Subclass III SnRK2 kinases play key roles in abscisic acid signaling, which is responsible for maintaining normal metabolism and leaf growth under nonstress conditions.

Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a plant hormone that regulates a diverse range of cellular and molecular processes during development and in response to osmotic stress. In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), three Suc nonfermenting-1-related protein kinase2s (SnRK2s), SRK2D, SRK2E, and SRK2I, are key positive regulators involved in ABA signaling whose substrates have been well studied. Besides reduced drought-stress tolerance, the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant shows abnormal growth phenotypes, such as an increased number of leaves, under nonstress conditions. However, it remains unclear whether, and if so how, SnRK2-mediated ABA signaling regulates growth and development. Here, we show that the primary metabolite profile of srk2d srk2e srk2i grown under nonstress conditions was considerably different from that of wild-type plants. The metabolic changes observed in the srk2d srk2e srk2i were similar to those in an ABA-biosynthesis mutant, aba2-1, and both mutants showed a higher leaf emergence rate than wild type. Consistent with the increased amounts of citrate, isotope-labeling experiments revealed that respiration through the tricarboxylic acid cycle was enhanced in srk2d srk2e srk2i. These results, together with transcriptome data, indicate that the SnRK2s involved in ABA signaling modulate metabolism and leaf growth under nonstress conditions by fine-tuning flux through the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Land plants have to adapt their growth to the prevailing environmental conditions. Many plant hormones, including auxin, cytokinins, gibberellins, and brassinosteroids, play crucial roles in regulating plant growth and development. Extensive molecular biological analyses in the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) have unveiled the biosynthetic, degradative, signaling, and transport pathways of auxin and cytokinin (Schaller et al., 2015). Given their roles in growth and development, Arabidopsis mutants overproducing auxin or cytokinin display abnormal phenotypes (Chaudhury et al., 1993; Zhao et al., 2001), and also show semisterility (Chaudhury et al., 1993), whereas feedback loops in auxin and cytokinin signaling provide a homeostatic mechanism that prevents excessive growth (Schaller et al., 2015). Likewise, gibberellin levels are tightly controlled by their biosynthesis and deactivation to achieve appropriate growth and development (Yamaguchi, 2008). Brassinosteroid biosynthesis is also known to be suppressed by feedback regulation (Wang et al., 2002). Furthermore, plant shoot growth under water-limiting conditions is likely to be actively suppressed rather than merely limited by resources, with the available resources being diverted to enhance root growth. In several plant species, shoot growth is reduced by mild water deficit whereas photosynthesis is maintained until the occurrence of more severe water shortage (Muller et al., 2011).

In contrast with auxin, cytokinins, gibberellins, and brassinosteroids, abscisic acid (ABA) acts as a stress signal to adjust plant growth in response to changes in water availability. ABA plays essential roles in seed maturation and germination, stomatal closure, and stress-responsive gene expression under osmotic stress conditions. ABA is required for embryo growth during the early phase of seed development (Cheng et al., 2002; Frey et al., 2004), but high ABA levels in later developmental phases inhibit embryo growth by suppressing gibberellin signaling (White et al., 2000; Raz et al., 2001). In guard cells, ABA signaling activates the efflux of anion and potassium ions via membrane proteins. This decreases guard cell turgor pressure and volume, leading to stomatal closure, which prevents water loss (Kim et al., 2010), but at the same time reduces the influx and assimilation of CO2. In vegetative tissues under osmotic stress conditions, ABA-dependent and ABA-independent signaling pathways function cooperatively to induce a large number of genes involved in signal transduction and stress tolerance (Yoshida et al., 2014), diverting resources away from growth to enhance stress tolerance.

The biological functions of ABA have mostly been studied in the context of osmotic stress and seed dormancy. However, ABA also modulates growth under nonstress conditions. Endogenous ABA is associated with the maintenance of shoot growth in Arabidopsis and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum; Sharp et al., 2000; LeNoble et al., 2004). Moreover, the endogenous ABA level in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves fluctuates during a day–night cycle, reaching its maximum in the night (Nováková et al., 2005). A literature-based model also illustrated dynamic changes in endogenous ABA levels in both guard cells and the apoplastic spaces that surround them (Tallman, 2004). In association with the diurnal variation of ABA levels, a comparative transcriptome analysis in Arabidopsis showed that the expression of many ABA-responsive genes oscillates diurnally (Mizuno and Yamashino, 2008). Moreover, lack of the circadian regulator, TIME FOR COFFEE, resulted in increased expression of ABA- and drought-related genes and enhanced sensitivity to ABA during germination in Arabidopsis (Sanchez-Villarreal et al., 2013). These studies suggest that ABA signaling plays a role in normal diel cycles, although this remains to be firmly demonstrated.

In this model, established in Arabidopsis, three protein families play key roles in signal perception and transduction of ABA (Cutler et al., 2010; Hubbard et al., 2010; Raghavendra et al., 2010; Weiner et al., 2010). In the absence of ABA, group-A protein phosphatase 2Cs (PP2Cs) interact with and inhibit subclass III sucrose non-fermenting-1–related protein kinase 2s (SnRK2s). When the level of ABA increases in response to endogenous and environmental signals, it is perceived by a group of cytosolic ABA receptors, designated as PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1), PYR1-LIKE (PYL), or REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR (RCAR). Upon binding of ABA, the PYR/PYL/RCAR-type receptors undergo a conformational change that enables them to interact with the PP2Cs, resulting in the release and activation of the SnRK2s. The activated SnRK2s subsequently phosphorylate their substrates, such as ABA-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT (ABRE) BINDING proteins (AREBs)/ABRE BINDING FACTORS (ABFs) and some membrane proteins, to trigger ABA-responsive gene expression and stomatal closure, respectively. Arabidopsis contains 10 SnRK2s divided into three subclasses (I, II, and III). The three subclass III SnRK2s (SRK2D/SnRK2.2, SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1, and SRK2I/SnRK2.3) are strongly activated by ABA (Boudsocq et al., 2004). Consistently, the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant (also referred to as srk2d/e/i or snrk2.2/2.3/2.6) is less drought-stress tolerant and shows greatly reduced sensitivity to ABA during seed germination, seedling growth, stomatal regulation, and gene expression compared to the wild type (Fujii and Zhu, 2009; Fujita et al., 2009; Nakashima et al., 2009).

In addition to extreme ABA-insensitivity, the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant shows an abnormal phenotype under nonstress conditions. Although the plant size was similar to that of the wild type, the number of leaves was significantly increased in the triple mutant compared to wild type and also with the single srk2d, srk2e, and srk2i mutants and double mutants (Fujita et al., 2009). This observation implies that ABA signaling mediated by subclass III SnRK2s negatively regulates leaf growth and related metabolism. The metabolite profile of the nine-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase3 mutant, which is unable to synthesize ABA in response to dehydration, coupled with transcriptomic data revealed the metabolic pathways that are regulated by ABA signaling under dehydration conditions (Urano et al., 2009). The SnRK2-AREB/ABF signaling pathway was recently shown to be important for the transcriptional regulation of α-AMYLASE3 and β-AMYLASE1 to redistribute sugars from starch degradation in response to osmotic stress (Thalmann et al., 2016). However, it remains obscure whether, and if so how, ABA signaling is involved in plant growth and metabolism under nonstress conditions.

In this study, we report that the subclass III SnRK2s involved in ABA signaling mediate primary metabolism and leaf growth under nonstress conditions. Results from metabolite profiling and isotope-labeling experiments indicate that the SnRK2s are involved in organic acid and amino acid metabolism, via effects on the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, as well as on sugar metabolism. Based on previously published transcriptome data from the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant, we also identify metabolism-associated genes that are transcriptionally regulated via the SnRK2s. Together, these data suggest that maintaining ABA levels above a certain, albeit low, threshold contributes to the proper balance of plant growth and metabolism under nonstress conditions.

RESULTS

Disruption of ABA Signaling Increases Leaf Number

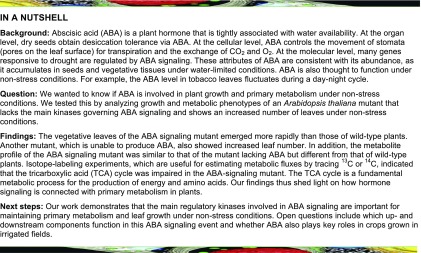

The srk2d srk2e srk2i triple knockout mutant, lacking three subclass III SnRK2s involved in ABA signaling, has more leaves than other single and double mutants and wild type (Fujita et al., 2009). To examine if the increased number of leaves in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant, under nonstress conditions, is mediated by ABA signaling, the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutants were grown on agar plates along with an ABA-biosynthesis mutant, aba2-1, and an ABA-insensitive quadruple areb mutant (areb1 areb2 abf3 abf1; Figure 1). At 12 d after germination, most srk2d srk2e srk2i plants had six to eight leaves, which was significantly greater than the four to five leaves of wild-type plants. Moreover, the number of leaves in the aba2-1 mutant was also increased compared with that in wild type, albeit to a lesser extent than that in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant. There was no significant increase in leaf number in the quadruple areb mutant. Although the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants showed an increased number of leaves to varying degrees, fresh and dry weight were higher than those of wild type only in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant. Because of its weak dormancy, srk2d srk2e srk2i showed earlier seedling establishment in terms of cotyledon greening than both the aba2-1 and areb mutants and wild type (Supplemental Figure 1). However, given that the rate of cotyledon greening in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant was equivalent to wild type within a couple of days, the earlier seedling establishment was considered to have little effect on the phenotype of 12-d-old seedlings.

Figure 1.

The Numbers of Leaves in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Triple and the aba2-1 Mutants Increase under Nonstress Conditions.

The number of leaves including visible primordia, except for cotyledons, were counted in 12-d-old seedlings.

(A) The photographs show close-ups of representative plants grown on agar plates (0.5 × MS with 1% Suc). Asterisks indicate the leaves counted. Black bars = 1 cm. WT, wild type.

(B) The graph shows the percentage of seedlings grouped by the number of leaves. One representative result of three independent experiments, each of which includes three agar plates (n = 30 seeds for each), is shown. The number of germinated seeds are presented in parentheses.

(C) Fresh and dry weights of 12-d-old seedlings. Water contents were calculated as follows: Water content = (Fresh weight − Dry weight) / Dry weight. Different letters denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) by single-factor ANOVA followed by a Tukey-Kramer posthoc test. The graphs show one representative result of two independent experiments. Bars indicate sd, n = 3. WT, wild type.

To further investigate if this phenotypic change was caused by disruption of ABA signaling, the three mutants and wild type were grown on agar plates with or without supplementary ABA. The early seedling establishment (Supplemental Figure 2), plant growth rate, leaf number, and biomass of the wild type were slightly reduced in the presence of 0.5 µM ABA (Supplemental Figure 3), whereas the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant showed the same phenotype regardless of exogenous ABA application. Meanwhile, the number of leaves in the aba2-1 mutant on agar plates supplemented with ABA was comparable to that in wild type as well as the quadruple areb mutant. However, primary root growth of the areb mutant was less inhibited by high concentrations of ABA (>100 µM) than the wild type (Yoshida et al., 2015b). Consequently, these results suggest that the increased numbers of leaves in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants are an effect of the disruption of ABA signaling, but that this effect is not principally mediated by AREB/ABF transcription factors.

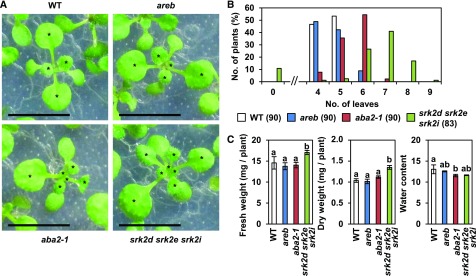

The Increased Leaf Emergence Rate in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant Is Not Because of Early Germination or Impaired Stomatal Regulation

The srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant shows pleiotropic ABA-insensitive phenotypes in various organs and cells, including seeds and guard cells (Fujii and Zhu, 2009; Fujita et al., 2009; Nakashima et al., 2009). Therefore, the increased number of leaves in the triple mutant might be a secondary consequence of other phenotypic changes. To determine whether the earlier seedling establishment has an effect on the phenotype during vegetative growth, we counted leaf numbers for two weeks after germination (Figure 2). Consistent with their germination characteristics (Supplemental Figure 1), true leaves appeared six and eight days after germination in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant and other lines, respectively (Figure 2A). Taking this difference into account, we assessed the leaf emergence rate, representing changes in leaf numbers for six days after the appearance of true leaves. The leaf emergence rate in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant was higher than those in wild type and the areb mutant but comparable to that in aba2-1 (Figure 2B). By contrast, we compared fresh and dry weights of whole seedlings on the same number of days after the appearance of true leaves and found that they were not significantly altered (Supplemental Figure 4A). We estimated the rate of plant growth by calculating the relative growth rate (Hoffmann and Poorter, 2002). The estimated relative growth rate of the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant, but not in the aba2-1 mutant, was also similar to that of wild-type (Supplemental Figure 4C). Although the projected leaf area of the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant was slightly larger than that of wild type in earlier stages, the differences were smaller in the later stages (Supplemental Figure 4D). These results imply that the number of leaves was higher in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants than the wild type regardless of their germination phenotypes. These findings were further verified by comparison with an early-germination mutant, the T-DNA knockout mutant of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3; Supplemental Figure 5; Kotak et al., 2007). Although the ABI3 T-DNA mutant, abi3 (SALK_138922), displayed early germination like the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant (Supplemental Figures 5B and 5C), its leaf emergence rate was comparable to that observed in the wild type (Figures 2C and 2D). With the exception of the early germination phenotype, other growth characteristics of the abi3 mutant were similar to wild type (Supplemental Figures 5D to 5G). Collectively, our results suggest that the early germination in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant has little effect on leaf number during vegetative growth.

Figure 2.

The srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant Shows an Increased Leaf Emergence Rate Not Because of Early Germination or impaired Stomatal Regulation.

The number of leaves including visible primordia, except for cotyledons, were counted for two weeks.

(A), (C), (E), and (G) Means of leaf numbers of seedlings grown under the same conditions as in Figure 1. Three biological replicates (n = 30 seeds for each) were examined simultaneously, and the total numbers of germinated seedlings with true leaves are shown in parentheses. Because limited numbers of seeds for complementation lines and empty vector lines were available, fewer seeds were sown (n = 16 or 25 for a replicate). CL, complementation lines (MYB60pro:SRK2E, srk2d srk2e srk2i background); EV, empty vector lines (srk2d srk2e srk2i background); WT, wild type.

(B), (D), (F), and (H) Leaf emergence rates were estimated by calculating linear regression of the plots (A), (C), (E), and (G) for 6 d after the appearance of true leaves in 90% of seedlings in a plate. The rate was independently calculated for one plate, and the bar graphs show means ± sd (n = 3). Different letters denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) by single-factor ANOVA followed by a Tukey-Kramer posthoc test. Each graph shows one representative result of three independent experiments. WT, wild type; abi3, abi3 (SALK_138922) line; CL, complementation lines (MYB60pro:SRK2E, srk2d srk2e srk2i background); EV, empty vector lines (srk2d srk2e srk2i background).

We subsequently investigated whether impaired stomatal regulation in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant could be responsible for the increased leaf number. Among the three subclass III SnRK2s, SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1 plays a predominant role in guard cells, because the srk2e/ost1 single mutant lacks stomatal regulation in response to ABA and drought (Mustilli et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002). However, unlike the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant, the srk2e mutant did not display an increased leaf number (Fujita et al., 2009). We verified this previous observation by investigating all combinations of the single, double, and triple mutants (Figures 2E and 2F). The leaf emergence rate was significantly elevated in the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant. Given that all of the mutants grew similarly to wild type in terms of biomass and total leaf area (Supplemental Figure 6), these results imply that the increased leaf number in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant is not because of its impaired stomatal regulation. To verify this conclusion, we examined whether guard cell-specific SRK2E expression is able to rescue the leaf phenotype in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant. We used the MYB60 promoter, as this well-characterized promoter is specifically expressed in guard cells (Supplemental Figure 7; Nagy et al., 2009). In two independent complementation lines, ABA-responsive stomatal closure was partially rescued (Supplemental Figure 7C). Furthermore, although AREB1 expression in response to ABA was unaltered in the complementation lines, RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION29B, a typical stress-responsive gene, was clearly induced by ABA treatment (Supplemental Figure 7D). By contrast, the leaf emergence rates in the complementation lines were the same as those in the empty vector lines (Figures 2G and 2H). Guard-cell–specific SRK2E expression also had little effect on other phenotypic traits including germination, biomass, and leaf area (Supplemental Figure 8). Together, these results suggest that the subclass III SnRK2s have negative regulatory roles in leaf emergence that are independent of their roles in maintenance of seed dormancy and stomatal closure.

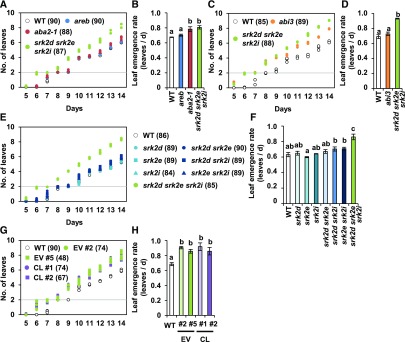

Primary Metabolite Levels Are Altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 Mutants

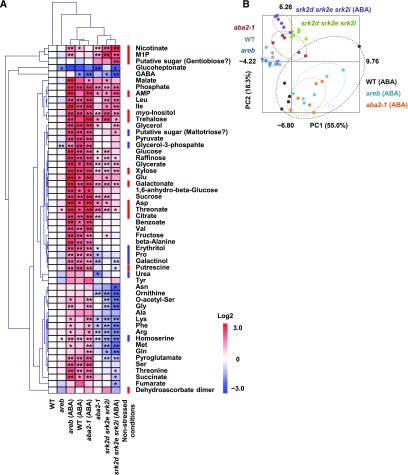

To investigate whether the growth phenotype of the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant is linked to changes in its metabolism, we analyzed metabolite profiles in the mutant, as well as those in the aba2-1 and areb mutants, by gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS; Figure 3). Chromatograms and mass spectra were evaluated using Chroma TOF 1.0 (LECO) and TagFinder 4.0 (Luedemann et al., 2008), resulting in the annotation of 54 primary metabolites. The relative amount of each primary metabolite was normalized to its level in wild type. Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the metabolite profile of the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant overlapped with that of the aba2-1 mutant, whereas the areb mutant and wild type showed similar profiles (Figure 3B). Among the 54 metabolites annotated, the levels of 20 metabolites were significantly altered in both srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 compared to wild type (Supplemental Table 1). The Asp level was increased in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants, whereas Pro and homoserine levels were reduced. Five organic acids, including citrate and threonate, highly accumulated in the two mutants, while no organic acid levels were markedly reduced. By contrast, the levels of five of the sugars and sugar alcohols were higher in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 than in wild type, whereas the levels of four of them were reduced. The metabolite profiles revealed that the SnRK2s involved in ABA signaling influence primary metabolism under nonstress conditions.

Figure 3.

The Metabolite Profiles of srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 Plants Are Different from Those of Wild-Type Plants.

Primary metabolites extracted from whole 12-d-old seedlings were analyzed by GC-MS. Chromatograms and mass spectra were evaluated using Chroma TOF 1.0 (LECO) and TagFinder 4.0 (Luedemann et al., 2008), and 54 metabolites were annotated. Three independent harvestings, each of which consists of five or six biological replicates, were concurrently subjected to GC-MS analysis.

(A) Heat map showing relative accumulation of each metabolite as compared to those in wild-type plants. For each metabolite, the value of the corresponding wild type was set to 0. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences as compared to wild type by t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Several putative sugars were tentatively annotated as “Gentiobiose” and “Maltotriose.” WT, wild type; M1P, myo-inositol-1-phosphate.

(B) PCA was performed using the Excel add-in Multibase package (Numerical Dynamics).

To further investigate whether the metabolic changes in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants were caused by disruption of ABA signaling, we analyzed metabolic profiles of seedlings grown on agar plates supplemented with ABA (Figure 4). Under this condition, in which seedling growth was slightly reduced (Supplemental Figure 3), wild-type plants had higher levels of most primary metabolites compared with those in nonstress conditions (Figure 4A). The srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant displayed insensitivity to ABA at the metabolome level (Figure 4B), paralleling the ABA insensitivity of its growth (Supplemental Figure 3). By contrast, the profiles of the aba2-1 and areb mutants were comparable to wild type when the seedlings were grown on agar plates containing ABA. Among the 13 primary metabolites that accumulated to higher levels in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants (Supplemental Table 1), nine of them, including Asp and citrate, further accumulated in the aba2-1 and areb mutants and wild type grown in the presence of ABA, two of them (nicotinate and myo-inositol-1-phosphate) accumulated to a similar level, and the levels of two of them (dehydroascorbate dimer and a putative sugar tentatively annotated as “Gentiobiose”) were unchanged (Figure 4A). The levels of seven primary metabolites that were lower in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 (Supplemental Table 1) increased in aba2-1, areb, and wild-type plants grown in the presence of ABA (Figure 4A), implying that these metabolites are regulated in an ABA-dependent manner. Interestingly, Pro and galactinol accumulate in response to dehydration stress (Urano et al., 2009). Collectively, these results suggest that the metabolic changes in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants are caused by disruption of ABA signaling, and that synthesis of several stress-responsive metabolites is impaired in the two mutants even under nonstress conditions. Given that the metabolic profile of the areb mutant was comparable to that of wild type in the presence and absence of ABA, the AREB/ABF transcription factors might be less involved in the metabolic change observed in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1.

Figure 4.

The Metabolite Profile of aba2-1 Is Comparable to That of Wild-Type Plants When Grown on Agar Plates Containing ABA.

Primary metabolites extracted from whole 12-d-old seedlings grown on agar plates with or without 0.5 μM ABA were analyzed by GC-MS as in Figure 2, and 54 metabolites were annotated. Each data point consists of five or six biological replicates.

(A) Heat map showing the relative accumulation of each metabolite compared to those in wild-type plants grown on control plates. For each metabolite, the value of wild type was set to 0. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to wild type under control conditions by t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). The 20 metabolites whose levels were significantly altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants under nonstress conditions (Supplemental Table 1) are indicated by red or blue lines, which represent increased or decreased levels compared with wild type, respectively. Several putative sugars were tentatively annotated as “Gentiobiose” and “Maltotriose.” WT, wild type; M1P, myo-inositol-1-phosphate.

(B) PCA was performed using the Excel add-in Multibase package (Numerical Dynamics). WT, wild type.

Metabolic Changes in srk2d srk2e srk2i Overlap with Those of Wild Type during Growth

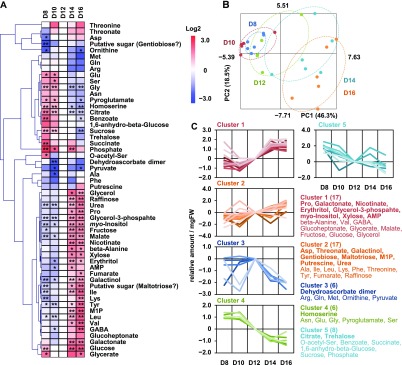

The srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants had more leaves and an altered metabolite profile under nonstress conditions compared with the wild type. Thus, subclass III SnRK2s might be involved in leaf growth either via metabolic regulation, the direct restriction of growth, or a combination of the two. To investigate whether increased leaf number in the ABA mutants is caused by the promotion of growth, we analyzed the metabolite profiles of wild-type plants at different stages of seedling growth. Along with the observed increase in the number of leaves (Supplemental Figure 9), the metabolite profiles displayed considerable alterations (Figure 5). Primary metabolites were classified by k-means clustering based on the chronological changes they exhibited during seedling growth (Figure 5C). Among the five clusters, clusters 1 and 2 contained the metabolites that accumulated during seedling growth, while clusters 3, 4 and 5 included the metabolites whose levels decreased over this period. We postulated that if the altered metabolite profiles in the 12-day-old srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 seedlings are caused by the direct promotion of growth, the profile should overlap with those of 14- and 16-d-old wild-type seedlings compared to that of 12-d-old wild type. Based on the relative levels in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 compared to that of wild type (Figure 3), the primary metabolites were further classified into four groups (Table 1). The primary metabolites whose levels increased in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1, such as Asp and myo-inositol, also increased during wild-type growth, whereas the level of homoserine decreased in both mutants and in wild-type seedlings during growth. Thus, these metabolites showed the same trend in the ABA mutants and wild type during growth and are likely to be associated with growth promotion rather than ABA signaling. On the other hand, the primary metabolites whose levels decreased in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1, such as Pro and galactinol, increased during wild-type growth. Likewise, the levels of citrate and trehalose, which increased in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1, decreased during wild-type growth. Thus, these metabolites showed the opposite trend in the ABA mutants and wild type during growth and are likely associated with ABA signaling rather than growth promotion.

Figure 5.

Metabolite Profiles Are Altered during Seedling Development.

Primary metabolites extracted from whole 8-, 10-, 12-, 14-, and 16-d-old wild-type seedlings (Col-0) were analyzed by GC-MS as in Figure 2, and 54 metabolites were annotated. Each data point consists of five or six biological replicates.

(A) Heat map showing relative accumulation of each metabolite as compared to those in 12-d-old seedlings. For each metabolite, the value of 12-d-old seedlings was set to 0. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to 12-d-old seedlings by t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Several putative sugars were tentatively annotated as “Gentiobiose” and “Maltotriose.” M1P, myo-inositol-1-phosphate.

(B) PCA was performed using the Excel add-in Multibase package (Numerical Dynamics).

(C) Primary metabolites were classified by k-means clustering based on their chronological changes. Number of clusters, k (≈√N/2 = 5.20), was determined according to the crude rule of thumb (Mardia et al., 1979). The number of metabolites in each cluster is shown in parentheses, and the 20 primary metabolites, which were significantly altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants (Supplemental Table 1), are indicated by boldface. FW, fresh weight.

Table 1. Primary Metabolites with Significantly Altered Levels in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 Mutants Classified by their Chronological Changes in Wild Type.

| srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 | Wild-type seedling | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | Decreased | ||||

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | |

| Increased | Galactonate | Asp | Dehydroascorbate dimer | n/a | Citrate |

| Nicotinate | Threonate | Trehalose | |||

| myo-Inositol | Gentiobiose | ||||

| Xyl | M1P | ||||

| AMP | Putrescine | ||||

| Decreased | Pro | Galactinol | n/a | Homoserine | n/a |

| Erythritol | Maltotriose | ||||

| Glycerol-3-phosphate | Urea | ||||

Primary metabolites were classified by k-means clustering based on their chronological changes during seedling growth (Figure 5C), and 20 metabolites, the levels of which were significantly altered in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 are listed. Except for dehydroascorbate dimer, citrate, trehalose, and homoserine, no metabolites were in these groups of clusters 3, 4, and 5 as indicated by blank spaces. M1P, myo-Inositol-1-phosphate; n/a, not applicable.

The srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant Shows Altered Relative Rates through the Major Pathways of Carbohydrate Oxidation

Our metabolome analyses suggested that subclass III SnRK2s regulate plant metabolism both directly and indirectly via secondary effects after growth restriction. To obtain further insights into metabolic fluxes in srk2d srk2e srk2i, we performed radio-isotope labeling experiments using 14C-Glc (Figure 6). Given that srk2d srk2e srk2i plants do not grow well at the ambient humidity of standard laboratory growth conditions and show an early-flowering phenotype (Fujita et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013), we performed isotope-labeling experiments on srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild-type plants grown under high relative-humidity (RH) conditions, with a short photoperiod (8 h) to suppress flowering. Wild type was also grown under standard RH conditions as an additional control. Respiratory activity was analyzed by supplying positionally labeled 14C-Glc and monitoring the evolution of 14CO2. Leaf discs derived from 5-week-old plants were incubated with [1-14C]- or [3:4-14C]-Glc (1 mM with specific activity of 2.8 GBq mol−1) for 4 h in the light, and the evolved 14CO2 was collected at 1-h intervals (Figure 6A). The 14CO2 emissions derived from [3:4-14C]- and [1-14C]-Glc were used to estimate relative fluxes through the TCA cycle and other respiratory pathways (i.e. glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, respectively). Compared with control wild-type plants grown under standard RH conditions, srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild type grown under high RH conditions showed higher 14CO2 emissions from both substrates. The srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant showed emissions from [1-14C]-Glc comparable to the wild type, whereas the emissions from [3:4-14C]-Glc were slightly, but significantly, higher in srk2d srk2e srk2i after 3 h. Consistently, srk2d srk2e srk2i showed a higher ratio of the TCA cycle to other respiratory pathways (C3-4:C1) than wild type grown under high RH conditions, suggesting that the flux through the TCA cycle in srk2d srk2e srk2i is increased.

Figure 6.

14C-Glc Metabolism Is Altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant.

Leaf discs were derived from 5-week-old plants grown under control conditions or high RH conditions.

(A) The leaf discs were incubated in 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.5) supplemented with [1-14C]- or [3:4-14C]-Glc. The 14CO2 liberated was captured in a NaOH trap every hour, and the amount of radiolabel released was subsequently quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Each point represents mean ± sd (n = 4). *P < 0.05 (t test). FW, fresh weight; WT, wild type.

(B) to (E) Leaf discs were incubated in 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.5) supplemented with [U-14C]-Glc for 4 h. Each sample was extracted with ethanol, and amount of radioactivity in each metabolic fraction was determined as described in Methods. Label incorporated (B), redistribution of radiolabel (C), specific activity of hexose phosphates (D), and estimated metabolic flux (E) are presented as mean ± sd (n = 5 or 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (t test). FW, fresh weight; WT, wild type.

To further dissect metabolic fluxes in carbon metabolism in srk2d srk2e srk2i, we also performed [U-14C]-Glc labeling. Leaf discs derived from 5-week-old plants were incubated with [U-14C]-Glc (1 mM with specific activity of 7.0 GBq mol−1) for 4 h in the light. In addition to monitoring 14CO2 emissions, we determined the distribution of 14C in major cellular components (amino acids, organic acids, sugars, protein, starch, and the cell wall). In the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant, significantly higher amounts of label were both taken up and metabolized compared to wild type (Figure 6B). The proportions of label in amino acids, hexose phosphates, and Suc were lower in srk2d srk2e srk2i than in wild type grown under high RH conditions, whereas labeling of starch and the cell wall was increased (Figure 6C). We then determined the specific activities of the hexose phosphate pools in srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild-type plants (Figure 6D) and used these values to estimate the approximate fluxes into respiration, Suc, protein, starch, and cell wall following the approach described in Geigenberger et al. (1997); Figure 6E). The estimated metabolic flux into each fraction, especially into protein, starch, and the cell wall, was increased in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant. Given that the TCA cycle is a key source of C-skeletons for amino acid synthesis, higher activity of the TCA cycle in srk2d srk2e srk2i might conceivably lead to a higher relative flux into amino acids and potentially protein; however, the enhanced approximate flux to starch and the cell wall is more difficult to explain. Increased accumulation of starch might be expected if growth were restricted and the plants had more carbon than they needed for growth. However, given that there was also an increase in cell wall synthesis, this scenario seems unlikely.

Radio-labeling approaches provide a broad overview of metabolic fluxes into major cellular components, but resolution to the single metabolite level is technically challenging and time-consuming. Therefore, we also performed stable-isotope labeling experiments with [U-13C]-Glc to investigate the metabolic alterations in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant in more detail (Figure 7). Leaves were detached from 5-week-old plants grown under the same high RH conditions as for the 14C-Glc labeling, and [U-13C]-Glc was fed via the petioles for 1 to 2 h, before the quenching of metabolism and subsequent analysis of isotopomers by GC-MS. Figure 7 shows total isotope accumulation in 22 primary metabolites calculated by multiplying the enrichment of 13C (after subtraction of natural abundance) by the amount of the metabolite (Supplemental Figures 10 and 11). There was no significant change in the Glc content of the plants supplied with [U-13C]-Glc (Supplemental Figures 10 and 11), suggesting that there was no major perturbation of metabolism from Glc feeding. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that uptake of exogenous Glc affected Glc signaling, it seems likely that any effects of this kind would occur in both the mutant and wild-type control plants. Thus, any differences in the distribution of 13C-label in the mutant and wild-type plants should reflect the inherent metabolic differences between the genotypes. Compared with wild type grown under high RH conditions, the accumulation of label in several amino acids, such as Ala, Asp, 4-aminobutyric acid (GABA), Phe, Ser, and Val, was higher in srk2d srk2e srk2i, whereas that in Gln was lower. Among the TCA cycle intermediates, citrate was labeled to a greater extent in srk2d srk2e srk2i than in wild type, whereas fumarate was more highly labeled in the wild type than in the mutant. The higher amount of label in citrate is because of the accumulation of this metabolite over the time course of the experiment (Supplemental Figure 11), whereas the lower amount of label in fumarate is because of less incorporation of 13C into fumarate, as the overall pool size was unchanged (Supplemental Figure 10). There were no significant differences between mutant and wild type in the labeling or pool sizes of succinate and malate. These results indicate that there was not a uniform change in flux through the TCA cycle, but more specific changes in the fluxes into and/or out of citrate were detected. Interestingly, there was little or no incorporation of 13C into Fru in srk2d srk2e srk2i during the 2-h feeding (Supplemental Figure 10), whereas Fru was labeled in the wild-type controls.

Figure 7.

Label Accumulation After 13C-Glc Feeding Is Altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant.

The leaves of Arabidopsis plants grown in soil for five weeks under control or high RH conditions were fed via the petiole with 15 mM [U-13C]-Glc by incubation in 10 mM MES-KOH (pH 6.5) for 2 h. Total 13C accumulation was obtained by multiplying the enrichment of 13C by the amount of metabolite. Data presented are mean ± sd (n = 5 or 6). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild type grown under high RH. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (t test). DW, dry weight; nd, no data available; WT, wild type.

Diurnal Changes in Organic Acids and Other Metabolic Intermediates in srk2d srk2e srk2i

The data from the labeling experiments and GC-MS metabolite analysis pointed toward altered fluxes through the respiratory pathways in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants. To investigate this further, we used anion-exchange liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; Lunn et al., 2006) to determine the absolute amounts of organic acids and phosphorylated intermediates from central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis and the TCA cycle (Figure 8). Furthermore, to gain a more complete overview of metabolism during the diurnal light-dark cycle, we collected whole 12-d-old seedlings grown under a 16-h photoperiod on agar plates at the end of night (EN), the middle of day (MD), and the end of day (ED) for analysis. There was a broad agreement between the GC-MS (Figures 3 to 5) and LC-MS/MS (Figure 8) data for those metabolites that were measured by both techniques. For example, the levels of phosphoenolpyruvate, citrate, aconitate, isocitrate, and 3-phosphoglycerate were higher in both srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 than in wild-type plants at one or more of the sampling times. In addition, the LC-MS/MS analysis showed that the amounts of aconitate and isocitrate (not measured by GC-MS) at EN were significantly higher in the mutants than in wild type. Intriguingly, the level of an unknown compound with the same parent ion m/z as glycerate, but eluting before glycerate, significantly increased throughout the day in both mutants. On the other hand, the amounts of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, glucose 1-phosphate, sucrose-6F-phosphate, galactose 1-phosphate, and glycerol-3-phosphate were markedly reduced in srk2d srk2e srk2i at EN or MD, or both, but not in aba2-1. Together, these data show that srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 both have higher citrate, aconitate, and isocitrate levels than wild-type plants, but the decreases in some sugar phosphates were observed only in srk2d srk2e srk2i.

Figure 8.

Diurnal Changes in Organic Acids and Metabolic Intermediates in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant.

Organic acids and phosphorylated intermediates extracted from whole 12-d-old seedlings at EN, MD, and ED under long-day conditions (16-h light and 8-h dark) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. Extraction and quantification were performed as described in Lunn et al. (2006). Because of significant changes in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants, a metabolite with the same parent ion m/z as glycerate, but eluting before glycerate, is shown as an unknown compound. Each point represents mean ± sd (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (t test, compared to wild type at the same time point). 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; ADPGlc, ADPglucose; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; Fru6P, fructose 6-phosphate; FW, fresh weight; G1,6BP, glucose-1,6-bisphosphate; Gal1P, galactose 1-phosphate; Glc1P, glucose 1-phosphate; Glc6P, glucose 6-phosphate; Gly3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; Man6P, mannose 6-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; Suc6P, sucrose-6F-phosphate; UDPGlc, UDPglucose; WT, wild type.

Expression of Metabolism-Associated Genes Is Altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i Mutant

We also used transcriptome data to evaluate the cause of the metabolic changes observed in srk2d srk2e srk2i. For this purpose, we reanalyzed previously reported microarray data obtained from samples in which srk2d srk2e srk2i was grown under control conditions for 12 d (Fujita et al., 2009). In addition, we performed microarray analysis of the aba2-1 mutant grown under identical conditions and processed the data in the same way as that of srk2d srk2e srk2i. Compared with wild type, the expression of 2,627 and 4,649 genes was significantly (P < 0.05) altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants, respectively (Supplemental Figure 12A). Among these, 432 and 822 genes linked to metabolism were annotated using the ARACYC 14.0 database (www.plantcyc.org/databases/aracyc/14.0). The genes that are up- or down-regulated in common in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 are listed in Supplemental Data Set 1. The expression data were also mapped onto diagrams of specific metabolic pathways or processes to identify any coordinated changes in expression of metabolically related genes (Supplemental Figures 13 to 18). Among genes in the Suc degradation pathway, SUCROSE SYNTHASE4 expression decreased in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1, whereas HEXOKINASE3 expression increased in both mutants (Supplemental Figure 13A). Suc and Fru levels were not markedly altered in srk2d srk2e srk2i or aba2-1 (Figure 3), whereas the rate of carbon flux into Fru was seemingly impaired in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant after 13C-Glc feeding (Figure 7; Supplemental Figures 10 and 11). Thus, transcriptional regulation of SUCROSE SYNTHASE4 and HEXOKINASE3 might be involved in Suc catabolism via Fru. Given that several sugar transporter genes were transcriptionally altered in the mutants (Supplemental Figure 14), the movement of Suc into compartments, such as vacuoles where it would be accessible to vacuolar invertases, might also account for the changes in Suc and hexose levels. Several genes associated with starch degradation were down-regulated in the aba2-1 mutant but showed little or no change in expression in srk2d srk2e srk2i (Supplemental Figure 13B). A GALACTINOL SYNTHASE gene, GolS1, encoding a regulatory enzyme involved in raffinose synthesis, was repressed in both mutants (Supplemental Figure 13C). Although GolS1 was suggested to be involved in ABA-independent raffinose synthesis in response to dehydration (Urano et al., 2009), the expression of GolS1 and its homolog, GolS2, was clearly reduced in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants (Supplemental Figure 12B). Interestingly, MYOINOSITOL OXYGENASE1 was also repressed in both mutants (Supplemental Figure 13D). Reduced expression of GolS1 and MYOINOSITOL OXYGENASE1 likely explains the decreased levels of raffinose and increased levels of myo-inositol in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 (Figure 3). The expression of the genes for the TCA cycle enzymes was mostly unaffected in srk2d srk2e srk2i, but the expression of FUMARASE2 (FUM2) encoding a cytosolic isoform of fumarase, was reduced in both mutants (Supplemental Figures 12B and 15). The expression of the genes for gluconeogenic enzymes was mostly unaffected in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1, with the exception of NADP-dependent malic enzyme2 and CP12-2, which increased and decreased, respectively (Supplemental Figure 16). Although Asp, Pro, and homoserine levels were significantly altered in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 (Figure 3), the expression of genes for amino acid metabolism was only slightly altered in the mutants (Supplemental Figure 17).

As trehalose was highly accumulated in both mutants (Figure 3), we analyzed the expression of genes associated with trehalose metabolism. Trehalose is synthesized in a two-step pathway catalyzed by trehalose 6-phosphate synthase (TPS) and trehalose 6-phosphate (Tre6P) phosphatase and hydrolyzed by trehalase. There was no change in expression of the class I TPS genes (TPS1-TPS4) encoding the only catalytically active TPS enzymes, no consistent trend for the Tre6P phosphatase genes, and no change in TREHALASE1 (TRE1) expression (Supplemental Figure 18). However, further analysis of selected genes by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), which is more quantitative for low abundance transcripts than microarray analysis, showed that TRE1 expression was significantly reduced in srk2d srk2e srk2i in both the presence and absence of exogenous ABA (Supplemental Figure 12B). However, given that the reduction of TRE1 expression in the aba2-1 mutant was not statistically significant (P > 0.05), these results imply that ABA signaling via subclass III SnRK2s is partially involved in the transcriptional regulation of TRE1. Taken together, these data suggest that transcriptional regulation by subclass III SnRK2s is important for several metabolic pathways, such as raffinose synthesis and the TCA cycle, and therefore plays a role in the maintenance of primary metabolism under nonstress growth conditions.

DISCUSSION

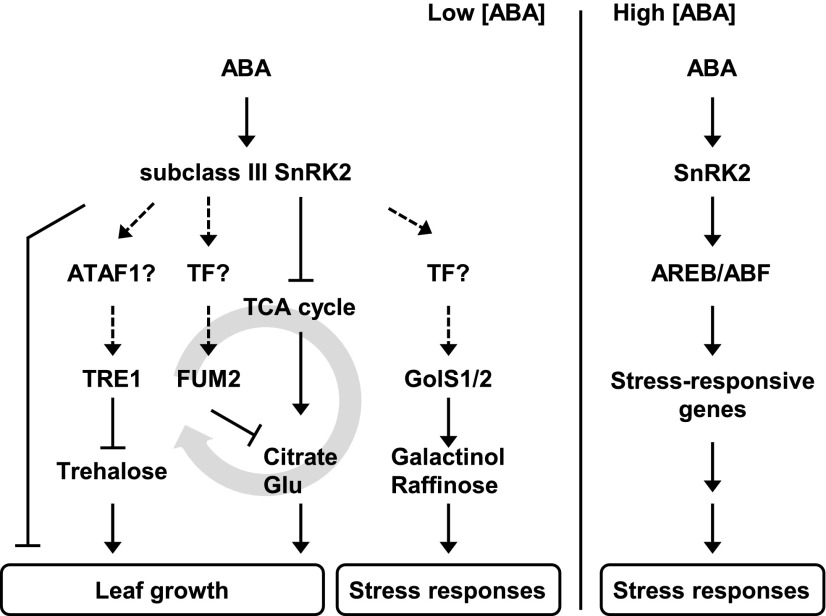

ABA is a pivotal hormone in plant responses to osmotic stress, playing a key role in adapting metabolism and gene expression, at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels, to help the plant cope with stress conditions (Cutler et al., 2010; Yoshida et al., 2015a). Here, we report that ABA signaling mediated by subclass III SnRK2s also has a role in the maintenance of metabolism and leaf growth under nonstress conditions. The srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant displayed an increased number of leaves, a higher leaf emergence rate, and altered metabolic profiles under nonstress conditions compared with wild type. The ABA-deficient aba2-1 mutant showed similar morphological and metabolic phenotypes to srk2d srk2e srk2i, but these disappeared when aba2-1 was grown on agar plates supplemented with ABA. These results suggest that normal leaf growth and metabolism under nonstress conditions are maintained by ABA biosynthesis and signaling via ABA2 and subclass III SnRK2s. Consistent with this idea, it has been demonstrated that subclass III SnRK2s are present irrespective of the presence of stress (Fujita et al., 2009), and that lack of ABA2 decreases ABA contents to 20% of wild type under control conditions (Léon-Kloosterziel et al., 1996; González-Guzmán et al., 2002). Moreover, our isotope-labeling experiments using radio- and stable-isotope labeled Glc revealed that the lack of SnRK2s enhances respiration via the TCA cycle. Comparison of the metabolite profiles in srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild-type plants during growth also suggested that the SnRK2s are involved in regulating primary metabolism both directly and indirectly via the restriction of leaf growth. Taken together, despite the importance of subclass III SnRK2-mediated ABA signaling in response to osmotic stresses, it is clear that the SnRK2s play key roles in ABA signaling responsible for maintaining normal metabolism and leaf growth under nonstress conditions (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Proposed Model of the Role of Subclass III SnRK2s in ABA-Mediated Signaling during Primary Metabolism and Leaf Growth.

Under normal conditions (in which ABA levels fluctuate but remain relatively low), subclass III SnRK2s mediate the activity of the TCA cycle, which is related to citrate and Glu levels, partially through transcriptional regulation of FUM2. Trehalose metabolism is mediated through TRE1 expression. In addition, the SnRK2s mediate leaf growth indirectly of these types of metabolic regulation. Even under normal conditions, some amounts of galactinol and raffinose are synthesized via GolS1 and GolS2, which are transcriptionally regulated by the SnRK2s. The key transcription factors under osmotic stress conditions, including AREB/ABFs, are not involved in the regulation of metabolism and growth. Dashed arrows indicate transcriptional regulation in need of further validation. TF, transcription factor.

Carbon Metabolism Is Regulated By the SnRK2 Kinases

Our isotope-labeling experiments revealed that respiration through the TCA cycle is enhanced in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant (Figure 6). Stable-isotope labeling with [U-13C]-Glc provided greater resolution at the individual metabolite level, revealing greater incorporation of label into citrate in srk2d srk2e srk2i compared with wild type, but no significant differences between genotypes in the labeling of succinate and malate (Figure 7). In addition, citrate, aconitate, and isocitrate were highly accumulated in srk2d srk2e srk2i, whereas the amounts of other intermediates were unchanged (Figures 3 and 8). These results are consistent with previous reports that the TCA cycle can operate in noncyclic flux modes in illuminated leaves (Tcherkez et al., 2009; Sweetlove et al., 2010). Given that pyruvate dehydrogenase is inhibited in the light (Tcherkez et al., 2005), a noncyclic flux runs from oxaloacetate via malate, pyruvate, and acetyl CoA to citrate. Following this proposed model, our results suggest that noncyclic fluxes in the TCA cycle are enhanced in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant. Given that the purpose of mitochondrial oxidation of malate is to produce citrate, which is converted to 2-oxoglutarate as the precursor for Glu and Gln in photosynthetic nitrate assimilation (Hanning and Heldt, 1993), the increased amount of Glu in aba2-1 (Figure 3) is consistent with this model. However, it is also conceivable that the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutations somehow alleviate light-induced inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase, thus allowing pyruvate to feed into citrate. Indeed, such a process occurs in plants containing high levels of Tre6P (Figueroa et al., 2016). That said, further studies will be required to address the exact mechanisms underlying the increased flux toward citrate in these plants. Given that citrate showed the opposite trend in the ABA mutants and wild type during seedling growth (Figure 5; Table 1), ABA signaling mediated by subclass III SnRK2s appears to directly regulate these noncyclic fluxes in the TCA cycle in the light (Figure 9).

Interestingly, citrate levels are higher in the fum2-1 mutant than wild type when grown in the light (Pracharoenwattana et al., 2010). FUM2 is a cytosolic fumarase that produces fumarate from malate during the day, and increased amounts of fumarate are thought to represent an alternative carbon sink (besides starch) in Arabidopsis leaves. Given that FUM2 expression was reduced in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 (Supplemental Figure 12), the impaired conversion between malate and fumarate in the cytosol in the light might enhance the flux from malate to citrate. However, this is difficult to experimentally verify because of the complex compartmentalization of these organic acids in plants (Szecowka et al., 2013). That said, a recent study of various Arabidopsis accessions also revealed that an insertion/deletion polymorphism in the FUM2 promoter, which is linked to the mRNA abundance of FUM2, is associated with malate and fumarate levels, the fumarate/malate ratio, and the dry weight of seedlings (Riewe et al., 2016). Our metabolome and transcriptome data for the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant raised the possibility that FUM2 expression is under the control of subclass III SnRK2s; the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of FUM2 should be addressed to provide a better understanding of the role of the TCA cycle in plant growth. Our qRT-PCR analyses provided an insight into how FUM2 is transcriptionally regulated. Because FUM2 is less highly induced by exogenous ABA in srk2d srk2e srk2i and areb than in wild type (Supplemental Figure 12), FUM2 expression in response to ABA might be regulated by the SnRK2-AREB/ABF signaling pathway. Intriguingly, FUM2 was recently shown to be essential for acclimation to low temperature, as the fum2 mutant is unable to modify its photosynthetic rate in response to the cold (Dyson et al., 2016). This is interesting in light of this study because of the similarities in the regulation of the responses to cold and osmotic stress and the finding that ABA is involved in both processes (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005). The authors postulate that cytosolic fumarate may be a signal that allows the buffering of photosynthesis in a manner fitting the prevailing conditions, potentially in a manner consistent with the operation of the oxaloacetate-malate shunt (Foyer et al., 1990).

Our observations are also consistent with the findings of several studies in which each enzyme of the mitochondrial TCA cycle was down-regulated and the consequences on photosynthesis and growth investigated (reviewed in Nunes-Nesi et al., 2011, 2013). Three of these enzymes, mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2005), mitochondrial fumarase (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2007), and succinate dehydrogenase (Araújo et al., 2011), are of particular interest in this regard. Decreased expression of mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase resulted in an increase in photosynthesis and plant growth via a mechanism apparently mediated by ascorbate (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2005). By contrast, manipulating the activities of mitochondrial fumarase or succinate dehydrogenase resulted in inhibited and enhanced rates of photosynthesis and growth, respectively, via reciprocal changes in malate and fumarate levels, with opposite effects on stomatal conductance (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2007; Araújo et al., 2011). Together, these findings provide strong support for our contention that the growth effect is mediated by an effect on the TCA cycle resulting directly from the alteration in FUM2 expression. This process most likely operates by an as yet unknown mechanism linking ABA regulation and growth via effects on the rate of respiration.

In addition to the effects on citrate metabolism, trehalose metabolism might also be directly regulated by subclass III SnRK2s (Table 1). In vascular plants, Tre6P, the phosphorylated intermediate of trehalose biosynthesis, plays an important role as a Suc-signaling metabolite during plant growth and development, and trehalose could also function as a signal metabolite, especially under biotic and abiotic stress conditions (Fernandez et al., 2010; Lunn et al., 2014). Despite the increased trehalose levels in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant, our LC-MS/MS analysis showed that Tre6P levels in srk2d srk2e srk2i were comparable to those in wild type (Figure 8). This finding, together with the gene expression data (Supplemental Figures 12 and 18), suggest that reduced TRE1 expression under control conditions may lead to increased trehalose accumulation in srk2d srk2e srk2i, as observed in the trehalase-deficient tre1 mutant (Van Houtte et al., 2013). TRE1 is transcriptionally regulated by ABA signaling and is involved in stomatal regulation in response to ABA (Van Houtte et al., 2013). Although subclass III SnRK2s and four AREB/ABFs are key positive regulators of ABA-responsive genes, ABA-induced TRE1 expression was not markedly impaired in srk2d srk2e srk2i or areb (Supplemental Figure 12), implying that subclass III SnRK2s are only conditionally involved in the transcriptional regulation of TRE1. TRE1 is directly regulated by the ATAF1/ANAC002 transcription factor, which plays key roles in carbon starvation responses (Garapati et al., 2015). Interestingly, a group of stress-responsive NAC transcription factors, including ATAF1/ANAC002, is transcriptionally regulated downstream of the SnRK2s and mediates ABA-inducible leaf senescence (Takasaki et al., 2015). The interaction between ABA signaling and trehalose metabolism has been reported (Avonce et al., 2004; Ramon et al., 2007; Vandesteene et al., 2012); however, further studies are needed to investigate how endogenous trehalose levels affect plant growth and metabolism.

SnRK2s Play Different Roles in Primary Metabolism under Stress and Nonstress Conditions

Among the 20 primary metabolites whose levels were significantly altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants, Pro, citrate, galactinol, and Xyl levels have been shown to increase in response to dehydration (Urano et al., 2009). Galactinol and its product, raffinose, metabolism are thought to be regulated independently of ABA biosynthesis via NINE-CIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE3 (Urano et al., 2009). However, Pro and galactinol were present at low levels in srk2d srk2e srk2i but at high levels in seedlings grown on agar plates containing ABA (Figures 3 and 4). These results suggest that the levels of these metabolites are positively regulated by ABA signaling mediated by the SnRK2s. The reduced expression of GolS1 and GolS2 in srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 (Supplemental Figure 12) also supports the notion that subclass III SnRK2s are involved in galactinol and raffinose synthesis. By contrast, the levels of most dehydration-induced amino acids and organic acids (Urano et al., 2009) were not significantly altered in srk2d srk2e srk2i or aba2-1. These findings suggest that some stress-responsive metabolic activity is regulated by subclass III SnRK2 even under normal conditions, and that primary metabolism controlled by the SnRK2s is related to normal growth rather than stress responses.

Consistent with the above, four AREB/ABF transcription factors, which play key roles in plants under drought-stress conditions, might not be involved in metabolic regulation under nonstress conditions. AREB1/ABF2, AREB2/ABF4, ABF3, and ABF1, the best characterized substrates of subclass III SnRK2s, regulate most downstream genes of the SnRK2s in response to ABA and osmotic stress (Fujita et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 2010, 2015b). Fewer genes are down-regulated in the areb1 areb2 abf3 mutant compared with those of wild type in the absence of stress treatment (Yoshida et al., 2010). Moreover, the AREB/ABFs are transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally regulated by ABA signaling under osmotic stress conditions (Fujita et al., 2005; Yoshida et al., 2010). Thus, the four AREB/ABFs are thought to be fully functional in osmotic stress responses. In agreement with this notion, the areb mutant was more similar to wild type than the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant in terms of growth and metabolic characteristics under nonstress conditions (Figures 1 to 3), suggesting that the four AREB/ABFs are not involved in the aspects of primary metabolism mediated by subclass III SnRK2s (Figure 9). Currently, little is known about the transcription factors that function downstream of the SnRK2s, except for the AREB/ABFs, and little attention has been paid to the transcriptional regulation of primary metabolism under nonstress conditions. Further studies focusing on the candidate metabolism-associated genes, such as FUM2 and TRE1, will aid in understanding how primary metabolism under nonstress conditions is transcriptionally regulated.

To minimize the secondary effects caused by the impaired stomatal regulation in the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant, we performed the experiments using plant material grown on standard growth medium or under high RH conditions. However, because the stomata of aba2-1 grown on standard agar medium are more likely to be open than those of wild type (Christmann et al., 2007), there might also have been differences in stomatal aperture between srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild-type plants under the nonstress growth conditions used in our study. Thus, the impaired stomatal regulation in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant might have subtle effects on the changes in leaf numbers, metabolite profile, and estimated relative metabolic flux. To assess this possibility, we studied a series of mutants that also show impaired stomatal regulation, including the srk2e single mutant, and complementation lines that showed partially rescued stomatal responses (Figure 2). Our data measuring the chronology of leaf numbers suggested that the secondary physiological changes in the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant, including impaired stomatal closure, are not directly associated with the increased leaf number. Furthermore, reassimilation of released 14CO2 is negligible in the experimental system used for the isotope labeling (Harrison and Kruger, 2008). Thus, the potential change in respiration ratio because of impaired stomatal closure in srk2d srk2e srk2i likely had little effect on our estimates of metabolic flux (Figure 6).

On the other hand, in some cases, such as the 14CO2 emission derived from [1-14C]-Glc, the changes between wild type under different RH conditions were greater than those between srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild type under high RH conditions (Figures 6 and 7). These results imply that the metabolism of wild-type plants is adjusted when grown under high RH conditions, possibly because of the change in transpiration rate. Thus, our results could be validated by fully distinguishing the direct effects caused by the disruption of ABA signaling from the secondary effects. We generated complementation lines of srk2d srk2e srk2i expressing SRK2E in guard cells under the control of the MYB60 promoter. However, the impaired stomatal response to ABA was not fully rescued (Supplemental Figure 7), suggesting these plants have an altered transpiration rate under standard RH conditions. This unexpected result could be partially explained by transcriptome data showing that MYB60 is more specifically expressed in guard cells but less abundant than SRK2E (Yang et al., 2008). Analyses of the mutants and/or transgenics of ABA metabolism, signaling, and transport, which have a comparable transpiration rate to wild type, might confirm and extend our findings. Collectively, our data suggest that the SnRK2s play a role in maintaining leaf growth and primary metabolism under nonstress conditions, in addition to their roles in regulating seed maturation, stomatal closure, and stress-responsive gene expression.

Leaf Growth Is Maintained By ABA Signaling Via the SnRK2s

Leaves are initiated in the shoot apical meristem in a regular spatial and temporal pattern. Leaf number can be affected by differences in leaf initiation rate and the duration of the vegetative phase before the floral transition. In addition to considerable changes in its metabolite profile, the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant displayed an increased leaf number under control conditions (Figures 1 and 2), and our analyses of the abi3 mutant suggested that the increased leaf emergence rate is not because of the earlier seedling establishment. The growth of srk2d srk2e srk2i and abi3 mutants and wild type was similar (Supplemental Figure 5), implying that the overall growth related to biomass was not promoted by the mutation in the SnRK2s. Rather, this promotion of growth in terms of leaf number in srk2d srk2e srk2i might be caused by increased activity of the TCA cycle and enhanced relative metabolic fluxes into protein, starch, and cell wall components (Figure 6). The difference between the metabolite profiles of srk2d srk2e srk2i and wild-type plants during seedling growth also suggested that subclass III SnRK2s are involved in regulating leaf growth (Figure 5; Table 1). Several studies have explored the relationship between primary metabolism and leaf growth at the molecular level (Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013). Leaf number in Arabidopsis is affected by the duration of the vegetative phase, which can be divided into the juvenile and adult phases. In the juvenile-to-adult phase transition, microRNA156 (miR156) plays a crucial role in maintaining the juvenile phase by suppressing several SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) transcription factor genes involved in regulating leaf shape or flowering (Huijser and Schmid, 2011). The miR156-SPL module plays key roles in the adaptation to recurring heat stress as well as developmental processes (Stief et al., 2014). Sugars repress miR156 abundance transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally during the phase transition, suggesting that sugar metabolism is associated with developmental timing (Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013). In contrast with several sugars and sugar alcohols, such as trehalose, galactinol, and myo-inositol, the major soluble sugar (Glc, Fru, and Suc) contents were not significantly altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i mutant at the whole seedling level (Figure 3), except for the reduced incorporation of 13C-Glc into Fru (Figure 7). However, because several genes for sugar metabolism and transport were transcriptionally altered in the srk2d srk2e srk2i and aba2-1 mutants (Supplemental Figures 13A and 14), the rates of sugar metabolism, including biosynthesis, degradation, and transport, may be altered in the mutants. Further studies focusing on specific tissues, such as the shoot apical meristem, are clearly required to confirm if subclass III SnRK2s regulate miR156 and SPLs during the juvenile-to-adult phase transition through sugar metabolism.

Our data shed light on the role of ABA in maintaining metabolism and growth under nonstress conditions. ABA is thought to have been acquired after the origin of terrestrial plants. This idea is supported by the finding that the key genes in ABA signaling, including genes for PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors, PP2C phosphatases, and SnRK2 kinases, are evolutionarily conserved from mosses to angiosperms (Umezawa et al., 2010). In addition to their roles in angiosperms under osmotic stress conditions, ABA and an ortholog of the ABI3 transcription factor are essential for desiccation tolerance in the moss Physcomitrella patens (Khandelwal et al., 2010). In addition, disruption of PpABI1A, an ortholog of Arabidopsis PP2Cs, enhanced the formation of specialized reproductive brood cells in response to ABA (Komatsu et al., 2009). We therefore propose that terrestrial plants may use ABA as a signaling molecule to adjust their metabolism and growth both in response to stress conditions and under growth conditions under which no stress is apparent.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Col-0 ecotype was used as the wild type. Generation of the srk2d srk2e srk2i and areb1 areb2 abf3 abf1 mutants was described in Fujita et al. (2009) and Yoshida et al. (2015b). The aba2-1 mutant (CS156; Col background) and the T-DNA mutant of ABI3 (SALK_138922) were provided by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre, respectively. Seeds were sown on half-strength Murashige & Skoog (0.5 MS) agar plates supplemented with 1% Suc and kept in the dark at 4°C for 3 d for stratification. Plants were grown at 22°C under long-day conditions (16-h light and 8-h dark) of 100 μmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density (Osram fluorescent lamps L18W/840) unless otherwise noted. For ABA treatment, plants were grown on 0.5 MS agar plates containing 1% Suc with or without 0.5 μM (±)-ABA (Sigma-Aldrich). For isotope-labeling experiments, plants were grown on 0.5 MS agar plates with 1% Suc at 22°C under long-day conditions for one week and then transferred to soil. Transferred plants were grown in soil under short-day conditions (8-h light and 16-h dark) of 100 μmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density (Osram fluorescent lamps L36W/830 and L36W/840) for 4 weeks. During the four-week period, all plants were grown under transparent plastic covers for the first week, and then grown under control relative humidity (RH) conditions without covers (22.0 ± 0.5°C, 52.0 ± 1.2%RH) or high RH conditions with covers (21.1 ± 0.4°C, 77.6 ± 4.5%RH) for another three weeks.

Plasmid Construction

The Gateway compatible plant transformation vector harboring the MYB60 promoter (Nagy et al., 2009) was used to generate the MYB60pro:SRK2E plasmid construct. The entire 1.1-kb coding region of SRK2E was amplified by PCR using AscI-PacI linker primers (Supplemental Table 2). The PCR product was then digested with AscI and PacI and cloned into the AscI and PacI sites of the vector, producing MYB60pro:SRK2E. The vector was also digested with AscI and PacI, blunted by T4 DNA polymerase, and self-ligated, producing the empty vector with no coding sequences. Because the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant displays abnormalities in silique and seed development (Nakashima et al., 2009), the srk2d srk2i double mutant, in which the T-DNA insertion in SRK2E was heterozygous, was used as the donor plant for Agrobacterium (Agrobacterium tumefaciens)-mediated transformation by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). In parallel with hygromycin selection, the transgenic plants in the srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant background were screened using primers designed to confirm the T-DNA insertions (Fujita et al., 2009). Homozygous transgenic plants of the T3 generation were used for analysis unless otherwise noted.

Stomatal Aperture Measurement

Stomatal apertures were examined as described in Fujita et al. (2009) with minor modifications. Fully expanded leaves of 5-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in soil under control or high RH conditions were detached and floated on stomatal opening buffer containing 20 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM 2-(n-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES; pH 6.15, potassium hydroxide [KOH]; Pei et al., 1998) for 2 h to preopen the stomata. Subsequently, ABA or ethanol (solvent control) was added to the opening buffer to a final concentration of 5 μM ABA. After 2 h of incubation, images of the abaxial epidermis were taken as described in Medeiros et al. (2017).

Analysis of Primary Metabolites Using GC-MS

Whole 12-day-old seedlings (∼100 mg) were harvested in MD, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C until further processing. The samples were homogenized using a ball mill precooled with liquid nitrogen and extracted in 1,400 μL of methanol. Subsequently, 60 μL of internal standard (0.2 mg ribitol mL−1 water) was added as a quantification standard. The extraction, derivatization, standard addition, and sample injection were conducted as described in Lisec et al. (2006). The GC-MS system comprised a CTC CombiPAL autosampler, an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph, and a LECO Pegasus III TOF-MS running in EI+ mode. Metabolites were identified by comparison to database entries of authentic standards (Kopka et al., 2005). Chromatograms and mass spectra were evaluated using Chroma TOF 1.0 (LECO) and TagFinder 4.0 software (Luedemann et al., 2008). Data presentation and experimental details are provided in Supplemental Data Set 2 following current reporting standards (Fernie et al., 2011). For k-means clustering, number of clusters, k (≈√N/2 = 5.20), was determined according to the crude rule of thumb (Mardia et al., 1979).

Measurement of Respiratory Parameters

Estimation of respiratory fluxes based on 14CO2 evolution was performed as described in Kühn et al. (2015) with minor modifications. Leaf discs were prepared from 5-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in soil under control or high RH conditions. Twenty leaf discs (6 mm in diameter) were incubated in 10 mM MES (pH 6.5, KOH) containing 1 mM of Glc labeled with 2.8 GBq mol−1 of 14C at position 1 or positions 3 and 4 (ARC0120A and ARC0211, respectively; American Radiolabeled Chemicals) in closed flasks at room temperature under light irradiation (∼100 μmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density). Evolved 14CO2 was trapped by 400 μL of 10% (w/v) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) inserted in the flask, and the trap was replaced by a new one every hour up to 4 h. The entire NaOH solution in the trap was mixed with 4 mL of scintillation cocktail (Rotiszint Eco Plus, ROTH), and radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (LS6500, Beckman Coulter).

Analysis of [U-14C]-Glc-Labeled Samples

Leaf discs were prepared from 5-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in soil under control or high RH conditions. Twenty leaf discs (6 mm in diameter) were incubated in 10 mM MES (pH 6.5, KOH) containing 1 mM of [U-14C]-Glc (7.0 GBq mol−1; MC144; Hartmann Analytic) in closed flasks at room temperature under light irradiation (∼100 μmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density). After incubation for 4 h, the leaf discs were placed in a sieve, washed several times in double-distilled water, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C until further processing. Evolved 14CO2 was trapped by 400 μL of 10% (w/v) NaOH inserted in the flask. Extraction and fractionation were performed as described in Szecowka et al. (2012) with minor modifications. Discs were extracted with 1 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol at 95°C, subsequently reextracted with 1 mL of 50% (v/v) ethanol, 1 mL of 20% (v/v) ethanol, and 1 mL of water, and the combined supernatants were dried and resuspended in 2 mL of water. A portion of the soluble fraction (750 µL) was subsequently separated into neutral, anionic, and basic fractions by ion-exchange chromatography; the neutral fraction (3.75 mL) was further analyzed by enzymatic digestion followed by a second ion-exchange chromatography step (Carrari et al., 2006). To measure phosphate esters, a portion of the soluble fraction (150 µL) was incubated in 50 μL of 10 mM MES (pH6.0, KOH) with 1 unit of potato acid phosphatase (grade II; Roche) for 3 h at 37°C and analyzed by ion-exchange chromatography (Fernie et al., 2001). The insoluble material that remained after ethanol extraction was homogenized, resuspended in 500 μL of water, and subjected to starch, protein, and cell wall measurements (Fernie et al., 2001). Metabolic fluxes were calculated following the assumptions described in detail in Geigenberger et al. (1997, 2000; Obata et al. (2017.

Analysis of [U-13C]-Glc-Labeled Samples

Fully expanded leaves of 5-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in soil under control or high RH conditions were detached with their petioles using a sharp razor and fed via the petiole with 15 mM [U-13C]-Glc (CLM-1396; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) by incubation in 10 mM MES (pH 6.5, KOH) for 2 h. At the end of incubation, the leaves were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until further processing. The homogenized samples were freeze-dried in a lyophilizer (Martin Christ), extracted, and analyzed using the same procedure described for the analysis of primary metabolites using GC-MS. The fractional enrichment of metabolite pools and total isotope redistribution were determined as described in Roessner-Tunali et al. (2004) and Tieman et al. (2006).

Analysis of Organic Acids and Phosphorylated Intermediates Using LC-MS/MS

Whole 12-d-old seedlings were collected at the EN, MD, and ED, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C until further processing. Extraction and quantification were performed as described in Lunn et al. (2006) with modifications as described in Figueroa et al. (2016).

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA extraction and microarray analysis were performed as described in Fujita et al. (2009). Microarray data for srk2d srk2e srk2i grown on agar plates for 12 d (Fujita et al., 2009) were reanalyzed by GeneSpring to filter the genes whose expression was significantly (P-value < 0.05) altered compared to wild type. A microarray analysis of the aba2-1 mutant grown under identical conditions was also performed, and the data were processed in the same way as that of srk2d srk2e srk2i. The genes annotated in the ARACYC 14.0 database available on the Plant Metabolic Network (www.plantcyc.org/databases/aracyc/14.0) were considered to be metabolism-associated genes. For RT-PCR and qRT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from 12-d-old seedlings of the srk2d srk2e srk2i, aba2-1, and areb1 areb2 abf3 abf1 mutants, the complementation lines, and wild type grown on agar plates as described in Bugos et al. (1995). Total RNA was extracted from seeds as described in Meng and Feldman (2010) with minor modifications. In brief, RNA was extracted in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% sarkosyl, 0.5% 2-mercaptoethanol) with phenol reagents. The precipitated RNA was resuspended in standard extraction buffer and purified according to the standard method (Bugos et al., 1995). One microgram of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with Maxima Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR analyses were performed using a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for the reactions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative expression levels were calculated by the comparative CT method with ACTIN2 as a reference gene. The primers used for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

The applied statistical tests and significance levels are indicated in each figure legend. The results of all analyses of variance (ANOVA) are summarized in Supplemental File.

Accession Numbers

The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative locus numbers for the major genes discussed in this article are as follows: SRK2D/SnRK2.2 (At3g50500), SRK2E/SnRK2.6/OST1 (At4g33950), SRK2I/SnRK2.3 (At5g66880), ABA2 (At1g52340), ABI3 (At3g24650), AREB1/ABF2 (At1g45249), AREB2/ABF4 (At3g19290), ABF3 (At4g34000), and ABF1 (At1g49720). The microarray design and data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress; accession numbers E-MEXP-2116 and E-MTAB-5723).

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Germination rates of the mutants involved in ABA signaling.

Supplemental Figure 2. Germination rates of the mutants involved in ABA signaling grown on agar plates with ABA.

Supplemental Figure 3. The number of leaves in the aba2-1 mutants decreases in response to exogenous ABA application.

Supplemental Figure 4. The srk2d srk2e srk2i triple mutant grows in a similar manner to wild type in terms of biomass and total leaf area.

Supplemental Figure 5. Germination and growth phenotypes of the T-DNA mutant of ABI3.