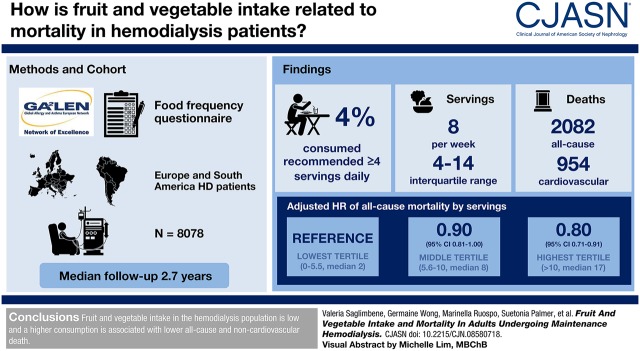

Visual Abstract

Keywords: nutrition, mortality, hemodialysis, clinical epidemiology, clinical nephrology, Epidemiology and outcomes, ESRD, mortality risk, risk factors, survival, Vegetables, Fruit, Asthma, Hyperkalemia, Diet, Risk, Hypersensitivity, Proportional Hazards Models, renal dialysis, Cardiovascular Diseases, Surveys and Questionnaires

Abstract

Background and objectives

Higher fruit and vegetable intake is associated with lower cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population. It is unclear whether this association occurs in patients on hemodialysis, in whom high fruit and vegetable intake is generally discouraged because of a potential risk of hyperkalemia. We aimed to evaluate the association between fruit and vegetable intake and mortality in hemodialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Fruit and vegetable intake was ascertained by the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network food frequency questionnaire within the Dietary Intake, Death and Hospitalization in Adults with ESKD Treated with Hemodialysis study, a multinational cohort study of 9757 adults on hemodialysis, of whom 8078 (83%) had analyzable dietary data. Adjusted Cox regression analyses clustered by country were conducted to evaluate the association between tertiles of fruit and vegetable intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality. Estimates were calculated as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

Results

During a median follow up of 2.7 years (18,586 person-years), there were 2082 deaths (954 cardiovascular). The median (interquartile range) number of servings of fruit and vegetables was 8 (4–14) per week; only 4% of the study population consumed at least four servings per day as recommended in the general population. Compared with the lowest tertile of servings per week (0–5.5, median 2), the adjusted hazard ratios for the middle (5.6–10, median 8) and highest (>10, median 17) tertiles were 0.90 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.00) and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.91) for all-cause mortality, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.02) and 0.77 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.91) for noncardiovascular mortality and 0.95 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.11) and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.70 to 1.00) for cardiovascular mortality, respectively.

Conclusions

Fruit and vegetable intake in the hemodialysis population is low and a higher consumption is associated with lower all-cause and noncardiovascular death.

Introduction

People with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) experience premature mortality and a life expectancy of an average of 3–4 years once they commence dialysis (1). Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in this population, accounting for about 40% of deaths (1,2). Apart from kidney transplantation, no treatment or preventive strategies have consistently been shown to reduce mortality for people on long-term hemodialysis (3–7). Novel and effective interventions are needed.

A healthy diet including at least four to five servings of fruit and vegetables per day is widely recommended for the prevention of major chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer (8–10). Evidence from observational studies suggests an association between higher consumption of fruit and vegetables and a 10%–20% lower risk of all-cause mortality, largely driven by reducing cardiovascular mortality (11–13). Biologic constituents of fruit and vegetables (such as vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, micronutrients, and phytochemicals) may have additive and synergistic cardioprotective effects, including reducing oxidative stress and blood pressure, and improving the lipoprotein profile and insulin sensitivity (14,15).

Emerging evidence suggests that a diet rich in fruit and vegetables may be associated with lower mortality among adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD). A recent systematic review of observational studies showed that dietary patterns higher in fruit and vegetables were associated with 30% lower all-cause mortality among patients with mild to moderate CKD (16). In patients with ESKD treated with hemodialysis, a high consumption of these foods is generally discouraged to prevent hyperkalemia (17). However, the effects of fruit and vegetables on mortality in this population have not been examined. In this large-scale, multinational, prospective, cohort study, we evaluated the association of fruit and vegetable intake with all-cause, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality among adults treated with hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This analysis was conducted as part of the Dietary Intake, Death and Hospitalization in Adults with ESKD Treated with Hemodialysis (DIET-HD) study, a multinational, prospective, cohort study conducted in 11 countries. The study design has been described elsewhere (18). This study is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology guidelines (19).

Participants

The DIET-HD study was conducted in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey) and South America (Argentina). Between January 2014 and January 2015, consecutive adults receiving hemodialysis at selected clinics within a private dialysis provider network were included. Eligible participants were treated with long-term hemodialysis (at least 90 days), were able to complete the food frequency questionnaire, had a life expectancy of at least 6 months, and were not scheduled for kidney transplantation within 6 months of recruitment. Relevant institutional ethics committees approved the study. Ethical approval details are reported in the published protocol. Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03125265NCT03125265. All participants provided written and informed consent before participation.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics including sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory and dialysis data within 1 month of enrolment were extracted from a centralized, routinely collected administrative database, coordinated by the dialysis provider, using data linkage with the study-specific database. Data were provided by the participants’ treating clinicians using medical records for laboratory data (e.g., hemoglobin, phosphorus, calcium, potassium) and clinical characteristics (e.g., time on dialysis, comorbidities) and participants’ self-reported surveys for lifestyle characteristics. In particular, patients were asked how many times they exercised during the week (never, irregularly, once a week, more than once a week, or daily); whether they were current smokers, former smokers (stopped <1 year ago, 1–5 years ago, or >5 years ago) or they had never smoked; what their highest level of education was (none, primary, secondary, or university degree); and whether they had a life partner (windowed, divorced, separated, or single).

Dietary Assessment

At baseline, each participant’s diet during the last 12 months was ascertained using the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) food frequency questionnaire, designed to assess dietary intake across countries using a single, common and standardized instrument (20). The food frequency questionnaire was self-reported during a routine hemodialysis treatment. Data from the food frequency questionnaire were entered into an electronic database using optical character recognition, and linked to the centralized administrative database. Standard food portion sizes were used to calculate daily food intake (grams) following the recommendations from the United Kingdom’s Food Standards Agency (21). Macro- and micronutrient intakes were derived using the latest available McCance and Widdowson’s Food Composition Tables (22).

Fruit and vegetable consumption was assessed by asking participants the following two questions: (1) “How often did you eat any fresh fruit during the previous year?” and (2) “How often did you eat any vegetables (excluding potatoes) during the previous year?” Patients could choose among eight predefined responses (ranging from rarely or never to four or more times per day). These responses were converted into average servings per week. Fruit and vegetable intakes were considered both as combined and separate intakes. Fruit juices were excluded from the total fruit intake because of the different content of fiber and sugar; legumes and potatoes were excluded from the total vegetable intake because of the different carbohydrate and energy compositions (10,23).

Outcomes

All-cause and cause-specific mortality outcomes were obtained from the centralized administrative database using data linkage. The outcomes were all-cause, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular mortality. Deaths were attributed as due to cardiovascular causes when they were a sudden death or as due to acute myocardial infarction, pericarditis, atherosclerotic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, valvular heart disease, pulmonary edema, congestive cardiac failure, cerebrovascular accident including intracranial hemorrhage, ischemic brain damage/anoxic encephalopathy, or hemorrhage from ruptured vascular aneurysm. Noncardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to infection, cancer, liver disease, gastrointestinal disease, metabolic disease, or other/unknown causes. All-cause mortality was death from any cause. Mortality events had been prospectively reported by the participants’ treating clinicians, without knowledge of dietary intake, up to June 27, 2017. The causes of death were obtained from the death certificates and recorded according to the United States coding for the ESKD population (24,25).

Statistical Analyses

Participants were included in the analyses if their food frequency questionnaire had <20% missing answers, plausible responses (total energy intake within 3 SD from the log-transformed mean); complete data on fruit intake, vegetable intake or both; and included a valid participant identification code to enable data linkages. Patients with missing data for either fruit or vegetables were deemed to have zero intakes for either fruit or vegetables in the model that considered both fruit and vegetables as a joint exposure.Baseline characteristics were calculated as mean and SD or median and interquartile range, as appropriate to their distribution for continuous variables, and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Restricted cubic splines were used to determine the linearity between fruit and vegetable servings and mortality (26). Person-time for each participant was calculated from the date of the food frequency questionnaire administration to the date of death (all-cause, cardiovascular, and noncardiovascular) or censoring for transfer outside the network, kidney transplantation, transfer to peritoneal dialysis, withdrawal from dialysis, recovery of kidney function, being temporary out of the dialysis network, lost to follow-up for other reasons, or end of the follow-up period. In addition, in analyses of cardiovascular mortality, participants who died from noncardiovascular causes were censored. Participants who died from cardiovascular causes were censored in the analysis of noncardiovascular death. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were fitted using a random effects (frailty) model to account for clustering of mortality risk within countries. The weekly servings of fruit and vegetables, combined and separately, were modeled as continuous variables (one serving increase) and categorized into tertiles.Estimates of association were calculated as hazard ratios (HRs) together with the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), using the lowest tertile of intake as reference category. The proportional hazards assumption in Cox models was assessed by testing an interaction term between the log (person-time) and the covariates in the multivariable model. Effect modifications of the association between servings of fruit and vegetables and mortality by age and sex were tested using interaction terms in the multivariable model. Backward elimination was used to build three separate multivariable models, one for each mortality outcome, selecting those variables (aside from energy intake, smoking history, and physical activity, which were clinically relevant variables specified a priori) that were significantly associated with mortality (P<0.05) or had a clinically meaningful effect on the HR for mortality (≥10%). Accordingly, all analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking (current or former versus never), daily physical activity, prior myocardial infarction, vascular access type (fistula or graft/catheter), body mass index (categories according to World Health Organization), serum albumin (tertiles), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (quartiles), hemoglobin, and total energy intake (1000 kcal/d increase). In addition to these variables, analyses of all-cause mortality were adjusted for education, life partner, primary underlying kidney disease, being waitlisted for transplant, serum phosphorus and calcium, time on dialysis, and Kt/V. Analyses of cardiovascular mortality were adjusted for education (secondary versus none/primary), diabetes, and serum phosphorus and calcium. Analyses of noncardiovascular mortality were adjusted for the underlying kidney disease and being waitlisted for transplant. On the basis of the criteria mentioned above, other dietary components (including servings per week of legumes, cereals, dairy, white meat, red and processed meat, fish, and sweets; grams per day of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, alcohol, cereal fiber, and sugar; and the Mediterranean diet score [27], computed as indicative of a healthier whole diet) were not considered as confounders and therefore were not retained in the final models. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of proteins found in fruit and vegetables (1 g/d increase), using further adjustment for this intake in a separate model. All of the analyses of fruit servings were adjusted for vegetable servings and vice versa. For each categorical variable, an extra category was included for missing data (data were missing at random) in the multivariable model, when necessary (smoking, daily physical activity, diabetes, myocardial infarction, education, life partner, underlying kidney disease, body mass index, serum albumin, and being waitlisted for transplant). A complete-case analysis was also conducted including only those patients with complete data for covariates. Data for outcomes were complete for the analyzed cohort.

The potential effect of competing events (deaths from noncardiovascular mortality and kidney transplantation for the analysis of cardiovascular mortality; deaths from cardiovascular mortality and kidney transplantation for the analysis of noncardiovascular mortality; kidney transplantation for the analysis of all-cause mortality) was considered using a stratified proportional subdistribution hazard model.

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4. (2014; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

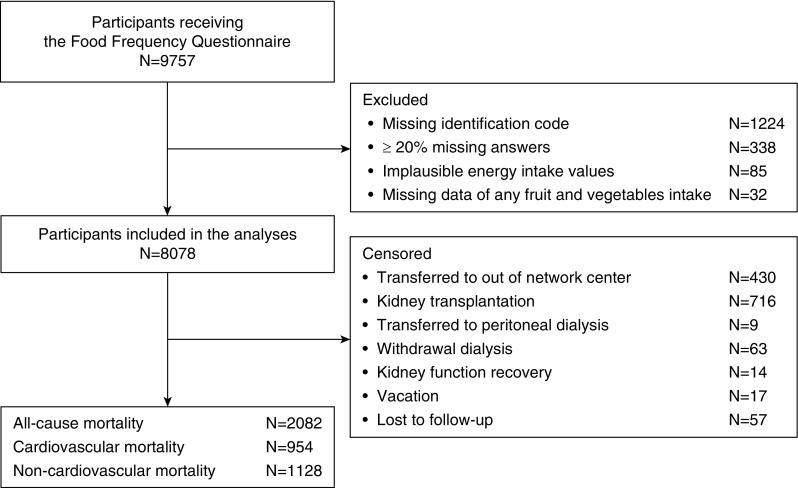

A total of 9757 patients on hemodialysis were enrolled in the study and completed the food frequency questionnaire. After excluding participants for whom the food frequency questionnaire contained an erroneous or missing identification code (13%), insufficient or implausible dietary responses (4%), or missing data for both any fruit and vegetable intake (0.3%), 8078 (83%) remained in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the participation process, resulting in the inclusion of 8078 participants in analyses, and all censoring details.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population overall and by tertiles of baseline combined intake of fruit and vegetables. The mean age of the cohort was 63 years (SD 15 years). Overall, 58% were men, 33% were former or current smokers, 15% engaged in daily physical activity, 32% had diabetes, 12% had experienced myocardial infarction, and 9% had experienced stroke. Participants had been treated with hemodialysis for a median of 3.6 years (interquartile range, 1.7–6.8 years).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the Dietary Intake, Death and Hospitalization in Adults with ESKD Treated with Hemodialysis (DIET-HD) study

| Variable | No. of Participants with Data | Overall, n=8078 | Fruit and Vegetable Intake, Servings per wk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5.5, n=2520 | 5.6–10, n=2958 | >10, n=2600 | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age, yr | 8078 | 63 (15) | 62 (15) | 63 (15) | 64 (15) |

| Men | 8078 | 4678 (58) | 1428 (57) | 1753 (59) | 1497 (58) |

| Life partner | 6069 | 4108 (68) | 1143 (67) | 1541 (68) | 1424 (68) |

| Secondary education | 6066 | 2689 (44) | 742 (42) | 1033 (46) | 914 (44) |

| Daily physical activity | 6175 | 930 (15) | 286 (16) | 355 (15) | 289 (14) |

| Waitlisted for transplant | 8062 | 1489 (18) | 511 (20) | 526 (18) | 452 (17) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Current or former smoker | 6256 | 2059 (33) | 585 (33) | 789 (34) | 685 (32) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 7870 | ||||

| Underweight, <18.5 | 365 (5) | 144 (6) | 122 (4) | 99 (4) | |

| Normal range, 18.5–24.9 | 3294 (42) | 1034 (42) | 1208 (42) | 1052 (42) | |

| Preobese, 25.0–29.9 | 2646 (34) | 822 (34) | 954 (33) | 870 (34) | |

| Obese, ≥30.0 | 1535 (20) | 450 (18) | 584 (20) | 501 (20) | |

| Hypertension | 7292 | 6196 (85) | 1763 (84) | 2311 (85) | 2122 (86) |

| Diabetes | 7255 | 2332 (32) | 610 (29) | 825 (30) | 887 (36) |

| Myocardial infarction | 7211 | 831 (11) | 249 (12) | 302 (11) | 280 (11) |

| Stroke | 7205 | 633 (9) | 172 (8) | 247 (9) | 214 (9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | 8078 | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–7) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (5–8) |

| Laboratory variables | |||||

| Albumin, g/dl | 6139 | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.4) |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 7837 | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.4) |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 7838 | 8.9 (0.7) | 8.9 (0.8) | 8.9 (0.7) | 9.0 (0.7) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 7837 | 11.1 (1.3) | 11.1 (1.3) | 11.1 (1.3) | 11.1 (1.3) |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 2353 | 5.0 (0.7) | 5.1 (0.7) | 5.0 (0.7) | 5.0 (0.7) |

| Dialysis characteristics | |||||

| Arteriovenous fistula | 8019 | 6452 (80) | 1998 (80) | 2363 (80) | 2091 (81) |

| Time on dialysis, yr | 8078 | 3.6 (1.7–6.8) | 3.8 (1.8–7.0) | 3.7 (1.7–7.0) | 3.4 (1.6–6.3) |

| Kt/V urea | 7786 | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.4) |

| Dietary intake, servings per wk | |||||

| Fruit | 7967 | 5.5 (1.0–7.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 5.5 (3.0–7.0) | 14.0 (7.0–14.0) |

| Vegetables | 7917 | 3.0 (1.0–5.5) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 3.0 (3.0–3.0) | 7.0 (5.5–7.0) |

| Legumes and nuts | 8078 | 1.0 (0.5–3.0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.5–3.0) | 1.0 (0.5–3.5) |

| Cereals | 8075 | 14.5 (8.0–18.5) | 11.0 (4.0–16.0) | 14.5 (8.0–18.0) | 16.5 (11.0–20.5) |

| Dairy | 8077 | 6.0 (2.0–10.0) | 3.0 (1.0–7.5) | 6.5 (3.0–10.0) | 7.5 (3.0–12.5) |

| Fish and white meat | 8074 | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 1.5 (0.5–3.5) | 3.0 (1.5–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.5) |

| Red meat and meat products | 8032 | 3.0 (0.5–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) | 3.0 (1.0–3.0) | 3.0 (1.0–5.5) |

| Sweets and sweetened drinks | 8078 | 14.0 (6.5–22.5) | 10.5 (4.5–19.0) | 14.5 (7.0–23.0) | 15.0 (7.5–25.5) |

| Total energy intake, kcal | 8078 | 2089 (1033) | 1740 (936) | 2064 (949) | 2457 (1090) |

Continuous data are expressed as mean (SD), median (25th, 75th quartile), or number (percentage). Body max index categories are defined according to the World Health Organization.

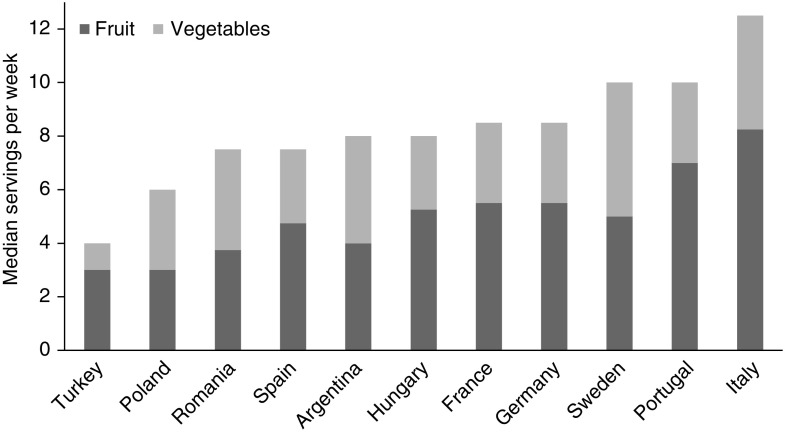

The observed combined median (interquartile range) intake of fruit and vegetables was 8.0 (4.0–14.0) servings per week. The separate median intakes of fruit and vegetables were 5.5 (1.0–7.0) and 3.0 (1.0–5.5) servings per week, respectively. The distribution of fruit and vegetable intake was similar across countries (Figure 2), and far below the recommended intake for the prevention of major chronic diseases in the general population (8–10) (only 4% of the whole cohort consumed at least four servings per day of these foods). The combined median servings of fruit and vegetables ranged from 4.0 (1.5–8.0) per week in participants from Turkey, to 12.5 (7.0–17.0) in participants from Italy (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Median intake of fruit and vegetables (servings per week) by country showing similar, and generally low, intake across all countries.

Participants in the highest tertile of combined fruit and vegetable intake (more than ten servings per week, median 17.0) were older, more likely to have diabetes, and had been treated with hemodialysis for a shorter time compared with those in the lowest (0–5.5, median 2.0) and middle (5.6–10.0, median 8.0) tertiles. In contrast, lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking and physical activity, and serum predialysis potassium levels were similar across tertiles of intake (Table 1).

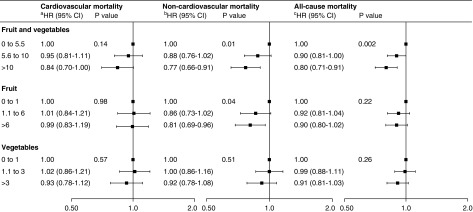

All-Cause Mortality

During a median follow up period of 2.7 years (18,586 person-years), 2082 participants died (Table 2), with an overall event rate of 24%–27% across the three tertiles. Compared with participants in the lowest tertile of combined fruit and vegetable weekly servings, the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality among those in the middle and highest tertiles were 0.90 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.00) and 0.80 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.91), respectively (P=0.002) (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 2) (5% absolute risk reduction with the highest intake). Compared with participants in the lowest tertile of fruit weekly servings (0–1.0), the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality among those in the middle (1.1–6.0) and highest (>6.0) tertiles were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.04) and 0.90 (95 CI, 0.80 to 1.02), respectively (P=0.22). Compared with participants in the lowest tertile of vegetable weekly servings (0–1.0), the adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality among those in the middle (1.1–3.0) and highest (>3.0) tertiles were 0.99 (95% CI, 0.88 to 1.11) and 0.91 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.03), respectively (P=0.26) (Figure 3). Results were similar when we additionally controlled for protein intake from fruit and vegetables (Supplemental Table 3). Similar findings were observed when accounting for the competing risk of kidney transplantation and within a complete-case analysis (including 3479 and 3360 participants in the analysis of combined and separate fruit and vegetable intakes, respectively) (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2.

Cause-specific death by tertiles of fruit and vegetable intake

| Cause of death | Fruit and Vegetable Intake, Servings per wk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0–5.5 | 5.6–10 | >10 | |||||

| N (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 Person-yr | N (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 Person-yr | N (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 Person-yr | N (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 Person-yr | |

| Cardiovascular | 954 (46) | 51 | 323 (48) | 57 | 356 (46) | 52 | 275 (44) | 46 |

| Infection | 361 (17) | 20 | 114 (17) | 20 | 133 (17) | 20 | 114 (18) | 19 |

| Cancer | 158 (8) | 9 | 48 (7) | 8 | 65 (8) | 10 | 45 (7) | 7 |

| Gastrointestinal | 72 (3) | 4 | 24 (3) | 4 | 30 (4) | 4 | 18 (3) | 3 |

| Liver disease | 24 (1) | 1 | 4 (0.6) | 1 | 12 (2) | 2 | 8 (1) | 1 |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | 24 (1) | 1 | 8 (1) | 1 | 10 (1) | 1 | 6 (1) | 1 |

| Metabolic | 7 (0.3) | 0.4 | 3 (0.4) | 1 | — | — | 4 (0.6) | 1 |

| Endocrine | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Other | 316 (15) | 17 | 102 (15) | 18 | 110 (14) | 16 | 104 (16) | 17 |

| Unknown | 166 (8) | 9 | 53 (8) | 9 | 56 (7) | 8 | 57 (9) | 9 |

| All-cause | 2082 (26) | 112 | 679 (27) | 120 | 772 (26) | 114 | 631 (24) | 105 |

Other causes of death include hemorrhage from vascular access or dialysis circuit (n=2), other hemorrhage (n=6), mesenteric infarction/ischemic bowel (n=22), bone marrow depression (n=2), cachexia/failure to thrive (n=60), dementia including dialysis dementia and Alzheimer (n=9), seizures (n=1), chronic obstructive lung disease (n=14), complications of surgery (n=18), air embolism (n=8), accident unrelated to treatment (n=16), suicide (n=2), and other unspecified (n=156). —, None.

Figure 3.

Adjusted mortality hazard ratios (HRs) (95% CIs) by tertiles of fruit and vegetable intake (servings per week) showing an association between higher combined intake of fruit and vegetables and lower all-cause mortality largely driven by noncardiovascular causes. HR estimates for one serving per week increase of combined fruit and vegetable intake are 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.00; P=0.05), 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98 to 0.99; P=0.001), and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98 to 0.99; P≤0.001) for cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, and all-cause mortality, respectively. HR estimates for one serving per week increase of fruit intake are 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97 to 1.00; P=0.13), 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97 to 1.00; P=0.03), and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.00; P=0.01) for cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, and all-cause mortality, respectively. HR estimates for one serving per week increase of vegetable intake are 1.00 (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.02; P=0.63), 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97 to 1.00; P=0.12), and 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98 to 1.00; P=0.13) for cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, and all-cause mortality, respectively. All analyses are adjusted for country (random effect), age, sex, smoking (current or former versus never), daily physical activity, myocardial infarction, vascular access type (fistula versus graft/catheter), body mass index (categories according to World Health Organization), albumin (tertiles), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (quartiles), hemoglobin, and energy intake (1000 kcal/d increase). Analyses for fruit are adjusted for vegetables and vice versa. aAdditionally adjusted for education (secondary versus none/primary), diabetes, phosphorus, and calcium. bAdditionally adjusted for underlying kidney disease and being waitlisted for transplant. cAdditionally adjusted for education (secondary versus none/primary), life partner, underlying kidney disease, being waitlisted for transplant, phosphorus, calcium, time on dialysis, and Kt/V.

Cardiovascular Mortality

There were 954 cardiovascular deaths (Table 2), with an overall event rate of 11%–13% across the three tertiles. The adjusted HRs for cardiovascular mortality were 0.95 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.11) and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.70 to 1.00) for participants in the middle and highest tertiles of combined fruit and vegetable intake, respectively (P=0.14) (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 2). Servings per week of fruit (adjusted HRs for middle and highest tertiles of weekly servings: 1.01 [95% CI, 0.84 to 1.21] and 0.99 [95% CI, 0.83 to 1.19]; P=0.98) or vegetables (1.02 [95% CI, 0.86 to 1.21] and 0.93 [95% CI, 0.78 to 1.12]; P=0.57) were not significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality (Figure 3). Results were similar when we additionally controlled for protein intake from fruit and vegetables (Supplemental Table 3). Similar findings were observed when accounting for the competing risk of noncardiovascular mortality and kidney transplantation and within complete-case analyses (including 3904 and 3768 patients in the analysis of combined and separate fruit and vegetable intakes, respectively) (Supplemental Table 5).

Noncardiovascular Mortality

There were 1128 noncardiovascular deaths (Table 2), with an overall event rate of 14% across the three tertiles. The adjusted HRs for noncardiovascular mortality were 0.88 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.02) and 0.77 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.91; P=0.01) for participants in the middle and highest tertiles of combined fruit and vegetable intake, respectively (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 2) (3% absolute risk reduction with the highest intake). Fruit intake was inversely associated with noncardiovascular mortality (0.86 [95% CI, 0.73 to 1.02] and 0.81 [95% CI, 0.69 to 0.96]; P=0.04), whereas no significant association was observed for vegetable intake (1.00 [95% CI, 0.86 to 1.16] and 0.92 [95% CI, 0.78 to 1.08]; P=0.51) (Figure 3). Results were similar when we additionally controlled for protein intake from fruit and vegetables (Supplemental Table 3). Similar findings were observed when accounting for the competing risk of cardiovascular mortality and kidney transplantation and within complete-case analyses (including 4173 and 4027 patients in the analysis of combined and separate fruit and vegetable intakes, respectively) (Supplemental Table 6).

Discussion

In this study involving 8078 patients on hemodialysis followed for nearly 3 years, during which 2082 died (26%), the median combined intake of fruit and vegetables was below ten servings each week. This intake was substantially lower than the recommended value for prevention of major chronic diseases in the general population and was similar across all 11 countries in Europe and South America participating in the study. Compared with an intake of about two servings per week, increasing consumption of fruit and vegetables to approximately 17 servings each week (2–3 per day) was associated with a 20% lower risk of all-cause mortality (5% absolute risk reduction) and death due to noncardiovascular causes (3% absolute risk reduction). Evidence for an association between fruit and vegetable consumption with cardiovascular death was weaker and included the possibility of no effect.The burden of accelerated cardiovascular disease leading to complications and premature death in ESKD is substantially higher than for the general population. Accumulating evidence suggests that an equally increased risk of noncardiovascular mortality contributes to the observed excess mortality among patients on hemodialysis (2,28,29). Infection and cancer are the leading causes of noncardiovascular death in hemodialysis. Higher fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with reduced cancer mortality in the general population (12). Therefore, it is plausible that a higher frequency of fruit and vegetable intake may prevent noncardiovascular mortality in patients on hemodialysis by reducing the risk of cancer death. However, the number of cancer deaths in our study was insufficient to test this specific hypothesis.Traditional nutritional research within the hemodialysis setting has been focused on individual dietary nutrients, including protein, phosphate, sodium, and potassium, rather than whole foods and dietary patterns (16,30). Accordingly, no previous study has evaluated the effect of fruit and vegetables on mortality in patients on hemodialysis. However, our finding that lower mortality is associated with greater consumption of fruit and vegetables is consistent with research conducted among the general population (11,12). Particularly, our results are concordant with those from a recent large international study (the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology study) reporting a significant inverse association between fruit and vegetable intake and noncardiovascular mortality (31).Notably, fruit and vegetable consumption observed in this multinational hemodialysis cohort was substantially below the recommended intake for the prevention of major chronic diseases in the general population. This finding is expected when considering usual dietary recommendations for patients with ESKD, for whom consumption of fruit and vegetables is generally discouraged on the basis of a theoretical risk of exacerbation of hyperkalemia (17). In some dialysis units, potassium-binding resins are used to control hyperkalemia, allowing a more liberal intake of fruit and vegetables. However, these agents have shown poor adherence because of gastrointestinal intolerability and no clear association with mortality (32,33). Interestingly, patients treated with hemodialysis seem to be adherent to the recommended guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumptions. However, our findings that a higher consumption of these foods is associated with good outcomes calls these recommendations into questions, especially given the paucity of evidence showing a direct relationship between dietary intake of potassium and serum levels status (34,35).

Our findings suggest that well meaning guidance to limit fruit and vegetable intake to prevent higher dietary potassium load may deprive patients on hemodialysis of the potential benefits of these foods. As the evidentiary basis for dietary fruit and vegetable consumption is currently reliant on nonrandomized data, intervention trials of fruit and vegetable intake are needed to support dietary recommendations for patients on hemodialysis. Future studies exploring the potential benefits of a whole-diet approach in the hemodialysis setting are also warranted.Our study has important strengths. The DIET-HD study is a large, multinational study conducted in patients on hemodialysis that assessed the effect of diet as a potential determinant of health, which has been identified as a research priority for patients with CKD, their caregivers, and health care professionals (36). The study included detailed measurements of dietary components and demographic and lifestyle variables, enabling adjustment for potential confounders. The inclusion of a diverse geographical population also enhances the generalizability of our findings to comparable higher-income countries.This study has several potential limitations. We did not measure intermediary outcomes that might offer explanatory pathways to explain lower mortality, nor did we measure the incidence of hyperkalemia. Data on potassium concentration of dialysis bath, urine output, and residual kidney function were not available. Fruit and vegetable intake was self-reported and comprised one single measurement, which may have led to recall bias, measurement bias, and misclassification of the exposure. The food frequency questionnaire has been validated for the general population against plasma phospholipid fatty acids (20), but not compared with other dietary assessment methods or within the hemodialysis setting. The exclusion of participants with missing or erroneous identification code, or incomplete or implausible food frequency questionnaire data, may have resulted in selection bias. Residual confounding from unmeasured variables (such as kidney residual function) associated with fruit and vegetable consumption cannot be excluded. Finally, incomplete adjudication of cause of death may have led to misattribution of cardiovascular deaths as noncardiovascular, although this should not have affected our conclusions.

In conclusion, the intake of fruit and vegetables in the hemodialysis population is far below the recommended levels in the general population. At this low level of intake, a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables may reduce all-cause and noncardiovascular mortality. A randomized trial evaluating potential benefits and harms of fruit and vegetable consumption could provide stronger evidence for effective dietary recommendations among patients on hemodialysis.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the provider of renal services, Diaverum, for covering overhead costs for study coordinators in each contributing country and material printing. We are grateful to the Global Asthma and Allergy Network of Excellence (GA2LEN) for facilitating the use of the GA2LEN food frequency questionnaire. Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article after deidentification will be available beginning 3 months and ending 5 years after article publication, to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. Proposals should be directed to Professor G.F.M. Strippoli at gfmstrippoli@gmail.com. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

The Dietary Intake, Death and Hospitalization in Adults with ESKD Treated with Hemodialysis (DIET-HD) study received unrestricted funding from Diaverum, a provider of renal services. Funding was applied to cover overhead costs for study coordinators in each contributing country and material printing.

The funding organization had no role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The DIET-HD investigators and dieticians (Diaverum) are as follows. Argentina: A. Badino, L. Petracci, C. Villareal, M. Soto, M. Arias, F. Vera, V. Quispe, S. Morales, D. Bueno, R. Bargna, G. Peñaloza, L. Alcalde, J. Dayer, A. Milán, N. Centurión, A. Ramos, E. De Orta, S. Menardi, N. Austa Bel, E. Marileo, N. Junqueras, C. Favalli, R. Trioni, G. Valle, M. López, C. Marinaro, A. Fernandez, J. Corral, E. Nattiello, S. Marone, J. García, G. Carrizo, P. González, O. Delicia, M. Maza, M. Chauque, J. Mora, D. Grbavac, L. López, M. Alonso, C. Villalba, M. Simon, M. Cernadas, C. Moscatelli, I. Vilamajó, C. Tursky, M. Martínez, F. Villalba, D. Pereira, S. Araujo, H. López, V. Alonso, B. Vázquez, M. Rapetti, S. Raña, M. Capdevila, C. Ljubich, M. Acosta, M. Coombes, V. Doria, M. Ávila, D. Cáceres, E. Geandet, C. Romero, E. Morales, C. Recalde, S. Marone, M. Casanú, B. Lococo, O. Da Cruz, C. Focsaner, D. Galarce, L. Albarracín, E. Vescovo, M. Gravielle, D. Florio, L. Baumgart, M. Corbalán, V. Aguilera, O. Hermida, C. Galli, L. Ziombra, A. Gutierrez, S. Frydelund, A. Hardaman, A. Maciel, M. Arrigo, C. Mato Mira, J. Leibovich, R. Paparone, E. Muller, A. Malimar, I. Leocadio, W. Cruz, S. Tirado, A. Peñalba, R. Cejas, S. Mansilla, C. Campos, E. Abrego, P. Chávez, G. Corpacci, A. Echavarría, C. Engler, P. Vergara, M. Hubeli, G. Redondo, B. Noroña; France: C. Boriceanu, M. Lankester, J.L. Poignet, Y. Saingra, M. Indreies, J. Santini, Mahi A., A. Robert, P. Bouvier, T. Merzouk, F. Villemain, A. Pajot, F. Tollis, M. Brahim-Bounab, A. Benmoussa, S. Albitar, M.C. Guimont, P. Ciobotaru, A. Guerin, M. Diaconita; Germany: S.H. Hoischen, J. Saupe, I. Ullmann S. Grosser, J. Kunow, S. Grueger, D. Bischoff, J. Benders, P. Worch, T. Pfab, N. Kamin, M. Roesch M. May; Hungary: K. Albert, I. Csaszar, E. Kiss, D. Kosa, A. Orosz, J. Redl, L. Kovacs, E. Varga, M. Szabo, K. Magyar, E. Zajko, A. Bereczki, J. Csikos, E. Kerekes, A. Mike, K. Steiner, E. Nemeth, K. Tolnai, A. Toth, J. Vinczene, Sz. Szummer, E. Tanyi, M. Szilvia; Italy: A.M. Murgo, N. Sanfilippo, N. Dambrosio, C. Saturno, G. Matera, M. Benevento, V. Greco, G. di Leo, S. Papagni, F. Alicino, A. Marangelli, F. Pedone, A.V. Cagnazzo, R. Antinoro, M.L. Sambati, C. Donatelli, F. Ranieri, F. Torsello, P. Steri, C. Riccardi, A. Flammini, L. Moscardelli, E. Boccia, M. Mantuano, R. Di Toro Mammarella, M. Meconizzi, R. Fichera, A. D’Angelo, G. Latassa, A. Molino, M. Fici, A. Lupo, G. Montalto, S. Messina, C. Capostagno, G. Randazzo, S. Pagano, G. Marino, D. Rallo, A. Maniscalco, O.M. Trovato, C. Strano, A. Failla, A. Bua, S. Campo, P. Nasisi, A. Salerno, S. Laudani, F. Grippaldi, D. Bertino, D.V. Di Benedetto, A. Puglisi, S. Chiarenza, M. Lentini Deuscit, C.M. Incardona, G. Scuto, C. Todaro, A. Dino, D. Novello, A. Coco; Poland: E. Bocheńska-Nowacka, A. Jaroszyński, J. Drabik, M. Wypych-Birecka, D. Daniewska, M. Drobisz, K. Doskocz, G. Wyrwicz-Zielińska, A. Kosicki, W. Ślizień, P. Rutkowski, S. Arentowicz, S. Dzimira, M. Grabowska, J. Ostrowski, A. Całka, T. Grzegorczyk, W. Dżugan, M. Mazur, M. Myślicki, M. Piechowska, D. Kozicka; Portugal: V. de Sá Martins, L. Aguiar, A.R. Mira, B. Velez, T. Pinheiro; Romania: E. Agapi, C.L. Ardelean, A. Baidog, G. Bako, M. Barb, A. Blaga, E. Bodurian, V. Bumbea, E. Dragan, D. Dumitrache, L. Florescu, N. Havasi, S. Hint, R. Ilies, A.G.M. Mandita, R.I. Marian, S.L. Medrihan, L. Mitea, S. Mitea, R. Mocanu, D.C. Moro, M. Nitu, M.L. Popa, M. Popa, E. Railean, A.R. Scuturdean, K. Szentendrey, C.L. Teodoru, A. Varga; Spain: M. García, M. Olaya, V. Abujder, J. Carreras, A. López, F. Ros, G. Cuesta, A. García, E. Orero, E. Ros, S. Bea, J.L. Pizarro, S. Luengo, A. Romero, M. Navarro, L. Cermeño, A. Rodriguez, D. Lopez, A. Barrera, F. Montoya, J. Tajahuerce, M. Carro, M.Q. Cunill, S. Narci, T. Ballester, M.J. Soler, S. Traver, P.P. Buta, L. Cucuiat, L. Rosu, I. Garcia, C.M. Gavra, R. Gonzalez, S. Filimon, M. Peñalver, V. Benages, M.I. Cardo, E. García, P. Soler, E. Fernnandez, F. Popescu, R. Munteanu, E. Tanase, F. Sagau, D. Prades, S. Esteller, E. Gonzalez, R. Martinez, A. Diago, J. Torres, E. Perez, C. Garcia, I. Lluch, J. Forcano, M. Fóns, A. Rodríguez, N.A. Millán, J. Fernández, B. Ferreiro, M. Otero, V. Pesqueira, S. Abal, R. Álvarez, C. Jorge, I. Rico, J. de Dios Ramiro, L. Duzy, A. Soto, J.L. Lopez, Y. Diaz, I. Herrero, M. Farré, C. Blasco, S. Ferrás, M.J. Agost, C. Miracle, J. Farto; Sweden: J. Goch, K.S. Katzarski, A. Wulcan. Turkey: H. Akbiber, H. Arslan, L. Bicen, A. Buyukkiraz, R. Celik, I.S. Dogan, S. Erkalkan, A. Ertas, U. Hark, E. Iravul, M. Karakaya, K. Mengu, S. Ongun, Z. Ozkan, A. Ozlu, N. Ozveren, H.M. Sifil, N. Sonmez Turksoz, Z. Yilmaz.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Does an Apple (or Many) Each Day, Keep Mortality Away?,” on pages 180–181.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.08580718/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Combined intake of fruits and vegetables by country.

Supplemental Table 2. Adjusted association (hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals) between baseline clinical characteristics and fruit and vegetable intake with mortality (clustered by country).

Supplemental Table 3. Adjusted mortality hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) by fruit and vegetable intake (tertiles of serving per week) and protein intake from fruit and vegetables (1 g/d increase).

Supplemental Table 4. All-cause mortality hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for fruit and vegetable intake.

Supplemental Table 5. Cardiovascular mortality hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for fruit and vegetable intake.

Supplemental Table 6. Noncardiovascular mortality hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for fruit and vegetable intake.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System (USRDS) : USRDS 2017 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Jager DJ, Grootendorst DC, Jager KJ, van Dijk PC, Tomas LM, Ansell D, Collart F, Finne P, Heaf JG, De Meester J, Wetzels JF, Rosendaal FR, Dekker FW: Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality among patients starting dialysis. JAMA 302: 1782–1789, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, Drüeke TB, Floege J, Goodman WG, Herzog CA, Kubo Y, London GM, Mahaffey KW, Mix TC, Moe SM, Trotman ML, Wheeler DC, Parfrey PS; EVOLVE Trial Investigators : Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 367: 2482–2494, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, Harris A, Johnson DW, Kesselhut J, Li JJ, Luxton G, Pilmore A, Tiller DJ, Harris DC, Pollock CA; IDEAL Study : A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 363: 609–619, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Cheung AK, Daugirdas JT, Greene T, Kusek JW, Allon M, Bailey J, Delmez JA, Depner TA, Dwyer JT, Levey AS, Levin NW, Milford E, Ornt DB, Rocco MV, Schulman G, Schwab SJ, Teehan BP, Toto R; Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study Group : Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 347: 2010–2019, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, Strippoli GF: Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 157: 263–275, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer SC, Di Micco L, Razavian M, Craig JC, Perkovic V, Pellegrini F, Copetti M, Graziano G, Tognoni G, Jardine M, Webster A, Nicolucci A, Zoungas S, Strippoli GF: Effects of antiplatelet therapy on mortality and cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes in persons with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 156: 445–459, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 916: i–viii, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FDR, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WMM, Binno S; ESC Scientific Document Group : 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 37: 2315–2381, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J; American Heart Association Nutrition Committee : Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 114: 82–96, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Ouyang Y, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhao G, Bao W, Hu FB: Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 349: g4490, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T, Greenwood DC, Riboli E, Vatten LJ, Tonstad S: Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 46: 1029–1056, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhan J, Liu YJ, Cai LB, Xu FR, Xie T, He QQ: Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57: 1650–1663, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazzano LA, Serdula MK, Liu S: Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 5: 492–499, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alissa EM, Ferns GA: Dietary fruits and vegetables and cardiovascular diseases risk. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57: 1950–1962, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JT, Palmer SC, Wai SN, Ruospo M, Carrero JJ, Campbell KL, Strippoli GF: Healthy dietary patterns and risk of mortality and ESRD in CKD: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 272–279, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National and Kidney Foundation (NKF) : Potassium and Your CKD Diet. Available at: https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/potassium. Accessed July 1, 2018

- 18.Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Campbell KL, Garcia Larsen V, Saglimbene V, Natale P, Gargano L, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Tonelli M, Knight J, Bednarek-Skublewska A, Celia E, Del Castillo D, Dulawa J, Ecder T, Fabricius E, Frazão JM, Gelfman R, Hoischen SH, Schön S, Stroumza P, Timofte D, Török M, Hegbrant J, Wollheim C, Frantzen L, Strippoli GF; DIET-HD Study investigators : Nutrition and dietary intake and their association with mortality and hospitalisation in adults with chronic kidney disease treated with haemodialysis: Protocol for DIET-HD, a prospective multinational cohort study. BMJ Open 5: e006897, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative : The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61: 344–349, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Larsen V, Luczynska M, Kowalski ML, Voutilainen H, Ahlström M, Haahtela T, Toskala E, Bockelbrink A, Lee HH, Vassilopoulou E, Papadopoulos NG, Ramalho R, Moreira A, Delgado L, Castel-Branco MG, Calder PC, Childs CE, Bakolis I, Hooper R, Burney PG; GA2LEN-WP 1.2 ‘Epidemiological and Clinical Studies’ : Use of a common food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) to assess dietary patterns and their relation to allergy and asthma in Europe: Pilot study of the GA2LEN FFQ. Eur J Clin Nutr 65: 750–756, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Food Standards Agency. Food Portion Sizes (Maff Handbook) 3rd Revised Edition. Mills A, Patel S, Crawley E. Stationery Office Books (TSO), UK, 2005. Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Food-Portion-Sizes-Maff-Handbook/dp/0112429610

- 22.Roe M, Pinchen H, Church S, Finglas P: The McCance and Widdowsons's The Composition of Foods Seventh Summary Edition and Updated Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset. Nutr Bull 40: 36–39, 2015. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid. Accessed July 1, 2018

- 23.Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, Reguant J, Trichopoulou A, Dernini S, Medina FX, Battino M, Belahsen R, Miranda G, Serra-Majem L; Mediterranean Diet Foundation Expert Group : Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr 14(12A): 2274–2284, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ESRD Death Notification Form (CMS 2746): ESRD Analytical Methods of the United States Renal Data System, Volume 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/CMS-Forms/CMS-Forms/downloads/cms2746.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2018

- 25.ESRD Analytical Methods of the United States Renal Data System, Volume 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_00_appx.aspx. Accessed July 1, 2018

- 26.Durrleman S, Simon R: Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 8: 551–561, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trichopoulou A, Orfanos P, Norat T, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Ocké MC, Peeters PH, van der Schouw YT, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Boffetta P, Nagel G, Masala G, Krogh V, Panico S, Tumino R, Vineis P, Bamia C, Naska A, Benetou V, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Pera G, Martinez-Garcia C, Navarro C, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Dorronsoro M, Spencer EA, Key TJ, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Kesse E, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berglund G, Wirfalt E, Hallmans G, Johansson I, Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K, Hundborg HH, Riboli E, Trichopoulos D: Modified Mediterranean diet and survival: EPIC-elderly prospective cohort study. BMJ 330: 991, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakasugi M, Kazama JJ, Yamamoto S, Kawamura K, Narita I: Cause-specific excess mortality among dialysis patients: Comparison with the general population in Japan. Ther Apher Dial 17: 298–304, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jager DJ, Vervloet MG, Dekker FW: Noncardiovascular mortality in CKD: An epidemiological perspective. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 208–214, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ash S, Campbell KL, Bogard J, Millichamp A: Nutrition prescription to achieve positive outcomes in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Nutrients 6: 416–451, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller V, Mente A, Dehghan M, Rangarajan S, Zhang X, Swaminathan S, Dagenais G, Gupta R, Mohan V, Lear S, Bangdiwala SI, Schutte AE, Wentzel-Viljoen E, Avezum A, Altuntas Y, Yusoff K, Ismail N, Peer N, Chifamba J, Diaz R, Rahman O, Mohammadifard N, Lana F, Zatonska K, Wielgosz A, Yusufali A, Iqbal R, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Khatib R, Rosengren A, Kutty VR, Li W, Liu J, Liu X, Yin L, Teo K, Anand S, Yusuf S; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators : Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 390: 2037–2049, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jadoul M, Karaboyas A, Goodkin DA, Tentori F, Li Y, Labriola L, Robinson BM: Potassium-binding resins: Associations with serum chemistries and interdialytic weight gain in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol 39: 252–259, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaaban A, Abouchacra S, Gebran N, Abayechi F, Hussain Q, Al Nuaimi N, Hassan ME: Potassium binders in hemodialysis patients: A friend or foe? Ren Fail 35: 185–188, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE: A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 371–381, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St-Jules DE, Goldfarb DS, Sevick MA: Nutrient non-equivalence: Does restricting high-potassium plant foods help to prevent hyperkalemia in hemodialysis patients? J Ren Nutr 26: 282–287, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong A, Crowe S, Chando S, Cass A, Chadban SJ, Chapman JR, Gallagher M, Hawley CM, Hill S, Howard K, Johnson DW, Kerr PG, McKenzie A, Parker D, Perkovic V, Polkinghorne KR, Pollock C, Strippoli GF, Tugwell P, Walker RG, Webster AC, Wong G, Craig JC: Research priorities in CKD: Report of a national workshop conducted in Australia. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 212–222, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.