterm infants. Biol Neonate 73: 228–234, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennery PA, Seidman DS, Stevenson DK: Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. N Engl J Med 344: 581–590, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel J, Walayat S, Kalva N, Palmer-Hill S, Dhillon S: Bile cast nephropathy: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 22: 6328–6334, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. NIH Consensus Development Panel on the Effect of Corticosteroids for Fetal Maturation on Perinatal Outcomes. JAMA 273: 413–418, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.al-Dahan J, Stimmler L, Chantler C, Haycock GB: The effect of antenatal dexamethasone administration on glomerular filtration rate and renal sodium excretion in premature infants. Pediatr Nephrol 1: 131–135, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ervin MG, Seidner SR, Leland MM, Ikegami M, Jobe AH: Direct fetal glucocorticoid treatment alters postnatal adaptation in premature newborn baboons. Am J Physiol 274: R1169–R1176, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stonestreet BS, Hansen NB, Laptook AR, Oh W: Glucocorticoid accelerates renal functional maturation in fetal lambs. Early Hum Dev 8: 331–341, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodic M, May CN, Wintour EM, Coghlan JP: An early prenatal exposure to excess glucocorticoid leads to hypertensive offspring in sheep. Clin Sci (Lond) 94: 149–155, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dodic M, Hantzis V, Duncan J, Rees S, Koukoulas I, Johnson K, Wintour EM, Moritz K: Programming effects of short prenatal exposure to cortisol. FASEB J 16: 1017–1026, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dodic M, Abouantoun T, O’Connor A, Wintour EM, Moritz KM: Programming effects of short prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in sheep. Hypertension 40: 729–734, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Figueroa JP, Rose JC, Massmann GA, Zhang J, Acuña G: Alterations in fetal kidney development and elevations in arterial blood pressure in young adult sheep after clinical doses of antenatal glucocorticoids. Pediatr Res 58: 510–515, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moritz KM, Johnson K, Douglas-Denton R, Wintour EM, Dodic M: Maternal glucocorticoid treatment programs alterations in the renin-angiotensin system of the ovine fetal kidney. Endocrinology 143: 4455–4463, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wintour EM, Moritz KM, Johnson K, Ricardo S, Samuel CS, Dodic M: Reduced nephron number in adult sheep, hypertensive as a result of prenatal glucocorticoid treatment. J Physiol 549: 929–935, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geelhoed JJ, Fraser A, Tilling K, Benfield L, Davey Smith G, Sattar N, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA: Preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are associated with childhood blood pressure independently of family adiposity measures: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Circulation 122: 1192–1199, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giapros VI, Cholevas VI, Andronikou SK: Acute effects of gentamicin on urinary electrolyte excretion in neonates. Pediatr Nephrol 19: 322–325, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vieux R, Fresson J, Guillemin F, Hascoet JM: Perinatal drug exposure and renal function in very preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 96: F290–F295, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent AL, Douglas-Denton R, Shadbolt B, Dahlstrom JE, Maxwell LE, Koina ME, Falk MC, Willenborg D, Bertram JF: Indomethacin, ibuprofen and gentamicin administered during late stages of glomerulogenesis do not reduce glomerular number at 14 days of age in the neonatal rat. Pediatr Nephrol 24: 1143–1149, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilbert T, Lelievre-Pegorier M, Malienou R, Meulemans A, Merlet-Benichou C: Effects of prenatal and postnatal exposure to gentamicin on renal differentiation in the rat. Toxicology 43: 301–313, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gouyon JB, Guignard JP: Adenosine in the immature kidney. Dev Pharmacol Ther 13: 113–119, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gouyon JB, Guignard JP: Renal effects of theophylline and caffeine in newborn rabbits. Pediatr Res 21: 615–618, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gouyon JB, Guignard JP: Theophylline prevents the hypoxemia-induced renal hemodynamic changes in rabbits. Kidney Int 33: 1078–1083, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harer MW, Askenazi DJ, Boohaker LJ, Carmody JB, Griffin RL, Guillet R, Selewski DT, Swanson JR, Charlton JR; Neonatal Kidney Collaborative (NKC) : Association between early caffeine citrate administration and risk of acute kidney injury in preterm neonates: Results from the AWAKEN study. JAMA Pediatr 172: e180322, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmody JB, Harer MW, Denotti AR, Swanson JR, Charlton JR: Caffeine exposure and risk of acute kidney injury in a retrospective cohort of very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr 172: 63–68.e1, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cattarelli D, Spandrio M, Gasparoni A, Bottino R, Offer C, Chirico G: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of the effect of theophylline in prevention of vasomotor nephropathy in very preterm neonates with respiratory distress syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 91: F80–F84, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhone ET, Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Charlton JR: Nephrotoxic medication exposure in very low birth weight infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 27: 1485–1490, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akima S, Kent A, Reynolds GJ, Gallagher M, Falk MC: Indomethacin and renal impairment in neonates. Pediatr Nephrol 19: 490–493, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kent AL, Koina ME, Gubhaju L, Cullen-McEwen LA, Bertram JF, Lynnhtun J, Shadbolt B, Falk MC, Dahlstrom JE: Indomethacin administered early in the postnatal period results in reduced glomerular number in the adult rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307: F1105–F1110, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nada A, Bonachea EM, Askenazi DJ: Acute kidney injury in the fetus and neonate. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 22: 90–97, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.