Abstract

Purpose of review:

Gastrointestinal transmural defects are defined as total rupture of the gastrointestinal wall and can be divided into three main categories: perforations, leaks and fistulas. Due to an increase in the number of therapeutic endoscopic procedures including full thickness resections and the increase incidence of complications related to bariatric surgeries there has been an increase the number of transmural defects seen in clinical practice and the number of non-invasive endoscopic treatment procedures used to treat these defects.

Recent findings:

The variety of endoscopic approaches and devices, including closure techniques using clips, endoloop and endoscopic sutures; covering techniques such as the cardiac septal occluder device, luminal stents and tissue sealants; and drainage techniques including endoscopic vacuum therapy, pigtail and septotomy with balloon dilation are transforming endoscopy as the first-line approach for therapy of these conditions.

Summary:

In this review, we describe the various transmural defects and the endoscopic techniques and devices used in their closure.

Keywords: LEAK, FISTULA, ENDOSCOPIC CLOSURE, BARIATRIC SURGERY, ACUTE PERFORATION, ACUTE LEAK, CHRONIC FISTULA, ADVERSE EVENTS, ENDOSCOPIC FULL THICKNESS, INTERNAL DRAINAGE, ENDOSCOPIC DEVICES

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) transmural defects are defined as total rupture of the gastrointestinal wall and are divided into three main categories: perforations, leaks and fistulas [1,2].

A GI perforation is defined as an acute rupture of the gastrointestinal wall and may occur as a result of endoscopic procedures, including endoscopic resections, dilation of stenosis or barotrauma. They also occur due to diseases such as Boerhaave’s syndrome, active ulceration, diverticulitis and appendicitis [1,3].

A GI leak is a communication between intra- and extra-luminal compartments due to a defect in the GI wall and often occur after surgery. Leaks are often located at the suture and anastomosis line [4,5].

A GI fistula is defined as an abnormal communication between two epithelialized surfaces. The most common causes include chronic inflammatory causes, malignance and untreated long-term leak. Fistulas can be divided into internal and external fistulas. An internal fistula is between an abdominal organ and another organ and external fistula is between an abdominal organ and the body surface [4,5].

Recognition of perforations, leaks and fistulas are essential for choosing the best treatment modality. Endoscopic closure is the most commonly used therapeutic procedure used in the treatment of an iatrogenic perforation. Endoscopic techniques have been shown to be highly effective in reducing morbidity and mortality in the treatment of all GI wall defects [2,6,7].

When determining the appropriate endoscopic approach for closure of luminal defects, certain fundamental principles should be considered. Undrained collections should be drained radiologically, surgically or endoscopically. In many cases endoscopic therapy can be used to interrupt or drain the flow of luminal contents through a GI defect. Several features must be considered to optimize outcomes, including defect size, shape of margin, viability of the surrounding tissue and location of the wall defect. In this review, we discuss the devices and techniques used in the management of endoscopic closure of transmural wall defects [5,8,9].

ENDOSCOPIC DEVICES USED IN THE CLOSURE OF WALL DEFECTS

Novel technologies and techniques are being developed that can be used in the treatment of transmural defects. The various devices include: through-the-scope clips (TTSC), cap mounted clips, covered self-expandable metal stents (CSEMS), tissue sealants, endoscopic sutures, cardiac septal defect occluders, septotomies, balloon dilators, endoscopic internal drainage with double pigtails (EID) and endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) [10–22]. The devices that are frequently used for closure of defects are summarized in table 1 and table 2 and are shown in figure 1.

Table 1.

Endoscopic Devices Used in the Closure or Covering of Transmural Defects

| Device/ Technique | Mechanism of action | Description | Best Use | Defect characteristics for success | Advantage(s) | Disadvange(s ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTSC | Closure | Hemostatic clips used to approximate tissue. Defect closure is off-label use, only the Resolution 360™ Clip (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) is FDA approved for this application. |

Acute wall defect: perforation | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: smaller than 1 to 2 cm) Margin: non-everted regular edges Tissue quality: healthy |

Ease of application | Limited to smaller defects and healthy tissue with regularmargins. |

| Cap mounted clips | Closure | Clips housed in distal attachment cap. Designed with internal prongs to approximate tissue for defect closure. | Acute/Chronic wall defect: perforation, leak and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: smaller than 3 cm Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: healthy |

Ease of application | Limited to smaller defects and healthy tissue. |

| Endoloop | Closure | Defects are approximated and sealed with endoloops alone or with clips. Defect closure is off-label use. |

Acute wall defect: perforation | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: between 3 to 5 cm Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: healthy |

Cheaper device for larger defects | Technically demanding Limited evidence |

| Endoscopic sutures | Closure | Can be used for interrupted or running full-thickness tissue apposition to close wall defects. | Acute/Chronic wall defect: perforation, leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: best for esophagus, stomach and rectum. Can be done in duodenum and colon but is challenging. Size: any size can be closed with the suture device Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: healthy |

Can be applied at complex wall defect | Technically demanding Not optimal for small spaces. Requires a double-channel endoscope |

| Cardiac septal occluder | Closure/ Covering | Nitinol, dumbbell shaped occluder plug with polyethylene terephthalate sewn-in patch. Defect closure is off-label use. |

Chronic leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: any size. You need to select the correct size of the device correlated to the defect size Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: unhealthy (well-established fistula tract) |

Ease of application | Limited evidence Expensive |

| Tissue sealants | Closure/ Covering | Can be used either by fistula embolization or Chronic fistula by submucosal injection into the edges of the fistula until the lumen is occluded. Other technique includes combining an absorbable mesh with a sealant application for larger fistula. Better results when used in conjunction with other endoscopic techniques. |

Chronic fistula | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: most effective in long narrow fistula tract. Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: unhealthy (well-established fistula tract) |

Ease of application | Rarely successful as mono-therapy Multiple sessions required Relatively expensive |

| Luminal Stents | Covering | Stent placement acts by covering the defect and diverting enteral contents. | Acute wall defect: perforationand leaks | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: best for esophagus and after bariatric surgery. Size: any size that the stents can cover Margin: non-everted Tissue quality: healthy or unhealthy |

Ease of application Better results in upper GI tract |

Only can be used in narrow lumens. Fully covered has higher chance of migration (should fixed in place) Partially covered can be difficult to remove |

Table 2.

Endoscopic Devices Used for the Drainage of Transmural Defects

| Device/ Technique | Mechanism of action | Description | Best use | Defect characteristics for success | Advantage (s) | Disadvantage (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septotomy | Draining | Frequently a septum is identified between the leak site (cavity) and gastric pouch. Sequential incisions can be performed using APC or electrical surgical knives over the septum towards to the staple line to allow communication between the extraluminal cavity (leak/fistula site) and the gastric lumen. |

Chronic leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract that has a “septum”. Most commonly after sleeve gastrectomy leaks. Size: any size Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: healthy or unhealthy (fibrotic) |

Low cost procedure Easily performed |

Just for selective cases (presence of “septum”) |

| Pigtail stents (Endoscopi c Internal drainage) | Draining | Guide the drainage towards the GI tract (internal drainage (ID)) while favoring the leak/fistula’s occlusion. The purpose is threefold: 1) help drain the cavity; 2) obstruct orifice and enable oral intake; 3) induce mechanical reepithelization (as a foreign body) in order to produce healing along the defects pathway. If an external drain is present it must be capped or removed. |

Acute and chronic leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract Size: any size, including large cavities Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: healthy or unhealthy |

Can be applied at complex wall defect geometry Low cost procedure Easily to perform |

Repeat procedures for stent exchanges |

| Endoscopic Vaccuum Therapy (EVT) | Draining | Consists of placing a sponge in the lumen (or in the abscess cavity) connected with a NG tube to a negative pressure system (− 125 mmHg). It seals the leak and decreases bacterial contamination promoting perfusion and granulation tissue proliferation. |

Acute and chronic leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract that the vacuum catheter can reach Size: any size, including large cavities Margin: non-everted or everted edges Tissue quality: unhealthy |

Sponge system can be customized for the defect/ Cavity | Repeat procedures every 4–5 days Risk of massive bleeding |

| Balloon dilation | Dilation of downstrea m stenosis is critical for leak resolution | The pneumatic achalasia balloon (AB) is used for dilation of sleeve stenosis downstream of the leak/fistula to promote antegrade flow and drainage. The hydrostatic balloon is used to dilate stenosis (anastomotic stenosis) below the leak/fistula, reducing the internal pressure of the organ and allowing better flow of secretions into the lumen. |

Acute and chronic leaks and fistulas | Location/distance from the entrance orifice: anywhere in the GI tract. The indication for AB is just after sleeve gastrectomy. For strictures the hydrostatic balloon is the best option. Size: N/A Margin: N/A Tissue quality: healthy. Unhealthy tissue has a higher risk of perforation. |

Easily to perform | Risk of perforation |

Figure 1. Endoscopic closuring techniques.

Label: 1. Closure of esophageal POEM access site using TTSCs; 2. A. Esophageal fistula (arrow), B. Closure perforation site with cap mounted clip, C. Fluoroscopy demonstrating no leakage after closure; 3. Endoloop technique; A. Wall defect., B. TTSC placed with an endoloop at the margin of the defect., C. Closing the endoloop approximating the edges of the defect., D. Final aspect of the defect closure; 4. Suturing a defect with endoscopic suture device; 5. Cardiac septal occluder sealing a chronic fistula after a sleeve gastrectomy; 6. Tissue sealants: cianoacrylate to closure fistula tract after endoscopic fisula closure; 7. Luminal bariatric stent for covering a sleeve gastrectomy fistula; 8. “Septum” between defect and lumen after a sleeve gastrectomy; 9. Achnkalasia balloon dilation after septotomy; 10. Internal drainage with double pigtail stents; 11. Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy (EVT); 12. A. Granulation tissue in the fistula tract during EVT, B. Esophageal scar (arrow) at site of prior fistula, after successful closure with EVT

MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL PERFORATIONS BASED ON ANATOMICAL LOCATION

Most GI perforations can be treated endoscopically. Perforations frequently occur in healthy tissue, which allows for excellent tissue approximation and promotes healing. A GI perforation is an emergency that require close monitoring even after endoscopic defect closure. The key to treatment is promptly identifying the defect and determining whether an endoscopic or surgical approach should be used. Management of life-threatening complications associated with GI perforations is critical [1,5,23]. When a perforation is suspected, the patient should be immediately stabilized, especially in regards to air under pressure, which can cause pneumoperitoneum, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium which requires urgent needle decompression. It is best to switch to carbon dioxide insufflation because this may prevent this tension, decreasing distention and rapidly diffusing after the defect is closed. The endoscopist must also be confident that there is no extra-luminal contamination before proceeding with endoscopic closure [1,10,23,24].

There are a variety of different endoscopic closure techniques and devices that can be used depending on defect location and size, timing of recognition and endoscopist expertise. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis demonstrated an 89.9% success rate in GI perforation endoscopic closure, with a success rate of 90.2% for TTSC and 87.8% for cap mounted clips. Suturing demonstrated a 100% success rate in closing colonic perforations. These studies suggest that endoscopic closure is both safe and effective and should be considered an alternative to surgery in select cases [25–27].

Below we describe endoscopic closure techniques based on anatomical location.

Esophagus

For small perforations TTSCs are indicated. However, for small perforations with everted edges, cap mounted clips should be used. For large perforations or defects associated with esophageal stenosis, CSEMS is indicated. Endoscopic suturing techniques are also indicated for large complex wall defect [10,23].

It is important to emphasize that partially CSEMS have lower migration rates. However, they are more challenging to remove, frequently making necessary the use of APC, EMR or the stent over stent technique. The fully CSEMS are easier to remove, however they are associated with a higher risk of stent migration and therefore stent fixation using suturing techniques or cap mounted clips is recommended. It is worth mentioning that endoscopic techniques in the proximal esophagus such as stent placement or endoscopic suturing are challenging both because of the small space and the intolerance of the patients, and for this reason, conservative treatment can be considered in stable patients [1,13,28].

Stomach

Most acute perforations are small and occur during endoscopic resections. Frequently, they can be successfully managed with TTSC and cap mounted clips. In larger defects endoscopic suturing and the omental patch closure techniques appear to be the best treatment modalities. Other options include clipping plus endoloop (this is best performed by opening the endoloop to encircle the defect and then clipping the endoloop in the place with numerous TTSC prior to closing the endoloop) and cap mounted clips [23, 29,30].

Duodenum and Biliary tract

The endoscopic treatment of duodenum and biliary perforations based on Stapfer et al. classification [31] are described below:

Type I (perforation of duodenal wall): due to biliopancreatic secretions immediate diagnosis and repair are needed. For small perforation TTSC or cap mounted clips are usefull, however, it may be challenging due to the position of the endoscope. Larger perforations frequently require immediate surgery, however depending on the skill of the endoscopist, suturing devices or endoloop technique can also be used. In select cases, a nasoenteral drain to divert pancreatobiliary fluids may be beneficial in the management of small bowel perforations [23,31,32].

Type II (peri-ampullary perforation): often occur during sphincterotomy or ampulectomy. Fully CSEMS and TTSC are the best options. The repair of periampullary defects with TTSC may be challenging due to the position of the endoscope. Surgical treatment is also an option depending in the patient clinical condition [23,31,32].

Type III (bile duct perfurations): are frequentelly small defects and treatment with adequate drainage is sufficient, so biliary stent placement is the best option [23,31,32].

Type IV (retroperitoneal microperforations): results from air leakage to the retroperitoneum with no obvious site of perforation. Frequently conservative treatment is sufficient, however sometimes percutaneous drainage is needed if the patient presents with infected collection [23,31,32].

Colorectal

As in other organs, small perforations can be closed with clips (TTSC or cap mounted clips). For large defects endoscopic suture has been well described with efficacy rivaling TTSC. Endoloop closure technique has also been used [25–27,33,34].

After endoscopic closure, further management should be dictated by the patient’s clinical condition. In cases where endoscopic treatment fails or in patients with deteriorating clinical status, hospitalization and surgical consultation should be pursued. Asymptomatic perforations recognized after 24 hours from the procedure can be managed conservatively [24,25].

Post-endoscopic closure antibiotics, no oral diet, hydration and pain medications are required. Some patients also require drainage of fluid collections which can be performed surgically or percutaneously. Parenteral nutrition is recommended in patients with who cannot tolerate PO intake for ≥ 7 days. Patients should be monitored for signs of sepsis and peritonitis that may require urgent surgical intervention [23,24,35].

Urgent surgery is preferred only when the perforation is large, there is peritoneal contamination, generalized peritonitis, sepsis, or deteriorating clinical condition [36–39].

Radiologic studies are also indicated after perforation closure, including imaging with soluble contrast and computed tomography which can demonstrate persistent leaks and detect extraluminal air, fluid collections or bleeding [23,38,39].

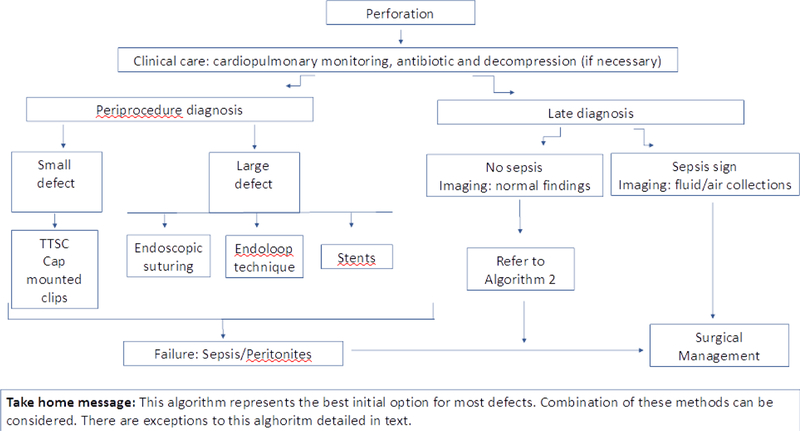

In summary, for small perforations of the GI tract TTSC or cap mounted clips should be used and for larger perforations endoscopic suturing appears to be most effective. However other different modalities can also be considered including endoloop technique and stents (Algorithm 1).

Algorithm 1.

Endoscopic closure in acute perforationpptx

MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL LEAKS AND FISTULAS

The clinical presentation of patients with GI leaks varies and frequently depends on if a surgical drain is in place. If a drain is in place, the leak can be identified early because there will be excessive drainage. If a drain is absent, the presentation of the leak is almost always infectious and related to the collection of liquid in sterile spaces [1,8,40].

The first step in diagnosing a leak or fistula is performing a thorough medical history and physical examination. Gastrointestinal leaks typically occur post surgically and represents an unnatural communication between intra and extraluminal compartments. A gastrointestinal fistula is an unnatural communication between the gut and hollow viscera and can result from a prolonged anastomotic leak. Patients often present with pain and fever, however, often times patients are asymptomatic. The source and route of the leak or fistula must be determined. Enterocutaneous fistula may be diagnosed based on physical examination as they often communicate with the skin. Internal GI fistula are more difficult to diagnose and a contrast fistulagram, CT, MRI and radionuclide test may be beneficial [40–42].

If conservative management is pursued, resuscitation and management of sepsis is important. Sepsis complications are the primary cause of mortality in patients with fistula. Successful control of sepsis is critical and depends on elimination of septic foci via image guided drainage and use of antibiotics [40–42].

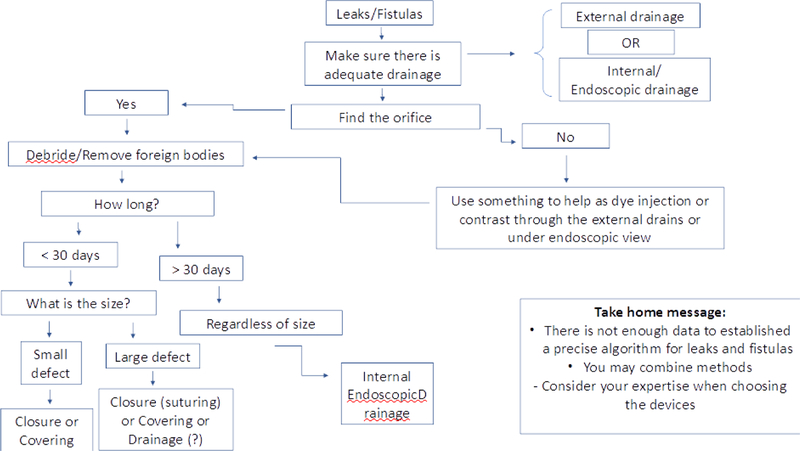

Endoscopic closure of a GI leak or fistula represents a major advancement in the treatment of patients. An appropriate endoscopic approach to leak and fistula closure includes several basic principles. Undrained cavities and collections of fluid must be initially drained. The size, viability of the surrounding tissue and the location of the defect should be defined. After this, the best endoscopic therapy for the patient can be chosen, which involves either closure, covering or draining the flow of luminal contents through the GI defect [40–42]. Algorithm 2 can be used to approach patients with GI leaks and fistulas.

Algorithm 2:

Endoscopic treatment for leaks and fistulas

MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL LEAKS

The most common endoscopically treated anastomotic surgical leak sites are: esophagojejunal after total gastrectomy and esophagogastric after distal esophagectomy in the upper GI tract; gastric after sleeve gastrectomy after bariatric procedures and gastrojejunal after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYBG); and colocolonic/colorectal after left colon resection, coloanal anastomosis after low anterior resection and ileoanal pouch anastomosis after proctocolectomy. Below we discussed these leaks based on position within the GI tract. The success rate decreases with the interval between the initial surgery and endoscopic treatment. Surgical options to treat a chronic gastric leaks are technically challenging and therefore unsuccessful in many cases [20,41,42].

Upper GI leaks

Esophagogastric and esophagojejunal leaks

Esophagogastric or jejunal anastomosic leaks are associated with a high postoperative mortality rate. These complications vary between 3 % and 11 % after total gastrectomy and between 3 % and 25 % after esophagectomy [43–48].

The most commonly used endoscopic therapies in the upper GI leaks are placement of CSEMS and cap mounted clips. TTSC are rarely used since they are not adequate (small and limited closure strength) to close most leaks. When the leak is diagnosed early, CSEMS is the best option, since it works much better in early leaks, presenting an average clinical success rate of 81% [1,49]. However, the CSEMS have several related adverse effects, including patient intolerance which often occurs when the proximal margin is close to the cricopharynx; and migration which occurs in about 20.8% of cases. The migration rates can be decreased with fixation of the proximal flange of the stent, either with suturing devices, cap mounted clips or nasal bridle technique. Metal stents present superior results compared to plastic stents, with less stent migration and reinterventions. Other complications such as bleeding or perforation related to the stent may occur, but those rare (2%) [50]. Cap mounted clips can also be used; however, its indications are limited to small defects in healthy tissue that occur shortly after surgery. The combination of methods such as glues, suturing and cap mounted clips with stents can also be performed [51–53].

In cases where conventional endoscopic treatment is not successful, endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT) and internal drainage with pigtails have been used effectively. EVT is a technique that allows internal drainage, thus controlling the infection and promoting tissue healing [20,41,54,55]. EVT is frequently used for gastroesophageal leaks with clinical success higher than 80%. The major problem with EVT is that every 4 to 5 days the patient undergoes a new endoscopic procedure to exchange the sponge system [54–56]. A recent study which included patients with anastomotic insufficiency secondary to esophagectomy or gastrectomy demonstrated 94.2% success of EVT, with a mean of 6 sponge system changes per patient, however, this study warned about the use of this technique reporting two deaths due to a fatal hemorrhage related to EVT [56]. Recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing EVT with esophageal stent demonstrated superior closure rate and shorter treatment time in favor of EVT [57].

A case series examining the association of sponge and stents was recently published. The technique, called stent-over-sponge (SOS), showed similar results, with a success rate of 71,4% as a first-line treatment and 80% as a second-line treatment, with no adverse events [58].

The internal drainage with double pigtails is an alternative technique that can be used and it easy to perform. Selective catheterization of the leak is performed and a double pigtail stent deployed, providing internal drainage, thus allowing tissue healing and leak and/or cavity closure. In the first series including leaks in various types of surgery, technical success was achieved in 100% of patients with a clinical success 82% [41].

Bariatric Surgery Associated Leaks

Obesity is a worldwide pandemic and bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment modality. Despite satisfactory clinical results associated with surgery, the number of complications after bariatric surgeries has increased due to broad adoption of the procedures [8,59].

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is traditionally the most performed surgery worldwide, however due to the “easier technique” of the procedure compared to RYGB, the popularity of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is rapidly increasing and according to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, is already the most performed surgery in the US [13,21,60]

Leaks are the most common complications associated with bariatric surgery, with rates varying from 0.4 to 5,6% after RYGB and 1.9% to 5.3% after LSG. The leak rates increase following revision surgeries [61–65].

Understanding the surgical anatomy, post procedural complications, and endoscopic techniques for optimal management is essential. Mainly in bariatric surgeries it is essential to treat the distal obstruction, either with balloon dilators or luminal stents; and to remove foreign bodies from the leak site such as staples, sutures, and external drains that may be close to the defect [8,63].

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

The leaks after RYGB may appear in several sites such as the gastric pouch, the gastrojejunal anastomosis (GJA), the excluded stomach and occasionally in the blind portion of the Roux limb and the jejunojejunal anastomosis. Precise diagnosis of the fistula site, either by imaging or endoscopic diagnosis is essential prior to any therapy [8,62].

Treatment with CSEMS is effective in the treatment of acute proximal leaks, including gastric pouch and GJA leaks, and the indicated CSEMS time ranges from 3 to 6 weeks, with an overall success of 76,1%. It’s important to note that the stent migration rate is about 30%, thus physicians should consider proximal stent fixation, either with endoscopic suturing or cap mounted clips or with the nasal bridle technique [13,14,28,61,66,67]. When GJA stenosis is present, it is essential to treat distal obstruction, either with CRE balloon (do not over dilate> 15 mm) or luminal stents, including lumen apposing metal stents which are less likely to migrate and theoretically also can be used in the treatment of GJA leaks [68,69].

Leaks in other topographies are not good candidates for stent placement and have worse outcomes. In the literature, some case series describe several options for endoscopic treatment of these leaks, including TTSCs, cap mounted clips, suturing devices and tissue sealants [40,70].

Asymptomatic gastrogastric fistulas can be managed with the use of proton pump inhibitors and dietary orientation. Endoscopic techniques include closure devices, such as endoscopic suturing. However, they present unsatisfactory long-term results, obtaining better outcomes in fistulas smaller than 1 cm [8, 53]. A new option for the treatment of weight regain in gastrogastric fistula patients is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty of the remaining stomach [71].

In chronic leaks and in leaks with a well-defined extraluminal cavity, EID is the best option, either with pig tails, EVT or septotomy following by achalasia balloon dilation. These modalities have presented satisfactory results in the management of these leaks [9,20,21,41,72].

Sleeve gastrectomy

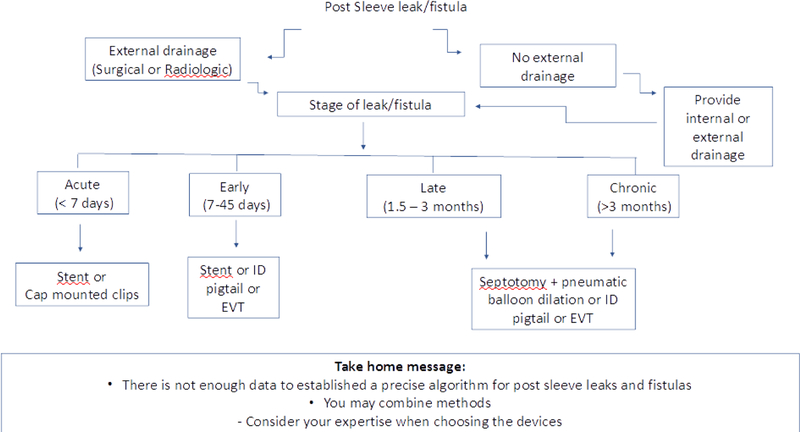

The most frequent sleeve leak occurs along the superior staple line just below the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). There are several methods to treat these leaks endoscopically and the CSEMS and endoscopic drainage techniques are often associated with best outcomes [8, 72]. The time of the leak, as classified in an international consensus is essential in choosing the appropriate treatment, as suggested in Algorithm 3 [73].

Algorithm 3.

How to treat a sleeve gastrectomy leak

If the leak is acute (< 7 days) or an early leak (<45 days) CSEMS are recommended. CSEMS work by covering the orifice of the leak and also shaping the stomach and treats distal stenosis [9, 72]. The overall success rate of CSEMS use was 72.8%, with a migration rate of 28.2% in one study [13]. A recent study showed that a newer stent (longer and with a larger diameter), called megastent, produced specifically for sleeve complications has led to superior results when compared to esophageal stents in the management of sleeve leaks [74]. In case of extraluminal collections in early leaks, drainage is needed (surgical, radiological or endoscopic). During endoscopic internal drainage it is possible to introduce the endoscope into the cavity to wash the contents, followed by the introduction of double pigtails or EVT [9,21,41,72,75–77].

For the treatment of late and chronic leaks, stents are not effective and therefore endoscopic internal drainage is indicated, either through septotomy followed by dilation with achalasia balloon, pigtails or EVT. The septotomy should only be performed if the presence of a septum between the perigastric cavity and the gastric lumen is identified in order to allow communication between them and should be followed by pneumatic balloon dilation in order to treat strictures and axis deviation of the sleeve, reducing the intragastric pressure [9,72,75,76].

Lower GI leaks

Anastomotic leaks that occur after colorectal resection, such as ileoanal anastomosis and mesorectal excision with coloanal anastomosis are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Distinguishing an anastomotic leak from a postoperative abscess can be challenging. The prevalence of this complication varies from 3% to 22% [4,78,79].

The distinction between free and contained anastomotic leak is important. A free anastomotic leak with peritonitis and sepsis must be treated surgically but patients with contained leaks may benefit from percutaneous or endoscopic drainage. A diverting ileostomy can be used to decreased the adverse events associated with anastomotic leaks [1,78,80].

Despite lower success rates, endoscopic therapies for lower GI leaks are similar to defects in the upper GI tract, and some of the same principles must be followed, including exploration and drainage of cavities close to the leak. It is difficult to make comparisons between techniques for treating lower GI tract leaks because of various definitions are used in the literature [78,79].

The use of cap mounted clips for small leaks is common worldwide, with variable success rates cited in the literature. As opposed to clipping techniques, SEMS are not often used to treat lower GI leaks, however, some groups showed a high success rate, with or without diverting ileostomy [78,81].

Endoscopic drainage therapies, especially EVT, present better results, and often are the best option in cases of contaminated collections. The early initiation of EVT and the presence of enteral diversion are factors that favor treatment success. This is successful in 79% of patients, however, patients that undergo early treatment or have enteral diversion have success rates of over 90%. As in any other treatment of leaks, neoadjuvant radio / chemotherapy becomes a challenging problem to close the leak [82,83].

The use of tissue adhesives such as glue fibrin has also been described with variable success rates and frequently requires several reinterventions. However, it still presents better results when used in combination with other therapies. Cyanoacrylate can also be used and has stronger adhesive properties than fibrin tissue sealant, and the efficacy for closures and leaks is well documented [52].

MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL FISTULAS

GI fistulas can occur after surgery, but they can also be caused by inflamed tissue (inflammatory bowel diseases), malignancy complications and radiation therapy. They are the most difficult transmural defect to close because there is an established epithelial tract near unhealthy tissue. Reepithelization of the tract using APC or brushes is often required, as well as diversion [1,15].

Patients with malignant esophagorespiratory fistula are very poor candidates for surgery and are best managed endoscopically by placing CSEMS [84,85].

The off-label use of a cardiac septal occluder device has produced satisfactory results in the management of upper gastrointestinal fistulas, but more studies are necessary to prove the efficacy [18,19].

The most common fistulas are those after bariatric surgical procedures. In contrast to acute leaks, fistula does not have good results with CSEMS placement [86]. Closing devices, such as cap mounted clips and suturing can be used with satisfactory immediate results, but late recurrence frequently occurs and remains a significant issue [53,87]. Gastrogastric fistulas closure through suturing also produces good immediate results, but the fistula recurs in more than 2/3 of patients [53,71].

Fistulas related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy/jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) procedures are rare and respond well to endoscopic treatment such as APC + TTSC, cap mounted clips and suturing [5–7,9,87].

Internal drainage with plastic double pigtails stents has been placed into or through the fistula tract to divert flow into the gastric lumen. Like pigtails, EVT is being used to optimize drainage, and this leads to effective sepsis control and has been showing successful fistula closure [41,77,82,83,88].

The incision (septotomy) of the “septum” between the fistula and the lumen using a needle knife or APC allows internal drainage and deviates fluids to the pouch with satisfactory clinical success [9,72,75,76].

Colonic fistula often communicates with other organs including the bladder and vagina and are the most difficult to treat endoscopically. The literature shows variable success with several devices, such as clips, sealants, cardiac septal occluders and EVT [6,17–19,25,26,52,53,88].

CONCLUSION

The appropriate management of patients with transmural defects requires a multidisciplinary team. Due to an increase in the number of therapeutic endoscopic procedures including full thickness resections and the increasing incidence of complications related to bariatric surgeries more non-invasive endoscopic treatment modalities have been developed to treat the complications associated with these surgeries. The variety of endoscopic approaches and devices, including closing, covering and drainage methods is transforming endoscopy as the first-line approach for therapy of transmural defects. There are limited data to inform the development of evidence-based recommendations and treatment algorithms. The best treatment approach is based on local expertise, device availability, and expert opinion. Randomized controlled trials comparing these modalities would be helpful to guide clinical decision making in the treatment of transmural defects moving forward.

Acknowledgments

Christopher Thompson reports fees as a consultant for Boston Scientific and Medtronic; fees as a consultant and institutional grants from USGI Medical, Olympus, and Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. Thompson also has a patent issued for Endoscopic Fistula Repair, held by Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Diogo de Moura and Amit Sachdey declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

••Of major importance

REFERENCES

- 1.Bemelman WA, Baron TH. Endoscopic Management of Transmural Defects, Including Leaks, Perforations, and Fistulae. Gastroenterology 2018. May;154(7):1938–1946.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustagi T, McCarty TR, Aslanian HR. Endoscopic Treatment of Gastrointestinal Perforations, Leaks, and Fistulae. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015. Nov-Dec;49(10):804–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar N, Thompson CC. A novel method for endoscopic perforation management by using abdominal exploration and full-thickness sutured closure. Gastrointest Endosc 2014. July;80(1):156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulfield H, Hyman NH. Anastomotic leak after low anterior resection: a spectrum of clinical entities. JAMA Surg 2013;148:177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho J, Sahakian AB. Endoscopic Closure of Gastrointestinal Fistulae and Leaks. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2018. April;28(2):233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haito-Chavez Y, Law JK, Kratt T, Arezzo A, et al. International multicenter experience with an over-the-scope clipping device for endoscopic management of GI defects (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2014. October;80(4):610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minami S, Gotoda T, Ono H, et al. Complete endoscopic closure of gastric perforation induced by endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer using endoclips can prevent surgery (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc 2006; 63: 596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.**.Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of Bariatric Surgery: What You Can Expect to See in Your GI Practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2017. November;112(11):1640–1655.This is a high quality overview with an excellent discussion of all the complications associated with bariatric surgery.

- 9.Campos JM, Ferreira FC, Teixeira AF, et al. Septotomy and Balloon Dilation to Treat Chronic Leak After Sleeve Gastrectomy: Technical Principles. Obes Surg 2016. August;26(8):1992–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yımaz B, Unlu O, Roach EC, et al. Endoscopic clips for the closure of acute iatrogenic perforations: Where do we stand? Dig Endosc 2015. September;27(6):641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Moura EG, Silva GL, de Moura ET, Pu LZ, de Castro VL, de Moura DT, Sallum RA. Esophageal perforation after epicardial ablation: an endoscopic approach. Endoscopy 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E592–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirschniak A, Kratt T, Stuker D, et al. A new endoscopic over-the-scope clip system for treatment of lesions and bleeding in the GI tract: first clinical experiences. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;66:162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.**.Okazaki O, Bernardo WM, Brunaldi VO, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Stents in the Treatment of Fistula After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2018. June;28(6):1788–1796.This is a well conducted systematic review discussing endoscopic treatments for bariatric fistulas using stents.

- 14.de Moura EG, Galvão-Neto MP, Ramos AC, et al. Extreme bariatric endoscopy: stenting to reconnect the pouch to the gastrojejunostomy after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2012. May;26(5):1481–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar N, Larsen MC, Thompson CC. Endoscopic Management of Gastrointestinal Fistulae. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2014. August;10(8):495–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repici A, Presbitero P, Carlino A, et al. First human case of esophagus-tracheal fistula closure by using a cardiac septal occluder (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:867–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melmed GY, Kar S, Geft I, et al. A new method for endoscopic closure of gastrocolonic fistula: novel application of a cardiac septal defect closure device (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:542–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HJ, Jung ES, Park MS, et al. Closure of a gastrotracheal fistula using a cardiac septal occluder device. Endoscopy 2011;43(Suppl 2):E53–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppola F, Boccuzzi G, Rossi G, et al. Cardiac septal umbrella for closure of a tracheoesophageal fistula. Endoscopy 2010;42(Suppl 2):E318–9. 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton NJ, Sharrock A, Rickard R, Mughal M. Systematic review of the use of endoluminal topical negative pressure in oesophageal leaks and perforations. Dis Esophagus 2017. February 1;30(3):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt F, Mennigen R, Vowinkel T, et al. Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy (EVT)-a New Concept for Complication Management in Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 2017. September;27(9):2499–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goenka MK, Goenka U. Endotherapy of leaks and fistula. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015. June 25;7(7):702–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogalski P, Daniluk J, Baniukiewicz A, et al. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal perforations, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol 2015. October 7;21(37):10542–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paspatis GA, Dumonceau JM, Barthet M, et al. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy 2014. August;46(8):693–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.*.Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M, Hajiyeva G, et al. Endoscopic management of colonic perforations: clips versus suturing closure (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2016. September;84(3):487–93.This retrospective study demonstrates the safety and efficacy associated with endoscopic suturing and its use in closing colonic perforations.

- 26.Kantsevoy SV, Bitner M, Davis JM, et al. Endoscopic suturing closure of large iatrogenic colonic perforation. Gastrointest Endosc 2015. October;82(4):754–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verlaan T, Voermans RP, van Berge Henegouwen MI et al. Endoscopic closure of acute perforations of the GI tract: a systematic review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:618–28.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilcox VT, Huang AY, Tariq N, Dunkin BJ. Endoscopic suture fixation of self-expanding metallic stents with and without submucosal injection. Surg Endosc 2015. January;29(1):24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stavropoulos SN, Modayil R, Friedel D. Closing perforations and postperforation management in endoscopy: esophagus and stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2015;25:29–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto N, Beppu K, Matsumoto K, et al. “Loop Clip”, a new closure device for large mucosal defects after EMR and ESD. Endoscopy 2008;40 Suppl 2:E97–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stapfer M, Selby RR, Stain SC, et al. Management of duodenal perforation after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy. Ann Surg 2000;232:191–198. 10903596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boumitri C, Kumta NA, Patel M, Kahaleh M. Closing perforations and postperforation management in endoscopy: duodenal, biliary, and colorectal. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2015; 25: 47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, et al. Endoscopic closure of a large iatrogenic rectal perforation using endoloop/clips technique. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2009. Jul-Sep;72(3):357–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangiavillano B, Viaggi P, Masci E. Endoscopic closure of acute iatrogenic perforations during diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy in the gastrointestinal tract using metallic clips: a literature review. J Dig Dis 2010. February;11(1):12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braga M, Ljungqvist O, Soeters P et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: surgery. Clin Nutr 2009; 28: 378–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raju GS, Saito Y, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic management of colonoscopic perforations (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74: 1380–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron TH, Wong Kee Song LM, Zielinski MD et al. A comprehensive approach to the management of acute endoscopic perforations (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 76: 838–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fatima J, Baron TH, Topazian MD et al. Pancreaticobiliary and duodenal perforations after periampullary endoscopic procedures: diagnosis and management. Arch Surg 2007; 142: 448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castellvi J, Pi F, Sueiras A et al. Colonoscopic perforation: useful parameters for early diagnosis and conservative treatment. Int J Colorect Dis 2011; 26: 1183–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merrifield BF, Lautz D, Thompson CC. Endoscopic repair of gastric leaks after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a less invasive approach. Gastrointest Endosc 2006. Apr;63(4):710–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donatelli G, Dumont JL, Cereatti F, et al. Endoscopic internal drainage as first-line treatment for fistula following gastrointestinal surgery: a case series. Endosc Int Open 2016. June;4(6):E647–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willingham FF, Buscaglia JM. Endoscopic Management of Gastrointestinal Leaks and Fistulae. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015. October;13(10):1714–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lang H, Piso P, Stukenborg C et al. Management and results of proximal anastomotic leaks in a series of 1114 total gastrectomies for gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2000; 26: 168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer L, Meyer F, Dralle H et al. Insufficiency risk of esophagojejunal anastomosis after total abdominal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2005; 390: 510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sierzega M, Kolodziejczyk P, Kulig J et al. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival after total gastrectomy for carcinoma of the stomach. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 1035–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Migita K, Takayama T, Matsumoto S et al. Risk factors for esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage after elective gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16: 1659–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarela AI, Tolan DJ, Harris K et al. Anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy for cancer: a mortality-free experience. J Am Coll Surg 2008; 206: 516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turkyilmaz A, Eroglu A, Aydin Y et al. The management of esophagogastric anastomotic leak after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2009; 22: 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Persson S, Rouvelas I, Kumagai K, et al. Treatment of esophageal anastomotic leakage with self-expanding metal stents: analysis of risk factors for treatment failure. Endosc Int Open 2016. April;4(4):E420–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dasari BV, Neely D, Kennedy A, et al. The role of esophageal stents in the management of esophageal anastomotic leaks and benign esophageal perforations. Ann Surg 2014. May;259(5):852–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.*.Manta R, Caruso A, Cellini C, et al. Endoscopic management of patients with post-surgical leaks involving the gastrointestinal tract: A large case series. United European Gastroenterol J 2016;4:770–777.This is a well conducted retrospective analysis discussing the endoscopic management of gastrointestinal leaks within the entire gastrointestinal tract.

- 52.Lippert E, Klebl FH, Schweller F, et al. Fibrin glue in the endoscopic treatment of fistulae and anastomotic leakages of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011. March;26(3):303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mukewar S, Kumar N, Catalano M, et al. Safety and efficacy of fistula closure by endoscopic suturing: a multi-center study. Endoscopy 2016. November;48(11):1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pines G, Bar I, Elami A, et al. Modified Endoscopic Vacuum Therapy for Nonhealing Esophageal Anastomotic Leak: Technique Description and Review of Literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2018. January;28(1):33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bludau M, Fuchs HF, Herbold T, et al. Results of endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure device for treatment of upper GI leaks. Surg Endosc 2017. December 7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.**.Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Neumann PA, et al. Successful closure of defects in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic vacuum therapy (EVT): a prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc 2017;31:2687–2696.This is a high quality prospective study showing the efficacy of EVT within the upper GI tract. This study warned about the use of EVT reporting two deaths due to a fatal hemorrhage related.

- 57.Rausa E, Asti E, Aiolfi A, et al. Comparison of endoscopic vacuum therapy versus endoscopic stenting for esophageal leaks:systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2018. June 25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Valli PV, Mertens JC, Kröger A, et al. Stent-over-sponge (SOS): a novel technique complementing endosponge therapy for foregut leaks and perforations. Endoscopy 2018. February;50(2):148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moura D, Oliveira J, De Moura EG, et al. Effectiveness of intragastric balloon for obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized control trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016. February;12(2):420–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013;23:427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puli SR, Spofford IS, Thompson CC. Use of self-expandable stents in the treatment of bariatric surgery leaks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones KB, Afram JD, Benotti PN, et al. Open versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a comparative study of over 25,000 open cases and the major laparoscopic bariatric reported series. Obes Surg 2006;16:721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zellmer JD, Mathiason MA, Kallies KJ, et al. Is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy a lower risk bariatric procedure compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? A meta-analysis. Am J Surg 2014;208:903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burgos AM, Braghetto I, Csendes A et al. Gastric leak after laparoscopic-sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Obes Surg 2009;19:1672–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aurora AR, Khaitan L, Saber AA. Sleeve gastrectomy and the risk of leak: a systematic analysis of 4,888 patients. Surg Endosc. Springer-Verlag 2012;26:1509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:935–8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, et al. Full covered self-expandable metal stents for the treatment of anastomotic leak using a silk thread. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017. July;96(29):e7439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jain D, Patel U, Ali S, et al. Efficacy and safety of lumen-apposing metal stent for benign gastrointestinal stricture. Ann Gastroenterol 2018. Jul-Aug;31(4):425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Moura EGH, Orso IRB, Aurélio EF, et al. Factors associated with complications or failure of endoscopic balloon dilation of anastomotic stricture secondary to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016. Mar-Apr;12(3):582–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhayani NH, Swanström LL. Endoscopic therapies for leaks and fistulas after bariatric surgery. Surg Innov 2014. February;21(1):90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulman AR, Huseini M, Thompson CC. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty of the remnant stomach in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a novel approach to a gastrogastric fistula with weight regain. Endoscopy 2018. June;50(6):E132–E133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baretta G, Campos J, Correia S, et al. Bariatric postoperative fistula: a life-saving endoscopic procedure. Surg Endosc 2015. July;29(7):1714–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenthal RJ; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012. Jan-Feb;8(1):8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Galloro G, Magno L, Musella M, et al. A novel dedicated endoscopic stent for staple-line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case series. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014. Jul-Aug;10(4):607–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.*.Mahadev S, Kumbhari V, Campos JM et al. Endoscopic septotomy: an effective approach for internal drainage of sleeve gastrectomy-associated collections. Endoscopy 2017;49:504–8.This is a retrospective analysis and an overview which described the use of septotomy to treat gastric sleeve leaks and their associated collections.

- 76.Haito-Chavez Y, Kumbhari V, Ngamruengphong S, et al. Septotomy: an adjunct endoscopic treatment for post-sleeve gastrectomy fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc 2016. February;83(2):456–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.*.Gonzalez JM, Lorenzo D, Guilbaud T, et al. Internal endoscopic drainage as first line or second line treatment in case of postsleeve gastrectomy fistulas. Endosc Int Open 2018. June;6(6):E745–E750.This is a retrospective study demonstrating the efficacy and safety of endoscopic internal drainage used for treatment of gastric sleeve leaks.

- 78.Lamazza A, Sterpetti AV, De Cesare A, et al. Endoscopic placement of self-expanding stents in patients with symptomatic anastomotic leakage after colorectal resection for cancer: long-term results. Endoscopy 2015. March;47(3):270–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hyman N, Manchester TL, Osler T, et al. Anastomotic leaks after intestinal anastomosis: it’s later than you think. Ann Surg 2007. February;245(2):254–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Damrauer SM, Bordeianou L, Berger D. Contained anastomotic leaks after colorectal surgery: are we too slow to act? Arch Surg 2009. April;144(4):333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lamazza A, Fiori E, Sterpetti AV, et al. Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metallic stents for rectovaginal fistula after colorectal resection: a comparison with proximal diverting ileostomy alone. Surg Endosc 2016. February;30(2):797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Arezzo A, Verra M, Passera R, et al. Long-term efficacy of endoscopic vacuum therapy for the treatment of colorectal anastomotic leaks. Dig Liver Dis 2015. April;47(4):342–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.**.Borstlap WAA, Musters GD, Stassen LPS, et al. Vacuum-assisted early transanal closure of leaking low colorectal anastomoses: the CLEAN study. Surg Endosc 2018. January;32(1):315–327.This is a high quality prospective study demonstrating the efficacy and safety of EVT in the treatment of lower gastrointestinal tract anastomotic fistulas.

- 84.Zhu HD, Guo JH, Mao AW et al. Conventional stents versus stents loaded with (125)iodine seeds for the treatment of unresectable oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spaander MC, Baron TH, Siersema PD, et al. Esophageal stenting for benign and malignant disease: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016;48:939–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Puig CA, Waked TM, Baron TH Sr, et al. The role of endoscopic stents in the management of chronic anastomotic and staple line leaks and chronic strictures after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:613–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Law R, Wong Kee Song LM, Irani S, et al. Immediate technical and delayed clinical outcome of fistula closure using an over-the-scope clip device. Surg Endosc 2015;29:1781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weidenhagen R, Gruetzner KU, Wiecken T, et al. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a new method. Surg Endosc 2008. August;22(8):1818–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]