Abstract

Excitatory synapses can be potentiated by chemical neuromodulators, including 17β-estradiol (E2), or patterns of synaptic activation, as in long-term potentiation (LTP). Here, we investigated kinases and calcium sources required for acute E2-induced synaptic potentiation in the hippocampus of each sex and tested whether sex differences in kinase signaling extend to LTP. We recorded EPSCs from CA1 pyramidal cells in hippocampal slices from adult rats and used specific inhibitors of kinases and calcium sources. This revealed that, although E2 potentiates synapses to the same degree in each sex, cAMP-activated protein kinase (PKA) is required to initiate potentiation only in females. In contrast, mitogen-activated protein kinase, Src tyrosine kinase, and rho-associated kinase are required for initiation in both sexes; similarly, Ca2+/calmodulin-activated kinase II is required for expression/maintenance of E2-induced potentiation in both sexes. Calcium source experiments showed that L-type calcium channels and calcium release from internal stores are both required for E2-induced potentiation in females, whereas in males, either L-type calcium channel activation or calcium release from stores is sufficient to permit potentiation. To investigate the generalizability of a sex difference in the requirement for PKA in synaptic potentiation, we tested how PKA inhibition affects LTP. This showed that, although the magnitude of both high-frequency stimulation-induced and pairing-induced LTP is the same between sexes, PKA is required for LTP in females but not males. These results demonstrate latent sex differences in mechanisms of synaptic potentiation in which distinct molecular signaling converges to common functional endpoints in males and females.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Chemical- and activity-dependent neuromodulation alters synaptic strength in both male and female brains, yet few studies have compared mechanisms of neuromodulation between the sexes. Here, we studied molecular signaling that underlies estrogen-induced and activity-dependent potentiation of excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. We found that, despite similar magnitude increases in synaptic strength in males and females, the roles of cAMP-regulated protein kinase, internal calcium stores, and L-type calcium channels differ between the sexes. Therefore, latent sex differences in which the same outcome is achieved through distinct underlying mechanisms in males and females include kinase and calcium signaling involved in synaptic potentiation, demonstrating that sex is an important factor in identification of molecular targets for therapeutic development based on mechanisms of neuromodulation.

Keywords: calcium, hippocampus, LTP, PKA, synapse

Introduction

There is compelling evidence that the hippocampus can synthesize estrogens as neurosteroids. In vitro studies initially showed that neural synthesis of 17β-estradiol (E2) is possible both in cell culture (Prange-Kiel et al., 2003) and in acute hippocampal slices (Hojo et al., 2004). More recently, studies from our lab (Sato and Woolley, 2016) and others (Tuscher et al., 2016) have shown that hippocampal neurosteroid E2 synthesis also occurs in vivo. These observations motivate efforts to understand the mechanisms by which E2 synthesized in the hippocampus could influence hippocampal neurophysiology.

One likely action of neurosteroid E2 is to acutely modulate synaptic transmission. It has been known for decades that E2 can potentiate excitatory synapses in the hippocampus on a time scale of minutes and in both sexes (Teyler et al., 1980; Wong and Moss, 1992; Kramár et al., 2009; Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010). E2 has also been shown to suppress perisomatic inhibitory synapses on a similar acute time scale, although this occurs only in females (Huang and Woolley, 2012).

The possibility that acute E2-induced excitatory synaptic potentiation shares underlying mechanisms with other forms of synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation (LTP) suggests molecular signaling that could be involved in E2-induced synaptic potentiation. Indeed, multiple kinases known to be important in LTP, including Src tyrosine kinase (Bi et al., 2000), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Zadran et al., 2009), rho-associated kinase (ROCK) (Kramár et al., 2009), and Ca2+/calmodulin-activated kinase II (CaMKII) (Hasegawa et al., 2015), have been indicated in E2-induced synaptic potentiation in one or the other sex. In addition, acute E2 potentiation of kainate-evoked currents in female hippocampal neurons depends on cAMP-activated protein kinase (PKA) (Gu and Moss, 1996), which is implicated in some (Blitzer et al., 1998; Otmakhova et al., 2000; Yasuda et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006) but not other (Huang and Kandel, 1994; Abel et al., 1997; Park et al., 2014) forms of LTP. Despite this extensive literature, however, no study has directly compared the involvement of specific kinases in E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males versus females to investigate the possibility of sex differences.

Therefore, the first aim of the current study was to test the requirement for five kinases known to be involved in LTP: PKA, MAPK, ROCK, Src, and CaMKII, in the initiation and expression/maintenance of E2-induced potentiation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of each sex. The results showed that each kinase is involved either in initiation or expression/maintenance. Further, whereas most of the kinases tested were similarly required in males and females, we found that PKA plays a sex-specific role in initiation, being required only in females. Given this sex difference, we then investigated whether mechanisms that underlie E2-induced synaptic potentiation also involve distinct sources of increased intracellular calcium in males and females, namely L-type calcium channels and calcium release from internal stores. These experiments showed that, whereas both L-type calcium channels and calcium release from stores are required for E2-induced potentiation in females, in males, either of these calcium sources appears to be able to compensate for the other. Finally, to test the generalizability of a sex difference in the involvement of PKA in synaptic plasticity, we tested how PKA inhibition affects LTP in each sex. This showed that multiple forms of LTP require PKA specifically in females and not in males. Therefore, sex differences in molecular signaling that underlies synaptic plasticity extend beyond neurosteroid estrogen actions and may be broadly relevant for the translation of basic mechanisms of neuromodulation to the development of therapeutics appropriate for each sex.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Young adult female and male Sprague Dawley rats (50–70 d of age; Envigo) were group-housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to water and phytoestrogen-free chow. All rats were gonadectomized 3–8 d before being used for experiments. Surgeries were performed under ketamine (85 mg/kg, i.p.; Bioniche Pharma) and xylazine (13 mg/kg, i.p.; Lloyd Laboratories) anesthesia using aseptic surgical procedures. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Preparation of hippocampal slices

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100–125 mg/kg, i.p.; Virbac) and transcardially perfused with oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) ice-cold sucrose-containing artificial CSF (s-aCSF) containing the following (in mm): 75 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 15 dextrose, 75 sucrose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 KCl, 2.4 Na pyruvate, 1.3 L-ascorbic acid, 0.5 CaCl2, and 3 MgCl2, 305–310 mOsm/L, pH 7.4. The brain was quickly removed and 300 μm transverse slices through the dorsal hippocampus were cut into a bath of ice-cold s-aCSF using a vibrating tissue slicer (VT1200S; Leica). The slices were incubated at 33°C in oxygenated regular aCSF containing the following (in mm): 126 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 dextrose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, and 1 MgCl2, 305–310 mOsm/L, pH 7.4, for 30 min, then allowed to recover at room temperature for 1–6 h until recording.

Electrophysiological recording

Slices were transferred to a recording chamber mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop and were perfused with warm (33°C) oxygenated regular aCSF at a rate of ∼2 ml/min. In most experiments, somatic whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings (Vhold = −70 mV) were obtained from visually identified CA1 pyramidal cells using patch electrodes (4–7 MΩ) filled with intracellular solution containing the following (in mm): 115 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 Na creatine phosphate, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, and 0.001 QX-314 chloride salt, 290–295 mOsm/L, pH 7.2. In a subset of experiments, extracellular field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were recorded with a glass pipette filled with regular aCSF (1–2 MΩ) and positioned in the CA1 stratum radiatum ∼150 μm from the cell body layer. A glass bipolar stimulating electrode (10–50 μm tip diameter) filled with regular aCSF was placed in the stratum radiatum 200–250 μm from the recorded cell in whole-cell recordings or 100–200 μm from the recording pipette in fEPSP recordings. During an experiment, stimulation intensity was fixed at 50% of the maximal response and stimuli were delivered every 15 s to evoke EPSCs or fEPSPs. For whole-cell recordings, series resistance (20–45 MΩ) was monitored throughout each recording and experiments were discontinued if series resistance fluctuated by >20%. All E2 experiments were done in the presence of the GABAA and NMDA receptor blockers SR-95531 (2 μm) and DL-APV (25 μm), respectively, and were terminated by applying DNQX (25 μm) to confirm that the recorded EPSCs were mediated by AMPA receptors. LTP experiments were done in the presence of SR-95531 (2 μm). Data were acquired with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier and pClamp 10.5 software (Molecular Devices), filtered at 1–2 kHz, and digitized at 5 kHz or 20 kHz using a Digidata 1440A data acquisition system (Molecular Devices).

To investigate the roles of specific kinases in E2-induced synaptic potentiation, two types of protocols were used. In the first, baseline EPSCs were recorded for 10–20 min, followed by application of a kinase inhibitor 10–20 min before applying E2 (10 min) in the presence of the inhibitor to test the requirement of each kinase in initiation and/or expression of E2-induced potentiation. In the second protocol, kinase inhibitors were applied after E2-induced potentiation was established to determine the requirement of each kinase in the maintenance of potentiation. To investigate the roles of calcium release from internal stores and L-type calcium channels, baseline EPSCs were recorded, followed by application of thapsigargin and/or nifedipine for the remainder of the experiment.

To test the involvement of PKA in LTP, three protocols were used, each with or without the cell-permeant PKA inhibitor myristoylated PKI (mPKI) in the bath. In extracellular recordings, baseline fEPSPs were recorded for 15–20 min until stable. Then, high-frequency stimulation (HFS, 1 s at 100 Hz) was delivered once or three times with a 10 min interval (Huang and Kandel, 1994) and fEPSPs were recorded for 50–55 min after LTP induction. In whole-cell recordings, baseline EPSCs were recorded for 10–12 min and then LTP was induced by pairing postsynaptic depolarization to 0 mV with 200 presynaptic stimulations delivered at 1.4 Hz (Otmakhova et al., 2000). In most cells, EPSCs were recorded for 40–50 min following induction of LTP, except for four cells (one each in female control and mPKI and two male mPKI) in which EPSCs could be recorded for only 30–40 min following LTP induction.

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from Tocris Bioscience unless otherwise specified. Stock solutions of DL-APV, SR-95531, H89, mPKI, KN93, PD98059, SU6656, Y27632, QX-314, and tatCN21 (Calbiochem) were prepared in ddH2O, whereas 17β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich), nifedipine, thapsigargin, and DNQX were made in DMSO. The bath contained an equivalent concentration of DMSO 0.01% (v/v) in all phases of each experiment. Stock solutions were stored at −20°C and diluted in aCSF on the day of recording to achieve final concentrations.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

Clampfit 10.5 was used to analyze EPSCs and fEPSPs. IGOR (version 6.37) and GraphPad Prism (version 6.0) were used to perform statistical analyses. To determine the E2 responsiveness of each recording individually, unpaired, two-tailed t tests were used to compare EPSC amplitude during 2 min immediately before E2 application to 2 min beginning 4 min after E2 was removed from the bath. Measured EPSC amplitudes for each E2-responsive recording are shown in the figures and data are discussed in the text as mean ± SEM percentage change from baseline. Two-tailed Fisher's exact tests were used to compare the proportions of cells that responded to E2 between sexes within an experiment and within-sex between different experiments. Unpaired, two-tailed t tests were used to compare the magnitude of E2-induced potentiation between sexes. To determine whether pharmacological inhibitors affected EPSC amplitude in E2-responsive experiments, unpaired, two-tailed t tests were performed within cell to compare EPSCs recorded during 2 min immediately before application of the inhibitor to EPSCs recorded during 2 min beginning 10 min after the inhibitor was applied. In experiments to test the role of CaMKII on E2-potentiated EPSCs, in addition to within-cell analyses, paired, two-tailed t tests were performed to evaluate the effect of tatCN21 within each sex. Measured EPSC amplitudes for each E2-responsive recording in each condition are shown in the figures and data are discussed in the text as mean ± SEM percentage change between pairs of conditions.

For LTP experiments, the initial slope of fEPSPs or amplitude of EPSCs were measured and the magnitude of potentiation within each recording was determined by comparing fEPSPs or EPSCs recorded during the last 10 min of the baseline period to those recorded from 40–50 min after LTP induction (or during the last 10 min of the four EPSC recordings that lasted <50 min following LTP induction). Paired, two-tailed t tests were used to determine whether each LTP induction protocol produced significant potentiation within each group (male control, male mPKI, female control, female mPKI). Two-way ANOVA was used to test for an interaction between mPKI and sex in the magnitude of LTP, followed by Bonferroni multiple-comparisons post hoc tests to evaluate differences in LTP magnitude between groups. To generate LTP plots, data for each slice or cell were normalized to the average fEPSP slope or EPSC amplitude during the baseline period and mean ± SEM normalized fEPSP slope or EPSC amplitude are shown per minute in the figures. Results are discussed in the text as mean ± SEM percentage increase above baseline in fEPSP slope or EPSC amplitude following LTP induction.

All statistics were calculated with n as the number of cells for whole-cell recordings or number of slices for fEPSP recordings. We recorded one to four cells or slices per animal with four to eight animals per experiment, except for one control tatCN21 experiment in which two cells from two animals were used. Significance for statistical tests was defined as p < 0.05. Full results of all statistically significant comparisons are included in the text.

Results

PKA is required for initiation of acute E2-induced potentiation of excitatory synapses in females but not in males

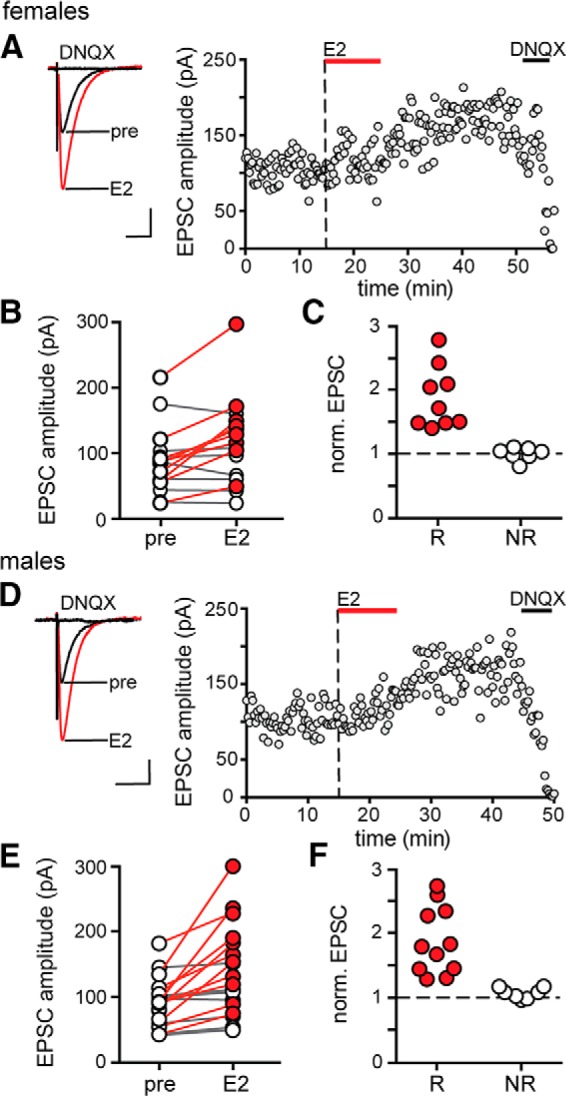

Previously, we found that E2 acutely potentiates EPSCs in a subset of CA1 pyramidal cells of adult female rats (Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010). To determine whether this effect of E2 is similar between the sexes, we performed whole-cell recordings from CA1 neurons and recorded EPSCs evoked by Schaffer collateral stimulation before, during, and after 10 min exposure to E2 (100 nm) in acute hippocampal slices from males and females. This showed that E2 increased EPSC amplitude within minutes in a subset of recordings in both sexes. Within-cell t tests showed that E2 significantly increased EPSC amplitude in 9 of 16 cells from females (Fig. 1A,B) by 83 ± 16% (range: 35–172%; Fig. 1C). Similarly, in males, E2 significantly increased EPSC amplitude in 11 of 18 cells (Fig. 1D,E), by 89 ± 16% (range: 26–175%; Fig. 1F). In both sexes, EPSC amplitude began to increase within 5–8 min of E2 application and remained elevated following E2 washout. Neither the proportion of cells that responded to E2 (Fishers exact test, p > 0.1) nor the magnitude of EPSC potentiation in responsive cells (unpaired t test, p > 0.1) differed between the sexes. Therefore, there is no apparent sex difference in the acute effect of E2 to potentiate evoked EPSCs.

Figure 1.

E2 potentiates excitatory synaptic transmission in both females and males. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in females in which E2 (100 nm) was applied for 10 min. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in D). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for experiments in females (n = 16) showing that E2 potentiated EPSC amplitude in a subset of experiments in females. Points in red represent experiments that showed a significant difference in EPSC amplitude following E2 (n = 9, unpaired t test, p < 0.05) and nonresponsive experiments are in white (n = 7). C, Normalized group EPSC amplitude data for E2 experiments in females where the magnitude of potentiation is shown separately for E2-responsive (R, red) and nonresponsive (NR, white) experiments. D, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in males in which E2 was applied for 10 min. E, Group EPSC amplitude data for experiments in males (n = 18) showing that E2 potentiated EPSC amplitude in a subset of experiments in males. Points in red represent experiments that showed a significant difference in EPSC amplitude following E2 (n = 11, unpaired t test, p < 0.05) and nonresponsive experiments are in white (n = 7). F, Normalized group EPSC amplitude data for E2 experiments in males as in C. Scale bars, 50 pA, 25 ms.

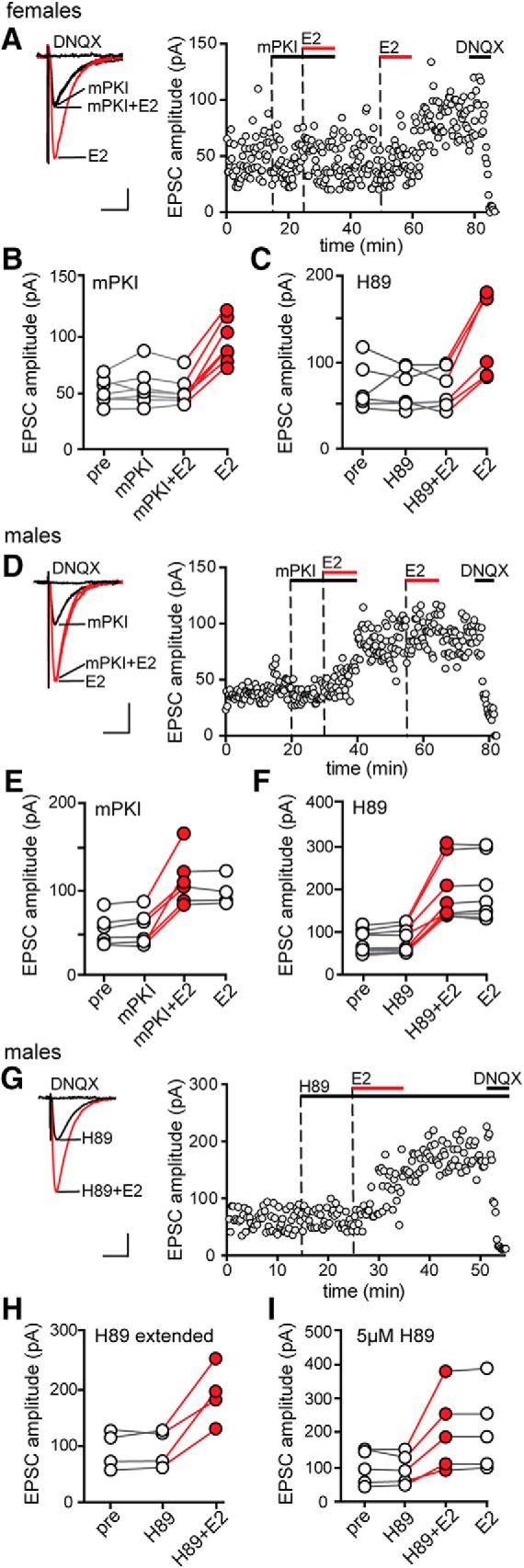

Early studies in dissociated CA1 neurons showed that cAMP/PKA signaling is required for E2-induced potentiation of kainate-evoked currents in females (Gu and Moss, 1996). To test whether PKA is also required for E2 potentiation of synaptic transmission, we inhibited PKA activity by bath application of either membrane-permeant mPKI (0.5 μm) or H89 (1 μm), which have different mechanisms of action. PKA inhibitors were applied after establishing baseline values for EPSC amplitude, E2 was applied for 10 min in the presence of the inhibitor and then, because ∼40% of recordings are not responsive to E2, E2 was applied a second time after inhibitor washout to test for E2 responsiveness of EPSCs. Within-cell t tests were used to evaluate significant differences between each condition. Identical experiments were done in females and males.

In females, inhibiting PKA with mPKI blocked E2-induced EPSC potentiation (Fig. 2A). Applying mPKI itself had no effect on EPSC amplitude (5 ± 5%) and E2 applied in the presence of mPKI failed to increase EPSC amplitude in any of 7 E2-responsive cells (Fig. 2B) in 11 recordings. The magnitude of potentiation induced by E2 following mPKI washout (86 ± 12%, range: 42–129%) was the same as that with E2 alone (unpaired t test, p > 0.1). Identical experiments done with H89 confirmed that inhibiting PKA blocked E2-induced potentiation of EPSCs in females (6 E2-responsive cells in 10 recordings; Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

PKA is required for initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in females but not in males. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in females in which mPKI (0.5 μm) was applied before applying E2 in the presence of mPKI and a second application of E2 confirmed E2 responsiveness. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in D and G). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with mPKI in females (n = 7) showing that mPKI blocked E2-induced synaptic potentiation in females. Points in red represent a significant difference in EPSC amplitude compared with the preceding condition (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in C, E, F, H, and I). C, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with H89 in females (n = 6), which confirmed mPKI results. D, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in males in which mPKI (0.5 μm) was applied before applying E2 in the presence of mPKI. E, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with mPKI in males (n = 6) showing that mPKI failed to block E2-induced potentiation in males. F, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with H89 in males (n = 9), which confirmed mPKI results. G, Individual traces and time course of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in males in which H89 was applied until the end of the recording. H, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done in males with extended application of H89 (n = 4). I, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done in males with a higher concentration of H89 (5 μm, n = 5). Scale bars, 25 pA, 25 ms.

In contrast to the results in females, mPKI failed to block E2 potentiation of EPSCs in males (Fig. 2D). E2 applied in the presence of mPKI increased EPSC amplitude by 115 ± 23% (range: 76–224%; Fig. 2E) in 6 E2-responsive cells from 10 recordings in males. EPSC amplitude remained elevated following mPKI+E2 washout and a second application of E2 had no further effect (Fig. 2E). The magnitude of E2-induced EPSC potentiation in the presence of mPKI was not different from that with E2 alone (unpaired t test, p > 0.1). As in females, mPKI alone had no effect on EPSC amplitude in males (3 ± 4%). Experiments with H89 also showed that inhibiting PKA failed to block E2-induced potentiation of EPSCs in males (9 E2-responsive cells in 13 recordings; Fig. 2F).

We performed two additional experiments to confirm that PKA inhibition does not block EPSC potentiation in males. First, to test whether the apparent E2-induced increase in EPSC amplitude in males was related to washout of the PKA inhibitor, we extended H89 application for the duration of an experiment (Fig. 2G). This showed that E2 increased EPSC amplitude even in the continued presence of H89 (4 E2-responsive cells in 5 recordings; Fig. 2H). Second, we tested a higher concentration of H89 (5 μm) and found that this also failed to block E2 potentiation of EPSCs in males (5 E2-responsive cells in 7 recordings; Fig. 2I). Therefore, the results of experiments with PKA inhibitors showed that PKA activity is required for initiation of E2-induced EPSC potentiation in females, but not in males.

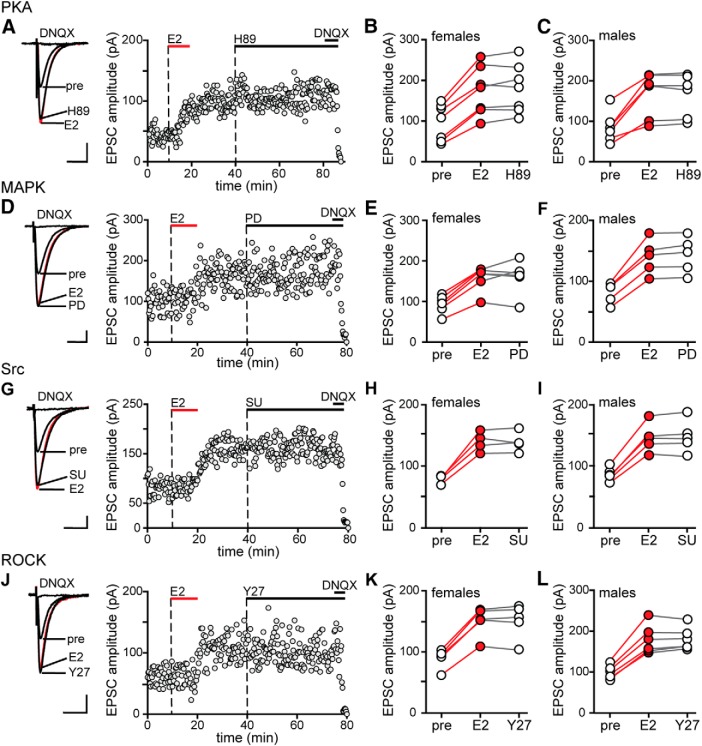

MAPK, Src, and ROCK are each required for initiation of E2-induced potentiation of excitatory synapses in both sexes

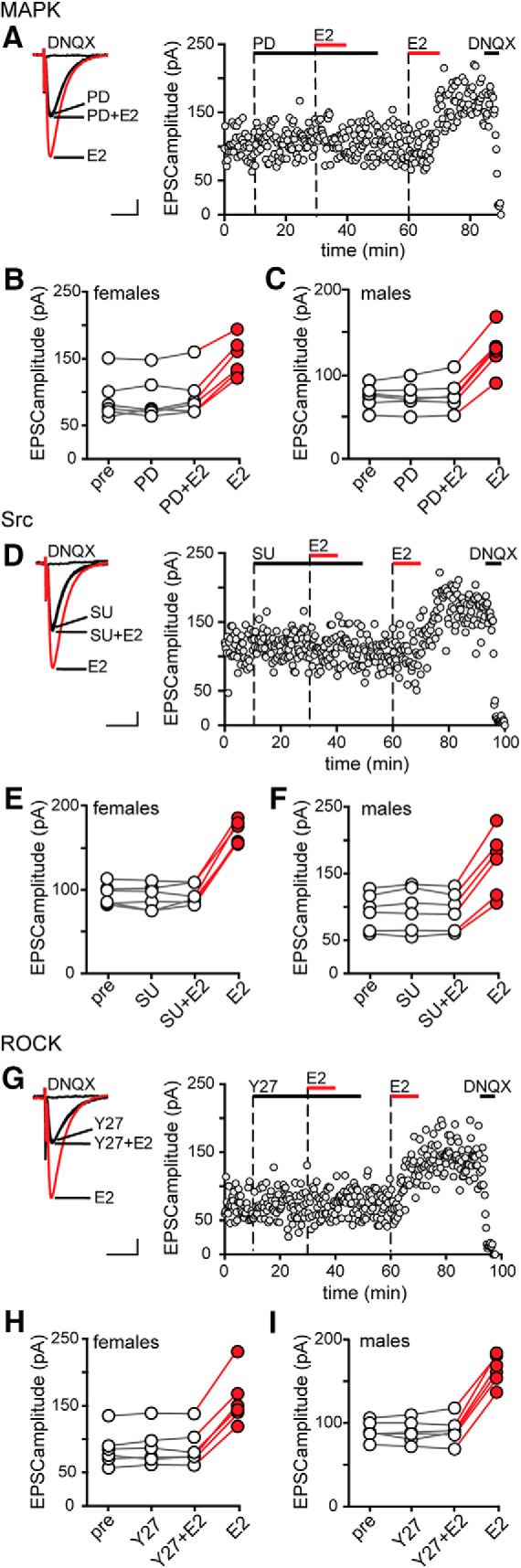

Previous studies have implicated ROCK (Murakoshi et al., 2011; Briz et al., 2015), Src (Lu et al., 1998), and MAPK (English and Sweatt, 1997) in potentiation of excitatory synapses in CA1, including a role for ROCK in E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males (Kramár et al., 2009). Therefore, we tested whether each of these kinases is required for acute E2 potentiation of synaptic transmission and we investigated sex differences. As in experiments with PKA inhibitors, MAPK, Src, or ROCK inhibitors were applied after establishing baseline values for EPSC amplitude and E2 was applied for 10 min in the presence of the inhibitor and then again after inhibitor washout to check for E2 responsiveness in each recorded cell. Within-cell t tests were used to determine whether a recording was E2-responsive.

Inhibiting MAPK with PD98059 (PD, 50 μm) blocked E2-induced EPSC potentiation in all 6 E2-responsive cells among 10 recordings from females (Fig. 3A,B) and all 6 E2-responsive cells among 11 recordings from males (Fig. 3C). The magnitude of potentiation by E2 following PD washout (females: 65 ± 10%, males: 69 ± 5%) was not different from that with E2 alone (unpaired t tests, p > 0.10). Similarly, inhibiting Src kinase with SU6656 (SU, 10 μm) blocked E2-induced EPSC potentiation in the 6 E2-responsive cells among 13 recordings from females (Fig. 3D,E) and the 6 E2-responsive cells among 11 recordings from males (Fig. 3F) and the magnitude of potentiation by E2 following SU washout (females: 80 ± 4%, males: 79 ± 3%) was not different from that with E2 alone (unpaired t tests, p > 0.10). Finally, inhibiting ROCK with Y27632 (Y27, 30 μm) also blocked E2-induced EPSC potentiation in the 6 E2-responsive cells among 11 recordings from females (Fig. 3G,H) and the 6 E2-responsive cells among 12 recordings from males (Fig. 3I) and the magnitude of potentiation after Y27 washout (females: 83 ± 6%, males: 81 ± 6%) was also not different from that with E2 alone (unpaired t tests, p > 0.10). None of these inhibitors had any effect on EPSC amplitude on their own (PD: 1 ± 3%, SU: −1 ± 2%, Y27: 1 ± 2%). Together, these experiments demonstrated that MAPK, Src, and ROCK are each required for initiation of E2-induced EPSC potentiation in both sexes.

Figure 3.

MAPK, Src and ROCK are each required for initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in females and males. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (PD, 50 μm) was applied before E2 in females and a second application of E2 confirmed E2 responsiveness. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in D and G). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with PD98059 in females (n = 6). Points in red represent a significant difference in EPSC amplitude compared with the preceding condition (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in C, E, F, H, and I). C, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with PD98059 in males (n = 6). PD98059 blocked E2-induced potentiation in both sexes. D, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the Src inhibitor SU6656 (SU, 10 μm) was applied before E2 in females. E, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with SU6656 in females (n = 6). F, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with SU6656 in males (n = 6). SU6656 blocked E2-induced potentiation in both sexes. G, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Y27, 30 μm) was applied before E2 in females. H, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with Y27632 in females (n = 6). I, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with Y27632 in males (n = 6). Y27632 blocked E2-induced potentiation in both sexes. Scale bars, 25 pA, 25 ms.

PKA, MAPK, Src, and ROCK are not required for maintenance of E2-induced potentiation in either sex

To study mechanisms underlying the maintenance of E2-induced synaptic potentiation, we investigated whether inhibitors of PKA, MAPK, Src, or ROCK affect E2-induced EPSC potentiation after it was established. In separate experiments, we applied the same kinase inhibitors as above following stabilization of E2-induced potentiation in responsive cells from both sexes. This showed that inhibitors of PKA, MAPK, Src, or ROCK each failed to affect potentiated EPSCs in either females or males (H89: females: 7 cells Fig. 4A,B, males: 6 cells Fig. 4C; PD: females: 6 cells Fig. 4D,E, males: 5 cells Fig. 4F; SU: females: 4 cells Fig. 4G,H, males: 5 cells Fig. 4I; Y27: females: 5 cells Fig. 4J,K, males: 6 cells Fig. 4L). Therefore, ongoing activities of PKA, MAPK, Src, and ROCK are not required to maintain E2-induced potentiation once it has been established.

Figure 4.

PKA, MAPK, Src, and ROCK are not required for maintenance of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in either sex. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the PKA inhibitor H89 (1 μm) was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in D, G, and J). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with H89 in females (n = 7). Points in red represent a significant difference in EPSC amplitude following E2 (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in C, E, F, H, I, K, and L). C, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with H89 in males (n = 6). H89 had no effect on potentiated EPSCs in either sex. D, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (PD, 50 μm) was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. E, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with PD98059 in females (n = 6). F, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with PD98059 in males (n = 5). PD98059 had no effect on potentiated EPSCs in either sex. G, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the Src inhibitor SU6656 (SU, 10 μm) was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. H, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with SU6656 in females (n = 4). I, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with SU6656 in males (n = 5). SU6656 had no effect on potentiated EPSCs in either sex. J, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Y27, 30 μm) was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. K, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with Y27632 in females (n = 5). L, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with Y27632 in males (n = 6). Y27 had no effect on potentiated EPSCs in either sex. Scale bars, 25 pA, 25 ms.

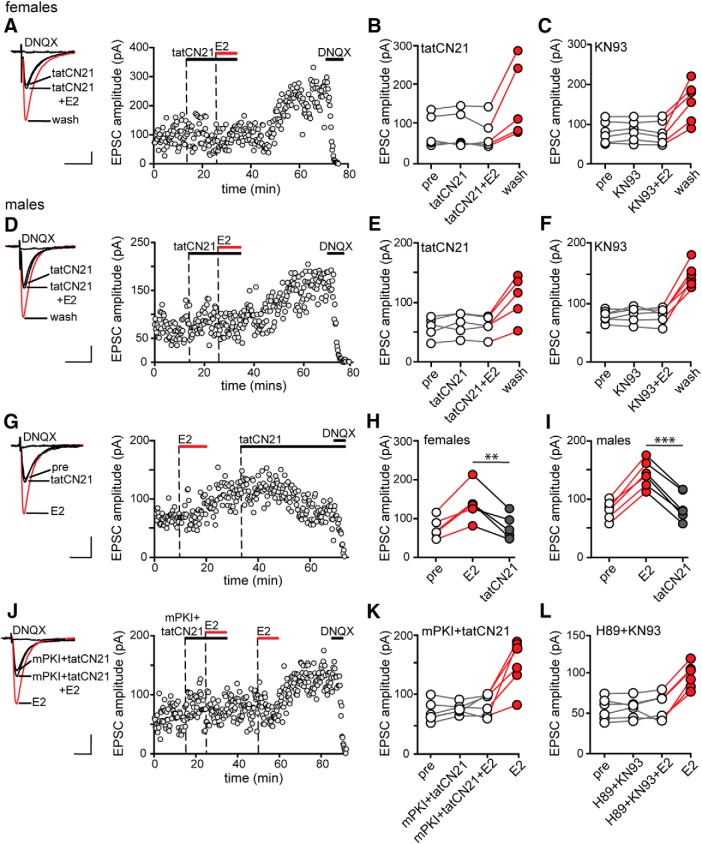

CaMKII is required for the expression and maintenance, but not initiation, of E2-induced potentiation of excitatory synapses in both sexes

CaMKII is one of the most extensively studied kinases in the context of synaptic potentiation. CaMKII has been shown to translocate and immobilize AMPARs at the postsynaptic density (Opazo et al., 2010) and to phosphorylate Ser 831 of the AMPAR subunit GluA1 to increase single-channel conductance (Poncer et al., 2002), both of which can contribute to synaptic potentiation. We tested the involvement of CaMKII in E2-induced potentiation using the membrane-permeant CaMKII inhibitors tatCN21 (1 μm) and KN93 (1 μm), which inhibit CaMKII activity through different mechanisms. In one set of experiments, we applied CaMKII inhibitors before applying E2 in the presence of the inhibitor. In other experiments, tatCN21 was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. Identical experiments were performed in males and females.

In females, tatCN21 by itself had no effect on baseline EPSCs and E2 applied in the presence of tatCN21 failed to increase EPSC amplitude. However, in 5 of 7 recordings, EPSC amplitude measured 10–15 min after tatCN21 and E2 were washed out increased by 97 ± 9% without a second application of E2 (Fig. 5A,B). Identical experiments with KN93 confirmed tatCN21 results. E2 failed to potentiate EPSCs in the presence of KN93, but 10–15 min after KN93 and E2 were washed out, EPSC amplitude increased by 101 ± 16% in 6 of 10 recordings in females (Fig. 5C). Likewise, in males, tatCN21 appeared to block E2-induced EPSC potentiation, but 10–15 min after tatCN21 and E2 washout, EPSCs increased by 81 ± 13% in 5 of 8 recordings without a second E2 application (Fig. 5D,E). KN93 also appeared to block E2-induced EPSC potentiation in males, but EPSC amplitude increased by 73 ± 3% in 6 of 12 recordings after KN93 and E2 washout (Fig. 5F). In both sexes and with both inhibitors, the proportion of cells that responded to E2 (all p-values > 0.1, Fisher's exact tests) and the magnitude of EPSC potentiation (all p-values > 0.1, unpaired t tests) were similar to those obtained in experiments with E2 alone.

Figure 5.

CaMKII is required for expression and maintenance of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in both sexes. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which the CaMKII inhibitor tatCN21 (1 μm) was applied before applying E2 in females. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in D, G, and J). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with tatCN21 in females (n = 5). Points in red represent a significant difference in EPSC amplitude compared with the preceding condition (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in C, E, F, H, I, K, and L). C, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with KN93 in females (n = 6). D, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which tatCN21 (1 μm) was applied before applying E2 in males. E, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with tatCN21 in males (n = 5). F, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with KN93 (1 μm) in males (n = 6). In both sexes, inhibiting CaMKII masked rather than blocked E2-induced potentiation. G, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which tatCN21 (1 μm) was applied after E2-induced potentiation was established. H, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments in females where tatCN21 was applied after E2 (n = 5). Points in gray indicate a significant difference in EPSC amplitude following tatCN21 (also in I, paired t test, ** indicates p < 0.01). I, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments in males where tatCN21 was applied after E2 (n = 5, paired t test, *** indicates p < 0.001). In both sexes, inhibiting CaMKII reversed E2-induced potentiation of EPSCs. J, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in males in which mPKI (0.5 μm) and tatCN21 (1 μm) were applied together before applying E2. K, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with mPKI and tatCN21 (n = 6). L, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with KN93 (1 μm) and H89 (1 μm) (n = 6). In males, inhibiting PKA and CaMKII together blocked E2-induced potentiation. Scale bars, 25 pA, 25 ms.

The results of experiments with CaMKII inhibitors suggested that inhibiting CaMKII masked EPSC potentiation rather than inhibited it. To rule out alternative possibilities, we did three additional experiments. First, we modified the protocol to extend tatCN21 for an additional 10 min after washing out E2. Consistent with previous results, EPSC amplitude increased only 10–15 min after washing out tatCN21, in both females (three of five recordings) and males (three of five recordings) (data not shown). In a second set of experiments, we continued KN93 application after E2 (for up to 40 min) and never observed EPSC potentiation in either females (six recordings) or males (six recordings) (data not shown). In the last of these control experiments, we applied tatCN21 alone for 20–25 min and then washed it out, which had no effect on EPSC amplitude (two recordings in males, data not shown). Therefore, the increase in EPSC amplitude observed following washout of E2 plus a CaMKII inhibitor was not an artifact of inhibitor washout and instead indicates that CaMKII activity is required for the expression and not initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation.

Next, to test whether CaMKII is required for maintenance of E2-induced synaptic potentiation, we applied tatCN21 after potentiation was established (Fig. 5G). Consistent with a role for CaMKII in maintaining potentiated EPSCs, tatCN21 reversed E2-induced potentiation in both sexes. In females, tatCN21 decreased EPSC amplitude from 83 ± 13% above baseline to 5 ± 3% above baseline in 5 of 5 E2-responsive recordings (paired t test, t(4) = 4.9, p = 0.0075) (Fig. 5H). Results were similar in males, where tatCN21 decreased EPSC amplitude from 76 ± 7% above baseline to 8 ± 8% above baseline in 6 of 6 E2-responsive recordings (paired t test, t(5) = 13.78, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5I). These results showed that, in both sexes, CaMKII activity is required not only for initial expression but also ongoing maintenance of E2-induced synaptic potentiation.

PKA and CaMKII cooperate to initiate E2-induced potentiation of excitatory synapses in males

Experiments with mPKI and H89 indicated that PKA by itself is not required for initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males (Fig. 2E,F). Previous studies have shown that, although PKA is not required for many forms of early LTP induction, it can facilitate the activity of other kinases, including CaMKII (Blitzer et al., 1998), by inhibiting protein phosphatase 1 and thereby indirectly contribute to LTP. To investigate whether PKA might play a similar role in E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males, we tested whether inhibiting both PKA and CaMKII simultaneously could block E2-induced potentiation.

In contrast to the results obtained with mPKI or tatCN21 alone, each of which failed to block E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males (Figs. 2E,F, 5D,E), coapplication of these inhibitors blocked initiation of potentiation in males; a second application of E2 after inhibitor washout potentiated EPSCs in 6 of 10 recordings (Fig. 5J,K), confirming that they were E2 responsive. Identical experiments with H89 (PKA inhibitor) and KN93 (CaMKII inhibitor) showed the same results. Coapplication of H89 and KN93 in males also blocked E2-induced potentiation in the 6 E2-responsive cells of 8 recordings (Fig. 5L). These experiments indicate that, whereas PKA is not absolutely required for E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males, it does play a role in cooperation with, and possibly by facilitating activity of, CaMKII.

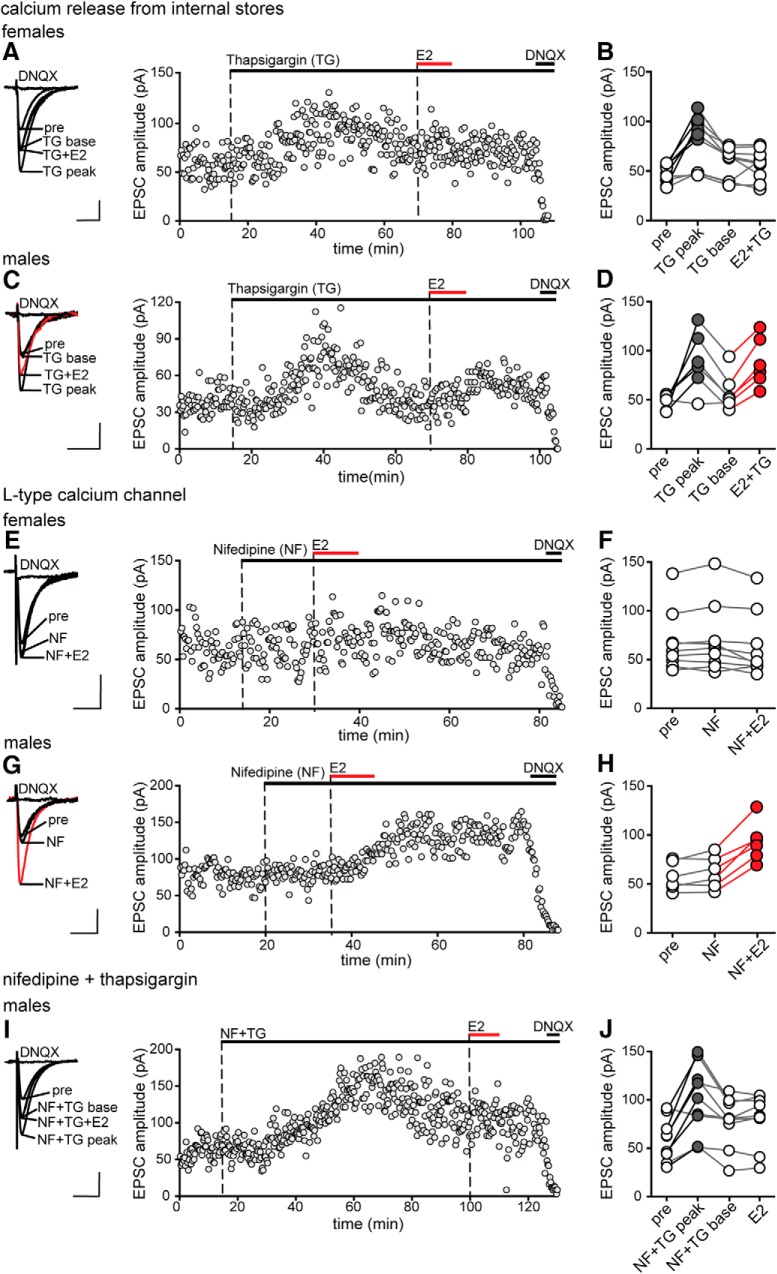

Sex differences in the requirement of internal calcium stores and L-type calcium channels in E2-induced synaptic potentiation

CaMKII activation likely requires an increase in intracellular calcium. Because NMDA receptors were blocked in our experiments, we focused on two alternative calcium sources: internal stores and L-type calcium channels. In separate experiments, we used either thapsigargin (1 μm) to deplete internal calcium stores or nifedipine (10 μm) to block L-type calcium channels. Thapsigargin by itself produced a transient (10–30 min) increase in EPSC amplitude, which was similar in magnitude in both females (70 ± 18%) and males (74 ± 23%). E2 was applied in the continued presence of thapsigargin after EPSCs returned to baseline. Nifedipine by itself had no effect on baseline EPSCs and E2 was also applied in the presence of the inhibitor. Identical experiments were done in females and males.

Experiments with thapsigargin showed that, in females but not in males, depletion of internal calcium stores blocked the initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation. In females, E2 applied in the presence of thapsigargin failed to increase EPSC amplitude in any of 9 recordings (Fig. 6A,B). In contrast, in males, E2 applied in the presence of thapsigargin potentiated EPSC amplitude in 6 of 9 cells by 62 ± 6% (Fig. 6C,D). Similarly, inhibition of L-type calcium channels blocked E2-induced potentiation in females but not in males. In females, E2 failed to potentiate EPSCs in the presence of nifedipine in any of 9 recordings (Fig. 6E,F) whereas, in males, even in the presence of nifedipine, E2 increased EPSC amplitude in 6 of 9 cells, by 66 ± 11% (Fig. 6G,H). Parameters of E2-induced potentiation in thapsigargin or in nifedipine in males were statistically similar to potentiation with E2 alone (89 ± 16%, 11 of 18 cells) (unpaired t tests, p-values >0.10).

Figure 6.

Sex differences in the requirement of calcium release from internal stores and L-type calcium channels during E2-induced synaptic potentiation. A, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which thapsigargin (TG, 1 μm) was applied before E2 in females. Each point is an individual sweep and DNQX (25 μm) applied at the end of the experiment eliminated EPSCs (also in C, E, G, and I). B, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2 experiments done with TG (n = 9) showing that E2 failed to potentiate EPSC amplitude in the presence of TG in females. TG alone transiently increased EPSC amplitude in most cells (also in males, C), indicated by gray points (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in D). C, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which TG was applied before E2 in males. D, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with TG (n = 6) showing that E2 potentiates EPSCs in the presence of TG in males. Points in red indicate a significant difference from the preceding condition (unpaired t test, p < 0.05; also in H). E, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which nifedipine (NF, 10 μm) was applied before E2 in females. F, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2 experiments done with NF (n = 9) showing that E2 failed to potentiate EPSC amplitude in the presence of NF in females. G, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in which NF was applied before E2 in males. H, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2-responsive experiments done with NF (n = 6) showing that E2 potentiates EPSCs in the presence of NF in males. I, Individual traces and time course of synaptic potentiation in a representative experiment in males where NF and TG were applied together before E2. Similar to results with TG alone (see A and C), EPSC amplitude increased transiently in the presence of TG+NF. J, Group EPSC amplitude data for E2 experiments done with TG+NF (n = 9) showing that E2 failed to potentiate EPSC amplitude in the presence of TG+NF in males. Gray points indicate a significant difference from baseline (unpaired t test, p < 0.05). Scale bars, 25 pA, 25 ms.

We hypothesized that, similar to the cooperative action we observed between PKA and CaMKII during E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males (Fig. 5J–L), calcium release from internal stores and L-type calcium channels might also cooperate during E2-induced potentiation in males. To test this possibility, we blocked both calcium release from internal stores and L-type calcium channels simultaneously. Similar to results with thapsigargin alone, applying nifedipine and thapsigargin together produced a transient increase in EPSC amplitude (75 ± 13%) and, when EPSC amplitude stabilized, E2 was applied in the continued presence of both inhibitors.

Although neither depleting internal calcium stores nor blocking L-type calcium channels alone was sufficient to inhibit E2 potentiation of EPSCs in males, inhibiting both together did block potentiation. E2 failed to potentiate EPSCs in any of 9 recordings in which thapsigargin and nifedipine were applied together (Fig. 6I,J). Therefore, in contrast to females, in which both calcium release from internal stores and L-type calcium channels are required for E2-induced synaptic potentiation, these two calcium sources may be able to compensate for each other in E2-induced potentiation in males. Together with a similar result in experiments using PKA and CaMKII inhibitors, this suggests a pattern of parallel signaling leading to synaptic potentiation in males that is distinct from signaling leading to the same outcome in females.

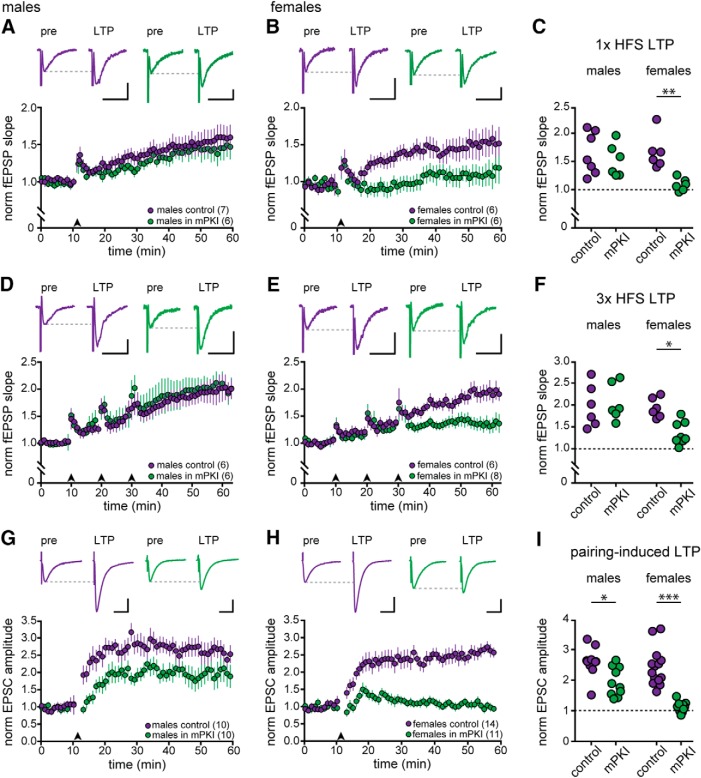

Sex difference in the involvement of PKA in LTP

Experiments with mPKI and H89 showed a sex difference in the requirement for PKA in initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation (Fig. 2). This raises the question of whether a sex difference in involvement of PKA is specific to E2 potentiation or if it could generalize to other forms of synaptic plasticity. The involvement of PKA in LTP of CA3–CA1 synapses has been studied extensively and depends on the LTP induction protocol and/or age of animals used. However, no studies have compared the role of PKA in both sexes. Therefore, we investigated the possibility of a sex difference in PKA involvement in LTP. We used three protocols: HFS-induced LTP using 1× or 3× 100 Hz stimulation for 1 s, the early component of which is widely reported to be insensitive to inhibition of PKA (Frey et al., 1993; Huang and Kandel, 1994; Abel et al., 1997; Woo et al., 2002; Park et al., 2014) and LTP induced by pairing postsynaptic depolarization to 0 mV with 200 presynaptic stimulations at 1.4 Hz, which is reported to be modestly sensitive to PKA inhibition based on recordings in males (Otmakhova et al., 2000). Identical experiments were performed in both sexes with or without mPKI (0.5 μm) in the bath.

Experiments with 1× HFS showed that PKA was required for LTP in females but not in males. In males, 1× HFS increased fEPSP slope by 62 ± 15% above baseline in control recordings (n = 7; paired t test, t(6) = 5.86, p = 0.001) and by 43 ± 15% in mPKI (n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 5.15, p = 0.004; Fig. 7A). In females, 1× HFS also increased fEPSP slope in control recordings, by 60 ± 15% above baseline (n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 4.714, p = 0.005), but failed to significantly increase fEPSP slope in the presence of mPKI (13 ± 11%, n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 1.62, p > 0.10; Fig. 7B). Two-way ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction between sex and mPKI in the magnitude of LTP induced by 1× HFS (F(1,21) = 4.6, p = 0.043) and post hoc tests showed that results in female mPKI recordings were significantly different from female controls (p = 0.009; Fig. 7C) and both male groups (p-values < 0.03), which were not different from each other (all p-values > 0.10). To confirm that PKA inhibition does not block 1× HFS-induced LTP in males, we performed additional experiments with 1 μm mPKI, which also failed to block LTP in males (51 ± 17%, n = 3, data not shown).

Figure 7.

Sex differences in the requirement for PKA in long term potentiation. A, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized fEPSP slope for 1× HFS LTP experiments in males (n = 7 control, purple; n = 6 mPKI, green). Scale bars, 0.2 mV, 25 ms (also in B, D, and E). B, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized fEPSP slope for all 1× HFS LTP experiments in females (n = 6 control, purple; n = 6 mPKI, green). C, Normalized increase in fEPSP slope for all 1× HFS LTP experiments where the magnitude of potentiation is shown separately for each control and mPKI experiment in males and females. PKA inhibition had no effect on 1× HFS LTP in males, but blocked 1× HFS LTP in females (Bonferroni post hoc test, ** indicates p < 0.01). D, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized fEPSP slope for all 3× HFS LTP experiments in males (n = 6 control, purple; n = 6 mPKI, green). E, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized fEPSP slope for all 3× HFS LTP experiments in females (n = 6 control, purple; n = 8 mPKI, green). F, Normalized increase in fEPSP slope for all 3× HFS LTP experiments in which the magnitude of potentiation is shown separately for each control and mPKI experiment in males and females. PKA inhibition had no effect on 3× HFS LTP in males, but attenuated 3× HFS LTP in females (Bonferroni post hoc test, *p < 0.05). G, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized EPSC amplitude for all pairing-induced LTP experiments in males (n = 10 control, purple; n = 10 mPKI, green). Scale bars, 50 pA, 25 ms (also in H). H, Representative individual traces and time course of mean ± SEM normalized EPSC amplitude for all pairing-induced LTP experiments in females (n = 14 control, purple; n = 11 mPKI, green). I, Normalized increase in EPSC amplitude for all pairing induced LTP experiments in which the magnitude of potentiation is shown separately for each control and mPKI experiment in males and females. PKA inhibition attenuated pairing-induced LTP in males, but blocked pairing-induced LTP in females (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, Bonferroni post hoc test).

Similar to results with 1× HFS, 3× HFS also showed a sex difference in the involvement of PKA in LTP; however, in these experiments, mPKI decreased LTP in females but did not block it. In males, 3× HFS significantly increased fEPSP slope by 97 ± 19% above baseline in control recordings (n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 4.76, p = 0.005) and by 101 ± 19% in mPKI (n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 8.15, p < 0.001; Fig. 7D). In female controls, 3× HFS increased fEPSP slope by 86 ± 11% (n = 6; paired t test, t(5) = 5.75, p = 0.002), similar to males, but by only 35 ± 8% in the presence of mPKI (n = 8; paired t test, t(7) = 4. 71, p = 0.002; Fig. 7E). As in the case of 1× HFS-induced LTP, two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction between sex and mPKI in the magnitude of LTP induced by 3× HFS (F(1,22) = 5.46, p = 0.028) and post hoc tests showed that female mPKI recordings were significantly different from female controls (p = 0.04; Fig. 7F) and both male groups (p-values < 0.03), which were not different from each other (all p-values > 0.10).

Finally, we tested whether a distinct type of LTP, pairing-induced LTP, also differs by sex in its dependence on PKA. These experiments showed that whereas pairing-induced LTP was modestly attenuated by PKA inhibition in males, consistent with previous reports, it was abolished by PKA inhibition in females. The pairing protocol potentiated EPSCs by 148 ± 19% above baseline in male control recordings (n = 10, paired t test, t(9) = 5.74, p < 0.001), but by only 100 ± 15% above baseline in the presence of mPKI (n = 10, paired t test, t(9) = 5.08, p < 0.001; Fig. 7G). In females, pairing potentiated EPSCs by 160 ± 17% above baseline in controls (n = 14, paired t test, t(13) = 7.04, p < 0.001), similar to males, but failed to potentiate EPSCs in the presence of mPKI (5 ± 5% above baseline, n = 11, paired t test, t(10) = 1.38, p > 0.10; Fig. 7H). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant interaction between sex and mPKI (F(1,41) = 6.96, p = 0.01). Post hoc tests showed that mPKI decreased LTP in both sexes (males p = 0.04, females p < 0.001; Fig. 7I) and that female mPKI differed from all other groups (all p-values < 0.001). Therefore, whereas PKA contributes to pairing-induced LTP in males, it is required for pairing-induced LTP in females. Together with the effects of PKA inhibition on HFS-induced LTP and E2-induced synaptic potentiation, these results suggest a generalizable sex difference in the requirement for PKA in hippocampal synaptic potentiation.

Discussion

In this study, we found that multiple aspects of the molecular signaling that underlies potentiation of excitatory synapses in the hippocampus differ between the sexes. Specifically, PKA is required for initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation in females but not males and both L-type calcium channels and calcium release from internal stores are required for E2-induced potentiation in females, whereas in males, either of these calcium sources is sufficient. In addition, the sex difference in PKA requirement extends to multiple forms of LTP, suggesting that this difference may be generalizable in mechanisms of synaptic potentiation. In contrast, other aspects of molecular signaling involved in E2-induced synaptic potentiation are similar between the sexes. MAPK, Src, and ROCK are each required for initiation and CaMKII is required for expression and maintenance of potentiation in both sexes. Interestingly, despite sex differences in molecular signaling, the degree of potentiation achieved in LTP or after E2 is essentially identical between the sexes. Therefore, these findings extend the concept of latent sex differences (Oberlander and Woolley, 2016) in which distinct underlying mechanisms converge to common functional endpoints in males and females.

Kinase signaling in E2-induced and activity-dependent synaptic potentiation

Considering parallels between E2-induced potentiation and LTP may give insight into intracellular signaling that leads to synaptic potentiation. In this regard, it is important to note that the male-female differences we observed were specific to synaptic potentiation. None of the kinase inhibitors that we used nor nifedipine altered baseline synaptic transmission in either sex. Depleting internal calcium stores with thapsigargin transiently increased EPSC amplitude similarly in both sexes.

The three kinases that we found are essential for initiation of E2-induced synaptic potentiation, MAPK, Src, and ROCK, have long been known to play important roles in LTP. For example, MAPK facilitates AMPAR trafficking and insertion at synapses during LTP (Qin et al., 2005; Patterson et al., 2010) and Src activates ROCK to inhibit cofilin, which promotes actin polymerization and increases dendritic spine volume (Koleske, 2013). MAPK, Src, and ROCK are likely to function similarly in E2-induced synaptic potentiation, as has been shown directly for estrogen receptor β activation of ROCK, which promotes actin polymerization in dendritic spines in males (Kramár et al., 2009).

Unlike MAPK, Src, and ROCK, CaMKII appears to function differently in LTP and E2-induced potentiation. Inhibiting CaMKII blocks initiation of early LTP (Malinow et al., 1989; Otmakhov et al., 1997; Lisman et al., 2012). However, we found that, although E2-induced potentiation was not apparent in the presence of CaMKII inhibitors, EPSC amplitude began to increase shortly after inhibitor washout, indicating that potentiation had been initiated but could not be expressed. One difference between our E2 experiments and most LTP studies is that we blocked NMDARs to focus exclusively on AMPAR modulation, whereas calcium influx through NMDARs is a critical source of increased intracellular calcium for LTP initiation. Although others have shown that CaMKII interacts with GluN2B to promote maintenance of LTP (Sanhueza et al., 2011; Barcomb et al., 2016), the 1 μm tatCN21 that we used is well below the 20 μm shown to disrupt this interaction. In combination with the fact that NMDARs were blocked in our experiments, it is unlikely that CaMKII interaction with GluN2B is relevant to the tatCN21-induced reversal of E2-induced potentiation that we observed. The requirement for CaMKII in expression of E2-induced potentiation may instead reflect CaMKII's role in trapping newly inserted AMPARs at synapses through phosphorylation of TARPs such as stargazin (Chen et al., 2000; Tomita et al., 2005; Opazo et al., 2010).

In contrast to other kinases, PKA is more commonly associated with late LTP (Frey et al., 1993; Huang and Kandel, 1994; Abel et al., 1997), although some studies indicate that early LTP can be sensitive to PKA inhibition (Blitzer et al., 1998; Otmakhova et al., 2000; Yasuda et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006). Most of these previous studies either used males or sex was not noted, raising the possibility that some discrepancies in the literature are related to sex differences.

One potential explanation for the sex differences in PKA requirement that we found derives from the idea that PKA inhibits phosphatases that normally constrain the activity of other kinases such as CaMKII and thereby permits LTP but does not directly cause it (Blitzer et al., 1998). That inhibition of PKA and CaMKII together blocks E2-induced potentiation in males suggests that PKA may play a similar role in E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males. If PKA acts as a gate for E2-induced potentiation, the sex difference in sensitivity of potentiation to PKA inhibition could be related to differences in basal PKA activity. For example, higher basal PKA activity in males might permit activity of other kinases that are essential for potentiation without E2 modulation of PKA. In females, lower basal PKA activity might fail to establish this permissive state and require stimulation by E2 to achieve it. Studies in cardiomyocytes support this possibility. Both basal cAMP levels and PKA activity are lower in female than male cardiomyocytes due at least in part to females' higher levels of phosphodiesterase (PDE) 4B, which hydrolyzes cAMP (Parks et al., 2014). However, whether this sex difference extends to the hippocampus is unknown. There is evidence that PDE4B inhibition promotes early LTP in the hippocampus (Titus et al., 2016; Campbell et al., 2017), but this has been tested only in males.

It is also possible that sex differences in the levels of extranuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) that mediate acute E2 signaling or the coupling of ERs to downstream effectors of synaptic plasticity differ between the sexes (Wang et al., 2018). Consistent with this idea, we have shown previously that distinct combinations of ERs mediate E2-induced synaptic potentiation in males versus females (Oberlander and Woolley, 2016). Heterogeneous distributions of extranuclear ERs may also contribute to the consistent finding, here and previously (Wong and Moss, 1992; Smejkalova and Woolley, 2010), that only a subset of recordings is acutely responsive to E2.

Sex differences in the requirement for intracellular calcium sources

Kinases important in LTP initiation are generally activated by calcium, often through NMDAR channels. As noted above, however, NMDARs were blocked in our experiments. When we tested the requirement for two alternative calcium sources, L-type calcium channels and release from internal stores, we found that either of these is sufficient to support E2-induced potentiation in males, whereas in females both are required. This difference could reflect parallel signaling in males such that one calcium source can compensate for the other and/or it could arise from differences in regulation of calcium sources. For example, considering the suggestion above that basal cAMP levels and PKA activity might be higher in males, it is possible that males' basal state also includes PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the inositol triphosphate receptor to increase calcium levels (Wagner et al., 2008). In this way, sex differences in the dependence of potentiation on PKA and calcium release from stores may be mechanistically related.

Our results also indicated a role for L-type calcium channels in E2-induced potentiation. Although L-type channels are high-voltage activated and might not be expected to contribute to calcium influx at the relatively negative holding potential used for our experiments (−70 mV), others have shown that L-type channels are active at membrane potentials at or near rest, particularly in adult animals and at elevated temperatures as in our experiments (Magee et al., 1996; Radzicki et al., 2013). There is literature on acute E2 modulation of L-type channels focused on activation of kinases involved in neuroprotection, including Src and Erk/MAPK (Wu et al., 2005; Zhao and Brinton, 2007; Vega-Vela et al., 2017). Our observation that L-type calcium channels and calcium release from internal stores are both required for E2-induced potentiation in females suggests that synaptic potentiation in females requires at least two distinct intracellular cascades. However, the nature of this distinction is unknown. It could be that different essential kinases are activated by distinct calcium sources in females or the distinction could reflect spatial or temporal separation of essential signals. Future studies, such as with calcium imaging, may help to resolve these questions.

Implications of latent sex differences in intracellular signaling

Studying acute E2-induced synaptic plasticity is valuable as a model for understanding how estrogens synthesized in the brain, including the hippocampus (Hojo et al., 2004; Tabatadze et al., 2014; Sato and Woolley, 2016), act locally to modulate neural circuits and behavior. For example, recent studies indicate that brain-derived estrogens promote hippocampus-dependent memory, both in female mice (Tuscher et al., 2016) and postmenopausal women (Bayer et al., 2015). Despite evidence that neurosteroid estrogen levels are comparable between the sexes (Sato and Woolley, 2016) or higher in males (Hojo et al., 2009), few studies have compared the actions of estrogens in males and females.

The focus on females in neurosteroid estrogen studies stands in contrast to the overrepresentation of males in basic neuroscience (Beery and Zucker, 2011), including in studies of LTP. Our findings that males and females differ in the involvement of a well studied kinase such as PKA and intracellular calcium signaling suggest that sex differences in mechanisms related to synaptic plasticity may be more widespread than currently appreciated. Furthermore, the mechanistic differences we observed are latent sex differences in that the degree of potentiation was the same between males and females. Therefore, similar outcomes in each sex cannot be presumed to indicate the same underlying mechanisms. This is relevant particularly in the context of therapeutic development because manipulating a specific molecular pathway may have distinct outcomes in each sex, even when males and females do not appear to differ.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01 MH095248 and R01 MH113189 to C.S.W.).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abel T, Nguyen PV, Barad M, Deuel TA, Kandel ER, Bourtchouladze R (1997) Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell 88:615–626. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81904-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcomb K, Hell JW, Benke TA, Bayer KU (2016) The CaMKII/GluN2B protein interaction maintains synaptic strength. J Biol Chem 291:16082–16089. 10.1074/jbc.M116.734822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer J, Rune G, Schultz H, Tobia MJ, Mebes I, Katzler O, Sommer T (2015) The effect of estrogen synthesis inhibition on hippocampal memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology 56:213–225. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, Zucker I (2011) Sex bias in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:565–572. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi R, Broutman G, Foy MR, Thompson RF, Baudry M (2000) The tyrosine kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediate multiple effects of estrogen in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:3602–3607. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitzer RD, Connor JH, Brown GP, Wong T, Shenolikar S, Iyengar R, Landau EM (1998) Gating of CaMKII by cAMP-regulated protein phosphatase activity during LTP. Science 280:1940–1942. 10.1126/science.280.5371.1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz V, Zhu G, Wang Y, Liu Y, Avetisyan M, Bi X, Baudry M (2015) Activity-dependent rapid local RhoA synthesis is required for hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 35:2269–2282. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2302-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SL, van Groen T, Kadish I, Smoot LHM, Bolger GB (2017) Altered phosphorylation, electrophysiology, and behavior on attenuation of PDE4B action in hippocampus. BMC Neurosci 18:77. 10.1186/s12868-017-0396-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA (2000) Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature 408:936–943. 10.1038/35050030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English JD, Sweatt JD (1997) A requirement for the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in hippocampal long term potentiation. J Biol Chem 272:19103–19106. 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Huang YY, Kandel ER (1993) Effects of cAMP simulate a late stage of LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Science 260:1661–1664. 10.1126/science.8389057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Moss RL (1996) 17 beta-estradiol potentiates kainate-induced currents via activation of the cAMP cascade. J Neurosci 16:3620–3629. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-11-03620.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y, Hojo Y, Kojima H, Ikeda M, Hotta K, Sato R, Ooishi Y, Yoshiya M, Chung BC, Yamazaki T, Kawato S (2015) Estradiol rapidly modulates synaptic plasticity of hippocampal neurons: involvement of kinase networks. Brain Res 1621:147–161. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo Y, Hattori TA, Enami T, Furukawa A, Suzuki K, Ishii HT, Mukai H, Morrison JH, Janssen WG, Kominami S, Harada N, Kimoto T, Kawato S (2004) Adult male rat hippocampus synthesizes estradiol from pregnenolone by cytochromes P45017alpha and P450 aromatase localized in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:865–870. 10.1073/pnas.2630225100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo Y, Higo S, Ishii H, Ooishi Y, Mukai H, Murakami G, Kominami T, Kimoto T, Honma S, Poirier D, Kawato S (2009) Comparison between hippocampus-synthesized and circulation-derived sex steroids in the hippocampus. Endocrinology 150:5106–5112. 10.1210/en.2009-0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GZ, Woolley CS (2012) Estradiol acutely suppresses inhibition in the hippocampus through a sex-specific endocannabinoid and mGluR-dependent mechanism. Neuron 74:801–808. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER (1994) Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn Mem 1:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleske AJ. (2013) Molecular mechanisms of dendrite stability. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:536–550. 10.1038/nrn3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramár EA, Chen LY, Brandon NJ, Rex CS, Liu F, Gall CM, Lynch G (2009) Cytoskeletal changes underlie estrogen's acute effects on synaptic transmission and plasticity. J Neurosci 29:12982–12993. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3059-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, Yasuda R, Raghavachari S (2012) Mechanisms of CaMKII action in long-term potentiation. Nat Rev Neurosci 13:169–182. 10.1038/nrn3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YM, Roder JC, Davidow J, Salter MW (1998) Src activation in the induction of long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampal neurons. Science 279:1363–1367. 10.1126/science.279.5355.1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Avery RB, Christie BR, Johnston D (1996) Dihydropyridine-sensitive, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels contribute to the resting intracellular Ca2+ concentration of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 76:3460–3470. 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Schulman H, Tsien RW (1989) Inhibition of postsynaptic PKC or CaMKII blocks induction but not expression of LTP. Science 245:862–866. 10.1126/science.2549638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi H, Wang H, Yasuda R (2011) Local, persistent activation of rho GTPases during plasticity of single dendritic spines. Nature 472:100–104. 10.1038/nature09823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander JG, Woolley CS (2016) 17beta-estradiol acutely potentiates glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus through distinct mechanisms in males and females. J Neurosci 36:2677–2690. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4437-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opazo P, Labrecque S, Tigaret CM, Frouin A, Wiseman PW, De Koninck P, Choquet D (2010) CaMKII triggers the diffusional trapping of surface AMPARs through phosphorylation of stargazin. Neuron 67:239–252. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhova NA, Otmakhov N, Mortenson LH, Lisman JE (2000) Inhibition of the cAMP pathway decreases early long-term potentiation at CA1 hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci 20:4446–4451. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04446.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhov N, Griffith LC, Lisman JE (1997) Postsynaptic inhibitors of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II block induction but not maintenance of pairing-induced long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 17:5357–5365. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05357.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park P, Volianskis A, Sanderson TM, Bortolotto ZA, Jane DE, Zhuo M, Kaang BK, Collingridge GL (2014) NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation comprises a family of temporally overlapping forms of synaptic plasticity that are induced by different patterns of stimulation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369:20130131. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks RJ, Ray G, Bienvenu LA, Rose RA, Howlett SE (2014) Sex differences in SR Ca(2+) release in murine ventricular myocytes are regulated by the cAMP/PKA pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol 75:162–173. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson MA, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R (2010) AMPA receptors are exocytosed in stimulated spines and adjacent dendrites in a ras-ERK-dependent manner during long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:15951–15956. 10.1073/pnas.0913875107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncer JC, Esteban JA, Malinow R (2002) Multiple mechanisms for the potentiation of AMPA receptor-mediated transmission by alpha-Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Neurosci 22:4406–4411. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04406.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prange-Kiel J, Wehrenberg U, Jarry H, Rune GM (2003) Para/autocrine regulation of estrogen receptors in hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus 13:226–234. 10.1002/hipo.10075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Zhu Y, Baumgart JP, Stornetta RL, Seidenman K, Mack V, van Aelst L, Zhu JJ (2005) State-dependent ras signaling and AMPA receptor trafficking. Genes Dev 19:2000–2015. 10.1101/gad.342205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radzicki D, Yau HJ, Pollema-Mays SL, Mlsna L, Cho K, Koh S, Martina M (2013) Temperature-sensitive Cav1.2 calcium channels support intrinsic firing of pyramidal neurons and provide a target for the treatment of febrile seizures. J Neurosci 33:9920–9931. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5482-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza M, Fernandez-Villalobos G, Stein IS, Kasumova G, Zhang P, Bayer KU, Otmakhov N, Hell JW, Lisman J (2011) Role of the CaMKII/NMDA receptor complex in the maintenance of synaptic strength. J Neurosci 31:9170–9178. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1250-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato SM, Woolley CS (2016) Acute inhibition of neurosteroid estrogen synthesis suppresses status epilepticus in an animal model. Elife 5:e12917. 10.7554/eLife.12917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smejkalova T, Woolley CS (2010) Estradiol acutely potentiates hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission through a presynaptic mechanism. J Neurosci 30:16137–16148. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4161-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabatadze N, Sato SM, Woolley CS (2014) Quantitative analysis of long-form aromatase mRNA in the male and female rat brain. PLoS One 9:e100628. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyler TJ, Vardaris RM, Lewis D, Rawitch AB (1980) Gonadal steroids: effects on excitability of hippocampal pyramidal cells. Science 209:1017–1018. 10.1126/science.7190730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus DJ, Wilson NM, Freund JE, Carballosa MM, Sikah KE, Furones C, Dietrich WD, Gurney ME, Atkins CM (2016) Chronic cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury is improved with a phosphodiesterase 4B inhibitor. J Neurosci 36:7095–7108. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3212-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Adesnik H, Sekiguchi M, Zhang W, Wada K, Howe JR, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS (2005) Stargazin modulates AMPA receptor gating and trafficking by distinct domains. Nature 435:1052–1058. 10.1038/nature03624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuscher JJ, Szinte JS, Starrett JR, Krentzel AA, Fortress AM, Remage-Healey L, Frick KM (2016) Inhibition of local estrogen synthesis in the hippocampus impairs hippocampal memory consolidation in ovariectomized female mice. Horm Behav 83:60–67. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Vela NE, Osorio D, Avila-Rodriguez M, Gonzalez J, García-Segura LM, Echeverria V, Barreto GE (2017) L-type calcium channels modulation by estradiol. Mol Neurobiol 54:4996–5007. 10.1007/s12035-016-0045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner LE 2nd, Joseph SK, Yule DI (2008) Regulation of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel activity by protein kinase A phosphorylation. J Physiol 586:3577–3596. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Le AA, Hou B, Lauterborn JC, Cox CD, Levin ER, Lynch G, Gall CM (2018) Memory-related synaptic plasticity is sexually dimorphic in rodent hippocampus. J Neurosci 38:7935–7951. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0801-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Moss RL (1992) Long-term and short-term electrophysiological effects of estrogen on the synaptic properties of hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Neurosci 12:3217–3225. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03217.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo NH, Abel T, Nguyen PV (2002) Genetic and pharmacological demonstration of a role for cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated suppression of protein phosphatases in gating the expression of late LTP. Eur J Neurosci 16:1871–1876. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Rowan MJ, Anwyl R (2006) Long-term potentiation is mediated by multiple kinase cascades involving CaMKII or either PKA or p42/44 MAPK in the adult rat dentate gyrus in vitro. J Neurophysiol 95:3519–3527. 10.1152/jn.01235.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TW, Wang JM, Chen S, Brinton RD (2005) 17Beta-estradiol induced Ca2+ influx via L-type calcium channels activates the Src/ERK/cyclic-AMP response element binding protein signal pathway and BCL-2 expression in rat hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Neuroscience 135:59–72. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Barth AL, Stellwagen D, Malenka RC (2003) A developmental switch in the signaling cascades for LTP induction. Nat Neurosci 6:15–16. 10.1038/nn985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadran S, Qin Q, Bi X, Zadran H, Kim Y, Foy MR, Thompson R, Baudry M (2009) 17-beta-estradiol increases neuronal excitability through MAP kinase-induced calpain activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:21936–21941. 10.1073/pnas.0912558106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Brinton RD (2007) Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 1172:48–59. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]