Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate the morbidity of subthreshold pediatric bipolar (BP) disorder.

Methods:

We performed a systematic literature search in November 2017 and included studies examining the morbidity of pediatric subthreshold BP. Extracted outcomes included functional impairment, severity of mood symptoms, psychiatric comorbidities, suicidal ideation and behaviors, and mental health treatment. We used meta-analysis to compute the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous measures and the pooled risk ratio (RR) for binary measures between two paired groups: subthreshold pediatric BP vs. controls, and subthreshold pediatric BP vs. pediatric BP-I.

Results:

Eleven papers, consisting of seven datasets, were included. We compared subthreshold pediatric BP (N=244) to non-Bipolar controls (N=1125) and subthreshold pediatric BP (N=643) to pediatric BP-I (N=942). Subthreshold pediatric BP was associated with greater functional impairment (SMD=0.61, CI 0.25–0.97), greater severity of mood symptomatology (mania: SMD=1.88, CI 1.38–2.38; depression: SMD=0.66, CI 0.52–0.80), higher rates of disruptive behavior (RR=1.75, CI 1.17–2.62), mood (RR=1.78, CI 1.29–2.79) and substance use (RR=2.27, CI 1.23–4.21) disorders, and higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (RR=7.66, CI 1.71–34.33) compared to controls. Pediatric BP-I was associated with greater functional impairment, greater severity of manic symptoms, higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts, and higher rates of mental health treatment compared to subthreshold pediatric BP. There were no differences between full and subthreshold cases in the severity of depressive symptoms or rates of comorbid disorders.

Conclusions:

Subthreshold pediatric BP disorder is an identifiable morbid condition associated with significant functional impairment including psychiatric comorbidities and high rates of suicidality.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, pediatric, subthreshold, child

Introduction

Because pediatric bipolar (BP) disorder tends to evolve over time, some youth may present to clinical attention with insufficient symptoms to fulfill full diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis of BP disorder. However, while much is known about full threshold pediatric BP disorder, little is known about subthreshold forms of pediatric BP disorder.

The importance of subthreshold psychiatric diagnoses has been widely recognized in adult psychiatry. A survey of 2406 adults followed up for 18 months documented that subthreshold adult psychiatric symptoms predicted functional disability at follow up. The authors of this study concluded that “the importance of subthreshold symptoms should not be underestimated”1. Other authors have argued that a ‘mood spectrum model’ is important in identifying individuals with severe psychopathology not adequately attended to in the DSM 52. Yet, uncertainties remain as to whether subthreshold BP disorder in children is a meaningful clinical entity.

Whether subthreshold forms of pediatric BP disorder represent a meaningful clinical entity associated with morbidity and dysfunction has important clinical, scientific and public health relevance. If subthreshold pediatric BP disorder is found to be morbid, clinicians should consider identifying and treating such patients. Such interventions may mitigate the progression of the disorder to a full syndromatic state. Scientifically, such information can allow the identification of neurobiological precursors to pediatric BP disorder before the confounders of chronicity and treatment makes interpretation of findings difficult. From the public health perspective, this information can lead to the improved efforts aimed at screening children at risk for BP disorder in the primary care setting and the development of early intervention strategies aimed at mitigating the progression of the disorder to its fullest morbidity.

The main aim of the present study was to examine what is known about the morbidity of subthreshold pediatric BP disorder. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the extant literature on the subject and subjected the data to a qualitative analysis and meta-analysis. We hypothesized that subthreshold pediatric BP disorder would be prevalent and morbid. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis on subthreshold pediatric BP disorder.

Methods

Literature Review

We performed a literature search through PubMed in November 2017 utilizing the following search algorithm: (sub threshold or subthreshold or subsyndromal) AND (depression or mania or mood or mood disorder or bipolar disorder or bipolar or depressive or hypomania or cyclothymia) AND (child or children or youth or adolescent or teen or pediatric). In addition, references in the identified papers were reviewed and added if applicable to the search criteria. Reference lists of retrieved papers were screened, and papers that possibly met inclusion criteria were retrieved and studied.

Selection Criteria

We included only original studies that specifically evaluated subthreshold pediatric BP disorder. We implemented the following inclusion criteria: (1) original research; (2) uses operational definition of subthreshold bipolar symptoms; (3) subjects are limited to youth samples (≤ 18 years); 4) functional outcomes were assessed and results reported; (5) articles were written in English. Articles were excluded if (1) they were reviews or opinions or (2) the study was not available in English or accessible through PubMed. Two psychiatrists and a research assistant screened all the articles for relevance by examining the abstracts and identifying the relevant articles in full text to evaluate their eligibility.

Data Extraction

The following variables were extracted from the manuscripts: study sample, mean age of probands, the percentage of male probands, the source of probands (community or clinic), type of controls (psychiatric versus non mentally ill), length of follow up in years (for longitudinal studies), and outcomes related to subthreshold BP disorder morbidity, including assessment of functioning, severity of mood symptoms, psychiatric comorbidities, suicidal ideation and associated behaviors, and utilization of mental health services.

Analytic approach

Five correlates of illness morbidity were examined: 1) functional impairment; 2) mood symptomatology; 3) psychiatric comorbidity; 4) suicidality and 5) utilization of mental health services. For each of these domains, we used meta-analysis to compute the pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous measures and the pooled risk ratio (RR) for binary measures between two pairs of groups: subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder vs. non-Bipolar controls, and subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder vs. those with full threshold pediatric BP-I disorder. Because pediatric BP-I disorder has a higher prevalence and is associated with greater morbidity than pediatric BP-II disorder, we did not utilize pediatric BP-II as a comparison group. All of the meta-analyses used the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird3, which computes pooled SMDs and RRs weighted by sample size. All analyses were implemented in STATA 14.04.

Results

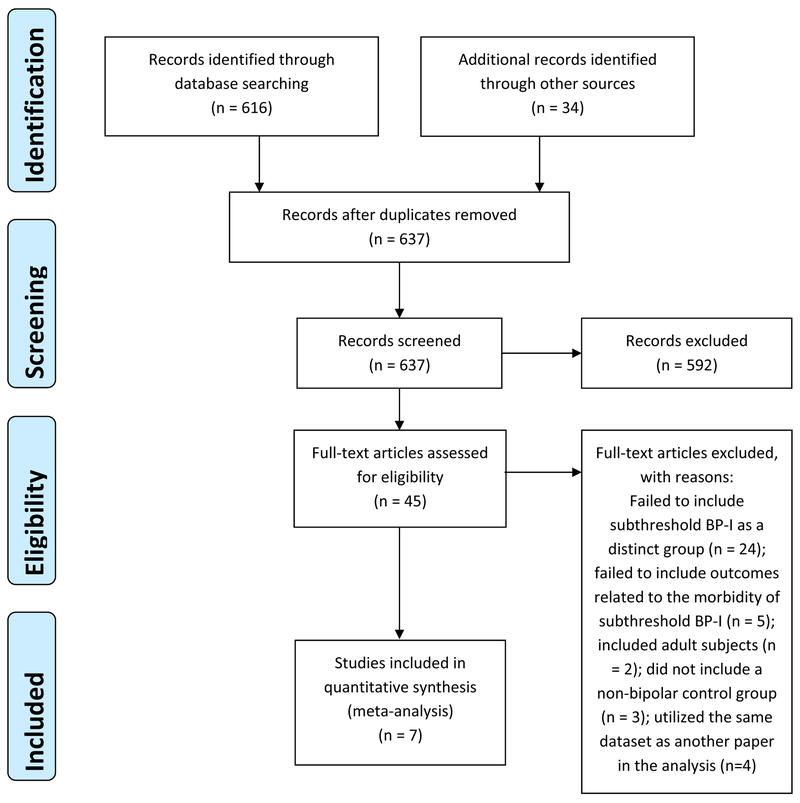

As shown in The Prisma Chart (Figure 1), the literature search identified 45 articles considered relevant and these were carefully examined. Of these 45, only 11 articles met all our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Excluded were studies that either 1) failed to include subthreshold BP disorder as a distinct group with an operationalized criteria for diagnosis (N=24), 2) failed to include outcomes related to the morbidity of subthreshold BP disorder (N=5), 3) included adult subjects (N=2) or 4) did not include either a Bipolar I control group or a non-Bipolar control group (N=3).

Figure 1:

PRISMA diagram

The 11 papers identified included a total of 7 datasets usable for meta-analysis.5–8,9,10,11,12,13 Five of the papers identified reported data from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP) and data were taken from the most recent publication from this group. Two of the papers identified presented data from the Course and Outcomes of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study, but were included as separate entries because one study included cross-sectional data and the other included longitudinal data. Of the 7 datasets included in the meta-analysis, four were cross-sectional, one was longitudinal, and two contained both cross-sectional and longitudinal results. Our meta-analysis compared subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder to non-Bipolar controls, and a separate analysis was conducted comparing subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder and those with full threshold pediatric BP-I disorder. Table 1 gives the characteristics of each study, number of subjects, age of subjects, each study’s operational criteria for diagnosing subthreshold BP disorder and the main findings of each paper. Table 1 also includes information about two studies that did not meet our inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis, but did have findings relevant to this paper and were therefore included in our qualitative review.

Table 1:

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis and the qualitative review, including study-specific definitions of subthreshold BP disorder and main findings of each study.

| Author | Number of subjects | Sample | Type of study | Meta-Analysis Comparisons | Mean age* (years) | Percent Male* | Criteria for diagnosing SubBP | Main findings of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included in meta-analysis | ||||||||

| Lewinsohn et al. 20028 | SubBP N = 48; BP-I N = 17; Non mentally ill controls N = 307 | Community | Longitudinal and cross-sectional | SubBP vs BP-I; SubBP vs Controls | 16.6 | 46.8 (N=175) | One manic core symptom (DSM-IV criterion A) plus one or more other manic symptoms (DSM-IV criterion B). | Youth with BP-I and SubBP had more impaired functioning, and higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and suicidality vs. controls. |

| Findling et al. 20059 | SubBP N = 58; BP-I N = 65; Non-bipolar controls N = 44 | Clinical | Cross-sectional | SubBP vs BP-I; SubBP vs Controls | 11.3 | 53.9 (N=99) | Spontaneous, dysfunctional mood episodes that did not meet full criteria for any other mood disorder. | Youth with SubBP had greater impairment in functioning and more substantial mood symptomatology vs. controls. |

| Axelson et al. 200610 | SubBP N = 153; BP-I N = 255 | Clinical | Cross-sectional | SubBP vs BP-I | 12.7 | 53.2 (N=217) | Elated mood plus 2 associated DSM-IV symptoms or irritable mood plus 3 DSM-IV associated symptoms, along with a change in level of functioning, for a minimum of 4 hours, and at least 4 cumulative lifetime days meeting the criteria. | No differences between SubBP and BP-I subjects on lifetime rates of comorbid diagnosis, suicidal ideation, or major depression. |

| Birmaher et al. 200911 | SubBP N = 141; BP-I N = 244 | Clinical | Longitudinal | SubBP vs BP-I | 12.6 | 54.3 (N=209) | Elated mood plus 2 associated DSM-IV symptoms or irritable mood plus 3 DSM-IV associated symptoms, along with a change in level of functioning, for a minimum of 4 hours, and at least 4 cumulative lifetime days meeting the criteria. | Thirty eight percent of children with SubBP converted to BP-I or BP-II over the course of 4 years of follow up. SubBP was associated with less likelihood of full recovery following the index mood episode compared with BP-I and BP-II. |

| Demeter et al. 20135 | SubBP N = 155; BP-I N = 290 | Clinical | Cross-sectional | SubBP vs BP-I | 10.5 | 63 (N=339) | Children and adolescents who met criteria for cyclothymia or Bipolar Disorder NOS as defined in DSM IV. | Subjects with BP-I had worse functioning and more severe symptoms of mania than subjects with SubBP. |

| Hafeman et al. 20136 | SubBP N = 88; BP-I N = 71; Psychiatric Controls N = 545 | Clinical | Cross-sectional | SubBP vs BP-I; SubBP vs Controls | 9.4 | 67.8 (N=477) | Elated mood plus 2 associated DSM-IV symptoms or irritable mood plus 3 DSM-IV associated symptoms, along with a change in level of functioning, for a minimum of 4 hours, and at least 4 cumulative lifetime days meeting the criteria. | There were no differences in level of impairment or mood severity between SubBP and BP-I, but both groups had worse functioning, greater mood symptomatology, and a higher rate of conduct disorder compared to psychiatric controls. |

| Paaren et al. 20137 | SubBP N = 50; Controls (negative screening for mania/ hypomania and depression) N = 229 | Community | Longitudinal and cross-sectional | SubBP vs Controls | 16.5 | 30 (N=27) | Youth who met criteria for one of the following: Brief-episode hypomania: criteria for hypomania were fulfilled but for less than 4 days; Subsyndromal hypomania: 1 or 2 main symptoms and 1–2 additional symptoms were fulfilled (total 3 or more symptoms), no specific duration defined. | Youth with hypomania spectrum illnesses had high rates of comorbid depression, had equal rates of suicidality when compared with subjects with MDD, and were more likely than controls to seek out mental health treatment. Fifty to sixty percent of youth with subthreshold hypomania continued to experience depressive episodes in adulthood but had low rates of conversion to BP-I (0 to 4%). |

| Not included in meta-analysis | ||||||||

| Stringaris et al. 201012 | SubBP N = 58 (based on parent report) and 48 (based on youth report) | Clinical and Community | Longitudinal | N/A | 12.8 (parent report); 13.7 (youth report) | 64 (parent report); 42 (youth report) | Youth with periods of elated or expansive mood, accompanied by at least 3 DSM-IV B criteria, the episode causes impairment and lasts more than 1 hour and less than 4 days. Could meet criteria based on parent report or youth report. | SubBP was associated with social impairment, DBDs and ADHD. |

| Zimmerman et al. 2000913 | SubBP N = 202; BP-I N = 65; MDD N = 286; Controls N = 1273 | Community | Longitudinal | N/A | 19 (age range 14–24) | 51.4 (N=1135) | Youth met criteria for MDD and either had 4+ days of elated/expansive mood without meeting DSM-IV criteria B, or had unusually irritable mood and 3 other manic symptoms, but symptoms were not observable by others. | SubBP was associated with family history of mania, higher rates of panic disorder and nicotine and alcohol use disorders, and higher rates of criminal acts when compared to MDD. SubBP also converted more often into BP-I at follow up. |

SubBP = Subthreshold Bipolar disorder; BP-I = Bipolar Disorder type I; BP-II = Bipolar Disorder type II; DBDs = Disruptive Behavior Disorders; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder.

Mean age, percent male, and total number male are data listed for the entire study population of the paper.

Using the available data, we first compared subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder to non-Bipolar pediatric controls using data from four available studies. Two of these studies were cross-sectional and two included both longitudinal and cross-sectional data. Two of these studies utilized a clinical sample and two community samples. One of the studies used a non-mentally ill control group, one used a control group consisting of subjects with no symptoms of depression or (hypo)mania, and two studies used a non-Bipolar psychiatric control group. This analysis included a total of 244 subjects with subthreshold BP disorder and 1125 non-Bipolar controls. Secondly, we compared subjects with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder to subjects with full threshold pediatric BP- I disorder using data from six studies. Four of these studies presented cross-sectional data, one presented longitudinal data, and one presented both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. This analysis included a total of 643 subjects with subthreshold BP disorder and 942 subjects with BP- I disorder. Five of these studies used a clinical sample and one a community sample.

Meta-Analysis Results:

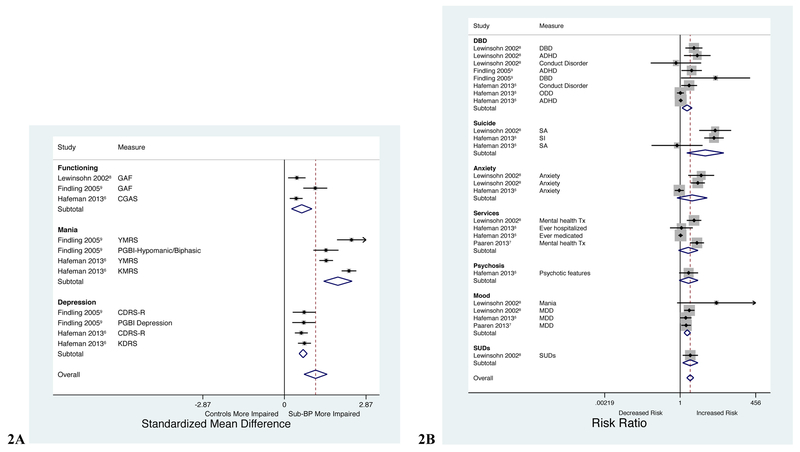

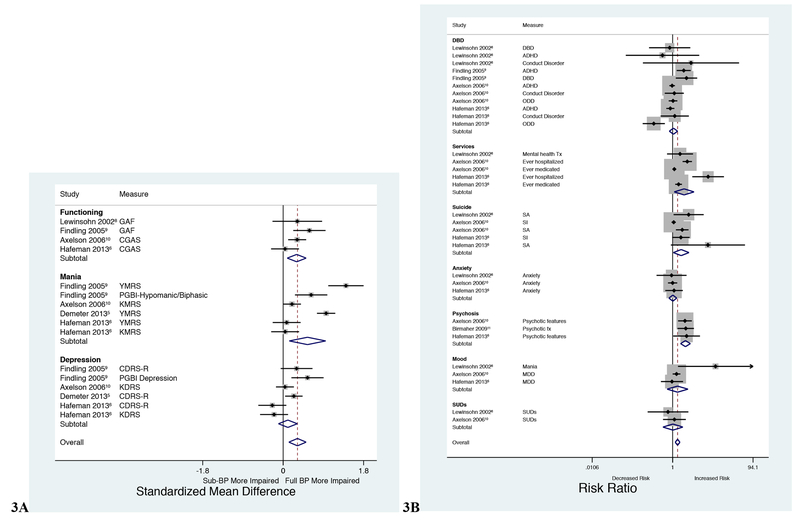

Our meta-analysis addressed five relevant areas 1) functional impairment; 2) mood symptomatology; 3) psychiatric comorbidity; 4) suicidality; and 5) utilization of mental health services (Figures 2–3):

Figure 2A:

Comparison of level of functioning and severity of mood symptoms in youth with subthreshold BP disorder vs controls. GAF = Global Assessment of Functioning; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; PGBI = Parent General Behavior Inventory; KMRS = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders (KSADS) Mania Rating Scale; CDRS-R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised; KDRS = KSADS Depression Rating Scale.

Figure 2B: Comparison of comorbid psychiatric disorders, suicidality, and utilization of mental health services in youth with subthreshold BP vs controls. DBD = Disruptive behavior disorders; ADHD = Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ODD = Oppositional defiant disorder; SA = Suicide attempts; SI = Suicidal ideation; Tx = Treatment; MDD = Major depressive disorder; SUDs = Substance use disorders.

Figure 3A:

Comparison of level of functioning and severity of mood symptoms in youth with subthreshold BP disorder vs full threshold BP-I disorder. Figure 3B: Comparison of comorbid psychiatric disorders, suicidality, and utilization of mental health services in youth with subthreshold BP disorder vs full threshold BP-I disorder.

1. Functional Impairment

The meta-analysis showed that children with subthreshold BP disorder had significantly worse current functioning than non-Bipolar controls (SMD 0.608, 95% CI 0.248–0.967; p = 0.001). It also showed that full threshold BP-I disorder was associated with worse current functioning than subthreshold BP disorder (SMD 0.303, 95% CI 0.091–0.515; p = 0.005).

2. Severity of mood symptomatology

The meta-analysis found significant differences between subthreshold BP disorder and non-Bipolar controls on current symptoms of both mania and depression (mania: SMD = 1.879, 95% CI 1.380–2.378; p < 0.001; depression: SMD = 0.658, 95% CI 0.517–0.798; p < 0.001). The meta-analysis also showed that while full threshold BP-I disorder was associated with more current symptoms of mania (SMD = 0.545, 95% CI 0.137–0.953; p = 0.009), there were no significant differences between full and subthreshold BP disorder when comparing current symptoms of depression (SMD = 0.106, 95% CI −0.105–0.317; p = 0.326).

3. Psychiatric comorbidity

The meta-analysis comparing children with subthreshold BP disorder to non-Bipolar controls showed significantly higher rates of lifetime disruptive behavior (DBDs) (z = 2.70, RR = 1.748, 95% CI 1.165–2.622; p = 0.007), mood (z = 4.42, RR = 1.778, 95% CI 1.377–2.295; p < 0.001) and substance use disorders (SUDs) (z = 2.60, RR = 2.269, 95% CI 1.225–4.206; p = 0.009) in the subthreshold BP group. The meta-analysis comparing subthreshold BP disorder to full threshold BP-I disorder showed only a significant difference in the lifetime rate of psychosis (z = 5.13, RR = 2.006, 95% CI 1.565–2.726; p < 0.001), which was higher in the full threshold BP-I group, but no significant differences in the rate of other disorders. See Table 2 for the reported prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in subthreshold BP disorder.

Table 2:

Summary of the reported prevalence of comorbid disorders in subthreshold BP.

| Lewisohn et al. 20028 | Findling et al. 20059 | Axelson et al. 200610 | Birmaher et al. 200911 | Hafeman et al. 20136 | Paaren et al. 20137 | Stringaris et al. 201012 | Zimmerman et al. 200913 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | SubBP N = 48; BP-I N = 17; Non mentally ill controls N = 307 | SubBP N = 58; BP-I N = 65; Psychiatric Controls N = 44 | SubBP N = 153; BP-I N = 255 | SubBP N = 141; BP-I N = 244 | SubBP N = 88; BP-I N = 71; Psychiatric Controls N = 545 | SubBP N = 50; Psychiatric Controls N = 229 | SubBP N = 58 (based on parent report) and 48 (based on youth report) | SubBP N = 202; BP-I N = 65; Controls N = 1273 |

| Anxiety | BP-I: 32.0% SubBP: 33.3% Controls: 7.7% |

-- | BP-I: 37.3% SubBP: 37.9% |

-- | BP-I: 29.6% SubBP: 27.3% Controls: 29.4% |

-- | SubBP (parent report): 9% SubBP (youth report): 4% |

BP-I: 55.4% SubBP: 53% Controls: 19.6% |

| DBDs | BP-I: 18.6% SubBP: 22.2% Controls: 6.9% |

BP-I: 43% SubBP: 34.5% Controls: 0% |

-- | -- | -- | -- | SubBP (parent report): 50% SubBP (youth report): 22% |

-- |

| ADHD | BP-I: 8.2% SubBP: 11.1% Controls: 2.7% |

BP-I: 66.1% SubBP: 63.8% Controls: 15.9% |

BP-I: 60.4% SubBP: 62.1% |

-- | BP-I: 62% SubBP: 70.4% Controls: 66.6% |

-- | SubBP (parent report): 29% SubBP (youth report): 6% |

-- |

| CD | BP-I: 8.2% SubBP: 3.0% Controls: 3.0% |

-- | BP-I: 13.3% SubBP: 11.8% |

-- | BP-I: 14.1% SubBP: 12.5% Controls: 6.1% |

-- | -- | -- |

| ODD | -- | -- | BP-I: 40.8% SubBP: 40.5% |

-- | BP-I: 14.1% SubBP: 40.9% Controls: 39.1% |

-- | -- | -- |

| SUDs | BP-I: 22.2% SubBP: 23.7% Controls: 10.4% |

-- | BP-I: 9.8% SubBP: 8.5% |

-- | -- | -- | -- | BP-I: 70.7% SubBP: 56.5% Controls: 41.7% |

| MDD | SubBP: 40.9% Controls: 18.9% |

-- | BP-I: 53.3% SubBP: 42.5% |

-- | BP-I: 19.7% SubBP: 20.4% Controls: 13% |

SubBP: 46% Controls: 30% |

SubBP (parent report): 4% SubBP (youth report): 4% |

-- |

| Psychosis | -- | -- | BP-I: 34.5% SubBP: 17.6% |

BP-I: 28.3% SubBP: 13.5% |

BP-I: 22.5% SubBP: 10.2% Controls: 4.6% |

-- | -- | -- |

DBDs = Disruptive behavior disorders; ADHD = Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CD = Conduct disorder; ODD = Oppositional defiant disorder; SUDs = Substance use disorders; MDD = Major depressive disorder.

4. Suicidality

Our meta-analysis found significantly higher lifetime rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in children with subthreshold BP disorder than in non-Bipolar controls (z = 2.66, RR = 7.656, 95% CI 1.707–34.334; p = 0.008), and also found significantly higher lifetime rates of suicidal ideation and attempts in children with full BP-I disorder compared to children with subthreshold BP disorder (z = 2.15, RR = 1.621, 95% CI 1.043–2.519; p = 0.032).

5. Utilization of mental health services

Our meta-analysis showed no significant difference in the lifetime utilization of mental health services between children with subthreshold BP disorder and non-Bipolar controls (z = 1.63, RR = 1.928, 95% CI 0.875–4.249, p = 0.103) but did show higher lifetime rates of mental health service utilization in children with full BP-I disorder compared to those with subthreshold BP disorder (z = 2.27, RR = 1.914, 95% CI 1.094–3.350, p = 0.023).

Discussion

Our systematic review of the extant literature and meta-analysis evaluating the morbidity associated with subthreshold BP disorder in youth showed consistently that subthreshold BP disorder is highly morbid with high rates of psychiatric comorbidity, functional impairment, and suicidality. It also showed that full threshold pediatric BP-I disorder was associated with greater morbidity and dysfunction than subthreshold BP-I in some areas, but the two groups had similar outcomes in other areas. These results confirm our study hypothesis that subthreshold pediatric BP disorder is a highly morbid clinical entity worthy of further clinical and scientific attention.

Our meta-analysis shows consistently that children with subthreshold BP disorder were significantly more impaired than non-Bipolar controls in multiple non-overlapping measures of functioning including high rates of symptoms of mania and depression, high rates of comorbid disruptive behavior, mood and substance use disorders, high rates of suicidality, and impaired scores on scales assessing overall functioning. These findings are particularly noteworthy considering that 3 out of 4 of the available studies used in this meta-analysis relied on non-bipolar psychiatric controls, as opposed to healthy controls.

While our meta-analysis showed that youth with full threshold pediatric BP-I disorder were more impaired than those with a subthreshold diagnosis, were more likely to have suicidal ideation or attempts, and were more likely to utilize mental health services, it is noteworthy that results also showed that children with subthreshold BP disorder did not significantly differ from full threshold BP-I disorder cases in terms of degree of depressive symptoms, or rates of comorbid disruptive behavior, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.

Also noteworthy are the findings from several studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis due to insufficient information. These studies also reported that pediatric subthreshold BP disorder was associated with high levels of morbidity and dysfunction. For example, Stringaris et al. 201012 found that pediatric BP disorder not otherwise specified (BP-NOS) was associated with social impairment, DBDs and ADHD. Likewise, Zimmerman et al. 200913 found that adolescents and young adults with subthreshold BP disorder had higher rates of criminal acts and higher rates of substance use disorders than subjects with MDD. Taken together, these findings further support the high morbidity and dysfunction associated with subthreshold pediatric BP disorder.

Some critics have vigorously criticized the usefulness of subthreshold diagnoses in general and that of subthreshold pediatric BP disorder in particular, with the argument that it is too imprecise, and that its use may expand the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in general and lead to the use off-label treatments.14,15 Despite such criticism, this meta-analysis has shown that children with subthreshold BP disorder are highly impaired relative to children with other psychiatric disorders and certainly when compared with healthy children. In some areas, they are as impaired as children with full threshold BP-I disorder. Considering the high prevalence of subthreshold forms of pediatric BP disorder, estimated to afflict up to 6% of youth16,17,18, and its severe morbidity, attending to such children has very large clinical and public health implications. Clinicians interfacing with patients that have symptoms of, but don’t reach diagnostic threshold for, BP-I disorder should be informed about their morbidity and disability to ensure that they receive the appropriate clinical attention and ongoing clinical care. Youth with subthreshold forms of pediatric BP disorder can benefit from inclusion in clinical trials to provide the field with adequate efficacy and safety data to guide the clinical community. This need was recently highlighted by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force, which called for increased research into preventative strategies, including both the prevention of BP disorder, and the prevention of the functional impairment and comorbidities associated with the condition19.

In addition to the morbidity of subthreshold BP disorder, it should be noted that children with subthreshold BP disorder have a high rate of conversion to full BP disorder, with some longitudinal studies citing rates of conversion at close to or greater than 50%20,21. Children with subthreshold BP disorder have been shown to have similar rates of familial BP-I disorder when compared to children with full BP-I disorder, and higher rates of familial BP-I disorder than children with ADHD or controls, suggesting a diagnostic continuity between subthreshold BP disorder and full threshold BP disorder22. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish if these two diagnostic groups are discrete entities, or represent one disorder with multiple contributing genetic and environmental factors leading to a pleomorphic presentation with variable symptomatic expression that may be above or below arbitrary thresholds set forth by our nosology. The concept of the bipolar spectrum, with worsening morbidity, including mood symptoms, suicide attempts, psychiatric comorbidities, and the need for mental health treatment, from subthreshold BP to BP-II to BP-I, has also been demonstrated in adult psychiatry research23. Considering the severe morbidity associated with full threshold BP-I disorder, intervening at the level of subthreshold manifestations of this illness may mitigate the progression of the disorder to its most severe outcomes, again reinforcing the importance of accurately identifying children with this condition.

Our findings should be considered in light of a few limitations. The number of available data sets was relatively small, and not all of these data sets included each outcome of interest. Although we found a few additional relevant studies, we could not include them to the meta-analysis since they did not use an operational definition of subthreshold BP-I disorder, did not include a full threshold BP-I disorder or non-bipolar comparison group, or contained adult subjects. We only utilized one database to perform our literature search. Although PubMed is thought to be the most comprehensive database, it is possible that we did not identify all potential papers that could have been included in this review. Furthermore, we did not utilize a protocol to perform this meta-analysis, and did not perform a systematic review of each paper for biases, which may increase the risk of bias in our findings. Bipolar disorder type II was not included in this review, or in the meta-analysis, and further comparison of pediatric subthreshold BP disorder with Bipolar disorder type II should be included in future studies.

All studies included in this meta-analysis used defined, operationalized criteria for subthreshold BP disorder. However, not all of these criteria were the same, ranging from criteria consistent with BP-NOS as defined by DSM-IV, to only requiring 2 symptoms of mania. In addition, the timeframe of the symptoms varies between studies and is not defined in some of the papers as a criterion for diagnosis, while other studies only require the symptoms be present for hours. One of the fundamentally important aspects of diagnosing Bipolar Disorder according to DSM criteria is that it is characterized by periods of abnormal mood and behavior that are distinguishable from a person’s baseline. It could be argued that having only a few symptoms of mania for a period of several hours may represent normal fluctuations in mood, rather than an underlying subthreshold mood disorder. Furthermore, the presence of depressive episodes was not a criterion for inclusion into the subthreshold BP group. Studies have examined whether subjects with mania alone are as impaired as subjects with both mania and depression. De Crescenzo et al.24 found that children and adolescents with both mania and depression were significantly more likely to have a suicide attempt than subjects with mania only, while Merikangas et al.25 found that adolescents with mania only were equally as impaired as adolescents with mania and depression in most areas. However, if the threshold for inclusion into the subthreshold BP group was too low, and participants in the group were not psychiatrically ill, then we would not have expected the subthreshold BP group to differ so significantly from the control group on our outcome measures. It could be argued that the subthreshold BP group did have a high rate of comorbid psychiatric disorders (see Table 2), and that could be the reason that the morbidity of the group was so high. The majority of our controls were psychiatric controls, which we would expect to reduce this possibility; however, one of our datasets did include a control group that did not carry any psychiatric diagnoses. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the heterogeneity of the subthreshold BP group and the control group influenced our findings.

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) is a new diagnosis in child psychiatry, introduced in DSM 5 in 201326. Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is characterized by chronic irritability and temper outbursts. This diagnosis was developed due to concerns that youth with chronic irritability were being misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder27,28. The articles utilized in our meta-analysis were written during the time frame when it was felt pediatric bipolar disorder was being over diagnosed. This may lead to questions as to whether the subjects included in this meta-analysis truly had pediatric subthreshold BP disorder or would have been more appropriately diagnosed with DMDD. Although a patient cannot have both BP disorder and DMDD per DSM-5, studies looking at the overlap of pediatric BP disorder and DMDD have found that approximately 25% of children with BP disorder also meet criteria for DMDD29, while another study found that approximately 17% of pediatric patients “at risk” of being diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder due to parent-reported manic symptoms upon admission to an inpatient unit ultimately met criteria for DMDD based on parent report and inpatient observation30. However, children with BP disorder who meet criteria for DMDD are not more likely to have BP-NOS compared with another BP subtype (BP-I or BP-II)29, suggesting that the diagnosis of BP-NOS is not necessarily synonymous with DMDD. In this paper, we only included studies that used operationalized criteria for the diagnosis of subthreshold BP disorder, which included the presence of distinct mood episodes that did not meet full criteria for mania or hypomania, as opposed to the presence of chronic mood symptoms or temper outbursts. The findings from this study are meant to represent a population of subjects who are on the bipolar spectrum, as opposed to encompassing all youth who have mood disorders that don’t meet criteria for MDD or full BP disorder. Nevertheless, it is possible that at least some of the children included in this meta-analysis would meet criteria for both BP-NOS and DMDD. Children who meet criteria for both BP disorder and DMDD are more likely to be more significantly impaired than children who meet criteria for BP alone29, while children who meet criteria for DMDD are equally as impaired as children with BP-NOS28. Children with DMDD are likely to have other psychiatric comorbidities, including ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder28, 30, 31. Therefore, current research demonstrates that DMDD is also a disorder with high morbidity. A limitation of this study is our lack of ability to further evaluate or comment on whether children in this study met criteria for DMDD and how that may have affected our results.

Despite these limitations, our systematic review of the extant literature and meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that subthreshold pediatric BP disorder is an identifiable morbid condition associated with significant functional impairment including psychiatric comorbidities and high rates of suicidality. Given the morbidity associated with this condition, further research is needed to more fully understand the course and outcomes of this population, the rate of conversion to the full syndrome as well as the investigation of treatment options most appropriate for these patients. This knowledge could lead to intervention efforts that not only could mitigate the distress and disability that poses to affected children but also mitigate the adverse outcomes associated with pediatric BP disorder.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Vaudreuil is currently receiving research support from AACAP, Harvard University and the Gerstner Family Foundation.

Dr. Faraone is supported by the K.G. Jebsen Centre for Research on Neuropsychiatric Disorders, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602805, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 667302 and NIMH grants 5R01MH101519 and U01 MH109536–01.

Dr. Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: AACAP, The Department of Defense, Food & Drug Administration, Headspace, Lundbeck, Neurocentria Inc., NIDA, PamLab, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sunovion, and NIH.

Sources of Financial and Material Support: This study was sponsored by the MGH Pediatric Psychopharmacology Council Fund (Boston, MA). The sponsors had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

In the past year, Dr. Faraone received income, potential income, travel expenses continuing education support and/or research support from Lundbeck, KenPharm, Rhodes, Arbor, Ironshore, Shire, Akili Interactive Labs, CogCubed, Alcobra, VAYA, Sunovion, Genomind and NeuroLifeSciences. With his institution, he has US patent US20130217707 A1 for the use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD.

Since January 2015, Dr. Janet Wozniak received no outside research support. She is author of the book, “Is Your Child Bipolar” published May 2008, Bantam Books. In 2015–2017, her spouse, Dr. John Winkelman, received an honorarium from Otsuka; royalties from Cambridge University Press and UptoDate; consultation fees from Advance Medical, FlexPharma and Merck; and research support from UCB Pharma, NeuroMetrix, and Luitpold.

Dr. Biederman has a financial interest in Avekshan LLC, a company that develops treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). His interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. Dr. Biederman’s program has received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Ingenix, Prophase, Shire, Bracket Global, Sunovion, and Theravance; these royalties were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH. In 2017, Dr. Biederman is a consultant for Aevi Genomics, Akili, Guidepoint, Medgenics, and Piper Jaffray. He is on the scientific advisory board for Alcobra and Shire. He received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. Through MGH corporate licensing, he has a US Patent (#14/027,676) for a non-stimulant treatment for ADHD, and a patent pending (#61/233,686) on a method to prevent stimulant abuse.

Dr. Vaudreuil, Maura DiSalvo, Rebecca Wolenski, and Nicholas Carrellas do not have any conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Rai D, Skapinakis P, Wiles N, Lewis G, Araya R. Common mental disorders, subthreshold symptoms and disability: longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010. November;197(5):411–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benvenuti A, Miniati M, Callari A, Giorgi Mariani M, Mauri M, Dell’Osso L. Mood Spectrum Model: Evidence reconsidered in the light of DSM-5. World J Psychiatry. 2015. March 22;5(1):126–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stata Corporation. Stata User’s Guide: Release 9. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demeter CA, Youngstrom EA, Carlson GA, et al. Age differences in the phenomenology of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013. May;147(1–3):295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafeman D, Axelson D, Demeter C, et al. Phenomenology of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified in youth: a comparison of clinical characteristics across the spectrum of manic symptoms. Bipolar Disord. 2013. May;15(3):240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paaren A, von Knorring AL, Olsson G, von Knorring L, Bohman H, Jonsson U. Hypomania spectrum disorders from adolescence to adulthood: a 15-year follow-up of a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2013. February 20;145(2):190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Buckley ME, Klein D. Bipolar disorder in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2002. July;11(3):461–475, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, McNamara NK, et al. Early symptoms of mania and the role of parental risk. Bipolar Disord. 2005. December;7(6):623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006. October;63(10):1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein B, et al. Four-year longitudinal course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009. July;166(7):795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stringaris A, Santosh P, Leibenluft E, Goodman R. Youth meeting symptom and impairment criteria for mania-like episodes lasting less than four days: an epidemiological enquiry. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010. January;51(1):31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmermann P, Bruckl T, Nocon A, et al. Heterogeneity of DSM-IV major depressive disorder as a consequence of subthreshold bipolarity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009. December;66(12):1341–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker G Predicting onset of bipolar disorder from subsyndromal symptoms: a signal question? Br J Psychiatry. 2010. February;196(2):87–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safer DJ, Rajakannan T, Burcu M, Zito JM. Trends in subthreshold psychiatric diagnoses for youth in community treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015. January;72(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts RE, Fisher PW, Turner JB, Tang M. Estimating the burden of psychiatric disorders in adolescence: the impact of subthreshold disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015. March;50(3):397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewinsohn PM, Shankman SA, Gau JM, Klein DN. The prevalence and co-morbidity of subthreshold psychiatric conditions. Psychol Med. 2004. May;34(4):613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, et al. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009. April;48(4):386–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Carlson GA, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force report on pediatric bipolar disorder: Knowledge to date and directions for future research. Bipolar Disord. 2017. September 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, et al. Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011. October;50(10):1001–1016 e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biederman J, Wozniak J, Tarko L, et al. Re-examining the risk for switch from unipolar to bipolar major depressive disorder in youth with ADHD: A long term prospective longitudinal controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2014. January;152-154:347–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wozniak J, Uchida M, Faraone SV, et al. Similar familial underpinnings for full and subsyndromal pediatric bipolar disorder: A familial risk analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2017. May;19(3):168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He J, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Bipolar Spectrum Disorder in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011. March;68(3):241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Crescenzo F, Serra G, Maisto F, et al. Suicide Attempts in Juvenile Bipolar Versus Major Depressive Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAACAP. 2017. October;56(10):825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merikangas KR, Cui L, Kattan G, et al. Mania With and Without Depression in a Community Sample of US Adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012. September;69(9): 943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blader JC, Carlson GA. Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among u.s. Child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004. Biol Psychiatry. 2007. July 15;62(2):107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Axelson D, Findling RL, Fristad MA, et al. Examining the proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis in children in the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012. October;73(10):1342–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell RH, Timmins V, Collins J, Scavone A, Iskric A, Goldstein BI. Prevalence and Correlates of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder Among Adolescents with Bipolar Disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016. March;26(2):147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margulies DM, Weintraub S, Basile J, Grover PJ, Carlson GA. Will disruptive mood dysregulation disorder reduce false diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children? Bipolar Disord. 2012. August;14(5):488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Althoff RR, Crehan ET, He JP, Burstein M, Hudziak JJ, Merikangas KR. Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder at Ages 13–18: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016. March;26(2):107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]