Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a significant health concern rooted in community experiences and other social determinants. The purpose of this study is to understand community-based risk and protective factors of IPV perpetration through participatory research that engages men who use IPV. Secondarily, we assess the relative influence, as measured by ranking, of these factors regarding risk of IPV perpetration and stress. We conducted concept mapping with Baltimore men (n = 28), ages 18 and older, enrolled in an abuse intervention program (AIP), through partnership with a domestic violence agency. Concept mapping, a three-phase participatory process, generates ideas around an issue then visually presents impactful domains via multi-dimensional scaling and hierarchical clustering. Most participants were Black (87.5%) and 20–39 years old (75%). Seven key domains, or clusters, were established. “No hope for the future” was the greatest contributor to IPV perpetration. “Socioeconomic struggles” (i.e., lack of employment) and “life in Baltimore” (i.e., homicide) were most likely to result in stress. Emergent domains related to IPV perpetration and stress were ranked similarly, but with some nuance. Having good support systems (i.e., family, community centers) were felt to prevent IPV and reduce stress. This participant-driven process among a primarily young, Black sample of Baltimore men speaks to the influence of perceived social disempowerment and underlying trauma on intimate relationships and the potential for mitigation. Few studies have engaged men who use IPV through participatory research to understand the comprehensive dynamics of an impoverished, urban environment. Results provide direction for community-based intervention and prevention programming to increase self-efficacy, particularly among younger men, and to enact trauma-informed violence prevention policy from the perspectives of male IPV perpetrators.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, Violence perpetration, Social determinants, Urban health, Concept mapping, Men, Participatory research

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive public health issue. Approximately 36% of US women have experienced IPV in their lifetime, with an elevated lifetime prevalence among Black (44%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (46%), and multiracial (54%) minority groups [1]. IPV victimization among women, relative to men, is often more severe and likely to consist of multiple forms of abuse, including sexual violence [1–3]. Poor physical [1, 4], psychological [4–6], sexual [7], reproductive [8], and social health are associated with IPV [9, 10], especially for women. The outcomes of IPV are well documented, yet little information about IPV perpetration has been gathered from the perspectives of men, and very little is known about how community factors influence IPV risk.

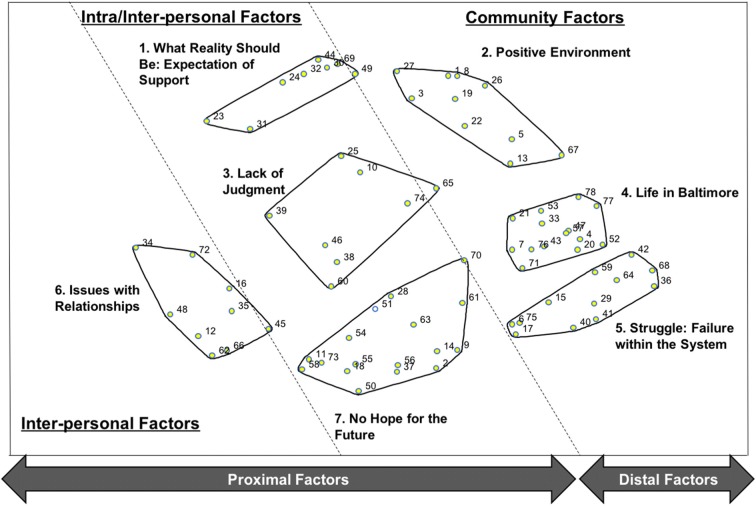

Violence perpetration has multiple roots, including men’s past experiences with violence perpetration and victimization through community and family-based exposure and stress [11–17]. Urban environments like Baltimore, MD, house a myriad of socio-structural factors that increase the risk of violence [16], including homicides and other forms of street violence that are often a priority of prevention [15, 18–20]. Given the complexity of violence, identified risk factors have emerged at multiple levels of the socio-ecological framework [21], with violence among men associated with use of violence in intimate relationships [15, 22–26]. Socio-ecological factors such as adverse childhood experiences, witnessing abuse as a child, cultural norms related to manhood and acceptability of violence, and participating in community violence have been linked to IPV perpetration among men in adulthood [15, 22–26]. Central to violence perpetration is the construct of stress, also associated with community-driven factors such as discrimination [27–29], neighborhood disorder [30], and other neighborhood related stressors like fighting for survival [28, 31], criminal justice involvement [32, 33], neighborhood poverty [34–37], and individual financial strain [36–38] (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, a clear mechanistic understanding of how experiences in urban environments contribute to or prevent IPV perpetration has yet to be established [20].

Fig. 1.

The influence of community-level risk factors on IPV perpetration and stress [27–38]

At the intra- and interpersonal levels of the socio-ecological framework, early experiences of violence during childhood and adolescence among men are associated with increased risk for perpetrating street violence and IPV [11, 12]. While women are likely to experience violence from an intimate partner, men are more likely to be a victim of violence perpetrated by a stranger or acquaintance, which, in turn, increases their odds of using IPV [13–15]. At the community level, community violence and social norms that promote gendered power dynamics increase male perpetrated abuse [25, 31, 39]. Peitzmeier and colleagues [31] explored the impact of recent community violence victimization among a sample of adolescent men from four disadvantaged cities in North America, Asia, and Africa (Baltimore, USA; Delhi, IN; Johannesburg, ZA; Shanghai, CN). Young men victimized by past-year community violence in Johannesburg, Delhi, and Baltimore were more likely to perpetrate IPV within this timeframe; however, the effect was much greater among men in Baltimore (OR = 7.00) compared to men in Johannesburg (OR = 2.82) and Delhi (OR = 4.08), seeming to suggest greater community influence in Baltimore given the variance across sites [31]. Among a sample of young Black men, ages 18–29, attitudes favorable of IPV perpetration were mediated by neighborhood violence and poor conflict resolution among intimate partners [40].

The influence of community context on IPV perpetration through factors including violence and social norms that favor violence against women (VAW) has been established by existing research [20, 24, 31, 39, 40]. However, despite this evidence implicating community-level factors in IPV perpetration, very few studies have engaged male perpetrators of IPV in an effort to understand the comprehensive dynamics of an impoverished, urban environment. Furthermore, specific community attributes that contribute to male perpetration of IPV are not widely present in the literature perhaps due to challenges in recruiting this population for research [41]. To date, many of the research studies conducted among male IPV perpetrators have been grounded in the clinical psychology and criminology disciples and have focused on factors such as mental health and recidivism [42–45]. The current study is unique in that it explores community-based influences of male IPV perpetration.

Engaging male IPV perpetrators to understand partner violence from their perspective is essential in learning how best to support them in optimal IPV prevention and intervention efforts and address potential underlying trauma and disempowerment. This is the first study to engage adult men to explore the role of community context and characteristics that may promote or prevent male perpetration of IPV and experiences of stress. The current study provides insight into the associations of community factors and IPV established in previous epidemiological research by engaging the voices of IPV perpetrators. We used a community engaged research approach, which included partnership with a community organization and a participatory research method to explore experiences of male IPV perpetrators participating in an abuse intervention program (AIP).

Materials and Methods

Setting and Participation

We conducted concept mapping in Baltimore, MD, with male participants of an AIP at a local domestic violence agency between June 2016 and March 2017. Baltimore is nationally known for its high incidence of violence and socio-structural barriers (i.e., institutional racism, neighborhood blight) that negatively influence health and behavior [19, 46–48]. The domestic violence agency is strategically placed within Baltimore City, allowing for service provision to members of Baltimore City and the surrounding area.

Eligible participants were 18 years of age and older, residents of Baltimore City or Baltimore County, and current or recent participants of an AIP. The research team, including agency staff members, used active (in-person) and passive (posting flyers) recruitment methods at the AIP site. We intentionally recruited AIP enrollees to ensure that participants were accustomed to participating in meaningful discussions about IPV. These procedures generated a total of 28 male participants from the AIP across the three phases of concept mapping. Overall, 57% of participants (16/28) participated in at least two of three concept mapping phases.

Concept Mapping Procedures

Concept mapping is a participatory research method that utilizes qualitative and quantitative methods to visually display primary domains of a given topic [49, 50]. Our application of concept mapping included three, sequential phases, brainstorming, sorting and rating, and participant interpretation, that work to integrate the ideas of multiple people through statistically rigorous, hierarchical mapping [51–55]. Male IPV perpetration was the primary focus of these concept mapping activities, with stress that men experience added as a secondary focus to the rating exercise only. We chose concept mapping for the richness of data it provides qualitatively and its participatory nature to engage a hard to reach population [55].

All activities were conducted in collaboration with a comprehensive domestic violence agency that offers support to IPV survivors including housing, legal support, counseling, and AIPs for both men and women. The concept mapping focal prompt development and participant recruitment protocol were conducted collaboratively between the domestic violence agency and the research members from Johns Hopkins University. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved all data collection procedures.

Phase 1: Brainstorming

We convened eight brainstorming group discussions with a total of 21 participants, averaging three participants per discussion, and lasting approximately 60 to 120 min each. Participants responded individually on paper and then as a group to the following prompt: “List things about your community, good or bad, that could cause an abusive situation between a man and his intimate partner or prevent one from happening.” Descriptions of the terms “community,” “intimate partner,” and “abuse” were provided to ensure that participants across groups shared the same understanding of these terms to minimize confounding. “Community” was defined as anywhere they live, work, or socialize. An “intimate partner” was broadly defined as a spouse, boyfriend/girlfriend, casual dating or sex partner, or co-parent. “Abuse” encompassed physical, psychological, and sexual/reproductive abuse as well as stalking or threatening harm.

Participants were given 15 min to brainstorm individually regarding the prompt, and the remaining time was used for audio-recorded group discussion. During group discussion, participants shared their respective responses, which were posted by the research team on easel paper in real-time, and the research team asked for clarification when needed. Group sharing facilitated some discussion about responses and the generation of new ideas. Researchers collected lists from individual and group brainstorming at the end of each discussion to ensure that all responses were captured and later compiled the responses in a spreadsheet (n = 354). Once saturation was met, after eight discussions, duplicate brainstorming items were removed, and remaining items were consolidated by the research team when appropriate or discarded (n = 53) when deemed to be out of scope for the current study (e.g., “Women just into sex and drugs, wearing revealing clothing […]”). This process generated a final set of 78 items for the sorting and rating activity.

Phase 2: Sorting and Rating

Nine sorting and rating groups were held with 24 participants, also lasting 60 to 120 min. Participants were asked to complete two tasks: manual sorting and rating of the 78 items generated in the first phase. For sorting, participants grouped the statements that were each listed on an individual card, in a way that made sense to them. They labeled the resulting piles accordingly. Participants then rated the list of items relative to IPV perpetration and male stress, respectively, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = does not contribute and 5 = strongly contributes). The IPV perpetration rating prompt was (1) “How strongly do you think each of the items listed below would influence the likelihood that abuse will happen between a man and his intimate partner?” and the stress rating prompt was (2) “How strongly does each item increase the level of stress that men experience?”

Participant sorting and rating data were inputted and analyzed using Concept Systems Global Max [56]. Namely, multi-dimensional scaling and hierarchical clustering were used to generate the concept maps around IPV perpetration, identifying primary themes related to the phase 1 focal prompt. The final cluster solution (n = 7) was determined by the research team and presented to participants for approval. The arrangement of clusters and points within the map are relative—the closer the cluster or point, the stronger the relationship. Spanning analyses gauged the level of cluster and point-specific bridging or connection on a scale from 0 to 1. A higher bridging score for a statement indicates greater disagreement in the participants’ sorting results, with scores closer to 0 indicating greater likelihood of participant agreement. Average cluster ratings were calculated to determine the participants’ perceived influence of each cluster on IPV perpetration and stress, respectively, using the rating data for each of the 78 items. These ratings were averaged by cluster with regard to IPV perpetration and stress and presented via pattern matching. Pattern matching is a visual, pairwise comparison that demonstrates the relative influence of rating variables on a particular outcome.

Phase 3: Generation and Participant Interpretation of Concept Map

Ten interpretive discussions about the resulting concept map were conducted with 16 participants for 60 to 90 min each. Each discussion began with the research team describing the concept map and the contents within each cluster. Participants were then asked to work individually or collaboratively to describe their interpretation of the concept map, illustrating the relationships of clusters overall as well as factors within each cluster, and to suggest changes for cluster merging or re-location of outlying points. Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed and used by the research team to understand nuances of the concept map.

Results

Participant Characteristics of the Sorting and Rating Phase

Participants were primarily Black (87.5%), 20–39 years old (75%), and single (58%). Nearly 40% of participants earned less than $10,000 per year. Education varied, with a third of participants having completed some high school and nearly a third having attended college. Finally, most (75%) participants were in stage 2 of the AIP, indicating their willingness to accept responsibility for their abusive behavior (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of men who participated in sorting and rating (n = 24)

| Characteristic | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–29 | 46 (11) |

| 30–39 | 29 (7) |

| 40–49 | 16 (4) |

| 50 and older | 8 (2) |

| Race | |

| White | 4 (1) |

| Black | 88 (21) |

| Other | 8 (2) |

| Individual income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 38 (9) |

| $10,000–$29,999 | 29 (7) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 29 (7) |

| $50,000 or more | 4 (1) |

| Employment | |

| Student | 4 (1) |

| Employed | 71 (17) |

| Unemployed/disabled | 25 (6) |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 33 (8) |

| High school graduate | 38 (9) |

| Some college | 13 (3) |

| College graduate | 17 (4) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 58 (14) |

| Married | 8 (2) |

| Serious relationship (not married) | 21 (5) |

| Dating more than one person | 4 (1) |

| Divorced | 8 (2) |

| Country or origin | |

| US born | 92 (22) |

| Foreign born | 8 (2) |

| AIP intervention stage | |

| Stage 1 | 21 (5) |

| Stage 2 | 75 (18) |

| No response | 4 (1) |

| Intimate partner violence perpetration (lifetime)* | |

| Hit, slapped, kicked, punched, pushed, chocked, or used other physical harm | 54 (13) |

| Grabbed, shook, or slammed partner against a wall | 54 (13) |

| Insulted or swore at partner | 71 (17) |

| Reproductive coercion perpetration (lifetime)* | |

| Made partner have sex without a condom or removed condom during sex | 0 (0) |

| Used deception to get partner pregnant | 8 (2) |

Demographic characteristics of men who participated in phase 2: sorting and rating

*Denotes row percentages. All other categories are column percentages

Community Characteristics by Clusters

The participant-generated list of 78 statements about community characteristics associated with men’s perpetration of IPV (Table 2) includes both risk and protective factors related to IPV (i.e., presence of drugs/alcohol in one’s community and community centers for youth, respectively). In addition to addressing community resources, participants listed interpersonal experiences (i.e., witnessing IPV during childhood) and social influences (i.e., social media) in response to the focal question.

Table 2.

Overview of clusters and cluster statements that correspond with the concept map

| Cluster | Statement name (number) |

|---|---|

| 1. What reality should be: expectation of support | |

| Social standards (going to college, marriage, buying a home) (23) | |

| Having open family talks (24) | |

| Positive influence by friends/peers (30) | |

| Feelings of hope (31) | |

| Positive support from parents/parents teaching right from wrong (32) | |

| Positive family influence (44) | |

| Positive family activities in the community (e.g., community cookouts) (49) | |

| People support one another (69) | |

| 2. Positive environment | |

| Community centers for youth (1) | |

| Having access to activities that relieve stress (e.g., boxing and other sports, restaurants, etc.) (3) | |

| A shortage of programs that teach about healthy relationships (5) | |

| Having community resources (e.g., YO! Baltimore, safe streets, living classroom) (8) | |

| Community teaches lack of respect for self and other gender (13) | |

| Blocks getting news houses (19) | |

| What one experiences in the Baltimore County environment (e.g., Towson) (22) | |

| Having neighborhood stores (26) | |

| Positive mentors for youth (27) | |

| Some cops are good (67) | |

| 3. Lack of judgment | |

| Reality T.V. (10) | |

| Religious beliefs (25) | |

| Perceived racism (38) | |

| Partners have different opinions about issues in the community (39) | |

| Lack of positive parent role models (46) | |

| Porn (60) | |

| Social media (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram) (65) | |

| Idolizing/looking up to lifestyles or images presented in the media (74) | |

| 4. Life in Baltimore | |

| Neighborhood has abandoned houses and dirty streets (4) | |

| Lack of access to mental health, medical care, or counseling (7) | |

| A lot of drugs/alcohol available in the community (20) | |

| Jealous people in my community (21) | |

| Bad school system (33) | |

| Unsafe neighborhoods (43) | |

| A lot of killings/violence in my community (47) | |

| A lot of guns are available (52) | |

| Kids don’t have anything to do (53) | |

| lack of job opportunities (57) | |

| People are used to seeing violence in the community (71) | |

| Beefing between Black brothers (men) (76) | |

| What one experiences in the Baltimore City environment (77) | |

| Lack of community resources (e.g., re-entry programs, schools, community centers) (78) | |

| 5. Struggle: failure within the system | |

| Lack of money for food, children’s needs, etc. (6) | |

| Incarceration of male figures (15) | |

| Hustling to get money (17) | |

| Lack of access to a lawyer of choice (29) | |

| Strict sentencing in Maryland (36) | |

| Lack of trust in police (40) | |

| The negative effects of lead poisoning (41) | |

| Abuse or fear of abuse from police officers (42) | |

| Reputation of aggression in Baltimore (59) | |

| Anger/tension experienced by community members and police from current issues in community (64) | |

| Police do what they want (i.e., illegal stopping and searching) (68) | |

| Dealing drugs (75) | |

| 6. Issues with relationships | |

| Trust issues in intimate relationships (12) | |

| Being labeled as an abuser (16) | |

| One partner makes more money than the other (34) | |

| Negative family influence that causes conflict (35) | |

| Feeling powerless or voiceless (45) | |

| Differences in sexual expectations between partners (48) | |

| Cheating on partner (62) | |

| Acceptance of intimate partner violence (66) | |

| Inability to provide for family (72) | |

| 7. No hope for the future | |

| Not having a father figure (2) | |

| Having no plan for the future/no vision (9) | |

| Feeling frustrated from life experiences (anger) (11) | |

| Not having a family (14) | |

| No knowledge of how to treat an intimate partner (18) | |

| Lack of outlets or ways to cope with issues (28) | |

| Not experiencing love as a child (37) | |

| One or both partners use drugs (50) | |

| Negative childhood experiences (51) | |

| Fear of stopping violence (54) | |

| Major stress (e.g., physical, mental, emotional stress) (55) | |

| Seeing domestic violence during childhood (56) | |

| Feeling like everyone is out to get you (58) | |

| Most people want to be a hood star (61) | |

| Negative influence by friends/peers that causes conflict (63) | |

| Music makes bad things sound acceptable (e.g., disrespect of women, killing) (70) | |

| Not caring for self or others (73) |

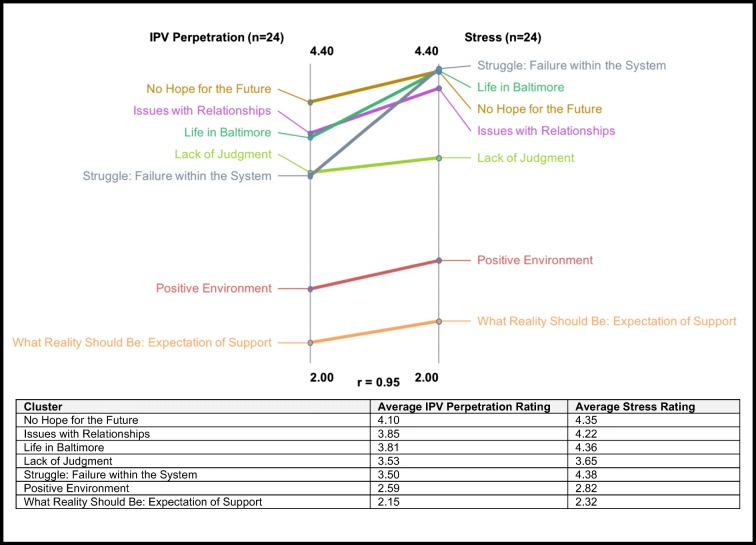

A final seven-cluster solution was selected and labeled based on participants’ sorting and rating data and qualitative interpretation of results (Fig. 2). Cluster 1 (what reality should be: expectation of support) encompasses support from family, peers, and community members and cluster 2 (positive environment) is centered on community resources as measures of prevention. In cluster 3 (lack of judgment), participants highlight media and other social influences on IPV perpetration. Clusters 4 (life in Baltimore) and cluster 5 (struggles: failure within the system) describe life in Baltimore with some degree of distinction between clusters—during the interpretation phase, some participants opted to combine these two clusters, but this suggestion did not fit the consensus of the larger group. Finally, cluster 6 (issues within relationships) describes factors such as infidelity and other challenges that occur within an intimate relationship, and cluster 7 (no hope for the future) describes interpersonal risk factors such as a negative family infrastructure (e.g., not having a family, #14).

Fig. 2.

Final cluster map (n = 7) showing community influences on male partner violence perpetration in relation to the socio-ecological model. The 78 statements that were generated, sorted, and rated by the participants comprise the clusters and are indicated by numbered points on the map. See Table 2 for the list of statements and corresponding point numbers. Cluster labels were created using suggestions from participants

Upon visual inspection of the clusters and proximity of points therein, participants noted a clear delineation between the top and bottom regions of the map. Cluster 1 (what reality should look like: expectation of support), such as positive influence by friends/peers (#30) and cluster 2 (positive environment), community centers for youth (#1) highlight positive factors that may prevent incidents of IPV. These clusters are polarized at the top of the map. The remaining clusters containing statements about negative community characteristics and common experiences of this population are in the lower region (Fig. 2).

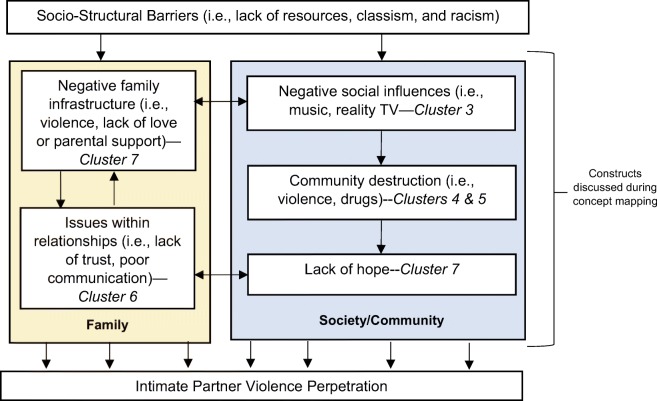

Relative Influence: Impacts on IPV Perpetration and Stress

Pattern matching showed similar influence of the emergent themes on IPV perpetration and stress, but with some nuance regarding clusters in the lower region of the cluster map (Fig. 3). In the upper region of the cluster map, cluster 1 (what reality should be: expectation of support) and cluster 2 (positive environment) were consistently ranked low as contributors to IPV perpetration and stress among abusive men on the pattern match scale. Cluster 7 (no hope for the future) was most likely to facilitate IPV between a man and his intimate partner. Cluster 5 (struggles: failure within the system) was most attributed to stress that men experience. Participants ranked individual points within cluster 7, major stress (e.g., physical, mental, emotional stress, #55), and seeing domestic violence during childhood (#56), as the top two greatest contributors of both IPV perpetration and stress that men experience.

Fig. 3.

Cluster rating results by likelihood of enabling IPV perpetration (1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely) and contributing to stress that men experience (1 = does not contribute to 5 = strongly contributes)

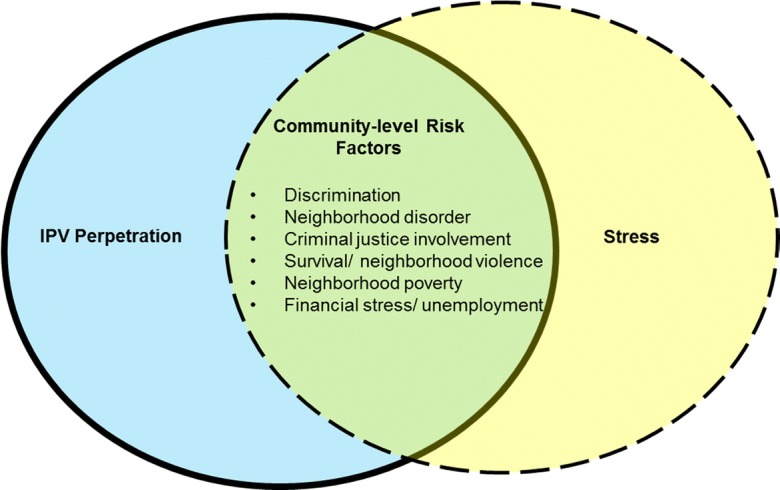

Participant Reflection and Cluster Pathway Analysis

Participants provided detailed interpretations of the cluster map as well as insights into the collective relationships of all the items and clusters (Fig. 4). Socio-structural risk factors such as lack of resources and classism were described as the foundation of family-based and social/community risk factors and were the primary foci of the interpretation. One participant contextualized the processes of the concept map, “So, I think that community disorganization is going to lead to economic exploitation and psychological violence, and that leads to no hope for the future.” Additionally, family-based experiences such as not receiving love as a child negatively impacted participants’ ability to hold a healthy relationship, “Because how do you love someone else if you cannot love yourself first? It’s impossible. You don’t even know what love is, you never had it”. In the absence of positive parental influence, destructive social influences become adopted and exacerbate disorganization within a community, ultimately leading to a lack of hope.

Fig. 4.

The participants’ description of pathways within the final cluster map

Family Influence on IPV Perpetration

Participants described cluster 7 (no hope for the future) as “the root of domestic violence”. “This is how a lot of domestic violence starts and how it ends.” Discussion of cluster 7 was centered on parental neglect and modeling of adverse behavior (i.e., IPV, drug use) resulting in participants’ frustration, hardening, and misconstrued perceptions of how to love (i.e., not caring for self or others, #73); “As you get older you may be angry in situations, you bring it home, you start fighting with you partner, not even knowing you actually saw it [IPV] as a child”. Participants further discussed “…people can’t get over their past [e.g., molestation, child abuse] and they apply it to relationship issues because they’re hurt really bad. Hurt people hurt people…” and, “if you have no respect for yourself, then how you going to have respect for a woman or anyone else in the community?” These statements demonstrate the connection between clusters 6 (issues with relationships) and 7.

Established Gender Norms through Media and Peer Influence

A negative family infrastructure not only impacted intimate relationships but was directly connected to social/community-oriented risk factors. Participants noted a direct link between cluster 7 and challenges within their intimate partnership (cluster 6) with societal/community influences. Namely, a lack of parental influence increased the men’s vulnerability to adopt the maladaptive norms displayed in the media (cluster 3: lack of judgment) and via older peers—“I had a good father, good mother, but at the end of the day the streets captured me. And, because my father was never around, he was at work, you know? I needed a male role model in my life. And, I went to the streets to find it […] I let the streets influence how I should be acting in my household. I started treating my lady from what I got off the streets, and that shit got me locked up.”

Cluster 3 generated discussion of factors that were most highly ranked as contributors to IPV perpetration and stress (e.g., reality TV, #10, idolizing/looking up to lifestyles in the media, #74, social media, #65). These factors normalize negative behaviors that are replicated especially among youth, such as using VAW and violence in general and drugs and alcohol. “Music makes bad things sound acceptable; disrespecting women, killing, even our local artists. That’s pretty much beaten into our heads from the moment we wake up in the morning [...] You ride the bus and hear kids ‘blah, blah, blah’. It’s drilled into your brain as acceptable when it’s really not.” Another man described unrealistic fantasies brought on through media, “A lot of females think it’s going to be like a movie. It’s never like a movie […] People don’t realize that they live off and feed off TV and social media.” Alternatively, in one discussion, religion was discussed as an escape from the remaining social influences captured in this cluster, and social media was discussed in two groups as a tool to educate communities and provide positive peer support for perpetrators of IPV. Nonetheless, the influence of media was primarily damaging rather than constructive and shapes everyday life in Baltimore.

Socio-structural Risk Factors

Cluster 4 (life in Baltimore) and cluster 5 (struggle: failure with the system) were interpreted to comprise destructive characteristics or “community disorganization” that people see in Baltimore, primarily driven by poverty due to lack of employment opportunities, bad school systems, poor mental health, and other socio-structural factors like marginalization of low-income communities through displacement, police brutality, and incarceration. “I am not going to sit here and say that a lot of people don’t deserve to be in jail, but throwing people in jail doesn’t always help because only animals belong in cages, and that’s pretty much what you are telling me […] you want to send me to jail because I’m not worth being helped.” Such disorganization was also attributed to social influence like music that normalizes violence and drug dealing and can over-power positive family influence as described by one participant; “people want to see you not do good.” Another participant described the influence of socio-structural beings on masculinity and perpetration of sexual violence. “I think a lot of poor; low-income men see sex as an outlet. It’s a way to, I think it’s a compensatory behavior. Compensation for feeling emasculated because you can’t get a job or because your boss cusses you out every day.” Ultimately, these socio-structural influences culminate in a lack of hope or disempowerment (cluster 7).

Discussion

This study contextualizes community risk and protective factors of IPV perpetration among a relatively homogenous sample of young, urban Black men. Lack of hope was quantitatively and qualitatively captured by male IPV perpetrators as the root of partner violence, exacerbated by poor behavior modeling within families and parental neglect. A lack of positive parental influence coupled with community disorganization increases men’s vulnerability to noxious media that promotes using violence toward women and other adverse behavior. These findings highlight the interrelation of family and societal/community-based influences on male IPV perpetration and stress that men experience and are particularly significant in that they convey the perspectives of a population that is often missing from research around this stigmatized behavior.

This study identifies and ranks factors within a community that contribute to IPV perpetration and prevention as well as factors that exacerbate stress among men. “No hope for the future” as a clustered construct (cluster 7) was most influential on IPV perpetration and an outcome of underlying socio-structural experiences. Major stress, #55 and seeing domestic violence during childhood, #56 were the highest ranked individual risk factors for IPV perpetration. Community and family experiences were closely related in the men’s expression of IPV perpetration risk factors. Per participants’ interpretation of the cluster map, parental neglect, namely, feeling unloved as a child and exposure to adverse behavior by parents (e.g., drugs, IPV) result in unhealthy intimate partnerships and greater susceptibility to negative community influence (e.g., peers, media). In turn, these factors result in overarching hopelessness or disempowerment. These findings are consistent with research that associate maladaptive behavior among youth who experience neglect [57] and neighborhood violence [40] with IPV perpetration and also provide greater insight into the establishment of gendered social norms among adolescents and young adults through peer influence and media (e.g., reality TV, social media). When these gendered norms (or “masculinities” for men) include using VAW and the acceptability of violence in general, they enable violence against female partners [25, 58]. Childhood neglect increases likelihood of IPV perpetration among men while promoting love seeking behavior in women and may be a point of discussion for individual and/or couple-based interventions [57, 59]. In a similar concept mapping study conducted among women in Baltimore, financial strain/poverty, community violence, substance use, poor mental health, and social tolerance of violence against women were identified as key risk factors for male IPV perpetration [52]. While these factors were also indicated as having influence on male IPV perpetration in the current study, community risk factors for IPV perpetration were presented with greater depth and granularity from the perspectives of men themselves.

Contextual influences on stress were revealed through the second rating prompt. Cluster 5 (struggle—failure with the system), closely followed by cluster 4 (life in Baltimore) and cluster 7 (no hope for the future), contributed the most to stress that men experience. These findings highlighting socio-structural risk factors for VAW (e.g., mass incarceration, street violence, social disorganization) and are consistent with previous research [32, 34, 37, 60, 61].

Men in this study associated their community experiences with physical and verbal IPV and their inability to express love and manage conflicts within intimate relationships. Notably, sexual/reproductive forms of IPV such as reproductive coercion were not included in the men’s narratives, despite evidence that these forms of abuse are prevalent, and disproportionately experienced by women of color [62, 63]. Perhaps drivers of physical and verbal IPV are different from those that influence sexual/reproductive IPV perpetration—this is a point for future research. Furthermore, men may be less cognizant of sexual/reproductive forms of IPV, which have been mostly characterized from the perspective of women [64–66]. Finally, additional research should focus specifically on mechanisms for sexual/reproductive IPV perpetration with emphasis on how men perceive sexual/reproductive behavior.

While the majority of data provided by the participants focused on factors that influenced IPV perpetration, cluster 1 (what reality should be: expectation of support) and cluster 2 (positive environment) shed light on protective factors and thus can inform community-based violence prevention. This study has implications on the development of comprehensive intervention and community-based programming for men to address the root causes of behavior.

Limitations

Study findings should be interpreted with consideration of limitations. Socio-structural influences like mistrust in research posed barriers to recruit a predominantly Black sample of men and influenced subsequent participant participation [67], possibly resulting in selection bias. Some participants lacked reading proficiency. Adaptations for low literacy were established, including assistance from a research team member. While this adaptation facilitated participation, it could have introduced social desirability bias. Additionally, a scarcity of participant resources, including consistent phone communication and transportation, hindered some participant’s ability to attend data collection sessions, contributing to potential selection bias and attrition. We adapted our research plan to include data collection immediately after or before AIP sessions to minimize the need for transportation and used in-person follow-up when needed. Furthermore, the study sample reflects persistent socio-structural disparities as men court-ordered to the sampled AIP were primarily low-income Black men from inner-city Baltimore, which resulted in a relatively homogenous sample. Identified community-based risk factors related to male IPV perpetration in this study may not be generalizable to urban men outside of Baltimore, MD. Our sample size of 28 does fall within the recommended range of 10–40 participants for establishing a suitable framework via concept mapping methodology [68]. Finally, while the sample did not allow for assessment of disparities by race, income, and education, for example, a strength of the study is the richness of data that underscores key risk and protective factors of IPV perpetration among this sample of men. Future studies are needed to examine community influence on IPV perpetration over heterogeneity of demographic factors such as income, education, and environment.

Conclusion

We successfully engaged male IPV perpetrators through concept mapping, an established participatory method used to contextualize complex social problems and discuss potential means for prevention [49]. Place or community spaces where individuals live, work, and play have been the focus of disparities research and implicated as a major source of behavioral and health-adverse risk factors regardless of race [69, 70]. Exposure to prevalent neighborhood violence, witnessing IPV during childhood, and other established risk factors for IPV perpetration should be considered in the development of IPV policy and practice. The current research provides greater insight of family and societal/community-based risk factors for male IPV perpetration, the interrelationship of these two constructs, and the context in which occur. These findings highlight the necessity in shifting from behavior-centric approaches to address the use of violence to an emphasis on social determinants of violence perpetration [71]. The overarching influence of disempowerment brought on by entrenched socio-structural experiences is evident in our findings and represents a clear target for intervention via community-based projects.

The relevance of this research is supported by the limited knowledge of community-level determinants for IPV perpetration from the perspective of men and is also hinged on the adverse health outcomes associated with IPV, including unintended pregnancy and STIs/HIV. These findings have implications for improving women’s health and holistic violence prevention efforts by understanding abusive men’s own perceptions and rankings on specific factors that contribute to IPV perpetration. Evidence, albeit primarily among low- and middle-income countries, shows promise in transforming gender inequitable norms through group training and social communication programs [72, 73]. Policy and programs should consider alternative means that target young men for primary prevention by addressing community factors that contribute to IPV and feelings of disempowerment. Furthermore, future studies should examine the influence of community on reproductive/sexual abuse and risk factors associated with IPV perpetration more broadly among a diverse sample of men. These study findings are the starting point to conversations on how to best address community-based risk factors for IPV perpetration in urban environments, increase self-efficacy, particularly among younger men, and enact trauma-informed violence prevention policy from the perspectives of male IPV perpetrators.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Gateway Project and administrative staff at House of Ruth Maryland, Baltimore, MD, for their partnership and invaluable support with this study. John Miller, Guy Matthews, and Anne Marie Brokmeier provided invaluable research assistance. We also thank Drs. Patricia O’Campo and Alisa Velonis for their research guidance.

This study was supported with funding from the Urban Health Institute at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Holliday), Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (T76MC00003), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32HD06442), and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (1L60MD012089-01—Holliday).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved all data collection procedures.

References

- 1.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Decker MR, Seage GR, Hemenway D, Gupta J, Raj A, Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence perpetration, standard and gendered STI/HIV risk behaviour, and STI/HIV diagnosis among a clinic-based sample of men. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(7):555–560. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black MC, Basile KC, Smith SG, et al. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey 2010 summary report. Natl Cent Inj Prev Control Centers Dis Control Prev. 2010:1–124.

- 6.Coker AL. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frye V, Ompad D, Chan C, Koblin B, Galea S, Vlahov D. Intimate partner violence perpetration and condom use-related factors: associations with heterosexual men’s consistent condom use. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9659-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller E, Jordan B, Levenson R, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion: connecting the dots between partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(6):457–459. 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C. World report on violence and health. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence: variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(9):998–1013. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed E, Lawrence DA, Santana MC, Welles CSL, Horsburgh CR, Silverman JG, Rich JA, Raj A. Adolescent experiences of violence and relation to violence perpetration beyond young adulthood among an urban sample of Black and African American males. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):96–106. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casey EA, Masters NT, Beadnell B, Hoppe MJ, Morrison DM, Wells EA. Predicting sexual assault perpetration among heterosexually active young men. Violence Against Women. 2017;23(1):3–27. doi: 10.1177/1077801216634467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women: intimate partner violence. World Health Organization,; 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2018.

- 14.Mittal M, Te Senn TE, MPM C. Fear of violent consequences and condom use among women attending an STD clinic. Women Health. 2013;53(8):1–11. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2013.847890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed E, Silverman JG, Raj A, Decker MR, Miller E. Male perpetration of teen dating violence: associations with neighborhood violence involvement, gender attitudes, and perceived peer and neighborhood norms. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):226–239. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamndaya M, Pisa PT, Chersich MF, Decker MR, Olumide A, Acharya R, Cheng Y, Brahmbhatt H, Delany-Moretlwe S. Intersections between polyvictimisation and mental health among adolescents in five urban disadvantaged settings: the role of gender. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(S3):41–50. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4348-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heise LL. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Woman. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milam AJ, Buggs SA, Furr-Holden CDM, Leaf PJ, Bradshaw CP, Webster D. Changes in attitudes toward guns and shootings following implementation of the Baltimore safe streets intervention. J Urban Health. 2016;93(4):609–626. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez MB. Policing, community fragmentation, and public health: observations from Baltimore. 2016;93:154–67. 10.1007/s11524-015-0022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Frye V, O’Campo P. Neighborhood effects and intimate partner and sexual violence: latest results. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):187–190. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human-development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513–531. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed E, Silverman JG, Welles SL, Santana MC, Missmer SA, Raj A. Associations between perceptions and involvement in neighborhood violence and intimate partner violence perpetration among urban, African American men. J Community Health. 2009;34(4):328–335. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raj A, Reed E, Santana MC, Welles SL, Horsburgh CR, Flores SA, Silverman JG. History of incarceration and gang involvement are associated with recent sexually transmitted disease/HIV diagnosis in African American men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(1):131–134. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815a5731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming PJ, McCleary-Sills J, Morton M, Levtov R, Heilman B, Barker G. Risk factors for men’s lifetime perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners: results from the international men and gender equality survey (IMAGES) in eight countries. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabriel NC, Sloand E, Gary F, Hassan M, Bertrand DR, Campbell J. “The women, they maltreat them… therefore, we cannot assure that the future society will be good”: male perspectives on gender-based violence: a focus group study with young men in Haiti. Health Care Women Int. 2016;37(7):773–789. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2015.1089875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frye V, Blaney S, Cerdá M, Vlahov D, Galea S, Ompad DC. Neighborhood characteristics and sexual intimate partner violence against women among low-income, drug-involved New York City residents. Violence Against Women. 2014;20(7):799–824. doi: 10.1177/1077801214543501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks Holliday S, Dubowitz T, Haas A, Ghosh-Dastidar B, DeSantis A, Troxel WM. The association between discrimination and PTSD in African Americans: exploring the role of gender. Ethn Health. 2018;0(0):1–15. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1444150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed E, Silverman JG, Ickovics JR, Gupta J, Welles SL, Santana MC, Raj A. Experiences of racial discrimination & relation to violence perpetration and gang involvement among a sample of urban African American men. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(3):319–326. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephenson R, Finneran C. Minority stress and intimate partner violence among gay and bisexual men in Atlanta. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(4):952–961. doi: 10.1177/1557988316677506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coman E, Wu HZ. Examining differential resilience mechanisms by comparing ‘tipping points’ of the effects of neighborhood conditions on anxiety by race/ethnicity. Healthcare. 2018;6(1):18. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peitzmeier SM, Kågesten A, Acharya R, Cheng Y, Delany-Moretlwe S, Olumide A, Blum RW, Sonenstein F, Decker MR. Intimate partner violence perpetration among adolescent males in disadvantaged neighborhoods globally. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Archibald PC, Parker L, Thorpe R. Criminal justice contact, stressors, and obesity-related health problems among black adults in the USA. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2017;5:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gase LN, Glenn BA, Gomes LM, Kuo T, Inkelas M, Ponce NA. Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in arrest: the role of individual, home, school, and community characteristics. Race. 2017;21(2):129–139. doi: 10.1007/s12552-016-9183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonomi AE, Trabert B, Anderson ML, Kernic MA, Holt VL. Intimate partner violence and neighborhood income: a longitudinal analysis. Violence Against Women. 2014;20(1):42–58. doi: 10.1177/1077801213520580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel V, Burns JK, Dhingra M, Tarver L, Kohrt BA, Lund C. Income inequality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. 2018;17:76–89. 10.1002/wps.20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.O’Campo P, Gielen AC, Faden RR, Xue X, Kass N, Wang MC. Violence by male partners against women during the childbearing year: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(8):1092–1097. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson ML, Fox GL. Concentrated disadvantage, economic distress, and violence against women in intimate relationships. J Quant Criminol. 2003;19(3):207–235. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwab-Reese LM, Peek-Asa C, Parker E. Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Inj Epidemiol. 2016;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s40621-016-0069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raiford JL, Seth P, Braxton ND, DiClemente RJ. Interpersonal- and community-level predictors of intimate partner violence perpetration among African American men. J Urban Health. 2013;90(4):784–795. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9717-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casey EA, Leek C, Tolman RM, Allen CT, Carlson JM. Getting men in the room: perceptions of effective strategies to initiate men’s involvement in gender-based violence prevention in a global sample. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19:1–17. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1281438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babcock JC, Steiner R. The relationship between treatment, incarceration, and recidivism of battering: a program evaluation of Seattle’s coordinated community response to domestic violence. J Fam Psychol. 1999;13(1):46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mach JL, Cantos AL, Weber EN, Kosson DS. The impact of perpetrator characteristics on the completion of a partner abuse intervention program. J Interpers Violence. 2017:088626051771990. 10.1177/0886260517719904. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Farzan-Kashani J, Murphy CM. Anger problems predict long-term criminal recidivism in partner violent men. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32(23):3541–3555. doi: 10.1177/0886260515600164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lila M, Gracia E, Catalá-Miñana A. More likely to dropout, but what if they do not? Partner violence offenders with alcohol abuse problems completing batterer intervention programs. J Interpers Violence. 2017;1:088626051769995. doi: 10.1177/0886260517699952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department.; 2016. https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/883366/download. Accessed 24 July 2018.

- 47.Richardson JB, St. Vil C, Sharpe T, Wagner M, Cooper C. Risk factors for recurrent violent injury among black men. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Decker MR, Peitzmeier S, Olumide A, Acharya R, Ojengbede O, Covarrubias L, Gao E, Cheng Y, Delany-Moretlwe S, Brahmbhatt H. Prevalence and health impact of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence among female adolescents aged 15-19 years in vulnerable urban environments: a multi-country study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):S58–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burke JG, Steven AM, editors. Methods for community public health research: integrated and engaged approaches. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burke JG, Campo PO, Peak GL, Gielen AC, Mcdonnell KA, Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. 2005;15(10):1392–1410. doi:10.1177/1049732305278876 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Burke JG, Campo PO, Peak GL. Neighborhood influences and intimate partner violence: does geographic setting matter? 2006;83(2):182–194. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9031-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Campo PO, Burke J, Peak GL, Mcdonnell KA, Gielen AC. Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:603–608. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.027227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campo PO, Salmon C, Burke J. Neighbourhoods and mental well-being: what are the pathways? 2009;15:56–68. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Kane M, Trochim WMK. In: Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Bickman L, Rog DJ, editors. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson JM, Trochim WMK. An examination of community members ’, researchers ’ and health professionals ’ perceptions of barriers to minority participation in medical research: an application of concept mapping an examination of community members ’, Researchers ’ and Health Profe 2007;7858(May 2016). 10.1080/13557850701616987 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Concept Systems I. The Concept System Global MAX. 2016.

- 57.Davis KC, Masters NT, Casey E, Kajumulo KF, Norris J, George WH. How childhood maltreatment profiles of male victims predict adult perpetration and psychosocial functioning. J Interpers Violence. 2015;33:915–937. doi: 10.1177/0886260515613345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Connell R. Masculinities. 2. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McLellan-Lemal E, Toledo L, O’Daniels C, et al. “A man’s gonna do what a man wants to do”: African American and Hispanic women’s perceptions about heterosexual relationships: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frye V, Shanon B, Magdalena C, Vlahov D, Galea S, Ompad DC. Neighborhood characteristics and sexual intimate partner violence against women among low-income, drug-involved New York City residents: results from the impact studies. Violence Against Women. 2015;20(7):799–824. doi: 10.1177/1077801214543501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giurgescu C, Zenk SN, Dancy BL, Park CG, Dieber W, Block R. Relationships among neighborhood environment, racial discrimination, psychological distress, and preterm birth in African American women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(6):E51–E61. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holliday CN, McCauley HL, Silverman JG, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in women’s experiences of reproductive coercion, intimate partner violence, and unintended pregnancy. J Womens Health. 2017;26(8):828–835. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fields JC, King KM, Alexander KA, Smith KC, Sherman SG, Knowlton A. Recently released Black men ’ s perceptions of the impact of incarceration on sexual partnering. Cult Health Sex. 2017;1058(August):1–14. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1325009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nikolajski C, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Race and reproductive coercion: a qualitative assessment. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25(3):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller E, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway JE, Silverman JG. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(5):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kane M, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Vol 50.; 2007. 10.4135/9781412983730

- 69.White K, Haas JS, Williams DR. Elucidating the role of place in health care disparities: the example of racial/ethnic residential segregation. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 PART 2):1278–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D. Place, not race: disparities dissipate in Southwest Baltimore when blacks and whites live under similar conditions. Health Aff. 2011;30(10):1880–1887. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xanthos C, Treadwell HM, Holden KB. Social determinants of health among African-American men. J Mens Health. 2010;7(1):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, Watts C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller E, Tancredi DJ, McCauley HL, et al. “Coaching boys into men”: a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(5):431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]