Abstract

Objective

Altered afferent input and central neural modulation are thought to contribute to fibromyalgia symptoms, and these processes converge within the spinal cord. We hypothesized that, using resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) of the cervical spinal cord, we would observe altered frequency dependent activity in fibromyalgia.

Methods

Cervical spinal cord rs-fMRI was performed in fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls. We analyzed a measure of low frequency oscillatory power, the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF), for frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz and frequency sub-bands, to determine regional and frequency-specific alterations in fibromyalgia. Functional connectivity and graph metrics were also analyzed.

Results

As compared to controls, greater ventral and lesser dorsal Mean ALFF of the cervical spinal cord was observed in fibromyalgia (p < 0.05, uncorrected) for frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz and all sub-bands. Additionally, lesser Mean ALFF within the right dorsal quadrant (p < 0.05, corrected) for frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz and sub-band frequencies 0.073 – 0.198 Hz was observed in fibromyalgia. Regional Mean ALFF was not correlated with pain, however, regional lesser Mean ALFF was correlated with fatigue in patients (r = 0.763, p = 0.001). Functional connectivity and graph metrics were similar between groups.

Conclusion

Our results indicate unbalanced activity between the ventral and dorsal cervical spinal cord in fibromyalgia. Increased ventral neural processes and decreased dorsal neural processes may reflect the presence of central sensitization and contribute to fatigue and other bodily symptoms in fibromyalgia.

Keywords: fMRI, fibromyalgia, ALFF, fALFF, low frequency oscillations, low frequency power, dorsal horn, ventral horn, dorsal columns, spinothalamic tract, widespread pain index, brief pain inventory, fatigue, central sensitization

INTRODUCTION

Fibromyalgia is a condition of widespread chronic pain typically accompanied by symptoms of fatigue, cognitive deficits, and affective symptoms of depression and anxiety (1). Chronic widespread pain conditions are thought to involve processes of central sensitization, an upregulated activity state of the central nervous system (CNS) (2), and may also involve impairments in descending modulation of pain (3), as well as altered peripheral nociceptive and non-nociceptive afferent inputs (4).

Evidence of altered CNS structure and activity have been observed in chronic pain states, including fibromyalgia (5). Altered brain activity in chronic pain occurs in response to various innocuous and noxious stimuli (e.g., (6,7)), as well as during resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) measured in terms of functional connectivity (8,9), functional networks (10,11), and low frequency oscillatory power (12–14). However, the complex underlying CNS processes that contribute to the initiation and maintenance of chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia remain unclear.

Multiple potential sources of altered nociceptive inputs and pain modulatory signals converge within the spinal cord making it an important part of the CNS to study to better understand chronic pain. Abnormal responses to innocuous and noxious stimulation (i.e., evidence of central sensitization) (15), increased primary afferent input from damaged peripheral nerves (4), as well as decreased brain/brainstem descending inhibition (and increased descending facilitation) of pain (3,16) occur in fibromyalgia and would be expected to impact spinal cord activity in fibromyalgia. Spinal cord responses to temporal summation of pain are altered in fibromyalgia (17), however, understanding of unprovoked spinal cord activity (i.e., resting state) may provide additional insights to how nociceptive and non-nociceptive information processing at the level of the spinal cord contribute to pain and comorbid symptoms in fibromyalgia.

We hypothesized that using rs-fMRI we would observe signals indicative of overall increased resting state activity (i.e., hyperactivity) within the cervical spinal cord in fibromyalgia. To test our hypothesis and improve our understanding of altered CNS activity in chronic pain, we analyzed rs-fMRI low frequency oscillatory power (18) to compare regional spinal cord fMRI activity in patients and healthy controls. We also investigated functional connectivity and the topological properties of the cervical spinal cord functional network.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Participants

Sixteen individuals with fibromyalgia and 17 healthy individuals participated in the study. Study recruitment and data collection were conducted over a period of 4 months: May through August 2016. All patients met inclusion criteria as follows: modified American College of Rheumatology 2011 criteria for fibromyalgia Rheumatology 2011 criteria for fibromyalgia [widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 + symptom severity (SS) ≥ 5, or WPI 3–6 + SS ≥ 9; symptoms present at a similar level for at least 3 months; no disorder that would otherwise explain the pain] (19), pain in all 4 body quadrants, average pain over the previous month of at least 2 (0–10 verbal scale), not pregnant or nursing, no MRI contraindications (e.g., metallic implants, claustrophobia), not taking opioid medications, and no depression or anxiety disorder. Patients were allowed to take their medications during the study (see Supplementary Methods for list of medications). Healthy control participants had no chronic pain, were not pregnant or nursing, had no MRI contraindications, were not taking pain or mood-altering medications at the time of the study, and had no depression or anxiety disorder. All participants signed written informed consent acknowledging their willingness to participate in the study, comprehension of all study procedures, and understanding that they could withdraw from the study at any time. All study procedures were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Study Procedures

All study procedures were conducted at the Richard M. Lucas Center for Imaging at Stanford University. Prior to MRI scanning, participants 1) were screened for any MRI contraindications, and 2) completed behavioral, psychological, and clinical questionnaires.

Questionnaires included the Fibromyalgia 2011 Diagnostic Criteria (19) for Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity (SS) scores, Sensory Hypersensitivity Scale (SHS) (20), PROMIS Fatigue (21), and Short Form Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (22). Quantitative sensory testing (QST) was conducted immediately after the MRI scan and assessed pressure pain thresholds, mechanical hyperalgesia, mechanical temporal summation, and response to a cold pressor test (see Supplementary Methods). Additional questionnaires and brain scans were collected but were not included in the present analysis.

MRI Scans

Functional imaging was performed using a 2D gradient-echo (GE) echo-planar-imaging (EPI) sequence with the field-of-view (FOV) centered at the C6 vertebra and spanning from the top of the C5 vertebra to the bottom of the C7 vertebra (Fig. 1). Structural imaging was performed using a high-resolution 3D fast spin-echo (FSE) T2-weighted sequence (Cube) spanning from the brainstem to the upper thoracic spine and a 2D axial multi-echo recombined GE sequence (MERGE) for spinal cord white matter-gray matter imaging (centered at C6 vertebra but larger FOV than the functional imaging). Details of scan procedures and parameters are included in the Supplementary Methods. Participants provided pain ratings before and after the fMRI scans. A verbal 0 – 10 scale with anchors of no pain (0) and worst imaginable pain (10) was used.

Figure 1. FMRI Scan Prescription Location.

The fMRI scan slices were prescribed to include the C5 - C7 cervical spine vertebrae corresponding to the C6 - C8 spinal cord segments. Underlay image is from one subject’s T2-weighted structural image.

Image Preprocessing

Preprocessing of the functional cervical spinal cord images was performed as previously reported by our group (23,24) using a combination of in-house customized scripts, the Oxford Center for Functional MRI of the Brain’s (FMRIB) Software Library (FSL), and the Spinal Cord Toolbox version 3.0 (25,26) (see Supplementary Methods).

Mean ALFF Analysis

The analysis of low frequency oscillatory power in the CNS can be measured using the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF), and this type of measurement possesses several advantages for rs-fMRI analysis. These analyses are free of the constraints of functional connectivity, which requires comparison and correlation of activity across selected voxels, regions of interest, networks, etc. In contrast, ALFF provides independent measures of activity on a per-voxel basis that can be calculated per subject and compared across groups of patients and controls. ALFF has high test-retest reliability and is more sensitive to group-level and individual differences than fractional ALFF (fALFF) (27), and brain and cervical spinal cord Mean ALFF can differentiate clinical populations (12,28).

Measures of Mean ALFF were calculated across all voxels of the preprocessed functional cervical spinal cord data, separately for each subject, using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI Advance Edition (DPARSFA) Toolbox (29), running in Matlab R2015b. In our primary analyses, Mean ALFF measures were calculated across low frequencies: 0.01 – 0.198 Hz and assessed for group differences. In secondary analyses, Mean ALFF measures were calculated separately for sub-band frequencies (30) including Slow5 (0.01 – 0.027 Hz), Slow4 (0.027 – 0.073 Hz), and Slow3 (0.073 – 0.198 Hz) (see Supplementary Methods).

Normalized (z-transformed) ALFF images were analyzed for group differences using FSL’s randomise. For this, the normalized ALFF images (one per subject) were concatenated into one image, and then the image (1 volume per subject, 29 volumes) was processed using randomise as a two-sample unpaired t-test of the images (31). Significance of the findings was assessed using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) at a uncorrected and corrected p < 0.05 (5,000 permutations).

Additional analyses included gray matter and white matter Mean ALFF comparison for validation of our measurements, fALFF analysis, and correlation analysis between greater and lesser region Mean ALFF (see Supplementary Methods).

Correlation Analyses of Regional Mean ALFF Power with Symptom and Quantitative Sensory Testing Measures

Mean ALFF values extracted from regions of greater Mean ALFF and lesser Mean ALFF for frequencies 0.01–0.198 Hz (uncorrected and corrected p < 0.05) were evaluated for correlations with symptom measures (IBM, SPSS Statistics, version 21). Symptom measures for the correlation analyses included: average scan pain (mean of pre and post scan ratings), fibromyalgia criteria widespread pain index (WPI) score, fibromyalgia criteria symptom severity (SS) score, sensory hypersensitivity (SHS), fatigue (PROMIS Fatigue), pain severity (BPI), and pain interference (BPI). The multiple symptom measures were chosen for their broad representation of sensory aspects of chronic pain (e.g., distribution of painful areas, extent of other bodily symptoms, hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, sensation and experience of fatigue, average experienced pain intensity, and average experienced pain interference, respectively). All of the pain and fatigue measures were correlated except for sensory hypersensitivity. Therefore, correlations were Bonferroni corrected for inclusion of 5 (correlated symptom measures + sensory hypersensitivity + 3 sets of Mean ALFF values) independent measures (uncorrected p < 0.05 / 5 uncorrelated measures = corrected p < 0.01). Additional exploratory analyses were conducted between QST data and Mean ALFF (see Supplementary Methods).

Seed-Based Functional Connectivity and Network Analysis

Functional connectivity measures the temporal correlation of signals between regions in the CNS and has been extensively used to assess the functional organization of communication within the brain. More recently, this line of research has extended to study the functional organization of intrinsic spinal cord networks. Growing evidence supports the presence of bilateral motor (left and right ventral horn functional connectivity) and bilateral sensory (left and right dorsal horn functional connectivity) rs-fMRI spinal cord networks (32–34), and the functional organization within these networks is altered in non-human primates after spinal cord injury and in humans during unilateral thermal stimulation (24,35). As aberrant sensory processing within the spinal cord is thought to partially underlie fibromyalgia, we also investigated the functional organization of spinal cord networks in the present study.

To investigate spinal cord functional connectivity, we employed a seed-based region of interest (ROI) approach similar to that recently reported by our group (24). The strength of functional connectivity was assessed between the left-ventral, left-dorsal, right-dorsal, and right-ventral horns at five levels evenly distributed superiorly and inferiorly across the cervical spinal cord FOV (20 ROI’s total). We also explored the topological properties of the functional network using the graph metrics of efficiency, small worldness, and modularity (see Supplementary Methods).

RESULTS

Data from four participants were excluded from the final analysis due to poor rs-fMRI image quality, and incorrect rs-fMRI prescription (see Supplementary Methods). Thus, data from 15 patients and 14 controls were included in the analysis.

Participant Demographics, Medications, Behavioral and Clinical Measures

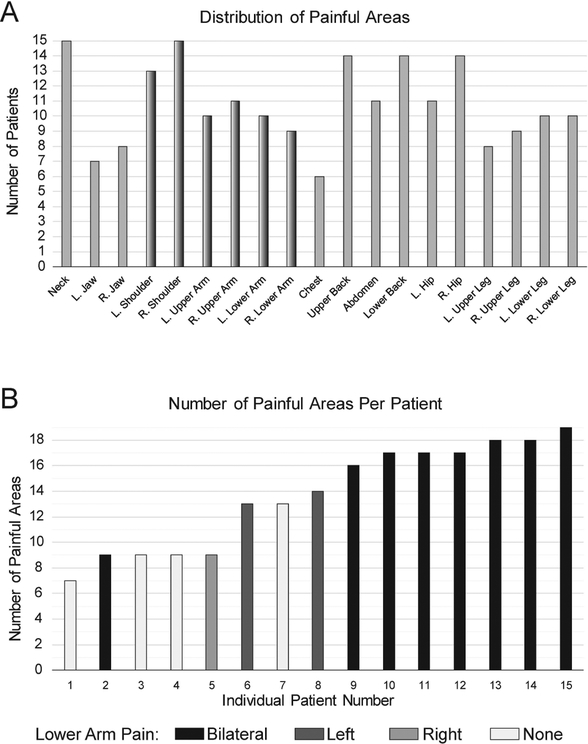

Patients demonstrated significantly greater symptom measures related to pain, sensory hypersensitivity, and fatigue as compared with controls (Table 1). Patients reported widespread pain symptoms across the body typical of fibromyalgia (Fig. 2). We hypothesized that altered cervical spinal cord activity would be apparent in fibromyalgia due to central sensitization, as an overall state of the CNS, rather than due to pain at corresponding dermatomes. However, all patients reported right shoulder pain and most reported arm pain, therefore our observations may be influenced by altered afferent nociceptive input from C6 - C8 dermatomes.

Table 1.

Demographic and Symptom Measures

| Controls | Patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std Dev | N | Mean | Std Dev | P-value | |

| Age | 14 | 48.71 | 11.10 | 15 | 47.13 | 9.82 | 0.687 |

| WPI Score | 14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15 | 13.80 | 3.53 | <0.001* |

| SS Score | 14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15 | 8.27 | 1.94 | <0.001* |

| Sensory Hypersensitivity (SHS) | 14 | 72.50 | 13.50 | 15 | 103.13 | 13.27 | <0.001* |

| Fatigue (PROMIS) | 14 | 48.19 | 6.83 | 15 | 64.18 | 7.45 | <0.001* |

| Pain Severity (BPI) | 14 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 15 | 5.14 | 1.82 | <0.001* |

| Pain Interference (BPI) | 10 | 0.61 | 1.07 | 15 | 5.05 | 2.52 | <0.001* |

Abbreviations: Std Dev, standard deviation; WPI, widespread pain index; SS, symptom severity; SHS, sensory hypersensitivity scale; PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; BPI, brief pain inventory; P-value, significance (2-tailed independent samples t-test); N, number of subjects.

p< 0.05

Figure 2. Distribution and Number of Painful Areas.

A) Patients with fibromyalgia (N=15) reported distributed regions of pain including dermatomes projecting to imaged spinal cord segments (dermatomes C6–C8, corresponding to C5–C7 vertebrae, shaded). B) All patients reported multiple regions of pain; the majority reported >12 regions of pain and all reported right shoulder pain (maximum number of regions = 19). Shading indicates patients with lower arm pain. R., Right; L., Left.

Altered Regional Spinal Cord Mean ALFF in Fibromyalgia

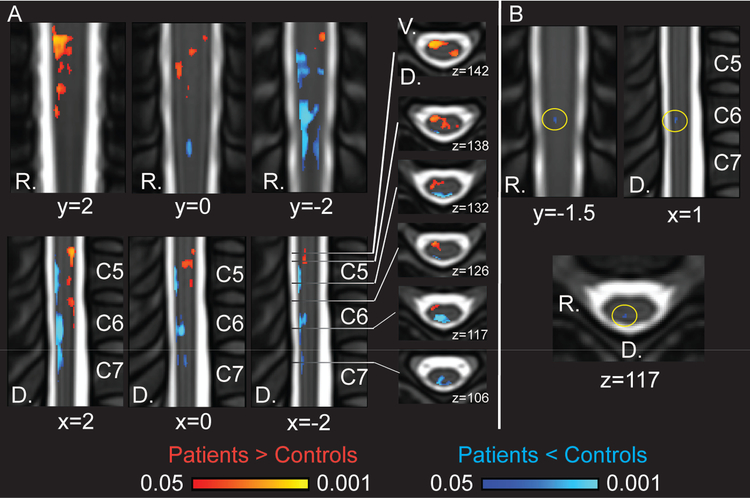

The main analyses of spinal cord low frequency oscillatory power using ALFF revealed group differences distributed across all imaged segments of the spinal cord (C6 - C8 dermatomes, corresponding to C5 - C7 vertebrae) for frequency range 0.01 – 0.198 Hz (uncorrected p < 0.05) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Greater Mean ALFF was observed primarily within the ventral hemi-cord of the cervical spinal cord in fibromyalgia, corresponding to the location of the right spinothalamic tracts and ventral horn. Lesser Mean ALFF was observed primarily within the dorsal quadrants of the cervical spinal cord in fibromyalgia, corresponding to the right spinal cord dorsal columns (i.e., medial lemniscus) and right dorsal horn. At the corrected threshold of p < 0.05, a small region of lesser Mean ALFF within the right dorsal quadrant of the spinal cord at the C7 dermatome / C6 vertebra level was observed in fibromyalgia.

Figure 3. Mean ALFF Group Differences for Frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz.

A) Coronal (top row), sagittal (bottom row), and horizontal/axial (right) views of cervical spinal cord Mean ALFF differences in patients as compared with controls for 0.01 – 0.198 Hz. Patients demonstrated greater ventral and lesser dorsal Mean ALFF (randomise TFCE p < 0.05 uncorrected). Greater Mean ALFF in patients: left dorsal 217 voxels, left ventral 30 voxels, right dorsal 72 voxels, right ventral 966 voxels; lesser Mean ALFF in patients: left dorsal 475 voxels, left ventral 0 voxels, right dorsal 1287 voxels, right ventral 13 voxels. B) Small cluster in dorsal spinal cord of lesser Mean ALFF in patients (randomise TFCE p < 0.05 corrected, 9 voxels). The coordinates are based on the PAM50 template coordinates. D, dorsal; R, right.

Additional frequency sub-band analyses revealed similar patterns of Mean ALFF group differences at the uncorrected threshold level (uncorrected p < 0.05) with greater ventral and lesser dorsal Mean ALFF in patients. At the corrected threshold (corrected p < 0.05) the frequency sub-band of 0.073 – 0.198 Hz (Slow3) revealed a small cluster of lesser Mean ALFF in patients within the dorsal right quadrant of the spinal cord at the C7 dermatome / C6 vertebral level (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). No group differences were observed at the corrected threshold (corrected p < 0.05) for frequency sub-bands of 0.027 – 0.073 Hz (Slow4) and 0.01 – 0.027 Hz (Slow5) therefore these frequency results were not analyzed or discussed further (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Additional analyses confirmed that Mean ALFF was greater in gray matter than white matter in agreement with previous reports (27) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Mean ALFF for patients > controls (uncorrected) and patients < controls (uncorrected) was negatively correlated across patient and control groups combined (N = 29, r = −0.508, p = 0.005) but not significant in the patient group (r = −0.266, p = 0.338). No group differences for fALFF were observed at the corrected threshold (corrected p<0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Correlations of Regional Mean ALFF with Symptom and Quantitative Sensory Testing Measures

Mean ALFF for patients > controls (uncorrected), patients < controls (uncorrected), and patients < controls (corrected) was assessed for correlations with multiple symptom measures. Mean ALFF for patients < controls (uncorrected) was positively correlated with fatigue (PROMIS Fatigue) in patients (r = 0.763, p = 0.001), however, this correlation was not significant for patients > controls (uncorrected), nor patients < controls (corrected) (Table 2) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Mean ALFF was not correlated with mean scan pain (average of pre and post scan ratings) (Table 2)(Supplementary Fig. 6). Mean ALFF was not significantly associated with additional measures including widespread pain index scores (WPI), symptom severity scores (SS), sensory hypersensitivity (SHS), pain severity (BPI), nor pain interference (BPI) in patients (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 7). All significant and non-significant associations across both groups (i.e., patients and controls combined) are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Mean ALFF and Symptom Measures

| ALFF Patients > Controls (uncorrected) |

ALFF Patients < Controls (uncorrected) |

ALFF Patients < Controls (corrected) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| Average Scan Pain | −0.007 | 0.98 | 0.029 | 0.918 | −0.197 | 0.481 |

| WPI Score | 0.038 | 0.894 | 0.157 | 0.577 | −0.053 | 0.853 |

| SS Score | −0.049 | 0.863 | 0.264 | 0.342 | 0.093 | 0.74 |

| Sensory Hypersensitivity (SHS) | −0.235 | 0.4 | −0.036 | 0.899 | −0.178 | 0.525 |

| Fatigue (PROMIS) | −0.229 | 0.411 | .763** | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.968 |

| Pain Severity (BPI) | −0.224 | 0.423 | −0.071 | 0.802 | −0.127 | 0.653 |

| Pain Interference (BPI) | 0.071 | 0.801 | 0.136 | 0.629 | 0.226 | 0.417 |

Pearson correlations between Mean ALFF (0.01 − 0.198 Hz) and symptom measures in patients (N=15). Abbreviations: ALFF, amplitude of low frequency fluctuations; WPI, widespread pain index; SS, symptom severity; SHS, sensory hypersensitivity scale; PROMIS, patient-reported outcomes measurement information system; BPI, brief pain inventory; r, Pearson correlation; p, significance (2-tailed).

p < 0.01

No significant correlations were identified between Mean ALFF and QST measures in the patient group (Supplementary Table 3). However, for cold pressor test duration, a positive association (trend) was identified with Mean ALFF patients < controls (uncorrected) in the patient group (N = 15, r = 0.489, p = 0.065).

Unaltered Functional Connectivity in Fibromyalgia

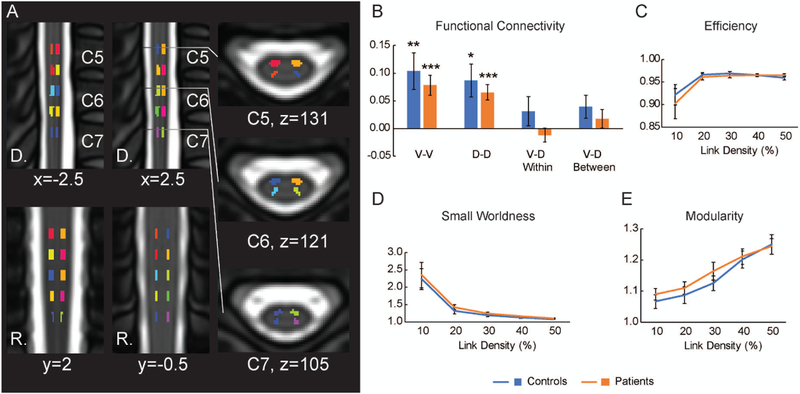

The mean ventral-ventral (V-V), dorsal-dorsal (D-D), ventral-dorsal within (V-D within) hemi-cord, and ventral-dorsal between (V-D between) hemi-cord functional connectivity were analyzed. Bilateral motor (V-V functional connectivity) and sensory (D-D functional connectivity) functional spinal cord networks have been observed and reproduced across studies in healthy individuals (24,32–34,36). In alignment with these previous observations, we observed significant V-V connectivity (r > 0) for both the patients (mean r ± 1 SE = 0.078 ± 0.018, p < 0.001) and controls (r = 0.104 ± 0.033, p = 0.008) as well as significant D-D connectivity for both the patients (r = 0.065 ± 0.014, p < 0.001) and controls (r = 0.087 ± 0.030, p = 0.013). No significant V-D within hemi-cord connectivity or V-D between hemi-cord connectivity was observed for either the patients or controls (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4). No significant group differences were observed in the V-V (p = 0.503) or D-D (p = 0.514) functional connectivity, indicating similar strength of the bilateral motor and sensory functional spinal cord networks in patients as compared with controls. Neither V-D within hemi-cord connectivity (p = 0.149) nor V-D between hemi-cord connectivity (p = 0.409) differed between the groups. Using graph metrics, the functional spinal cord network demonstrated small world properties at the lower link densities for patients and controls as previously reported (24,37). Mean small worldness at the 10% link density was 2.354 ± 0.365 and 2.240 ± 0.302 for the patients and controls, respectively. No group differences were found between the groups for any of the graph metrics, which included efficiency, small worldness, and modularity (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Functional Connectivity and Graph Metrics.

A) The regions of interest (ROIs) used to assess the functional spinal cord network are shown. The strength of functional connectivity was assessed between the left-ventral, left-dorsal, right-dorsal, and right-ventral horns at five levels evenly distributed superiorly and inferiorly across the cervical spinal cord (20 ROIs total). B) Significant ventral-ventral (V-V, bilateral motor network) and dorsal-dorsal (D-D, bilateral sensory network) functional connectivity was identified for each group (r > 0, one-sample t-test). No significant ventral-dorsal (V-D) within or V-D between hemi-cord connectivity was present, and no group differences in the strength of functional connectivity were observed. D) The functional networks demonstrated small world properties (small worldness > 1) as previously reported. However, no significant group differences were observed between the graph metrics of efficiency (C), small worldness (D), or modularity (E). The coordinates are based on the PAM50 template coordinates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

We report novel evidence of altered rs-fMRI low frequency power (Mean ALFF) in the cervical spinal cord in patients with fibromyalgia ー specifically, distributed patterns of greater regional Mean ALFF located within the ventral spinal cord and lesser regional Mean ALFF within the dorsal spinal cord. The most salient group difference in Mean ALFF was located within a small cluster in the spinal cord right dorsal quadrant located at the borderline of the dorsal horn gray matter and white matter. Individual differences in Mean ALFF, for patients < controls (uncorrected), were strongly positively correlated with levels of fatigue in patients. Together these results suggest regional differences in nociceptive and non-nociceptive processing pathways in fibromyalgia.

Altered Spinal Cord Mean ALFF in Fibromyalgia

Across frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz, patients demonstrated greater Mean ALFF within distributed ventral regions and lesser Mean ALFF within dorsal regions relative to controls. A small region of robust lesser Mean ALFF within the right dorsal quadrant was observed for frequencies 0.01 – 0.198 Hz and sub-band frequencies 0.073 – 0.198 Hz (corrected p < 0.05), but not for other sub-bands. Neuropathic pain patients demonstrate increased ALFF in the thalamus, somatosensory cortex, and brainstem nuclei, most strongly within the Slow4 frequency sub-band (0.023 – 0.073 Hz), and neural oscillations due to astrocyte calcium signaling may underlie these changes (12). We observed similar ALFF differences in the Slow4 frequency range at the uncorrected threshold. Due to technological limitations of spinal cord fMRI, we report these uncorrected observations for future use and propose that similar mechanisms may contribute to these findings (see Supplementary Methods).

Resting state fMRI activity (based on the blood oxygenation level dependent signal, BOLD) is typically associated with gray matter, however, reliable BOLD signal changes are also observed in white matter (38), and astrocytes (abundant in both gray and white matter) contribute to the BOLD fMRI signal (39). The group differences in Mean ALFF were primarily distributed throughout spinal cord white matter with some spread into spinal cord gray matter regions. While the localization of spinal cord fMRI signal differences is limited by relatively low spatial resolution (1.25 × 1.25 mm2 in-plane resolution), it appears from our results that regions of greater Mean ALFF in patients may correspond to the spinothalamic tracts and regions of lesser Mean ALFF in patients may correspond to the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Although individual differences in greater ventral and lesser dorsal Mean ALFF were not correlated among patients, the inverse correlation of ventral and dorsal Mean ALFF across patient and control groups suggests that these results may represent an imbalance between pain and sensory processes in fibromyalgia.

The complex mechanisms of local spinal cord modulatory circuits are still being elucidated, however, a shift from inhibition to excitation within the spinal cord dorsal horn could underlie allodynia as demonstrated during peripheral inflammation (40). Such a shift of reduced central inhibition and increased excitation could, in turn, result in increased transmission of nociceptive signals via spinothalamic projection neurons and/or decreased transmission of non-nociceptive signals. Thus, the present findings may relate to altered modulation by local spinal cord circuits in fibromyalgia.

Descending modulation of spinal cord processes could additionally contribute to the present observations. Increased descending facilitation and/or decreased descending inhibition of nociceptive signals, processes of central sensitization (41), could enhance transmission of nociceptive signals to supraspinal regions and/or dampen supraspinal transmission of non-nociceptive signals. Thus, our observations complement previous evidence of altered spinal cord activity during temporal summation of noxious thermal pain in fibromyalgia (17).

Individual differences in Mean ALFF for patients < controls (uncorrected) were strongly positively correlated with symptom measures of fatigue, indicating potential functional and symptomatic implications. While this observation was inverse of the negative association (non-significant) between dorsal Mean ALFF and fatigue across patient and control groups combined, distinct mechanisms may underlie the significant relationship between greater dorsal ALFF and greater reported fatigue within the patient group. For instance, greater dorsal ALFF in patients could be driven by increased descending serotonergic drive (i.e., increased postsynaptic activity) that can inhibit muscle afferents and increase sensations of fatigue (42). Alternatively, increased concentrations of metabolites (e.g., protons, lactate, ATP) in muscle tissue contribute to sensations of non-painful fatigue (43) and could increase transmission and/or input of sensory afferent information. While no significant correlations were observed between sensory testing and Mean ALFF differences, a positive association (trend) of cold pressor test duration and greater dorsal ALFF may suggest that greater baseline sensory input and/or transmission translates to higher endurance of the cold pressor test.

Integrity of Functional Connectivity and Graph Metrics in Fibromyalgia

Similar to the brain, the intrinsic resting state functional networks have been recently investigated in the spinal cord (36). The most reproducible connectivity patterns have included V-V and D-D functional connectivity, which have been termed the bilateral motor and sensory networks, respectively (32–34,36). In addition to functional connectivity between two regions, graph metrics provide a way to summarize the topological properties of a network (for review: (44)), and recently these metrics have been extended to the spinal cord (37). Recently, we demonstrated that unilateral thermal stimulation to the forearm disrupted the bilateral sensory network (D-D functional connectivity) while increasing global efficiency and decreasing modularity of the cervical spinal cord functional network in healthy controls compared to rest (24). As sensory processing is thought to be altered in fibromyalgia, we expected to observe differences in the patterns of functional connectivity in patients compared to control. While we observed evidence of V-V and D-D functional connectivity in both the patients and controls, neither the functional connectivity strength nor the graph metrics differed between the groups. This suggests that these measures were not sensitive to the changes in spinal cord processing accompanying fibromyalgia. The bilaterality of symptoms in the patients contrasts with previous reports of unilateral experimental thermal stimulation in healthy individuals (24,45,46) and may have obscured any group differences in functional connectivity. Thermal stimulation or evoked pressure pain, as used previously in spinal cord (17) and brain (47) fMRI investigations of fibromyalgia, may reveal spinal cord functional network alterations in fibromyalgia. As spinal cord functional connectivity is still a new field, much work is necessary to determine the best methods to study altered sensory processing in clinical conditions including fibromyalgia and chronic pain (34).

Limitations

Precise localization of fMRI results to specific regions and tissues (i.e., gray matter and white matter) of the spinal cord remains challenging due to the current technological limitations of spinal cord fMRI (i.e., spatial resolution). Our spinal cord fMRI sequence was optimized to produce high quality images based on current standards. Additionally, we carefully removed sources of noise as part of our preprocessing pipeline and our results should therefore be minimally affected by motion and physiological signals. Despite these efforts because ALFF is related to the BOLD signal, we cannot rule out the possibility that the location of observed differences in Mean ALFF may be influenced by blood flow directionality in the spinal cord (48). The dynamics of BOLD signal changes (e.g. due to patterns in blood flow, potential artifacts) and its distribution within the spinal cord are currently incompletely understood. We applied robust analysis methods and conservative statistics optimized for brain fMRI; in the future, analysis methods and statistics tailored to the spinal cord may provide more robust results.

We had expected to observe greater low frequency power in patients, particularly in blood-flow rich regions of spinal cord gray matter. However, group differences were located predominantly in regions corresponding to white matter. The specificity of sensory or motor related BOLD signal change in the spinal cord is not consistently restricted to gray matter, as demonstrated in most studies (e.g., (17,49)). For example, motor task activation in the spinal cord encompasses the majority of the ipsilateral hemi-cord (spanning both gray and white matter) and is more focused in the anterolateral quadrant at higher thresholds (23). The neural mechanisms underlying the observed differences in white matter regions remain to be ascertained, however, reliable BOLD signal related activity in white matter (38) and astrocyte (present in gray and white matter) contributions to the BOLD fMRI signal (39) provide support for the validity of these observations.

We did not determine whether our participants had peripheral neuropathy, which alters nociceptive and non-nociceptive afferent input and could contribute to the present observations. While neuropathic pain is distinct from fibromyalgia, signs of peripheral neuropathy occur in a percentage of patients with fibromyalgia (4). In the spinal cord dorsal horn, increased astrocyte activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a rodent model of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (50). Thus, our findings of greater Mean ALFF in the ventral spinal cord may relate to underlying mechanisms of increased spinal cord astrocyte activity and symptoms of allodynia in fibromyalgia. Future investigations involving tests for peripheral neuropathy and combining brain/spinal cord data may clarify the mechanisms underlying our present findings in fibromyalgia.

Lastly, we may have been underpowered to observe significant correlations between individual differences in Mean ALFF and symptom measures of pain (due to high variance). Additionally, physiological effects of medications taken by the patients may have contributed to the observed group differences (e.g., serotonergic mechanisms). Nonetheless, our observed correlation between Mean ALFF and fatigue indicates complex, yet physiological and symptom relevant rs-fMRI signal differences.

Conclusion

The observed alterations in cervical spinal cord activity provide further evidence of altered CNS activity in fibromyalgia. Through replication, validation, and extensions of this research, human cervical spinal cord rs-fMRI may inform future translational discoveries to produce a more complete understanding of spinal cord contributions to fibromyalgia and chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Erin Perrine, Christina Cojocaru, and Elizabeth Cha for assistance with recruitment, data collection, data organization, and data analysis. We also thank Dr. Gary Glover and the Richard M. Lucas Center at Stanford for use of its facilities and staff assistance, and Dr. Christine Law for assistance with piloting the spinal cord fMRI sequence.

Funding Sources: Dr. Martucci, Dr. Weber and Dr. Mackey receive funding from the National Institutes of Health K99 DA040154 (KTM), T32 DA035165 (KAW via SCM), K24 DA029262 (SCM), Redlich Pain Research Endowment.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Other than the cited funding sources, the authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152:S2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper DE, Ichesco E, Schrepf A, Hampson JP, Clauw DJ, Schmidt-Wilcke T, et al. Resting Functional Connectivity of the Periaqueductal Gray Is Associated With Normal Inhibition and Pathological Facilitation in Conditioned Pain Modulation. J Pain 2018;19:635.e1–635.e15.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oaklander AL, Herzog ZD, Downs HM, Klein MM. Objective evidence that small-fiber polyneuropathy underlies some illnesses currently labeled as fibromyalgia. Pain 2013;154:2310–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martucci KT, Mackey SC. Neuroimaging of Pain: Human Evidence and Clinical Relevance of Central Nervous System Processes and Modulation. Anesthesiology 2018;128:1241–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichesco E, Puiu T, Hampson JP, Kairys AE, Clauw DJ, Harte SE, et al. Altered fMRI resting-state connectivity in individuals with fibromyalgia on acute pain stimulation. Eur J Pain 2016;20:1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweinhardt P, Glynn C, Brooks J, McQuay H, Jack T, Chessell I, et al. An fMRI study of cerebral processing of brush-evoked allodynia in neuropathic pain patients. Neuroimage 2006;32:256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baliki MN, Petre B, Torbey S, Herrmann KM, Huang L, Schnitzer TJ, et al. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci 2012;15:1117–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kutch JJ, Labus JS, Harris RE, Martucci KT, Farmer MA, Fenske S, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity predicts longitudinal pain symptom change in urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a MAPP network study. Pain 2017;158:1069–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martucci KT, Shirer WR, Bagarinao E, Johnson KA, Farmer MA, Labus JS, et al. The posterior medial cortex in urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: detachment from default mode network-a resting-state study from the MAPP Research Network. Pain 2015;156:1755–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kucyi A, Moayedi M, Weissman-Fogel I, Goldberg MB, Freeman BV, Tenenbaum HC, et al. Enhanced medial prefrontal-default mode network functional connectivity in chronic pain and its association with pain rumination. J Neurosci 2014;34:3969–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alshelh Z, Di Pietro F, Youssef AM, Reeves JM, Macey PM, Vickers ER, et al. Chronic Neuropathic Pain: It’s about the Rhythm. J Neurosci 2016;36:1008–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilpatrick LA, Kutch JJ, Tillisch K, Naliboff BD, Labus JS, Jiang Z, et al. Alterations in resting state oscillations and connectivity in sensory and motor networks in women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol 2014;192:947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J-Y, Kim S-H, Seo J, Kim S-H, Han SW, Nam EJ, et al. Increased power spectral density in resting-state pain-related brain networks in fibromyalgia. Pain 2013;154:1792–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desmeules JA, Cedraschi C, Rapiti E, Baumgartner E, Finckh A, Cohen P, et al. Neurophysiologic evidence for a central sensitization in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1420–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen KB, Loitoile R, Kosek E, Petzke F, Carville S, Fransson P, et al. Patients with fibromyalgia display less functional connectivity in the brain’s pain inhibitory network. Mol Pain 2012;8:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosma RL, Mojarad EA, Leung L, Pukall C, Staud R, Stroman PW. FMRI of spinal and supra-spinal correlates of temporal pain summation in fibromyalgia patients. Hum Brain Mapp 2016;37:1349–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zang Y-F, He Y, Zhu C-Z, Cao Q-J, Sui M-Q, Liang M, et al. Altered baseline brain activity in children with ADHD revealed by resting-state functional MRI. Brain Dev 2007;29:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RS, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1113–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon EA, Benham G, Sturgeon JA, Mackey S, Johnson KA, Younger J. Development of the Sensory Hypersensitivity Scale (SHS): a self-report tool for assessing sensitivity to sensory stimuli. J Behav Med 2016;39:537–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broderick JE, DeWitt EM, Rothrock N, Crane PK, Forrest CB. Advances in Patient-Reported Outcomes: The NIH PROMIS(®) Measures. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2013;1:1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain 2004;20:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber KA 2nd, Chen Y, Wang X, Kahnt T, Parrish TB. Lateralization of cervical spinal cord activity during an isometric upper extremity motor task with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 2016;125:233–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber KA 2nd, Sentis AI, Bernadel-Huey ON, Chen Y, Wang X, Parrish TB, et al. Thermal Stimulation Alters Cervical Spinal Cord Functional Connectivity in Humans. Neuroscience 2018;369:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Leener B, Lévy S, Dupont SM, Fonov VS, Stikov N, Louis Collins D, et al. SCT: Spinal Cord Toolbox, an open-source software for processing spinal cord MRI data. Neuroimage 2017;145:24–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuo X-N, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, et al. The oscillating brain: complex and reliable. Neuroimage 2010;49:1432–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Qian W, Jin R, Li X, Luk KD, Wu EX, et al. Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF) in the Cervical Spinal Cord with Stenosis: A Resting State fMRI Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: A MATLAB Toolbox for “Pipeline” Data Analysis of Resting-State fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci 2010;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penttonen M, Buzsáki G. Natural logarithmic relationship between brain oscillators. Thalamus Relat Syst 2003;2:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 2009;44:83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barry RL, Rogers BP, Conrad BN, Smith SA, Gore JC. Reproducibility of resting state spinal cord networks in healthy volunteers at 7 Tesla. Neuroimage 2016;133:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry RL, Smith SA, Dula AN, Gore JC. Resting state functional connectivity in the human spinal cord. Elife 2014;3:e02812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eippert F, Kong Y, Winkler AM, Andersson JL, Finsterbusch J, Buchel C, et al. Investigating resting-state functional connectivity in the cervical spinal cord at 3T. Neuroimage 2017;147:589–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen LM, Mishra A, Yang P-F, Wang F, Gore JC. Injury alters intrinsic functional connectivity within the primate spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:5991–5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong Y, Eippert F, Beckmann CF, Andersson J, Finsterbusch J, Büchel C, et al. Intrinsically organized resting state networks in the human spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:18067–18072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Zhou F, Li X, Qian W, Cui J, Zhou IY, et al. Organization of the intrinsic functional network in the cervical spinal cord: A resting state functional MRI study. Neuroscience 2016;336:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding Z, Huang Y, Bailey SK, Gao Y, Cutting LE, Rogers BP, et al. Detection of synchronous brain activity in white matter tracts at rest and under functional loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang M, He Y, Sejnowski TJ, Yu X. Brain-state dependent astrocytic Ca2+ signals are coupled to both positive and negative BOLD-fMRI signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E1647–E1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takazawa T, Choudhury P, Tong C-K, Conway CM, Scherrer G, Flood PD, et al. Inhibition Mediated by Glycinergic and GABAergic Receptors on Excitatory Neurons in Mouse Superficial Dorsal Horn Is Location-Specific but Modified by Inflammation. J Neurosci 2017;37:2336–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.François A, Low SA, Sypek EI, Christensen AJ, Sotoudeh C, Beier KT, et al. A Brainstem-Spinal Cord Inhibitory Circuit for Mechanical Pain Modulation by GABA and Enkephalins. Neuron 2017;93:822–839.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor JL, Amann M, Duchateau J, Meeusen R, Rice CL. Neural Contributions to Muscle Fatigue: From the Brain to the Muscle and Back Again. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48:2294–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollak KA, Swenson JD, Vanhaitsma TA, Hughen RW, Jo D, White AT, et al. Exogenously applied muscle metabolites synergistically evoke sensations of muscle fatigue and pain in human subjects. Exp Physiol 2014;99:368–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nash P, Wiley K, Brown J, Shinaman R, Ludlow D, Sawyer AM, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging identifies somatotopic organization of nociception in the human spinal cord. Pain 2013;154:776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cahill CM, Stroman PW. Mapping of neural activity produced by thermal pain in the healthy human spinal cord and brain stem: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Magn Reson Imaging 2011;29:342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez-Sola M, Woo CW, Pujol J, Deus J, Harrison BJ, Monfort J, et al. Towards a neurophysiological signature for fibromyalgia. Pain 2017;158:34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giove F, Garreffa G, Giulietti G, Mangia S, Colonnese C, Maraviglia B. Issues about the fMRI of the human spinal cord. Magn Reson Imaging 2004;22:1505–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber KA 2nd, Chen Y, Wang X, Kahnt T, Parrish TB. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spinal cord during thermal stimulation across consecutive runs. Neuroimage 2016;143:267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ji X-T, Qian N-S, Zhang T, Li J-M, Li X-K, Wang P, et al. Spinal astrocytic activation contributes to mechanical allodynia in a rat chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain model. PLoS One 2013;8:e60733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.