Abstract

Molecular genetic research provides unprecedented opportunities to examine genotypephenotype correlations underlying complex syndromes. To investigate pathogenic mutations and genotype-phenotype relationships in diverse neurodegenerative conditions, we performed a rare variant analysis of damaging mutations in autopsy-confirmed neurodegenerative cases from the Johns Hopkins Brain Resource Center (n=1,243 patients). We used NeuroChip genotyping and C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat analysis to rapidly screen our cohort for disease-causing mutations. In total, we identified 42 individuals who carried a pathogenic mutation in LRRK2, GBA, APP, PSEN1, MAPT, GRN, C9orf72, SETX, SPAST, or CSF1R, and we provide a comprehensive description of the diverse clinicopathological features of these well-characterized cases. Our study highlights the utility of high-throughput genetic screening arrays to establish a molecular diagnosis in individuals with complex neurodegenerative syndromes, to broaden disease phenotypes and to provide insights into unexpected disease associations.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, NeuroChip, genotype-phenotype, brain bank

1. Introduction

Age-related neurodegenerative diseases are a growing public health concern due to population aging within developed societies. For example, the U.S. population over 65 years of age will nearly double by 2050 and the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease is projected to dramatically increase (Hebert et al., 2013; Ortman et al., 2014). There is a critical need to develop disease-modifying treatments to ameliorate these age-related diseases. Improved understanding of the pathogenic molecular defects that lead to neurodegeneration is crucial for achieving this goal.

Until recently, systematic screening of disease-causing mutations was prohibitively expensive and cumbersome. This has hampered the use of genetic testing in the clinic, where the standard approach is to screen only a small number of mutations in patients with a clear family history and distinct phenotypes. Recent advances in high-throughput genotyping technologies are changing this approach, as they allow us to rapidly screen thousands of disease-associated genetic variants at low cost for diverse clinical and scientific applications. It is now feasible to broadly apply this type of genetic screening to large patient populations to study the diverse genotype-phenotype correlations and to identify unexpected disease associations.

To illustrate this point, we genotyped 1,243 pathologically confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases using the NeuroChip, an inexpensive, off-the-shelf genotyping array that rapidly detects mutations and genetic risk variants previously implicated in neurological disease (Blauwendraat et al., 2017). We chose this autopsy-based patient series as it provides diagnostic certainty and avoids the confusion that may arise from mimic syndromes in clinically heterogeneous neurodegenerative conditions.

Analyzing these high-yield data for disease-causing mutations, we identified a diverse spectrum of mutation carriers in this well-characterized cohort and observed novel genotype-phenotype correlations. For example, we provide compelling evidence that the pathogenic LRRK2 G2019S mutation not only causes Parkinson’s disease, but may also present with pathological changes consistent with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). Our data established a molecular diagnosis in several patients where the clinical and pathological diagnosis gave disparate results and led to the identification of a molecular cause in cases with unclassified neurodegenerative conditions. Importantly, we have created a resource of genomic findings in pathologically-defined neurodegenerative diseases. We expect the number of genes related to neurodegeneration to grow over time, and other researchers can freely access our pathologically and genetically characterized cohort to replicate and extend their findings.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

Tissue samples were obtained from the Johns Hopkins Brain Resource Center, which encompasses the Johns Hopkins Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research, the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, and autopsy cases from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging. Patients included in this cohort were referred by clinical and research centers at Johns Hopkins University and across academic centers in Maryland, USA. All participants gave written, informed consent for post-mortem brain donation. A total of 1,243 neurodegenerative disease cases were selected for genotyping (Table 1 shows a detailed summary of the study cohort) using the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: 1) each case had a pathological diagnosis of a neurodegenerative syndrome, 2) had no history of a primary or secondary CNS malignancy and 3) no known genetic cause of disease.

Table 1.

Johns Hopkins brain bank cohort description

| Disease Category | Sample Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological Diagnosis | No. of Cases | Age at Death (mean, ± SD) |

Sex (% Female) |

Race (% White) |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | 624 | 82 (±11) | 62% | 96% |

| Complex (more than one disease) | ||||

| AD + Lewy body disease (PD, LBD) | 216 | 79 (± 09) | 41% | 98% |

| AD + ALS-FTD | 27 | 80 (± 10) | 56% | 100% |

| AD + Atypical parkinsonism | 26 | 78 (±11) | 38% | 96% |

| Other complex cases | 40 | 79 (± 13) | 45% | 98% |

| Lewy body disease | ||||

| PD | 50 | 77 (± 10) | 32% | 98% |

| LBD | 49 | 78 (± 07) | 24% | 96% |

| ALS-FTD | 84 | 65 (± 13) | 45% | 100% |

| Atypical parkinsonism | ||||

| MSA | 13 | 67 (± 12) | 58% | 100% |

| PSP | 37 | 75 (± 07) | 42% | 95% |

| CBD | 7 | 73 (± 08) | 57% | 100% |

| Other neurodegenerative disease | ||||

| Rare neuro degenerative syndromes | 9 | 68 (± 14) | 33% | 100% |

| Unclassified neuro degenerative cases | 47 | 78 (±23) | 49% | 98% |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 14 | 79 (±11) | 50% | 100% |

| TOTAL | 1,243 | 79 (± 12) | 52% | 97% |

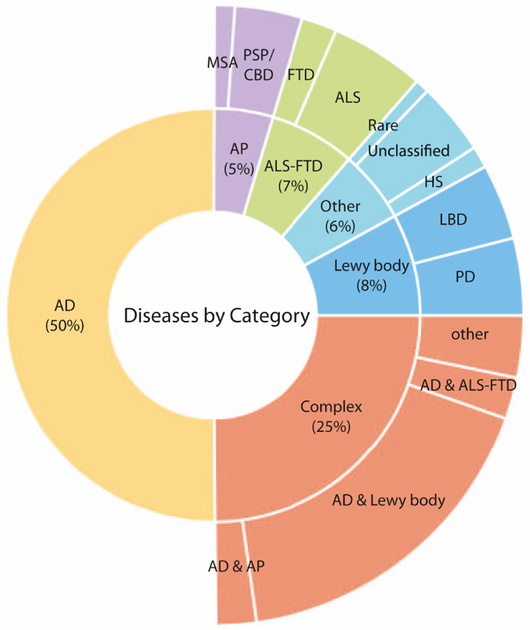

The cohort included the following neurodegenerative disease entities: Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), hippocampal sclerosis, Lewy body dementia (LBD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), as well as unclassified or rare neurodegenerative diseases. Individuals with more than one neurodegenerative disease, e.g. Alzheimer’s disease plus LBD, were labeled as ‘complex’ cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This multi-layer pie chart illustrates the composition of the Johns Hopkins brain bank cohort by disease category. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s dementia; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; AP, atypical parkinsonism; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; HS, hippocampal sclerosis; LBD, Lewy body dementia; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PD, Parkinson’s disease, PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy.

2.2. Genotyping

DNA was extracted from frozen brain tissue using phenol-chloroform extraction and diluted in TE buffer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Genotyping was performed using the NeuroChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), a microarray that is comprised of a tagging variant backbone (n=306,670 variants) and 179,467 variants of custom “neuro” content. This chip is designed for rapid, comprehensive, and affordable screening of known single nucleotide variants implicated in diverse neurodegenerative diseases. Variants included on this platform were reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD Professional 2016.4, QIAGEN), the NHGRI GWAS Catalog (www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/), the Parkinson Disease Mutation Database (www.molgen.vibua.be/PDMutDB), the Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Database (www.molgen.ua.ac.be/admutations/), the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/), literature review as well as ongoing research studies in neurodegenerative diseases. The detailed content of this versatile genotyping array has been described elsewhere (Blauwendraat et al., 2017). NeuroChip genotyping was carried out as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina). Briefly, for each sample a total of 250 ng of high-quality genomic DNA was amplified and enzymatically fragmented. The resulting fragments were alcohol-precipitated and resuspended in buffer. Next, the fragmented DNA solution was hybridized to the NeuroChip array using a Tecan Freedom EVO liquid-handling robot (Tecan, Research Triangle Park, NC). After hybridization, automated allele-specific, enzymatic base extension and fluorophore staining were performed. The stained genotyping arrays were washed, sealed and vacuum-dried prior to scanning them on the Illumina High-Scan system. Raw data files were imported into GenomeStudio (version 2.0, Genotyping Module, Illumina) using a custom-generated sample sheet, and genotypes were called using a GenCall threshold of 0.15. The resulting genotype data were exported in a ped-file format using the Illumina-to-PLINK module (version 2.1.4).

2.3. Quality control

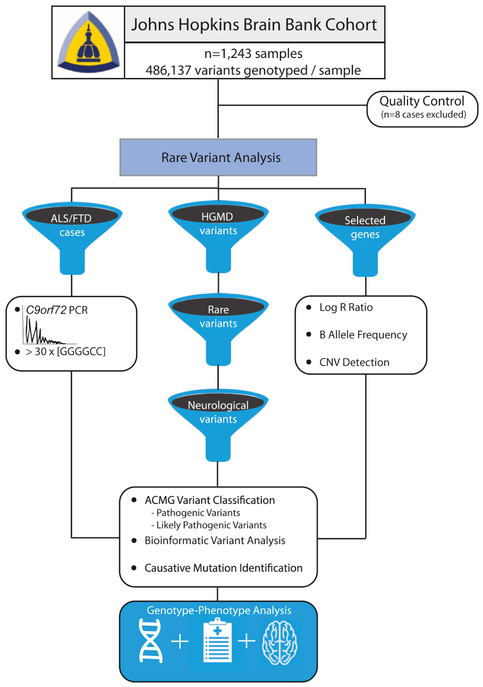

Quality control was conducted in PLINK (version 1.9) (Chang et al., 2015). Of the 1,243 genotyped samples, three were excluded due to a low call rate of <98%, four individuals were removed due to ambiguous gender, and one Alzheimer’s disease case due to Down syndrome was genotyped in error and excluded from the analysis. In total, 1,235 samples passed sample quality control and were evaluated for pathogenic mutations. An illustration showing the analysis workflow is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

This illustration shows an overview of the analysis workflow that we applied to identify patients with pathogenic mutations, including filtering the data to extract rare, damaging neurological mutations in the Human Genome Mutation Database content, performing C9orf72 repeat expansion screening in pathologically-confirmed ALS/FTD patients, and a copy number variant analysis of selected genes.

2.4. Rare variant analysis and variant validation

Monogenic diseases due to highly penetrant rare mutations are especially informative for genotype-phenotype correlations as they can be attributed to well-defined molecular defects. To identify such damaging mutations in our brain bank cohort, we conducted a rare variant analysis by filtering our data by the professionally curated Human Gene Mutation Database content (HGMD Professional 2016.4) included on the NeuroChip (n=8,086 disease-associated variants) (Blauwendraat et al., 2017). Taking into account that disease-causing mutations are rare due to selective pressure, we next excluded variants with a minor allele frequency > 0.005 using population frequency estimates from ANNOVAR (Wang et al., 2010) and variants with a maximum population frequency exceeding 50 alleles according to ExAC (version 0.3.1), (Lek et al., 2016), reducing the dataset to 446 variants. To rule out possible genotyping errors of the identified rare HGMD variants, we reviewed GenTrain scores and visualized Cartesian plots of genotype clusters in GenomeStudio (version 2.0, Genotyping Module, Illumina). Genotypes with borderline GenTrain scores (< 0.7), variants with ambiguous genotype cluster separation and multi-allelic variants were selected for validation using bi-directional Sanger sequencing using Big-Dye Terminator v.3.1 sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). Sequence reactions were run on an ABI 3730xl genetic analyzer and interpreted using Geneious software (version 10.0.7, Biomatters Ltd, Newark, NJ, USA). This validation step identified 10 variants that were not confirmed and excluded from the study. Next, we obtained pathogenicity prediction annotations (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, M-CAP, CADD) and nucleotide conservation predictions (GERP++) from ANNOVAR for all remaining rare HGMD variants (Adzhubei et al., 2010; Davydov et al., 2010; Jagadeesh et al., 2016; Kircher et al., 2014; Ng and Henikoff, 2003; Wang et al., 2010). We then reviewed all these variants for known association with neurological disease (n=328 variants). After exclusion of variants that were associated with non-neurological human traits/diseases, we determined variants according to ACMG consensus guidelines and focused on pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants that are presumed to be disease-causing (Richards et al., 2015). This step identified 21 missense mutations in one or more patients located within the genes LRRK2, GBA, APP, PSEN1, MAPT, GRN, SETX, SPAST, and CSF1R (Supplementary Table 1). Due to the fact that GBA has a pseudogene with high homology to the functional gene that may lead to false positive genotype calls, we performed validation experiments of all GBA variants using a Sanger sequencing method described elsewhere (Stone et al., 2000). This step identified one GBA variant (R159W) that was not confirmed and therefore excluded.

2.5. C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion screening

C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion is the most common, monogenic cause of ALS/FTD. Although the NeuroChip readily detects the previously described Finnish risk haplotype surrounding the C9orf72 locus (Laaksovirta et al., 2010), this haplotype is also commonly present in the control population and does not serve as a reliable proxy marker for identifying repeat expansion carriers. We therefore screened all ALS/FTD cases (n=84) for pathogenic hexanucleotide repeat expansions using repeat-primed PCR as described elsewhere (Renton et al., 2011). The resulting PCR amplicons were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). Expansions of > 30 GGGGCC repeats were interpreted as pathogenic.

2.6. Copy number variant analysis

Multiplications of SNCA, and homozygous or compound heterozygous copy number variation in PARK2 can rarely cause familial Parkinson’s disease (Fuchs et al., 2007; Kitada et al., 1998; Lucking et al., 1998; Singleton et al., 2003). Likewise, APP duplication or PSEN1 exon 9 deletion have been demonstrated as rare Mendelian causes of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Rovelet-Lecrux et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2001). Hence, we undertook a copy number variant analysis of these four genes using standard protocols described elsewhere (Matarin et al., 2008). Briefly, B-allele frequency and LogR ratio plots were constructed from GenomeStudio for each of the four gene loci ± 500,000 bp flanking regions and visually inspected for gene multiplications or deletions. Pathogenic copy number variants identified in this analysis were confirmed by quantitative PCR.

2.7. Genotype-phenotype analysis

Medical charts, pathology reports and histopathology sections of causative mutation carriers were reviewed and summarized by neuropathologists JCT and OP and board-certified neurologist SWS.

3. Results

3.1. Rare variant analysis

We performed genome-wide genotyping of 1,243 samples diagnosed with neurodegenerative diseases obtained from the Johns Hopkins Brain Bank using the NeuroChip array. This platform provided information for 468,137 variants/case, of which 8,086 variants are reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database, a collection of disease-associated genetic variants.

Using these samples, we identified a total of 42 patients (approximately 3.4% of the total cohort) carrying a damaging mutation in one or more of the following genes: 1) LRRK2, 2) GBA, 3) APP, 4) PSEN1, 5) MAPT, 6) GRN, 7) C9orf72, 8) SETX, 9) SPAST and 10) CSF1R. Clinical and pathological features of these individuals are shown in Table 2 and more detailed case-by-case descriptions are provided in the Supplementary Materials. We summarize the genetic characteristics, bioinformatic modeling data, and the pathogenicity predictions of the identified mutations in Supplementary Table 1. Below, we describe each of the mutation carriers categorized by gene, highlighting novel observations that arise from our data.

Table 2.

Genetic, clinical and pathological characteristics of patients with pathogenic mutations

| Patient ID | Genetic Characteristics | Clinical Characteristics | Pathological Features | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene(s) | Mutation(s) | Genotype/ ritance |

Clinical Diagnosis |

AAO (decade of life) |

AAD (decade of life) |

Sex | Race | FH | Path. Diagnosis |

Comment | |

| JHND964 | LRRK2 | p.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | FDD | fifth | eighth | M | B | + | AD, nigral neuronal loss | Intermediate level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies, tau threads |

| JHND875§ | LRRK2 | p.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | FDD | seventh | ninth | F | W | + | AD,LBD | Intermediate level AD pathology, LBD (neocortical subtype) |

| JHND739§ | LRRK2 | p.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | PD | eighth. | ninth | F | W | + | AD,PSP | High level AD pathology, PSP, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND1206 | LRRK2 | p.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | Parkins onism | fourth | ninth | F | W | NA | AD, nigral neuronal loss | Intermediate level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| GBA | p.N409S | hom(aut.rec) | |||||||||

| JHND717 | LRRK2 | p.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | FDD | fifth | eighth | M | W | + | AD, FTLD-Tau | intermediate level AD pathology, MLJJ-tau {eae subtype) |

| JHND823 | LRRK2 | P.G2019S | het(aut.dom.) | PD | seventh | eighth | M | W | NA | AD,PD | Low level AD pathology, PD (lmbic type) |

| JHND800 | GBA | p.D448H | het(aut.dom.) | PDD | fifth | seventh | M | W | − | AD,LBD | Low level AD pathology, LBD (neocortical type) |

| JHND1076 | GBA | p.D448H | het(aut.dom.) | PDD | seventh | ninth | F | W | + | PD | LBD (kmbic type), neurofibrillary tangles |

| JHND832 | GBA | p.T362I | het(aut.dom.) | DLB | fifth | seventh | F | W | + | AD,LBD | Low level AD pathology, LBD (neocortical type) |

| JHND805 | GBA | P.R87Q | het(aut.dom.) | PD/AD | sixth | seventh | M | W | + | AD,LBD | Intermediate level AD pathology, LBD (neocortical type) |

| JHND924 | APP | p.V717F | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fifth | eighth | F | W | + | AD,LBD | High level AD pathology, LBD (neocortical type) |

| JHND507† | APP | p.V717F | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fifth | sixth | M | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND360† | APP | p.V717F | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fifth | sixth | F | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND365‡ | APP | p.V717L | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fifth | sixth | F | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND204‡ | APP | p.V717L | het(aut.dom.) | AD | seventh | eighth | F | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND1189* | APP | Duplication | het(aut.dom.) | Dementia | third | sixth | M | W | + | AD,LBD,LD | High level AD pathology, LBD (brainstem type), CAA |

| JHND164* | APP | Duplication | het(aut.dom.) | Dementia | sixth | sixth | M | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, CAA |

| JHND265* | APP | Duplication | het(aut.dom.) | Dementia | sixth | seventh | M | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies, CAA |

| JHND542 | PSEN1 | p.T116I | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fourth | fifth | M | W | (+) | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND170 | PSEN1 | pM139I | het(aut.dom.) | Dementia | fourth | fifth | M | W | − | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND132 | PSEN1 | p.I143T | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fourth | fifth | F | W | − | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND594 | PSEN1 | p.R269H | het(aut.dom.) | AD | seventh | eighth | M | W | − | AD | High level AD pathology, no Lewy bodies |

| JHND623 | PSEN1 | P.A285V | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fifth | sixth | M | W | + | AD | High level AD pathology, sparse Lewy bodies |

| JHND1007 | MAPI | p.P301L | het(aut.dom.) | FTD | sixth | sixth | M | W | + | FTLD-Tau | Extensive phosphorylated tau deposition |

| JHND92 | MAPI | p.R5L | het(aut.dom.) | AD | NA | NA | M | W | NA | AD | Low level AD pathology |

| JHND700 | GRN | p.RHOX | het(aut.dom.) | AD | seventh | ninth | F | W | NA | FTLD-TDP | Ubiquitin and TDP-43 positive inclusions |

| JHND650 | C9orJ72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | seventh | seventh | M | B | + | ALS | Bunina bodies in anterior horn cells and pyramidal cells of Betz |

| JHND653 | C9orf72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | fifth | fifth | M | W | + | ALS | |

| JHND662 | C9orf72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | sixth | sixth | M | W | NA | ALS | |

| JHND669 | C9orp2 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | sixth | sixth | F | W | NA | ALS | |

| JHND628 | C9orf72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | AD | sixth | seventh | M | W | NA | FTLD | Ubiquitin positive inclusions |

| JHND676 | C9orf72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | fifth | sixth | F | W | + | ALS | Ubiquitin positive inclusions |

| JHND644 | C9orJ72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | fifth | fifth | M | W | + | ALS | |

| JHND625 | C9orp2 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | AD | seventh | ninth | F | W | − | FTLD | Ubiquitin positive inclusions, sparse neurofibrillary tangles |

| JHND1018 | C9orf72 | Repeat exp. | het(aut.dom.) | FTD | seventh | eighth | F | W | NA | FTLD | Ubiquitin and TPD-43 positive inclusions |

| JHND679 | SETX | p.L389S | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | second | eighth | F | W | + | ALS | Antenorhom cell loss |

| JHND1207 | SETX | p.L389S | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | first | ninth | F | W | + | ALS | Antenorhom cell loss, ubiquitin-positive axonal swelling |

| JHND665 | SETX | P.L389S | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | first | seventh | M | W | + | ALS | Antenorhom cell loss |

| JHND1196 | SPAST | p.R581X | het(aut.dom.) | HSP | fourth | ninth | F | W | (+) | Neurodegeneration | Frontopanetal atrophy, marked neurodegeneration |

| JHND1190 | CSF1R | p.M766T | het(aut.dom.) | AD | fourth | fifth | F | W | NA | Neuroaxonal dystrophy | Neuroaxonal dystrophy |

| JHND1195 | CSF1R | p.G589E | het(aut.dom.) | FTD | sixth | seventh | M | W | + | LD | Axonal spheroids and pigmented macrophages |

| JHND671 | CSF1R | p.L868P | het(aut.dom.) | ALS | sixth | sixth | M | W | NA | ALS | Marked loss of motor neurons with reactive astrocytosis |

Abbreviations (in alphabetical order): AAO, age at onset; AAD, age at death; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; aut.dom., autosomal dominant; aut.rec., autosomal recessive; B, Black; exp., expansion; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; FTLD, 3 frontotemporal lobar degeneration; HSP, hereditary spastic paraplegia; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; LBD, Lewy body dementia; LD, leukodystrophy; NA, data not available; NDD, neurodegenerative disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; W, White

JHND507 and JHND360 are first degree relatives;

JHND365 and JHND204 are first-degree relatives;

JHND875 and JHND739 are third-degree relatives;

JHND1189, JHND164 and JHND265 are first-degree relatives. Of note, age at onset and age at death are given as decades of life to protect privacy

3.1.1. LRRK2 mutations

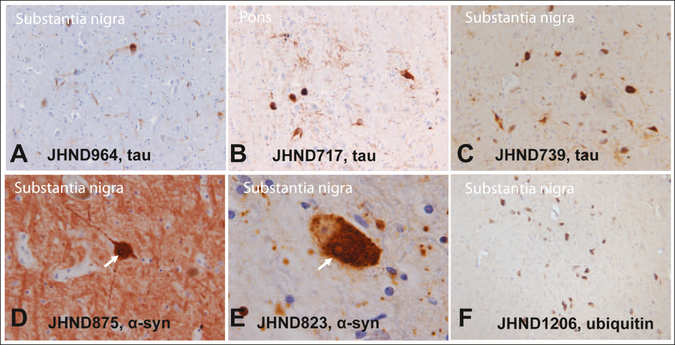

We identified six patients who were diagnosed with parkinsonism prior to their deaths, and who carried a pathogenic LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation. The clinicopathological characteristics of these six individuals were heterogeneous (Table 2). While all LRRK2 patients presented with parkinsonism, only three progressed toward dementia (JHND964, JHND875, and JHND717). On histopathology, only two of the six LRRK2 patients had typical, α-synuclein-positive Lewy body pathology consistent with a pathological diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (JHND823) or neocortical type LBD (JHND875; Figure 3, panels D and E). One patient (JHND1206) showed nigral neuronal loss without any tau or α-synuclein-positive inclusions (Figure 3, panel F). The genetic profile of this particular patient was complex as she was also homozygous for the pathogenic p.N409S GBA mutation known to cause Gaucher disease. The three remaining cases showed neuropathological findings typical for PSP in the form of tau-positive neurons, neuropil threads, tufted astrocytes, and coil bodies without any accompanying Lewy body pathology (Figure 3, panels A-C). Only two of these three patients fulfilled neuropathological criteria for a diagnosis of PSP, while the third case was interpreted as a forme fruste of PSP (JHND964). This observation provides strong support for the hypothesis that the LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation can occasionally cause PSP, as previously suggested by rare incidental cases (Rajput et al., 2006; Ruffmann et al., 2012; Sanchez-Contreras et al., 2017).

Figure 3.

This figure shows the histopathological heterogeneity associated with LRRK2-related parkinsonism in six patients with a pathogenic p.G2019S LRRK2 mutation. Three out of six cases had tau-positive neurons, neuropil threads, tufted astrocytes, and coil bodies consistent with a diagnosis of PSP (panels A, B, C: 20x magnification), but no Lewy body pathology. Two patients were found to have nigral neuronal loss with associated Lewy body pathology (panels D, E; Lewy bodies indicated by arrow). One patient had nigral neuronal loss without tau- or asynuclein-positive inclusion (panel F shows a few naturally pigmented nigral neurons; of note this patient was also homozygous for the pathogenic p.N409S GBA mutation). Magnification is 40x for D, 100x for E, and 10x for panel F.

For three of the six LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation carriers (JHND875, JHND823, and JHND739), we had sufficient brain tissue available to perform a solubility analysis of α-synuclein (Supplementary Materials). Western blotting found modest amounts of urea-soluble α-synuclein only in two of our LRRK2 p.G2019S cases that had Lewy body pathology on histopathological examination, whereas the third case, which was found to have tau-positive inclusions consistent with PSP on histopathological examination, had no α-synuclein deposition (JHND739) (Supplementary Materials). These data confirm that the patient diagnosed with PSP was void of insoluble, aggregated α-synuclein protein.

3.1.2. GBA mutations

Four individuals carried heterozygous GBA mutations, namely p.D448H (n = 2), p.T362I (n = 1), and p.R87Q (n = 1), while one patient (JHND1206) was homozygous for a p.N409S GBA mutation in addition to carrying a LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation as described above. All mutation carriers had parkinsonism on clinical presentation.

3.1.3. APP mutations

Five patients with high-level Alzheimer’s disease pathology were found to have a highly penetrant missense mutation in APP, namely p.V717F (n = 3 patients) and p.V717L (n= 2). One of these five patients also had extensive Lewy body pathology (JHND924, p.V717F).

Furthermore, copy number variant analysis identified three siblings (JHND1189, JHND164, and JHND265) who suffered from early-onset Alzheimer’s disease due to an APP gene duplication. Their clinical presentation was atypical for Alzheimer’s disease, manifesting with prominent but heterogeneous psychiatric and behavioral symptoms in addition to progressive cognitive impairment (see detailed case descriptions in the Supplementary Materials). As a consequence, all three patients were clinically diagnosed with dementia with atypical features rather than Alzheimer’s disease, and the correct diagnosis was only established upon autopsy. This observation is consistent with clinical descriptions of other APP duplication patients that have reported atypical and heterogeneous dementia phenotypes, even within families (Guyant-Marechal et al., 2008; McNaughton et al., 2012).

In all three cases, the duplication encompassed a 3.5 Mb region on chromosome 21, including the entire APP gene. The pathological evaluation of these patients demonstrated high-level Alzheimer’s disease pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. However, one of the three siblings (JHND1189) also had Lewy bodies in his brainstem as well as leukodystrophy with relative sparing of subcortical U-fibers. Leukodystrophy has not been previously reported in patients with Alzheimer’s disease related to duplications including the APP gene, and our observation broadens the pathological phenotype spectrum associated with this mutation. No other causative mutations in known leukodystrophy genes were observed in this patient.

3.1.4. PSEN1 mutations

Five cases with a pathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease were found to carry a pathogenic mutation in PSEN1 (p.T116L, p.M139I, p.I143T, p.R269H, and p.A285B). While four of these patients presented with early-onset dementia, the fifth patient (carrying the p.R269H mutation) manifested with cognitive problems in his late 60s. Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease has been previously reported for this particular mutation and, taken together, these observations suggest reduced penetrance of the p.R269H mutation compared to other PSEN1 missense mutations (Larner et al., 2007). Aside from dementia, several atypical clinical features for Alzheimer’s disease were noted in our PSEN1 cases, including combativeness, dystonia, myoclonus, seizures and gait apraxia that are similar to prior observations (Larner and Doran, 2006).

3.1.5. MAPT mutations

We identified two patients with pathogenic missense mutations in MAPT. One of these patients (JHND1007, p.P301L) presented clinically with behavioral variant FTD, and the patient’s autopsy demonstrated marked accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein consistent with Pick’s disease. This presentation is in line with prior observations of patients carrying this particular mutation (Hutton et al., 1998).

The second patient (JHND92) had low levels of Alzheimer’s disease pathology and carried the p.R5L mutation in exon 1 of the MAPT gene. He had no PSP-like tau inclusions in his brain on autopsy. This particular missense mutation has once been previously reported as disease-causing in a single patient with PSP (Poorkaj et al., 2002). Another missense mutation at the same amino acid (p.R5H) has been reported in a small number of cases, including a sporadic Japanese FTD patient with PSP-like 4-repeat tau deposition on pathological evaluation, a pathologically confirmed Caucasian patient with apparently sporadic PSP, a small Japanese-American family with dementia and ALS without clear segregation, as well as two patients from a Taiwanese family with heterogeneous phenotypes (Hayashi et al., 2002; Leverenz et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2017; Poorkaj et al., 2002). None of these studies screened large control cohorts or demonstrated disease segregation, and it is questionable whether this variant is causally related to the described diseases. The p.R5H variant is present at low frequency in the East Asian population (allele frequency for R5H is 0.0064 according to Genome Aggregation Database). Based on these data the p.R5H mutation should be classified as a variant of unknown significance. Furthermore, most known disease-causing MAPT mutations are within the microtubule binding domains (exons 9 – 13), and only a few disease-causing mutations have been shown to lie outside of these domains. Taken together, the pathogenicity of the p.R5H and p.R5L mutations is questionable.

3.1.6. GRN mutation

We identified one FTD patient (JHND700) with a causative nonsense mutation in GRN (p.R110X). This patient was clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, though her pathology demonstrated severe atrophy of frontal, temporal and parietal lobes. Immunohistochemistry identified TDP-43- and ubiquitin-positive inclusions consistent with a pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

3.1.7. C9orf72 repeat expansion

Hexanucleotide repeat analysis of C9orf72 identified nine cases carrying a pathogenic expansion. Of these, six patients presented clinically with ALS, one case had a clinical presentation consistent with FTD, and two patients had cognitive changes that were clinically thought to be Alzheimer’s disease, but neuropathological evaluations revealed the diagnosis of FTD. The median age at symptom onset was 52 years (range 44 – 69 years). Median survival in patients clinically presenting with ALS was only 3 years (range 1–4 years), whereas patients clinically diagnosed with dementia displayed a longer median survival of 12 years (range 10 – 17 years).

3.1.8. SETX mutations

Three patients with familial ALS carried a pathogenic mutation in SETX. All three patients manifested disease at a young age with slowly progressive motor neuron disease and longer survival (Table 2). This presentation is consistent with prior reports of this rare form of motor neuron disease (Chance et al., 1998).

3.1.9. SPAST mutation

We identified an adult patient with a clinical diagnosis of hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), whose neurological symptoms started in the fourth decade of life. The pathological examination demonstrated marked neurodegeneration of her entorhinal cortex, pons, medulla and spinal cord. Our molecular analysis confirmed the diagnosis by identifying a heterozygous nonsense mutation in SPAST (p.R581X). This particular mutation has been previously reported in an Italian patient with HSP with a similar age at disease onset (Patrono et al., 2005).

3.1.10. CSF1R mutations

Mutations in CSF1R cause a rare, autosomal dominantly inherited neurodegenerative condition called adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (OMIM #221820). We were surprised to identify two cases with a pathogenic CSF1R mutation (p.G589E, and p.M755T) and one case with a likely pathogenic CSF1R mutation (p.L868P). This observation could indicate that this form of leukodystrophy is a more common form of neurodegeneration than previously recognized.

The clinical presentation of two of these patients (JHND1190, and JHND1195) was characterized by early-onset dementia with atypical features, including episodic confusion, seizures, and language impairment. The third case (JHND671) presented clinically with ALS, and this diagnosis was confirmed on autopsy. ALS has not been previously associated with pathogenic mutations in CSF1R. From this single observation, we cannot conclude that a causal relationship between this damaging mutation and ALS exists, but our data nominate CSF1R as a candidate gene that warrants additional exploration.

3.1.11. Copy number variant analysis

Aside from APP duplications described above, copy number variant analysis identified nine cases who carried PARK2 copy number mutations, consisting of six heterozygous duplication carriers and three heterozygous deletion carriers. None of these PARK2 copy number variant carriers were compound heterozygous with other pathogenic mutations in this recessively inherited gene, and these mutations were therefore unlikely to be disease-causing. Copy number variants were not identified in SNCA or PSEN1.

4. Discussion

Here, we describe a genetic evaluation of rare, pathogenic variants in a large cohort of pathologically-confirmed neurodegenerative disease patients obtained from the Johns Hopkins Brain Resource Center. We identified 42 cases (approximately 3.4% of the total cohort) with damaging mutations in diverse neurodegenerative conditions, and we assessed the clinicopathological features of these individuals. This effort demonstrates the power of modern genomic technologies to rapidly screen important sample collections and to unravel the genetic architecture underlying diverse neurodegenerative diseases.

We made several crucial observations. First, our data strongly support the notion that the LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation can present with clinically and pathologically heterogeneous syndromes, including Lewy body diseases, nonspecific nigral neuronal loss and PSP. Limited studies have previously investigated the p.G2019S mutation in PSP cohorts (Gaig et al., 2008; Hernandez et al., 2005; Ruffmann et al., 2012; Sanchez-Contreras et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2006). A prior study identified a p.G2019S mutation in a single PSP case, but it remained unclear if this finding reflected the high prevalence of this mutation in the population or if it was truly disease-causing (Sanchez-Contreras et al., 2017). In contrast, our study strongly argues for a causal relationship between the p.G2019S mutation and PSP. Three out of six LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation carriers had pathological findings consistent with PSP pathological changes without any Lewy body pathology. Furthermore, the pathogenic p.R1441C, p.R1441H, p.T2310M and p.A1413T LRRK2 mutations have been previously reported in PSP patients, providing further support for the notion that LRRK2 mutations rarely cause PSP (Sanchez-Contreras et al., 2017; Spanaki et al., 2006; Trinh et al., 2015). This insight is important and implies that genetic testing for LRRK2 mutations should be more broadly considered in parkinsonism patients with a family history of PSP or Parkinson’s disease to establish a molecular diagnosis. These observations suggest that LRRK2 mutations may have pleiotropic effects and raise the possibility that other genetic and environmental factors are involved in determining the exact phenotypic expressions of LRRK2-related neurodegeneration.

Second, our study highlights the utility of using high-throughput, low-cost genetic screening assays for molecular diagnostic purposes. This application is exemplified by the identification of disease-causing mutations in patients with early-onset dementia syndromes due to CSF1R, PSEN1 or APP mutations. Several of these patients were only correctly diagnosed upon autopsy, or, in the case of CSF1R mutation carriers, the correct diagnosis was only revealed by our genetic analysis. Taken together, we argue that aside from the syndromic description of complex neurodegenerative phenotypes, a molecular genetic characterization of neurodegenerative syndromes should be attempted to correctly diagnose these patients, particularly since genetic screening is becoming more economical. We used the NeuroChip genotyping platform, which is rapid (3-day turn-around), affordable (~$40/sample to screen several hundred thousand variants), and high-throughput (several thousand samples can be analyzed in a well-equipped laboratory each week).

Third, we made several unexpected observations. For example, one patient with a duplication encompassing APP also had leukodystrophy on pathological examination in addition to severe Alzheimer’s disease pathology. We further identified a patient with ALS who carried a likely pathogenic CSF1R mutation. While these single observations do not allow us to draw definite conclusions, they could point toward novel, unrecognized disease associations that should be explored in future research studies.

Finally, another application of comprehensive genetic screening in a well-characterized patient series is that genomic knowledge can provide clarity about questionable pathogenicity labels. An example is the MAPT p.R5L mutation. This mutation has been nominated as disease-causing based on its location within a disease gene (Poorkaj et al., 2002). Another missense mutation at the same amino acid position, p.R5H, has been reported in a few clinically diagnosed neurodegenerative disease cases that lacked clear disease-segregation or screening in controls (Hayashi et al., 2002; Leverenz et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2017). The pathogenicity of mutations at this amino acid position therefore remains unclear. These mutations do not fulfill consensus criteria for pathogenicity based on current knowledge (Richards et al., 2015). The fact that we identified the p.R5L mutation in a case without any tau pathology also argues against a pathogenic role of this coding variant and suggests that this mutation should be reclassified as a variant of unknown significance. This information is important for counseling of individuals carrying this variant, as genetic data do not conclusively demonstrate a pathogenic role of the p.R5L missense mutation.

5. Conclusion

Progress of molecular genomics technologies provides novel opportunities to gain critical insights into complex neurodegenerative syndromes. Although Mendelian forms of neurodegeneration only comprise a small proportion of the neurodegenerative disease population, defining molecular defects in these individuals reveals crucial phenotype correlations and clinical knowledge that allows for improved counseling of patients carrying pathogenic variants, and for studying the functional consequences leading to neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Genetic screening arrays provide novel opportunities to study neurodegeneration.

Pathogenic mutation carriers can present with clinicopathological heterogeneity.

We highlight the utility of high-throughput arrays for molecular diagnostics.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who donated nervous tissue for scientific research. Funding: This work was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging; projects ZIA-NS003154 and Z01-AG000949). This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health: U19-AG03365, P50 NS38377 and P50-AG005146. Samples: Tissue samples for genotyping were provided by the Johns Hopkins Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research (NIH P50 NS38377) and the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. We are grateful for the support of the entire BIOCARD study team at Johns Hopkins University. Additionally, we acknowledge the contributions of the Geriatric Psychiatry Branch (GPB) in the intramural program of NIMH who initiated the BIOCARD study. We would like to thank the NIA Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging for contributing tissue samples to the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Computational support: This study used the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (http://biowulf.nih.gov). Faraz Faghri’s contribution to this work has been supported in part through the grant 1U54GM114838 awarded by NIGMS through funds provided by the trans-NIH big data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative (www.bd2k.nih.gov). Dr. Dawson is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Disease. We would like to thank members of the International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC; pdgenetics.org) and the COURAGE-PD Consortium for curating the custom content of the NeuroChip.

Verification statements

Dr. Michael A. Nalls’ participation is supported by a consulting contract between Data Tecnica International LLC and the National Institute on Aging, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA. Dr. Nalls also consults for Illumina Inc, the Michael J. Fox Foundation and Vivid Genomics. None of the other authors declare any possible conflicts of interest.

Funding: This work was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute on Aging; projects ZIA-NS003154 and Z01-AG000949). This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health: U19-AG03365, P50 NS38377 and P50-AG005146. Samples: Tissue samples for genotyping were provided by the Johns Hopkins Morris K. Udall Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease Research (NIH P50 NS38377) and the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

The data contained in this manuscript have not been previously published and will not be submitted elsewhere while under consideration at Neurobiology of Aging.

All authors reviewed the contents of the submitted manuscript, approve of its contents and validate the accuracy of the data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Please see attached Supplementary Table and Supplementary Materials.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR, 2010. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods 7(4), 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwendraat C, Faghri F, Pihlstrom L, Geiger JT, Elbaz A, Lesage S, Corvol JC, May P, Nicolas A, Abramzon Y, Murphy NA, Gibbs JR, Ryten M, Ferrari R, Bras J, Guerreiro R, Williams J, Sims R, Lubbe S, Hernandez DG, Mok KY, Robak L, Campbell RH, Rogaeva E, Traynor BJ, Chia R, Chung SJ, International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics, C., Consortium, C.-P., Hardy JA, Brice A, Wood NW, Houlden H, Shulman JM, Morris HR, Gasser T, Kruger R, Heutink P, Sharma M, Simon-Sanchez J, Nalls MA, Singleton AB, Scholz SW, 2017. NeuroChip, an updated version of the NeuroX genotyping platform to rapidly screen for variants associated with neurological diseases. Neurobiol. Aging [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance PF, Rabin BA, Ryan SG, Ding Y, Scavina M, Crain B, Griffin JW, Cornblath DR, 1998. Linkage of the gene for an autosomal dominant form of juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to chromosome 9q34. Am. J. Hum. Genet 62(3), 633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ, 2015. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov EV, Goode DL, Sirota M, Cooper GM, Sidow A, Batzoglou S, 2010. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++. PLoS Comput. Biol 6(12), e1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs J, Nilsson C, Kachergus J, Munz M, Larsson EM, Schule B, Langston JW, Middleton FA, Ross OA, Hulihan M, Gasser T, Farrer MJ, 2007. Phenotypic variation in a large Swedish pedigree due to SNCA duplication and triplication. Neurology 68(12), 916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaig C, Ezquerra M, Marti MJ, Valldeoriola F, Munoz E, Llado A, Rey MJ, Cardozo A, Molinuevo JL, Tolosa E, 2008. Screening for the LRRK2 G2019S and codon-1441 mutations in a pathological series of parkinsonian syndromes and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J. Neurol. Sci 270(1–2), 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyant-Marechal I, Berger E, Laquerriere A, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Viennet G, Frebourg T, Rumbach L, Campion D, Hannequin D, 2008. Intrafamilial diversity of phenotype associated with app duplication. Neurology 71(23), 1925–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Toyoshima Y, Hasegawa M, Umeda Y, Wakabayashi K, Tokiguchi S, Iwatsubo T, Takahashi H, 2002. Late-onset frontotemporal dementia with a novel exon 1 (Arg5His) tau gene mutation. Ann. Neurol 51(4), 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA, 2013. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 80(19), 1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D, Paisan Ruiz C, Crawley A, Malkani R, Werner J, Gwinn-Hardy K, Dickson D, Wavrant Devrieze F, Hardy J, Singleton A, 2005. The dardarin G 2019 S mutation is a common cause of Parkinson’s disease but not other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosci. Lett 389(3), 137–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P, 1998. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393(6686), 702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, Guturu H, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, Bernstein JA, Bejerano G, 2016. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat. Genet 48(12), 1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J, 2014. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet 46(3), 310–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N, 1998. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392(6676), 605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksovirta H, Peuralinna T, Schymick JC, Scholz SW, Lai SL, Myllykangas L, Sulkava R, Jansson L, Hernandez DG, Gibbs JR, Nalls MA, Heckerman D, Tienari PJ, Traynor BJ, 2010. Chromosome 9p21 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Finland: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 9(10), 978–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larner AJ, Doran M, 2006. Clinical phenotypic heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease associated with mutations of the presenilin-1 gene. J. Neurol 253(2), 139–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larner AJ, Ray PS, Doran M, 2007. The R269H mutation in presenilin-1 presenting as late-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci 252(2), 173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG, Exome Aggregation C, 2016. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536(7616), 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverenz J, Bird T, Rumbaugh M, Yu C-E, Cruchaga C, Steinbart E, Ravits J, Leverenz J, 2011. Is the Arg5His MAPT variant pathogenic for dementia and motor neuron disease? Alzheimers Dementia(7), S202–S203. [Google Scholar]

- Lin HC, Lin CH, Chen PL, Cheng SJ, Chen PH, 2017. Intrafamilial phenotypic heterogeneity in a Taiwanese family with a MAPT p.R5H mutation: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 17(1), 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucking CB, Abbas N, Durr A, Bonifati V, Bonnet AM, de Broucker T, De Michele G, Wood NW, Agid Y, Brice A, 1998. Homozygous deletions in parkin gene in European and North African families with autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. The European Consortium on Genetic Susceptibility in Parkinson’s Disease and the French Parkinson’s Disease Genetics Study Group. Lancet 352(9137), 1355–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarin M, Simon-Sanchez J, Fung HC, Scholz S, Gibbs JR, Hernandez DG, Crews C, Britton A, De Vrieze FW, Brott TG, Brown RD Jr., Worrall BB, Silliman S, Case LD, Hardy JA, Rich SS, Meschia JF, Singleton AB, 2008. Structural genomic variation in ischemic stroke. Neurogenetics 9(2), 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton D, Knight W, Guerreiro R, Ryan N, Lowe J, Poulter M, Nicholl DJ, Hardy J, Revesz T, Lowe J, Rossor M, Collinge J, Mead S, 2012. Duplication of amyloid precursor protein (APP), but not prion protein (PRNP) gene is a significant cause of early onset dementia in a large UK series. Neurobiol. Aging 33(2), 426 e413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S, 2003. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 31(13), 3812–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H, 2014. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Current Population Reports: United States Census Bureau, pp.1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Patrono C, Scarano V, Cricchi F, Melone MA, Chiriaco M, Napolitano A, Malandrini A, De Michele G, Petrozzi L, Giraldi C, Santoro L, Servidei S, Casali C, Filla A, Santorelli FM, 2005. Autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia: DHPLC-based mutation analysis of SPG4 reveals eleven novel mutations. Hum. Mutat 25(5), 506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P, Muma NA, Zhukareva V, Cochran EJ, Shannon KM, Hurtig H, Koller WC, Bird TD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Schellenberg GD, 2002. An R5L tau mutation in a subject with a progressive supranuclear palsy phenotype. Ann. Neurol 52(4), 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput A, Dickson DW, Robinson CA, Ross OA, Dachsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Cobb SA, Rajput ML, Farrer MJ, 2006. Parkinsonism, Lrrk2 G2019S, and tau neuropathology. Neurology 67(8), 1506–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, Kalimo H, Paetau A, Abramzon Y, Remes AM, Kaganovich A, Scholz SW, Duckworth J, Ding J, Harmer DW, Hernandez DG, Johnson JO, Mok K, Ryten M, Trabzuni D, Guerreiro RJ, Orrell RW, Neal J, Murray A, Pearson J, Jansen IE, Sondervan D, Seelaar H, Blake D, Young K, Halliwell N, Callister JB, Toulson G, Richardson A, Gerhard A, Snowden J, Mann D, Neary D, Nalls MA, Peuralinna T, Jansson L, Isoviita VM, Kaivorinne AL, Holtta-Vuori M, Ikonen E, Sulkava R, Benatar M, Wuu J, Chio A, Restagno G, Borghero G, Sabatelli M, Consortium I, Heckerman D, Rogaeva E, Zinman L, Rothstein JD, Sendtner M, Drepper C, Eichler EE, Alkan C, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Dutra A, Pak E, Hardy J, Singleton A, Williams NM, Heutink P, Pickering-Brown S, Morris HR, Tienari PJ, Traynor BJ, 2011. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72(2), 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee ALQA, 2015. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med 17(5), 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, Le Meur N, Laquerriere A, Vital A, Dumanchin C, Feuillette S, Brice A, Vercelletto M, Dubas F, Frebourg T, Campion D, 2006. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat. Genet 38(1), 24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffmann C, Giaccone G, Canesi M, Bramerio M, Goldwurm S, Gambacorta M, Rossi G, Tagliavini F, Pezzoli G, 2012. Atypical tauopathy in a patient with LRRK2-G2019S mutation and tremor-dominant Parkinsonism. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 38(4), 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Contreras M, Heckman MG, Tacik P, Diehl N, Brown PH, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Christopher EA, Walton RL, Ross OA, Golbe LI, Graff-Radford N, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW, Rademakers R, 2017. Study of LRRK2 variation in tauopathy: Progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Mov. Disord 32(1), 115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K, 2003. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science 302(5646), 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Kwok JB, McLean CA, Kril JJ, Broe GA, Nicholson GA, Cappai R, Hallupp M, Cotton RG, Masters CL, Schofield PR, Brooks WS, 2001. Variable phenotype of Alzheimer’s disease with spastic paraparesis. Ann. Neurol 49(1), 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanaki C, Latsoudis H, Plaitakis A, 2006. LRRK2 mutations on Crete: R1441H associated with PD evolving to PSP. Neurology 67(8), 1518–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DL, Tayebi N, Orvisky E, Stubblefield B, Madike V, Sidransky E, 2000. Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations in patients with type 2 Gaucher disease. Hum. Mutat 15(2), 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EK, Skipper L, Chua E, Wong MC, Pavanni R, Bonnard C, Kolatkar P, Liu JJ, 2006. Analysis of 14 LRRK2 mutations in Parkinson’s plus syndromes and late-onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord 21(7), 997–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh J, Guella I, McKenzie M, Gustavsson EK, Szu-Tu C, Petersen MS, Rajput A, Rajput AH, McKeown M, Jeon BS, Aasly JO, Bardien S, Farrer MJ, 2015. Novel LRRK2 mutations in Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord 21(9), 1119–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H, 2010. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(16), e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.