Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, and its pathogenesis is initiated by the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) into extracellular plaques. Apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) is the largest genetic risk factor for sporadic AD and contributes to AD pathogenesis by influencing clearance and seeding of the initial aggregation of Aβ. In this issue of the JCI, Tachibana et al. investigated the relationship between neuronal LRP1 expression and ApoE4-mediated seeding of Aβ and showed that knockout of neuronal LRP1 prevents the increase in Aβ pathology caused by ApoE4 expression. These findings give insight into potential therapeutic targets for the preclinical phase of AD and the pathogenesis of Aβ pathology.

Amyloid-β pathology in Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the aggregation and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) and τ proteins, which are ultimately associated with dementia and neurodegeneration. Aβ pathology is characterized by the accumulation of Aβ into diffuse and neuritic plaques, as well as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which begins to accumulate 15 to 20 years before the onset of symptoms (1). This rise in Aβ pathology plateaus near the onset of symptoms and is followed by aggregation and spreading of τ from the medial temporal lobe to the neocortex, which is correlated with cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. As Aβ aggregation is likely to be the initiating event in the pathogenesis of AD (2), understanding the initiation and progression of Aβ pathology continues to be of interest for developing therapeutics.

Aβ pathology is driven by the initial seeding of Aβ into oligomeric and insoluble species, which accumulate in extracellular Aβ plaques. Seeding involves the process by which a misfolded protein is able to induce the misfolding of other molecules of the same protein. Aβ has been shown to have prion-like properties: individuals treated with cadaver-derived growth hormone containing Aβ seeds have accelerated Aβ pathology (3), and injection of Aβ fibrils into a mouse model of Aβ amyloidosis accelerates Aβ pathology (4). In sporadic cases, seeding of Aβ has been hypothesized to be due to a variety of causes, including accumulation of Aβ in early endosomes, slowed or altered soluble Aβ clearance, and somatic gene replication, resulting in overexpression of Aβ (5–7). Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), specifically the ApoE4 allele, contributes to the seeding process in vivo (8, 9). Human ApoE has three major isoforms: ApoE2 (Cys112, Cys158), ApoE3 (Cys112, Arg158), and ApoE4 (Arg112, Arg158). ApoE4 is the largest risk factor for AD; one copy of the allele increases AD risk about 4-fold and two copies about 15-fold (10).

Through complementary methods, it was shown that ApoE4 affects the early seeding of Aβ pathology. In one study, lowering ApoE levels with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) resulted in a reduction of Aβ pathology only when used prior to the onset of Aβ aggregation (8). Treating mice with ASOs at later time points had no effect on Aβ pathology. Another study used a cell-specific and inducible tet-off Cre system (9) to turn on ApoE4 expression prior to plaque deposition, leading to a significant increase in Aβ pathology. However, turning on ApoE4 expression later had no significant effect. Together, these studies demonstrate that ApoE4 exerts its deleterious effects by promoting the seeding of Aβ.

Another important factor that contributes to Aβ pathology is the rate of Aβ clearance from the extracellular space. This clearance occurs by (a) enzymes such as neprilysin; (b) cellular internalization via receptors such as LDL receptor (LDLR), LDLR-related protein 1 (LRP1), and heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and being degraded by glial or neuronal cells; (c) being trancytosed by endothelial cells across the blood-brain barrier, and (d) being transported by interstitial fluid (ISF)/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow into the meningeal lymphatic system. ApoE can compete with Aβ for binding to receptors and affect the clearance of Aβ from the extracellular space (11). ApoE can also affect the trafficking and degradation of Aβ through the endolysosomal pathway (12).

ApoE4-mediated seeding of Aβ is dependent on neuronal LRP1

In this issue of the JCI, Tachibana et al. provide evidence that neuronal LRP1 is an essential player in mediating ApoE4’s effect on Aβ and thus AD risk (13). The authors first investigated the relationship between LRP1 expression and insoluble Aβ levels in human postmortem samples from the temporal cortex. In individuals with an ApoE3/ApoE3 genotype, there was a negative correlation between insoluble Aβ levels and LRP1 expression. In contrast, in ApoE3/ApoE4 and ApoE4/ApoE4 individuals, there was a positive correlation between insoluble Aβ levels and LRP1 expression. These contrasting findings can be best understood as a result of LRP1 contributing more to the clearance of Aβ in the context of the ApoE3/ApoE3 genotype and seeding in the presence of ApoE4.

To further explore this finding, the authors utilized mice that had human ApoE3 or ApoE4 knocked in to the endogenous murine ApoE locus. These mice were crossed with APP/PS1 mice, which express familial AD mutations that lead to Aβ deposition, thus acting as a model of Aβ amyloidosis. In these mice, the authors confirmed the known effect of ApoE4 expression, where mice expressing the ApoE4 allele have a more severe Aβ pathology compared with mice expressing ApoE3 (8, 9). In order to assess the impact of neuronal LRP1 expression on Aβ pathology in the context of ApoE3 and ApoE4, APP/PS1; ApoE3 and APP/PS1; ApoE4 mice were crossed to neuronal LRP1 knockout (nLrp1–/–) mice. In both the cortex and hippocampus, the authors found that nLRP1–/–, in the presence of ApoE4, decreased Aβ plaque burden to the levels seen in APP/PS1; ApoE3 and APP/PS1; ApoE3; nLrp1–/– mice. This is a significant finding, as it suggests that the early seeding of Aβ as a result of ApoE4 expression depends on neuronal LRP1.

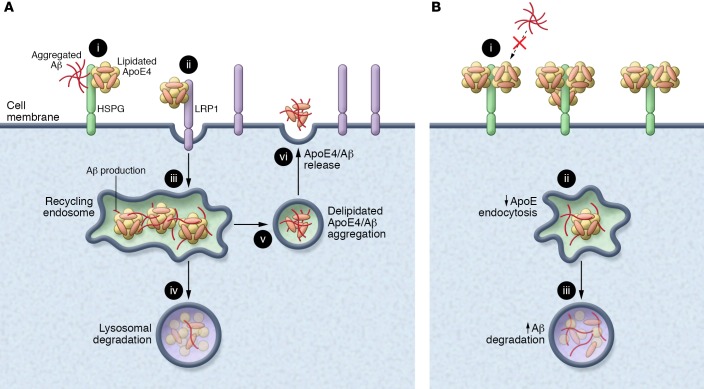

The mechanism of how ApoE4 contributes to the seeding of Aβ is still not fully understood, but this study provides some intriguing results that help to potentially illuminate this mechanism (see Figure 1). LRP1 is a major neuronal ApoE receptor and is responsible for the majority of ApoE flux through neurons (14). ApoE binds LRP1, is endocytosed, and is degraded or recycled through the endolysosomal pathway. Since the addition of ApoE to neuronal cell cultures increases the rate of Aβ degradation, ApoE has been implicated in the degradation of Aβ by acting as a chaperone for Aβ through the endolysosomal pathway (12). It is known that ApoE4 leads to disruption of the endolysosomal pathway (15), which may lead to the accumulation of Aβ within early endosomes where the Aβ is produced by the cleavage of endocytosed APP by β- and γ-secretase (5, 16). The accumulation of Aβ, and potentially its interaction with nonlipidated ApoE4, could promote its aggregation. These aggregates could then be released into the extracellular space through recycling endosomes. This would initiate the seeding process and contribute to the aberrant aggregation of Aβ in early Aβ pathogenesis.

Figure 1. ApoE4 seeding of Aβ.

(A) ApoE4 seeds Aβ aggregation in the presence of LRP1. (i) ApoE4 and Aβ compete for binding to HSPGs. (ii) LRP1 binds lipidated ApoE4, which is then endocytosed. (iii) Recycling endosomes are sites of Aβ production. ApoE4 may interact with Aβ to seed its aggregation. (iv) Aβ and lipidated ApoE4 are degraded in lysosomes. (v) Delipidated ApoE4 seeds the aggregation of Aβ. (vi) Aggregated ApoE4 and Aβ are released into the extracellular space. (B) Neuronal LRP1 knockout prevents ApoE4 seeding of Aβ. In the absence of LRP1 (i), ApoE4 associates with HSPGs and blocks binding of Aβ. (ii) Less ApoE4 is endocytosed (iii). ApoE4 contributes less to Aβ seeding, and more Aβ is degraded through the lysosomal pathway.

An alternate, perhaps complementary, explanation is suggested by the authors. The authors show that nLrp1–/– leads to a greater proportion of ApoE4 in the detergent-soluble fraction. This could suggest greater association of ApoE4 with the cell surface, particularly HSPGs. It has been previously shown that HSPGs play an important role in ApoE-mediated degradation of Aβ, as adding heparin to neuronal cultures prevents the increase in Aβ degradation seen by adding ApoE to the cultures (12). However, further research is needed to define the mechanism by which ApoE4 interacts with neuronal LRP1 to induce Aβ seeding.

Therapeutic strategies for Aβ and ApoE genotype

The therapeutic implications of this study point to neuronal LRP1 as a potential therapeutic target. Lowering ApoE levels or blocking neuronal LRP1 in early stages of Aβ pathogenesis could be a measure for reducing Aβ seeding and allowing for clearance of Aβ from the extracellular space. However, this treatment may be beneficial primarily in ApoE4 carriers in which Aβ seeding is exacerbated by ApoE4. In the case of ApoE3 homozygotes, the treatment may be ineffective, or even deleterious, as it would interfere with neuronal clearance of Aβ through the LRP1 receptor (14). For these individuals, boosting neuronal LRP1 expression may actually be beneficial, as it would increase the degradation of Aβ.

This also highlights the importance of biomarkers in order to identify preclinical AD patients for whom this intervention would be most successful. As clinical signs typically arise after Aβ pathology has plateaued, the impact of treatment targeting ApoE or LRP1 might be limited in affecting further Aβ accumulation. Rather, at this stage, treatments might need to target τ pathology or the innate immune response in order to slow disease progression. Advances in personalized medicine will also be important, as the treatment for AD will likely need to be tailored to the ApoE genotype of the individual. Treatments targeting ApoE and LRP1 to influence Aβ-related pathogenesis would seem to be most appropriate in the preclinical stage of AD.

Conclusion

This study provides greater mechanistic insight into how ApoE4 contributes to Aβ pathogenesis. The results strongly suggest that ApoE4 promotes the seeding of Aβ in early stages of the disease through specific interaction with neuronal LRP1. This finding suggests avenues for further research and therapeutic strategies. Further studies focusing on understanding how ApoE4 modulates LRP1 activity and the contributions of the endolysosomal pathway on Aβ seeding may be fruitful. It also suggests the potential for LRP1 as a therapeutic target in intervening in preclinical AD and halting the progression of Aβ pathology before the onset of preclinical symptoms. Research into these mechanisms will help advance the goal of finding an effective therapeutic for AD by 2025.

Version 1. 02/11/2019

Electronic publication

Version 2. 03/01/2019

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: DMH is a cofounder and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. He is on the scientific advisory board of Genentech, Denali Therapeutics, and Proclara Biosciences. His lab receives research grants from C2N Diagnostics and AbbVie.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2019;129(3):969–971. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI127578.

See the related article at APOE4-mediated amyloid-β pathology depends on its neuronal receptor LRP1.

References

- 1.Bateman RJ, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(9):698–712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purro SA, et al. Transmission of amyloid-β protein pathology from cadaveric pituitary growth hormone. Nature. 2018;564(7736):415–419. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer F, Eisele YS, Fritschi SK, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Soluble Aβ seeds are potent inducers of cerebral β-amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2011;31(41):14488–14495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3088-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cataldo AM, et al. Aβ localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Aβ elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(10):1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mawuenyega KG, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330(6012):1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MH, et al. Somatic APP gene recombination in Alzheimer’s disease and normal neurons. Nature. 2018;563(7733):639–645. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huynh TV, et al. Age-Dependent effects of apoE reduction using antisense oligonucleotides in a model of β-amyloidosis. Neuron. 2017;96(5):1013–1023.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu CC, et al. ApoE4 accelerates early seeding of amyloid pathology. Neuron. 2017;96(5):1024–1032.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deming Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies four novel loci associated with Alzheimer’s endophenotypes and disease modifiers. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133(5):839–856. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1685-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verghese PB, et al. ApoE influences amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance despite minimal apoE/Aβ association in physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(19):E1807–E1816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, et al. Differential regulation of amyloid-β endocytic trafficking and lysosomal degradation by apolipoprotein E isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(53):44593–44601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.420224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tachibana M, et al. APOE4-mediated amyloid-β pathology depends on its neuronal receptor LRP1. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(3):1272–1277. doi: 10.1172/JCI124853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanekiyo T, et al. Neuronal clearance of amyloid-β by endocytic receptor LRP1. J Neurosci. 2013;33(49):19276–19283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3487-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuriel T, et al. The endosomal-lysosomal pathway is dysregulated by APOE4 expression in vivo. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:702. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das U, et al. Visualizing APP and BACE-1 approximation in neurons yields insight into the amyloidogenic pathway. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(1):55–64. doi: 10.1038/nn.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]