Abstract

In this study, we investigated the possibility of rearing and breeding the razor clam (Sinonovacula constricta) in inland low salinity water or freshwater. Long-term low salinity (LS) rearing was performed for 3 months to determine the effects of LS on the survival rate, growth rate, and the activities of critical enzymes in juvenile S. constricta (JSC). The survival rate in the LS group was only 15.67% at the end of the LS rearing test. In the first month, the survival rate in the LS group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.001). The growth rate (shell length growth rate and weight gain rate) was significantly lower in the LS group than the control group in the first month (P < 0.001 for length and weight). However, the growth rates in the two groups differed little during the second and third months. The oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion rates by JSCs were significantly higher in the LS group than the control group during the first month, but they decreased gradually during the following 2 months. The Na+/K+ ATPase and superoxide dismutase activities were significantly higher in the LS group than the control group during the first month, but they then decreased gradually until there were no significant differences between the groups. However, the aspartate aminotransferase activity was higher in the LS group than the control group during all 3 months. Most of the JSCs died due to LS but the survival of some JSCs suggests the possibility of breeding LS resistant or freshwater S. constricta.

Introduction

The use of inland low salinity water (ILSW) to culture marine fish and shrimps is effective for increasing aquaculture production1–3. The presence of saline soils in more than 100 countries leads to surface water and groundwater with a salinity of more than 1 ppt4. The Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, is considered to be the most successful invertebrate cultured in low salt conditions. Due to the success of L. vannamei aquaculture in Thailand using a low salinity water containing carbonate, then the culture mode of ILSW, Inland saline water and freshwater were practiced throughout the world5. The production of L. vannamei exceeds 70% of the total global shrimp production5. L. vannamei can be farmed in ILSW with low salinity but also in freshwater with a salinity less than 0.5 ppt6,7. L. vannamei is considered to be a strong regulator of osmotic pressure and it can tolerate a wide range of salinities (0.5–45 ppt)8,9. In addition, other shrimp have been tested to determine the possibility of their cultivation in ILSW, such as Penaeus latisulcatus10 and Penaeus monodon11–13.

Many studies have investigated the acute tolerance of low salinity (LS) by shellfish14–16 based on explorations of the range of acute low salt tolerance by shellfish species and the mortality caused by reduced salinity during the breeding process. However, few long-term LS acclimation studies have been reported with the aim of shellfish culture in ILSW and freshwater. Only six kinds of shellfish have been cultivated in inland saline alkaline waters with high salinity levels, i.e., Cyclina sinensis17, Mytilus edulis18, Haliotis laevigata19, Trochus niloticus20, Crassostrea gigas, and Saccostrea glomerata12, However, no marine shellfish have been cultured in ILSW (very LS) or freshwater, except for L. vannamei.

Pre-culture acclimation to the environment is critical for the LS culture of aquaculture animals. At present, ILSW aquaculture and freshwater aquaculture with marine fish and shrimps require gradient acclimation with seedlings21–23. A single gradient can be used for acclimation to reduced salinity or multiple gradients to slowly acclimate to reduced salinity, which has a great impact on the survival rate of seedlings24. Multiple gradients with slow reductions in salinity can facilitate acclimation and lead to higher seedling survival rates. This acclimation method can also allow animals to adapt better to low salt conditions25.

The most important effect of ILSW and freshwater under excessively low salinity is on the osmotic pressure in marine animals26. Clearly, problems will occur due to imbalances in the proportions of ions, but these issues are not discussed further in this study. The effects of low osmotic pressure in the environment are great and they are thought to directly affect the survival, growth, metabolic levels, and immune responses in fish and shrimp27,28. Robust osmoregulators can avoid these effects and better breeding results may be obtained. In addition, acclimation can reduce these effects26.

Sinonovacula constricta is the one of the most important edible bivalve species in China, and it is distributed in the western Pacific Ocean29. S. constricta is a species that tolerates a wide range of temperatures and acute salinity from 1.8–40 ppt16. Many studies have investigated the effects of water quality parameters on the physiology and growth of S. constricta, such as salinity30, metal ions31, inorganic pollutants32, organic pollutants33, pH34 and carbonate alkalinity35. The effects of salinity on survival and metamorphosis by S. constricta larvae have also been investigated16. However, studies of low salinity acclimation and long-term low salinity aquaculture using S. constricta juveniles with the aim of ILSW and freshwater culture have not been reported.

S. constricta exhibits good environmental tolerance and it requires further investigation because the current saline and freshwater fisheries in China lack edible shellfish farming on an economic scale36. Shellfish aquaculture is considered to be an ecologically sustainable activity37–39. In addition, shellfish consume algae in the water to keep the ecological health40,41. Therefore, we investigated the long-term survival and physical activity of juveniles S. constricta (JSC) under long-term LS stress in order to determine the possibility of using S. constricta as a breeding species in ILSW or freshwater in China.

Materials and Methods

The animals in this experiment were treated according to the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals set by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Ocean University (IACUC-SHOU), Shanghai, China. The examination and approval number SHOU-DW-2018-012. The test animals were non-endangered animals and were artificially propagated larvae.

30-days-old healthy JSCs were collected from Donghang Farm, Sanmen City, Zhejiang Province, China. 100 JSCs were used to measure their initial data (average body weight 0.0164 ± 0.0027 g, average shell length 0.6184 ± 0.069 cm). Sea salts (Red Sea, Red Sea Fish Pharm Ltd, Israel) was used to produce the artificial seawater (ASW). Beach mud collected from the East China Sea at Lingang New City, Shanghai City, China. The test beach mud was produced as described previously35. During the test, the water temperature was controlled at 20–22 °C.

Long-term LS stress test

Before test JSCs were acclimated in 10 ppt ASW for 10 days. Two test groups were set up for the long-term stress tests comprising control and LS groups and every group sets three separate tests. Every separate test was performed in a tank (40 × 40 × 65 cm). Each tank contained JSCs (100 randomly selected), test beach mud (10.4 L) and test water (12 L). 8 days gradual acclimation was performed In LS group (Table 1). The final test water conditions of control and LS groups were show in Table 1 (D8). In addition, the measure value of CA in control and LS groups were 1.22 ± 0.08 mmol · L−1 and 0.28 ± 0.02 mmol · L−1, respectively. Daily changing test water and feeding method as described previously35. During the 100-day stress test (sampling was analyzed on day 8, day 39, day 69, and day 100), we counted the surviving JSCs as well as measuring the growth rate, oxygen consumption rate, ammonia excretion rate, and enzyme activities.

Table 1.

Design of the gradual acclimation scheme for the long-term LS stress test.

| Acclimation time (days) | Control | LS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting salinity (ppt) | Setting CA (mmol · L−1) | Setting pH | Setting salinity (ppt) | Setting CA (mmol · L−1) | Setting pH | |

| D1 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D2 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 5 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D3 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 4 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D4 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 3 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D5 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 2 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D6 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D7 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 1 | 0 | 8.2 |

| D8 | 6 | 0 | 8.2 | 0.5 | 0 | 8.2 |

Oxygen consumption rate and ammonia excretion rate

JSCs were placed in a sealed conical flask to measure the oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion42. The oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion rates of 0-day were measured using 60 randomly selected JSCs. For the control, we tested 60 JSCs (three separate tests with 20 JSCs in each group) per month. There were few individuals in the LS group so all of the surviving JSCs were tested. Dissolved oxygen contents was determined using a dissolved oxygen analyzer (WTW Multi 3420 Set G, Xylem Inc., Germany). Ammonia nitrogen was determined using Nessler’s reagent colorimetric method43.

Enzyme activities

The enzyme activities of 0-day were measured in nine randomly selected JSCs. Nine JSCs (three separate tests with three JSCs in each group) when then tested each month in the control and LS groups used. Using normal saline to dilute homogenized tissue samples (After shelled JSC) at a ratio of 1 g:9 ml (tissue weight: normal saline). The diluted samples were then used to determine the activities of Na+/K+ ATPase (NKA), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and superoxide dismutase (SOD). Coomassie Brilliant Blue Total Protein Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) was used to determine the total protein contents in the diluted tissue samples44. Ultra Trace Na+/K+ ATPase Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China), Aspartate Aminotransferase Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) and Superoxide Dismutase Assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) were used to measure the activities of NKA (units (U) as μmol · Pi · mg · protein−1 · h−1), AST (units (U) as μmol · mg · protein−1 · min−1) and SOD, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The units (U) of SOD as the enzyme content of 50% SOD inhibition in the reaction system.

Calculation and data Analytical methods

Per month survival rate (PMSR)

N(e − 1) and Ne are the numbers of surviving individuals in the (e − 1)-th and e-th month, respectively.

Weight gain rate (WG)

W(e − 1) and We are the wet body weights of the individuals in the (e − 1)-th and e-th month, respectively. T is a months (30 days).

Shell length growth rate (SGR)

L(e − 1) and Le are the lengths of the individuals in the (e − 1)-th and e-th month, respectively. T is a months (30 days).

Oxygen consumption rate

Ammonia excretory rate

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 statistical software was used to perform statistical analyses. Significant differences among treatments were determined using one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s test. Sigmaplot 12.3 software was used to plot figures.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Results

JSC survival under long-term LS stress

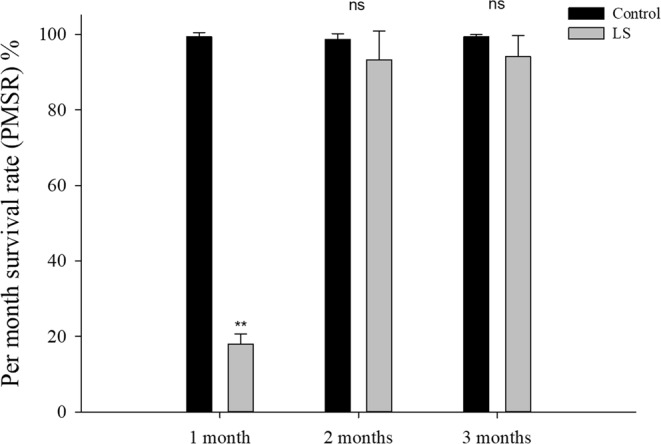

The numbers of JSC deaths each month during long-term LS stress are shown in Table 2. The survival rate of JSCs after 100 days was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in the control group (97.33 ± 1.528%) than the LS group (15.67 ± 1.528%). Figure 1 shows that PMSR differed in the two groups after first month, where PMSR was significantly lower in the LS group than the control group (P < 0.001). In second and third month, high survival rates were maintained in the control group and LS group and there were no significant differences between them.

Table 2.

Growth and death of JSC in the two groups in the long-term LS stress test.

| Measurement items | Groups | Culture time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 2 month | 3 month | ||

| Shell length (cm) | Control | 0.968 ± 0.141 | 1.098 ± 0.075 | 1.268 ± 0.120 |

| LS | 0.723 ± 0.012** | 0.842 ± 0.017** | 1.109 ± 0.024* | |

| Body weight (g) | Control | 0.062 ± 0.004 | 0.102 ± 0.009 | 0.158 ± 0.005 |

| LS | 0.024 ± 0.001** | 0.046 ± 0.002** | 0.102 ± 0.005** | |

| The number of deaths | Control | 0.667 ± 1.155 | 1.333 ± 1.528 | 0.667 ± 0.577 |

| LS | 82.000 ± 2.646** | 1.333 ± 1.528 ns | 1.000 ± 1.000 ns | |

Values (expressed as mean ± SE) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 ns: no significant difference) between the two groups for the same index in each month.

Figure 1.

JSC survival rates per month in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

JSC growth under long-term LS stress

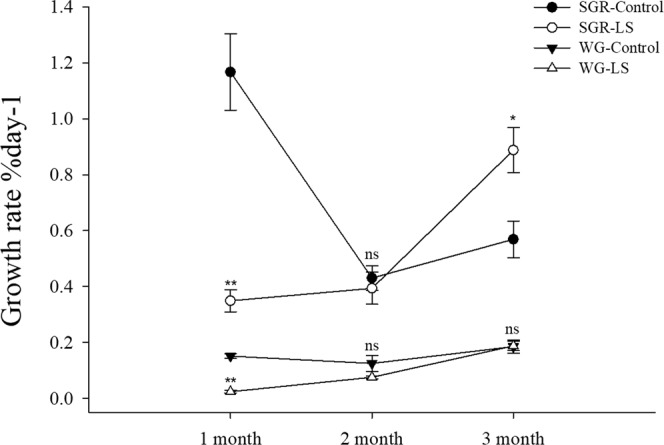

Direct measurements obtained for the shell length and body weight during the three months are shown in Table 2. The JSCs continued to grow during each month in both groups. The shell length and body weight were significantly lower in the LS group than the control group (P < 0.05) throughout the 100-day test period. Figure 2 show that SGR and WG were significantly lower in the LS group than the control group (P < 0.001) during the first month. The SGR was no significant differences in the second month, and it was significant higher in the LS groups than the control group (P < 0.05) in the third month. The WG was significant lower in the LS groups than the control group (P < 0.05) in the second month, and it was no significant differences in the third month.

Figure 2.

JSC growth rate in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

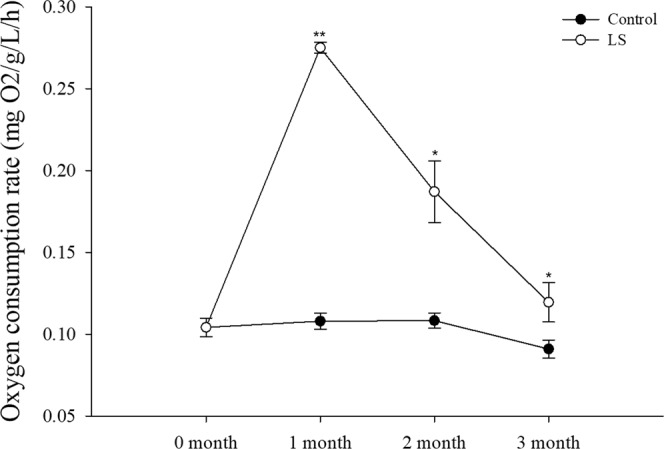

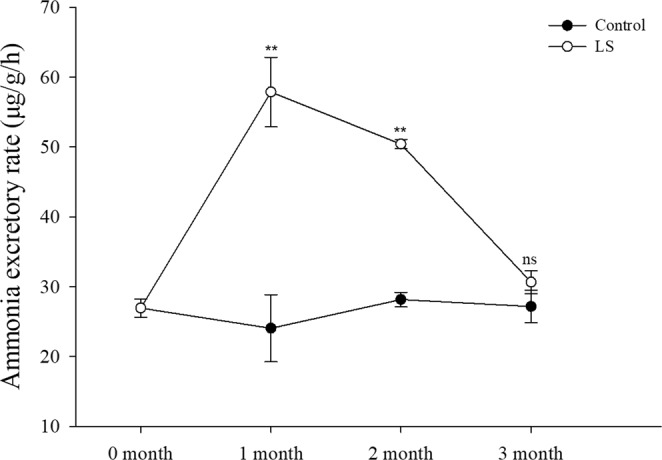

Oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion by JSCs under long-term LS stress

Figure 3 show that the oxygen consumption rate was significantly higher in the LS group than the control group during each month. The results in Fig. 4 are similar to those in Fig. 3 but in the third month show that the ammonia excretion rates in the LS group did not differ significantly from those in the control group.

Figure 3.

JSC oxygen consumption rate in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

Figure 4.

JSC ammonia excretion rate in the long-term LS stress test. For the convenience of display the unit of ammonia excretory rate was converted to (μg · g−1 · h−1). Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

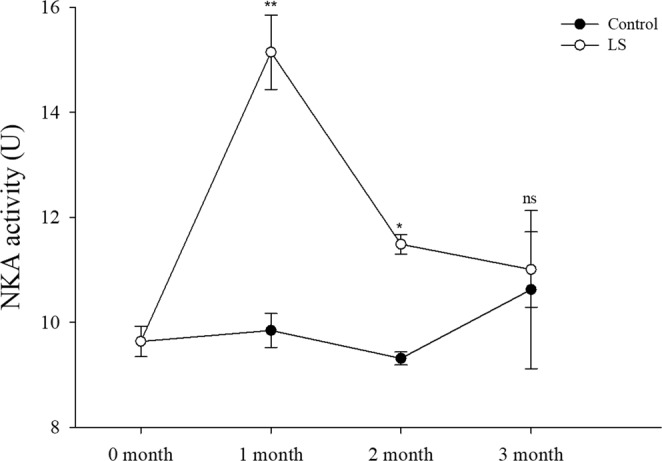

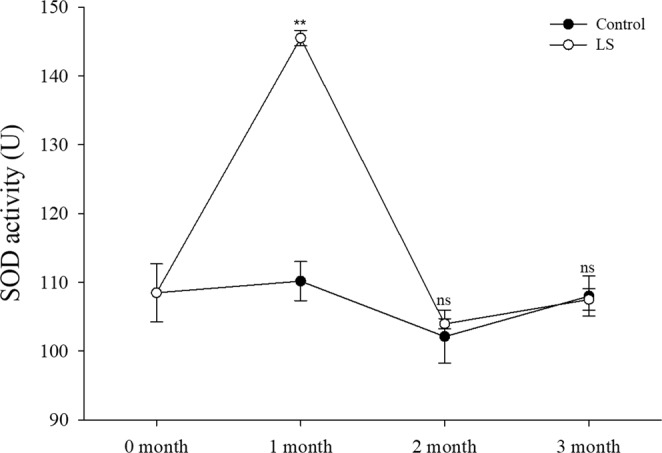

Enzyme activities under long-term LS stress

The NKA activity (Fig. 5) and SOD activity (Fig. 6) were significantly higher in the LS group than the control group during the first month (P < 0.001 for NKA activity, P < 0.001 for SOD activity), but they did not differ significantly in the third months. In the second month NKA activity was significantly higher in the LS group than the control group, but SOD activity did not differ significantly from those in the control group.

Figure 5.

JSC NKA activity levels in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

Figure 6.

JSC SOD activity levels in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

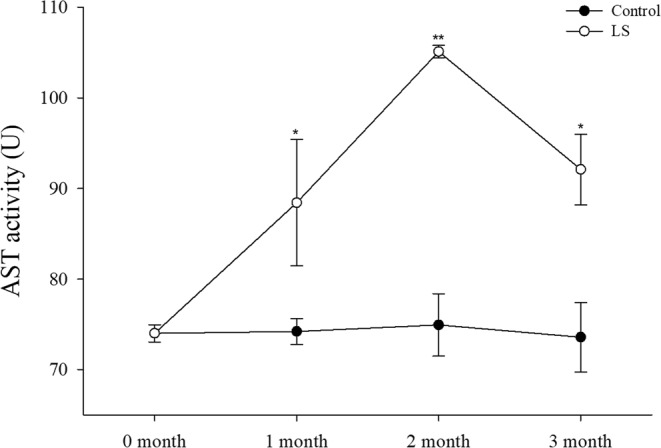

Figure 7 shows that the AST activity was significantly higher in the LS group than the control group during each month (month 1, P < 0.05; month 2, P < 0.001; month 3, P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

JSC AST activity levels in the long-term LS stress test. Bars (mean ± SE, n = 3) with an asterisk denote a significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ns: no significant difference) between the two groups in each month.

Discussion

S. constricta as an estuarine intertidal zone bivalve and it naturally experiences many water quality changes. We have studied the growth traits of S. constricta for many years in our laboratory. Our findings and previous studies suggested that S. constricta is potentially a shellfish with a strong capacity for adapting to different environments. The possible adaptability of S. constricta can be considered in the following context. In its original living environment, Qi45 found that when the salinity was 26 ppt or less, the survival rate of Scylla paramamosain larvae in the Chinese Hainan population was significantly higher than that of the Chinese North Sea population and the Vietnamese population. This was explained by the parents of the Hainan population living in a LS environment (13–20 ppt). Lin and Wu30 also suggested that S. constricta larvae with parents that live in lower salinity environments can adapt better to LS environments. According to a previous study of L. vannamei, differences in the growth stages have important effects on individual LS tolerance. Jayasankar et al.46 showed that the survival rates increased with the postlarval age in L. vannamei but declined as the salinity decreased. Juveniles could tolerate much lower salinities than postlarval individuals. The salinity requirements are different for S. constricta larvae and adults, where the larvae often require lower salinity. In order to obtain a more general understanding of LS aquaculture with S. constricta, juveniles bred from S. constricta parents that lived in normal salinity conditions (12–25 ppt) were selected for testing in the present study. In addition, low salinity acclimation is required before cultivation because it can enhance the survival of LS cultured animals. Kumlu et al.24 found that the transfer of Penaeus indicus postlarvae directly from 30 ppt salinity to 5 ppt without acclimation resulted in a large number of individual deaths. Jayasankar et al.46 and McGraw et al.25 studied the effects of different acclimation methods on the survival rate in L. vannamei, and found that prolonging the acclimation time was more favorable for reducing the stress due to the environmental osmotic pressure and a higher survival rate was obtained. Based on the results of preliminary experiments and a previous study of L. vannamei25, we selected an acclimation period of 8 days for JSCs at salinity levels from 6 ppt to 0.5 ppt. The results showed that the acclimation scheme in Table 1 achieved a high survival rate and greater vigor during acclimation.

According to the survival rate results (Table 2 and Fig. 1), LS had the greatest inhibitory effect on the survival of JSCs at the end of the first month, before the mortality rate stabilized and few deaths occurred subsequently in the control and LS groups. The same trend was reflected by the shell length growth and weight gain (Fig. 2) results. At the end of the second month, the SGR and WG values were show different between the LS group and the control group, thereby suggesting that the adaptation of JSCs to LS may require a longer time and that JSCs may differ in energy dominance under low-salt stress. Laramore et al.47 found that at the end of one month, growth by L. vannamei was significantly lower at 2 ppt salinity than that at 30 ppt salinity. JSCs could adapt well to LS environments in long-term culture but there were individual differences in adaptability. Thus, more than 80% of the JSCs died by the end of the first month and the final survival rate was only 15.67% at the end of the third month. Jayasankar et al.46 found that the survival rate of L. vannamei in water with 1.5 ppt salinity was only 45% after 12 weeks of culture. Therefore, individual differences may exist, thereby indicating that the possibility of selective LS breeding with S. constricta to obtain LS-tolerant S. constricta varieties. To survive in a LS environment, the JSCs needed to consume more energy in order to maintain their physiological needs, which affected energy accumulation, thereby leading to slower growth and even death48,49. Figures 3 and 4 show that the oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion rates increased significantly in the JSCs under LS culture, but they decreased gradually over time. Thus, the higher metabolism of the JSCs in the LS group may have led to a growth lag and high mortality. Fan et al.42 reported that the assimilation rate in S. constricta adults treated acutely with 6 ppt salinity was significantly lower than that under 22 ppt salinity. Emerson50 and Haberfeil et al.51 also showed that the metabolism increased in aquatic invertebrates as the salinity decreased. Pressley et al.52 noted that living in a LS environment can cause the loss of sodium ions. In order to compensate for this loss, it is necessary to activate sodium ion absorption processes. Thus, the increased oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion rate may have been related to the absorption of sodium ions.

Clearly, the physiological changes were related, where LS first caused changes in the osmotic pressure. The body permeability decreases when broad salt marine crustaceans are exposed to a LS environment, where water excretion increases and organic osmolytes in the body fluids are regulated to decrease the osmotic pressure difference between the environment and the hemolymph26. Osmotic pressure regulation is a complex physiological process, but sodium and potassium regulation are mainly mediated by NKA on the gill cells5. The NKA activity was significantly higher in the LS group than the control group in the first month according to Fig. 5, and similar results have been reported previously53–56. The NKA activity was obviously affected by osmoregulation and this consumed large amounts of energy in the JSCs. Huai et al.57 and Jin et al.58 consider that changes in the AST levels are consistent with the growth rate in L. vannamei. However, in the present study, we found that the AST activity increased significantly only in the first month in the LS group (Fig. 7), which may have been related to the role of AST in response to assimilation59. In order to response with changes in salinity in the environment, aquatic organisms passively lose water or absorb water, causing changes in osmotic pressure, NKA enzymes are activated which promote changes in the body’s metabolism until the osmotic pressure tends to stabilize60,61. Thus, the increased NKA activity (osmotic pressure changes) may have increased the oxygen consumption rate, ammonia excretion rate, and AST activity in the first month. The effect of osmotic pressure was crucial and it led to decreased survival and growth. The regulation of salinity changes in crustaceans such as Callinectes danae62, Portunus trituberculatus63 and L. vannamei64 mainly includes passive stress period, active regulation period and adaptation period. In the test of low salt stress (15 ppt) of Anadara broughtonii juvenile shellfish, NKA enzyme activity gradually stabilized after undergoing peak change, and NKA enzyme activity in low-salt group was higher than that of control at stress to 168 h61. In the study of C. sinensis (seawater shellfish), the NKA activity was significantly increased after an acute decrease in salinity (23 ppt → 16 ppt), and reached a peak on the 18th day and then fell back slightly to the initial level65. It suggest that the NKA activity decreased in the second and third months when the effect of osmotic pressure decreased, and thus growth began to accelerate with greater oxygen consumption, and the ammonia excretion rate and AST activity were maintained at relatively high levels. Li et al.2 found that exposing L. vannamei to LS water for a short time significantly increased the SOD activity level. However, Lin et al.66 found no differences in the SOD activity levels in a 2.5 ppt group and 5 ppt group at the end of culture for 24 weeks with L. vannamei. Dong et al. found that the activity of SOD in the Apostichopus japonicus at 16 ppt increased first and then decreased, which was thought to be related to the excessive oxygen stress generated by the metabolism under low salt stress67. It means that SOD may be needed to scavenge the free radicals produced by metabolism during the maintenance of aquatic animal health68.

Conclusions

A decrease in the environmental osmotic pressure can lead to the loss of sodium ions from the body and an increase in the NKA activity. This increase in NKA activity leads to increased metabolic consumption and ammonia excretion, with increased oxygen consumption, AST activity levels, and metabolic free radicals, thereby leading to higher SOD activity levels. The several JSCs that could tolerate the combined effects of these physiological process and have survived, but the energy required led to reduced growth rates. However, some of the JSCs could adapt to these effects under long-term stress and these individuals diverted more energy to growth. Therefore, S. constricta has potential as a species for breeding in ILSW or freshwater in China.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31472278), the “863” Hi-tech Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2012AA10A400-3), and the Shanghai Universities Knowledge Service Platform (grant number ZF1206).

Author Contributions

P.M. was responsible for experimental design, test operations, data processing, and article writing. L.X. was responsible for experimental design, data processing and article modification. Y.B. was responsible for test operations. L.T. was responsible for experimental data collection. L.J., N.D. and D.Z. were responsible for the experimental program guidance.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Peng Maoxiao and Liu Xiaojun contributed equally.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Harikrishna V, Reddy AK, Chadha NK, Babitha AM. Salinity tolerance of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus in inland saline water: effect on growth, survival and haematological parameters. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2017;23:475–482. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li E, et al. Physiological change and nutritional requirement of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei at low salinity. Rev. Aquacult. 2017;9:57–75. doi: 10.1111/raq.12104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mourad N, Kreydiyyeh S, Ghanawi J, Saou I. Aquaculture of marine fish in inland low salinity well water: potassium is not the only limiting element. Fish. Aquac. J. 2012;2012:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keren, R. Handbook of Soil Science (ed. Summer, M. E.) G1–G26 (Boca Raton, 2000).

- 5.Roy LA, et al. Shrimp culture in inland low salinity waters. Rev. Aquacult. 2010;2:191–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-5131.2010.01036.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuvin-Aralar MLA, Lazartigue AG, Aralar EV. Cage culture of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone, 1931) at different stocking densities in a shallow eutrophic lake. Aquac. Res. 2009;40:181–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2008.02081.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcelo A, Eduardo PP, Eucario G-L. White shrimp Penaeus vannamei culture in freshwater at three densities: Condition state based on length and weight. Aquaculture. 2008;283:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray WA, Lawrence AL, Leung-Trujillo JR. The effect of salinity on growth and survival of Penaeus vannamei, with observations on the interaction of IHHN virus and salinity. Aquaculture. 1994;122:133–146. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(94)90505-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menz A, Blake BF. Experiments on the growth of Penaeus vannamei Boone. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 1980;48:99–111. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(80)90010-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prangnell D, Fotedar R. The effect of potassium concentration in inland saline water on the growth and survival of the western king shrimp, Penaeus latisulcatus Kishinouye, 1896. J. Appl. Aquacult. 2005;17:19–34. doi: 10.1300/J028v17n02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins A, Russell B. Inland prawn farming trail in Australia. Pond study tests Penaeus monodon performance in low salinity ground water. Global Aquaculture. Advocate. 2003;2:74–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingram BA, Mckinnon LJ, Gooley GJ. Growth and survival of selected aquatic animals in two saline groundwater evaporation basins: an Australian case study. Aquac. Res. 2002;33:425–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2109.2002.00691.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ur-Rahman S, Jain AK, Reddy AK, Kumar G, Raju KD. Ionic manipulation of inland saline groundwater for enhancing survival and growth of Penaeus monodon (Fabricius) Aquac. Res. 2005;36:1149–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao F, Liu Z, Jie L. Study on adaptability of juveniles of Meretrix meretrix Linnaeus to salinity. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2010;29:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao, R. & Qi, Q. Effects of salinity on the growth and survival of larvae and spats of Coelomactra antiquata (Spengler). J. Fujian. Norm. Univ. (Nat Sci Ed). 11, 82–88 (1995).

- 16.Lin B, Wu T. The effects of temperature and salinity on the larvae of Sinonovacula constricta (Lamarck) Acta. Ecol. Sin. 1984;4:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin T, et al. Toxic effects of several saline-alkali factors on Cyclina sinensis. Mar. Fish. 2012;34:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinh HQ, Fotedar R. Early development of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis (Linnaeus, 1758) cultured in potassium-fortified inland saline water. Aquaculture. 2016;452:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doupé R, Lymbery A, Starcevich M. Rethinking the Land: The Development of Inland Saline Aquaculture in Western Australia. Inter. J. Agr. Sust. 2003;1:30–37. doi: 10.3763/ijas.2003.0104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, C. L. Design and operation of a land-based closed recirculating hatchery system for the topshell, Trochus niloticus, using treated bore water. (eds Smith, B. & Barlow, C.) Trochus: Status, Hatchery Practice and Nutrition. 6–7 (Northern Territory University, 1997).

- 21.Chapman FA, et al. Low-salinity acclimation of juvenile marine goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara. J. Appl. Aquacult. 2014;26:179–186. doi: 10.1080/10454438.2014.905356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mcgraw WJ, Davis DA, Teichertcoddington D, Rouse DB. Acclimation of Litopenaeus vannamei postlarvae to low salinity: influence of age, salinity endpoint, and rate of salinity reduction. J. World. Aquac. Soc. 2002;33:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-7345.2002.tb00481.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Li K, Huang Z, Liu W, Song G. Preliminary study on pollution-free Paralichthys olivaceau culture technology. J. Aquac. 2004;25:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumlu M, Jones DA. Salinity tolerance of hatchery-reared postlarvae of Penaeus indicus H. Milne Edwards originating from India. Aquaculture. 1995;130:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(94)00319-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mcgraw WJ, Scarpa J. Mortality of freshwater-acclimated Litopenaeus vannamei associated with acclimation rate, habituation period, and ionic challenge. Aquaculture. 2004;236:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.01.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Péqueux A. Osmotic Regulation in Crustaceans. J. Crustacean. Biol. 1995;15:1–60. doi: 10.2307/1549010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Álvarez AL, Racotta IS, Arjona O, Palacios E. Salinity stress test as a predictor of survival during grow out in pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Aquaculture. 2004;237:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portz DE, Woodley CM., Jr J.J.C. Stress-associated impacts of short-term holding on fishes. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2006;16:125–170. doi: 10.1007/s11160-006-9012-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie S, et al. Molecular characterization of IGFBP and association analysis with growth traits in the razor clam Sinonovacula constricta. J. Fish. China. 2015;39:799–809. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin B, Wu T. Temperature and salinity in relating to the survinal, growth and development of the larvae and spat of Sinonovacula constricta. J. Fish. China. 1990;14:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z, Pan L, Dong S. Effects of nine metal ions on digestive enzyme activities of Sinonovacula constricta. J. Fish. Sci. China. 2003;10:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, et al. Preliminary studies on the use of cyanide in the cultivation of the rajor clam. J. Xiamen. Univ. (Nat Sci) 1984;5:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang M, et al. Investigation of toxic effects of No.0 fuel oil and Pinghu crude oil on Sinonovacula constricta by using integrated biomarker responses. Acta. Scien. Circum. 2015;35:1174–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 34.He M, et al. Effects of pH and temperature on carbon budget of Sinonovacula constricta. Chin J. Ecol. 2017;36:1014–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng M, et al. Effects of alkalinity and ph on survival, growth, and enzyme activities in juveniles of the razor clam, Sinonovacula constricta. Front. Physiol. 2018;9:00552. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi, Y. Studies on water quality characteristics and change regulations of culture ponds with heavy saline-alkaline soil. Shanghai Ocean University (2009).

- 37.Palmer, P. J. & Rutherford, B. W. Bivalves for the remediation of prawn farm effluent: identification of some potentially useful species in Southern Queensland (2005).

- 38.Shumway SE, et al. Shellfish aquaculture - in praise of sustainable economies and environments. Data. 2003;34:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolley SG, Volety AK, Savarese M. Shellfish research and adaptive resource management in Southwest Florida: oysters as sentinels of ecosystem health. World. Aquacult. 2004;1:31–66. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumbauld BR, Ruesink JL, Rumrill SS. The ecological role of bivalve shellfish aquaculture in the estuarine environment: a review with application to oyster and clam culture in West Coast (USA) estuaries. Aquaculture. 2009;290:196–223. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo K, Zhao W, Jiang Z, Dong S. A study of organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus budget in jellyfish–shellfish–fish–prawn polyculture ponds. Aquac. Res. 2017;48:68–76. doi: 10.1111/are.12861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan D, Pan L, Ma S, Dong S. Effects of salinity and pH on oxygen consumption rate and ammonia excretion rate in Sinonovacula constricta. J. Fish. Sci. China. 2002;9:234–238. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson J, Morrison G. Determination of Organic Nitrogen. Control of Variables in the Use of Nessler’s Reagent. Anal. Chem. 1951;23:1153–1157. doi: 10.1021/ac60056a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sedmak JJ, Grossberg SE. A rapid, sensitive, and versatile assay for protein using Coomassie brilliant blue G250. Anal. Biochem. 1977;79:544–552. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi, L. Morphological variations analysis of different populations of Scylla paramamosain in China and their ecological adaptability to low salinity. Shanghai Ocean University Shanghai (2011).

- 46.Jayasankar V, et al. Low salinity rearing of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: acclimation, survival and growth of postlarvae and juveniles. Jarq-Jpn. Agr. Res. 2009;Q4:345–350. doi: 10.6090/jarq.43.345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laramore S, Laramore CR, Scarpa J. Effect of low salinity on growth and survival of postlarvae and juvenile Litopenaeus vannamei. J. World. Aquac. Soc. 2001;32:385–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-7345.2001.tb00464.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johns DM. Physiological studies on Cancer irroratus larvae. I. effects of temperature and salinity on survival, development rate and size. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1981;5:75–83. doi: 10.3354/meps005075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kannupandi T, Krishnan T, Shanmugam A. Effect of salinity on the larvae of an edible estuarine crab Thalamita crenata (Crustacea, Decapoda, Portunidae) Indian J. Mar. Sci. 1997;26:315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emerson DN. Influence of salinity of ammonia excretion rates and tissue constituents of euryhaline invertebrates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1969;29:1115–1133. doi: 10.1016/0010-406X(69)91017-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haberfield EC, Haas LW, Hammen CS. Early ammonia release by a polychaete Nereis virens and a crab Carcinus maenas in diluted sea water. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 1975;52:501–503. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9629(75)80072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pressley TA, Graves JS, Krall AR. Amilioride-sensitive ammonium and sodium ion transport in the blue crab. Am. J. Physiol. 1981;241:R370. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.5.R370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jorgensen PL. Importance for Absorption of Na+ from Freshwater of Lysine, Valine and Serine Substitutions in the α1a-Isoform of Na,K-ATPase in the Gills of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) J. Membr. Biol. 2008;223:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s00232-008-9111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin CH, Lee TH. Sodium or potassium ions activate different kinetics of gill Na, K-ATPase in three seawater- and freshwater-acclimated euryhaline teleosts. J. Exp. Zool. Part. A. 2005;303A:57–65. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saoud IP, Roy LA, Davis DA. Chelated potassium and arginine supplementation in diets of pacific white shrimp reared in low-salinity waters of west Alabama. N. Am. J. Aquacult. 2007;69:265–270. doi: 10.1577/A06-045.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verbost PM, Schoenmakers TJ, Flik G, Wendelaar Bonga SE. Kinetics of ATP- and Na(+)-gradient driven Ca2+ transport in basolateral membranes from gills of freshwater- and seawater-adapted tilapia. J. Exp. Biol. 1994;186:95. doi: 10.1242/jeb.186.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huai M, et al. Quantitative dietary threonine requirement of juvenile Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone) reared in low-salinity water. Aquac. Res. 2009;40:904–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02181.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jin Y, Liu F, Liu Y, Tian L, Zhang Z. Dietary tryptophan requirements of juvenile pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone) reared in low-salinity water. Aquac. Int. 2017;25:955–968. doi: 10.1007/s10499-016-0098-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirsch JF, et al. Mechanism of action of aspartate aminotransferase proposed on the basis of its spatial structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;174:497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He X, Zhuang P, Zhang L, Xie C. Osmoregulation in juvenile Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis Gray) during brackish water adaptation. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 2009;35:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s10695-008-9230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai X, Zhang. X, Tian L, Zhang P. Effect of salinity stress on hemolymph osmolality and gill Na+/K+–ATPase activity of juvenile ark shell (Anadara broughtonii) South China Fisheries Science. 2015;11:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masui DC, Mantelatto FLM, Mcnamara JC, Furriel RPM, Leonea FA. Na+/K+–ATPase activity in gill microsomes from the blue crab, Callinectes danae, acclimated to low salinity: novel perspectives on ammonia excretion. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 2009;153:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang S, Xu Q. Influence of salinity stress on the activity of gill Na+/K+–ATPase in swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus) J. Fish. China. 2011;35:1475–1480. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palacios E, Bonilla A, Luna D, Racotta IS. Survival, Na+/K+–ATPase and lipid responses to salinity challenge in fed and starved white Pacific shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) postlarvae. Aquaculture. 2004;234:497–511. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2003.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin T, et al. Effect of abrupt variations in salinity on the Na+/K+−ATPase activity in gills of Cyclina sinensis. J. Guangdong. Ocean. University. 2012;32:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Y, et al. Modulation of the innate immune system in white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei following long-term low salinity exposure. Fish. Shellfish. Immun. 2012;33:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong X, et al. Effect of low salinity stress on the activities of non-specific immune enzymes and antibacterial activity of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Prog. Fish. Sci. 2013;3:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li E, et al. Comparison of digestive and antioxidant enzymes activities, haemolymph oxyhemocyanin contents and hepatopancreas histology of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, at various salinities. Aquaculture. 2008;274:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]