Abstract

Problem

Technology can transform health care; future physicians need to keep pace to ensure optimal patient care. Because future doctors are poorly prepared in computer literacy, the authors designed a computer programming certificate course. This Innovation Report describes the course and findings from a qualitative study to understand the ways it prepares medical students to use computing science and technology in medicine.

Approach

The 14-month Computing for Medicine certificate course (C4M, offered beginning in February 2016), University of Toronto, is comprised of hands-on workshops to introduce programming accompanied by homework exercises, seminars by computer science experts on the application of programming to medicine, and coding projects. Using purposive and maximal variation sampling, 17 students who completed the course were interviewed from April–May 2017. Thematic analysis was performed using an iterative constant comparison approach.

Outcomes

Participants praised the C4M as an opportunity to achieve computer literacy—including language, syntax, and fundamental computational ideas (and their application to medicine)—and acquire or strengthen algorithmic and logical thinking skills for approaching problems. They highlighted that the course illustrated linkages between computer science and medicine. Participants acknowledged a sometimes-existent chasm between producers and users of technology in medicine, recommending two-way communication between the disciplines when developing technology for use in medicine.

Next Steps

We recommend that medical schools consider computer literacy an essential skill to foster future collaborative computing partnerships for improved technology use by physicians and optimal patient care. We encourage further evaluation of future iterations of the C4M and similar courses.

Problem

In the last few years, a number of medical schools have redesigned their curricula to add competencies and learning objectives around the sophisticated use of information technology, labeling it in a variety of ways, such as health informatics,1 biomedical informatics,2 or medical informatics.3 Although these efforts teach medical students about the use of technology in their future practices, they do not teach students how to write computer programs. Learn-to-code programs for medical schools are largely absent from medical school curricula. Given the lack of preparation of future doctors in computer literacy suggested by this omission, we designed a hands-on experience for students to learn basic computer programming skills, including how to code.

Our contention is that without such cross-domain understanding, computer science and medicine will continue to work in silos and that problems with technology adoption (e.g., poor understanding of value, lack of utility) will be perpetuated even though future physicians should be compelled to keep pace with technological advances, which can transform health care, to ensure optimal patient care.

The purpose of this Innovation Report is to briefly describe our elective computing course and discuss the findings from a qualitative study to understand how the course prepares medical students to use computing science and technology in medicine.

Approach

We developed, and in February 2016 began offering, a 14-month Computing for Medicine certificate course (C4M), for students enrolled in the University of Toronto MD program. The course was composed of three core phases: (1) a series of hands-on workshops to introduce programming (students with minimal prior programming experience received an additional introductory session) accompanied by homework exercises; (2) consolidation workshops to provide further instruction and practice; and (3) seminars delivered by experts from various computer science fields, who discussed the application of programming to medicine accompanied by coding projects that corresponded with each seminar. The course was a collaboration between the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine and Department of Computer Science and was taught by faculty from the Department of Computer Science.

Description of the C4M

We assigned students a skill level based on their self-reported prior programming experience.

Course details are as follows: In phase I, principles of programming, students participated in a series of programming workshops (three to four sessions depending on skill level over a 3-month period), which included didactic teaching, demonstrations, and smaller in-class practice exercises. In this phase, students were also required to complete larger coding exercises as homework before the next workshop, which was at least 2 weeks later. As mentioned above, students with minimal prior programming experience also completed an additional introductory session during this phase. The objectives of this phase were to enable students to write very basic Python programs; trace basic Python programs involving lists, dictionaries, and files; and recognize good practices in software design.

In phase II, consolidation (five sessions over a 4-month period), students attended workshops with a focus on the consolidation of learning over time. In this phase, they were required to complete two large medical-themed Python projects that involved nearly all of the programming concepts they had learned in phase I. The objectives of this phase were to enable students to write programs that combined concepts from phase I, write programs to solve a problem, use good practice in software design consistently, and use a debugger to find mistakes in a program written by another author.

Students progressed to phase III, enrichment (six sessions over a 7-month period), after having gained experience solving Python programming problems in phases I and II. In this phase, they enhanced their understanding of how computing can be applied to medicine through six 2-hour seminars conducted by experts in an area of computing related to medicine and computing science faculty who taught additional relevant programming or computer science concepts. Students were required to complete projects related to three of the seminars to demonstrate the application of knowledge and skills learned. There were a variety of project options available to encompass the full range of learning needs (from novice to more advanced learners), and students self-selected the projects they wanted to work on.

Course evaluations

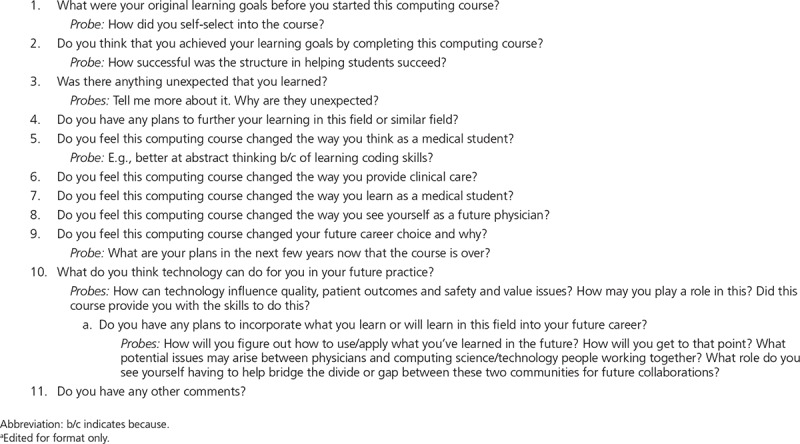

We conducted a qualitative evaluation (ethics approval was received from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board) to explore participants’ experiences and perceptions of the C4M. We applied purposive and maximal variation sampling (i.e., sampling based on prior programming experience and male/female) to recruit 17 students who had completed the course to participate in interviews. Interviewees received a $20 gift card for taking part in the study. On obtaining written consent, a research assistant with qualitative research experience (P.V.) conducted one-on-one in-person or phone interviews over a 1-month period (April–May 2017) using a semistructured interview guide (Appendix 1). Interviews were conducted to obtain theoretical saturation4 (i.e., until no new ideas were presented and participants’ evaluation of the course was well understood). Interviews ranged from 26 to 61 minutes (mean = 39 minutes, median = 34 minutes) and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Immediately following each interview, P.V. also documented field notes.

We conducted a thematic analysis5 of the transcripts using an iterative constant comparison approach, which emphasizes an inductive and open approach to data collection, allowing understanding to emerge through careful analysis of the data.4 Data were coded, compared with each other, and grouped into themes. An iterative approach to data collection helped to refine the interview questions and develop more targeted questioning. This continuous refinement of the research process yielded a substantive understanding of participants’ experiences and perceptions of the course.

Outcomes

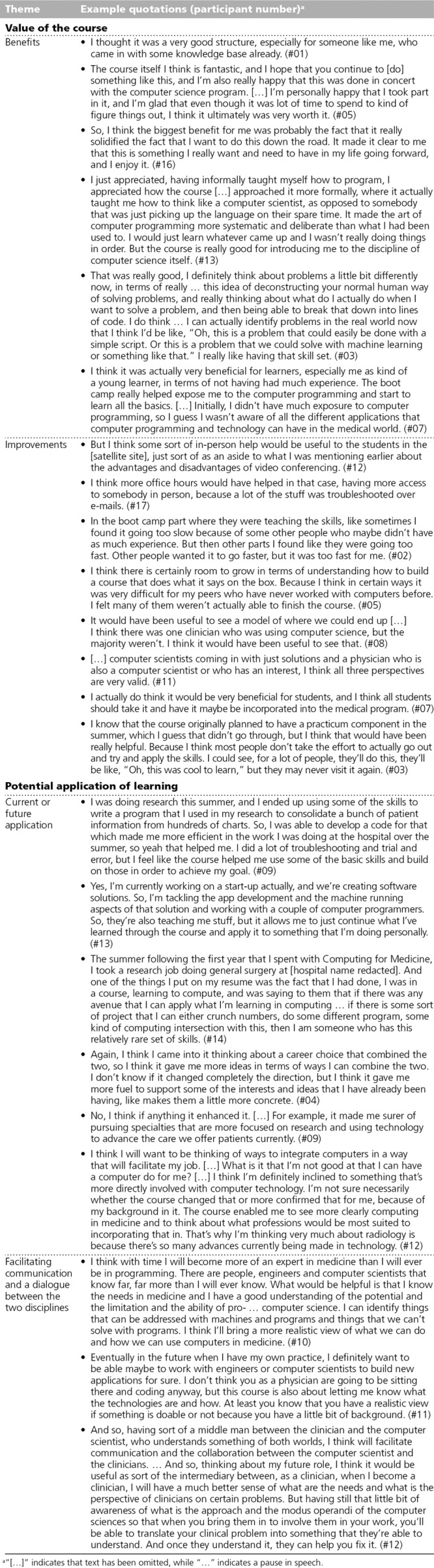

We classified data into two main themes: value of the course (with the subthemes of benefits and improvements) and potential application of learning (with the subthemes of current or future application and facilitating communication and a dialogue between the two disciplines). See Table 1 for example quotations.

Table 1.

Example Quotations, From Semistructured Interviews Exploring Participants’ (n = 17) Experiences and Perceptions of the Computing for Medicine Course, University of Toronto, April–May 2017

Value of the course

Benefits.

All participants highlighted the value of the C4M and reported that they liked the structure of the course, enjoyed the assignments and projects, and achieved their learning goals. Some students noted that their confidence in programming improved. Although some participants experienced frustration and felt overwhelmed at times (e.g., they—especially novice learners—were challenged by learning new concepts, struggled with finding time to practice, and had difficulty completing assignments), even these individuals stated that the structure was appropriate for enabling students to succeed. Most participants reported that the C4M provided them with a formal opportunity to learn computer programming skills as a legitimate part of their medical training, affording them an understanding of computer science and the nomenclature associated with the discipline. Participants generally attested that the course was well organized and that the facilitators were supportive, were approachable, and responded to questions in a timely fashion.

Aside from language and syntax, most participants described gaining a familiarization with fundamental computational ideas (e.g., understanding how machine learning can solve real-world problems). Many also reported acquiring or strengthening algorithmic and logical thinking skills. These skills expanded the ways that students thought about and approached problems. All participants reported that the C4M opened their eyes to the applicability of fundamental computational ideas to medicine and illustrated the linkages between the disciplines of medicine and computer science.

Improvements.

In addition to the benefits of the C4M, participants also recommended some improvements. Prominent suggestions included having more in-person help (e.g., for students at the satellite site, who were video conferenced into the course, and more office hours); finding ways to better tailor or customize the workshops to meet the learning needs of all learner levels from novice to experienced (i.e., some found it to be challenging, others found it to be too superficial, while others thought it was a good refresher); having experts who have a crossover role (clinical and computer science/technology) to present examples of projects that the average physician could reasonably integrate into their practice; expanding the C4M to the whole of the medical school, even at an introductory level, to spark greater interest in this field; and including a practicum opportunity.

Potential application of learning

Current or future application.

All participants indicated that they saw themselves using or would like to apply what they had learned in the C4M at some point in their careers. Some participants had already applied their learnings to research projects and summer jobs. Even participants whose interest in computer programming preceded enrollment recognized that the C4M enhanced or reinforced their interest and solidified some of their skills and thinking about how to combine these two fields in a career as well as the paths they might take to accomplish this.

Facilitating communication and a dialogue between the two disciplines.

Participants acknowledged a sometimes-present disconnect between the producers (computer scientists) and users (physicians) of technology in medicine. They suggested that part of the solution was to ensure two-way communication between the disciplines of computer science and medicine when developing technology that is meant to be adopted in medicine. Many participants described themselves as wanting to be part of this communication between the two disciplines. Participants articulated that promoting a dialogue between the two disciplines would ensure the development of realistic, usable, and effectively used technology.

Next Steps

Our findings suggest that students who participated in the C4M felt more prepared and motivated to promote a dialogue between the disciplines of computer science and medicine. Thus, in our experience, exposing students to computing science through a certificate program in the MD curriculum can reinforce a valuing and understanding of technology and encourage students to foster future collaborative computing partnerships. Given that technology is ubiquitous and changing rapidly, we recommend that medical schools consider computer literacy as an essential skill for future physicians. Teaching interested students computer literacy skills so that they have content knowledge and confidence will allow them to be ambassadors who can encourage their physician colleagues to engage with technology. At the same time, having computing language skills and motivation will enable physicians to communicate more effectively with technology developers. It is anticipated that such cross-domain understanding would result in improved technology use by physicians striving toward optimal patient care.

Much like the physician quality improvement movement of the past 10 years, which has been providing physicians with training and support for engaging in quality improvement, an investment in physicians’ confidence, knowledge, and skills in computing has the potential to similarly enhance the delivery of quality patient care. The question is: How this can be rolled out in a broader fashion? What should be elective, and what should be mandatory? Guzdial6 argues that computing educators who are teaching elective courses such as ours need to develop the learning goals for their materials by considering the eventual communities of practice and motivations of the learners. In addition, it may be worthwhile to consider applicants’ previous computing experiences and their interest in this topic area when making admissions decisions for these types of courses.

This Innovation Report explores the implementation of a computer programming certificate course for medical students at one Canadian medical school. Whether our data would hold true for other geographic contexts and whether making the course a mandatory one would yield different findings could be subjects for future research. Also, the participants we interviewed had self-selected into the course and completed it in its entirety. It is unknown whether students who did not fully complete it would have had similar views. We encourage further evaluation of future iterations of the C4M and similar courses to better understand learning transfer. Given the limitations of existing outcome-based evaluation models to capture the effects of health professions education,7 we chose qualitative inquiry to help us understand the complexities of the educational intervention and thus generate information that we hope will be useful for curriculum designers.

Appendix 1.

Semistructured Interview Guide, Used to Explore Participants’ (n = 17) Experiences and Perceptions of the Computing for Medicine Course, University of Toronto, April–May 2017a

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This project received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (protocol reference no. 34180).

References

- 1.Hersh WR, Gorman PN, Biagioli FE, Mohan V, Gold JA, Mejicano GC. Beyond information retrieval and electronic health record use: Competencies in clinical informatics for medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman H, Cohen T, Fridsma D. The evolution of a novel biomedical informatics curriculum for medical students. Acad Med. 2012;87:84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnette MH, De Groote SL, Dorsch JL. Medical informatics in the curriculum: Development and delivery of an online elective. J Med Libr Assoc. 2012;100:61–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 1967Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzdial M. Learner-centered design of computing education: Research on computing for everyone. Synth Lect Hum Cent Inform. 2015;8:1–165. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haji F, Morin MP, Parker K. Rethinking programme evaluation in health professions education: Beyond “did it work?” Med Educ. 2013;47:342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]